Abstract

Background

The diversity of symptoms associated with Parkinson’s and their impact on functioning have led to an increased interest in exploring factors that impact Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL). Although the experience of Parkinson’s is unique, some symptoms have a greater impact than others, e.g. depression. Moreover, as the risk of Parkinson’s increases with age, the financial and public health impact of this condition is likely to increase, particularly within the context of a globally ageing population. In Ireland, research is ongoing in the pursuit of causes and effective treatments for Parkinson’s; however, its impact on everyday living, functioning, and HRQoL is largely under-examined. This study aims to describe factors that influence HRQoL for people with Parkinson’s (PwP) in one region of Ireland.

Methods

A cross-sectional postal survey was conducted among people living with Parkinson’s (n = 208) in one area of Ireland. This survey included socio-demographic questions, Nonmotor Symptoms Questionnaire for Parkinson’s disease (NMSQuest), the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15), and the Parkinson’s disease Questionnaire (PDQ-39). Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS, IBM version 25 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, II, USA).

Results

Participants reflected a predominantly older population who were married, and lived in their own homes (91%). Participants diagnosed the longest reported poorer HRQoL regarding mobility, activities of daily living, emotional well-being, social support, cognition, communication domains and overall HRQoL. Lower HRQoL correlated with higher depression scores p < 0.001 and participants in the lower HRQoL cohort experienced 2.25 times more non-motor symptoms (NMSs) than participants with higher HRQoL. Hierarchical multiple linear regression analysis predicted Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS15) score, NMS burden, and years since diagnosis to negatively impact HRQoL. Principal component analysis (PCA) also indicated that for the population in this study, components measuring 1) independence/dependence 2) stigma 3) emotional well-being, and 4) pain were central to explaining core aspects of participants’ HRQoL.

Conclusions

Findings highlighted the negative impact of longer disease duration, NMS burden, depression, mobility impairments, and perceived dependence on HRQoL for PwP. The positive influence of perceived independence, social engagement along with close supportive relationships were also identified as key components determining HRQoL. Findings emphasised the importance of long-term healthcare commitment to sustaining social and community supports and therapeutic, rehabilitative initiatives to augment HRQoL for PwP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Parkinsonism is a complex range of symptoms used to describe the motor features of resting tremor, bradykinesia, and muscular rigidity [1, 2]. The incidence of Parkinson’s is approximately 1.5 times higher in men compared with women [3], with delayed onset in women credited to the neuroprotective effects of oestrogen on the nigrostriatal dopaminergic system [2]. Parkinson’s is the second most common multifactorial neurodegenerative disorder after dementia [3], with an estimated 6.1 million people worldwide living with Parkinson’s [4]. In Ireland, the incidence is 1–2:1000 in the general population and 1:100 in those over 80. With a population of 4,761,865 [5] there is an estimated 12,000 people living with Parkinson’s in Ireland [6].

Idiopathic or classic Parkinson’s is the most common form of Parkinsonism, which is a slowly progressive neurodegenerative condition [7]. Parkinson’s pathology includes not only dopaminergic cells but also cholinergic, noradrenergic, serotonergic, histaminergic, and glutaminergic cells, explaining the wide clinical spectrum of features associated with the condition [8]. Consequently, Parkinson’s can result in progressive disability characterised by motor and nonmotor features [2] that have a significant impact on health [9]. Motor symptoms include shuffling gait and gait fenestration [1], facial masking, [10, 11], poor balance, and stooped posture [12]. Furthermore, difficulty standing and turning, freezing (brief inability to move) [13], ‘off periods’ [14] and speech that is low, slow, or difficult to understand [15] along with small handwriting are additional motor symptoms [1]. The clinical spectrum of Parkinson’s is much broader than a classical movement disorder. It encompasses many non-motor impairments like depression symptomology, anxiety, sleep disturbances, dementia, pain, constipation, swallowing ability (caused by sensory and saliva deficits), sexual, and urinary dysfunction [16, 17]. These non-motor symptoms are extremely prevalent and often present before the onset of motor symptoms [18].

Ageing remains one of the most significant risk factors for developing Parkinson’s [19]. As more people are living into old age, the overall number of people living with Parkinson’s is also set to rise. European estimates have predicted that Parkinson’s will double by 2030, primarily due to ageing populations [4, 20]. Living longer poses challenges for planning and provision of health services [21] that can respond to the needs of individuals living with chronic conditions, including those with, declining health, increasing healthcare requirements, loss of independence, and social isolation. Consequently, nurses and other healthcare professionals need to accommodate age-related changes, comorbidities, effects of long-term medication, possible cognitive decline, the impact of depression, anxiety, and caregiver support when leading and managing care for PwP [22]. Given that the complex interplay of factors influencing HRQoL in Parkinson’s predominantly occurs within the context of advancing age, it also strengthens the importance of planning for and delivering multifaceted interdisciplinary care to meet these individuals’ healthcare needs.

The concept of HRQoL normally indicates not only the influence of disease and treatment on disability and daily functioning but also the influence of perceived health on an individual’s capability to live a satisfying life [23, 24]. It is suggested that HRQoL is a broad, multidimensional concept that includes symptoms of disease or a health condition, treatment side effects, and functional status across physical, social, and mental health life domains [25]. Critical aspects of HRQoL include physical and sensory functioning, agility, cognition, pain, emotional and psychological well-being i.e., “all within the skin”, making it a multifaceted dynamic concept [26]. Evaluation of HRQoL helps us to understand a person’s condition, identify the main issues affecting HRQoL deterioration, and determine individual needs and priorities [23] to guide healthcare management decisions. Research findings have shown the impact of symptoms and predictors of HRQoL for PwP [27, 28]. For example, the specific impact of motor [1] and NMSs including anxiety and depression [29, 30], excessive daytime sleepiness [31], stigma [32] and multidisciplinary care [33] have been reported. From a nursing perspective, understanding the wide-ranging factors influencing HRQoL can focus assessments and support interventions to reduce the negative health-related impact of this chronic debilitating condition [34].

Methods

Aim and objectives

The aim of this study was to explore HRQoL for people living with Parkinson’s. This understanding is important to inform health policy, practice, education, and research so healthcare professionals in Ireland and internationally can respond effectively using person-centred approaches to support and care for PwP. The study objectives were to; i) describe demographic characteristics ii) describe types, and frequencies of NMSs, iii) investigate reported depression symptomology, iv) examine baseline HRQoL data (PDQ-39 scale), v) explore associations between socio-demographic variables, NMSs, depression symptomology, and perceived HRQoL, and vi) examine factors influencing HRQoL scores.

Design

This research was part of a larger mixed methods study exploring QoL and living with Parkinson’s. A cross-sectional postal survey design using a self-reporting 91-item questionnaire across four scales was used in this study. Scale one, demographics, included 7 items consisting of gender, age, marital status, time since diagnosis, living arrangements e.g., where participants lived, whom participants lived with, and their sources of support. Scale two, the NMSQuest, consisted of 30 items focusing on participants’ accounts of NMSs with yes/no responses to each question [35, 36]. Scale three, GDS-15 [37], was used to draw attention to the presence of depression symptomology in the previous week, and responses required a yes/no answer [38]. Cut-off scores used in this study reflected suggestions of 0–4 as normal or no clinical concern, 5–8 mild depression symptomology, 9–11 moderate, and 12–15 severe depression symptomology [37]. Total scores were also recorded. Scale four, the PDQ-39, was included as a disease-specific, self-reporting HRQoL questionnaire, designed to assess aspects of functioning and well-being adversely affected by Parkinson’s [39]. The PDQ-39 is composed of 39 items across eight subscales/domains, including mobility, activities of daily living, emotional well-being, stigma, social support, cognition, communication, and bodily discomfort [39], and the instrument has tested strongly psychometrically [40]. The PDQ-39 Summary Index score (PDQ-39 SI) reflected the sum of dimension total scores divided by 8 [39]. The University Hospital Limerick Research Ethics Committee provided approval to undertake the survey. Informed consent was obtained; participants were informed of the study purpose, what participation would involve, the voluntary nature of participation, risks, benefits, confidentiality and links to further supports if needed.

Participants and setting

A purposive sample of the total population of people diagnosed with idiopathic Parkinson’s (n = 358) accessing neurological services at a University teaching hospital in one region of Ireland were invited to participate in this study. A response rate of 58.1% (n = 208) was achieved. Reasons for non-response included personal choice, health reasons, item nonresponse, or partial nonresponse (missing data). Data were collected within a PhD study completed in 2020.

Statistical methods

Data were analysed using data analysis software, Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), IBM version 25 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, II, USA). Demographics and NMSs: Descriptive analyses [41] including frequencies and mean rankings summarised participant characteristics and NMS data. GDS-15: descriptive analyses assessed scores and categories of depression symptomology. PDQ-39: Descriptive analyses initially calculated the mean, median, SD, frequencies, range, and centile scores from each of the eight PDQ-39 dimensions and the PDQ-39 SI scores. Predominance of categorical and ordinal variables and violation of the assumption of normality evidenced by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov statistics [42] supported application of a range of non-parametric statistical tests (Additional file 1). The Mann-Whitney U was employed to test for differences between PDQ-39 SI scores and gender. The Kruskal-Wallis test analysed for differences between PDQ-39 SI scores, and age, years since diagnosis, NMS burden, and GDS-15 scores across three HRQoL cohorts (high, average, low). The relationships between number of NMSs (NMS burden) and PDQ-39 SI scores were investigated using Spearman’s rho test [42]. Odds ratios [43] analysed the proportion of respondents in each HRQoL cohort (high, average, low) likely to experience each of the 30 NMSs. Hierarchical multiple linear regression analysis determined the extent to which explanatory variables were linearly related to the PDQ-39 SI score. Finally, PCA was undertaken to produce linear combinations of PDQ-39 variables that explained most variability in correlation patterns [42].

Results

Participant characteristics

Three hundred and fifty-eight PwP were invited and 208 returned surveys (response rate of 58.1%). Of the respondents, 61.5% (n = 128) were men and 38.5% (n = 80) were women, 89.9% (n = 187) were over 60 years and 95.2% (n = 197) were diagnosed 2 years or longer. Over 72% (n = 150) were married, 70.7% (n = 147) lived with their spouse/partner and 90.9% (n = 189) lived in their own home. Mean rankings indicated husband, wife, or partner as the most important source of support (mean rank 3.34) (Table 1, Table 2).

Types of NMSs

The top five NMSs identified were: a sense of urinary urgency 68.8% (n = 139), getting up regularly at night to pass urine 59.4% (n = 117), problems remembering or forgetting 58.3% (n = 119), unpleasant leg sensations 57.6% (n = 114) and constipation 51.3% (n = 102) (Fig. 1).

Depression symptomology

GDS-15 results identified that 51.1% (n = 97) of respondents recorded normal scores or did not report symptomology of depression, 30% (n = 57) of participant scores indicated mild depression, 10.5% (n = 20) moderate depression, and 8.4% (n = 16) reported scores indicating severe depression. Of note, while 81.1% (n = 154) of respondents reported symptoms of either no or mild depression, the combined frequencies for moderate and severe depression symptomology was 18.9% (n = 36).

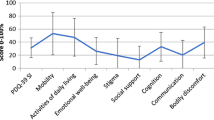

HRQoL descriptives

The scores from each of the eight PDQ-39 dimensions along with the PDQ-39 SI score are presented in Additional file 2. In this study, the influence of movement and mobility alterations were reflected in the PDQ-39 survey data, where several respondents reported having trouble looking after their home (39.2%, n = 78) or getting around their house (27.7%, n = 56). Changes to movement, mobility, and bodily functioning also spanned beyond the home to community with some respondents reporting difficulty walking short distances (100 yards). There were 173 (83.2%) completed participant PDQ-39 SI scores that ranged from 0 to 72.76. The mean score was 30.34, median was 28.02, and standard deviation was 17.2. Higher PDQ-39 SI scores represented lower HRQoL and lower PDQ-39 SI scores represented higher HRQoL (Additional file 2).

HRQoL and age

A Kruskal-Wallis test revealed a statistically significant difference in PDQ-39, dimension 1 ‘Mobility’ scores across age groups, (Gp 1, n = 0: 20 years or under, Gp 2, n = 0: 21–30 years, Gp 3 n = 1: 31–40 years, Gp 4 n = 0: 41–50 years; Gp 5, n = 17: 51–60 years, Gp 6, n = 57: 61–70 years, Gp 7, n = 86: 71–80 years, Gp 8, n = 26: 81 or older), X2 (4, n = 187) =12.4, p = 0.15, indicating that participants 81 years and older recorded a higher median score (Md = 60) than other age categories. Median values ranged from 2.5–47.5 suggesting that people in the oldest age category (81 years and older) had lower HRQoL in the mobility subscale of the PDQ-39 scale.

HRQoL and years since diagnosis

Survey participants diagnosed the longest (22 years or more) scored poorer HRQoL in mobility p < 0.001, activities of daily living p < 0.001, social support p < 0.019, communication p < 0.001, and the overall PDQ-39 SI scores p < 0.001 than other years since diagnosis cohorts. Respondents diagnosed 7–11 years scored poorer HRQoL for emotional well-being than other years since diagnosis cohorts (p = 0.004), and participants diagnosed 12–16 years, and 22 years, reported poorer HRQoL with cognition (p = 0.008).

HRQoL and NMS burden

The relationship between the PDQ-39 SI score and NMS burden was investigated using Spearman’s rho test. There was a strong positive correlation between the two variables, r = .660, n = 173, p < 0.001, with high levels of NMS burden associated with higher PDQ-39 SI scores meaning the higher the number of NMSs the lower the HRQoL.

Three even cohorts were created from the available 173 PDQ-39 SI scores. The first group represented people with higher HRQoL with PDQ-39 SI scores ranging from 0 to 19.69. The second cohort represented people with average HRQoL with scores ranging from 19.84–37.4. The third cohort included participants with lower HRQoL and scores ranging from 38.86–72.76. A Kruskal-Wallis test revealed a statistically significant difference in NMS burden scores across three HRQoL cohorts (high, average, low HRQoL), (Gp 1, n = 57: high HRQoL, Gp2, n = 56: average HRQoL, Gp3, n = 60: low HRQoL), X2 (2, n = 173) = 55.66, p < 0.001. The low HRQoL group recorded a higher median score (Md = 121.6) than the other two HRQoL cohorts (average HRQoL, Md = 85) and (high HRQoL, Md = 52.7) respectively, signalling that respondents in the low HRQoL cohort reported a higher NMS burden.

Respondents in the high HRQoL cohort reported experiencing 391 NMSs in the previous month. Those in the average HRQoL cohort reported experiencing 591 NMSs and those in the low HRQoL cohort reported 880 symptoms in the previous month. The NMS burden was 1.51 times higher for people in the average HRQoL cohort (average PDQ-39 SI scores) compared with those in the high HRQoL cohort (low PDQ-39 SI HRQoL scores). The NMS burden was 1.49 times higher for people in the low HRQoL cohort (low PDQ-39 SI scores) compared with those in the average HRQoL cohort (average PDQ-39 SI scores). Overall respondents in the low HRQoL cohort (high PDQ-39 SI scores) experienced 2.25 times more NMSs than respondents with high HRQoL.

HRQoL cohorts and NMSs

The odds ratios [41] for experiencing individual NMSs were calculated through examining the proportion of respondents in each HRQoL cohort, (high, average, and low HRQoL) likely to experience each of the 30 NMSs. As odds ratios can only be undertaken in a 2 by 2 table, three binary variables were used 1) ‘high’ HRQoL and ‘not high’ HRQoL 2) ‘average’ HRQoL and ‘not average’ HRQoL and 3) ‘low’ HRQoL and ‘not low’ HRQoL. The odds of NMSs such as difficulty concentrating (OR 7.77), incomplete bowel emptying (OR 6.49), feeling anxious (OR 5.78), seeing or hearing things that others say are not true (OR 5.73) were more likely to be experienced by participants with lower HRQoL (than participants in high and average HRQoL cohorts) (Fig. 2).

HRQoL cohorts and depression symptomology

A Kruskal-Wallis test revealed a statistically significant difference in GDS-15 scores across the three HRQoL cohorts (high, average, low HRQoL), Gp 1, n = 52: high HRQoL, Gp2, n = 50: average HRQoL, Gp3, n = 55: low HRQoL), X2 (2, n = 157) = 60.13, p < 0.001. The low HRQoL group recorded a higher median score (Md = 7) than the other two HRQoL cohorts which recorded medians of 4 (average HRQoL) and 1 (high HRQoL). These results indicate that respondents in the lower HRQoL cohort reported higher GDS-15 scoring for depression symptomology. The relationship between overall HRQoL scores (PDQ-39 SI scores) and depression symptomology scores (GDS-15) utilising Spearman’s rho identified a strong positive correlation between the two variables rho = 0.609, n = 177, p < 0.001, with high PDQ-39 SI scores associated with high depression scores (higher PDQ-39 SI scores indicate poorer HRQoL) (Fig. 3).

Assessing predictors of HRQoL

Hierarchical multiple regression was used to assess the ability of four control measures (gender, where participants usually lived, who they usually lived with, and marital status) to predict overall HRQoL (as measured by the PDQ-39 SI score), after controlling for the influence of the GDS-15 score, NMS burden, years since diagnosis and age. Preliminary analyses ensured no violation of the assumptions of normality, linearity, multicollinearity, and homoscedasticity. GDS-15 score, NMS burden, years since diagnosis, and age were entered at step 1 explaining 53.9% of the variance in HRQoL, F (4, 152) = 44.37, p < 0.001.

After entry of the variables where participants usually lived, who they usually lived with, marital status, and gender at step 2, the total variance explained by the model was 56.9%, R2 change = .030, F (8, 148) = 24.43, F change = 2.61, p = .038. Hence, the second block of control measures only explained a further 3% of the variance in HRQoL after controlling for GDS-15 score, NMS burden, years since diagnosis and age. These results supported model 1 as the model that most accurately explained the effects of key variables including demographics, NMSs and reported depression symptomology on participants’ HRQoL.

Model 1 with four variables GDS-15 score, NMS burden, years since diagnosis, and age were predicted to negatively influence HRQoL. Three of the four control variables were statistically significant. The NMS burden measure recorded the highest beta value (beta = 0.415, p < 0.001) followed by the GDS-15 measure (beta = 0.374 p < 0.001). The lowest significant beta measure was years since diagnosis (beta −.151 p = 0.008). These results strengthen understanding around the impact of depression symptomology, the number of NMSs experienced and length of time diagnosed, in predicting HRQoL for individuals living with Parkinson’s (Additional File 3).

Underlying components of HRQoL

The 39 items of the PDQ-39 underwent PCA to investigate underlying components of the data. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy was 0.91, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (p < 0.001) confirming that the observed correlation matrix was appropriate for PCA. Initial analysis revealed the presence of seven components with eigenvalues exceeding 1, explaining 65.5% of total variance. Examination of the rotated component matrix indicated the removal of eight questions from the analysis that had patterns of low coefficient loadings < 0.6.

Analysis was rerun with six components explaining 67.9% variance; four factors accounted for 60.2% of this and the screeplot revealed a clear break after four components. Results from parallel analysis also showed four components with eigenvalues exceeding the corresponding criterion values for a randomly generated data matrix of the same size (39 variables X 208 participants). Hence, a four-component solution was forced. To aid interpretation of these four components oblique rotation (varimax) was performed. The rotated solution showed loadings on four components accounting for 60.2% variance, component 1 accounted for 40.2%, component 2 a further 8.49%, component 3, 6.13%, and component 4, 5.37% variance. This analysis strengthens recognition of the multidimensional influences on HRQoL for PwP including perceptions of independence/dependence, stigma stemming from interactions with others, emotional well-being, and NMSs such as pain (Table 3).

Discussion

Respondents included a predominantly older population who were married, lived with their spouse/partner in their own home, and had been diagnosed with Parkinson’s for two years or longer. Consistent with international literature, there were more men than women in the sample [44]. Interestingly, a large proportion of survey respondents in this study reported never having problems with close personal relationships or lacking support from family or close friends. Indeed, a profile of people living with Parkinson’s for over 20 years showed that the majority lived at home with a family caregiver [45]. Elsewhere, “social relationships” (with family, friends, and neighbours) were revealed as most significant for PwP [46]. Karlstedt et al. [47] found that although PwP may deteriorate over time, high relationship quality can produce gratification, meaning, and support, enhance negative consequences, and improve HRQoL. This emphasises the importance of establishing a profile of available supports, to guide and facilitate pathways for individualised person-centred care [48], that can support the HRQoL of PwP. Hence, interventions embracing social support, respite care, couple therapy, or counselling may help caregivers and individuals adapt and adjust to ever-changing care situations and find inward strength to cope [47].

In this study, presence, type, and disruptions caused by NMSs, often referred to as invisible symptoms, manifested their influence on HRQoL. Concurring reports have suggested that NMSs influence long-term HRQoL for PwP [49]. Moreover, findings show how they may influence HRQoL more than motor symptoms [40], and psychological well-being [50] thereby highlighting the impact of NMSs and their relationship to HRQoL.

Within this study, respondents living with Parkinson’s for longer timeframes, recorded a higher NMS burden, a finding supported by Sanchez-Martinez et al. [17]. There was also a greater than two-fold increase in the NMS burden for those in the low HRQoL cohort compared with participants in the high HRQoL cohort. Results indicated that the odds of experiencing individual NMSs were more likely in participants with lower HRQoL. Indeed, NMS burden can negatively affect HRQoL [51]. Furthermore, people with more severe NMSs have reported more unmet needs such as accessibility to healthcare professionals [22]. Given that respondents were community-dwelling, this highlights the vital role of primary and community nurses in providing impeccable assessment and therapeutic care that alleviates the impact of NMSs on PwP [22].

As detailed in the results, most survey respondents reported either no depression or mild depression; nonetheless, combined frequencies for moderate and severe depression symptomology were clinically significant. This supports earlier findings [52, 53] signalling the prevalence of major depressive disorders in PwP. Principal component and regression analyses established depression score as a significant contributor to, and determinant of HRQoL, which is comparable with previous research results that highlighted depression as one of the most important determinants of poor HRQoL for PwP [27, 54].

Of interest within this study was the finding which revealed a statistically significant difference in HRQoL scores (high, average, low HRQoL cohorts) across GDS-15 depression symptomology categories. Respondents in the low HRQoL cohort recorded more severe depression symptomology. From a health-professional perspective, two simple questions are recommended to assist identification of depression symptomology in the previous month, ‘have you often been bothered by feeling down, depressed or hopeless’? and, ‘Have you often been bothered by having little interest or pleasure in doing things’? [55] Undoubtedly, being vigilant to depression symptomology, employing listening skills, along with ascertaining a comprehensive history are fundamental nursing skills. Furthermore, referral to healthcare practitioners competent to undertake more in-depth physical and mental health assessments using validated instruments (e.g., GDS-15 or the combined Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale HADS) is advised to indicate presence and severity of psychological difficulties, identify individual preferences, along with family, and social support needs [56, 57]. This is particularly important given the negative impact of depression and anxiety on the lives of PwP [58].

Findings from this study also emphasised the everyday impact of Parkinson’s on ambulation, where almost half (48.5%) of respondents reported difficulty walking ½ mile. Findings from the wider literature highlight that exercise may help motor and NMSs and prevent secondary complications of immobility (cardiovascular, osteoporosis) [59]. Additionally, exercise can help optimise function and performance of life activities [60]. Developing exercise and walking capacity, balance, muscle power, and compensatory methods to alleviate pain during ambulation could also reduce the work of walking from a rehabilitation perspective [61]. Through rehabilitation, growth in knowledge and skills can increase personal control, self-management, role participation, and satisfaction [62]. This stresses the importance of resource planning and long-term healthcare professional commitment to sustaining rehabilitative therapy initiatives for PwP that truly foster independence and augment HRQoL.

However, in this study, the influence of Parkinson’s on mobility went beyond mere estimates of walking distance; many participants indicated they would need someone to accompany them in public. Furthermore, almost a third of survey participants reported that they felt frightened (often or always) about falling over in public. Horning et al. [63] reported gait deterioration, falls, and functional decline as key symptoms challenging home safety. These cause noticeable restrictions in a range of activities, disability, and altered autonomy [64] and highlight the interwoven nature of mobility, fear, and dependence. Falls are significantly related to reduced HRQoL [34, 65]. More recently, it was reported that ‘locomotion dysfunction’ (gait and balance difficulties) scored highest in motor characteristics underscoring the importance of gait deficits to HRQoL [28]. One common dysfunction, freezing of gait, is a complex motor fluctuation connected with advancing Parkinson’s [66]. As motor fluctuations also have direct and indirect effects on HRQoL (directly affecting pain and fatigue, and indirectly mood and sleep), assessing and managing these effectively could improve overall HRQoL [67]. Recommendations from this study include the need to supplement HRQoL research instruments such as the PDQ-39 by including additional instruments to capture the everyday impact of Parkinson’s such as freezing of gait (e.g. The Freezing of Gait Questionnaire FoGQ), and other influences such as falls incidence and fear of falling (FoF) e.g. Fall Efficacy Scale-International (FES-I).

Principal component analysis in this study (PDQ-39 scale) revealed one of the four components determining HRQoL was independence/dependence. Previously, perceived autonomy was reported to affect HRQoL [68]. Being dependent on others causes feelings of insecurity and reduces confidence in self-image and identity [69]. The idea that Parkinson’s impacts meaningful activities was previously linked to losses associated with previous social identities such as gardener, cook, mother/father, or being able to wear heeled shoes [70]. Without sufficient personal control, people also find adaptation problematic [71]. Subsequently, they may experience increased effects of chronic illness and its treatment, resulting in even lower HRQoL. Findings from Gusdal et al.’s [72] delphi study described having a social life, feeling safe and being able to retain one’s control as requirements for healthy and independent living among older people generally. Social care is valued for allowing choice, control, and enabling people to maintain independence [73]. Hence, more creative community supports, based on individual needs in line with an active ageing concept [74], are required to facilitate social and advocacy needs around independence to sustain and improve HRQoL. This is further strengthened by aspirations to support people to live independently in the community for as long as possible, and to co-design population service requirements [21]. Udo’s (2016) [75] analysis of active ageing also incorporates continued participation in life and health to enable individuals to enjoy a positive QoL, as they grow older. Hence, promotion of independence and participation must be primary considerations for healthcare policy development and service delivery to preserve HRQoL for PwP.

Survey findings indicated over a third of respondents had difficulty getting around in public, and/or needed someone to accompany them. Over half the respondents indicated a preference for staying at home rather than socialising. In addition, poorer HRQoL in the domain of social support was evidenced by respondents with longstanding Parkinson’s. Social isolation independently influences the prospect of depression or anxiety, with loneliness being a cyclical risk factor for declining social life [76]. All these situations ultimately reduce social roles, well-being, and HRQoL.

While the largely inevitable physical consequences of disease take hold, social withdrawal and isolation should not be viewed as inevitable nor intractable [76]. From a health and social perspective, activities that engage PwP where they feel valued, and part of communities is essential. This is especially important for individuals diagnosed for longer periods, where social isolation may creep in. This again emphasises the importance of addressing loneliness and social network size to improve mental health of older PwP [76]. It is vital that barriers to participation are removed for older people generally and more opportunities emerge for continued involvement in cultural, economic, and social dimensions of life, according to needs, preferences, and capabilities [21]. From a HRQoL perspective, healthcare professionals should be mindful of the positive influence of feeling part of a community of people, be that a committee or a group.

Limitations and recommendations

This research was conducted in one area of Ireland, therefore participants’ responses may not be generalisable to the whole population of people living with Parkinson’s. The survey reflected self-reports at a single point in time with no follow-up survey. The stage of Parkinson’s was not clinically assessed during the research, hence, progression patterns and severity could not be objectively assessed and subsequently related to key research variables and subjective reports of HRQoL. Missing data was omitted from the analysis.

The NMS Quest, and GDS-15 described presence of symptoms and the PDQ-39 assessed aspects of functioning and well-being adversely affected by Parkinson’s. However, these instruments did not examine participants’ experiences and feelings around NMSs, depression and HRQoL. This calls for more in-depth qualitative exploration to expand breadth and range of inquiry and provide fuller and deeper understandings on the impact of Parkinson’s on participants’ lives.

Focused multidisciplinary rehabilitative programmes targeting walking ability, balance, FoG, falls and FoF should be available in primary care to prevent and address sedentary lifestyle, and falls. It is also recommended that the PDQ-39 as a Parkinson’s specific HRQoL instrument is revised to capture the everyday impact of Parkinson’s on individuals’ lives such as FoG, falls, and FoF. Future research should consider sampling and recruitment within the context of gender representation to identify if gender sensitive healthcare interventions may be effective in ameliorating the impact of NMSs on perceived HRQoL. Healthcare policy needs to keep promotion of independence as a central consideration when resourcing service delivery for PwP. This is important to support people to live independently in their own community for as long as possible.

Conclusions

This study aimed to explore factors that influence HRQoL for PwP. From a broader perspective, the findings allude to the positive benefits of close relationships in providing a supportive context moderating the psychological well-being of participants, particularly within the context of living in one’s own home. Overall, findings indicated the differing impact of NMSs on HRQoL of men and women, those with longer disease duration, and people with poorer self-reported HRQoL. The impact of depression was identified, stressing the need for vigilance, comprehensive assessment, and referral for individualised follow-up care. This is important given the evidence illuminating the powerful influence of depression on overall QoL in Parkinson’s. The influence of movement and mobility alterations were reflected in the PDQ-39 survey data, which also revealed Independence/dependence and social engagement as key components determining HRQoL for PwP.

These findings strengthen recognition of HRQoL determinants as more than just physical but as also encapsulating a sense of self, emotional well-being, feelings of control, and social engagement. Statistical analysis in this study’s population also uniquely established a framework of regression that reinforces understanding around the impact of depression symptomology, NMSs, and the length of time diagnosed in predicting HRQoL for PwP. These findings stress the importance of resource planning and long-term healthcare professional commitment to sustaining rehabilitative therapy initiatives for PwP that foster independence and augment HRQoL.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are not publicly available as participants have not given consent for public availability of their data. But it is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- FoF:

-

Fear of Falling

- FoG:

-

Freezing of Gait

- GDS-15:

-

Geriatric Depression Scale- 15 items

- HRQoL:

-

Health-Related Quality of Life

- NMSQuest:

-

Nonmotor Symptoms Questionnaire for Parkinson’s disease

- PDQ:

-

Parkinson’s disease Questionnaire

- PwP:

-

People with Parkinson’s

References

Moustafa A, Chakravarthy S, Phillips J, Gupta A, Keri S, Polner P, et al. Motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease: a unified framework. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;68:727–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.07.010.

DeMaagd G, Philip A. Parkinson’s disease and its management: part 1: disease entity, risk factors, pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and diagnosis. Pharm Ther. 2015;40(8):504 available: PMCID:PMC4517533.

Kaur R, Mehan S, Singh S. Understanding multifactorial architecture of Parkinson’s disease: Pathophysiology to management. Neurol Sci. 2019;40(1):13–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-018-3585-x.

Dorsey ER, Elbaz A, Nichols E, Abd-Allah F, Abdelalim A, Adsuar JC, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of Parkinson's disease, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(11):939–53. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.26744.

Central statistics Office (CSO). Census 2016, profile 3, an age profile of Ireland. Dublin: CSO; 2017. [cited June 2021]. Available from: https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-cp3oy/cp3/.

Parkinson’s Association of Ireland. What is Parkinson’s disease? 2020. [cited June 2021]. Available from https://www.parkinsons.ie/what-is-parkinsons-disease/.

Levin J, Kurz A, Arzberger T, Giese A, Höglinger GU. The differential diagnosis and treatment of atypical parkinsonism. Deutsches Ärzteblatt Int. 2016;113(5):61. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2016.0061.

Williams-Gray C, Worth P. Parkinson’s disease. Medicine. 2016;44(9):542–6.

Moreira RC, Zonta MB, Araújo AP, Israel VL, Teive HA. Quality of life in Parkinson’s disease patients: progression markers of mild to moderate stages. Arquivos de neuro-psiquiatria. 2017;75(8):497–502. https://doi.org/10.1590/0004-282X20170091.

Fereshtehnejad SM, Skogar Ö, Lökk J. Evolution of Orofacial symptoms and disease progression in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: longitudinal data from the Jönköping Parkinson registry. Parkinson’s Dis. 2017;16:2017. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/7802819.

Maffoni M, Giardini A, Pierobon A, Ferrazzoli D, Frazzitta G. Stigma experienced by Parkinson’s disease patients: a descriptive review of qualitative studies. Parkinson’s Dis. 2017;24:2017. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/7203259.

Anderson JM, Oakley PA, Harrison DE. Improving posture to reduce the symptoms of Parkinson’s: a CBP® case report with a 21-month follow-up. J Phys Ther Sci. 2019;31(2):153–8. https://doi.org/10.1589/jpts.31.153.

Sawada M, Wada-Isoe K, Hanajima R, Nakashima K. Clinical features of freezing of gait in Parkinson's disease patients. Brain Behav. 2019;9(4):e01244. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.1244.

Rastgardani T, Armstrong MJ, Gagliardi AR, Grabovsky A, Marras C. Experience and Impact of OFF Periods in Parkinson’s Disease: A Survey of Physicians, Patients, and Carepartners. J Parkinson's Dis. 2020;10(1):315–24. https://doi.org/10.3233/JPD-191785.

Brabenec L, Mekyska J, Galaz Z, Rektorova I. Speech disorders in Parkinson’s disease: early diagnostics and effects of medication and brain stimulation. J Neural Trans. 2017;124(3):303–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-017-1676-0.

Tibar H, El Bayad K, Bouhouche A, Ait Ben Haddou EH, Benomar A, Yahyaoui M, et al. Non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease and their impact on quality of life in a cohort of Moroccan patients. Front Neurol. 2018;9:170. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2018.00170.

Sánchez-Martínez CM, Choreño-Parra JA, Placencia-Álvarez N, Nuñez-Orozco L, Guadarrama-Ortiz P. Frequency and dynamics of non-motor symptoms presentation in Hispanic patients with Parkinson disease. Front Neurol. 2019;10:1197. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2019.01197.

Mantri S, Morley JF. Prodromal and early Parkinson’s disease diagnosis. Pract Neurol. 2018;35:28–31.

Hou Y, Dan X, Babbar M, Wei Y, Hasselbalch SG, Croteau DL, et al. Ageing as a risk factor for neurodegenerative disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2019;15(10):565–81. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-019-0244-7.

European Parkinson’s disease Association (EPDA). Move for change results. 2013. [Cited June 2021]. Available from: www.epda.eu.com/move-for-change.

Department of Health. Slaintecare actionplan 2019. Dublin: Department of Health; 2019. p. 57.

Lee J, Kim Y, Kim S, Kim Y, Lee YJ, Sohn YH. Unmet needs of people with Parkinson’s disease: A cross-sectional study. J Advanc Nurs. 2019a;75(12):3504–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14147.

Martinez-Martin P. What is quality of life and how do we measure it? Relevance to Parkinson's disease and movement disorders. Move Disord. 2017;32(3):382–92. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.26885.

Haraldstad K, Wahl A, Andenæs R, Andersen JR, Andersen MH, Beisland E, et al. A systematic review of quality of life research in medicine and health sciences. Qual Life Res. 2019;28(10):2641–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-019-02214-9.

Revicki DA, Kleinman L, Cella D. A history of health-related quality of life outcomes in psychiatry. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2014;16(2):127.

Sajid MS, Tonsi A, Baig MK. Health-related quality of life measurement. International journal of health care quality assurance; 2008. p. 365.

Kuhlman GD, Flanigan JL, Sperling SA, Barrett MJ. Predictors of health-related quality of life in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2019;65:86–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2019.05.009.

van Uem JM, Marinus J, Canning C, van Lummel R, Dodel R, Liepelt-Scarfone I, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with Parkinson's disease—a systematic review based on the ICF model. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;61:26–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.11.014.

Věchetová G, Slovák M, Kemlink D, Hanzlíková Z, Dušek P, Nikolai T, et al. The impact of non-motor symptoms on the health-related quality of life in patients with functional movement disorders. J Psychosom Res. 2018;115:32–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.10.001.

Su W, Liu H, Jiang Y, et al. Correlation between depression and quality of life in patients with Parkinson's disease. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2021;202:106523. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clineuro.2021.106523.

Yoo SW, Kim JS, Oh YS, Ryu DW, Lee KS. Excessive daytime sleepiness and its impact on quality of life in de novo Parkinson’s disease. Neurol Sci. 2019;40(6):1151–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-019-03785.

Ma HI, Saint-Hilaire M, Thomas CA, Tickle-Degnen L. Stigma as a key determinant of health-related quality of life in Parkinson’s disease. Qual Life Res. 2016;25(12):3037–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-016-1329-z.

Marumoto K, Yokoyama K, Inoue T, Yamamoto H, Kawami Y, Nakatani A, et al. Inpatient enhanced multidisciplinary care effects on the quality of life for Parkinson disease: a quasi-randomized controlled trial. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2019;32(4):186–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891988719841721.

Soh SE, McGinley JL, Watts JJ, Iansek R, Murphy AT, Menz HB, et al. Determinants of health-related quality of life in people with Parkinson’s disease: a path analysis. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(7):1543–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-012-0289-1.

Chaudhuri KR, Healy DG, Schapira AH. National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Non-motor symptoms of Parkinson's disease: diagnosis and management. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5(3):235–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70373-8 PMID: 16488379.

Chaudhuri KR, Martinez-Martin P, Brown RG, Sethi K, Stocchi F, Odin P, et al. The metric properties of a novel non-motor symptoms scale for Parkinson's disease: results from an international pilot study. Move Disord. 2007;22(13):1901–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.21596.

Greenberg SA. The geriatric depression scale (GDS). Best Pract Nurs Care Older Adults. 2012;4(1):1–2.

Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatric Res. 1982;17(1):37–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4.

Peto V, Jenkinson C, Fitzpatrick R, Greenhall R. The development and validation of a short measure of functioning and wellbeing for individuals with Parkinson's disease. Qual Life Res. 1995;4(3):241–8.

Martinez-Martin P, Jeukens-Visser M, Lyons KE, Rodriguez-Blazquez C, Selai C, Siderowf A, et al. Health-related quality-of-life scales in Parkinson's disease: Critique and recommendations. Move Disord. 2011;26(13):2371–80. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.23834.

Polit D, Beck C. Essentials of nursing research. Appraising evidence for nursing practice. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2018.

Pallant J. SPSS survival manual: a step-by-step guide to data analysis using IBM SPSS. 7th ed. London: Open University Press; 2020.

Andrade C. Understanding relative risk, odds ratio, and related terms: as simple as it can get. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(7):e857–61. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.15f10150 PMID: 26231012.

Cerri S, Mus L, Blandini F. Parkinson's Disease in Women and Men: What's the Difference? J Parkinsons Dis. 2019;9(3):501–15. https://doi.org/10.3233/JPD-191683 PMID: 31282427; PMCID: PMC6700650.

Hassan A, Wu SS, Schmidt P, Simuni T, Giladi N, Miyasaki JM, et al. The profile of long-term Parkinson’s disease survivors with 20 years of disease duration and beyond. J Parkinson's Dis. 2015;5(2):313–9. https://doi.org/10.3233/JPD-140515.

Takahashi K, Kamide N, Suzuki M, Fukuda M. Quality of life in people with Parkinson’s disease: the relevance of social relationships and communication. J Physi Ther Sci. 2016;28(2):541–6. https://doi.org/10.1589/jpts.28.541.

Karlstedt M, Fereshtehnejad SM, Aarsland D, Lökk J. Determinants of dyadic relationship and its psychosocial impact in patients with Parkinson’s disease and their spouses. Parkinson’s Dis. 2017:2017. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/4697052.

Pusswald G, Fleck M, Lehrner J, Haubenberger D, Weber G, Auff E. The “Sense of Coherence” and the coping capacity of patients with Parkinson disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24(12):1972. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610212001330.

Maeda T, Shimo Y, Chiu SW, Yamaguchi T, Kashihara K, Tsuboi Y, et al. Clinical manifestations of nonmotor symptoms in 1021 Japanese Parkinson's disease patients from 35 medical centers. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2017;38:54–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2017.02.024.

Nicoletti A, Mostile G, Stocchi F, Abbruzzese G, Ceravolo R, Cortelli P, et al. Factors influencing psychological well-being in patients with Parkinson’s disease. PLoS One. 2017;12(12):e0189682. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0189682.

Santos-García DS, de Deus FT, Castro ES, Borrue C, Mata M, Vila BS, et al. Non-motor symptoms burden, mood, and gait problems are the most significant factors contributing to a poor quality of life in non-demented Parkinson's disease patients: results from the COPPADIS study cohort. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2019;66:151–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2019.07.031.

Reijnders JS, Ehrt U, Weber WE, Aarsland D, Leentjens AF. A systematic review of prevalence studies of depression in Parkinson's disease. Move Disord. 2008;23(2):183–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.21803.

Vanderheyden JE, Gonce M, Bourgeois P, Cras P, De Nayer AR, Flamez A, et al. Epidemiology of major depression in Belgian parkinsonian patients. Acta Neurol Belg. 2010 Jun 1;110(2):148.

Chuquilín-Arista F, Álvarez-Avellón T, Menéndez-González M. Prevalence of depression and anxiety in Parkinson disease and impact on quality of life: a community-based study in Spain. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2020;33(4):207–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891988719874130.

National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Depression in adults, recognition and management, Clinical guideline CG90. 2009 [cited June 2021]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg90.

Goodarzi Z, Ismail Z. A practical approach to detection and treatment of depression in Parkinson disease and dementia. Neurol Clin Pract. 2017;7(2):128–40. https://doi.org/10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000351. Erratum in: Neurol Clin Pract. 2018 Aug; 8(4):278. PMID: 28409063; PMCID: PMC5386841.

National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Parkinson’s disease in adults, NICE guidelines, NG71. 2017. [cited June 2021]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng71.

Khedr EM, Abdelrahman AA, Elserogy Y, et al. Depression and anxiety among patients with Parkinson’s disease: frequency, risk factors, and impact on quality of life. Egypt J Neurol Psychiatry Neurosurg. 2020;56:116. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41983-020-00253-5.

van der Kolk NM, King LA. Effects of exercise on mobility in people with Parkinson's disease. Movement Disord. 2013;28(11):1587–96. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.25658.

Eriksson BM, Arne M, Ahlgren C. Keep moving to retain the healthy self: the meaning of physical exercise in individuals with Parkinson’s disease. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35(26):2237–44. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2013.775357.

Bouchard V, Duquette P, Mayo NE. Path to illness intrusiveness: what symptoms affect the life of people living with multiple sclerosis? Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98(7):1357–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2017.03.012.

Roessler RT. The illness intrusiveness model: rehabilitation implications. J Appl Rehabil Couns. 2004 Sep 1;35(3):22–7.

Horning MA, Shin JY, DiFusco LA, Norton M, Habermann B. Symptom progression in advanced Parkinson's disease: Dyadic perspectives. Appl Nurs Res. 2019;50:151193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2019.151193.

Bouça-Machado R, Maetzler W, Ferreira JJ. What is functional mobility applied to Parkinson’s disease? J Parkinson's Dis. 2018;8(1):121–30. https://doi.org/10.3233/JPD-171233.

Rascol O, Perez-Lloret S, Damier P, Delval A, Derkinderen P, Destée A, et al. Falls in ambulatory non-demented patients with Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Neural Transmission. 2015;122(10):1447–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-015-1396-2.

Choi SM, Jung HJ, Yoon GJ, Kim BC. Factors associated with freezing of gait in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Neurol Sci. 2019;40(2):293–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-018-3625-6.

Lee SJ, Kim SR, Chung SJ, Kang HC, Kim MS, Cho SJ, et al. Predictive model for health-related quality of life in patients with Parkinson's disease. Geriatr Nurs. 2018;39(2):204–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2017.09.001.

Spadaro L, Bonanno L, Di Lorenzo G, Bramanti P, Marino S. Health-related quality of life in Parkinson’s disease patients in northeastern Sicily, Italy: (An ecological perspective). Neural Regen Res. 2013;8(17):1615. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1673-5374.2013.17.010.

Sjödahl Hammarlund C, Westergren A, Åström I, Edberg AK, Hagell P. The impact of living with Parkinson’s disease: balancing within a web of needs and demands. Parkinson’s Dis. 2018;2018. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/4598651.

Soundy A, Stubbs B, Roskell C. The experience of Parkinson's disease: a systematic review and meta-ethnography. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014;2014:613592. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/613592.

DeCoster VA, Killian T, Roessler RT. Diabetes intrusiveness and wellness among elders: A test of the illness intrusiveness model. Educational Gerontology. 2013;39(6):371–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2012.700868.

Gusdal AK, Johansson-Pajala RM, Zander V, von Heideken Wågert P. Prerequisites for a healthy and independent life among older people: a Delphi study. Ageing Soc. 2020:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X20000306.

Tod AM, Kennedy F, Stocks AJ, McDonnell A, Ramaswamy B, Wood B, et al. Good-quality social care for people with Parkinson’s disease: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(2):e006813. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014006813.

Fereshtehnejad SM, Lökk J. Active aging for individuals with Parkinson’s disease: Definitions, literature review, and models. Parkinson’s Dis. 2014;2014. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/739718.

Udo DS. Active ageing: a concept analysis. Caribbean J Nurs. 2016;3(1):59–79.

Domènech-Abella J, Mundó J, Haro JM, Rubio-Valera M. Anxiety, depression, loneliness and social network in the elderly: Longitudinal associations from The Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA). J Affect Disord. 2019;246:82–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.12.043.

The Strobe Statement Organisation. https://www.strobe-statement.org/ Accessed 23 Feb 2022.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Professor Catriona Kennedy, Professor Fiona Murphy, Professor Susan Coote, Dr., Peter Boers, Mags Richardson CNS, and Mary Pat Butler for their contributions to; the early stages of this research design and a University of Limerick early researcher seed funding initiative. Dr. Jean Saunders’ expert guidance on statistical analysis is also recognised and greatly appreciated. Finally, we acknowledge and sincerely thank all survey participants for taking the time to complete the survey, and for their significant contributions to this study’s findings on factors influencing HRQoL for PwP.

Funding

The University of Limerick, Limerick, Ireland supported this research through an internal early researcher seed funding initiative.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IC designed the study, collected and analysed the data and led the writing of this manuscript. OD contributed to the study, provided feedback throughout and assisted with the manuscript writing. PM contributed to the study and survey design, provided feedback throughout and assisted with the manuscript writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research protocol was approved by University Hospital Limerick Research Ethics Committee, Limerick, Ireland who also provided approval to undertake the research. This approval was based on the ethical principles of beneficience/non-maleficience, justice, and autonomy. Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study. Consistent with ethical standards, participants were informed of the nature of the study, the researcher’s responsibilities, and their right to decline to partake in the study or withdraw at any time without risk of incurring penalties or prejudicial treatment. All participants consented to complete the survey based on the invitation letter, information sheet and return of completed questionnaire. Research methods were carried out in accordance with relevant regulations and Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines [77].

Consent for publication

Is not required as all participants are unidentified and there are no individual details reported within the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Kolmogorov-Smirnov Statistics. Details-Portrait presentation of results.

Additional file 2.

HRQoL descriptives. Details- Landscape presentation of results.

Additional file 3.

Hierarchical multiple regression analysis. Details- Landscape presentation of results.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Cassidy, I., Doody, O. & Meskell, P. Exploring factors that influence HRQoL for people living with Parkinson’s in one region of Ireland: A cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr 22, 994 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03612-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03612-4