Abstract

Background

Home rehabilitation is a growing rehabilitation service in many countries, but scientific knowledge of its components and outcomes is still limited. The aim of this study was to investigate; 1) which changes in functioning and self-rated health could be identified in relation to a home rehabilitation program in a population of community-dwelling citizens, and 2) how socio-demographic factors, health conditions and home rehabilitation interventions were associated to change in functioning and self-rated health after the home rehabilitation program.

Method

The sample consisted of participants in a municipal home rehabilitation project in Sweden and consisted of 165 community-dwelling citizens. General Linear Models (ANOVA repeated measures) was used for identifying changes in rehabilitation outcomes. Logistic regressions analysis was used to investigate associations between rehabilitation outcomes and potential factors associated to outcome.

Result

Overall improvements in functioning and self-rated health were found after the home rehabilitation program. Higher frequencies of training sessions with occupational therapists, length of home rehabilitation, and orthopaedic conditions of upper extremities and spine as the main health condition, were associated with rehabilitation outcomes.

Conclusion

The result indicates that the duration of home rehabilitation interventions and intensity of occupational therapy, as well as the main medical condition may have an impact on the outcomes of home rehabilitation and needs to be considered when planning such programs. However, more research is needed to guide practice and policymaking.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The increased proportion of older adults in the population is expected to have an impact on healthcare systems worldwide [1, 2]. This has resulted in the implementation of home rehabilitation programs to promote independence [3,4,5,6,7] and to support citizens to stay-in-place [8,9,10] in Sweden and many other countries [11]. Home rehabilitation is not a unitary concept and programs can vary in how they are called, and its organization, content and target group [12]. In Sweden, occupational therapists and physiotherapists are the core practitioners in municipal home rehabilitation, and they work in close collaboration with home care services for adults of all ages [12,13,14], especially for older adults [14]. Different home rehabilitation programs share however common characteristics such as having a limited duration [8, 15], and being intensive, multidisciplinary, person-centred and goal-oriented [8, 15, 16]. Their common aim is to promote independence and support older adults to remain in their homes for as long as possible [8, 9]. Home rehabilitation programs have shown positive effects such as improved ADL skills, self-reported activity performance, quality of life [9, 17, 18] and decreased dependence on home care services [4]. Some studies do however report a lack of long-term effects [19]. Knowledge is also limited as to which components of home rehabilitation programs lead to positive results [12] and if some client groups benefit from the intervention more than others [8]. There are indications that women are more motivated in home rehabilitation after fractures and thus achieve better outcomes than men [20]. The optimal intensity and duration of home rehabilitation programs are also debated [16].

To guide home rehabilitation programs, research is needed on how different factors such as gender, types and length of intervention, and health conditions affect the outcome [15]. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate; 1) which changes in functioning and self-rated health could be identified in relation to a home rehabilitation program in a population of community-dwelling citizens, and 2) how socio-demographic factors, health conditions and home rehabilitation interventions are associated to changes in functioning and self-rated health after a home rehabilitation program.

Method

The home rehabilitation intervention

The present study analyses already collected data derived from a home rehabilitation improvement project in a Swedish municipality with approximately 140,000 citizens. The project was initiated by the municipality to develop their rehabilitation program and was conducted without a control group. The project involved team-based rehabilitation executed by occupational therapists, physiotherapists and rehabilitation assistants in the person’s home and neighbourhood. An overview of the home rehabilitation interventions is presented in Fig. 1. The interventions had a limited time duration and were based on the participants’ own goal. It also included collaboration with other caregivers. For example, home care staff sometimes also assisted with training.

Participants

Community-dwelling adults that were assessed to need rehabilitation and lived in a selected geographical area (mainly urban and suburban areas of approximately 47,000 inhabitants) were eligible for the municipal home rehabilitation program. Between 2015 and 2019, a total 212 adults participated in the program from different ages and with a range of health conditions. The participants gave informed consent to participate in the municipality project and each received up to 12 weeks of home rehabilitation.

For the purpose of this present study, access to de-identified data was granted by the municipality in line with Swedish laws and regulations [21]. The Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Dnr: 2019–00706) approved that the data would be used for research.

Data collection

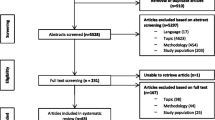

During the rehabilitation program, data were collected by the occupational therapists and physiotherapists involved. For this study, the municipality provided the collected and de-identified data from three points of time; baseline (T1), at the end of home rehabilitation intervention (T2) and at 2-month follow-up (T3). A total of 165 participants with data from T1 and T2 were available for analysis for this study (See Fig. 2). Twenty persons did not have a measurement point at T2 due to an extension in their training period and were therefore excluded from our study.

Dependent variables: rehabilitation outcomes

Functioning in activities of daily living

Sunnaas Activity of Daily Living Index (Sunnaas ADL index) examines the person’s functioning in daily activities [22] and was one of two measures of functioning used. The Sunnaas ADL Index contains ratings of 12 specific daily activities, including eight personal activities of daily living (PADL) and four instrumental activities of daily living (IADL). The level of independence is scored from: 3 = completely independent, 2 = independent but requires aids or adapted environment, 1 = partly dependent of another person and 0 = completely dependent on another person [23]. The Sunnaas ADL index is considered a reliable and valid assessment of function at the activity level [23,24,25].

For this study, an ADL index was created including the items feeding, indoor mobility, toilet management, transfer, dressing/undressing, grooming, cooking, bath/shower, housework, and outdoor mobility. The variables continence and communication were considered less relevant as outcomes of home rehabilitation interventions and were not included in our ADL-index. The score for each included item was dichotomized as 0 = independent (score 3–2) vs. 1 = dependent (score 1–0). The dichotomized scores were summarized, thus giving an ADL index value from 0 to 10. In addition, the ADL index differences between T1 and T3 was calculated and dichotomized to create a variable where 0 = no change/deterioration and 1 = improvement over time. Cronbach’s alpha analysis demonstrated good inter-item reliability of the ADL-index used in this study (0.85).

General motor functioning dependence

The General Motor Function assessment scale (GMF) includes 11 mobility functions and 10 upper limb functions [26] and three different subscales: function-related dependence, pain and insecurity. For this study, we used the dependence subscale alone, hereafter GMF dependence. In this measure functioning, degrees of dependence are assessed on a two-point scale for some functions (specified in Table 2); 0 = independent, 1 = help from 1 person/unable, while other functions were measured on a three-point scale; 0 = independent, 1 = help from 1 person, 2 = help from 2 persons/unable (Table 2). The GMF has shown good validity [27, 28], sensitivity [27] and reliability [26].

For this study, two GMF dependence indexes were created. The first index, GMF dependence mobility, included the 11 mobility functions ranging from turning over in bed to climbing stairs and transfer outdoors. Each item was rated 0 = independent (score 0) or 1 = dependent (score 1–2) (Cronbach’s alpha = 0, 70). The second index, GMF dependence upper limb, included the 10 variables for arm movements and grip functions. Items were rated as 0 = independent (score 0) or 1 = dependent (score 1–2) (Cronbach’s alpha = 0, 70). Even here, the difference between T1-T3 was calculated and dichotomized to create a variable in terms of 0 = no change/deterioration vs. 1 = improvement over time.

Self-rated health

Self-rated health was measured through EQ VAS, which is included in the European Quality of Life Five Dimension Five Level Scale (EQ-5D-5L) [29]. The occupational therapist or physiotherapist performing the rehabilitation asked participants to complete the EQ-5D-5L form, which could then be posted in a pre-stamped envelope addressed to the municipality development unit. In EQ VAS in particular, participants assess their health status on the present day using a vertical visual analogue scale ranging from 0 “the worst imaginable health” to 100 “the best imaginable health” [29].

In this study we use the EQ VAS as a dependent continuous variable for self-rated health. The EQ-5D-5L has demonstrated satisfactory reliability, validity and responsiveness in older adults [30].

Independent variables: factors potentially associated to rehabilitation outcomes

Data on participant characteristics were their age (years), gender (male/female), living situation (living alone/cohabiting), main reasons for home rehabilitation, number of training sessions by rehabilitation staff and length of home rehabilitation in weeks. The main reason for home rehabilitation was defined by the health condition described in professional assessments, diagnoses and/or the person’s own experienced problems leading to the need for rehabilitation.

For this study, data were categorized using information on current diagnosis, medical condition, and affected body part (e.g., mobility difficulties due to hip fracture). If specific information about current diagnosis or medical condition was missing, the person’s medical history was used as a guide to indicate an appropriate category. Seven categories were identified; conditions in the circulatory and respiratory systems (e.g., chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, myocardial infarction), mobility limitations including fall risk (condition not specified or e.g., fall trauma, impaired balance), multimorbidity and/or frailty (a complex situation or conditions involving problems in several body regions, e.g., cancer, fibromyalgia), neurological conditions excl. stroke (e.g., multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease), orthopaedic conditions upper extremities and spine (e.g., vertebral compressions, shoulder fracture), orthopaedic conditions lower extremities and pelvis (e.g., femoral amputation, knee osteoarthritis) and stroke (acute and post).

Analyses

General Linear Models (ANOVA repeated measures) were first performed to analyse changes over time in functioning (ADL, GMF dependence) and in self-rated health (EQ VAS) between baseline and at the end of home rehabilitation intervention (T1-T2) and between baseline and 2-month follow-up (T1-T3). Logistic regression analyses were performed to investigate associations between independent variables and the outcomes of functioning and self-rated health in terms of no change/deterioration vs. improvement. Firstly, bivariate analyses were performed to investigate associations for each variable in relation to the outcomes. In the next step, multivariate analyses were performed for all independent variables in the model. Within the variable main reason for rehabilitation, multimorbidity and/or frailty were chosen as the reference category.

The number of training sessions that each participant received from an occupational therapist and physiotherapist per week during home rehabilitation were analysed through logistic regression models. Visits by rehabilitation assistants were few and consequently these were not included in the regression models. Potential interaction between intensity and duration was tested by adding an interaction term (number of training session per number of weeks) in each logistic regression model. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistic version 26.

Results

Descriptive results

A description of baseline characteristics, home rehabilitation interventions and baseline rehabilitation outcomes are presented in Table 1. The participants had a mean age of 80 years and the majority were women. Half of the participants lived alone, although there is a gender difference as majority of the men lived together with someone, and majority of the women lived alone. Orthopaedic conditions (lower extremities and pelvis) were the most frequent reasons for needing home rehabilitation. The participant received an average of 2.8 training sessions per week and the average duration of the training was 8.5 weeks. The rehabilitation outcome scores demonstrated that the participants had a moderate to mild disability at baseline.

Changes in functioning and self-rated health

The result from the GLM repeated measures is presented in Table 2. There are overall statistically significant improvements in activities of daily living at the end of the home rehabilitation intervention (T2) and at the two-month follow-up (T3). The change in ability to eat is only statistically significant between T1 and T3. The ADL index demonstrated significant improvements between both T1 and T2 (3.47; 2.20, a difference of 1.27) and between T1 and T3 (3.47; 2.10, a difference of 1.37). The GMF dependence mobility index showed statistically significant improvements between both T1 and T2 (1.69; 0.85, a difference of 0.84) and between T1 and T3 (1.69; 0.66, a difference of 1.03). The GMF dependent upper limb index demonstrated statistically significant improvement between both T1 and T2 (0.58; 0.43, a difference of 0.15) and between T1 and T3 (0.58; 0.40, a difference of 0.18). EQ VAS showed significant improvement between both T1 and T2 (55.11; 62.62, a difference of 7.51) and between T1 and T3 (55.11; 66.42, a difference of 11.31).

Factors associated to rehabilitation outcomes

The results of the bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses with the ADL outcomes are presented in Table 3. Having an orthopaedic condition in the upper extremities and spine was associated with increased functioning in ADL after rehabilitation. The relationship was slightly attenuated in the multivariate model that included gender, age, living situation, number of training sessions and length in weeks and was no longer statistically significant (p = 0.052). The result also points to an association between orthopaedic conditions (lower extremities and pelvis) (OR 2.58; 95% CI .99–6.71) and an increase in ADL after intervention, although not statistically significant at 5% level (Table 3).

Displayed in Table 4, the bivariate logistic regression analysis showed that higher frequencies of training sessions per week by an occupational therapist were associated with improvement in mobility outcomes (OR 2.09, 95% CI 1.12–3.91). The corresponding result for training sessions per week by a physiotherapist displayed a tendency in the same direction (OR 1.70, 95% CI .99–2.91). The relationship between training sessions by an occupational therapist and mobility functions did not remain statistically significant in the multivariate model. When it comes to living condition, the result points towards an association with increased mobility function for those living together with someone (OR 1.74, 95% CI .91–3.33), as compared to those living alone. However, this was not statistically significant at 5% level (Table 4).

Table 5 presents the bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis with GMF dependence upper limb as the outcome. A longer duration of home rehabilitation (number of weeks) was a factor related to improvement in upper limb function, and an association between orthopaedic conditions (lower extremities and pelvis) and upper limb function was found. Both relations remained statistically significant in the multivariate model.

The results of the bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses with self-rated health as the outcome are presented in Table 6. No statistically significant associations were found between the independent variables and self-rated health. No statistically significant interaction was found between number of training sessions and duration of intervention (number of weeks) in the logistic regression models (not displayed).

Discussion

In this study we investigated changes in functioning and self-rated health in relation to a home rehabilitation program. We also investigated how socio-demographic factors, health conditions and intensity and duration of home rehabilitation interventions were associated to change in functioning and self-rated health after home rehabilitation. We found improvements in functioning and self-rated health after a home rehabilitation program and at 2-month follow-up. This is in line with several systematic reviews of home rehabilitation programs [31,32,33,34,35]. We found an association between higher frequencies of training sessions per week by an occupational therapist and improved mobility functions. This is in line with a study of stroke patients that found a positive correlation between the amount of training in minutes led professionals and outcomes in both ADL, motor functions and quality of life [36]. These indicate that the amount of training with professionals is a factor that needs to be considered when planning rehabilitation interventions, as it may have an impact on outcomes. Studies in Sweden have however shown that home rehabilitation interventions by occupational therapists and physiotherapists in Sweden consist of an average of five visits during a six-week period, which is a lower intensity than the home rehabilitation program in our study [14]. Our results would suggest that increasing in the intensity of professional training sessions in home rehabilitation may be necessary in clinical practice.

We also found an association between longer duration of training in weeks and improved upper limb functions. Although home rehabilitation programs are usually described as intensive interventions during a fixed duration [8, 15], there are definitions of home rehabilitation, such as in reablement, that emphasize multiple visits rather than the intervention’s time frame [16]. There are also few studies analysing the duration and frequency of training in home rehabilitation programs [33] and the time frame used in previous studies have varied from 4 to 12 weeks to 6 months [8, 15, 34, 35, 37]. Consequently, there is no consensus on the intensity and duration of home rehabilitation programs at present. To guide work in practical settings, more knowledge is needed to identify the duration and intensity where home rehabilitation programs are most effective [31, 33] as well as the possible relations to different outcomes.

In our study we found that intensive occupational therapy was a factor associated with improved mobility functions, and intensive physiotherapy also demonstrated a tendency in the same direction. Home rehabilitation teams usually vary in composition, with professionals from health- and social care [16]. Research suggests the inclusion of occupational therapists and physiotherapists [38], which is supported by our results. Interventions made by occupational therapists such as housing adaptations and provisions of mobility devices may explain why occupational therapy rather than physiotherapy was associated with mobility outcomes in our study [14]. However, more research is needed regarding outcomes related to specific professions [13, 39, 40].

Previous studies have shown that gender [20, 32], age [32] and diagnosis or condition [20] could affect the outcome of home rehabilitation programs. In our study, the participants’ gender, age or living situation were not associated with their rehabilitation outcomes. However, we found that participants with orthopaedic conditions in upper extremities and spine were significantly more likely to improve in ADL than the other participants, indicating some benefits for that client group in receiving home rehabilitation. An explanation for their improvement could be that these conditions often are associated with fewer residual conditions compared to e.g., stroke or multimorbidity.

While home rehabilitation programs generally should not be limited in terms of participants’ age or condition [16], some programs only include older adults (> 65) with home care services [31] and exclude persons with complex care needs (> 15 h home care per week) [5]. In Sweden where our study was conducted, home rehabilitation can be provided regardless of age or receipt of home care services [14]. Our study also included many different diagnoses and conditions in the analysis, while other studies only focus on a few of these. Further research is needed to determine whether specific client groups living in the community can benefit from intervention more than others, to guide policymaking and needs assessment. More knowledge is also needed on socio-demographic factors and health conditions, and how these affect outcomes to further improve home rehabilitation programs.

Strength and limitations

In this study, we analysed de-identified data from a real-life setting with a sample varying in age, gender, living situations and health conditions. This contributes to the strength and relevance of our study when results are implemented in practice. Our results can also be externally generalized to similar contexts.

The study sample was rather small yielding low precision in the estimated effect measures with wide confidence intervals. Furthermore, no control group was included. Together, this prevents us from drawing definitive conclusions, even though our results point to several implications for research and practice.

A strength of our study is that the data were collected with accepted and validated instruments. However, for older people with minor functional limitations, the GMF shows ceiling effects [28] which may have affected the outcomes. Another limitation in this study is that the occupational therapists and physiotherapists who performed the interventions were also those who collected the data. The relationship between rehabilitation staff and participants could have affected the objectivity of the data measurement. This being said, the municipal improvement project included clear and structured routines for data collection and data handling to ensure the reliability of the data. The home rehabilitation interventions were not designed to be standardised but were tailored to the individual’s goals, needs and context, using a person-centred approach. Consequently, it is difficult to know if and how other factors that were not measured could have affected the results of the intervention.

Conclusion

Overall improvements in functioning and self-rated health were found after a home rehabilitation program in a population of community-dwelling citizens. The result indicates that duration, intensity of occupational therapy and the main condition for rehabilitation may have an impact on the rehabilitation outcomes. Increased frequency of training sessions and longer duration of the program with professional rehabilitation staff, is vital to consider when implementing home rehabilitation programs. More research on home rehabilitation programs in different contexts, using a large sample and control groups is needed to further guide clinical practice and policymaking.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study were collected within a project run by the municipality of Jönköping, Sweden. Strong restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data used for this study could however be available from the authors upon reasonable request and if permission from the municipality of Jönköping is granted.

References

World Health Organization, World report on Aging and Health. 2015, Geneva: World Health Organization.

UNECE, United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. Innovative and Empowering Strategies for Care, Policy Brief on Ageing No. 15. Geneva. 2014.

Bauer A, Fernandez JL, Henderson C, Wittenberg R, Knapp M. Cost-minimisation analysis of home care reablement for older people in England: a modelling study. Health & Social Care in the Community. 2019;27(5):1241–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12756.

Lewin GF, Alfonso HS, Alan JJ. Evidence for the long term cost effectiveness of home care reablement programs. Clin Interv Aging. 2013;8:1273–81. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S49164.

Lewin, G., et al., A comparison of the home-care and healthcare service use and costs of older Australians randomised to receive a restorative or a conventional home-care service. 2014.

Langeland, E., et al., Modeller for hverdagsrehabilitering - en følgeevaluering i norske kommune; effekter for brukerne og gevinster for kommunene? [Models for everyday rehabilitation - a follow-up evaluation in Norwegian municipalities; effects for users and benefits for municipalities?]. 2016: Senter for omsorgsforskning, vest.

Gustafsson, U., et al., Hemrehabilitering för äldre i olika stora kommuner: Upplevd kvalitet, funktionsförändring, organisationsförutsättningar, resursförbrukning och statliga stimulansmedels betydelse för utvecklingen. [Home rehabilitation for the elderly in various large municipalities: perceived quality, functional change, organizational conditions, resource consumption and the importance of government stimulus funds for development] FoU-rapport 2010: 11. 2010, Växjö: FoU Kronoberg.

Aspinal F, Glasby J, Rostgaard T, Tuntland H, Westendorp RGJ. New horizons: Reablement - supporting older people towards independence. Age Ageing. 2016;45(5):574–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afw094.

Winkel A, Langberg H, Wæhrens EE. Reablement in a community setting. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37(15):1347–52. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2014.963707.

Ministry of Health and Social Affairs, Nationell handlingsplan för äldrepolitiken. [National action plan for elderly policy]. Prop. 1997/98:113. 1997, Regeringen.se: https://www.regeringen.se/rattsliga-dokument/proposition/1998/04/prop.-199798113/.

UNECE-United Nations Economic and Social Council, Ensuring a society for all ages: promoting quality of life and active ageing, ECE/AC.30/2012/3. 2012, Vienna Ministerial Declaration, Economic Commission for Europe,Working Group on Ageing, Ministerial Conference on Ageing, Vienna, 19 and 20 September 2012,.

Tuntland, H. and N.E. Ness, Hverdagsrehabilitering [Everyday rehabilitation]. 1. utg., 1. oppl. ed. 2014: Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk.

Zingmark M, Evertsson B, Haak M. The content of reablement: Exploring occupational and physiotherapy interventions. Br J Occup Ther. 2018;82(2):122–6.

Zingmark M, Evertsson B, Haak M. Characteristics of occupational therapy and physiotherapy within the context of reablement in Swedish municipalities: a national survey. Health Soc Care Commun. 2019;28(3):1010–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12934.

Cochrane A, et al., Time-limited home-care reablement services for maintaining and improving the functional independence of older adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2016(Issue 10.).

Metzelthin SF, Rostgaard T, Parsons M, Burton E. Development of an internationally accepted definition of reablement: a Delphi study. Ageing Soc. 2020:1-62. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X20000999.

Tuntland H, et al. Reablement in community-dwelling older adults: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:1–11.

Langeland E, Tuntland H, Folkestad B, Førland O, Jacobsen FF, Kjeken I. A multicenter investigation of reablement in Norway: a clinical controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19(1):29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-019-1038-x.

Lewin G, de San Miguel K, Knuiman M, Alan J, Boldy D, Hendrie D, et al. A randomised controlled trial of the home Independence program, an Australian restorative home-care programme for older adults. Health & Social Care in the Community. 2013;21(1):69–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2012.01088.x.

Tuntland, H., et al., Predictors of outcomes following reablement in community-dwelling older adults. 2017. 12.

Swedish Parliament, Offentlighets- och sekretesslag (2009:400) [public access and secrecy act (2009:400)]. Stockholm: Swedish Parliament.

Vardeberg, K. and T. Barthen. Sunnaas ADL-index. 2001. Retrieved March 4, 2021]; Available from: https://www.sunnaas.no/fag-og-forskning/fagstoff/sunnaas-adl-index.

Korpelainen JT, Niileksela E, Myllyla VV. The Sunnaas index of activities of daily living: responsiveness and concurrent validity in stroke. Scand J Occup Ther. 1997;4(1–4):31–6. https://doi.org/10.3109/11038129709035719.

Wales K, Lannin NA, Clemson L, Cameron ID. Measuring functional ability in hospitalized older adults: a validation study. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40(16):1972–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2017.1323021.

Bathen T, Vardenberg K. Test-retest reliability of the Sunnaas ADL index. Scand J Occup Ther. 2001;8(3):140–7.

Åberg AC, Lindmark B, Lithell H. Development and reliability of the general motor function assessment scale (GMF)--a performance-based measure of function-related dependence, pain and insecurity. Disabil Rehabil. 2003;25(9):462–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/0963828031000069762.

Åberg AC, Lindmark B, Lithell H. Evaluation and application of the general motor function assessment scale in geriatric rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2003;25(7):360–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/0963828031000093468.

Gustafsson U, Grahn B. Validation of the general motor function assessment scale–an instrument for the elderly. Disabil Rehabil. 2008;30(16):1177–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638280701623422.

Euroqol-Group. EQ-5D-5L. 2009. Retrieved March 4, 2021.]; Available from: https://euroqol.org/eq-5d-instruments/eq-5d-5l-about/.

Haywood K, Garratt A, Fitzpatrick R. Quality of life in older people: a structured review of generic self-assessed health instruments. Qual Life Res. 2005;14(7):1651–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-005-1743-0.

Ryburn B, Wells Y, Foreman P. Enabling independence: restorative approaches to home care provision for frail older adults. Health & Social Care in the Community. 2009;17(3):225–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2008.00809.x.

Chi NF, Huang YC, Chiu HY, Chang HJ, Huang HC. Systematic review and meta-analysis of home-based rehabilitation on improving physical function among home-dwelling patients with a stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2020;101(2):359–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2019.10.181.

Donohue K, et al. Home-based multidisciplinary rehabilitation following hip fracture surgery: what is the evidence? Rehabil Res Pract. 2013;2013:875968.

Tessier A, Beaulieu MD, Mcginn CA, Latulippe R. Effectiveness of Reablement: A Systematic Review. Healthcare policy. Politiques de sante. 2016;11(4):49–59.

Sims-Gould J, Tong CE, Wallis-Mayer L, Ashe MC. Reablement, reactivation, rehabilitation and restorative interventions with older adults in receipt of home care: a systematic review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18(8):653–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2016.12.070.

Rasmussen RS, Østergaard A, Kjær P, Skerris A, Skou C, Christoffersen J, et al. Stroke rehabilitation at home before and after discharge reduced disability and improved quality of life: a randomised controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2016;30(3):225–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215515575165.

Doh D, Smith R, Gevers P. Reviewing the reablement approach to caring for older people. Ageing Soc. 2019;40(6):1–13.

Cook RJ, Berg K, Lee KA, Poss JW, Hirdes JP, Stolee P. Rehabilitation in home care is associated with functional improvement and preferred discharge. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94(6):1038–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2012.12.024.

Pettersson C, Iwarsson S. Evidence-based interventions involving occupational therapists are needed in re-ablement for older community-living people: a systematic review. Br J Occup Ther. 2017;80(5):273–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308022617691537.

Hunter EG, Kearney PJ. Occupational therapy interventions to improve performance of instrumental activities of daily living for community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review. Am J Occup Ther. 2018;72(4):9.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable. Open Access funding provided by Jönköping University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AJ, SF and MEB planned the study. AJ, SF, EIF and MEB analyzed and interpreted the data and were major contributors in writing the manuscript. AJ, SF, EIF and MEB contributed in reading and further developing the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study is based on secondary analyses of data from a municipality project. The participants gave informed consent for participating in the municipality project. Analyses of collected data was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (#2019–00706). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

This study contains no individual person’s data.

Competing interests

The first author is employed in the municipality from where data were retrieved. All other authors declare no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Johansson, A., Ernsth Bravell, M., Fransson, E.I. et al. Factors associated to functioning and health in relation to home rehabilitation in Sweden: a non-randomized pre-post intervention study. BMC Geriatr 21, 416 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02360-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02360-1