Abstract

Background

Primary care actors can play a major role in developing and promoting access to Self-Management Education and Support (SMES) programmes for people with chronic disease. We reviewed studies on SMES programmes in primary care by focusing on the following dimensions: models of SMES programmes in primary care, SMES team’s composition, and participants’ characteristics.

Methods

For this mixed-methods rapid review, we searched the PubMed and Cochrane Library databases to identify articles in English and French that assessed a SMES programme in primary care for four main chronic diseases (diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular disease and/or respiratory chronic disease) and published between 1 January 2013 and 31 December 2021. We excluded articles on non-original research and reviews. We evaluated the quality of the selected studies using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool. We reported the study results following the PRISMA guidelines.

Results

We included 68 studies in the analysis. In 46/68 studies, a SMES model was described by focusing mainly on the organisational dimension (n = 24). The Chronic Care Model was the most used organisational model (n = 9). Only three studies described a multi-dimension model. In general, the SMES team was composed of two healthcare providers (mainly nurses), and partnerships with community actors were rarely reported. Participants were mainly patients with only one chronic disease. Only 20% of the described programmes took into account multimorbidity. Our rapid review focused on two databases and did not identify the SMES programme outcomes.

Conclusions

Our findings highlight the limited implication of community actors and the infrequent inclusion of multimorbidity in the SMES programmes, despite the recommendations to develop a more interdisciplinary approach in SMES programmes. This rapid review identified areas of improvement for SMES programme development in primary care, especially the privileged place of nurses in their promotion.

Trial registration

PROSPERO 2021 CRD42021268290.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The number of people with chronic diseases has been rising worldwide [1], and one third of them has more than one chronic condition [2]. Several international scientific societies recommend Self-Management Education and Support (SMES) interventions because they can improve the quality of life of people with chronic conditions [3,4,5]. SMES programmes are defined as the provision of the foundation to help people manage their chronic disease, and guide their health-related decisions and activities [6]. However, several authors highlighted that attendance to SMES programmes by patients is low, despite their widely acknowledged benefits [7, 8]. Primary care actors can play a major role in developing SMES programmes and improving the patients’ access to these interventions [6, 9, 10].

However, to better meet the needs of people living with chronic diseases, the different dimensions of SMES interventions in primary care need to be reconsidered [11]. First, the healthcare organisation (HCO) is a major category to consider when developing a model of SMES delivery. In the Chronic Care Model (CCM), created by Wagner in 2001 and revisited in 2019, the delivery system design, decision support and clinical information system are included in the HCO [12]. However, in 2018, Reynolds showed in a systematic review that more evidence is needed about the impact of the SMES programme organisational dimension on professional and patient outcomes in primary care [13]. Second, several authors stated that SMES programmes should be based on the social cognitive theory, particularly the self-efficacy concept [14,15,16]. Yet, in 2019, a systematic review of randomised controlled trials found that none of the studied SMES programmes included a theoretical or conceptual framework [17]. Third, although the educative content of SMES programmes seems well established, the educational theory developed by the team to accompany patients in their skill and competence development is rarely described [15]. These three dimensions (organisational, social/behavioural, and educational), which can be combined or not by authors, must all be taken into account because the model of care can influence the results of SMES programmes [11].

Besides the models, the SMES team composition also needs to be considered. As underlined by the CCM model, collaboration among the primary care healthcare providers (HCP) is a major component of the model [12]. The emergence of new HCPs in primary care offers new workforce and the opportunity to rethink the SMES team collaboration [7, 18]. However, in 2022, the scoping review by Longhini et al. showed that the SMES team members’ roles and responsibilities in delivering care were not precisely described in studies on SMES [19]. In addition, the participation of community actors should be encouraged and strengthened. This will help the population to better identify the proposed SMES programme and the HCP team to better adapt the SMES activities to the population [20]. Yet, different studies showed the lack of collaboration between HCPs and community actors, especially social services [13, 19, 21].

Lastly, the profile of participants also should be taken into account in the SMES model due to the current primary care challenges, particularly multimorbidity. In 2014, Rijken et al. stressed that the development of a multimorbidity approach in SMES programmes is a priority [14, 22]. Due to the primary care teams’ key role in the management of people with multimorbidity, HCO must undergo a radical change [23, 24]. Indeed, the care of patients with multimorbidity is time-consuming and multimorbidity management might create difficulties among primary care providers [25, 26].

Previous studies highlighted a gap between the patients’ needs, due to the increasing number of people with chronic diseases, and the type of SMES interventions implemented in primary care. More data on the SMES model dimensions (organisational, social/behavioural and educational), SMES team composition and roles, and participants’ characteristics are needed.

The objective of this rapid review was to identify studies on SMES programmes for people with chronic diseases in primary care, with a specific focus on the different dimensions of the models, the SMES team composition, and the participants in order to highlight elements that need to be improved.

Method

This rapid review was performed following the World Health Organisation practical guide for rapid reviews [27]. This approach was chosen due to the time and skills necessary to execute a systematic review in the context of the rapid increase of the volume of publications on SMES in primary care [13, 28]. This guide lists six different rapid review approaches with different feasibility, timeliness, comprehensiveness and quality assessment levels. For this rapid review, approach 6 was chosen because it focuses on comprehensiveness (i.e. wide consideration of the subject) and quality assessment (i.e. good measurement and evaluation of the quality of the selected studies). Therefore, our search strategy focused on more than one database, with date and language selection. Two independent reviewers (EA, JS) selected the articles, performed data abstraction and bias assessment using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) [27]. The PRISMA guidelines were followed for reporting the study results [29] (Additional files 1 and 2). The protocol of this rapid review was registered in PROSPERO and can be accessed at: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?RecordID=268290.

Data sources and search strategy

Two databases were searched: PubMed and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. PubMed was chosen because it is the second source of health education publications and using other databases to identify studies on therapeutic interventions does not significantly change the search outcome [30, 31]. The Cochrane database was chosen because of its systematic approach for reviewing randomised controlled trials.

All authors and a documentalist (VDA) contributed to defining the following search strategy: only articles in English and French, and published from 1 January 2013 to 31 December 2021. The beginning date (1 January 2013) was chosen because following an international survey in 2014, it was recommended that SMES programmes in primary care should better address multimorbidity and that such programmes should be better integrated in the community [14].

The search strategy covered the following four domains: (1) primary care or primary healthcare; (2) models considered according to their organisational or educational dimension; (3) self-management under various names due to naming inconsistency in the literature [32]; in our article, self-management has been chosen as the main term, due to its focus on chronic disease, whereas self-care mainly expresses the ability of people to prevent a disease [15, 33]; and (4) the four most common chronic conditions: diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular disease, and respiratory chronic disease (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma) [1]. For both databases, the following string of keywords was used: ((‘primary health care’[MH] OR ‘primary health care’[TW] OR ‘primary care’[TW]) AND (‘organisational model’[TW] OR ‘models, organisational’[MH] OR ‘models, educational’[MH] OR ‘educational model’[TW] OR (‘organisat*’[TW] AND ‘model*’[TW]) OR (‘educ*’[TW] AND ‘model*’[TW]) OR (‘theor*’[TW] AND ‘model*’[TW])) AND (‘patient education as topic’[MH] OR ‘patient education’[TW] OR ‘patient teaching’ [TW] OR ‘self-care’[MH] OR ‘self-care’[TW] OR ‘self-management’[MH] OR ‘self-management’[TW] OR ‘health education’[MH] OR ‘health education’[TW] OR ‘health promotion’[MH] OR ‘health promotion’ [TW]) AND (‘non communicable diseases’ [MH] OR ‘chronic disease’ [MH] OR ‘multimorbidity’ [MH] OR ‘chronic*’[TW] OR ‘diabetes*’ [TW] OR ‘cancer’ [TW] OR ‘cardiovascular disease’ [TW] OR ‘asthma’ [TW] OR ‘chronic obstructive pulmonary disease’ [TW])).

Study selection

Citations were downloaded and screened in Rayyan® (a web-based tool for evidence synthesis, https://www.rayyan.ai/). Two reviewers (EA, JS) independently screened titles and abstracts and checked the exclusion and inclusion criteria (see below). Conflicts were solved by discussion. When the two reviewers could not decide whether an article should be retained on the basis of its title and abstract, they screened the full text.

Inclusion criteria were:

-

Studies on primary care, according to the definition by Starfield et al.: the first contact, realising continuity and coordination of care, and having a global and community approach [34].

-

Studies on one of the four most prevalent chronic diseases, or on multimorbidity [1].

-

Studies that evaluated a SMES intervention, as defined by the American Diabetes Association, using qualitative and/or quantitative methods [6].

Exclusion criteria were:

-

Review articles.

-

Articles that did not report results from original research, such as protocol studies, expert opinion articles and recommendations made by authors.

-

Studies on routine care without a dedicated SMES intervention.

For each article that passed the initial screening, two reviewers (EA and JS) independently read the full text to determine whether it met the inclusion or exclusion criteria. In case of conflict between reviewers concerning the inclusion of a study, a third person brought his expertise (RGy).

Data abstraction, quality assessment and analysis

Data abstraction from the selected articles was carried out by two authors (EA, JS) and then all authors analysed the included studies in four steps. First, the quality of the included studies was evaluated using the MMAT [35]. This scale allows assessing quantitative and qualitative methods in a mixed-methods approach (Additional file 3). Second, the model of each SMES programme was recorded, without predefined categories. RGz (professor in public health) particularly focused on the organisational models and RGy (professor in health education) focused on the social and health behaviour models and educational models. Third, the characteristics of the SMES team composition were extracted: number and occupation of each member, presence of a patient partner [36], community partner, and/or hospital participation. Fourth, the following data were extracted from the studies: participants’ characteristics (patient, caregiver), number of chronic diseases (one or multimorbidity), recruitment procedure, and programme size as defined in the primary care classification (micro level: < 50,000 habitants and/or < 5 primary care centres; meso level: > 50,000 habitants and/or ≥ 5 and < 10 primary care centres; and macro level: > 10 primary care centres) proposed by Jan De Maeseneer et al. [37].

All data were collected in an Excel file and shared among authors, in a blinded way.

Results

Study selection

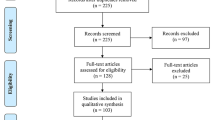

The initial search in the PubMed and Cochrane databases resulted in the inclusion of 887 studies, with no duplicate found (Fig. 1). After reading the title and abstract, 767 studies were excluded because they were not on chronic diseases (n = 308) or primary healthcare (n = 192), did not assess a SMES programme (n = 186), did not describe results from original research (n = 77), or were literature reviews (n = 4). This resulted in the selection of 120 articles, but only 116 articles were retained because the full text of four articles could not be obtained even after contacting the authors. After reading the full text of the 116 articles, 48 articles were excluded because they did not evaluate a SMES programme (n = 32), the same programme had already been evaluated in another article (n = 7), they did not concern primary healthcare (n = 5) or a chronic disease (n = 1), and they did not present results from original research (n = 3).

Study characteristics and quality

Among the 68 selected studies, 36 were carried out in North America (United States n = 30, Canada n = 5, Mexico n = 1,), 12 in Europe (United Kingdom n = 3, Netherlands n = 3, Spain n = 2, Belgium n = 1, Denmark n = 1, Italy n = 1, Sweden n = 1), 11 in Asia (Hong Kong n = 3, Japan n = 2, China n = 1, Malaysia n = 1, Philippines n = 1, Thailand n = 1), 5 in Oceania (Australia n = 3, American Samoa n = 1, New Zealand n = 1), 2 in South America (Brazil n = 2), 1 in Central America (Guatemala n = 1), and 1 Africa (South Africa n = 1). Study design was variable: quantitative non-randomised study (n = 26), quantitative randomised control trial (n = 25), mixed methods study (n = 7), qualitative study (n = 6), quantitative descriptive study (n = 3), and cost-effectiveness analysis (n = 1). The mean MMAT score was 3.4 [min 0, max 5].

SMES models, SMES teams, chronic condition(s), territory level

Table 1 provides an overview of the characteristics of the SMES models in the 68 studies retained for this rapid review. In 46 studies, a single-dimension model (n = 38) or multiple models (n = 8) were described. In the studies with multiple models, models were not combined in five studies, and were combined in a multi-dimension model in three studies. Among the 38 studies on a single-dimension model, 24 articles used an organisational model, 13 a social and health behaviour model, and 1 an educational model.

CCM was the most frequently used organisational model (n = 9). Organisational models were developed by the authors in five studies. In three studies, the organisational model consisted in adding one HCP. In seven studies, a pre-existing organisational model was used. The chronic disease self-management programme was the only model with a community-based approach [48]. The Teamlet model of primary care included one clinician and two health coaches [44]. Two models were implemented at the primary care practice level: the primary care medical home model [47] and the Iora health model [49]. In the support nucleus for the family healthcare model by the Brazilian ministry of health, a multidisciplinary educational health care team was added to the primary care practice [73]. Two models were implemented in secondary care: the Brisbane South Complex Diabetes Service model (integrated community and specialist model) [45] and the Telemedicine for Reach, Education, Access, and Treatment model (video consultations with a diabetes specialist and a diabetes educator) [46].

Among the studies that chose a social and health behaviour model (n = 13), ten used a behavioural model and three a social cognitive model. The most frequent behavioural model was the motivational approach [51], followed by the transtheoretical model of behaviour change [53]. One behavioural model was developed by the authors [74]. The three studies on social cognitive models used the self-efficacy model described by Bandura [55], the empowerment theory developed by Funnell [57], and the common sense model of sense-regulation [58].

Only one study described an educational model created by the authors [59].

The five studies with non-combined models used mostly social and health behaviour models. Three studies evaluated a multi-dimension model.

In the 68 studies, the mean number of HCPs in the SMES team was 2 (range: 1–7) (Table 2). They were mainly nurses (n = 36 studies), followed by dieticians (n = 17 studies), general practitioners (GP) (n = 13 studies), qualified peers (n = 12 studies), community health workers (n = 6 studies), peer leaders (n = 3 studies), health promoters (n = 2 studies), patient navigators (n = 1 study), and educators (n = 9 studies). Other HCP types were part of the SMES team in 13 studies: physiotherapists (n = 4), physical educators (n = 2), respiratory therapists (n = 2), podiatrists (n = 2), occupational therapists (n = 1), smoking cessation therapists (n = 1), and optometrists (n = 1). Pharmacists were included in 7 studies, health coaches in 6, medical assistants in 5 (including health technicians), and social workers in 3. Besides GPs, other physicians were included in the SMES team: endocrinologist (n = 1 study), health officer (n = 1 study), medical officer (n = 1 study), and a specialist without further information (n = 1 study). Health students also were involved in the SMES intervention (n = 2 studies). One study proposed the notion of primary care team. Two studies did not give any information on the HCP number and type. A partnership with a community actor was described in 17/68 studies. Some studies reported the implication of the hospital (n = 7 studies), of the patient as partner (n = 5 studies), and of community partners (n = 5 studies; lay community workers, community champion, patient association, advisory panel with community members, community leaders, and village health volunteers).

In 64 studies, the SMES programme was accessible only to the patients and in four studies to both caregivers and patients. The programme mainly focused on one chronic condition (n = 54): diabetes and prediabetes (n = 42), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (n = 5), asthma (n = 3), hypertension (n = 3), and chronic heart failure (n = 1). Among the 14 studies on multimorbidity, the main topics were diabetes and hypertension (n = 6), followed by diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidaemia (n = 1), diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidaemia and nephropathy (n = 1), diabetes and obesity (n = 1), diabetes and mild cognitive impairment (n = 1), heart failure, hypertension and diabetes medication (n = 1), diabetes, cardiovascular disease, COPD, asthma, tobacco, obesity, dyslipidaemia and prediabetes (n = 1), and COPD and another chronic disease (n = 1). One study did not specify the topic. Participants were recruited mainly by the primary care provider (n = 23), by invitation sent to patients identified by searching a health database (n = 12), and by the primary care provider plus identification by health database search (n = 11). The recruitment method was not indicated in twelve studies. In the other ten studies, the recruitment was through secondary care providers, another SMES programme, health insurance, recruitment by investigators or research assistants in the doctor’s waiting area. SMES programmes were mainly at the meso level (n = 31), followed by the micro and macro levels (n = 18 for each). One study did not describe the territory level of the SMES programme (Table 2).

Discussion

Main findings

In this rapid review on SMES programmes in primary care, we collected data on the model dimensions, SMES team composition, and participants. Most studies that referred to a model used a single-dimension organisational model, mainly the CCM. Only three studies described multi-dimension models. In general, the SMES team included two HCPs, mainly nurses. Partnerships with community actors were rarely described. Participants in the programme were mainly patients with one chronic disease. Only 20% of programmes considered multimorbidity.

Comparison with the existing literature

SMES programmes are complex interventions in which several aspects of the healthcare system, HCPs and patients must be taken into account [17]. Our rapid review showed that in order of importance, HCPs consider first the organisational dimension of the SMES practice, and then the learning theory on which the SMES intervention is based. The major place of organisational models indicates that HCPs’ priorities are to better integrate the SMES programme in their daily practice and to take into account their own organisation. Although progress has been made, primary care teams still need to think how to deliver SMES programmes within their organisation [7]. Concerning learning theory-based models, most of them originated from the health and social psychology fields and fewer from the pedagogy field. This lack of educational models underlines the fact that most of the models described in the selected studies focused on understanding and explaining the participants’ behaviour, and not on supporting knowledge acquisition by the participants. This finding may be explained by the fact that for many years, psychology has been an integral part of medical training and is well integrated in the GPs’ practice [141]. Another hypothesis, as underlined by Lorig and Halman, is that this may express a different understanding of what SMES is by the SMES programme developers [142]. Lastly, only three studies included in this review used a multi-dimensional model to structure the SMES programme, by integrating the behavioural, ecological, educational and organisational dimensions. To better integrate SMES programmes in the healthcare system, a multi-dimensional model that takes into account the perspectives of different disciplines is needed. However, this more interdisciplinary approach has not been properly developed and tested yet. The precede-proceed model and the expanded CCM are two examples of multi-dimensional models for SMES implementation that could be considered [20, 70].

Nurses (family nurses, practice nurses, and diabetes nurses) were the main HCP involved in the different SMES programmes. Barreto et al. showed that although all HCPs in the team feel involved in the SMES intervention, nurses are seen by the team as important educators [67]. Similarly, Siminerio et al. reported in a qualitative study that both physicians and nurses agreed that nurses have a better understanding of psychosocial issues and are more likely than physicians to support patients in implementing the SMES programme [143]. These qualitative results were confirmed in the systematic review by Renders et al. showing that a greater involvement of nurses in diabetes management has positive effects on the patients’ outcome [9]. These findings demonstrate the importance of nurses in SMES and the place given to them by the SMES team and healthcare system. In agreement with literature data, we identified very few partnerships with community actors. In their systematic review on SMES, Reynolds et al. found that community resources were implicated in only 0.6% of the included studies [13]. Therefore, the recommendation by Barr et al. in 2003 to enhance community participation is still unmet [20]. This lack of partnerships with community actors in SMES programmes may suggest that HCPs have difficulties in taking ownership of health promotion principles. In 2017, a qualitative study showed that the successful implementation of health promotion principles by primary care providers is influenced by three dimensions: context, implementation process, and collaborative model [144]. Therefore, HCPs should find ways of promoting the integration of community actors in SMES programmes, possibly by integrating health promotion principles in the multidimensional model.

In agreement with the literature, our rapid review showed that SMES interventions in primary care often do not take into account multimorbidity. This is a worrying finding [2, 17]. Some results from previous studies support and promote the development of a multimorbidity approach in primary care. Cameron et al. showed that a moderate-to-severe comorbidity index was the strongest predictor of better self-management (especially maintenance behaviours) by patients [145]. The authors partly explained this result by suggesting that such patients had time to develop skills to cope with their first chronic disease and used this experience for the second chronic condition. Moreover, a multimorbidity model can help HCPs to provide better care. A qualitative study showed how GPs who develop a multimorbidity-focused SMES programme in their practice perceive the benefits of this approach in their care of people with multimorbidity [146]. The necessary collaboration among HCPs for taking care of people with multimorbidity can be facilitated by SMES interventions. However, some difficulties remain in the management of people with multimorbidity. In their systematic review of qualitative studies, Sinnott et al. showed that such difficulties can be classified in four areas: healthcare disorganisation and fragmentation, inadequacy of guidelines and evidence-based medicine, challenges in delivering patient-centred care, and barriers to shared decision making [63]. They also found that for implementing multimorbidity-focused SMES programmes, all healthcare system actors must be implicated and research on multimorbidity must be developed.

Strengths and limitations

Our study has some limitations. First, our rapid review choose to focus only on two databases, although PubMed is one of the main source of publications on health education [30]. Scopus and CINAHL, which also are main databases of articles on health education, were not considered. This choice was necessary due to the rapid increase of publications on SMES interventions for chronic diseases in primary care [13]. This allowed us to thoroughly review the selected papers, despite our small team and time constraints. Second, this rapid review focused on three different aspects of SMES programmes: the model considered by the team, the team performing the SMES programme, and the participants in the programme. Each aspect could have been considered separately, but we wanted to use a global approach. Indeed, many studies showed that a successful SMES programme needs to be thought at multiple levels: health system organisation (HCPs and community partners), patient-clinician interaction (guided by the programme psychological and educational theory), and environmental support (caregivers’ integration) [147]. Third, this review did not focus on the outcomes of the selected studies (biomedical, pedagogical, psychosocial). As SMES programmes are recommended by the main learned societies of chronic disease, we considered that our main objective was to identify models of SMES in primary care [4]. Therefore, we focused on the model of care because according to Kumah et al., it may influence the effects of the SMES programme [11].

One of the strengths of this rapid review is that it brought together researchers with different expertise (education, public health, and primary care). In 2017, Mills et al. identified seven strategic directions that were described in the international chronic condition self-management support framework [148]. One of them was to work with stakeholders from different disciplines for developing programmes, as done by the research team that performed this rapid review.

Conclusion

The increasing number of people with chronic diseases and with multimorbidity stresses the importance of SMES programmes, especially in primary care close to where patients live. Multidimensional models need to be promoted in which nurses and the partnership of community actors play major roles. Better integration of healthcare promotion principles also seems essential to ensure that SMES programmes are better integrated in the community.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset used and analysed in the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CCM:

-

Chronic care model

- CEA:

-

Cost-effectiveness analysis

- CHF:

-

Cardiac heart failure

- CHW:

-

Community health workers

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- DSME:

-

Diabetes self-management education

- GP:

-

General practitioner

- HCP:

-

Health care provider

- HDB:

-

Health database

- MM:

-

Multimorbidity

- Mm:

-

Mixed method

- MMAT:

-

Mixed methods appraisal tools

- NA:

-

Non-applicable

- OECD:

-

Organisation for economic co-operation and development

- PC:

-

Primary care

- PCP:

-

Primary care provider

- PCT:

-

Primary care team

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- QD:

-

Quantitative descriptive

- Ql:

-

Qualitative

- QNR:

-

Quantitative non randomised

- QRCT:

-

Quantitative randomised controlled trials

- RR:

-

Rapid review

- SM:

-

Self-management

- SMES:

-

Self-Management Education and Support

References

Vos T, Lim SS, Abbafati C, Abbas KM, Abbasi M, Abbasifard M, et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet. 2020;396(10258):1204–22.

Hajat C, Stein E. The global burden of multiple chronic conditions: A narrative review. Prev Med Rep. 2018;19(12):284–93.

Steinsbekk A, Rygg LØ, Lisulo M, Rise MB, Fretheim A. Group based diabetes self-management education compared to routine treatment for people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. A systematic review with meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:213.

American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2022 Abridged for Primary Care Providers. Clin Diabetes. 2022;40(1):10–38.

Megari K. Quality of Life in Chronic Disease Patients. Health Psychol Res. 2013;1(3):e27.

Powers MA, Bardsley J, Cypress M, Duker P, Funnell MM, Fischl AH, et al. Diabetes Self-management Education and Support in Type 2 Diabetes: A Joint Position Statement of the American Diabetes Association, the American Association of Diabetes Educators, and the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Clin Diabetes Publ Am Diabetes Assoc. 2016;34(2):70–80.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, editor. Realising the potential of primary health care. Paris: OECD; 2020. p. 205. (OECD health policy studies).

Horigan G, Davies M, Findlay-White F, Chaney D, Coates V. Reasons why patients referred to diabetes education programmes choose not to attend: a systematic review. Diabet Med J Br Diabet Assoc. 2017;34(1):14–26.

Renders CM, Valk GD, Griffin S, Wagner EH, Eijk JT, Assendelft WJ. Interventions to improve the management of diabetes mellitus in primary care, outpatient and community settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;1:CD001481.

Allory E, Lucas H, Maury A, Garlantezec R, Kendir C, Chapron A, et al. Perspectives of deprived patients on diabetes self-management programmes delivered by the local primary care team: a qualitative study on facilitators and barriers for participation, in France. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):855.

Kumah E, Afriyie EK, Abuosi AA, Ankomah SE, Fusheini A, Otchere G. Influence of the Model of Care on the Outcomes of Diabetes Self-Management Education Program: A Scoping Review. J Diabetes Res. 2021;2021:2969243.

Wagner EH. Organizing Care for Patients With Chronic Illness Revisited. Milbank Q. 2019;97(3):659–64.

Reynolds R, Dennis S, Hasan I, Slewa J, Chen W, Tian D, et al. A systematic review of chronic disease management interventions in primary care. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19(1):11.

Rijken M, Bekkema N, Boeckxstaens P, Schellevis FG, De Maeseneer JM, Groenewegen PP. Chronic Disease Management Programmes: an adequate response to patients’ needs? Health Expect Int J Public Particip Health Care Health Policy. 2014;17(5):608–21.

Barlow J, Wright C, Sheasby J, Turner A, Hainsworth J. Self-management approaches for people with chronic conditions: a review. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;48(2):177–87.

Lillyman S, Farquharson N. Self-care management education models in primary care. Br J Community Nurs. 2013;18(11):556–60.

Dineen-Griffin S, Garcia-Cardenas V, Williams K, Benrimoj SI. Helping patients help themselves: A systematic review of self-management support strategies in primary health care practice. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(8):e0220116.

Adan M, Gillies C, Tyrer F, Khunti K. The multimorbidity epidemic: challenges for real-world research. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2020;21:e6.

Longhini J, Canzan F, Mezzalira E, Saiani L, Ambrosi E. Organisational models in primary health care to manage chronic conditions: A scoping review. Health Soc Care Community. 2022;30(3):e565–88.

Barr VJ, Robinson S, Marin-Link B, Underhill L, Dotts A, Ravensdale D, et al. The expanded Chronic Care Model: an integration of concepts and strategies from population health promotion and the Chronic Care Model. Hosp Q. 2003;7(1):73–82.

Gress S, Baan CA, Calnan M, Dedeu T, Groenewegen P, Howson H, et al. Co-ordination and management of chronic conditions in Europe: the role of primary care–position paper of the European Forum for Primary Care. Qual Prim Care. 2009;17(1):75–86.

van den Akker M, Buntinx F, Knottnerus JA. Comorbidity or multimorbidity. Eur J Gen Pract. 1996;2(2):65–70.

Moffat K, Mercer SW. Challenges of managing people with multimorbidity in today’s healthcare systems. BMC Fam Pract. 2015;14(16):129.

Navickas R, Petric VK, Feigl AB, Seychell M. Multimorbidity: What do we know? What should we do? J Comorbidity. 2016;6(1):4–11.

Prazeres F, Santiago L. The Knowledge, Awareness, and Practices of Portuguese General Practitioners Regarding Multimorbidity and its Management: Qualitative Perspectives from Open-Ended Questions. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(11):1097.

Tadeu ACR, e Silva Caetano IRC, de Figueiredo IJ, Santiago LM. Multimorbidity and consultation time: a systematic review. BMC Fam Pract. 2020;21(1):152.

Tricco AC, Langlois EtienneV, Straus SE, Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research, World Health Organization. Rapid reviews to strengthen health policy and systems: a practical guide. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017 [Cited 2022 Jan 26]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/258698.

Tricco AC, Antony J, Zarin W, Strifler L, Ghassemi M, Ivory J, et al. A scoping review of rapid review methods. BMC Med. 2015;16(13):224.

Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;29(372):n160.

Burtis AT, Taylor MK. Mapping the literature of health education: 2006–2008. J Med Libr Assoc JMLA. 2010;98(4):293–9.

Halladay CW, Trikalinos TA, Schmid IT, Schmid CH, Dahabreh IJ. Using data sources beyond PubMed has a modest impact on the results of systematic reviews of therapeutic interventions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68(9):1076–84.

Thompson GN, Estabrooks CA, Degner LF. Clarifying the concepts in knowledge transfer: a literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2006;53(6):691–701.

World Health Organization. WHO consolidated guideline on self-care interventions for health: sexual and reproductive health and rights. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019 [Cited 2023 Nov 23]. Available from: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/325480.

Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3):457–502.

Hong QN, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, Dagenais P, et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ Inf. 2018;34(4):285–91.

Karazivan P, Dumez V, Flora L, Pomey MP, Del Grande C, Ghadiri DP, et al. The patient-as-partner approach in health care: a conceptual framework for a necessary transition. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2015;90(4):437–41.

De Maeseneer J, Aertgeers B, De Lepeleire J, Remmen R, Devroey D. Together we change!. HUISARTS NU. 2015;43:144–5.

Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, Hindmarsh M, Schaefer J, Bonomi A. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2001;20(6):64–78.

Wagner EH, Glasgow RE, Davis C, Bonomi AE, Provost L, McCulloch D, et al. Quality improvement in chronic illness care: a collaborative approach. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 2001;27(2):63–80.

Wagner EH. Chronic disease management: what will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Eff Clin Pract ECP. 1998;1(1):2–4.

Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. JAMA. 2002;288(14):1775–9.

Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: the chronic care model, Part 2. JAMA. 2002;288(15):1909–14.

Coleman K, Austin BT, Brach C, Wagner EH. Evidence on the Chronic Care Model in the new millennium. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2009;28(1):75–85.

Bodenheimer T, Laing BY. The teamlet model of primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5(5):457–61.

Jackson C, Tsai J, Brown C, Askew D, Russell A. GPs with special interests - impacting on complex diabetes care. Aust Fam Physician. 2010;39(12):972–4.

Toledo FGS, Ruppert K, Huber KA, Siminerio LM. Efficacy of the Telemedicine for Reach, Education, Access, and Treatment (TREAT) model for diabetes care. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(8):e179–180.

Joint Principles of the Patient-Centered Medical Home. :3.

Lorig KR, Sobel DS, Ritter PL, Laurent D, Hobbs M. Effect of a self-management program on patients with chronic disease. Eff Clin Pract ECP. 2001;4(6):256–62.

Iora Health. [Cited 2022 Jun 29]. Restoring Humanity to Health Care. Available from: https://www.iorahealth.com/.

Watson LL, Bluml BM. Integrating pharmacists into diverse diabetes care teams: implementation tactics from Project IMPACT: Diabetes. J Am Pharm Assoc JAPhA. 2014;54(5):538–41.

Rollnick S, Miller WR, Butler C. Motivational interviewing in health care: helping patients change behavior. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. p. 210. (Applications of motivational interviewing).

Maindal HT, Kirkevold M, Sandbaek A, Lauritzen T. Lifting the lid of the ‘black intervention box’ - the systematic development of an action competence programme for people with screen-detected dysglycaemia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;7(10):114.

Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot AJHP. 1997;12(1):38–48.

Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC. In Search of the Structure of Change. In: Klar Y, Fisher JD, Chinsky JM, Nadler A, editors. Self Change: Social Psychological and Clinical Perspectives [Internet]. New York, NY: Springer; 1992 [Cited 2022 Jun 21]. p. 87–114. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-2922-3_5.

Bandura A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84(2):191–215.

Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav Off Publ Soc Public Health Educ. 2004;31(2):143–64.

Funnell MM, Nwankwo R, Gillard ML, Anderson RM, Tang TS. Implementing an empowerment-based diabetes self-management education program. Diabetes Educ. 2005;31(1):53 55–5661.

Leventhal H, Phillips LA, Burns E. The Common-Sense Model of Self-Regulation (CSM): a dynamic framework for understanding illness self-management. J Behav Med. 2016;39(6):935–46.

Berglund M. Att ta rodret i sitt liv : Lärande utmaningar vid långvarig sjukdom. 2011 [Cited 2022 Oct 10]; Available from: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:lnu:diva-11536.

Stellefson M, Dipnarine K, Stopka C. The chronic care model and diabetes management in US primary care settings: a systematic review. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E26.

Glasgow RE, Goldstein MG, Ockene JK, Pronk NP. Translating what we have learned into practice. Principles and hypotheses for interventions addressing multiple behaviors in primary care. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(2 Suppl):88–101.

Emmons KM, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing in health care settings. Opportunities and limitations. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20(1):68–74.

Sinnott C, Hugh SM, Browne J, Bradley C. GPs’ perspectives on the management of patients with multimorbidity: systematic review and synthesis of qualitative research. BMJ Open. 2013;3(9):e003610.

Hayden J. Introduction to health behavior theory. 3rd ed. Burlington: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2019. p. 308.

Hettema J, Steele J, Miller WR. Motivational interviewing. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:91–111.

Janz NK, Becker MH. The Health Belief Model: a decade later. Health Educ Q. 1984;11(1):1–47.

Barreto ACO, Rebouças CBdA, de Aguiar MIF, Barbosa RB, Rocha SR, Cordeiro LM, et al. Perception of the Primary Care multiprofessional team on health education. Rev Bras Enferm. 2019;72(suppl 1):266–73.

Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: preparing people for change. New York: Guilford Press; 2002.

Goldstein MG, Whitlock EP, DePue J, Planning Committee of the Addressing Multiple Behavioral Risk Factors in Primary Care Project. Multiple behavioral risk factor interventions in primary care. Summary of research evidence. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(2 Suppl):61–79.

Green LW, Kreuter MW, Green LW. Health program planning: an educational and ecological approach. 4th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2005. p. 1.

Corbin JM, Strauss AL. Unending work and care: managing chronic illness at home. 1st edition. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1988. p. 358. (A Joint publication in the Jossey-Bass health series and the Jossey-Bass social and behavioral science series).

American Pharmacists Association, National Association of Chain Drug Stores Foundation. Medication therapy management in pharmacy practice: core elements of an MTM service model (version 2.0). J Am Pharm Assoc JAPhA. 2008;48(3):341–53.

Kuhmmer R, Lazzaretti RK, Guterres CM, Raimundo FV, Leite LEA, Delabary TS, et al. Effectiveness of multidisciplinary intervention on blood pressure control in primary health care: a randomized clinical trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1):456.

Denford S, Campbell JL, Frost J, Greaves CJ. Processes of change in an asthma self-care intervention. Qual Health Res. 2013;23(10):1419–29.

Adachi M, Yamaoka K, Watanabe M, Nishikawa M, Kobayashi I, Hida E, et al. Effects of lifestyle education program for type 2 diabetes patients in clinics: a cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:467.

DePue JD, Dunsiger S, Seiden AD, Blume J, Rosen RK, Goldstein MG, et al. Nurse-community health worker team improves diabetes care in American Samoa: results of a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(7):1947–53.

Hepworth J, Askew D, Jackson C, Russell A. ‘Working with the team’: an exploratory study of improved type 2 diabetes management in a new model of integrated primary/secondary care. Aust J Prim Health. 2013;19(3):207–12.

Krebs JD, Parry-Strong A, Gamble E, McBain L, Bingham LJ, Dutton ES, et al. A structured, group-based diabetes self-management education (DSME) programme for people, families and whanau with type 2 diabetes (T2DM) in New Zealand: an observational study. Prim Care Diabetes. 2013;7(2):151–8.

Ryan JG, Jennings T, Vittoria I, Fedders M. Short and long-term outcomes from a multisession diabetes education program targeting low-income minority patients: a six-month follow up. Clin Ther. 2013;35(1):A43–53.

Shaw RJ, Kaufman MA, Bosworth HB, Weiner BJ, Zullig LL, Lee SYD, et al. Organizational factors associated with readiness to implement and translate a primary care based telemedicine behavioral program to improve blood pressure control: the HTN-IMPROVE study. Implement Sci IS. 2013;8:106.

Bluml BM, Watson LL, Skelton JB, Manolakis PG, Brock KA. Improving outcomes for diverse populations disproportionately affected by diabetes: final results of Project IMPACT: Diabetes. J Am Pharm Assoc JAPhA. 2014;54(5):477–85.

Brunisholz KD, Briot P, Hamilton S, Joy EA, Lomax M, Barton N, et al. Diabetes self-management education improves quality of care and clinical outcomes determined by a diabetes bundle measure. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2014;7:533–42.

Eakin EG, Winkler EA, Dunstan DW, Healy GN, Owen N, Marshall AM, et al. Living well with diabetes: 24-month outcomes from a randomized trial of telephone-delivered weight loss and physical activity intervention to improve glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(8):2177–85.

Grigg J, Ning Y, Santana C. The impact of certified diabetes educators on diabetes performance and variation among primary care sites within an integrated health system. J Prim Care Community Health. 2014;5(2):80–4.

Ku GMV, Kegels G. Effects of the First Line Diabetes Care (FiLDCare) self-management education and support project on knowledge, attitudes, perceptions, self-management practices and glycaemic control: a quasi-experimental study conducted in the Northern Philippines. BMJ Open. 2014;4(8):e005317.

Liddy C, Johnston S, Nash K, Ward N, Irving H. Health coaching in primary care: a feasibility model for diabetes care. BMC Fam Pract. 2014;15:60.

Maindal HT, Carlsen AH, Lauritzen T, Sandbaek A, Simmons RK. Effect of a participant-driven health education programme in primary care for people with hyperglycaemia detected by screening: 3-year results from the Ready to Act randomized controlled trial (nested within the ADDITION-Denmark study). Diabet Med J Br Diabet Assoc. 2014;31(8):976–86.

Ruggiero L, Riley BB, Hernandez R, Quinn LT, Gerber BS, Castillo A, et al. Medical assistant coaching to support diabetes self-care among low-income racial/ethnic minority populations: randomized controlled trial. West J Nurs Res. 2014;36(9):1052–73.

Siminerio L, Ruppert K, Huber K, Toledo FGS. Telemedicine for Reach, Education, Access, and Treatment (TREAT): linking telemedicine with diabetes self-management education to improve care in rural communities. Diabetes Educ. 2014;40(6):797–805.

Thom DH, Hessler D, Willard-Grace R, Bodenheimer T, Najmabadi A, Araujo C, et al. Does health coaching change patients’ trust in their primary care provider? Patient Educ Couns. 2014;96(1):135–8.

Boland MRS, Kruis AL, Huygens SA, Tsiachristas A, Assendelft WJJ, Gussekloo J, et al. Exploring the variation in implementation of a COPD disease management programme and its impact on health outcomes: a post hoc analysis of the RECODE cluster randomised trial. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2015;25:15071.

Cowden JD, Wilkerson-Amendell S, Weathers L, Gonzalez ED, Dinakar C, Westbrook DH, et al. The talking card: Randomized controlled trial of a novel audio-recording tool for asthma control. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2015;36(5):e86–91.

Edelman D, Dolor RJ, Coffman CJ, Pereira KC, Granger BB, Lindquist JH, et al. Nurse-led behavioral management of diabetes and hypertension in community practices: a randomized trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(5):626–33.

Fort MP, Murillo S, López E, Dengo AL, Alvarado-Molina N, de Beausset I, et al. Impact evaluation of a healthy lifestyle intervention to reduce cardiovascular disease risk in health centers in San José, Costa Rica and Chiapas. Mexico BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:577.

Gucciardi E, Espin S, Morganti A, Dorado L. Implementing Specialized Diabetes Teams in Primary Care in Southern Ontario. Can J Diabetes. 2015;39(6):467–77.

Jiao F, Fung CSC, Wan YF, McGhee SM, Wong CKH, Dai D, et al. Long-term effects of the multidisciplinary risk assessment and management program for patients with diabetes mellitus (RAMP-DM): a population-based cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2015;14:105.

Mash R, Kroukamp R, Gaziano T, Levitt N. Cost-effectiveness of a diabetes group education program delivered by health promoters with a guiding style in underserved communities in Cape Town. South Africa Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(5):622–6.

Mino-León D, Reyes-Morales H, Flores-Hernández S. Effectiveness of involving pharmacists in the process of ambulatory health care to improve drug treatment adherence and disease control. J Eval Clin Pract. 2015;21(1):7–12.

Page TF, Amofah SA, McCann S, Rivo J, Varghese A, James T, et al. Care Management Medical Home Center Model: Preliminary Results of a Patient-Centered Approach to Improving Care Quality for Diabetic Patients. Health Promot Pract. 2015;16(4):609–16.

Sepers CEJ, Fawcett SB, Lipman R, Schultz J, Colie-Akers V, Perez A. Measuring the Implementation and Effects of a Coordinated Care Model Featuring Diabetes Self-management Education Within Four Patient-Centered Medical Homes. Diabetes Educ. 2015;41(3):328–42.

Willard-Grace R, Chen EH, Hessler D, DeVore D, Prado C, Bodenheimer T, et al. Health coaching by medical assistants to improve control of diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia in low-income patients: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(2):130–8.

Wong CKH, Wong WCW, Wan EYF, Wong WHT, Chan FWK, Lam CLK. Increased number of structured diabetes education attendance was not associated with the improvement in patient-reported health-related quality of life: results from Patient Empowerment Programme (PEP). Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13:126.

Zhong X, Wang Z, Fisher EB, Tanasugarn C. Peer Support for Diabetes Management in Primary Care and Community Settings in Anhui Province. China Ann Fam Med. 2015;13:S50–58.

Chomko ME, Odegard PS, Evert AB. Enhancing Access to Diabetes Self-management Education in Primary Care. Diabetes Educ. 2016;42(5):635–45.

Kane EP, Collinsworth AW, Schmidt KL, Brown RM, Snead CA, Barnes SA, et al. Improving diabetes care and outcomes with community health workers. Fam Pract. 2016;33(5):523–8.

Loskutova NY, Tsai AG, Fisher EB, LaCruz DM, Cherrington AL, Harrington TM, et al. Patient Navigators Connecting Patients to Community Resources to Improve Diabetes Outcomes. J Am Board Fam Med JABFM. 2016;29(1):78–89.

Odnoletkova I, Ramaekers D, Nobels F, Goderis G, Aertgeerts B, Annemans L. Delivering Diabetes Education through Nurse-Led Telecoaching. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis PloS One. 2016;11(10):e0163997.

Ramli AS, Selvarajah S, Daud MH, Haniff J, Abdul-Razak S, Tg-Abu-Bakar-Sidik TMI, et al. Effectiveness of the EMPOWER-PAR Intervention in Improving Clinical Outcomes of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in Primary Care: A Pragmatic Cluster Randomised Controlled Trial. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17(1):157.

Murray E, Sweeting M, Dack C, Pal K, Modrow K, Hudda M, et al. Web-based self-management support for people with type 2 diabetes (HeLP-Diabetes): randomised controlled trial in English primary care. BMJ Open. 2017;7(9):e016009.

Rodis JL, Sevin A, Awad MH, Porter B, Glasgow K, Hornbeck Fox C, et al. Improving Chronic Disease Outcomes Through Medication Therapy Management in Federally Qualified Health Centers. J Prim Care Community Health. 2017;8(4):324–31.

Weldam SWM, Schuurmans MJ, Zanen P, Heijmans MJWM, Sachs APE, Lammers JWJ. The effectiveness of a nurse-led illness perception intervention in COPD patients: a cluster randomised trial in primary care. ERJ Open Res. 2017;3(4):00115–2016.

Yeung DL, Alvarez KS, Quinones ME, Clark CA, Oliver GH, Alvarez CA, et al. Low–health literacy flashcards & mobile video reinforcement to improve medication adherence in patients on oral diabetes, heart failure, and hypertension medications. J Am Pharm Assoc JAPhA. 2017;57(1):30–7.

Benedict AW, Spence MM, Sie JL, Chin HA, Ngo CD, Salmingo JF, et al. Evaluation of a Pharmacist-Managed Diabetes Program in a Primary Care Setting Within an Integrated Health Care System. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2018;24(2):114–22.

Bourbeau J, Farias R, Li PZ, Gauthier G, Battisti L, Chabot V, et al. The Quebec Respiratory Health Education Network: Integrating a model of self-management education in COPD primary care. Chron Respir Dis. 2018;15(2):103–13.

Coultas DB, Jackson BE, Russo R, Peoples J, Singh KP, Sloan J, et al. Home-based Physical Activity Coaching, Physical Activity, and Health Care Utilization in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Self-Management Activation Research Trial Secondary Outcomes. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15(4):470–8.

Piatt GA, Rodgers EA, Xue L, Zgibor JC. Integration and Utilization of Peer Leaders for Diabetes Self-Management Support: Results From Project SEED (Support, Education, and Evaluation in Diabetes). Diabetes Educ. 2018;44(4):373–82.

Torres HdC, Pace AE, Chaves FF, Velasquez-Melendez G, Reis IA. Evaluation of the effects of a diabetes educational program: a randomized clinical trial. Rev Saude Publica. 2018;52:8.

Aekplakorn W, Tantayotai V, Numsangkul S, Tatsato N, Luckanajantachote P, Himathongkam T. Evaluation of a Community-Based Diabetes Prevention Program in Thailand: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. J Prim Care Community Health. 2019;10:2150132719847374.

Contant É, Loignon C, Bouhali T, Almirall J, Fortin M. A multidisciplinary self-management intervention among patients with multimorbidity and the impact of socioeconomic factors on results. BMC Fam Pract. 2019;20(1):53.

Francesconi P, Ballo P, Profili F, Policardo L, Roti L, Zuppiroli A. Chronic Care Model for the Management of Patients with Heart Failure in Primary Care. Health Serv Insights. 2019;12:1178632919866200.

Moreno PI, Ramirez AG, San Miguel-Majors SL, Fox RS, Castillo L, Gallion KJ, et al. Satisfaction with cancer care, self-efficacy, and health-related quality of life in Latino cancer survivors. Cancer. 2018;124(8):1770–9.

Shah V, Stokes J, Sutton M. Effects of non-medical health coaching on multimorbid patients in primary care: a difference-in-differences analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):593.

Siminerio L, Hamm M, Kanter J, Cameron FdA, Krall J. A Diabetes Education Model in Primary Care: Provider and Staff Perspectives. Diabetes Educ. 2019;45(5):498–506.

Srulovici E, Leventer-Roberts M, Curtis B, He X, Hoshen M, Rotem M, et al. Effectiveness of Managing Diabetes During Ramadan Conversation Map intervention: A difference-in-differences (self-comparison) design. Int J Nurs Stud. 2019;95:65–72.

van Puffelen AL, Heijmans MJ, Schellevis FG, Nijpels G, Rijken M. Improving self-management of people with type 2 diabetes in the first years after diagnosis: Development and pilot of a theory-based interactive group intervention. SAGE Open Med. 2019;7:2050312119847918.

Zupa MF, Arena VC, Johnson PA, Thearle MB, Siminerio LM. A Coordinated Population Health Approach to Diabetes Education in Primary Care. Diabetes Educ. 2019;45(6):580–5.

Ansari S, Hosseinzadeh H, Dennis S, Zwar N. Activating primary care COPD patients with multi-morbidity through tailored self-management support. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2020;30(1):12.

Kjellsdotter A, Berglund M, Jebens E, Kvick J, Andersson S. To take charge of one’s life - group-based education for patients with type 2 diabetes in primary care - a lifeworld approach. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-Being. 2020;15(1):1726856.

Mammen JR, Schoonmaker JD, Java J, Halterman J, Berliant MN, Crowley A, et al. Going mobile with primary care: smartphone-telemedicine for asthma management in young urban adults (TEAMS). J Asthma. 2022;59(1):132–44.

Rovner BW, Casten RJ, Piersol CV, White N, Kelley M, Leiby BE. Improving Glycemic Control in African Americans With Diabetes and Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(5):1015–22.

Saude J, Baker ML, Axman LM, Swider SM. Applying the Chronic Care Model to Improve Patient Activation at a Nurse-Managed Student-Run Free Clinic for Medically Underserved People. SAGE Open Nurs. 2020;6:2377960820902612.

Vitale M, Xu C, Lou W, Horodezny S, Dorado L, Sidani S, et al. Impact of diabetes education teams in primary care on processes of care indicators. Prim Care Diabetes. 2020;14(2):111–8.

Willard-Grace R, Chirinos C, Wolf J, DeVore D, Huang B, Hessler D, et al. Lay Health Coaching to Increase Appropriate Inhaler Use in COPD: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Fam Med. 2020;18(1):5–14.

Alibrahim A, AlRamadhan D, Johny S, Alhashemi M, Alduwaisan H, Al-Hilal M. The effect of structured diabetes self-management education on type 2 diabetes patients attending a Primary Health Center in Kuwait. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2021;171:108567.

Batch BC, Spratt SE, Blalock DV, Benditz C, Weiss A, Dolor RJ, et al. General Behavioral Engagement and Changes in Clinical and Cognitive Outcomes of Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Using the Time2Focus Mobile App for Diabetes Education: Pilot Evaluation. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(1):e17537.

Represas-Carrera F, S CV, F ML, B M, R MB, JI RR, et al. Effectiveness of a Multicomponent Intervention in Primary Care That Addresses Patients with Diabetes Mellitus with Two or More Unhealthy Habits, Such as Diet, Physical Activity or Smoking: Multicenter Randomized Cluster Trial (EIRA Study). Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(11). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34071171/.

Talavera, SF C, PM M, M LG, S R, MS P, et al. Latinos understanding the need for adherence in diabetes (LUNA-D): a randomized controlled trial of an integrated team-based care intervention among Latinos with diabetes. Transl Behav Med. 2021;11(9):1665–75.

Moriyama M, K K, Y J, M I, M M, Y F, et al. The Effectiveness of Telenursing for Self-Management Education on Cardiometabolic Conditions: A Pilot Project on a Remote Island of Ōsakikamijima Japan. J Prim Care Community Health. 2021;12:21501327211030816.

Fu S, MC D, CKH W, BMY C. Knowledge and practice of home blood pressure monitoring 6 months after the risk and assessment management programme: does health literacy matter? Postgrad Med J. 2021; Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34039693/.

Veldheer S, C S, CR B, C O, B W, L W, et al. Impact of a Prescription Produce Program on Diabetes and Cardiovascular Risk Outcomes. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2021;53(12):1008–17.

Robiner WN, Hong BA, Ward W. Psychologists’ Contributions to Medical Education and Interprofessional Education in Medical Schools. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2021;28(4):666–78.

Lorig KR, Holman H. Self-management education: history, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med Publ Soc Behav Med. 2003;26(1):1–7.

Siminerio LM, Funnell MM, Peyrot M, Rubin RR. US nurses’ perceptions of their role in diabetes care: results of the cross-national Diabetes Attitudes Wishes and Needs (DAWN) study. Diabetes Educ. 2007;33(1):152–62.

Martinez C, Bacigalupe G, Cortada JM, Grandes G, Sanchez A, Pombo H, et al. The implementation of health promotion in primary and community care: a qualitative analysis of the ‘Prescribe Vida Saludable’ strategy. BMC Fam Pract. 2017;18(1):23.

Cameron J, Worrall-Carter L, Riegel B, Lo SK, Stewart S. Testing a model of patient characteristics, psychologic status, and cognitive function as predictors of self-care in persons with chronic heart failure. Heart Lung. 2009;38(5):410–8.

Richter S, Demirer I, Nocon M, Pfaff H, Karbach U. When do physicians perceive the success of a new care model differently? BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):1058.

Glasgow RE, Davis CL, Funnell MM, Beck A. Implementing practical interventions to support chronic illness self-management. Jt Comm J Qual Saf. 2003;29(11):563–74.

Mills SL, Brady TJ, Jayanthan J, Ziabakhsh S, Sargious PM. Toward consensus on self-management support: the international chronic condition self-management support framework. Health Promot Int. 2017;32(6):942–52.

Acknowledgements

We thank the French network of University Hospitals HUGO (‘Hôpitaux Universitaires du Grand Ouest’) who supported this article and Candan Kendir for critical reading of the manuscript.

Funding

No specific funding for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EA and JS independently assessed studies for eligibility, extracted data, and assessed the study quality. In case of conflict in the evaluation of the full-text, conflict was solved with the intervention of RGy. VdA, RGz and RGy provided methodological and statistical support to the analysis. All authors contributed to the drafting of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

PRISMA 2020 checklist.

Additional file 2.

PRISMA 2020 for Abstracts Checklist.

Additional file 3.

Results of the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tools (MMAT) evaluation (1).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Allory, E., Scheer, J., De Andrade, V. et al. Characteristics of self-management education and support programmes for people with chronic diseases delivered by primary care teams: a rapid review. BMC Prim. Care 25, 46 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-024-02262-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-024-02262-2