Abstract

Background

Main pancreatic duct (MPD) dilation is a high-risk stigmata/worrisome feature of malignancy in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs). The threshold of MPD diameter in predicting malignancy may be related to the lesion location. This study aimed to separately identify the thresholds of MPD for malignancy of IPMNs separately for the head-neck and body-tail.

Materials and methods

A total of 185 patients with pathologically confirmed IPMNs were included. Patient demographic information, clinical data, and pathological features were obtained from the medical records. Those IPMNs with high-grade dysplasia or with associated invasive carcinoma were considered as malignant tumor. Radiological data including lesion location, tumor size, diameter of the MPD, mural nodule, and IPMN types (main duct, MD; branch duct, BD; and mixed type, MT), were collected on computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging. Serum carbohydrate antigen 19-9 levels, serum carcinoembryonic antigen levels, and the medical history of diabetes mellitus, chronic cholecystitis, and pancreatitis were also collected.

Results

Malignant IPMNs were detected in 31.6% of 117 patients with lesions in the pancreatic head-neck and 20.9% of 67 patients with lesions in the pancreatic body-tail. In MPD-involved IPMNs, malignancy was observed in 54.1% of patients with lesions in the pancreatic head-neck and 30.8% of patients with lesions in the pancreatic body-tail (p < 0.05). The cutoff value of MPD diameter for malignancy was 6.5 mm for lesions in the head-neck and 7.7 mm for lesions in the body-tail in all type of IPMNs. In MPD-involved IPMNs, the threshold was 8.2 mm for lesion in pancreatic head-neck and 7.7 mm for lesions in the body-tail. Multivariate analysis confirmed that MPD diameter ≥ 6.5 mm (pancreatic head-neck) and MPD diameter ≥ 7.7 mm (pancreatic body-tail) were independent predictors of malignancy (p < 0.05). Similar results were observed in MPD-involved IPMNs using 8.2 mm as a threshold.

Conclusion

The thresholds of the dilated MPD may be associated with IPMNs locations. Thresholds of 6.5 mm for lesions in the head-neck and 7.7 mm for lesions in the body-tail were observed. For MPD-involved IPMNs alone, threshold for lesions in the head-neck was close to that in the body-tail.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs) are mucin-producing cystic tumors with a variable degree of dysplasia and are considered precursors of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. According to the revised Fukuoka consensus guidelines [1], IPMN is subdivided into three types considering the degree of involvement of the pancreatic ductal system: main duct (MD) type, branch duct (BD) type, and mixed type (features of MD and BD, MT). IPMNs with MPD diameters not less than 10 mm, and/or with an enhanced mural nodule ≥ 5 mm are considered as high-risk stigmas and should be resected immediately [1]. In contrast, a diameter of MPD of 5–9 mm, cystic structure not less than 30 mm and an elevated serum carbohydrate antigen (CA) 19-9 level are considered worrisome features, suggesting nonoperative watchful management.

Nevertheless, several studies have challenged the cutoff value of MPD ≥ 10 mm as a high-risk stigma. Abdeljawad et al. [2] considered that a cutoff of 8 mm of MPD was able to discriminate benign from malignant MD-IPMNs. Hackert et al. [3] found that the malignancy risk was 59% in IPMNs with MPD sizes between 5 and 9 mm. Del Chiaro reported that a cutoff of 5 to 7 mm of MPD diameter was the best predictor to discriminate between malignant and benign IPMNs [4]. Roch et al. [5] pointed out that diffuse MPD dilation of IPMNs was an independent predictor of the development of invasive carcinomas. Diffuse dilation reflects diffuse MPD involvement of the tumor or an obstructing tumor located in the pancreatic head. However, they were ambiguous about the exact MPD dilation diameter that predicts the malignancy of IPMNs according to the lesion’s location in the pancreas (head-neck versus body-tail).

Interestingly, a recent study suggested that the threshold for the MPD diameter was different for MPD-involved IPMNs located in the pancreatic head-neck (9.0 mm) and body-tail (7.0 mm) [6]. However, this is the only study so far showing that the anatomic site of the gland should be considered when calculating the threshold. The validity of these results should be confirmed by other studies. Moreover, this study only investigated the MD/MT type of IPMNs. The thresholds are still unclear if BD-IPMNs were also included. Therefore, the aim of this study was to identify the threshold of MPD for identifying malignancy of IPMNs considering the tumor location (head-neck versus body-tail).

Materials and methods

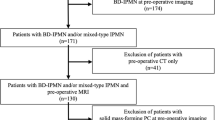

Patients

This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Review Board of the Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine. All procedures in this study adhered to Declaration of Helsinki. This study included 185 patients with pathologically proven IPMNs who underwent surgery during 2011–2021. Any patients with missing data were excluded. Surgery was performed based on Fukuoka guidelines, or because of obvious clinical symptoms and patient’s request. Patient demographic information, clinical data, and pathological features were obtained from the medical records. Fasting plasma glucose levels and 2-h plasma glucose levels were obtained within one week before the operation. Diabetes mellitus (DM) was defined according to the plasma glucose levels and a history of DM. We collected data of preoperative symptoms (such as abdominal symptoms and overt jaundice), serum carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) levels and serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels. Medical histories of chronic cholecystitis and pancreatitis were also collected. Imaging information was obtained from the Picture Archiving and Communication System.

Imaging data

The following radiological data were collected on computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): lesion location (head and neck vs. body and tail), tumor sizes, diameter of the main pancreatic duct (MPD), and mural nodule (enhanced solid component with a size ≥ 5.0 mm). The MPD diameter was measured at the site of the maximal dilation of the pancreatic duct on the Picture Archiving and Communication System. If the lesion was too large, the location was evaluated based on the site of the center of the cyst. If there were multiple lesions, the location was judged based on the main cyst. MD-IPMN was considered when segmental or diffuse involvement of the MPD was observed; BD-IPMN was considered when the lesions communicated with the MPD [7]. MT-IPMN was defined when the lesions had features of both MD- and BD-IPMNs. We combined MD-IPMN and MT-IPMN as MPD-involved IPMNs. The imaging features were reviewed blindly and independently by two radiologists (with extensive experience in pancreatic radiology) with no prior knowledge of the detailed histopathological information of any patients.

Histological examinations

The histological diagnosis of IPMN was based on the World Health Organization guidelines for IPMNs. IPMNs were classified into low-intermediate dysplasia, high-grade dysplasia, and invasive adenocarcinoma. Malignant IPMNs were defined as those with high grade dysplasia or with associated invasive carcinoma. Lymph node metastasis (yes vs. no) and peripancreatic extension (organ invasion and vascular invasion) were also evaluated.

Statistical analysis

The data analyses were performed with SPSS 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous data are shown as the mean ± standard deviation and qualitative data are shown as numbers (percentage). Continuous data, such as patient age, tumor size, the serum levels of CEA and CA19-9, and MPD diameter were evaluated by independent-sample t tests or Mann–Whitney U tests. Qualitative data, such as sex, dysplasia level, tumor type, tumor location, chronic cholecystitis, pancreatitis, abdominal symptoms, lymph node metastasis, peripancreatic extension, and mural nodules, were subsequently compared by the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. A receiver operating curve was used to calculate the threshold of MPD in identifying malignant IPMNs. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses were used to evaluate the association of MPD with invasive carcinoma and malignant IPMNs. Logistic regression analyses were also performed to show the association of MPD with invasive carcinoma and malignant IPMNs in MPD-involved IPMNs. P values less than 0.05 were considered as statistically significant. The interobserver agreements were calculated using the weighted kappa values as follows: 0.00–0.20, poor agreement; 0.21–0.40, fair agreement; 0.41–0.60, moderate agreement; 0.61–0.80, good agreement; and 0.81–1.00, excellent agreement.

Results

Clinicopathological features of IPMNs

In our study, a total of 185 patients were included and their clinical data are shown in Table 1. There were 134 patients who had low-intermediate grade neoplasms and 51 patients who had tumors with high-grade or carcinoma. Low-intermediate grade IPMNs were more commonly seen in BD patients, while high-grade IPMNs and carcinoma were more commonly seen in patients with main type or/and mixed type IPMNs (p < 0.01). In addition, significant differences were found in serum CEA and CA19-9 levels (p < 0.01) between these two groups. Patients with malignant IPMNs had larger size of MPD diameters and mural nodules (p < 0.001). Extrapancreatic extensions were only seen in malignant IPMNs (p < 0.001). DM were more common seen in patients with malignant IPMNs than in those with low-intermediate grade IPMNs. However, no significant differences were found in patient age, sex, tumor size, tumor location, pancreatitis, abdominal symptoms or lymph node metastasis between the patients with and without malignant IPMNs.

Clinicopathological features of MPD-involved type IPMNs

Next, we analyzed the clinicopathological features of MPD-involved IPMNs with and without malignant characteristics (Table 2). No significant differences were found for age, sex, tumor size, serum CEA level, serum CA19-9 level, lymph node metastasis, abdominal symptoms or complications between patients with low-intermediate grade IPMNs and high-grade/invasive carcinomas. In contrast, in patients with MPD-involved IPMNs, more than half of patients (54.1%) with IPMNs in the pancreatic head and neck had malignant tumors, which was significantly higher than that in patients with IPMNs in the pancreatic body and tail (30.8%) (p < 0.05). A larger MPD diameter, the presence of mural nodules and DM, and extrapancreatic extension were more common seen in high-grade IPMNs/invasive carcinomas than in low-intermediate grade IPMNs (p < 0.05).

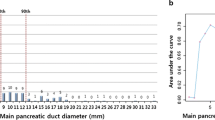

Threshold of MPD in identifying malignancy in IPMNs of head-neck/body-tail

By analyzing the association between MPD diameter and the malignancy of IPMNs, we found that the cutoff value of the MPD diameter to distinguish benign from malignant IPMNs was 6.5 mm for head-neck IPMNs (area under the curve (AUC) = 0.82, sensitivity = 0.73, specificity = 0.82) and was 7.7 mm for body-tail IPMNs (AUC = 0.61, sensitivity = 0.43, specificity = 0.87), respectively (Fig. 1).

Univariable and multivariable logistic regression were used to show the association of the calculated threshold of MPD with malignant IPMNs (Tables 3 and 4). An MPD not less than 6.5 mm was associated with a higher risk of malignant IPMNs in univariate analysis (odds ratio (OR), 12.73; 95% CI 5.04–32.16, p < 0.001) and multivariate analysis (OR, 14.14; 95% CI 4.61–43.39, p < 0.001) for IPMNs at pancreatic head and neck (Table 3). For body-tail IPMNs (Table 4), MPD not less than 7.7 mm was an independent predictor of malignancy on univariate analysis (OR, 4.93; 95% CI 1.31–18.52, p = 0.018) and multivariate analysis (OR, 9.83; 95% CI 1.39–69.57, p = 0.022). CA19-9 levels not lower than 37 U/mL were also identified as predictors of malignancy for IPMNs of the head-neck (Table 3) and body-tail (Table 4) of the pancreas. The presence of mural nodules was associated with malignancy for IPMNs of the body-tail of the pancreas (Table 4). An MPD diameter of 6.5 mm was shown to have fair agreement (kappa = 0.52) with the pathological results in identifying malignancy.

Threshold of MPD in identifying malignancy in MPD-involved IPMNs of the pancreatic head-neck/body-tail

The best cutoff value of MPD diameter to distinguish between malignant and benign MPD-involved IPMNs with was 8.2 mm for head-neck IPMNs (AUC = 0.70, sensitivity = 0.64, specificity = 0.78) and was 7.7 mm for body-tail IPMNs (AUC = 0.68, sensitivity = 0.75, specificity = 0.61), respectively (Fig. 2). Subsequently, we evaluated the association between calculated threshold of MPD and malignant IPMNs in patients with MPD-involved IPMNs (Table 5). For head and neck IPMNs, an MPD diameter larger than 8.2 mm was associated with a higher risk of malignant IPMNs (OR = 9.75; 95%CI, 2.15–44.07). However, no significant correlation was observed between the calculated threshold and malignancy of IPMNs in pancreatic body and tail (p = 0.07) (Table 6). An MPD diameter of 8.2 mm was shown to have fair agreement (kappa = 0.42) with the pathological results in identifying head-neck malignancy. If using 6.5 mm as a threshold for malignancy in MPD-involved IPMNs located at head-neck, the kappa value was 0.31.

Threshold of MPD in identifying malignancy in BD-IPMNs of the pancreatic head-neck//body-tail

The best cutoff value of MPD diameter to distinguish between malignant and benign BD-IPMNs was 2.9 mm for head-neck IPMNs (AUC = 0.66, sensitivity = 1.00, specificity = 0.38) (Additional file 1: Fig. S1A) and 3.1 mm for body-tail IPMNs (AUC = 0.64, sensitivity = 0.32, specificity = 1.00) (Additional file 1: Fig. S1B).

Discussion

It is well-known that dilation of MPD is associated with malignancy in IPMNs. For IPMNs with MPD diameter ≥ 10 mm, surgery is recommended to prevent any possible progression to pancreatic cancer. However, a few studies have indicated that the threshold should be lower than 10 mm [8, 9]. Moreover, a study reported that the threshold was related to the tumor location for MD/MT IPMNs. Our present data also demonstrated that the threshold of MPD diameter was lower than 10 mm for identifying malignant IPMNs, 6.5 mm for lesions in pancreatic head-neck and 7.7 mm for lesions in body-tail. Our data also supported that the threshold of MPD diameter in identifying malignant MPD-involved IPMNs of pancreatic head-neck should be set at 8.0–9.0 mm.

Crippa et al. [6] stressed that MPD diameters for malignancy are different in MPD-involved IPMNs of the pancreatic head and body-tail. According to their study, surgery was recommended for MPD-involved IPMNs with MPD ≥ 9 mm in the pancreatic head and for IPMNs with MPD ≥ 7 mm in the pancreatic body-tail, respectively. In addition, for IPMNs with MPD < 8 mm in the head and MPD > 6 mm in the body-tail with high-risk stigma, immediate surgical resection was also suggested. However, this solitary research required validation by other studies. Moreover, BD-IPMNs were not included in that study. Our results showed that main-duct involved IPMNs with MPD ≥ 8.2 mm in the pancreatic head and with MPD ≥ 7.7 mm in the pancreatic body-tail were associated with malignancy of IPMNs, respectively. Our results were close to those reported by Crippa et al. Moreover, we also calculated the threshold of the MPD diameter for all types of IPMNs. The cutoff values of MPD diameter were 6.5 mm and 7.7 mm for malignancy of IPMNs in the pancreatic head-neck and body-tail, respectively. Our results showed that the threshold of the MPD diameter for distinguishing malignancy in the pancreatic head and neck was smaller than that reported by Crippa et al. They analyzed the size of the MPD diameter of MPD-involved IPMNs, but they did not consider BD-IPMNs. We took BD-IPMNs into account because the lesions located in the branch duct might communicate with the MPD and their aggressive behavior could influence the dilation of the MPD. Yoshioka et al. [10] showed that BD-IPMNs with MPD diameter more than 3 mm and a DM history had a higher risk of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Our data showed similar thresholds both in head-neck and body tail IPMNs. Interestingly, a recent study indicated that a cutoff of 5 to 7 mm MPD diameter was the best predictor to discriminate between malignant and benign IPMNs [4]. Ateeb et al. also indicated that main pancreatic duct dilation greater than 6 mm is associated with an increased risk of malignancy [11]. Our threshold of 6.5 mm is consistent with these findings. Moreover, the results of our study and those of Crippa et al. both supported that the threshold should be set at 7–8 mm for IPMNs located in the body-tail.

In addition, our data also showed that a higher risk of malignancy was found in IPMNs located in the pancreatic head and neck than those located in the pancreatic body and tail which consistent with the results of other studies. Kerlakian et al. [12] showed that lesions of the pancreatic head and uncinate were more likely to harbor malignancy than lesions of the body and tail. Jones et al. [13] indicated that IPMNs located in pancreatic head were associated with malignancy in univariate analysis. Suzuki et al. [14] pointed out that a tumor location in the pancreatic head was one of the predictive factors for malignant IPMNs. However, the reason was unclear just like the pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma occurs more frequently in the pancreatic head. IPMNs located in the pancreatic head and neck might already have aggressive behaviors and be resected before a significant dilation of the MPD occurs.

In addition to the dilation of the MPD diameter, tumor size > 30 mm and CA19-9 level ≥ 37 U/mL were also found to be risk factors for malignancy of IPMNs in the pancreatic head and neck in the present study. Ciprani et al. [15] indicated that 63% of IPMN patients with a CA19-9 higher than 37U/mL were associated with malignancy and a poor prognosis. IPMNs located in the head and neck of the pancreas with these risk factors should be given more attention and surgical resection should be considered instead of surveillance. However, further study is needed to evaluate the association between these risk factors and malignant IPMNs in the pancreatic body and tail.

Hirono et al. [16] showed that IPMNs with lesions located in the pancreatic body/tail had a higher risk of recurrence in the remnant pancreas after surgery. They explained this phenomenon by neoplastic cells being transferred downstream through the flow of pancreatic juice to implant in the pancreatic duct epithelium. Lesions implanted in the pancreatic duct eventually led to dilation of the MPD. This finding might explain the difference in the MPD diameter in the pancreatic head-neck and body-tail in our study. Huang et al. [17] also stressed that being located in the pancreatic body/tail was an independent prognostic factor related to distant metastases of IPMNs. They illustrated that cancer-specific survival was shorter for head lesions than for body/tail lesions, which possibly contributed to a tumor progression.

In addition, MT-IPMNs in main-duct involved IPMNs in our study were more common seen than MD-IPMNs. This difference in tumor types might lead to a smaller MPD diameter in the present study. Some MT-IPMNs may have only minimal involvement of the MPD and no MPD dilation [18]. Therefore, the size of the MPD to discriminate benign and malignant IPMNs in MPD involved IPMNs in our study (8.2 mm) was slightly smaller than that in the previous study (9 mm).

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and EUS-guided the needle biopsy are useful in the management and diagnosis of pancreatic solid [19] or cystic lesions [20,21,22]. Li et al. [23] reported that EUS with or without fine-needle aspiration had better performance in diagnosing pancreatic cystic neoplasms (PCNs) than CT or MRI. EUS also showed slight better performance in characterizing internal structures, such as septa and mural nodules [23]. A recent meta-analysis further showed that contrast-enhanced EUS (CE-EUS) had good ability for the characterization of mural nodules within PCNs [24]. However, EUS is not routinely performed for pancreatic diseases in our institution. Therefore, the imaging evaluations in our study were mainly based on the CT or MRI.

There are several limitations of our study. First, the number of MD-IPMNs was relatively small, and larger data sets are needed for a further study. Second, our study was a single-institution retrospective study which may cause selection bias, and a multicenter study should be performed to test our findings. Third, as a retrospective study, we did not evaluate the association between MPD diameter and survival or recurrence after surgery and a prospective study is necessary in the future. Fourth, the IPMN patients who did not undergo surgical resection were not included in our analysis, such as those who underwent surveillance. The loss of these populations may affect the results. Nevertheless, surgery may be performed for 40% of patients without "worser" features as their request or having clinical symptoms in our study. These subjects were complementary to the patients who underwent surveillance. Therefore, our results may also be generalizable for identifying malignancy in all IPMNs.

In conclusion, our study shows a slight difference in MPD thresholds for malignancy between IPMNs of the pancreatic head and body-tail in the MD/MT type. Moreover, a lower MPD threshold (6.5 mm) was observed for malignant IPMNs of the pancreatic head-neck for all types of IPMNs. For MPD-involved IPMNs alone, threshold for lesions in the head-neck was close to that in the body-tail (8.2 mm and 7.7 mm). Further investigations that focused on the association between MPD diameter and tumor location are needed to show the role of the MPD diameter in predicting the malignancy of IPMNs more accurately.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its Additional file 1).

References

Tanaka M, Fernández-Del Castillo C, Kamisawa T, Jang JY, Levy P, Ohtsuka T, et al. Revisions of international consensus Fukuoka guidelines for the management of IPMN of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2017;17(5):738–53.

Abdeljawad K, Vemulapalli KC, Schmidt CM, Dewitt J, Sherman S, Imperiale TF, et al. Prevalence of malignancy in patients with pure main duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79(4):623–9.

Hackert T, Fritz S, Klauss M, Bergmann F, Hinz U, Strobel O, et al. Main-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm: high cancer risk in duct diameter of 5 to 9 mm. Ann Surg. 2015;262(5):875–80.

Del Chiaro M, Beckman R, Ateeb Z, Orsini N, Rezaee N, Manos L, et al. Main duct dilatation is the best predictor of high-grade dysplasia or invasion in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. Ann Surg. 2020;272(6):1118–24.

Roch AM, Ceppa EP, Al-Haddad MA, DeWitt JM, House MG, Zyromski NJ, et al. The natural history of main duct-involved, mixed-type intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm: parameters predictive of progression. Ann Surg. 2014;260(4):680–8.

Sugimoto M, Elliott IA, Nguyen AH, Kim S, Muthusamy VR, Watson R, et al. Assessment of a revised management Strategy for patients with intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms involving the main pancreatic duct. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(1):e163349.

Kang MJ, Jang JY, Lee S, Park T, Lee SY, Kim SW. Clinicopathological meaning of size of main-duct dilatation in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of pancreas: proposal of a simplified morphological classification based on the investigation on the size of main pancreatic duct. World J Surg. 2015;39(8):2006–13.

Crippa S, Aleotti F, Longo E, Belfiori G, Partelli S, Tamburrino D, et al. Main duct thresholds for malignancy are different in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreatic head and body-tail. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(2):390-399.e7.

Das KK, Mullady DK. Main pancreatic duct dilation in IPMN: When (and Where) to Get “Worried”? Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(2):272–5.

Yoshioka T, Shigekawa M, Ikezawa K, Tamura T, Sato K, Urabe M, et al. Risk factors for pancreatic cancer and the necessity of long-term surveillance in patients with pancreatic cystic lesions. Pancreas. 2020;49(4):552–60.

Ateeb Z, Valente R, Pozzi-Mucelli RM, Malgerud L, Schlieper Y, Rangelova E, et al. Main pancreatic duct dilation greater than 6 mm is associated with an increased risk of high-grade dysplasia and cancer in IPMN patients. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2019;404(1):31–7.

Kerlakian S, Dhar VK, Abbott DE, Kooby DA, Merchant NB, Kim HJ, et al. Cyst location and presence of high grade dysplasia or invasive cancer in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: a seven institution study from the central pancreas consortium. HPB (Oxford). 2019;21(4):482–8.

Jones NB, Hatzaras I, George N, Muscarella P, Ellison EC, Melvin WS, et al. Clinical factors predictive of malignant and premalignant cystic neoplasms of the pancreas: a single institution experience. HPB (Oxford). 2009;11(8):664–70.

Suzuki Y, Nakazato T, Yokoyama M, Kogure M, Matsuki R, Abe N, et al. Development and potential utility of a new scoring formula for prediction of malignant intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas. Pancreas. 2016;45(9):1227–32.

Ciprani D, Morales-Oyarvide V, Qadan M, Hank T, Weniger M, Harrison JM, et al. An elevated CA 19–9 is associated with invasive cancer and worse survival in IPMN. Pancreatology. 2020;20(4):729–35.

Hirono S, Shimizu Y, Ohtsuka T, Kin T, Hara K, Kanno A, et al. Recurrence patterns after surgical resection of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) of the pancreas; a multicenter, retrospective study of 1074 IPMN patients by the Japan Pancreas Society. J Gastroenterol. 2020;55(1):86–99.

Huang X, You S, Ding G, Liu X, Wang J, Gao Y, et al. Sites of distant metastases and cancer-specific survival in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm with associated invasive carcinoma: a study of 1,178 patients. Front Oncol. 2021;11:681961.

Sahora K, Fernández-del Castillo C, Dong F, Marchegiani G, Thayer SP, Ferrone CR, et al. Not all mixed-type intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms behave like main-duct lesions: implications of minimal involvement of the main pancreatic duct. Surgery. 2014;156(3):611–21.

Gkolfakis P, Crinò SF, Tziatzios G, Ramai D, Papaefthymiou A, Papanikolaou IS, et al. Comparative diagnostic performance of end-cutting fine-needle biopsy needles for EUS tissue sampling of solid pancreatic masses: a network meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2022;95(6):1067-1077.e15.

Facciorusso A, Kovacevic B, Yang D, Vilas-Boas F, Martínez-Moreno B, Stigliano S, Rizzatti G, Sacco M, Arevalo-Mora M, Villarreal-Sanchez L, et al. Predictors of adverse events after endoscopic ultrasound-guided through-the-needle biopsy of pancreatic cysts: a recursive partitioning analysis. Endoscopy. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1831-5385.

Facciorusso A, Del Prete V, Antonino M, Buccino VR, Wani S. Diagnostic yield of EUS-guided through-the-needle biopsy in pancreatic cysts: a meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;92(1):1-8.e3.

Faias S, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound with fine needle aspiration is useful in pancreatic cysts smaller than 3 cm. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-020-01565-9.

Lu X, Zhang S, Ma C, Peng C, Lv Y, Zou X. The diagnostic value of EUS in pancreatic cystic neoplasms compared with CT and MRI. Endosc Ultrasound. 2015;4(4):324–9.

Lisotti A, Napoleon B, Facciorusso A, Cominardi A, Crinò SF, Brighi N, Gincul R, Kitano M, Yamashita Y, Marchegiani G, Fusaroli P. Contrast-enhanced EUS for the characterization of mural nodules within pancreatic cystic neoplasms: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;94(5):881-889.e5.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was funded by Medical development and Medical Assistance Foundation of Jiangsu Province Hospital of Chinese Medicine and National Natural Science Foundation of China (81773460).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HZ: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing—review and editing. XL: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing—review and editing. YW: Formal analysis, review and editing. ZW: Formal analysis, review and editing. JZ: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Writing—review and editing. ZW: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—review and editing; XC: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—review and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Board of the the Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine (No. 2017NL-137-05).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Informed consent

Informed consent was waived by the Ethics Board of the the Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine. During the study, Declaration of Helsinki was adhered to.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Fig. S1

. Receiver operating curve to calculate the threshold of main pancreatic duct (MPD) in identifying malignancy in branch-duct (BD)-intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs). The threshold was 2.9 mm for lesions at head-neck (A) and was 3.1 mm for lesions at body-tail (B).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, H., Li, X., Wang, Y. et al. Threshold of main pancreatic duct for malignancy in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm at head-neck and body-tail. BMC Gastroenterol 22, 473 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-022-02577-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-022-02577-3