Abstract

Background

Inappropriate prescribing of medications and polypharmacy among older adults are associated with a wide range of adverse outcomes. It is critical to understand the attitudes towards deprescribing—reducing the use of potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs)—among this vulnerable group. Such information is particularly lacking in low - and middle-income countries.

Methods

In this study, we examined Chinese community-dwelling older adults’ attitudes to deprescribing as well as individual-level correlates. Through the community-based health examination platform, we performed a cross-sectional study by personally interviews using the revised Patients’ Attitudes Towards Deprescribing (rPATD) questionnaire (version for older adults) in two communities located in Suzhou, China. We recruited participants who were at least 65 years and had at least one chronic condition and one prescribed medication.

Results

We included 1,897 participants in the present study; the mean age was 73.8 years (SD = 6.2 years) and 1,023 (53.9%) were women. Most of older adults had one chronic disease (n = 1,364 [71.9%]) and took 1–2 regular drugs (n = 1,483 [78.2%]). Half of the participants (n = 947, 50%) indicated that they would be willing to stop taking one or more of their medicines if their doctor said it was possible, and 924 (48.7%) older adults wanted to cut down on the number of medications they were taking. We did not find individual level characteristics to be correlated to attitudes to deprescribing.

Conclusions

The proportions of participants’ willingness to deprescribing were much lower than what prior investigations among western populations reported. It is important to identify the factors that influence deprescribing and develop a patient-centered and practical deprescribing guideline that is suitable for Chinese older adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) can lead to adverse drug events, drug interactions, falls, fractures, functional or cognitive impairment, poor adherence, hospitalization, and excessive medical costs, especially in older patients with comorbidities [1,2,3,4,5]. To limit such risks, deprescribing, which is defined as a patient-centered strategy of drug withdrawal aimed at improving health outcomes by discontinuing prescriptions that are either hazardous or no longer required [6], has been proposed as a method of addressing concurrent use of multiple medications [7]. It is a consensus that patients should be engaged in the prescribing process since patient-centered treatment could optimize health outcomes [8, 9]. Therefore, having a better understanding of the attitudes towards medication use and willingness to deprescribe among older adults would be one of the necessary steps to implement deprescribing in geriatric practice.

The revised Patients’ Attitudes Towards Deprescribing (rPATD) questionnaire was recently developed to assess patients’ perceptions about medication use and deprescribing [10]. To date, rPATD studies have been conducted across a number of countries including Australia [11], Singapore [12], Ethiopia [13], Malaysia [14], Netherlands [15], United States [16] and United Kingdom [17]. Studies conducted in different countries have shown that the acceptance rates of deprescribing range from 29% [17] to 93% [18].

Though many western countries have adopted the deprescribing approach, evidence on deprescribing is lacking from developing countries, suggesting the concept is yet novel [19, 20]. Moreover, no previous study has explored the older patients’ attitudes toward deprescribing in China, which has the largest older population in the world and is expected to experience the fastest growth of population aging in the next 20 years [21]. This study aimed to identify Chinses community-dwelling older adults’ attitudes and beliefs towards deprescribing by rPATD questionnaire, and to explore socio-demographic and lifestyle factors for attitudes towards deprescribing.

Methods

Study design, setting and participants

This cross-sectional study was conducted in two community health centers in Suzhou, China from October 2020 to April 2021 (Wumen Bridge South Ring Community and Loujiang Community). All older residents (at least 65 years) living in the above-mentioned two communities were invited to participate in regular physical examinations, during which blood and urine samples and self-administered health questionnaires were collected. All these individuals were screened by trained nurses for eligibility to participate in our study. Eligibility criteria include: (1) no significant cognitive impairment, (2) no terminal illness with a life expectancy less than 12 months, and (3) willing to participate. A face-to-face interview was conducted by at the physical examination site for each participant to collect survey data. Four nurses from Suzhou Municipal Hospital conducted all interviews. All participants were given informed consent prior to being enrolled in the study.

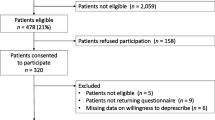

A total of 2778 older individuals participated in the questionnaire survey. Of these participants, we included 2733 participants who were 65 years and over, had one or more chronic conditions and took one or more prescription medications.

Deprescribing attitudes

Older adults’ attitudes towards deprescribing were assessed by eight questions from the validated rPATD questionnaire (version for older adults) [10, 16]. The rPATD questionnaire was developed to measure individuals’ attitudes, beliefs, and experiences with their medications and willingness to medication discontinuation [10]. The eight questions are as follow: (1) If my doctor said it was possible, I would be willing to stop one or more of my regular medicines; (2) I would like to reduce the number of medicines I am taking; (3) I have a good understanding of the reasons I am taking each of my medicines; (4) I believe that all of my medicines are necessary; (5) I would be willing to stop a medicine that I have been taking for a long time; (6) I feel that I am taking a large number of medicines; (7) I get stressed whenever changes are made to my medicines; (8) I feel that I may be taking one or more medicines that I no longer need. The response options were modified from the rPATD to a 4-point Likert scale, and four response options were available for each of these eight statements: “highly agree,“ “agree,“ “disagree,“ and “highly disagree.“ The results are self-reported by the participants. In this study, the rPATD questionnaire was first translated into Chinese by two independent bilingual translators and back to English to ensure that the translated version gave the proper meaning.

Other variables

During the interview, in addition to participants’ attitudes towards deprescribing, data on sociodemographic characteristics such as participants’ age, gender, the highest level of education attained, marital status, living arrangements, financial assistance, and clinical characteristics such as height, weight, and blood pressure were also captured.

Statistical analysis

Data were entered into Epidata 4.6.0.6 and analyzed in Stata 16.0. Participants’ characteristics and rPATD responses were reported using descriptive statistics. Categorical variables were reported as frequency and percentage, and continuous variables were reported as mean and standard deviation. Participants’ responses to the rPATD questions were dichotomized to agree (highly agree or agree) or disagree (disagree or highly disagree). Similar to a previous study by Reeve et al. [16], two of the scale items were chosen as the major outcomes of interest because they gave an overview of the individual’s attitudes to deprescribing. “If my doctor said it was possible, I would be willing to stop one or more of my regular medicines” and “I would like to reduce the number of medicines I am taking,“ are referred to as “willingness to discontinue” and “wanting to reduce,“ respectively [16]. We excluded participants with any missing item of the rPATD questionnaire. To assess the association between those who completely answered the questionnaire and who didn’t, the bivariate analyses were conducted. We used logistic regression to analyze unadjusted correlations between the two primary statements and respondents’ demographic and clinical characteristics. After adjusting for demographic and clinical factors, multivariable regression models were used to investigate the likelihood of willingness to discontinue and wanting to reduce. P ⩽0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Sample characteristics

Among the recruited 2733 participants, we excluded 836 participants who didn’t completely answer the rPATD questionnaire. Table S1 showed that there were not huge differences between the included and excluded participants. Of the 1,897 eligible participants, the median age was 73.8 years; 29.6% (n = 561) were 65–69 years, 30.3% (n = 575) were 70–74 years, 20.6% (n = 392) were 75–79 years, and 19.5% (n = 369) were at least 80 years (Table 1). There were 1,023 females (53.9%). Nearly 80% were married and living with a spouse and slightly over 85% lived with family members; only 27.0% (n = 509) reported having attended high school education and above. The three most common chronic conditions were hypertension (90.1%), diabetes mellitus (24.7%) and hyperlipidemia (5.8%). Approximately 6% had three or more chronic medical conditions, and 21.8% took three or more regular medications. Moreover, 6.5% of the participants reported fair or poor self-rated health.

Older adults’ beliefs and attitudes toward deprescribing

Participants’ responses to the rPATD questionnaire were presented in Fig. 1. Nearly all participants thought they had a good understanding of the reasons why they were taking these medicines (98.8%) and believed that all their medications were necessary (99.4%). There were 48.7% of the participants had the desire to reduce the number of medications they were taking, and half of the participants reported that they would be willing to stop one or more of their medicines if their physician said it was possible. In addition, 63.5% of the participants would be willing to stop a medicine they have been taking for a long time. Moreover, 38.0% considered that they were taking many medications, 15.5% felt that they were taking medications that they no longer needed, and 34.8% of the respondents reported that they got stressed whenever changes were made to their medicines.

As shown in Table 2, there were no demographic and clinical characteristics associated with willingness to stop and wanting to reduce. An adjusted multivariate analysis for all the eight questions was shown in the supplementary Table 2.

Discussion

Summary and comparison with existing literature

Overall, we found that although almost all participants had a firm belief in the necessity of their medications and thought they had a good understanding of the medicines they were taking, still half of them were willing to stop one or more of their medications if their doctor said it was possible, and almost half of them expressed willingness of reducing the number of medicines they were taking. These results concur with previous rPATD studies which demonstrated that the majority of participants agreed with deprescribing proposed by a doctor whilst also be satisfied with current medicines [22,23,24,25].

We found that 50% of community-dwelling older adults in China were willing to deprescribing, which was lower than that in other Asian and western countries. In Asian countries, Kua KP et al. [14] found that 67.7% of older adults in Malaysia and Kua CH et al. [12] found that 83.0% of older adults in Singapore were willing to stop one or more of their medications if their doctor said it was possible. The level of older adults’ willingness to deprescribing was generally higher in western countries such as 92% in the United States [16], 88% in Australia [26], and 87% in Denmark [27]. Also, a recent systematic review suggested that 84% of older adults were willing to deprescribe [28]. These differences may be explained by the fact that participants in our study were in better health. Indeed, nearly 80% of patients in the current study took fewer than three medications, and older adults in Kua KP et al. study were taking a median of three medications, while the median number of patients’ daily medications was 11, 8, and 6 in Reeve et al. [18], Carina et al. [27] and Sirois et al. studies [29] respectively.

One plausible explanation for the relatively low willingness to deprescribing in the present study is that physicians in China may have a strong influence on older adults’ attitudes towards medication use and deprescribing [30]. Patients in China are more likely to conform to physicians’ recommendations despite concerns about their medications [31, 32]. Meanwhile, Chinese physicians still tended to use complicated and long-term medication regimens in treatment [32]. Moreover, the proportion of older adults taking traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) was high in China and older adults have a high adherence to TCM [31, 33]. This might help explain why Chinese older adults were less willing to reduce medication use than their Western counterparts. Besides, fear, low health literacy, time limitations, professional hindrances, and belief that their medicines are appropriate are also barriers to deprescribing in practice [26, 34,35,36].

We did not find age, the number of medications uses, or the number of medical conditions to be associated with older adults’ willingness to stop a medication. This is consistent with Oktora et al. systematic review [20] which declared that the patients’ sex or education were not associated with their attitudes toward deprescribing generally and age was not associated with their attitudes at individual level. The current investigation could not identify characteristics that could select individuals who are more favorable toward deprescribing. This implies that to provide patient-centered care, all residents should be evaluated individually for deprescribing, regardless of how many medications they are taking or how old they are.

Strengths and limitations

This study is among the first to use a validated multidimensional questionnaire to measure older individuals’ willingness to deprescribing in China. We acknowledged several limitations. First, as only a portion of the rPATD questionnaire was used, factor scores could not be calculated. In addition, the rPATD questionnaire was originally designed in English and had not been validated in China previously. Moreover, our findings need to be interpreted cautiously because our study was conducted in one study site, which may not be representative of the entire Chinese older population. Lastly, as the participation was based on volunteers, acceptance rates in studies may be biased by individuals who are willing to consent to study participation.

Implications for clinical practice and future research

Although the willingness of deprescribing among community-dwelling older adults is relatively low in this study, practitioners should not dismiss deprescribing opportunities due to the benefits of deprescribing such as increasing the patient’s engagement in medication therapy management and improving adherence possibly through reducing polypharmacy [13, 37]. Currently, the guideline for deprescribing have been developed in Australia [4, 38, 39]. We should adapt this guideline to the current situation in China and draw up a patient-centered and practical deprescribing guideline that is suitable for Chinese older adults.

Further research uses complete rPATD questionnaire and conducted with representative sample is needed. Studies that explore the predictors of older adults’ attitudes towards deprescribing is also required. Furthermore, to ascertain the safety and efficacy of the deprescribing, feasibility and implementation research will be needed, and long-term outcomes should be determined while taking economic factors into account.

Conclusions

This study suggests that half of the community-dwelling older adults were willing to cease a medication if their physician thought possible, and almost half of them would like to reduce the number of medicines they were taking. The attitudes toward deprescribing were not associated with sex, age, number of medications, or number of chronic diseases. Future studies with more advanced method and more representative samples were needed. Additionally, we should adapt the guideline developed in Australia to the current situation in China and draw up a patient-centered and practical deprescribing guideline that is suitable for Chinese older adults.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available as this would be in conflict with the informed consent given by the participants but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- PIMs:

-

Potentially Inappropriate Medications

- rPATD:

-

revised Patients’ Attitudes Towards Deprescribing

- TCM:

-

traditional Chinese medicine

References

Olsson IN, Runnamo R, Engfeldt P: Medication quality and quality of life in the elderly, a cohort study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2011, 9:95.

Muhlack DC, Hoppe LK, Weberpals J, Brenner H, Schöttker B: The Association of Potentially Inappropriate Medication at Older Age With Cardiovascular Events and Overall Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2017, 18(3):211–220.

Turgeon J, Michaud V, Steffen L: The Dangers of Polypharmacy in Elderly Patients. JAMA Intern Med 2017, 177(10):1544.

Scott IA, Hilmer SN, Reeve E, Potter K, Le Couteur D, Rigby D, Gnjidic D, Del Mar CB, Roughead EE, Page A et al: Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy: the process of deprescribing. JAMA Intern Med 2015, 175(5):827–834.

Page AT, Falster MO, Litchfield M, Pearson SA, Etherton-Beer C: Polypharmacy among older Australians, 2006–2017: a population-based study. Med J Aust 2019, 211(2):71–75.

Page A, Clifford R, Potter K, Etherton-Beer C: A concept analysis of deprescribing medications in older people. Journal of Pharmacy Practice and Research 2018, 48(2):132–148.

Duncan P, Duerden M, Payne RA: Deprescribing: a primary care perspective. European Journal of Hospital Pharmacy 2017, 24(1):37–42.

Griffin SJ, Kinmonth AL, Veltman MW, Gillard S, Grant J, Stewart M: Effect on health-related outcomes of interventions to alter the interaction between patients and practitioners: a systematic review of trials. Ann Fam Med 2004, 2(6):595–608.

Cross AJ, Etherton-Beer CD, Clifford RM, Potter K, Page AT: Exploring stakeholder roles in medication management for people living with dementia. Res Social Adm Pharm 2021, 17(4):707–714.

Reeve E, Low LF, Shakib S, Hilmer SN: Development and Validation of the Revised Patients’ Attitudes Towards Deprescribing (rPATD) Questionnaire: Versions for Older Adults and Caregivers. Drugs Aging 2016, 33(12):913–928.

Reeve E, Low LF, Hilmer SN: Attitudes of Older Adults and Caregivers in Australia toward Deprescribing. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019, 67(6):1204–1210.

Kua CH, Reeve E, Tan DSY, Koh T, Soong JL, Sim MJL, Zhang TY, Chen YR, Ratnasingam V, Mak VSL et al: Patients’ and Caregivers’ Attitudes Toward Deprescribing in Singapore. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2021, 76(6):1053–1060.

Tegegn HG, Tefera YG, Erku DA, Haile KT, Abebe TB, Chekol F, Azanaw Y, Ayele AA: Older patients’ perception of deprescribing in resource-limited settings: a cross-sectional study in an Ethiopia university hospital. BMJ Open 2018, 8(4):e020590.

Kua KP, Saw PS, Lee SWH: Attitudes towards deprescribing among multi-ethnic community-dwelling older patients and caregivers in Malaysia: a cross-sectional questionnaire study. Int J Clin Pharm 2019, 41(3):793–803.

Edelman M, Jellema P, Hak E, Denig P, Blanker MH: Patients’ Attitudes Towards Deprescribing Alpha-Blockers and Their Willingness to Participate in a Discontinuation Trial. Drugs Aging 2019, 36(12):1133–1139.

Reeve E, Wolff JL, Skehan M, Bayliss EA, Hilmer SN, Boyd CM: Assessment of Attitudes Toward Deprescribing in Older Medicare Beneficiaries in the United States. JAMA Intern Med 2018, 178(12):1673–1680.

Scott S, Clark A, Farrow C, May H, Patel M, Twigg MJ, Wright DJ, Bhattacharya D: Attitudinal predictors of older peoples’ and caregivers’ desire to deprescribe in hospital. BMC Geriatr 2019, 19(1):108.

Reeve E, Wiese MD, Hendrix I, Roberts MS, Shakib S: People’s Attitudes, Beliefs, and Experiences Regarding Polypharmacy and Willingness to Deprescribe. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2013, 61(9):1508–1514.

Shrestha S, Giri R, Sapkota HP, Danai SS, Saleem A, Devkota S, Shrestha S, Adhikari B, Poudel A: Attitudes of ambulatory care older Nepalese patients towards deprescribing and predictors of their willingness to deprescribe. Ther Adv Drug Saf 2021, 12:20420986211019309.

Oktora MP, Edwina AE, Denig P: Differences in Older Patients’ Attitudes Toward Deprescribing at Contextual and Individual Level. Front Public Health 2022, 10:795043.

World population prospects, the 2019 revision〔EB/OL〕 [https://population.un.org/wpp/Publications/]

Reeve E, Wiese MD, Hendrix I, Roberts MS, Shakib S: People’s attitudes, beliefs, and experiences regarding polypharmacy and willingness to Deprescribe. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013, 61(9):1508–1514.

Galazzi A, Lusignani M, Chiarelli MT, Mannucci PM, Franchi C, Tettamanti M, Reeve E, Nobili A: Attitudes towards polypharmacy and medication withdrawal among older inpatients in Italy. Int J Clin Pharm 2016, 38(2):454–461.

Qi K, Reeve E, Hilmer SN, Pearson SA, Matthews S, Gnjidic D: Older peoples’ attitudes regarding polypharmacy, statin use and willingness to have statins deprescribed in Australia. Int J Clin Pharm 2015, 37(5):949–957.

Kalogianis MJ, Wimmer BC, Turner JP, Tan EC, Emery T, Robson L, Reeve E, Hilmer SN, Bell JS: Are residents of aged care facilities willing to have their medications deprescribed? Res Social Adm Pharm 2016, 12(5):784–788.

Gillespie R, Mullan J, Harrison L: Attitudes towards deprescribing and the influence of health literacy among older Australians. Prim Health Care Res Dev 2019, 20:e78.

Lundby C, Glans P, Simonsen T, Søndergaard J, Ryg J, Lauridsen HH, Pottegård A: Attitudes towards deprescribing: The perspectives of geriatric patients and nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc 2021, 69(6):1508–1518.

Weir KR, Ailabouni NJ, Schneider CR, Hilmer SN, Reeve E: Consumer attitudes towards deprescribing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2022;77(5):1020–34.

Sirois C, Ouellet N, Reeve E: Community-dwelling older people’s attitudes towards deprescribing in Canada. Res Social Adm Pharm 2017, 13(4):864–870.

Wang J, Feng Z, Dong Z, Li W, Chen C, Gu Z, Wei A, Feng D: Does Having a Usual Primary Care Provider Reduce Polypharmacy Behaviors of Patients With Chronic Disease? A Retrospective Study in Hubei Province, China. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12:802097.

Lai X, Zhu H, Huo X, Li Z: Polypharmacy in the oldest old (≥ 80 years of age) patients in China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr 2018, 18(1):64.

Tian F, Liao S, Chen Z, Xu T: The prevalence and risk factors of potentially inappropriate medication use in older Chinese inpatients with multimorbidity and polypharmacy: a cross-sectional study. Ann Transl Med 2021, 9(18):1483.

Chan K, Zhang H, Lin ZX: An overview on adverse drug reactions to traditional Chinese medicines. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2015, 80(4):834–843.

Reeve E, To J, Hendrix I, Shakib S, Roberts MS, Wiese MD: Patient barriers to and enablers of deprescribing: a systematic review. Drugs Aging 2013, 30(10):793–807.

Anderson K, Stowasser D, Freeman C, Scott I: Prescriber barriers and enablers to minimising potentially inappropriate medications in adults: a systematic review and thematic synthesis. BMJ Open 2014, 4(12):e006544.

Turner JP, Edwards S, Stanners M, Shakib S, Bell JS: What factors are important for deprescribing in Australian long-term care facilities? Perspectives of residents and health professionals. BMJ Open 2016, 6(3):e009781.

Page AT, Clifford RM, Potter K, Schwartz D, Etherton-Beer CD: The feasibility and effect of deprescribing in older adults on mortality and health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2016, 82(3):583–623.

Scott IA, Gray LC, Martin JH, Mitchell CA: Minimizing inappropriate medications in older populations: a 10-step conceptual framework. Am J Med 2012, 125(6):529–537.e524.

Reeve E, Thompson W, Farrell B: Deprescribing: A narrative review of the evidence and practical recommendations for recognizing opportunities and taking action. Eur J Intern Med 2017, 38:3–11.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Suzhou Municipal Hospital, Gusu District Wumenqiao street Nanhuan community Health Service Center and Gusu District Pingjiang street Loujiang community Health Service Center for their assistance in the recruitment of participants. Additionally, we would like to express our gratitude to the Suzhou Municipal Science and Technology Bureau and Suzhou Healthcare Commission Science and Technology Project for providing funds to perform this study.

Funding

An unconditional grant was provided by the Suzhou Municipal Science and Technology Bureau (SS2019069), and the Suzhou Healthcare Commission Science and Technology Project (LCZX201911), they had no role in the execution of this study or in the drafting of the article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.T, MH.W, L.Z and CK.W: research idea and study design. XR.P, Q.S, CJ.L and L.Z: participants recruitment and questionnaires collection. J.T and Y.W: J.T input 3/4 of the questionnaires into Epidata and Y.W input 1/4 of the questionnaires. J.T and MH.W: analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing. L.Z and CK.W: supervision. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Suzhou Municipal Hospital Human Research and Ethics Committees granted ethics approval to this study (K-2020-019-K01). Informed consent was obtained from all participants. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Supplement Table 1.Comparison between included and excluded participants. Supplement Table 2. Adjusted associationsbetween older adults’ demographic and clinical characteristics and theirattitudes toward deprescribing. Supplementary Table 3.STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE)checklist for cross-sectional studies.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Tan, J., Wang, M., Pei, X. et al. Continue or not to continue? Attitudes towards deprescribing among community-dwelling older adults in China. BMC Geriatr 22, 492 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03184-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03184-3