Abstract

Background

Men are usually excluded from surveys on reproductive health as some works have cast doubts on their ability to accurately report information on reproduction. Recent papers challenged this viewpoint, arguing that the quality of men’s reports depends strongly on use of an appropriate study design. We aimed to explore the relevance of evaluating couples’ use of medical care for infertility based on men’s interviews in a population-based survey.

Methods

The study was based on the last French sexual and reproductive health study (Fecond) conducted by phone interviews among a population-based sample of 2863 men and 4629 women aged 20–49 years.

Results

Among respondents who had ever tried to have a child, the use of infertility medical care by couples (i.e. by the respondents and/or their partners) within the previous 15 years was 16% (95%CI 14 to 18%) based on men’s reports and 17% (95%CI 15 to 18%) based on women’s reports (p = 0.43). Men’s and women’s reports were remarkably concordant on most items (infertility duration, treatment). The main discrepancy concerned male medical checkup, which was reported much more often by male respondents than female respondents (86% vs. 57%, p < 0.001 for sperm analysis, 56% vs. 27%, p < 0.001 for male genital examination).

Conclusions

It is time to trust men to report couples’ infertility medical care in reproductive surveys, as they provide information remarkably concordant with that provided by women. Conversely, women may poorly report the infertility checkups of their male partner.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Infertility is still often perceived as “women’s business” [1, 2]. Social representations have constantly designated women as being accountable for childlessness [3, 4]. After 1910, it was medically recognized that sexually potent men can contribute to infertility [5]. Several works have since revealed a marked variability of sperm count that can be affected by several factors [6]. A passionate debate has arisen regarding a severe decrease of sperm count and more generally regarding an impairment of male reproductive health that has been called the “testicular dysgenesis syndrome” [7, 8]. Other works have claimed that the reproductive biological clock affects not only women through the menopause but also men through a phenomenon controversially called the “andropause” [9,10,11]. Meanwhile, medical recognition of the male contribution to couples’ infertility has constantly increased whereas the contribution of unexplained infertility decreased [12]. Male factors are now recognized as contributing to more than half of all cases of infertility [2, 13, 14]. Despite these advances, it is still a common social belief that women are the (only) one to blame when a couple has difficulties in having a child [3, 15, 16]. Much remains to be done to overcome outdated traditional gender stereotypes [1, 4, 12, 17].

Whatever the origin of infertility, it is the woman’s body that is treated through assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs). Even to overcome male infertility, medical help targets the female partner to obtain a pregnancy [12]. The role of the male partner in reproductive care is so limited that he has been described in the literature as an “onlooker”, a “bystander”, the “spare part” or the “second sex in reproduction” [1, 16,17,18,19,20]. In line with this medical logic, most research has considered that infertility medical care is a “woman’s medical story to tell” [1, 12]. Even in psychosocial research on infertility, men are so marginally considered that the question has been raised: “Where are all the men?” [1].

Men are excluded not only from the medical pathway but also from surveys on reproductive health. Firstly, in line with gender stereotypes, researchers often believe that men would be reluctant to participate in such studies [21]. Secondly, some works have cast doubts on the ability of men to accurately report information on reproduction, even for very basic events such as pregnancies, livebirths and their timing [22, 23]. Comparing answers given by each partner, an American study concluded that men cannot be trusted to report reproductive histories [22]. However, recent papers challenged this viewpoint, arguing that the quality of men’s reports depends strongly on use of an appropriate study design [1, 24]. For men to be effectively involved in reproductive surveys, it has been suggested that men only should be recruited, without interviewing their female partners, in order to overcome the traditional secondary role of males [1, 25]. This methodology was successfully implemented in the American National Survey of Family Growth with a participation rate of 75% among men versus 78% among women [26].

We aimed to investigate whether men and women provide concordant information on infertility medical care when interviewed in a large population-based survey recruiting men independently (the male respondents were not the partners of the female respondents).

Methods

The Fecond (Fertility, Contraception and Sexual Dysfunction) study is a population-based survey conducted in France in 2010. It received institutional review board approval from the French Data Protection Authority (authorization CNIL no. 2009–674). The study methodology has been described in detail elsewhere [27]. This study aimed to explore several sexual and reproductive health issues including infertility medical care.

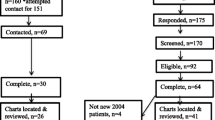

Sampling methodology and selection of the study population

Recruitment in the survey was based on two-stage stratified sampling (Fig. 1). The first sampling stage generated 12,751 representative households by random digit dialing methodology of landline and mobile phone numbers. The second sampling stage selected one person aged 15–49 per household using the Kish method. Considering current doubts as to the feasibility of collecting good-quality data on sexual and reproductive health from men, it was decided to use a higher probability of inclusion for women (60%) than for men (40%) to ensure a larger female sample. To increase participation, a call-back strategy was developed and has been detailed elsewhere [27]. The participation rate was 65% among men and 69% among women. A total of 3373 men and 5272 women participated in the survey by responding to an anonymous telephone interview lasting on average 41 min. To explore use of medical care for infertility, the study population was restricted to 2863 men and 4629 women of reproductive age (20–49 years).

Data collection

The questionnaire collected information on sociodemographic characteristics and on sexual and reproductive health. Detailed information was collected on attempts to have a child (ever if the attempt was successful with the birth of a child or if it was not (yet) successful), on pregnancies (ever planned or unplanned) and their outcomes. Based on this comprehensive information, respondents were classified in two groups: those who had tried at least once in their life to have a child (“ever tried to have a child”) and those who had never tried to have a child. Respondents who had never tried to have a child were not potentially exposed to infertility.

A section of the questionnaire was dedicated to infertility medical care received by the respondents and/or their partners. When the respondents declared that they and/or their partners had had infertility medical care, a detailed questionnaire investigated the couple’s medical pathway more closely. In order to limit memory bias, this detailed questionnaire was only completed when the first consultation for infertility dated from 15 years previously or less.

Identical questions were put to both male and female respondents, the wording being adapted to the respondent’s gender.

Statistical analyses

All analyses were performed using Stata 13.0 software (StataCorp). The concordance between male respondents’ reports and female respondents’ reports was tested. As male and female respondents were independently recruited, men and women were compared using statistical tests for independent observations.

All percentages were weighted to account for the complex sampling design. Firstly, respondents were assigned a sampling weight, inversely proportional to the probability of being selected in the sample. Then, using census data, post-stratification adjustments were applied to reflect the sociodemographic structure of the target population. Finally, the weights were adjusted to the actual sample size. Following guidelines for analysis of complex sample survey design [28, 29], weighted percentages were compared using the χ2 test with the subpopulation option to correctly estimate the standard errors.

Results

Based on male respondents’ reports, in the general population, 11% of couples used infertility medical care versus 16% based on female respondents’ reports (p < 0.001) (Table 1). However, only 53% of male respondents and 66% of female respondents (p < 0.001) had ever tried to have a child, so a large proportion of respondents (47% for men and 34% for women) were in fact outside the scope of infertility. Considering only respondents who ever tried to have a child (Table 2), 16–17% of couples used infertility medical care within the previous 15 years based on male and female reports (p = 0.43).

Among couples who had infertility medical care within the previous 15 years (Table 3), both partners had consulted in about two of three cases, based on male and female reports (70% vs. 63%, p = 0.12). Male and female reports both indicated that medical help was sought at less than 12 months of infertility in about 2 of 5 cases (42% vs. 39%, p = 0.32). Female respondents usually had their first consultation for infertility with a gynecologist (84%). Male respondents also mainly first saw a gynecologist (65%).

Male and female respondents who used infertility medical care agreed that in nearly every case at least one checkup examination was performed (96 vs. 98%, p = 0.18). Male and female reports agreed concerning the frequency of each checkup examination, except for three investigations (men’s genital examination, sperm analysis, hormonal test), more frequently cited by male respondents. The origin of infertility was unspecified for most male and female respondents (61%). Men and women usually found the first doctor “absolutely” supportive (57% vs. 59%, p = 0.83). Moreover, male and female respondents agreed on topics covered during medical care.

Among couples treated for infertility (i.e. the respondents and/or their partners had been treated) within the previous 15 years, male and female respondents agreed on the frequency of use of each specific treatment and on treatment outcome (Table 4). Nearly all couples had ovarian stimulation (84% vs. 87%, p = 0.48). For the majority (70% vs. 73%, p = 0.77), this was the first treatment. In vitro fertilization (IVF) was the second most frequent treatment received by around one-third of the treated population (36% vs. 31%, p = 0.31). Nearly three of five treated couples achieved a birth following treatment (58% vs. 59%, p = 0.75). Fewer men than women declared that treatment was a “very difficult” experience (14% vs. 29%, p = 0.01).

Discussion

In a large representative sample of women and men, we explored use of infertility medical care by couples (the respondents and/or their partners). Based on female respondents, 16% of couples used medical care for infertility in the French population, a frequency consistent with estimations in other developed countries [2, 26, 30]. On the other hand, based on male respondents, only 11% of couples used medical care for infertility, which is about one-third lower than the estimation based on female respondents (16%, p < 0.001). A very similar gender gap was observed in the 2006–2010 National Survey of Family Growth in the USA, with use of infertility services estimated at 17% based on female reports versus 9% based on male reports [26]. When restricting use of medical care for infertility to treatment within the previous 15 years, it remained about one-third lower when declared by men (8%) than when declared by women (11%). There was thus no evidence that the gender gap could be explained by differences in gender-related long-term memory bias. At first sight, the gender discrepancy seemed to be in agreement with results claiming that men cannot be trusted on reproductive topics [22]. However, deeper investigation showed that this apparent discrepancy resulted largely from confusion bias.

Using classic epidemiological methodology [31], the use of infertility medical care was estimated in the exposed population. In this study, to be exposed to infertility, a person must have tried to have a child. Exposure to infertility was thus defined based on the respondent’s fertility intentions and not on his/her reproductive behavior (having unprotected intercourse). An American study demonstrated the gap between the two approaches, as some women had unprotected intercourse but did not try to have a child; they were “okay either way” about getting pregnant and in consequence had a very low level of infertility medical care [32, 33]. When considering respondents having “ever tried to have a child”, male respondents of our French study were much less exposed to the risk of infertility than female respondents (47% vs. 34%, p < 0.001). When considering male and female respondents who had ever tried to have a child (the group exposed to infertility), infertility medical care was much more frequent (21–24%) than in the general population (11–16%). Moreover, male and female reports were quite concordant (21% vs. 24%, p = 0.04). The concordance between male and female reports was even more striking when examining only use of medical care within the previous 15 years (16% vs. 17%, p = 0.43). To conclude, the lower level of infertility care declared by men was primarily mediated by higher male probability of never having been exposed to infertility (never having tried to have a child).

To discuss gender differences in infertility care, we need to understand why fewer men ever tried to have a child. A first explanation could be that men tend to declare less often than women that they tried to have a child, i.e. a larger gap between intentions and behavior among men, possibly because they may more often be “okay either way” about pregnancy. However, the gap was probably largely explained by gender differences in demographic and sociological phenomena. In France, 14% of women, but 21% of men, finally remain childless [34]. Nearly all women and men (95%) would like to become a parent [2, 35], but not everyone has the opportunity to try to have a child. The major barrier to parenthood is to have never lived in a couple relationship, with strong social inequalities in the “game of love” for men [36]. Socially disadvantaged men have difficulties in finding a partner, whereas disadvantaged women do not face such “exclusion from the marriage market” [36, 37]. Conversely, socially advantaged men may have children with different female partners, with a growing tendency to divorce and re-partnership [38]. These gender differences in partnership pathways have a direct impact on the lower proportion of men who have ever tried to have a child and thus have ever been at risk of infertility.

Focusing more specifically on respondents who had used infertility medical care within the previous 15 years, we demonstrated a high level of concordance between male and female respondents. Male respondents declared that the couple’s first consultation for infertility (the first consultation of whoever consulted first, the woman and/or the man) occurred at an early stage (less than 1 year of infertility) in 42% of cases and at a late stage (more than 2 years of infertility) in 10% of cases, which is in line with female respondents’ declarations (39% and 11%, respectively). The high frequency (39–42%) of early use of infertility medical care is in line with the hypothesis that couples have moved from “silence to impatience” on the infertility issue [39]. The “give time to time” approach could be less acceptable for couples in a society where ARTs are increasingly used [40, 41].

Regarding information on who had sought medical help for infertility, male and female reports were not significantly different (p = 0.12), although male respondents tended to declare a higher frequency of male partner medical care. Male and female reports were less concordant on who first sought medical help: male respondents were more likely than female respondents to declare that both partners were present at the first consultation (52% vs. 38%). This probably reflects difficulties in distinguishing between the first consultation for infertility and a routine female gynecological checkup during which the issue of infertility had been discussed. The first doctor consulted by the female respondents was usually a gynecologist (84%). For their first consultation, male respondents also very often consulted a gynecologist (65%). It is likely that this gynecologist was their female partner’s gynecologist and that the female partner was also present at this consultation. Further research would be needed to examine whether a consultation with the female partner’s gynecologist is the most efficient way to include men in infertility care. The need to improve accessibility and medical care for men in sexual and reproductive health services has already been emphasised [42].

With regard to infertility checkup, male and female respondents agreed that at least one investigation had been performed in nearly all couples who sought medical help for infertility (96–98%). Male reports on female partner checkup were remarkably concordant with female reports: 94% (vs. 92%, p = 0.62) reported a gynecologic examination, 66% (vs. 64%, p = 0.65) a temperature curve, 42% (vs. 45%, p = 0.52) an invasive female examination (hysterosalpingogram, hysteroscopy or laparoscopy) and 32% (vs. 34%, p = 0.78) a post-coital test or cervical mucus examination.

With regard to the two investigations specifically concerning the male partner, there was major discrepancy between male and female reports: 86% of male respondents reported sperm analysis versus only 57% of female respondents (p < 0.001) and 56% of male respondents reported male genital examination versus only 27% of female respondents (p < 0.001). Other investigations that could concern both partners also tended to be more frequently cited by male respondents than by female respondents: hormonal checkup (81% vs. 64%, p < 0.001) and sexual transmitted infection testing (61% vs. 52%, p = 0.08). To advance our knowledge, it would have been interesting to cross results on medical checkup with the origin of infertility. Unfortunately, the origin of infertility was very poorly reported by both male and female respondents, as 61% did not declare any specific origin of their infertility. Our results are in line with those of the American National Survey of Family Growth which showed that male partners reported a higher proportion of male examination (82%) than female partners (72%) [43]. This raises the question of whether women can be trusted to declare male infertility examination. The gender gap is so large that we may wonder whether female respondents are not always aware that their male partner has undergone genital examination or sperm analysis. In a Canadian qualitative study, diagnosis of male infertility was often followed by a period of male denial sometimes lasting several years, while the man let his female partner pursue medical testing for female factors of infertility [44]. Denial is probably linked to strong stigmatization of male infertility, often interpreted as proof of male impotence [4, 5, 15, 16, 45]. Because infertile men are ridiculed in society [15, 16, 18], some women prefer to unfairly take the “blame” for the couple’s infertility to protect their male partner from thoughtless or hurtful comments and jokes from family, friends and colleagues [2, 4, 16, 18]. In this context, diagnosis of male infertility can be perceived as threatening the man’s masculinity and infertile men exhibit strong feelings of failure, shame and guilt [16, 18, 46]. Male loss of self-esteem is reflected in the terms used by infertile men to describe themselves, such as “emasculated”, “eunuch”, “loser” or “garbage” [44, 45]. Further research would be needed to confirm the hypothesis that men more reliably report male infertility checkup than their female partner, for example by conducting qualitative studies with semi-directive interviews including both partners of the same couples to explore the interaction and logics of the two partners.

Among couples treated for infertility, male and female reports were remarkably concordant, giving very similar pictures of treatment histories. Ovarian stimulation was the first-line treatment, undergone by 84–87% of couples. IVF had been used by 31–36% and husband artificial insemination by 24–28%. At the survey time, 58–59% of treated couples had succeeded in having a child and 12–14% were still being treated and may have had a child later. Considering only respondents who had undergone IVF (those with the most severe infertility), the long-term success rate was 47–52% (men’s and women’s reports, p = 0.64). This rate is identical to that (48%) observed in another study on long-term outcome of patients treated in eight French IVF centers [47].

In our study, among respondents treated for infertility, 66% of female respondents and 51% of male respondents declared that treatment experiences were (very) difficult (p < 0.01), in line with other research showing greater reported distress in women than men [48,49,50]. The greater distress among women is linked to the fact that they are first in line, as infertility treatments affect the female body. However, this gender difference could also reflect a tendency to comply with traditional gender stereotypes, women being expected to voice their sadness whereas men are supposed to play the “emotional rock”, the “committed and supportive partner” [4, 17, 19, 51, 52].

Conclusions

To conclude, it is time to trust men to report infertility medical care in reproductive surveys. The information they provided is remarkably concordant with that based on women’s reports. Male reports were of high quality even when relating to female partner checkup. Conversely, female respondents may poorly report the infertility checkups of their male partner. Further research is needed on this issue. We demonstrated that gender differences in use of infertility medical care were strongly mediated by differences in opportunities to try to have a child. As men and women have different reproductive pathways, it is important to include men in reproductive health research.

Abbreviations

- ARTs:

-

Assisted Reproductive Technologies

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- CNIL:

-

Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertés (French data protection authority)

- Fecond:

-

Fécondité-Contraception-Dysfonctions sexuelles (French survey. Translation: Fertility-Contraception-Sexual Dysfunction)

- IVF:

-

In Vitro Fertilization

- USA:

-

United States of America

References

Culley L, Hudson N, Lohan M. Where are all the men? The marginalization of men in social scientific research on infertility. Reprod BioMed Online. 2013;27:225–35.

Inhorn MC, Patrizio P. Infertility around the globe: new thinking on gender, reproductive technologies and global movements in the 21st century. Hum Reprod Update. 2015;21:411–26.

Petok WD. Infertility counseling (or the lack thereof) of the forgotten male partner. Fertil Steril. 2015;104:260–6.

Wischmann T, Thorn P. (male) infertility: what does it mean to men? New evidence from quantitative and qualitative studies. Reprod BioMed Online. 2013;27:236–43.

Gannon K, Glover L, Abel P. Masculinity, infertility, stigma and media reports. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59:1169–75.

Handelsman DJ. Myth and methodology in the evaluation of human sperm output. Int J Androl. 2000;23:50–3.

Carlsen E, Giwercman A, Keiding N, Skakkebaek NE. Evidence for decreasing quality of semen during past 50 years. BMJ. 1992;305:609–13.

Skakkebaek NE, Rajpert-De Meyts E, Main KM. Testicular dysgenesis syndrome: an increasingly common developmental disorder with environmental aspects. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:972–8.

Burns-Cox N, Gingell C. The andropause: fact or fiction? Postgrad Med J. 1997;73:553–6.

de La Rochebrochard E, McElreavey K, Thonneau P. Paternal age over 40 years: the ‘amber light’ in the reproductive life of men? J Androl. 2003;24:459–65.

Vermeulen A. Andropause Maturitas. 2000;34:5–15.

Martins MV, Basto-Pereira M, Pedro J, Peterson B, Almeida V, Schmidt L, Costa ME. Male psychological adaptation to unsuccessful medically assisted reproduction treatments: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update. 2016;22:466–78.

Irvine DS. Epidemiology and aetiology of male infertility. Hum Reprod. 1998;13:33–44.

Thonneau P, Marchand S, Tallec A, Ferial ML, Ducot B, Lansac J, Lopes P, Tabaste JM, Spira A. Incidence and main causes of infertility in a resident population (1,850,000) of three French regions (1988-1989). Hum Reprod. 1991;6:811–6.

Miall CE. Community constructs of involuntary childlessness: sympathy, stigma, and social support. Can Rev Sociol Anthropol. 1994;31:392–421.

Throsby K, Gill R. “It’s different for men”: masculinity and IVF. Men Masc. 2004;6:330–48.

Hinton L, Miller T. Mapping men's anticipations and experiences in the reproductive realm: (in)fertility journeys. Reprod BioMed Online. 2013;27:244–52.

Carmeli YS, Birenbaum-Carmeli D. The predicament of masculinity: towards understanding the male's experience of infertility treatments. Sex Roles. 1994;30:663–77.

Hudson N, Culley L. ‘The bloke can be a bit hazy about what’s going on’: men and cross-border reproductive treatment. Reprod BioMed Online. 2013;27:253–60.

Meerabeau L. Husbands’ participation in fertility treatment: they also serve who only stand and wait. Sociol Health Illn. 1991;13:396–410.

Lloyd M. Condemned to be meaningful: non-response in studies of men and infertility. Sociol Health Illn. 1996;18:433–54.

Fikree FF, Gray RH, Shah F. Can men be trusted? A comparison of pregnancy histories reported by husbands and wives. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;138:237–42.

Rendall MS, Clarke L, Peters HE, Ranjit N, Verropoulou G. Incomplete reporting of men's fertility in the United States and Britain. Demography. 1999;36:135–44.

Joyner K, Peters HE, Hynes K, Sikora A, Taber JR, Rendall MS. The quality of male fertility data in major U.S. surveys. Demography. 2012;49:101–24.

Deeney K, Lohan M, Spence D, Parkes J. Experiences of fathering a baby admitted to neonatal intensive care: a critical gender analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75:1106–13.

Chandra A, Copen CE, Stephen EH. Infertility service use in the United States: data from the National Survey of family growth, 1982-2010. Natl Health Stat Report. 2014;73:1–21.

Legleye S, Charrance G, Razafindratsima N, Bohet A, Bajos N, Moreau C. Improving survey participation: cost effectiveness of callbacks to refusals and increased call attempts in a national telephone survey in France. Public Opin Q. 2013;77:666–95.

West BT, Arbor A. A closer examination of subpopulation analysis of complex-sample survey data. Stata J. 2008;8:520–31.

StataCorp. Stata survey data reference manual release 15. College Station: StataCorp LLC; 2017. p. 215.

Schmidt L, Munster K. Infertility, involuntary infecundity, and the seeking of medical advice in industrialized countries 1970-1992: a review of concepts, measurements and results. Hum Reprod. 1995;10:1407–18.

Rothman KJ, Greenland S. Modern epidemiology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013.

Greil AL, McQuillan J, Johnson K, Slauson-Blevins K, Shreffler KM. The hidden infertile: infertile women without pregnancy intent in the United States. Fertil Steril. 2010;93:2080–3.

McQuillan J, Greil AL, Shreffler KM. Pregnancy intentions among women who do not try: focusing on women who are okay either way. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15:178–87.

Mazuy M, Barbieri M, Breton D, d'Albis H. The demographic situation in France: recent developments and trends over the last 70 years. Population. 2015;70:417–36.

Debest C, Mazuy M. Equipe de l'enquête Fecond. Childlessness: a life choice that goest against the norm. Pop Soc. 2014;508:1–4.

Köppen K, Mazuy M, Toulemon L. Childlessness in France. In: Kreyenfeld M, Konietzka D, editors. Childlessness in Europe: contexts, causes, and consequences. Dordrecht: Springer; 2017. p. 77–95.

Toulemon L. Demographic patterns of motherhood and fatherhood in France. In: Bledsoe C, Lerner S, Guyer JI, editors. Fertility and the male life-cycle in the era of fertility decline. New York - Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000. p. 293–330.

Beaujouan E, Solaz A. Racing against the biological clock? Childbearing and sterility among men and women in second unions in France. Eur J Popul. 2013;29:39–67.

Leridon H. Sterility and subfecundity: from silence to impatience? Population. 1992;4:35–54.

Calhaz-Jorge C, de Geyter C, Kupka MS, de Mouzon J, Erb K, Mocanu E, Motrenko T, Scaravelli G, Wyns C, Goossens V. Assisted reproductive technology in Europe, 2012: results generated from European registers by ESHRE. Hum Reprod. 2016;31:1638–52.

de La Rochebrochard E. In vitro fertilization in France: 200,000 “test-tube” babies in the last 30 years. Pop Soc. 2008;451:1–4.

Kalmuss D, Tatum C. Patterns of men's use of sexual and reproductive health services. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2007;39:74–81.

Eisenberg ML, Lathi RB, Baker VL, Westphal LM, Milki AA, Nangia AK. Frequency of the male infertility evaluation: data from the national survey of family growth. J Urol. 2013;189:1030–4.

Webb RE, Daniluk JC. The end of the line: infertile men's experiences of being unable to produce a child. Men Masc. 1999;2:6–25.

Nachtigall RD, Becker G, Wozny M. The effects of gender-specific diagnosis on men's and women's response to infertility. Fertil Steril. 1992;57:113–21.

Beutel M, Kupfer J, Kirchmeyer P, Kehde S, Kohn FM, Schroeder-Printzen I, Gips H, Herrero HJ, Weidner W. Treatment-related stresses and depression in couples undergoing assisted reproductive treatment by IVF or ICSI. Andrologia. 1999;31:27–35.

Troude P, Santin G, Guibert J, Bouyer J, La Rochebrochard (de) E, Daifi group. Seven out of 10 couples treated by IVF achieve parenthood following either treatment, natural conception or adoption. Reprod BioMed Online 2016;33:560–567.

Greil AL, Slauson-Blevins K, McQuillan J. The experience of infertility: a review of recent literature. Sociol Health Illn. 2010;32:140–62.

Wichman CL, Ehlers SL, Wichman SE, Weaver AL, Coddington C. Comparison of multiple psychological distress measures between men and women preparing for in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:717–21.

Wright J, Duchesne C, Sabourin S, Bissonnette F, Benoit J, Girard Y. Psychosocial distress and infertility: men and women respond differently. Fertil Steril. 1991;55:100–8.

Edelmann RJ, Connolly KJ. Gender differences in response to infertility and infertility investigations: real or illusory. Br J Health Psychol. 2000;5:365–75.

Jordan C, Revenson TA. Gender differences in coping with infertility: a meta-analysis. J Behav Med. 1999;22:341–58.

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of the Fecond group for their helpful advice and comments in carrying out this study: Jean Bouyer, Géraldine Charrance, Magali Mazuy, Henri Panjo, Nicolas Razafindratsima, Arnaud Régnier-Loilier, Virginie Rozée, Laurent Toulemon. We also thank Nathalie Le Bouteillec and Pénélope Troude for their comments, and Nathalie Bajos and Caroline Moreau (principal investigators of the Fecond project) and Aline Bohet (supervisor). The Fecond group also includes Armelle Andro, Lucette Aussel, Dina Bedretdinova, Danielle Hassoun, Mireille Le Guen, Stéphane Legleye, Elise Marsicano, Virginie Ringa, Michel Teboul and Cécile Ventola. We thank Arnaud Bringé, head of the statistics department, National Institute for Demographic Research (INED), Paris, for advice and revision of the statistical analyses. We thank Nina Crowte for her assistance in language editing. We thank Professor Arthur L. Greil and Professor M. Eisenberg for their helpful comments in reviewing this manuscript.

Funding

The Fecond project was supported by a grant from the French Ministry of Health, a grant from the French National Agency of Research (#ANR-08-BLAN-0286-01), and funding from the National Institute of Health and Medical Research (INSERM) and the National Institute for Demographic Research (INED).

Availability of data and materials

Fecond data are available in the French Data Archives for Social Sciences (Réseau Quetelet).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SB and ELR conceived the research, performed the statistical analysis and wrote the paper. Both authors approved the final version of the manuscript and are accountable for all aspects included in it.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Fecond survey received institutional review board approval from the French Data Protection Authority (authorization CNIL no. 2009–674). Participants gave verbal consent following the usual French ethical procedure for surveys based on voluntary phone interviews. The French Authority (CNIL) authorized interviews of minor teenagers aged 15–17 on their sexual and reproductive life based on their own verbal consent. The interviews could be carried out without requesting parental consent as the age of sexual consent is 15 years according to French law [French Penal Code, article 227–25 with open access at https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/ and French Constitutional Court’s Decision n°2011–222 QPC – 17 February 2012 with open access at www.conseil-constitutionnel.fr].

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Belgherbi, S., de La Rochebrochard, E. Can men be trusted in population-based surveys to report couples’ medical care for infertility?. BMC Med Res Methodol 18, 111 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0566-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0566-y