Abstract

Background

Persons with diabetes have 27% elevated risk of developing colorectal cancer (CRC) and are disproportionately from priority health disparities populations. Federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) struggle to implement CRC screening programs for average risk patients. Strategies to effectively prioritize and optimize CRC screening for patients with diabetes in the primary care safety-net are needed.

Methods

Guided by the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation and Sustainment Framework, we conducted a stakeholder-engaged process to identify multi-level change objectives for implementing optimized CRC screening for patients with diabetes in FQHCs. To identify change objectives, an implementation planning group of stakeholders from FQHCs, safety-net screening programs, and policy implementers were assembled and met over a 7-month period. Depth interviews (n = 18–20) with key implementation actors were conducted to identify and refine the materials, methods and strategies needed to support an implementation plan across different FQHC contexts. The planning group endorsed the following multi-component implementation strategies: identifying clinic champions, development/distribution of patient educational materials, developing and implementing quality monitoring systems, and convening clinical meetings. To support clinic champions during the initial implementation phase, two learning collaboratives and bi-weekly virtual facilitation will be provided. In single group, hybrid type 2 effectiveness-implementation trial, we will implement and evaluate these strategies in a in six safety net clinics (n = 30 patients with diabetes per site). The primary clinical outcomes are: (1) clinic-level colonoscopy uptake and (2) overall CRC screening rates for patients with diabetes assessed at baseline and 12-months post-implementation. Implementation outcomes include provider and staff fidelity to the implementation plan, patient acceptability, and feasibility will be assessed at baseline and 12-months post-implementation.

Discussion

Study findings are poised to inform development of evidence-based implementation strategies to be tested for scalability and sustainability in a future hybrid 2 effectiveness-implementation clinical trial. The research protocol can be adapted as a model to investigate the development of targeted cancer prevention strategies in additional chronically ill priority populations.

Trial registration

This study was registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT05785780) on March 27, 2023 (last updated October 21, 2023).

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

Patients with diabetes mellitus have an estimated 27% elevated lifetime risk of developing colorectal cancer (CRC), and are disproportionately from priority health disparities populations (e.g., low-income, Non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic) [1, 2]. Nationally, guideline concordant receipt of CRC screening for patients with diabetes is not significantly different for women with diabetes (57% vs. patients without diabetes 58%) and is significantly higher among men with diabetes (63% vs. patients with diabetes 58%) [3]. CRC screening for patients with diabetes, who do not have other indications of high risk (e.g., family history of CRC, polyp removal during colonoscopy, personal history of CRC, inflammatory bowel disease) are advised to follow the average risk screening recommendations [4]. Federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) primarily serve as primary care for priority health disparities populations and struggle to sustainably implement CRC screening programs for average-risk patients which includes patients with diabetes. CRC screening uptake in FQHCs populations has been consistently lower (44.1%) than the national average for average risk, age-eligible adults (67.3%) [5].

Persons receiving diabetes care in FQHCs have elevated health risks overall and higher rates of poverty and low-income status than the general population [6]. Ten percent of FQHC patients have a diabetes diagnosis and more than a third within this group have uncontrolled diabetes (HbA1c > 9%). Failure to implement preventive CRC screenings translates to an average of 6.5 years of lost life for patients subsequently diagnosed with CRC [7]. Moreover, this contributes to greater burden for patients with diabetes who are diagnosed with CRC who suffer greater morbidity, all-cause mortality, and cancer-specific mortality compared to CRC patients [8,9,10]. Therefore, efforts to prioritize CRC screening for patients with diabetes are needed in primary care safety-net settings.

Multiple evidence-based CRC screening tests are available which complicates implementation. The U.S. Preventive Services Taskforce (USPSTF) recommends CRC screening in adults aged 45–75, with multiple screening options available including non-invasive stool based testing: high sensitivity guaiac fecal occult blood tests (gFOBT), fecal immunochemical test (FIT), FIT plus stool DNA testing (FIT-DNA); and direct visualization tests: colonoscopy, computed tomography (CT) colography, and flexible sigmoidoscopy (FS) (with or without FIT) (see Table 1 for intervals) [4]. Colonoscopy and FS, have been shown to reduce mortality by (68% and 28%, respectively). FIT and FOBT are associated with 13–33% mortality reductions. Stool-based testing mortality reductions require sustained annual adherence. [11,12,13,14]. Research has shown that failures to screen at all, to screen at appropriate intervals, and to follow-up on abnormal results are associated with risk of CRC death [15].

Given major differences in mortality reduction benefits, temporal intervals for retesting, costs, and patient burden, controversies have emerged surrounding the pros and cons of testing methods [16, 17]. Colonoscopy and FS allow for polypectomies, which can prevent CRC [18, 19]; however, FS is not widely used in the U.S, because colonoscopy evaluates the entire colon, can be done every 10 years, and is associated with a greater mortality reduction [20]. A re-analysis of the USPSTF data suggest that prevention, through the removal of polyps during colonoscopy, is the sole mechanism of CRC mortality reductions [19]. Colonoscopy is thus the “gold standard,” despite critiques about the rigor of this evidence (e.g., indirect and observational). [21,22,23,24]. In FQHCs, non-invasive tests are emphasized and colonoscopies are often a second line-screening based on abnormal gFOBT/FIT findings. [25]. Non-invasive tests are emphasized because these are less costly, require less time (and time off of work), less complicated to complete, do not require transportation, and are guideline concordant [26]. Despite stool based testing’s acceptability, US-based trials in FQHCs designed to increase annual adherence to stool-based testing have reported low screening adherence over three years (10.4–16.4%) [27,28,29].

Prioritizing colonoscopy with longer testing intervals in under-resourced FQHCs for patients with diabetes introduces fewer opportunities for care breakdowns, is guideline concordant, and prevents CRC by removing premalignant colonic polyps. Guided by the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation and Sustainment [30]. (EPIS) framework, this research study will develop and evaluate targeted CRCs screening strategies for patients with diabetes in safety-net settings. This study addresses known implementation challenges using a “designing for dissemination” approach [31,32,33] that attends to important contextual, organizational capacity and patient complexity factors that impact CRC screening program implementation in clinics and uptake among patients with diabetes.

Conceptual framework

The design of this study was guided by the EPIS framework. EPIS is an evidence-based practice (EBP) implementation framework that includes four defined phases for assessment of inner and outer contextual factors that influence EBP implementation (see Table 2). For this study, the EBP is CRC screening uptake among age eligible patients with diabetes. Exploration is the act of identifying patient needs and the availability of EBPs to address identified needs, and the decision to adopt evidence into practice based on fit within the inner clinical context. During this phase, the adaptations to the evidence are based on system, organization, and individual patient factors. Preparation includes planning implementation, inventorying proposed challenges, and developing strategies to overcome anticipated barriers. A critical component of this phase is the planning of implementation strategies to support EBP utilization in the next two phases and to address organizational climate to ensure that EBPs will be supported, expected, and rewarded. During the clinical trial, this study focuses on implementation, the process of assuring and balancing fidelity to the EBP delivered with adaptations needed to assure program success. Sustainment focuses on maintenance and program and factors impacting implementation over the long haul. EPIS considers innovation factors, which are the characteristics of the EBP being implemented. The innovation-EBP fit considers if the EBP fits the patient, provider, and organizational needs. Innovation factors are assessed and can be adapted to maximize the fit of an EBP while maintaining the core elements of the intervention to retain fidelity.

Methods and design

Identifying multi-level change levers: a multi-method stakeholder informed approach

Earlier phases of this research focused on the Exploration and Preparation phases, while the current protocol describes the intervention implementation and its evaluation. During the exploration phase, a secondary analysis was conducted of a nationally representative data set to identify patient level determinants of CRC screening uptake overall (i.e., with any test) and test-specific uptake among individuals with diabetes. We explored disparities in uptake overall and testing type based on race, ethnicity, income, and educational status. Additionally, a scoping literature review was performed to identify evidence-based interventions and implementation strategies for CRC screening and diabetes management in FQHCs. Based on this scoping review, we identified additional interventions and implementation strategies, using the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) taxonomy [34]. A list of interventions and implementation strategies was compiled related to diabetes management processes to expand an existing measure that was developed and used to evaluate the use of evidence-based intervention and implementation for CRC in FQHCs [35].

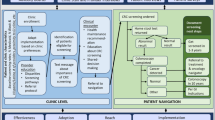

For the preparation phase of the formative research, we used implementation mapping, an iterative process that incorporates community based participatory research principles [36, 37]. An Implementation Planning Group (IPG) was assembled to represent a diversity of implementation actors (e.g., clinicians, state-level decision makers, screening safety-net programs) who work in and with FQHCs. The goal of the IPG, which met 5 times over a six-month period, was to develop shared understandings of the research problem based on empirical knowledge from the national survey analysis, the scoping review of the literature, and local knowledge of the IPG members about patient population and clinic system capacities. The IPG group identified and prioritized the selection of implementation strategies to improve CRC screening uptake for patients with diabetes. The IPG and research team iterated an implementation plan specifying multi-level change objectives and implementation determinants to develop supports to help prioritize CRC screening implementation for patients with diabetes.

Guided by the insights of the exploration and preparation phases, we developed the Strategic Use of Resources for Enhanced ColoRectal Cancer Screening in Patients with Diabetes (SURE: CRC4D) implementation toolkit, which includes tailorable materials and protocols that will be tested in a single arm, hybrid type 2 effectiveness-implementation single arm clinical trial. The objectives of this trial are to:

-

1)

Determine the effectiveness of the SURE: CRC4D multi-component implementation strategies to increase CRC screening uptake among patients with diabetes.

-

2)

Evaluate the fidelity, feasibility, and acceptability of SURE: CRC4D implementation.

-

3)

Refine the SURE: CRC4D toolkit based on multi-level user feedback and conduct an evaluation to promote scalability and sustainable use.

Methods

Study participants and setting

This single arm trial will be conducted in six FQHC clinical sites in New Jersey. Eligibility criteria for the FQHC clinics include: (1) provide care to at least 450 patients aged 50–74 years; (2) 10% of patient population previously diagnosed with diabetes; (3) located in New Jersey; and, 3) clinical and administrative leadership willing to engage in the intervention and research requirements (interviews, data validation, process evaluation). Implementation outcomes will be assessed using mixed methods guided by the EPIS constructs (see Table 2). The methods of this study have been reported using Standard Protocol Items: Recommendation for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) guidelines (Supplemental file 1).

During the implementation a clinic-based registry of patients eligible for CRC screening will be developed for each clinic at baseline and updated at six and 12 months post-baseline. Patient eligibility criteria will include: (1) patients not up-to-date or due for CRC screening [4]. based on electronic health record (EHR) documentation (e.g. FOBT/FIT test in last year, flexible sigmoidoscopy within 4 years, or colonoscopy within 9 years), (2) previous diagnosis of type II diabetes, (3) age-eligible for CRC screening (45–74 years of age) and (4) ) FIT/FOBT that has been ordered for more than 6 months that has not been completed or a sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy referral that has not been completed for 12 or more months. Patients are excluded if they have EHR documentation medical conditions not concordant with standard CRC screening intervals (e.g. prior CRC diagnosis, inflammatory bowel disease, renal failure, etc.) [4].

The NJ Primary Care Research Network (NJPCRN) will recruit eligible clinics for participation. The NJPCRN is an Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality recognized practice-based research in primary care practices. The NJPRN will contact FQHCs that participated in previous research and ask IPG members to make introductions with their FQHC leadership networks. Emails with study flyers will be sent to the FQHC with follow-up telephone outreach. This protocol has been approved by the Rutgers University Institutional Review Board (Pro2020002075). All study participants will be asked to provide informed consent prior to participation in all phase of this research. We expect the distribution of patient participants to reflect the racial/ethnic diversity of the FQHCs recruited, who predominantly serve low-income, racial, and ethnic minority populations.

Implementation strategies

The goal of SURE: CRC4D is to enable FQHC clinics to adopt strategies to optimize the use of evidence based colorectal cancer screenings (See Table 1) uptake for patients with type II diabetes. To accomplish this, multi-level, multi-component implementation strategies (see Table 3) will be utilized. The core components of this implementation effort includes the identification and engagement of 2–3 clinic change champions, who will participate in two virtual learning collaborative events [38,39,40,41] and lead the change effort in the clinic aided by bi-weekly virtual practice facilitator support [38, 42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49]. The SURE: CRC4D toolkit will include guidance on pulling data to develop and implement quality monitoring systems to provide regular audit/feedback to the clinic, patient educational materials in English and Spanish and dissemination materials for clinical meetings to orient other clinic members to the change process being implemented to optimize CRC screening for patients with diabetes [50, 51]. Clinic champions will tailor toolkit resources as clinics may have different electronic medical records, type and composition of staff, clinical workflows, and standing clinical team meetings.

The implementation will be rolled out over a 12-week period. Initially, clinics will be asked to identify 1–3 clinic champions, with at least one clinician (i.e., physician, advanced practice nurse, physician assistant) per team. Each team will meet with the external practice change facilitator approximately two weeks prior to the initial learning collaborative. This initial facilitation meeting is introductory, with the goal of encouraging clinic champions to reflect about the current clinic CRC screening strategies and diabetes care management processes prior to the 1st virtual learning collaborative. Clinical champions will attend the 1- hour virtual learning collaborative, where the materials in the SURE: CRC4D toolkit will be provided and reviewed, and each clinic team will formulate practice change goals. Teams will decide on how to deploy the toolkit strategies at their FQHC sites over the course of the next ten weeks. The practice facilitator will support the clinic champion team in the development, implementation, and refinement of the local practice change plan. The champions will meet with the practice facilitator every two weeks for 8 weeks (4 times). During this time, the plan will be refined and adjusted based on feedback from clinic leaders and practice staff members and identified strengths and barriers that are encountered during the implementation effort. At week 10, a second learning collaborative will be virtually convened, providing a forum where the different clinic teams can share their successes and obstacles during the development and execution of their plan. This forum will foster cross-team learning and idea generation that can inform the refinement of the SURE: CRC4D toolkit and sustainability of practice change efforts. Two weeks after the second learning collaborative, a final virtual facilitation meeting will be held to reflect and refine the practice plan to support sustainability.

Evaluation of the effectiveness and implementation of SURE: CRC4D

The effectiveness and implementation of SURE: CRC4D will be evaluated using a mixed method learning evaluation strategy, where ongoing data collection and analysis are used to refine implementation to optimize adoption of CRC screening for patients with diabetes [52, 53]. This evaluation is designed to address two research questions: (1) are the adapted implementation strategies clinically effective in increasing CRC screening rates for patients with diabetes; and, (2) are the implementation strategies feasible and acceptable to implementers (e.g., clinicians and staff) and patients in FQHCs? This evaluation builds an evidence base about the effectiveness of the implementation strategies in a real-world context and allows for the collection of data that can be used to refine the implementation toolkit for a larger scale, definitive cluster randomized controlled trial. Guided by EPIS, contextual factors were selected based on suggestions from clinical stakeholders, community partners, and previous literature suggesting they may influence implementation success [54,55,56] (see Table 4). The following assessments and measures will be collected to evaluate the trial:

Organizational assessments

Guided by EPIS, contextual factors will be evaluated at baseline and 1 year-post implementation. Medical Directors or the Chief Operating Officer of each clinic will be asked to complete a web-based survey called the Clinic Organizational Information Form (COIF). This survey assesses Implementation Climate and History of Implementation related to CRC screening and diabetes management [35]. Additionally, patient demographics, management strategies, and payor mix are collected using this survey for each clinic.

Clinic staff measures and assessments

The Clinic Staff Questionnaire (CSQ) will be administered to all practice clinicians and staff members at baseline and 12-month post-implementation. The clinic team measures include Medical Provider and Staff Background and history with the organization. Additionally, Change Process Capability will be measured, specifically “previous history of change,” and “ability to initiate and sustain change.” [57]. These two measures have been identified these as key mechanisms for successful organizational change and its wide use in cardiovascular care implementation [58,59,60]. Additional practice-based measures will include: Adaptive Reserve a feature of resilient organizations shown to be associated with practice-level implementation of CRC screening, will be measured in the CSQ with the validated 23-item scale [57, 61]. The CSQ will also include the Implementation Leadership Scale (ILS), a brief psychometrically strong measure that contains 12-items with four subscales of proactive, knowledgeable, supportive, and perseverant leadership [62].

Process data outcomes

Learning collaborative and facilitation phone calls will be audio recorded and transcribed to document issues that arose during the implementation process. Additionally, qualitative interviews will be conducted at baseline and beginning at 6 months post implementation. We will select key implementers (3–4 individuals per site) to assess perceptions of organizational readiness to change, leadership style and additional facility characteristics (e.g., assets and deficits of location, satisfaction with ease of access to facility, etc.). Staff and clinician perceptions of the SURE: CRC4D implementations’ feasibility and acceptability will also assessed asking providers and staff to describe their implementation experiences. The interviews will probe stakeholder perceptions of change in their organizations, systems, and factors that they think impacted implementation. Staff or provider fidelity will be assessed based on the clinic-level proportion of eligible patients who were (1) contacted based on implementation protocol and (2) completed any CRC screening at 1 year.

Patient level: clinical effectiveness outcome and implementation assessment

The primary outcome variables to assess clinical effectiveness will be the clinic level proportion of patients with diabetes who: (a) receive any CRC screening and (b) complete a colonoscopy at 12 months from baseline. An exploratory analysis will assess clinic-level CRC screening completion by glucose control (controlled vs. uncontrolled, i.e., HbA1c > 9 at 12 months). Patient level data is collected in aggregate and will include no identified personal health information.

Patient acceptability will be assessed through the assessment of patient rates of opting-out and non-adherence of CRC screening. This rate will be based on the proportion of CRC screening among patients with diabetes compared to overall eligible patient population (without diabetes) in each clinic.

Data analyses

Qualitative analysis

On a quarterly basis, we will analyze data from each clinic site using a comparative case analysis [63]. Organizational level data and interview transcripts will be organized, read and coded in ATLAS.ti. Data will be analyzed on an ongoing basis, and a working summary of emergent findings will be updated as incoming data is added. As a validity check of qualitative results, we will check relevant data interpretations against all new data using a constant comparison approach [64]. We will note similarities and differences of implementation feasibility between practice sites based on clinic characteristics and from data provided in interviews. Each quarter all quantitative and qualitative results will be summarized in brief reports to be shared with the research team for reflections on any changes needed. These analyses represent ongoing monitoring and feedback to inform refinements of the implementation strategy and clinical trial procedures to refine implementation strategy to better fit local needs and contexts.

Quantitative analysis

Descriptive statistics will be used to summarize patient and clinic characteristics. We will declare our intervention a success if at least 25% of those unscreened are screened at 12-month follow-up in this difficult to reach population. We will declare the optimization of screening a success if 15% of those unscreened are screened with a colonoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy at 12-months. Overall improvement metrics are comparable to improvements in previous CRC screening implementation studies in FQHCs [65, 66]. At baseline, we will calculate average screening rates and their confidence intervals across all practice sites in intent to treat analyses and at 12-months we will assess screening rates and their confidence intervals for all sites. The confidence intervals will be compared to 25%. We will compare differences in CRC screening by glucose control, sex, and race/ethnicity.

Power calculations

The value of information method [67] was utilized to select a sample size balancing the costs and feasibility goals of the trial. This sample size (e.g., six clinic sites, assuming at least n = 30 patient in each) is sufficient to generate preliminary estimates of the estimated effect (80% confidence interval) of the implementation strategy on CRC screeningrates [68, 69]. In developing the power calculation, we assume equal numbers of patients (n = 50) per clinic (the anticipated number of eligible patients, n = 450 CRC screening eligible, with > 10% diabetes diagnosis). Of those with diabetes, we expect 40% to be up-to-date with screening guidelines based on the average rate of CRC screening in FQHCs [70]. Thus, the target sample size is n = 30 patients in each FQHC.

Discussion

This study aims to optimize CRC screening using the engagement of multi-level stakeholders (patients, clinicians, staff in FQHCs) and using an implementation mapping during the exploration and preparation phases prior to implementation [37]. This project is innovative in several key ways. Regarding conceptual innovation, few studies have included CRC screening as a component of diabetes care prior to CRC diagnosis [71, 72], while many have focused on improving CRC screening for average risk adults in FQHCs [65, 66, 73,74,75,76,77,78,79].An EPIS framework systematic review concluded that attention to planning EBP use is “infrequent though critical [80].” FQHC implementation of CRC screening programs focus on achieving the Uniform Data System (UDS) targets, which do not distinguish patients at greater risk for CRC in the “average-risk” patient population [70, 81]. Metrics for UDS CRC screening program are also cross-sectional and collected as separate metrics unrelated to diabetes care or annual stool-based testing adherence. For FIT and FOBT stool-based CRC screening strategies to be clinically effective and for their mortality reductions to be realized sustained annual adherence is required, which has been proven difficult to accomplish in safety-net primary care settings [12, 13]. Additionally, few FQHCs formally assess factors related screening prior to implementing improvement interventions [82]. This study aims to optimize CRC prevention using the engagement of multi-level stakeholders (patients, clinicians, staff in FQHCs) and using an implementation mapping during the exploration and preparation phases prior to implementation [37].

Despite being the most studied evidence-based cancer screening in the National Institutes of Health implementation science portfolio, no systematic studies have integrated CRC screening and diabetes evidence-based approaches to prioritize preventive care for patients with diabetes in the primary care safety-net. To date, research has focused on overall CRC guideline adherence, relying on an ‘all boats rise’ approach despite the failures of such strategies to achieve improvements in chronic disease targets [83]. In contrast, this study focuses on optimizing CRC screening using targeted implementation strategies to address disparities among individuals with diabetes to promote health equity.

Study findings are poised to inform the develop scalable, equitable approaches to CRC screening in safety-net primary care settings. If successful, next steps will include testing the scalability and sustainability in federally qualified health centers nationally. Further, this approach can be adapted as a model to investigate the development of targeted cancer prevention strategies in additional chronically ill priority populations.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- CRC:

-

Colorectal cancer

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- FIT:

-

Fecal immunochemical tests

- FIT-DNA:

-

Fecal immunochemical test stool DNA testing

- FQHC:

-

Federally qualified health centers

- FS:

-

Flexible sigmoidoscopy

- gFOBT:

-

Guaiac fecal occult blood tests

- IPG:

-

Implementation Planning Group

- HER:

-

Electronic health record

- EBP:

-

Evidence-based practice

- ERIC:

-

Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change

- EPIS:

-

Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment

- NJPCRN:

-

New Jersey Primary Care Research Network

- SURE:

-

CRC4D: Strategic Use of Resources for Enhanced ColoRectal Cancer Screening in Patients with Diabetes

- SPIRIT:

-

Standard Protocol Items: Recommendation for Interventional Trials

- UDS:

-

Uniform Data System

- USPSTF:

-

U.S. Preventive Services Taskforce

References

Spanakis EK, Golden SH. Race/ethnic difference in diabetes and diabetic complications. Curr Diab Rep. 2013;13(6):814–23.

Karter AJ, Ferrara A, Liu JY, Moffet HH, Ackerson LM, Selby JV. Ethnic disparities in diabetic complications in an insured population. JAMA. 2002;287(19):2519–27.

Miller EA, Tarasenko YN, Parker JD, Schoendorf KC. Diabetes and colorectal cancer screening among men and women in the USA: National Health interview survey: 2008, 2010. Cancer Causes Control. 2014;25(5):553–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-014-0360-z.

Davidson KW, Barry MJ, Mangione CM, Cabana M, Caughey AB, Davis EM, Donahue KE, Doubeni CA, Krist AH, Kubik M, Li L, Ogedegbe G, Owens DK, Pbert L, Silverstein M, Stevermer J, Tseng CW, Wong JB. Screening for Colorectal Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2021;325(19):1965–77. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.6238. PubMed PMID: 34003218.

May FP, Yang L, Corona E, Glenn BA, Bastani R. Disparities in Colorectal Cancer Screening in the United States before and after implementation of the Affordable Care Act. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology; 2019.

Huang ES, Zhang Q, Brown SE, Drum ML, Meltzer DO, Chin MH. The cost-effectiveness of improving diabetes care in U.S. federally qualified community health centers. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(6 Pt 1):2174-93; discussion 294–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00734.x. PubMed PMID: 17995559; PMCID: PMC2151395.

Liu P-H, Wang J-D, Keating NL. Expected years of life lost for six potentially preventable cancers in the United States. Prev Med. 2013;56(5):309–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.02.003.

Boakye D, Rillmann B, Walter V, Jansen L, Hoffmeister M, Brenner H. Impact of comorbidity and frailty on prognosis in colorectal cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Treat Rev. 2018;64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2018.02.003. Epub 2018/02/10. :30 – 9.

Jiang Y, Ben Q, Shen H, Lu W, Zhang Y, Zhu J. Diabetes mellitus and incidence and mortality of colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Eur J Epidemiol. 2011;26(11):863–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-011-9617-y.

Mills KT, Bellows CF, Hoffman AE, Kelly TN, Gagliardi G. Diabetes mellitus and colorectal cancer prognosis: a meta-analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56(11):1304–19. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182a479f9.

Shaukat A, Mongin SJ, Geisser MS, Lederle FA, Bond JH, Mandel JS, Church TR. Long-term mortality after screening for colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(12):1106–14. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1300720. PubMed PMID: 24047060.

Jensen CD, Corley DA, Quinn VP, Doubeni CA, Zauber AG, Lee JK, Zhao WK, Marks AR, Schottinger JE, Ghai NR, Lee AT, Contreras R, Klabunde CN, Quesenberry CP, Levin TR, Mysliwiec PA. Fecal immunochemical test program performance over 4 rounds of Annual Screening: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(7):456–63. https://doi.org/10.7326/M15-0983. PubMed PMID: 26811150; PMCID: PMC4973858.

Inadomi JM, Vijan S, Janz NK, Fagerlin A, Thomas JP, Lin YV, Munoz R, Lau C, Somsouk M, El-Nachef N, Hayward RA. Adherence to colorectal cancer screening: a randomized clinical trial of competing strategies. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(7):575–82. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2012.332. Epub 2012/04/12.

Shroff J, Thosani N, Batra S, Singh H, Guha S. Reduced incidence and mortality from colorectal cancer with flexible-sigmoidoscopy screening: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(48):18466–76. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i48.18466. PubMed PMID: 25561818.

Doubeni CA, Fedewa SA, Levin TR, Jensen CD, Saia C, Zebrowski AM, Quinn VP, Rendle KA, Zauber AG, Becerra-Culqui TA, Mehta SJ, Fletcher RH, Schottinger J, Corley DA. Modifiable failures in the colorectal Cancer screening process and their Association with risk of death. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(1):63–e746. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2018.09.040.

Gorin SS. Multilevel approaches to reducing Diagnostic and Treatment Delay in Colorectal Cancer. Annals Family Med. 2019;17(5):386–9.

Breen N, Skinner CS, Zheng Y, Inrig S, Corley DA, Beaber EF, Garcia M, Chubak J, Doubeni C, Quinn VP, Haas JS, Li CI, Wernli KJ, Klabunde CN. Time to follow-up after Colorectal Cancer Screening by Health Insurance Type. Am J Prev Med. 2019;56(5):e143–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2019.01.005.

Swartz AW, Eberth JM, Josey MJ, Strayer SM. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(8):602–3. https://doi.org/10.7326/m17-0859. Epub 2017/08/23. Reanalysis of All-Cause Mortality in the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force 2016 Evidence Report on Colorectal Cancer Screening.

Swartz AW, Eberth JM, Strayer SM. Preventing colorectal cancer or early diagnosis: Which is best? A re-analysis of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Evidence Report. Prev Med. 2019;118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.10.014. Epub 2018/10/28. :104 – 12.

Lin JS, Piper MA, Perdue LA, Rutter CM, Webber EM, O’Connor E, Smith N, Whitlock EP. Screening for colorectal cancer: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;315(23):2576–94.

Atkin WS, Edwards R, Kralj-Hans I, Wooldrage K, Hart AR, Northover JMA, Parkin DM, Wardle J, Duffy SW, Cuzick J. Once-only flexible sigmoidoscopy screening in prevention of colorectal cancer: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;375(9726):1624–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60551-X.

Schoen RE, Pinsky PF, Weissfeld JL, Yokochi LA, Church T, Laiyemo AO, Bresalier R, Andriole GL, Buys SS, Crawford ED, Fouad MN, Isaacs C, Johnson CC, Reding DJ, O’Brien B, Carrick DM, Wright P, Riley TL, Purdue MP, Izmirlian G, Kramer BS, Miller AB, Gohagan JK, Prorok PC, Berg CD. Colorectal-Cancer incidence and mortality with screening flexible sigmoidoscopy. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(25):2345–57. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1114635. PubMed PMID: 22612596.

Segnan N, Armaroli P, Bonelli L, Risio M, Sciallero S, Zappa M, Andreoni B, Arrigoni A, Bisanti L, Casella C, Crosta C, Falcini F, Ferrero F, Giacomin A, Giuliani O, Santarelli A, Visioli CB, Zanetti R, Atkin WS, Senore C, Group atSW. Once-only sigmoidoscopy in Colorectal Cancer Screening: follow-up findings of the Italian randomized controlled Trial—SCORE. JNCI: J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(17):1310–22. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djr284.

Holme Ø, Løberg M, Kalager M, Bretthauer M, Hernán MA, Aas E, Eide TJ, Skovlund E, Schneede J, Tveit KM, Hoff G. Effect of flexible Sigmoidoscopy Screening on Colorectal Cancer incidence and mortality: a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2014;312(6):606–15. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.8266.

Nishihara R, Wu K, Lochhead P, Morikawa T, Liao X, Qian ZR, Inamura K, Kim SA, Kuchiba A, Yamauchi M, Imamura Y, Willett WC, Rosner BA, Fuchs CS, Giovannucci E, Ogino S, Chan AT. Long-term colorectal-cancer incidence and mortality after lower endoscopy. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(12):1095–105. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1301969. PubMed PMID: 24047059.

Gwede CK, Davis SN, Quinn GP, Koskan AM, Ealey J, Abdulla R, Vadaparampil ST, Elliott G, Lopez D, Shibata D, Roetzheim RG, Meade CD. Tampa Bay Community Cancer Network P. making it work: Health Care Provider perspectives on strategies to increase colorectal Cancer screening in federally qualified Health centers. J Cancer Educ. 2013;28(4):777–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-013-0531-8.

Arnold CL, Rademaker A, Wolf MS, Liu D, Lucas G, Hancock J, Davis TC. Final results of a 3-Year literacy-informed intervention to promote Annual Fecal Occult Blood Test Screening. J Community Health. 2016;41(4):724–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-015-0146-6. PubMed PMID: 26769026; PMCID: PMC4930386.

Singal AG, Gupta S, Skinner CS, Ahn C, Santini NO, Agrawal D, Mayorga CA, Murphy C, Tiro JA, McCallister K, Sanders JM, Bishop WP, Loewen AC, Halm EA. Effect of Colonoscopy Outreach vs Fecal Immunochemical Test Outreach on Colorectal Cancer Screening Completion: a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2017;318(9):806–15. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.11389. PubMed PMID: 28873161; PMCID: PMC5648645.

Green BB, Anderson ML, Cook AJ, Chubak J, Fuller S, Meenan RT, Vernon SW. A centralized mailed program with stepped increases of support increases time in compliance with colorectal cancer screening guidelines over 5 years: a randomized trial. Cancer. 2017;123(22):4472–80. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30908. PubMed PMID: 28753230; PMCID: PMC5673524.

Aarons GA, Hurlburt M, Horwitz SM. Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38(1):4–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-010-0327-7. Epub 2011/01/05.

Holtrop JS, Rabin BA, Glasgow RE. Dissemination and implementation science in primary Care Research and Practice: contributions and opportunities. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31(3):466–78. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2018.03. .170259. PubMed PMID: 29743229.

Dearing JW, Kreuter MW. Designing for diffusion: how can we increase uptake of cancer communication innovations? Patient Educ Couns. 2010;81 Suppl:S100-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2010.10.013. PubMed PMID: 21067884; PMCID: 3000559.

Brownson RC, Jacobs JA, Tabak RG, Hoehner CM, Stamatakis KA. Designing for dissemination among public health researchers: findings from a national survey in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(9):1693–9. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.301165. PubMed PMID: 23865659; PMCID: 3966680.

Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, Damschroder LJ, Smith JL, Matthieu MM, Proctor EK, Kirchner JE. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1.

Adams SA, Rohweder CL, Leeman J, Friedman DB, Gizlice Z, Vanderpool RC, Askelson N, Best A, Flocke SA, Glanz K, Ko LK, Kegler M. Use of evidence-based interventions and implementation strategies to increase colorectal Cancer screening in federally qualified Health centers. J Community Health. 2018;43(6):1044–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-018-0520-2. PubMed PMID: 29770945; PMCID: PMC6239992.

Wallerstein N, Duran B. Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: the intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(Suppl 1). https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2009.184036. Epub 2010/02/12. :S40-6.

Fernandez ME, Ten Hoor GA, van Lieshout S, Rodriguez SA, Beidas RS, Parcel G, Ruiter RAC, Markham CM, Kok G. Implementation mapping: using intervention mapping to develop implementation strategies. Front Public Health. 2019;7:158. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00158. Epub 2019/07/06.

Balasubramanian BA, Chase SM, Nutting PA, Cohen DJ, Strickland PA, Crosson JC, Miller WL, Crabtree BF, Team US. Using learning teams for reflective adaptation (ULTRA): insights from a team-based change management strategy in primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(5):425–32. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1159. Epub 2010/09/17.

Mittman BS. Creating the evidence base for quality improvement collaboratives. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(11):897–901. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-140-11-200406010-00011. Epub 2004/06/03.

Bate JOV, Cleary P, Cretin P, Gustafson S, McInnes D, McLeod K, Molfenter H, Plsek T, Robert P, Shortell G, Wilson S. Quality collaboratives: lessons from research. Qual Saf Health Care. 2002;11(4):345–51. PubMed PMID: 12468695; PMCID: PMC1757995.

Shaw EK, Chase SM, Howard J, Nutting PA, Crabtree BF. More black box to explore: how quality improvement collaboratives shape practice change. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25(2):149–57. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2012.02.110090. PubMed PMID: 22403195; PMCID: PMC3362133. Epub 2012/03/10.

Chase SM, Crabtree BF, Stewart EE, Nutting PA, Miller WL, Stange KC, Jaen CR. Coaching strategies for enhancing practice transformation. Fam Pract. 2015;32(1):75–81. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmu062. Epub 2014/10/05.

Chase SM, Miller WL, Shaw E, Looney A, Crabtree BF. Meeting the challenge of practice quality improvement: a study of seven family medicine residency training practices. Acad Med. 2011;86(12):1583–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31823674fa. Epub 2011/10/28.

Dickinson WP, Dickinson LM, Nutting PA, Emsermann CB, Tutt B, Crabtree BF, Fisher L, Harbrecht M, Gottsman A, West DR. Practice facilitation to improve diabetes care in primary care: a report from the EPIC randomized clinical trial. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(1):8–16. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1591. Epub 2014/01/22.

Howard J, Shaw EK, Clark E, Crabtree BF. Up close and (inter)personal: insights from a primary care practice’s efforts to improve office relationships over time, 2003–2009. Qual Manag Health Care. 2011;20(1):49–61. https://doi.org/10.1097/QMH.0b013e31820311e6. Epub 2010/12/31.

Nutting PA, Crabtree BF, Stewart EE, Miller WL, Palmer RF, Stange KC, Jaen CR. Effect of facilitation on practice outcomes in the National Demonstration Project model of the patient-centered medical home. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1119. PubMed PMID: 20530393; PMCID: PMC2885723. Suppl 1:S33-44; S92Epub 2010/06/16.

Shaw E, Looney A, Chase S, Navalekar R, Stello B, Lontok O, Crabtree B. In the moment’: an analysis of Facilitator Impact during a quality improvement process. Group Facil. 2010;10:4–16. Epub 2010/01/01. PubMed PMID: 22557936; PMCID: PMC3340924.

Shaw EK, Ohman-Strickland PA, Piasecki A, Hudson SV, Ferrante JM, McDaniel RR Jr., Nutting PA, Crabtree BF. Effects of facilitated team meetings and learning collaboratives on colorectal cancer screening rates in primary care practices: a cluster randomized trial. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(3):220–8. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1505. S1-8. Epub 2013/05/22.

Agulnik A, Boykin D, O’Malley DM, Price J, Yang M, McKone M, Curran G, Ritchie MJ. Virtual facilitation best practices and research priorities: a scoping review. Implement Sci Commun. 2024;5(1):16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-024-00551-6.

Jamtvedt G, Young JM, Kristoffersen DT, O’Brien MA, Oxman AD. Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;2CD000259. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000259.pub2. Epub 2006/04/21.

Hysong SJ, Best RG, Pugh JA. Audit and feedback and clinical practice guideline adherence: making feedback actionable. Implement Sci. 2006;1:9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-1-9. Epub 2006/05/26.

Balasubramanian BA, Cohen DJ, Davis MM, Gunn R, Dickinson LM, Miller WL, Crabtree BF, Stange KC. Learning evaluation: blending quality improvement and implementation research methods to study healthcare innovations. Implement Sci. 2015;10:31. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0219-z. Epub 2015/04/19.

Chambers DA, Glasgow RE, Stange KC. The dynamic sustainability framework: addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implement Sci. 2013;8:117. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-117. Epub 2013/10/04.

Aarons GA, Green AE, Trott E, Willging CE, Torres EM, Ehrhart MG, Roesch SC. The roles of System and Organizational Leadership in system-wide evidence-based intervention sustainment: a mixed-method study. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2016;43(6):991–1008. PubMed PMID: 27439504; PMCID: 5494253.

Smith JD, Polaha J. Using implementation science to guide the integration of evidence-based family interventions into primary care. Fam Syst Health. 2017;35(2):125–35. https://doi.org/10.1037/fsh0000252. PubMed PMID: 28617015; PMCID: 5473179.

Stirman SW, Gutner CA, Langdon K, Graham JR. Bridging the Gap between Research and Practice in Mental Health Service settings: an overview of developments in implementation theory and research. Behav Ther. 2016;47(6):920–36. PubMed PMID: 27993341.

Jaen CR, Crabtree BF, Palmer RF, Ferrer RL, Nutting PA, Miller WL, Stewart EE, Wood R, Davila M, Stange KC. Methods for evaluating practice change toward a patient-centered medical home. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(Suppl 1):S9–20. S92. Epub 2010/06/16. doi: 8/Suppl_1/S9 [pii]. 1370/afm. 1108. PubMed PMID: 20530398; PMCID: 2885721.

Li R, Simon J, Bodenheimer T, Gillies RR, Casalino L, Schmittdiel J, Shortell SM. Organizational factors affecting the adoption of diabetes care management processes in physician organizations. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(10):2312–6. Epub 2004/09/29. doi: 27/10/2312 [pii]. PubMed PMID: 15451893.

Rittenhouse DR, Casalino LP, Gillies RR, Shortell SM, Lau B. Measuring the medical home infrastructure in large medical groups. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(5):1246–58. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.27.5.1246. Epub 2008/09/11.

EvidenceNOW: Change Process Capability Questionnaire (CPC-Q). Scoring Guidance. Content last reviewed February 2019. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Rockville, MD. https://www.ahrq.gov/evidencenow/results/research/cpcq-scoring.html.

Nutting PA, Crabtree BF, Miller WL, Stewart EE, Stange KC, Jaén CR. Journey to the patient-centered medical home: a qualitative analysis of the experiences of practices in the National Demonstration Project. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(Suppl 1). https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1075. PubMed PMID: 20530394; PMCID: PMC2885728. S45-56; s92.

Aarons GA, Ehrhart MG, Farahnak LR. The implementation Leadership Scale (ILS): development of a brief measure of unit level implementation leadership. Implement Sci. 2014;9(1):45. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-9-45. Epub 20140414.

Yin RK. Case study research and applications. Sage Thousand Oaks, CA; 2018.

Glaser BG. The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Soc Probl. 1965;12(4):436–45.

Coronado GD, Petrik AF, Vollmer WM, Taplin SH, Keast EM, Fields S, Green BB. Effectiveness of a Mailed Colorectal Cancer Screening Outreach Program in Community Health clinics: the STOP CRC Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(9):1174–81. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3629.

Coronado GD, Rivelli JS, Fuoco MJ, Vollmer WM, Petrik AF, Keast E, Barker S, Topalanchik E, Jimenez R. Effect of Reminding Patients to Complete Fecal Immunochemical Testing: A Comparative Effectiveness Study of Automated and Live Approaches. Journal of general internal medicine. 2018;33(1):72 – 8. Epub 2017/10/10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4184-x. PubMed PMID: 29019046.

Rothery C, Strong M, Koffijberg HE, Basu A, Ghabri S, Knies S, Murray JF, Schmidler GDS, Steuten L, Fenwick E. Value of information analytical methods: report 2 of the ISPOR value of information analysis emerging good practices task force. Value Health. 2020;23(3):277–86.

Bacchetti P. Current sample size conventions: flaws, harms, and alternatives. BMC Med. 2010;8:17-. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-8-17. PubMed PMID: 20307281.

Moore CG, Carter RE, Nietert PJ, Stewart PW. Recommendations for planning pilot studies in clinical and translational research. Clin Transl Sci. 2011;4(5):332–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-8062.2011.00347. .x. PubMed PMID: 22029804.

Administration HRaS. Health Center Program. 2019.

Hong YR, Sonawane KB, Holcomb DR, Deshmukh AA. Effect of multimodal information delivery for diabetes care on colorectal cancer screening uptake among individuals with type 2 diabetes. Prev Med Rep. 2018;11:89–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2018.05.008. Epub 2018/07/10.

Kiran T, Kopp A, Moineddin R, Glazier RH. Longitudinal evaluation of physician payment reform and team-based care for chronic disease management and prevention. CMAJ. 2015;187(17):E494–502. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.150579. Epub 2015/09/21.

Taplin SH, Haggstrom D, Jacobs T, Determan A, Granger J, Montalvo W, Snyder WM, Lockhart S, Calvo A. Implementing colorectal cancer screening in community health centers: addressing cancer health disparities through a regional cancer collaborative. Med Care. 2008;46(9 Suppl 1):S74–83. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817fdf68. PubMed PMID: 18725837.

Coury J, Schneider JL, Rivelli JS, Petrik AF, Seibel E, D’Agostini B, Taplin SH, Green BB, Coronado GD. Applying the Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) approach to a large pragmatic study involving safety net clinics. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):411. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2364-3. Epub 2017/06/21.

Davis T, Arnold C, Rademaker A, Bennett C, Bailey S, Platt D, Reynolds C, Liu D, Carias E, Bass P III. Improving colon cancer screening in community clinics. Cancer. 2013;119(21):3879–86.

Davis SN, Christy SM, Chavarria EA, Abdulla R, Sutton SK, Schmidt AR, Vadaparampil ST, Quinn GP, Simmons VN, Ufondu CB, Ravindra C, Schultz I, Roetzheim RG, Shibata D, Meade CD, Gwede CK. A randomized controlled trial of a multicomponent, targeted, low-literacy educational intervention compared with a nontargeted intervention to boost colorectal cancer screening with fecal immunochemical testing in community clinics. Cancer. 2017;123(8):1390–400. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30481. Epub 2016/12/01.

Gwede CK, Sutton SK, Chavarria EA, Gutierrez L, Abdulla R, Christy SM, Lopez D, Sanchez J, Meade CD. A culturally and linguistically salient pilot intervention to promote colorectal cancer screening among latinos receiving care in a federally qualified Health Center. Health Educ Res. 2019;34(3):310–20. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyz010. PubMed PMID: 30929015.

Dolan NC, Ramirez-Zohfeld V, Rademaker AW, Ferreira MR, Galanter WL, Radosta J, Eder MM, Cameron KA. The effectiveness of a physician-only and physician-patient intervention on Colorectal Cancer Screening discussions between providers and African American and latino patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(12):1780–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3381-8. Epub 2015/05/19.

Baker DW, Brown T, Buchanan DR, Weil J, Balsley K, Ranalli L, Lee JY, Cameron KA, Ferreira MR, Stephens Q. Comparative effectiveness of a multifaceted intervention to improve adherence to annual colorectal cancer screening in community health centers: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(8):1235–41.

Moullin JC, Dickson KS, Stadnick NA, Rabin B, Aarons GA. Systematic review of the Exploration, Preparation, implementation, sustainment (EPIS) framework. Implement Science: IS. 2019;14(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-018-0842-6. PubMed PMID: 30611302.

Riehman KS, Stephens RL, Henry-Tanner J, Brooks D. Evaluation of Colorectal Cancer Screening in federally qualified Health centers. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54(2):190–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2017.10.007.

Leeman J, Askelson N, Ko LK, Rohweder CL, Avelis J, Best A, Friedman D, Glanz K, Seegmiller L, Stradtman L, Vanderpool RC. Understanding the processes that Federally Qualified Health Centers use to select and implement colorectal cancer screening interventions: a qualitative study. Transl Behav Med. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1093/tbm/ibz023. PubMed PMID: 30794725. Epub 2019/02/23.

Calman NS, Hauser D, Schussler L, Crump C. A risk-based intervention approach to eliminate diabetes health disparities. Prim Health care Res Dev. 2018;19(5):518–22.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our FQHC participants for informing the intervention and their contributions to this work.

Funding

This research is supported by the National Cancer Institute (K99 CA256043/R00CA256043) The contents are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement, by the funders.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.O. conceptualized study and acquired funding; D.O and S.K. Writing – original draft; BFC, SK, PO, JF, SVH, AK reviewed, edited, and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This protocol has been approved by the Rutgers University Institutional. Review Board (Pro2020002075). All study participants will be asked to provide informed consent prior to participation in any phase of this research. All authors have completed ethics training. This research will be performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

O’Malley, D.M., Crabtree, B.F., Kaloth, S. et al. Strategic use of resources to enhance colorectal cancer screening for patients with diabetes (SURE: CRC4D) in federally qualified health centers: a protocol for hybrid type ii effectiveness-implementation trial. BMC Prim. Care 25, 242 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-024-02496-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-024-02496-0