Abstract

Background

Improving access to primary health care is among top priorities for many countries. Advanced Access (AA) is one of the most recommended models to improve timely access to care. Over the past 15 years, the AA model has been implemented in Canada, but the implementation of AA varies substantially among providers and clinics. Continuous quality improvement (CQI) approaches can be used to promote organizational change like AA implementation. While CQI fosters the adoption of evidence-based practices, knowledge gaps remain, about the mechanisms by which QI happens and the sustainability of the results. The general aim of the study is to analyse the implementation and effects of CQI cohorts on AA for primary care clinics. Specific objectives are: 1) Analyse the process of implementing CQI cohorts to support PHC clinics in their improvement of AA. 2) Document and compare structural organisational changes and processes of care with respect to AA within study groups (intervention and control). 3) Assess the effectiveness of CQI cohorts on AA outcomes. 4) Appreciate the sustainability of the intervention for AA processes, organisational changes and outcomes.

Methods

Cluster-controlled trial allowing for a comprehensive and rigorous evaluation of the proposed intervention 48 multidisciplinary primary care clinics will be recruited to participate. 24 Clinics from the intervention regions will receive the CQI intervention for 18 months including three activities carried out iteratively until the clinic’s improvement objectives are achieved: 1) reflective sessions and problem priorisation; 2) plan-do-study-act cycles; and 3) group mentoring. Clinics located in the control regions will receive an audit-feedback report on access. Complementary qualitative and quantitative data reflecting the quintuple aim will be collected over a period of 36 months.

Results

This research will contribute to filling the gap in the generalizability of CQI interventions and accelerate the spread of effective AA improvement strategies while strengthening local QI culture within clinics. This research will have a direct impact on patients’ experiences of care.

Conclusion

This mixed-method approach offers a unique opportunity to contribute to the scientific literature on large-scale CQI cohorts to improve AA in primary care teams and to better understand the processes of CQI.

Trial registration

Clinical Trials: NCT05715151.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Timely access in primary healthcare

Access is one of the major concerns faced by health systems worldwide. Access to health services is a high priority for the population, clinicians and decision-makers alike [1]. Timely access, such that patients can access the care they need when they need it, is one of the cornerstones of strong primary healthcare (PHC). Across Canada, timely access remains a major challenge. A recent international report documenting primary care access found that Canada ranks poorly compared to other high-income countries. According to a 2020 report by the Commonwealth Fund, only 41% of Canadians reported being able to get a same or next day appointment to see a doctor or a nurse the last time they needed medical attention [2]. This is a 5% decline since the previous report in 2016 [2]. Limited access increases the risk of poor health outcomes and health disparities [3, 4] and increases costs for the healthcare system.

Advanced Access as a solution to improve access and continuity of care

Of the various organisational innovations developed to improve timely access to care, Advanced Access (AA) is one of the most recommended models [5]. Rooted in patients’ relational and informational continuity with a PHC professional/team to increase accessibility, the AA model ensures that patients obtain timely services based on their needs [6]. Originally developed in the United States in 2001, the effectiveness of the AA model, practiced among physicians and nurses, has been demonstrated in various healthcare systems [7,8,9,10,11]. Benefits of AA include reduced wait times [7, 9, 11,12,13] and missed appointments [7, 13] and improved professional and patient satisfaction [11, 14] as well as provider productivity [11].

Over the last two decades, AA has become increasingly popular in Canada. The model has been widely promoted by the College of Family Physicians of Canada and several other provincial organisations and professional associations [6]. Since the inception of the AA model 20 years ago, our research team has developed a revised model based on a more interdisciplinary team practice through a process of multiple consultations with 45 experts. The revised model is based on five key pillars: 1) comprehensive planning for needs, supply and recurring variations; 2) regular adjustment of supply to demand; 3) processes of appointment booking and scheduling; 4) integration and optimisation of collaborative practice; and 5) communication about AA and its functionalities [15]. The Fig. 1 presented the revised Advanced Access model.

Over the past years, the AA model has been implemented in Canada to varying degrees. On a more local level, the implementation of AA varies quite a lot among both providers and clinics [16, 17]. More importantly, our experience in the field shows that the model has not kept up with the development of PHC team-based approaches or with technological innovations [18]. Indeed, very few other PHC providers, such as social workers, psychologists and pharmacists, have implemented the model, despite its interprofessional scope. With the exception of an ongoing proof of concept led by our research team [19], the literature is scarce on strategies to expand the AA model to the entire PHC team.

Continuous quality improvement (CQI) approaches

CQI approaches promote organisational change and are often based on improving specific processes, either by eliminating waste from the system (e.g. LEAN) or reducing variability and errors in the process (e.g. Six-Sigma). A widely used approach, the Model for Improvement [20], is designed to promote, structure and sustain changes in organisations to improve both processes and outcomes [21]. It aims to better understand the system itself, such as cultural or structural changes within the organisation, in order to implement a new model or new processes [22]. Following an investigation of a given problem, changes are implemented through iterative implementation cycles of four steps (represented by the acronym PDSA), [20] where change is: 1) planned based on evidence from data, community feedback and/or stakeholder experience (Plan); 2) carried out while documenting its effects (Do); 3) analysed by measuring the results achieved while comparing them to expected results and appreciating the impact of change (Study); and finally 4) refined, either by maintaining or adjusting actions in future cycles or by expanding its scale (Act).

Factors and techniques for successful CQI

While CQI fosters the adoption of evidence-based practices [20] and is instrumental to achieve the quintuple aim, multiple strategies have been used to support organisational change [23, 24]. Despite emerging evidence on the influence of the implementation context on the outcomes of CQI [25, 26], such as managerial involvement [27], staff attitudes [27,28,29], interprofessional collaboration [28], effective communication [28], the presence of an internal champion [27], available resources [28], general QI culture [30], the absence of conflict [27], the QI objective itself [30] and fit with the organisation’s priorities [30], knowledge gaps remain, especially about the ideal team size and composition, optimal levels of patient involvement [31,32,33], and more importantly, the mechanisms [34,35,36] by which QI happens.

Continuing education alone or combined with other strategies cannot optimally achieve change without intensive follow-up [37, 38]. Experts internal or external to the organisation must accompany the process. This is called practice facilitation [37]. Practice facilitation is especially useful as a stand-alone intervention, compared to more limited strategies such as academic detailing or audit and feedback [37, 39]. Although practice facilitation can also be used effectively in combination with other strategies, studies have shown that tailoring facilitation interventions to the individual is a determining factor to achieve buy-in from stakeholders and, more generally, to implement changes in local settings [40,41,42,43]. Using external change agents in the practice facilitation model also appears to strongly facilitate organisational change, especially for smaller settings and PHC services [40,41,42,43]. Other enablers of practice facilitation include sustained interactions between facilitators and practices, appropriate and regular frequency of practice facilitation [44, 45] and patient and partner engagement [40,41,42,43]. In addition, support and coaching through multiple cycles [46] over a sufficient length of time (12–18 months) [47] are key to complete improvement cycles and achieve change goals [48].

Beyond practice facilitation, the scientific literature offers poor guidance on the criteria to select appropriate strategies to improve the process of CQI [49, 50]. This is largely due to the fact that such processes are often poorly defined in empirical studies and rarely or inadequately evaluated [36, 51,52,53]. This leaves implementers looking to design successful CQI initiatives with vague recommendations on the importance of supporting clinical teams over time through a personalised and evolutive approach focused on relationship building [36]. It is therefore complex to determine with certainty the causal links between CQI processes and their effects.

Studies showing the effectiveness of CQI also highlight its barriers, namely the complexity of healthcare organisations [25], the absence of structure or resources [25, 54, 55], poor understanding (and use) of CQI components [56] or support that is too succinct [25, 47]. Above all, successful CQI is time-consuming and resource intensive [57, 58]. Group mentoring, defined as ongoing group activities where participants with different levels of experience working in similar fields share their experience, increase their skills and take part in opportunities to reflect on their own practice [59], could accelerate PDSA cycles. This rapid knowledge transfer strategy could contribute to increasing the scale for tests of change and, consequently, the spread of successful implementation strategies [60]. In particular, sharing the optimal sequencing of tasks can help other teams plan their change strategies by building on what works or does not work in other teams [20]. Group mentoring through CQI cohorts could reduce isolation, bring new energy to QI strategies and improve knowledge about what works and what does not [61, 62].

Finally, studies focusing primarily on the sustainability of complex innovations supported through CQI are lacking [63, 64]. The few studies available underline the importance of focusing on the sustainability of the process up front, [65] adaptability of the CQI initiative [66] and relevance of the initiative for the organisation [66]. Identifying processes leading to long-term impacts of CQI is key to develop practical guidelines for healthcare teams who wish to improve patient care.

Preliminary work: AA and CQI

Between 2008 and 2010, an Ontario-based CQI learning collaborative program (called QIIP) was available to all Family Health Teams, with some teams focusing, among other themes, on the improvement of their practice in AA. QIIP included three 2-day face-to-face learning sessions, action periods and a summative congress [67] offered in three waves occurring over about 15 months. The program failed to show significant differences between the intervention and control groups for most indicators, including the 3rd next available appointment [67]. Qualitative data suggested significant improvements in some practices, but also a high degree of variability among clinics. Of note, QIIP was successful in facilitating interdisciplinary team functioning. The QIIP team concluded that there was a need for further direct evaluation of QI approaches to improve AA in the future [67, 68].

The Quebec team members have developed extensive expertise and experience in assessing the implementation of AA among different PHC providers [69] and support individual reflection through the use of an online reflexive tool and a rigorous CQI process [19]. This intervention has shown an average decrease of 7 days to the 3rd next appointment and a decrease of 11% on the proportion of available time slots within the next 48 h. This project shed light on the fact that strategies to improve AA are often common across PHC teams and that there is a loss of efficiency when each provider and team are supported individually. Thus, we hypothesise that the addition of group mentoring would allow for system gains by allowing teams of providers 1) to have access to the strategies and learnings of other teams that have experienced it and 2) to share in real time with teams experiencing similar challenges.

There is great potential to improve access in PHC by supporting practices interested in improving AA and by expanding the implementation of the model to professionals other than physicians and nurses. The various AA projects conducted so far have 1) shown promising results and 2) contributed to the development of expertise and several tools to assess and guide the implementation of AA for all types of PHC providers. These findings guided our research team in the development and evaluation of a CQI cohort of PHC practices for the improvement of AA.

Research objectives

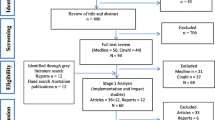

We propose a multi-method quasi-randomised cluster trial to analyse the implementation and effects of CQI cohorts on AA for PHC clinics (see Fig. 2). Specific objectives are to:

-

1.

Analyse the process of implementing CQI cohorts to support PHC clinics in their improvement of AA.

-

2.

Document and compare structural organisational changes and processes of care with respect to AA within study groups (intervention and control).

-

3.

Assess the effectiveness of CQI cohorts on AA outcomes.

-

4.

Appreciate the sustainability of the intervention for AA processes, organisational changes and outcomes.

Conceptual framework

The Informing Quality Improvement Research (InQuIRe) framework was chosen to guide this study [70, 71]. This framework is based on a literature synthesis of CQI theories and themes that have been adapted for PHC. The InQuIRe framework outlines (1) contextual factors at the organisational, team and individual levels; (2) the CQI process, including QI methods and teamwork; and (3) outcomes related to structural changes to organisations or processes of care and quality of care. Our hypothesis is that the proposed intervention will have a long-term impact on various AA processes, outcomes and organisational changes and that those will be influenced by contextual factors. The Fig. 2 shows the conceptual framework and the research objectives of the study.

Methods

Based on the findings of other large-scale CQI initiatives [72], this study will be based on a quasi-randomised cluster-controlled trial allowing for a comprehensive and rigorous evaluation of the proposed intervention [73]. Such a design has been used to better understand both processes and outcomes of CQI [51]. Within the province of Quebec, clinics from randomly selected health regions will receive the intervention, while others will serve as controls (no CQI intervention). Intervention clinics will be matched with control clinics. The matching will be based on the clinic level (1 to 10, based on the number of patients registered and services offered) [74]. Clinics in the control group will receive an audit on a selection of AA indicators (Table 1) and will be offered the intervention 12 to 18 months following their recruitment.

The proposed CQI intervention present in Fig. 3 consists of three activities carried out iteratively until the improvement objectives are achieved or up to a maximum of 18 months of intervention: 1) team reflection and prioritisation of change needs; 2) PDSA cycles; and 3) group mentoring.

Activity 1: reflective sessions and problem prioritisation

An essential condition for people to become involved in improvement initiatives is that they arrive at a shared understanding of the issues to be solved or the challenges to be overcome, which requires a strong commitment from the participants [20, 75,76,77]. Participants in the CQI intervention need to understand the problem and its root causes and contributing factors [58]. To this end, we will organise clinic-wide meetings labeled reflective sessions. These face-to-face sessions, led by the research team and a QI coach, will involve all team members at a given clinic, including clinical, administrative and management staff. During these sessions, we will identify and prioritise AA-related issues. To do so, a summary of AA processes and outcomes will be presented to the group. These will be populated with a comprehensive assessment of both AA processes (using ORAA questionnaires [18]) and outcomes (from the clinic’s electronic medical record [EMR] data and patient-reported experiences of access; see Data collection section below). Through customised facilitation activities, participants will be asked to generate and prioritise ideas to improve AA while considering the concerns of all team members. These activities will maximise engagement of team members and foster discussions and collaboration among them. Examples of facilitated activities include brainstorming sessions, design thinking sessions, root-to-cause analysis and any other activities that might address the specific AA-related issues faced by the team [78]. The end result of Activity 1 consists of an improvement aim [79] focused on a particular AA pillar, identifying the goal(s) the team would like to achieve before the next reflective session, who will benefit from this improvement, how change will be measured and by when.

Activity 2: PDSA cycles

Following the reflective sessions, we will identify a QI team from each clinic, comprised of at least one team member from all categories of staff (e.g. physicians, nurses, administrative staff, other PHC providers, patients) for a maximum of 5–8 individuals. Each member of the QI team will have the responsibility, through PDSA cycles, to reach the aim(s) determined during Activity 1. Supported by the lead research team, they will convene (every 2 to 4 weeks for approximately 30 min) to review the clinic’s aims (first meeting), then develop (Plan) and implement changes (Do), monitor the effect of these changes on key AA measures (Study) and review the process in order to maintain changes or adjust future actions (Act) [80, 81]. These meetings will take place virtually. More frequent meetings will be organised as needed if the pace of the cycles requires it.

Activity 3: group mentoring

As teams engage in PDSA cycles, they will test change strategies and generate knowledge about strategies that do or do not work in their specific context [20]. This knowledge will be documented in change packages that include a clear description of the strategy, the indicators used to evaluate its impact, lessons learned and a sustainability plan [60]. These packages have been reported as being highly valuable in supporting organisational change [63, 82]. Group mentoring will aim to increase the effectiveness of the QI coach’s follow-ups and to optimise knowledge transfer of AA improvement strategies among clinics. The first part of the meetings will consist of continued education material about AA- and CQI-related theories and will be provided by the three QI coaches recruited for the trial. Then, participants will split into groups based on their respective AA pillars of focus. A member of each QI team will be invited to share their learnings from the ongoing PSDA cycles (change strategies adopted, lessons learned, indicators used, data extraction algorithms from the EMR). These exchanges will help improve the change packages for each of the AA pillars. These virtual meetings will be held every 6–8 weeks.

Once an improvement aim has been achieved (expected after 3–9 months), the PHC clinic members will reconvene for another reflective session. The QI team will present the changes implemented during the cycles. These sessions will provide a regular meeting place for all team members to voice their concerns and ideas, which can then be used by the QI team during subsequent PDSA cycles. Depending on their new improvement aim (and associated pillar), the QI team will be invited to join an ongoing mentoring group or to form a new one.

Recruitment

Forty-eight multidisciplinary PHC clinics will be recruited in close collaboration with our key stakeholders using voluntarism and purposeful sampling, with the objective of covering a wide range of organisational structures and contexts, including geographical and socioeconomic differences. To be recruited, clinics must offer interprofessional care (beyond the physician-nurse only model) that is physically located under the same roof. To take part of the study, team member should sign the electronic inform consent form, and at for the PHC clinics at least 50% of all team members should accept to take part in the study to be eligible.

Sample size justification

The Quebec CQI pilot project showed that the average time to the 3rd next available appointment (primary outcome) is 11 days (sd = 10). Forty-eight clinics (clusters) averaging 15 professionals per clinic for a total of 720 professionals over six measurement time points will be measured every week or month (depending on the measure). An assumed intracluster correlation (ICC) of 0.364 (from the pilot project) provides about 80% power to detect a small effect size of 0.25 (Cohen’s d, assuming that variation will increase over the course of the intervention). This translates into a 50% reduction in time to the 3rd next available appointment from the baseline assessment [83]. Variations in clinic size have been considered (coefficient of variation of 0.49 according to the pilot project) [84]. No inflation for loss to follow-up is planned because the data is readily obtained from the EMR system for all professionals. Provision for one interim analysis 12-months post recruitment is planned using the Demets and Lan’s alpha spending function approach [85]. Thus, we aim to recruit 48 PHC clinics (24 interventions and 24 controls) for the trial proposed in this study.

Data collection

Complementary qualitative and quantitative data will be collected over a period of 24 months. To evaluate the proposed trial objectives, data collection will be extended by 12 months in the intervention group only. We will collect data from all clinics in the intervention group for at least 3 months prior to the start of the intervention.

Quantitative component

Organisational, teamwork and individual context

To document contextual factors (Obj. 1 & 3), the organisational context of the clinic will be assessed using the complete Model Maturity Matrix and the Model for Understanding Success in Quality (MUSIQ) based on the observations of the research team with the collaboration of the clinic’s manager [86, 87]. Then, a self-reported survey composed of a total of 45 items adapted from several questionnaires will be used. Teamwork context will be assessed using the mean score of the Team Climate Inventory short-form (TCI) (19 items) [88, 89]. Job satisfaction will be measured using the Mini Z Burnout Survey (10 items) [90, 91]. Work engagement (3 items) will be measured using the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ) [92]. Team composition will be expressed by the number and types of providers working at the clinic, and team stability will be measured by the length of time each team member has been in the clinic as well as the stability of the team throughout the length of the project. To assess the individual context, the Improvement Readiness scale of the SCORE survey [93, 94] (5 items) as well as the agree subscale of the Quality improvement commitment instrument (8 items) will be used [95, 96]. The overall questionnaire should take around 10 to 15 min to complete.

AA structural change & processes (Obj. 2)

Each team member will complete the “Outil Réflexif Accès Adapté” (ORAA) questionnaire, which provides a comprehensive portrait of the participant’s adherence to each AA pillar [18]. Two versions of the questionnaire are available online in both French and English, one for PHC providers (39 items) and one for administrative staff (25 items), and take approximately 12 min and 6 min to complete, respectively. Each respondent is given a unique identifier to ensure confidentiality through a double validation process. Upon completing the questionnaire, respondents receive a personalised report and suggestions to improve their AA practice. Modifications to AA change packages will also be thoroughly documented as the project evolves.

AA Outcomes

Six key AA measures (see Table 1) will be extracted on a weekly or monthly basis via the EMR (Obj. 3). This has been accomplished with great success by the Quebec team over the last two years. Most of these indicators have been used in previous Quebec CQI initiatives on AA. These outcomes will be used to evaluate the effectiveness of the intervention and inform the PDSA cycles (among other indicators chosen by the clinics to document their PDSA cycles). We have successfully automated extraction of the six indicators from an EMR in Quebec. A scale-up process to the other EMRs is ongoing and will be finalised upon trial launch.

To assess effectiveness from patients’ perspectives (Obj. 3), patient-reported experiences will be assessed at each clinic using a 50-item online survey. The questionnaire has been developed based on comparable tools [80, 97,98,99,100] and recommendations from our patient committee. The 50 items cover various dimensions of access from a patient perspective, such as the appointment process, communication and team collaboration. The survey is available in French and English and takes approximately 11 min to complete. An electronic informed consent form precedes the survey. The survey will be distributed electronically to all registered patients for whom an email address is available (estimated between 40 and 80% depending on the clinic). This data collection strategy is inexpensive and includes friendly reminders. Both the questionnaire and distribution mode has been tested with success by the Quebec research team. Cognitive testing [101] has been used with eight patients to validate the tool.

Qualitative component

Document analysis and non-participant observations [102,103,104] will be collected to document and compare structural organisational changes and processes of care with respect to AA (Obj. 2). All documents produced by the teams (e.g. PDSA cycle journaling, change packages) and all meeting minutes related to the three activities of the intervention will be summarised per clinic by the QI coaches using a coding grid. In addition, a logbook will be completed each week to document completed tasks and time spent on them. Every 3 months, QI coaches will evaluate the progress of each clinic for which they are responsible using the Assessment Scale for Collaboratives [105].

At the end of the intervention (T18), as well as 12 months after the intervention (T30), we will conduct focus groups with purposefully selected members of the QI teams to document their ongoing perspectives on CQI processes, their appreciation of CQI methods and the perceived impact on their practice (Obj. 1). Implementation issues and the need for additional training or educational tools will be discussed. With the intervention group, we plan to conduct an average of 10–12 interviews at three times (T12, T18, T30) to better understand the level of appreciation for QI and barriers and facilitators to engaging in QI activities. We will interview a variety of professions and roles within the clinic to ensure information-rich discussions [106].

Data analyses

For the first objective, the analysis will be based on the InQuIRe framework (Fig. 2). Audio recordings and transcripts of interviews will be reviewed simultaneously, to assess validity of the transcription process, and analysed using an iterative approach [107, 108]. Thus, the analysis process will progress as follows throughout data collection for each site: 1) development of a mixed deductive-inductive classification grid; 2) coding according to the classification grid of an initial interview; 3) discussion and team consensus on the final grid; 4) linking of the various emerging themes; 5) coding of all interviews; and 6) validation by two judges (counter-coding) of at least 20% of the material in order to validate the classification. Data saturation will be determined as defined by Constantinou et al. [109] This will be followed by an inter-site analysis to identify commonalities between and specificities of the sites examined [110] and to compare the different configurations between sites [111]. Data will be analysed by wave first. Finally, matrices based on waves will be generated to identify particular intra- and inter-wave patterns [112].

Strategies used to instill structural changes in the organisation and processes of care (Obj. 2) will be rigorously documented and categorised by AA pillar. During PDSA cycles of a given strategy, its efficacy within each clinic will be assessed using run charts [113] and control charts [114] and their respective rules of interpretation. In addition to distinguishing systematic changes from chance variation [115], these types of graphs will allow for monitoring of the performance of the strategy developed by the clinics to improve AA and inform the PDSA cycles (Activity 2 of the intervention).

The impact of the intervention on AA outcomes (Obj. 3) will be structured around the quintuple aim [116]. For all outcomes, we will describe clinics and participants using means and standard deviations or medians and interquartile ranges. Also, time series analyses will be performed based on EMR indicators to detect changes since baseline, at the beginning of the intervention (T3), during the intervention (T3–T18) and the sustainability of the changes (T30). Care team functioning: To account for clustering of providers within clinics, the primary outcome measure, 3rd next available appointment, will be analysed using a generalised linear mixed model (with log link and quasi-Poisson distribution) adjusting for time to account for secular trends as well as important contextual factors such as number of providers and readiness for change. We will inspect missing data, and if more than 10% of the sample has missing values, we will use multiple imputation techniques. Otherwise, the maximum-likelihood method of estimation is considered adequate to address missing data in such regression models [117, 118]. Differences between the control and intervention periods and time trends will be estimated using odds ratios and their 95% confidence intervals. Similar regression models will be used (as dictated by the distribution of the data) to assess differences in % of 48-h open slots, walk-in usage, relational continuity and multidisciplinary involvement. Patient experience: A comprehensive description of patients’ experiences will be generated three times over the study. Items that focus on ease of access, perception of interprofessional collaboration, satisfaction with the appointment process and consultations outside the clinic for non-urgent care will be used for longitudinal analysis purposes. Population health: Discontinuity for chronic patients will be analysed using a generalised linear mixed model to assess the impact of the project on the management of chronic patients. Health equity and inclusion: Accessibility and patient experience will be stratified by visible minority status, ethnicity, preferred language, gender and physical or mental ability. If any disparity seems apparent, this issue will be addressed during the improvement efforts. Efficiency: Total costs to the system related to the implementation of the intervention as well as costs per clinic and cohort, accounting for different organisational characteristics, will be calculated. We will analyse the QI coach’s logbook to assign costs to the different tasks performed. Incremental ratios (i.e. change in costs to use the intervention divided by change in the 3rd next available appointment) will also be calculated.

The AA process and outcomes of the intervention (Obj. 4) will be documented 12 months after the end of the intervention to assess the sustainability of its effects over time. Regression models similar to those used in objective 3 will be used to identify the factors that influence sustainability of the intervention effects. Factors such as team context, participation in each intervention activity, support duration (wave) and progress made during the intervention will be included in the model. The association between the sustainability of outcomes and each factor will be estimated using regression estimates and their 95% confidence intervals. We will also evaluate whether the practices put in place (processes) are maintained.

In addition to the analyses described above, one interim analysis will be conducted after 12 months of the intervention. This analysis will focus mainly on the trial’s primary outcome (3rd next available appointment) to identify early evidence of the intervention’s superiority. This study will be monitored by an independent Data Safety and Monitoring Committee (DSMC) formed by the steering committee. The DSMB will consist of an independent healthcare organization expert, a PHC physician and a statistician who are not involved in this study. The interim analysis will be performed by a statistician who is blind to the treatment allocation. Members of the DSMC will also be responsible for developing terms of reference, including stopping rules to be used during interim analysis. The steering committee will be notified by the DSMC only if the latter considers continuance of the study to be futile.

Discussion

The goal of this trial is to improve access to PHC for patients. Thus, this research will have a direct impact on patient experiences of care. Also, this study will develop PHC team capacities through PDSA cycles and large-scale CQI group mentoring. It will be a powerful driver for providers to engage in CQI initiatives with their teams to address timeliness, accessibility, continuity and interprofessional collaboration. We also hope to generate unique opportunities to engage providers in meaningful organisational change based on their local needs and priorities [119] while using readily accessible information from the clinic EMR [34]. Ultimately, the study will also put in place the structure and expertise necessary to allow for the intervention to spread across the province.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first prospective controlled trial that proposes to study an externally facilitated CQI intervention to improve timely access. Our mixed-method approach offers a unique opportunity to contribute to the scientific literature on large-scale CQI cohorts to better understand the processes of a rigorously implemented CQI intervention [120]. This research will contribute to unpacking the process of facilitating change within a PHC clinic, thereby filling the gap on how to generalize CQI interventions [121, 122] and accelerate the spread of effective AA improvement strategies while strengthening local QI culture within clinics [51]. Our study will also provide some insights on the contextual factors and CQI processes that contribute to the sustainability of an intervention aiming to improve access in PHC.

We expect to face two main issues that may limit the impact of the intervention’s effectiveness. First, we cannot overlook resistance to change and clinician commitment to this longitudinal intervention. We believe, however, that the socio-political context in which PHC professionals operate, where access is a growing priority of governing bodies, will help maximize professional engagement and sustain interest. Our bottom-up approach, which is based on CQI techniques rather than performance achievement pursuits and is tailored to each clinic's contextual reality, will also help maintain the professionals’ motivation to change and stay involved in the initiative. Finally, as observed during the pilot project [19], our pragmatic approach, in which data collection to achieve scientific objectives is almost entirely embedded in daily clinical activities (EMR), will ensure that participants quickly see the impact of their involvement in the project without the need for tedious form completion or data extraction processes.

Secondly, the standardization and fidelity of the CQI approach is crucial to enable the production of evidence on the effectiveness of the intervention and allow for its generalization on a larger scale. To do this, we have set up a rigorous journaling process for the four coaches who will be involved in the project for the purposes of monitoring the intervention and quickly bringing modifications if necessary. Team meetings (coaches and the two principal investigators) inspired by medical rounds have also been planned to share the evolution of the change strategies implemented in each clinic and to promote knowledge sharing between the coaches.

Conclusion

This cluster-controlled trial research project based on a mixed-method approach offers a unique opportunity to contribute to the scientific literature on large-scale CQI cohorts to improve AA in primary care teams and to better understand the processes of CQI.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

References

Boivin A, Lehoux P, Lacombe R, Lacasse A, Burgers J, Grol R. Target for improvement: a cluster randomised trial of public involvement in quality-indicator prioritisation (intervention development and study protocol). Implement Sci. 2011;6(1):45.

Canadian Institute for Health Information. How canada compares: results from the commonwealth fund’s 2020 international, health policy survey of the general population in 11 countries. Ottawa, ON: CIHI; 2021.

Gulliford M. Access to primary care and public health. Lancet Public Health. 2017;2(12):e532–3.

Institute of Medicine (US). Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington: National Academies Press; 2003. p. 2003.

Murray M, Berwick DM. Advanced Access: reducing waiting and delays in primary care. JAMA. 2003;289(8):1035.

Breton M, Maillet L, Paré I, Malham SA, Touati N. Perceptions of the first family physicians to adopt advanced access in the province of Quebec, Canada. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2017;32(4):e316–32.

Bundy DG. Open access in primary care: results of a North Carolina pilot project. Pediatrics. 2005;116(1):82–7.

Fournier J, Heale R, Rietze LL. I can’t wait: Advanced Access decreases wait times in primary healthcare. Healthc Q. 2012;15(1):64–8.

Rose K, Ross JS, Horwitz LI. Advanced access scheduling outcomes: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(13):1150–9.

Hudec JC, MacDougall S, Rankin E. Advanced access appointments. Can Fam Physician. 2010;56(10):e361–7.

Rivas J. Advanced access scheduling in primary care: a synthesis of evidence. J Healthc Manag. 2020;65(3):171–84.

Bennett CC. A healthier future for all Australians: an overview of the final report of the National Health and Hospitals Reform Commission. Med J Aust. 2009;191(7):383–7.

Belardi FG, Weir S, Craig FW. A controlled trial of an Advanced Access appointment system in a residency family medicine center. Fam Med. 2004;36(5):341–5.

Ahluwalia S, Offredy M. A qualitative study of the impact of the implementation of advanced access in primary healthcare on the working lives of general practice staff. BMC Fam Pract. 2005;6(1):39.

Breton M, Gaboury I, Beaulieu C, Sasseville M, Hudon C, Malham SA, et al. Revising the advanced access model pillars: a multimethod study. CMAJ Open. 2022;10(3):E799–806.

Breton M, Maillet L, Duhoux A, Abou Malham S, Gaboury I, Manceau LM, et al. Evaluation of the implementation and associated effects of advanced access in university family medicine groups: a study protocol. BMC Fam Pract. 2020;21(1):1–11.

Hudon C, Luc M, Beaulieu M-C, Breton M, Boulianne I, Champagne L, et al. Implementing advanced access to primary care in an academic family medicine network: participatory action research. Can Fam Physician. 2019;65(9):641–7.

Breton M, Gaboury I, Sasseville M, et al. Development of a self-reported reflective tool on advanced access to support primary healthcare providers: study protocol of a mixed-method research design using an e-Delphi survey. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e046411. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046411.

Gaboury I, Breton M, Perreault K, Bordeleau F, Descôteaux S, Maillet L, et al. Interprofessional advanced access – a quality improvement protocol for expanding access to primary care services. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):812.

Langley GJ, Moen RD, Nolan KM, Nolan TW, Norman CL, Provost LP. The improvement guide: a practical approach to enhancing organizational performance. San Francisco: Wiley; 2009.

Batalden PB, Davidoff F. What is “quality improvement” and how can it transform healthcare? Qual Saf Health Care. 2007;16(1):2–3.

Scoville R, Little K. Comparing lean and quality improvement. Cambridge: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2014. p. 2014.

Pannick S, Sevdalis N, Athanasiou T. Beyond clinical engagement: a pragmatic model for quality improvement interventions, aligning clinical and managerial priorities. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(9):716–25.

Backhouse A, Ogunlayi F. Quality improvement into practice. BMJ. 2020;368:m865.

Hill JE, Stephani AM, Sapple P, Clegg AJ. The effectiveness of continuous quality improvement for developing professional practice and improving health care outcomes: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):23.

Goldberg ZE, Chin NP, Alio A, Williams G, Morse DS. A qualitative analysis of family dynamics and motivation in sessions with 15 women in drug treatment court. Substance Abuse. 2019;13:1178221818818846.

Sharkey S, Hudak S, Horn SD, Barrett R, Spector W, Limcangco R. Exploratory study of nursing home factors associated with successful implementation of clinical decision support tools for pressure ulcer prevention. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2013;26(2):83–92.

van Boekholt TA, Duits AJ, Busari JO. Health care transformation in a resource-limited environment: exploring the determinants of a good climate for change. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2019;12:173–82.

Lucas E, Halcomb E, McCarthy S. Connecting care in the community: what works and what doesn’t. Aust J Prim Health. 2016;22(6):539–44.

Shaw EK, Ohman-Strickland PA, Piasecki A, Hudson SV, Ferrante JM, McDaniel RR Jr, et al. Effects of facilitated team meetings and learning collaboratives on colorectal cancer screening rates in primary care practices: a cluster randomized trial. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(3):220.

Bombard Y, Baker, Orlando, Fancott. Engaging patients to improve quality of care: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2018;13:98.

Johnson KE, Mroz TM, Abraham M, Gray MF, Minniti M. Promoting patient and family partnerships in ambulatory care improvement: a narrative review and focus group findings. Adv Ther. 2016;33(8):1417–39.

Armstrong N, Herbert G, Aveling EL, Dixon-Woods M, Martin G. Optimizing patient involvement in quality improvement. Health Expect. 2013;16(3):e36–47.

Zamboni K, Baker U, Tyagi M, Schellenberg J, Hill Z, Hanson C. How and under what circumstances do quality improvement collaboratives lead to better outcomes? A systematic review. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):27.

Baik D, Abu-Rish Blakeney E, Willgerodt M, Woodard N, Vogel M, Zierler B. Examining interprofessional team interventions designed to improve nursing and team outcomes in practice: a descriptive and methodological review. J Interprof Care. 2018;32(6):719–27.

Willgerodt MA, Abu-Rish Blakeney E, Woodard N, Vogel MT, Liner DA, Zierler B. Impact of leadership development workshops in facilitating team-based practice transformation. J Interprof Care. 2020;34(1):76–86.

Alagoz E, Chih M-Y, Hitchcock M, Brown R, Quanbeck A. The use of external change agents to promote quality improvement and organizational change in healthcare organizations: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):42.

Arvidsson E, Dahlin S, Anell A. Conditions and barriers for quality improvement work: a qualitative study of how professionals and health centre managers experience audit and feedback practices in Swedish primary care. BMC Fam Pract. 2021;22(1):113.

Mader EM, Fox CH, Epling JW, Noronha GJ, Swanger CM, Wisniewski AM, et al. A practice facilitation and academic detailing intervention can improve cancer screening rates in primary care safety net clinics. J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29(5):533–42.

Miller R, Weir C, Gulati S. Transforming primary care: scoping review of research and practice. J Integr Care. 2018;26(3):176–88.

Ye J, Zhang R, Bannon JE, Wang AA, Walunas TL, Kho AN, et al. Identifying practice facilitation delays and barriers in primary care quality improvement. J Am Board Fam Med. 2020;33(5):655–64.

Parchman ML, Anderson ML, Coleman K, Michaels LA, Schuttner L, Conway C, et al. Assessing quality improvement capacity in primary care practices. BMC Fam Pract. 2019;20(1):103.

Ritchie MJ. Using implementation facilitation to foster clinical practice quality and adherence to evidence in challenged settings: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:294.

Goldberg DG, Haghighat S, Kavalloor S, Nichols LM. A qualitative analysis of implementing EvidenceNOW to improve cardiovascular care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2019;32(5):705–14.

Yapa HM, De Neve J-W, Chetty T, Herbst C, Post FA, Jiamsakul A, et al. The impact of continuous quality improvement on coverage of antenatal HIV care tests in rural South Africa: results of a stepped-wedge cluster-randomised controlled implementation trial. PLoS Med. 2020;17(10):e1003150.

Cheung YY, Riblet NBV, Osunkoya TO. Use of iterative cycles in quality improvement projects in imaging: a systematic review. J Am Coll Radiol. 2018;15(11):1587–602.

Wells S, Tamir O, Gray J, Naidoo D, Bekhit M, Goldmann D. Are quality improvement collaboratives effective? A systematic review. BMJ Quality Safety London. 2018;27(3):226.

Wagner DJ, Durbin J, Barnsley J, Ivers NM. Measurement without management: qualitative evaluation of a voluntary audit & feedback intervention for primary care teams. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):419.

Johnson MJ, May CR. Promoting professional behaviour change in healthcare: what interventions work, and why? A theory-led overview of systematic reviews. BMJ Open. 2015;5(9):e008592.

Hanson RF, Schoenwald S, Saunders BE, Chapman J, Palinkas LA, Moreland AD, et al. Testing the Community-Based Learning Collaborative (CBLC) implementation model: a study protocol. Int J Ment Heal Syst. 2016;10:52.

Hirschhorn LR, Ramaswamy R, Devnani M, Wandersman A, Simpson LA, Garcia-Elorrio E. Research versus practice in quality improvement ? Understanding how we can bridge the gap. Int J Qual Health Care. 2018;30(suppl 1):24–8.

Nadeem E, Olin SS, Hill LC, Hoagwood KE, Horwitz SM. Understanding the components of quality improvement collaboratives: a systematic literature review. Milbank Q. 2013;91(2):354–94.

Ho K, Marsden J, Jarvis-Selinger S, Novak Lauscher H, Kamal N, Stenstrom R, et al. A collaborative quality improvement model and electronic community of practice to support sepsis management in emergency departments: investigating care harmonization for provincial knowledge translation. JMIR Res Protoc. 2012;1(2):e6.

Lipshutz A, Fee C, Schell H, Campbell L, Taylor J, Sharpe B, et al. Strategies for success: a PDSA analysis of three QI initiatives in critical care. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34(8):435–44.

Braithwaite J, Churruca K, Long JC, Ellis LA, Herkes J. When complexity science meets implementation science: a theoretical and empirical analysis of systems change. BMC Med. 2018;16(1):63.

Knudsen SV, Laursen HVB, Johnsen SP, Bartels PD, Ehlers LH, Mainz J. Can quality improvement improve the quality of care? A systematic review of reported effects and methodological rigor in plan-do-study-act projects. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):683.

Leape LL, Rogers G, Hanna D, Griswold P, Federico F, Fenn CA, et al. Developing and implementing new safe practices: voluntary adoption through statewide collaboratives. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15(4):289–95.

Hughes RG. Tools and Strategies for Quality Improvement and Patient Safety. In: Hughes RG, editor. Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses. 2008. p. 42.

Hale KE. "Evaluating Best Practices in Group Mentoring: A Mixed Methods Study." Dissertation, Georgia State University. 2020. https://doi.org/10.57709/15895104.

Health Quality Ontario. Quality improvement primers: change concepts and ideas. Toronto: HQO; 2013.

Nembhard IM. All teach, all learn, all improve?: The role of interorganizational learning in quality improvement collaboratives. Health Care Manage Rev. 2012;37(2):154–64.

World Health Organization. Practical guidance for scaling up health service innovations. Copenhagen: WHO; 2009. p. 2009.

Hulscher MEJL, Schouten LMT, Grol RPTM, Buchan H. Determinants of success of quality improvement collaboratives: what does the literature show? BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(1):19.

Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q. 2004;82(4):581–629.

Flynn R, Scott SD. Understanding determinants of sustainability through a realist investigation of a large-scale quality improvement initiative (Lean): a refined program theory. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2020;52(1):65–74.

Kringos DS, Sunol R, Wagner C, Mannion R, Michel P, Klazinga NS, et al. The influence of context on the effectiveness of hospital quality improvement strategies: a review of systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):277.

Harris SB, Green ME, Brown JB, Roberts S, Russell G, Fournie M, et al. Impact of a quality improvement program on primary healthcare in Canada: a mixed-method evaluation. Health Policy. 2015;119(4):405–16.

Green ME, Harris SB, Webster-Bogaert S, Han H, Kotecha J, Kopp A, et al. Impact of a provincial quality-improvement program on primary health care in Ontario: a population-based controlled before-and-after study. CMAJ Open. 2017;5(2):E281–9.

Breton M, Maillet L, Duhoux A, Malham SA, Gaboury I, Manceau LM, et al. Evaluation of the implementation and associated effects of advanced access in university family medicine groups: a study protocol. BMC Fam Pract. 2020;21(1):41.

Brennan SE, Bosch M, Buchan H, Green SE. Measuring team factors thought to influence the success of quality improvement in primary care: a systematic review of instruments. Implement Sci. 2013;8:20.

Brennan SE, Bosch M, Buchan H, Green SE. Measuring organizational and individual factors thought to influence the success of quality improvement in primary care: a systematic review of instruments. Implement Sci. 2012;7:121.

Mate KS, Ngidi WH, Reddy J, Mphatswe W, Rollins N, Barker P. A case report of evaluating a large-scale health systems improvement project in an uncontrolled setting: a quality improvement initiative in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(11):891–8.

Sedgwick P. What is a non-randomised controlled trial? BMJ. 2014;348:g4115.

Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux. Cadre de gestion des GMF GMR-R. Québec: MSSS; 2015.

Crabtree BF, Nutting PA, Miller WL, McDaniel RR, Stange KC, Jaen CR, et al. Primary care practice transformation is hard work: insights from a 15-year developmental program of research. Med Care. 2011;49(Suppl):28.

Baskerville NB, Liddy C, Hogg WJTAoFM. Systematic review and meta-analysis of practice facilitation within primary care settings. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(1):63–74.

Silver SA, Harel Z, McQuillan R, Weizman AV, Thomas A, Chertow GM, et al. How to begin a quality improvement project. 2016;11(5):893–900.

Lipmanowicz H, McCandless K. The surprising power of liberating structures: simple rules to unleash a culture of innovation. WA: Liberating Structures Press Seattle; 2013.

Health Quality Ontario. Writing an Aim Statement. Toronto: HQO. http://www.hqontario.ca/Portals/0/documents/qi/rf-writing-an-aim-statement-en.pdf.

Knox L, Branc C. The Practice Facilitation Handbook: training modules for new facilitators and their trainers. Agency for healthcare research and quality ed. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2013.

Lemire N, Litvak E. L’amélioration en santé: diriger, réaliser, diffuser. Longueil: Agence de la santé et des services sociaux de la Montérégie; 2011.

Arora S, Mate KS, Jones JL, Sevin CB, Clewett E, Langley G, et al. Enhancing collaborative learning for quality improvement: evidence from the improving clinical flow project, a breakthrough series collaborative with project ECHO. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2020;46(8):448–56.

Hemming K, Taljaard M. Sample size calculations for stepped wedge and cluster randomised trials: a unified approach. J Clin Epidemil. 2016;69:137–46.

Hemming K, Kasza J, Hooper R, Forbes A, Taljaard M. A tutorial on sample size calculation for multiple-period cluster randomized parallel, cross-over and stepped-wedge trials using the Shiny CRT calculator. Int J Epidemiol. 2020;49(3):979–95.

DeMets D, Lan K. Interim analysis: the alpha spending function approach. Stat Med. 1994;13(13–14):1341–52.

Black WE, Li L. Use of a model maturity matrix to build a quality improvement infrastructure for psychiatric care. Psychiatr Serv. 2020;71(8):839–42.

Kaplan HC, Froehle CM, Cassedy A, Provost LP, Margolis PA. An exploratory analysis of the model for understanding succcess in quality. Health Care Manag Rev. 2013;38(4):325–38.

Anderson NR, West MA. Measuring climate for work group innovation: Development and Validation of the Team Climate Inventory. J Organ Behav. 1998;19:235–58.

Beaulieu MD, Dragieva N, Del Grande C, Dawson J, Haggerty JL, Barnsley J, et al. The team climate inventory as a measure of primary care teams’ processes: validation of the French version. Healthc Policy. 2014;9(3):40–54.

Olson K, Sinsky C, Rinne ST, Long T, Vender R, Mukherjee S, et al. Cross-sectional survey of workplace stressors associated with physician burnout measured by the Mini-Z and the Maslach burnout inventory. Stress Health. 2019;35(2):157–75.

Linzer M, Smith CD, Hingle S, Poplau S, Miranda R, Freese R, et al. Evaluation of work satisfaction, stress, and burnout among US Internal Medicine Physicians and Trainees. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(10):e2018758.

Berthelsen H, Westerlund H, Bergstrom G, Burr H. Validation of the copenhagen psychosocial questionnaire version III and establishment of benchmarks for psychosocial risk management in Sweden. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(9):3179-201.

Adair KC, Quow K, Frankel A, Mosca PJ, Profit J, Hadley A, et al. The improvement readiness scale of the SCORE survey: a metric to assess capacity for quality improvement in healthcare. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):975.

Sexton JB, Frankel A, Leonard M, Adair K. SCORE: assessment of your work setting Safety, Communication, Operational Reliability, and Engagement. Durham: Duke Center for Healthcare Safety and Quality; 2019.

Shortell SM, O’Brien JL, Carman JM, Foster RW, Hughes EF, Boerstler H, et al. Assessing the impact of continuous quality improvement/total quality management: concept versus implementation. Health Serv Res. 1995;30(2):377–401.

Strating MM, Nieboer AP. Explaining variation in perceived team effectiveness: results from eleven quality improvement collaboratives. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22(11–12):1692–706.

Haggerty JL, Roberge D, Freeman GK, Beaulieu C, Breton M. Validation of a generic measure of continuity of care: when patients encounter several clinicians. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(5):443–51.

Haggerty JL, Levesque JF. Validation of a new measure of availability and accommodation of health care that is valid for rural and urban contexts. Health Expect. 2017;20(2):321–34.

Rose KD, Ross JS, Horwitz LI. Advanced access scheduling outcomes: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(13):1150–9.

Henry BW, Rooney DM, Eller S, Vozenilek JA, McCarthy DM. Testing of the Patients’ Insights and Views of Teamwork (PIVOT) Survey: a validity study. Patient Educ Counsseling. 2014;96(3):346–51.

Levine RE, Fowler FJ Jr, Brown JA. Role of cognitive testing in the development of the CAHPS Hospital Survey. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(6 Pt 2):2037–56.

Mack N, Woodsong C, MacQueen KM, Guest G, Namey E. Qualitative research methods: a data collectors field guide. 2005.

Guest G, Namey EE, Mitchell ML. Participant observation. Collecting qualitative data. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage; 2013. p. 75–110.

Phillippi J, Lauderdale J. A guide to filed notes for qualitative research: context and conversation. Qual Health Res. 2018;28(3):381–8.

Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Assessment scale for collaboratives. Available from: http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Tools/AssessmentScaleforCollaboratives.aspx.

Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, Wisdom JP, Duan N, Hoagwood K. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2015;42(5):533–44.

Thorne S, Kirkham SR, MacDonald-Emes J. Interpretive description: a noncategorical qualitative alternative for developing nursing knowledge. Res Nurs Health. 1997;20(2):169–77.

Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage; 1994. p. 338.

Constantinou CS, Georgiou M, Perdikogianni M. A comparative method for themes saturation (CoMeTS) in qualitative interviews. Qual Res. 2017;17(5):571–88.

Stake RE. Multiple Case Study Analysis. New York: The Guilford Press; 2006.

Sandelowski M. “Casing” the research case study. Res Nurs Health. 2011;34(2):153–9.

Miles M, Huberman A, Saldana J. Qualitative data analysis: a methods sourcebook. 3rd ed. New York: Sage; 2014. p. 408.

Lloyd RC. Understanding variation with run charts. Quality health care : a guide to developing and using indicators. 2nd ed. Burlington: Jones and Bartlett Learning; 2019. p. 187–209.

Lloyd RC. Understanding variation with Shewhart charts. Quality health care : a guide to developing and using indicators. 2nd ed. Burlington: Jones and Bartlett Learning; 2019. p. 210–58.

Woodall WH. The use of control charts in health-care and public-health surveillance. J Qual Technol. 2006;38(2):89–104.

Nundy S, Cooper LA, Mate KS. The quintuple aim for health care improvement: a new imperative to advance health equity. JAMA. 2022;327(6):521–2.

Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. 3rd ed. Hoboken: Wiley; 2020.

van Buuren S. Flexible Imputation of Missing Data. London: Chapman & Hall/CRC Press; 2012.

Braithwaite J. Changing how we think about healthcare improvement. BMJ. 2018;361:k2014.

Hirschhorn LR, Ramaswamy R, Devnani M, Wandersman A, Simpson LA, Garcia-Elorrio E. Research versus practice in quality improvement? Understanding how we can bridge the gap. Int J Qual Health Care. 2018;30(suppl_1):24–8.

Dixon-Woods M, Martin GP. Does quality improvement improve quality? Future Hosp J. 2016;3(3):191–4.

Taylor MJ, McNicholas C, Nicolay C, Darzi A, Bell D, Reed JE. Systematic review of the application of the plan–do–study–act method to improve quality in healthcare. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(4):290.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

This study was peer-reviewed by the Strategy for Patient Oriented Research Primary Care Network and funded by Canadian Institutes of Health Research (#477640) and the Ministère de la santé et des services sociaux.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.B., I.G., E.M. and M.G. led the conceptualization and design of the study, but all authors were involved. M.B. and I.G. will lead the coordination of the study. M.B., I.G. and E.M. wrote the first draft, and all authors critically reviewed it and provided comments to revise and improve it. All authors read and approved the final version.

Authors’ information

Not applicable

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study will be performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and have been approved by by the CISSS-Montérégie-Centre ethics committee (#MP-04–2022-696). The informed consent to participate in the study will be obtained from all participant.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Breton, M., Gaboury, I., Martin, E. et al. Impact of externally facilitated continuous quality improvement cohorts on Advanced Access to support primary healthcare teams: protocol for a quasi-randomized cluster trial. BMC Prim. Care 24, 97 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-023-02048-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-023-02048-y