Abstract

Background

The survival of children who suffer cardiac arrest is poor. This study aimed to determine the predictors and outcome of cardiac arrest in paediatric patients presenting to an emergency department of a tertiary hospital in Tanzania.

Methodology

This was a prospective cohort study of paediatric patients > 1 month to ≤ 14 years presenting to Emergency Medicine Department of Muhimbili National Hospital (EMD) in Tanzania from September 2019 to January 2020 and triaged as Emergency and Priority. We enrolled consecutive patients during study periods where patients’ demographic and clinical presentation, emergency interventions and outcome were recorded. Logistic regression analysis was performed to identify the predictors of cardiac arrest.

Results

We enrolled 481 patients, 294 (61.1%) were males, and the median age was 2 years [IQR 1–5 years]. Among studied patients, 38 (7.9%) developed cardiac arrest in the EMD, of whom 84.2% were ≤ 5 years. Referred patients were over-represented among those who had an arrest (84.2%). The majority 33 (86.8%) of those who developed cardiac arrest died. Compromised circulation on primary survey (OR 5.9 (95% CI 2.1–16.6)), bradycardia for age on arrival (OR 20.0 (CI 1.6–249.3)), hyperkalemia (OR 8.2 (95% CI 1.4–47.7)), elevated lactate levels > 2 mmol/L (OR 5.2 (95% CI 1.4–19.7)), oxygen therapy requirement (OR 5.9 (95% CI 1.3–26.1)) and intubation within the EMD (OR 4.8 (95% CI 1.3–17.6)) were independent predictors of cardiac arrest.

Conclusion

Thirty-eight children developed cardiac arrest in the EMD, with a very high mortality. Those who arrested were more likely to present with signs of hypoxia, shock and acidosis, which suggest they were at later stage in their illness. Outcomes can be improved by strengthening the pre-referral care and providing timely critical management to prevent cardiac arrest.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Paediatric cardiac arrest has a high mortality rate and of those who survive, outcomes are often poor, with disability and long-term health care dependence [1].

In high-income countries (HICs) such as the United States (US), nearly 6,000 children receive in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) each year (approximately 0.3% of all hospitalized children) and generally have positive outcomes [2, 3]. In contrast, studies in Sub Saharan Africa have shown that paediatric cardiac arrest in the emergency department ranges between 4.1% and 28% [1, 4].

Recognition of early predictors of cardiac arrest can allow emergency physicians to rapidly identify a child who is at risk of developing cardiac arrest and intervene to prevent it. Several studies in high income countries have looked at predictors of arrest [1, 3, 5], but these may not be relevant in Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) where diseases are different, time to care is longer and health care systems and resources are fewer.

Since the incidence of cardiac arrest in LMICs is higher than in other settings, the predictors may be different [1, 6]. Nevertheless, there is scarcity of data on the predictors of paediatric cardiac arrest in our setting. Emergency Medicine is a relatively new field in Sub Saharan Africa and studies on such predictors have not previously been performed.

Therefore, this study aimed to determine the predictors and outcome of cardiac arrest at the Emergency Medicine Department of Muhimbili National Hospital (EMD) in Tanzania.

Methodology

Study design

This was a prospective cohort study of all critical paediatric patients presenting to the EMD from September 2019 to January 2020.

Study setting

This study was conducted at the EMD at Muhimbili National Hospital (MNH) in Dar es salaam, Tanzania. MNH is a public, tertiary level hospital in the country. The hospital has a full capacity EMD that receives referrals from across the country, as well as serving as an immediate tertiary referral facility for Dar es Salaam. The EMD is the only primary training site for Emergency Medicine (EM) residency training in the country. It is staffed with emergency physicians, residents in an emergency medicine program, medical officers and critical care nurses. The EMD provides emergency care and resuscitation, serving an average of 200 patients a day; approximately one quarter of them are children under 18 years who have gone through multiple levels of care before arriving to the EMD.

Study participants

Paediatric patients aged 28 days to 14 years, triaged as emergency and priority category (equivalent to Emergency Severity Index (ESI) levels 1, 2 and 3, respectively) presenting to the EMD were eligible. ESI is a five-level emergency department triage algorithm that categorizes patients by evaluating the acuity of illness and the resources needed to manage the patient. We collected data on alternate days among consecutive paediatric patients attending EMD. The study was approved by Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences (MUHAS) Institutional Review Board and MNH and parents/guardians provided written consent.

Study protocol

We used a standardized structured case report form to document demographic information, clinical presentation, including results of the physician’s primary survey (compromised airway, breathing or circulation) vital signs, investigations and results, provisional diagnoses, EMD interventions and outcome for all eligible patients, using providers’ and nurses’ clinical notes and observing interventions. Paediatric and advanced life support chart parameters were used as a reference for tachypnoea, tachycardia and bradycardia in different age groups. For patients who arrested, we determined duration of CPR, duration to ROSC and 24-h cardiac arrest outcome for those who attained ROSC. All the investigations and treatment given to patients were based on the provider’s decision.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was paediatric cardiac arrest in the EMD. The secondary outcome was the to provide a descriptive analysis of outcome of paediatric cardiac arrest in the EMD. The sample size estimation was based on a pilot study conducted at EMD MNH from 1st January to 31st March 2019 using age as a predictor of cardiac arrest. Sample size was calculated using the proportion of subjects with age group less than 5 years and 5 years and above (0.55 and 0.45 respectively) and the proportion of subjects who develop cardiac arrest with age group less than 5 years and 5 years and above (0.081 and 0.021 respectively). Using an alpha of 0.5 and power of 0.80, the minimum sample size required was 476 patients.

Data analysis

Data from the CRF was entered into REDCap (version 7.2.2, Vanderbilt, Nashville, TN, USA), imported to Microsoft Excel 2016 and transferred into the Statistical Package for Social Science (version 25.0, IBM, LTD, North Carolina, USA) for analysis. Because the goal of the study was to determine the predictors and outcome of cardiac arrest, patients’ characteristics, initial presentations and management given prior to arrest were considered as covariates. Standard descriptive statistics were reported using median and interquartile range for continuous variables and frequency and percentage for categorical variables.

Variables were age, sex, referral status, length of stay at the referring facility, airway abnormality (patients with airway compromise in primary survey), breathing abnormality (head nodding, nasal flaring, lower chest wall indrawing and the use of accessory muscles), circulatory abnormality (patients with cyanosis, delayed capillary refill and cool/cold extremities), tachycardia, bradycardia, tachypnoea, bradypnea, hypoxia, investigations and management given prior to arrest. To determine the association between candidate variables and risk of developing cardiac arrest, a univariate regression analysis was conducted. Variables associated with cardiac arrest with a p value of < 0.2 were then included in multivariate logistic regression. Duration of CPR was reported with median and interquartile ranges.

Results

During the study period, 3616 paediatric patients presented to the EMD and 745 (20.6%) were seen as emergency and priority. 481(64.6%) consented to be enrolled in the study (Fig. 1).

The overall median age was 2 years [IQR of 1–5 years], where by 372 (77.3%) were ≤ 5 years, 109 (22.7%) were > 5 years. 294 (61.1%) were males. The majority of children (69%) were referred from other health facilities with overall median length of stay at referring facility 2 days [IQR 1–3 days]. On the primary survey, 48.9% of patients had abnormal breathing and 27.9% had abnormal circulation. Tachycardia (for age) was the most frequently reported (46.4%) abnormal vital sign (Table 1).

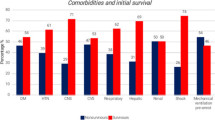

In the entire cohort, sepsis (35.1%) was the most frequently reported provisional EMD diagnosis followed by pneumonia (27.9%) (Fig. 2). Among all children, 65.5% were acidotic, 5.3% had hyperkalemia and 55.7% had elevated lactate levels. More than half of patients received antibiotics and intravenous crystalloid fluids. Over a third of patients required oxygen therapy and less than 10% were intubated. (Table 2)

Overall, 38 (7.9%) patients developed cardiac arrest in the EMD, of whom the majority were ≤ 5 years 32 (84.2%) and referred from other health care facilities 32 (84.2%). Patients who were referred from other health care facilities, patients with compromised airway and breathing who arrived hypoxic and needed oxygen therapy and intubation were significantly more likely to have a cardiac arrest. Moreover, patients with bradycardia on arrival and with compromised circulation in primary survey also predicted cardiac arrest, while patients who received antibiotics were found to have a reduced risk of cardiac arrest in EMD (Table 3).

In multivariate regression only circulation abnormalities on primary survey, bradycardia, hyperkalemia, elevated lactate levels and need for oxygen therapy and intubation were independently associated with cardiac arrest in the EMD, whereas receiving antibiotics was associated with a reduced risk of cardiac arrest in the EMD. (Table 3) Age was not found to be an independent predictor in the multivariate regression.

Outcome of cardiac arrest in paediatric patients who presented to EMD-MNH

Among 38 children who had cardiac arrest, 33 (86.8%) died while in EMD. Only 5 (13.2%) attained ROSC and survived to ICU admission. The median CPR duration was 30 min [IQR 20–38 min] overall, while in those who achieved ROSC, the median duration of CPR was 11 min [IQR 10–13 min]. Most patients who died were ≤ 5yrs (84.2%) or referred from other health care facilities (84.2%). Among those referred, 44.7% spent more than 24 h at the referring facility, 24 h mortality was 35 (92%), with only 3 patients surviving more than 24 h. (Table 4).

Discussion

In this study, we aimed to identify the predictors and outcome of cardiac arrest in paediatric patients presenting to a tertiary emergency medicine department in a LMIC. Patients with compromised circulation, bradycardia as the initial vital sign, hyperkalemia, elevated lactate levels, patients who arrived at a state of requiring oxygen therapy and intubation were the independent predictors of cardiac arrest while in the EMD. The incidence of paediatric cardiac arrest is higher than previously documented in-hospital cardiac arrest in high income countries [7, 8]. Among those who developed cardiac arrest, only 13% survived to ICU admission, which emphasizes the importance of recognizing these predictors before the arrest occurs.

In this study, bradycardia as the initial vital sign was found to be independently associated with cardiac arrest. A multicenter cohort study done in the US also found that paediatric patients with initial bradycardia had a higher likelihood of developing cardiac arrest in the EMD [9]. Bradycardia in children is known to be an ominous sign, usually associated with hypoxia and imminent cardiac arrest. This study confirms the need for early, aggressive resuscitation in children presenting with bradycardia.

In LMIC, most EMD have only a few blood-pressure cuffs for children. BP is rarely measured for young children; therefore, assessment of circulation is mainly done by evaluating the skin and mucous membranes together with the capillary refill time. Using this simple clinical assessment to determine adequacy of circulation during the primary survey, we found compromised circulation was independently associated with cardiac arrest.

Elevated blood lactate levels provide an insight into the presence of impaired tissue perfusion [10]. Lactate has been found to be a useful predictor in identifying critically ill children at high risk of death in the emergency and paediatric intensive care settings but its utility in LMICs EMDs is not as well studied [11]. We found lactate (> 2 mmol/L), done at the point of care, to be an independent predictor of cardiac arrest, suggesting it is a useful addition to physical exam. Moreover, the presence of an elevated lactate in over half of all of our patients suggests that the patients are in very late stages of disease even when they first arrive at our facility. This may be due to delayed care seeking or delays at outside facilities.

Hyperkalemia was also found to be independently associated with cardiac arrest. A previous study also noted that a high potassium level was more likely to be associated with bradycardia, reduced urine output and acidosis [12]. This combination of abnormalities signals not only an increased likelihood of cardiac arrest but also a decreased likelihood of survival [12].

Critically ill children who were hypoxic and arrived at a state of requiring oxygen therapy and intubation were significantly more likely to have a cardiac arrest. Patients who are intubated in the EMD are some of the most critically ill patients and carry a significant risk of deterioration if not intervened early. Due to the lack of sufficient ventilators and ICU beds in our setting, only the sickest children undergo intubation. Therefore, intubation is done at a very late stage in their stay at the EMD and thus carries a high risk of cardiac arrest. Similar to other studies, intubation was found to be independently associated with cardiac arrest [9, 13].

Prior studies in HICs have found that age is an important predictor of paediatric cardiac arrest where by children ≤ 5 years old are more vulnerable [14]. Literature from LMICs also suggests that the highest mortality rate in children who come to the EMD is age ≤ 5 years. In our findings, the majority of paediatric patients who developed cardiac arrest were ≤ 5 years but the difference in age was not significant between the two groups in the regression analysis. One possible explanation for this could be that the presence of other stronger risk factors masked the effect of age as a predictor of arrest.

In our study, over two-thirds of all critically ill patients were referred from other health care facilities. More patients who arrested had been referred and referral was associated with occurrence of cardiac arrest in univariate analysis, but was not an independent predictor in multivariate analysis. We suspect this is due to the fact that referral patients are more likely to critically ill and would arrive with risk factors that were shown to be independent predictors of arrest: circulatory compromise, abnormal vital signs, acidosis and need for intervention. Similar findings were obtained in a retrospective study done in Cincinnati which found that referred patients were significantly more likely to have greater severity of illness [15]. Thus delays caused by hierarchal system of referring patients could also be a contributing factor to a relatively high proportion of arrests in our EMD. Therefore, strengthening of the pre-referral care and early referral of these critically ill patients is important so as to prevent cardiac arrest.

The median duration for CPR in these children was 30 min, but in the small proportion who achieved ROSC, it was 11 min. CPR lasting ≤ 5 min was found to be one of the most important prognostic factors affecting outcome of cardiopulmonary arrest in the EMD [16]. Prolonged resuscitation of more than 15 min was associated with poor outcome during CPR [17]. This suggests that prolonged CPR in the EMD is rarely effective, and duration should be considered in determining when to stop resuscitative efforts.

Limitations

This was a single center study at a tertiary hospital. Patients at our facility may therefore have been sicker and more prone to cardiac arrest; however, it is also possible that some with cardiac arrest never reached our department. However, we see no reason to believe that the risk factors (other than perhaps referral) would be different. Also, patients were enrolled on alternate days so not all arrests were considered. Not all patients had all tests, due to the lack of availability and provider decisions.

Conclusion

In-hospital paediatric cardiac arrest is not infrequent in our setting, and mortality is high after arrest. Immediate recognition of compromised circulation, bradycardia, hyperkalemia, elevated lactate levels, as well as the need for oxygen therapy and intubation in children signify high risk for cardiac arrest with a need for time critical management to prevent arrest and death. This study suggests the need for the use of a warning system and clinical protocols in the EMD, and strengthening pre-referral treatment so as to provide better and more timely care of critically ill children. Research interventions aimed to identify and treat children at risk of cardiac arrest within the resource constraints of this setting are also needed.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusion of this article is available from the authors on request.

References

Olotu A, Ndiritu M, Ismael M, Mohammed S, Mithwani S, Maitland K, et al. Characteristics and outcome of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in hospitalised African children. Resuscitation. 2009;80(1):69–72.

Bhanji F, Topjian AA, Nadkarni VM, Praestgaard AH, Hunt EA, Cheng A, et al. Survival Rates Following Pediatric In-Hospital Cardiac Arrests During Nights and Weekends. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(1):39–45.

Morrison LJ, Neumar RW, Zimmerman JL, Link MS, Newby LK, McMullan PW, et al. Strategies for Improving Survival After In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest in the United States: 2013 Consensus Recommendations: A Consensus Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;127(14):1538–63.

Jofiro G, Jemal K, Beza L, Bacha Heye T. Prevalence and associated factors of pediatric emergency mortality at Tikur Anbessa specialized tertiary hospital: a 5 year retrospective case review study. BMC Pediatrics. 2018;18(1):316. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-018-1287-4 (Cited 20 Jun 2020).

Shimoda-Sakano TM, Schvartsman C, Reis AG. Epidemiology of pediatric cardiopulmonary resuscitation. J de Pediatria. 2020;96(4):409–21.

Edwards-Jackson N, North K, Chiume M, Nakanga W, Schubert C, Hathcock A, et al. Outcomes of in-hospital paediatric cardiac arrest from a tertiary hospital in a low-income African country. Paediatr Int Child Health. 2019;0(0):1–5.

López-Herce J, del Castillo J, Cañadas S, Rodríguez-Núñez A, Carrillo A. In-hospital Pediatric Cardiac Arrest in Spain. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2014;67(3):189–95.

de Mos N, van Litsenburg RRL, McCrindle B, Bohn DJ, Parshuram CS. Pediatric in-intensive-care-unit cardiac arrest: Incidence, survival, and predictive factors. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(4):1209–15.

Meert KL, Donaldson A, Nadkarni V, Tieves KS, Schleien CL, Brilli RJ, et al. Multicenter cohort study of in-hospital pediatric cardiac arrest. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2009;10(5):544–53.

Top APC, Tasker RC, Ince C. The microcirculation of the critically ill pediatric patient. Crit Care. 2011;15(2):213.

Walsh BK, Smallwood CD. Pediatric Oxygen Therapy: A Review and Update. Respir Care. 2017;62(6):645–61.

Lin YR, Syue YJ, Lee TH, Chou CC, Chang CF, Li CJ. Impact of Different Serum Potassium Levels on Postresuscitation Heart Function and Hemodynamics in Patients with Nontraumatic Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. Bioinorg Chem Appl. 2018;5(2018):1–8.

Muhanuzi B, Sawe HR, Kilindimo SS, Mfinanga JA, Weber EJ. Respiratory compromise in children presenting to an urban emergency department of a tertiary hospital in Tanzania: a descriptive cohort study. BMC Emerg Med. 2019;19(1):21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12873-019-0235-4 (Cited 20 Jun 2020).

Meaney PA, Nadkarni VM, Cook EF, Testa M, Helfaer M, Kaye W, et al. Higher survival rates among younger patients after pediatric intensive care unit cardiac arrests. Pediatrics. 2006;118(6):2424–33.

Rinderknecht AS, Ho M, Matykiewicz P, Grupp-Phelan JM. Referral to the Emergency Department by a Primary Care Provider Predicts Severity of Illness. Pediatrics. 2010;126(5):917–24.

Akçay A, Baysal SU, Yavuz T. Factors influencing outcome of inpatient pediatric resuscitation. Turk J Pediatr. 2006;48(4):313–22.

Zaritsky A, Nadkarni V, Hazinski MF, Foltin G, Quan L, Wright J, et al. Recommended Guidelines for Uniform Reporting of Pediatric Advanced Life Support: The Pediatric Utstein Style. Circulation. 1995;92(7):2006–20.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank all the study participants and research assistants for making this project a success.

Funding

This was a non-funded project; the principal investigators used their own funds to support the data collection and logistics.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AOY was involved in the study design conceptualization, data collection, analysis and interpretation, drafted the manuscript, and made all necessary changes to the manuscript. SSK involved in the study design conceptualization, review of the data analysis and interpretation, and critical review of the manuscript. HRS was involved in in the study design, conceptualization, data analysis and interpretation together with critical review of the manuscript. ENP was involved in the study design conceptualization, data analysis and interpretation, and revision of the manuscript. HKM was involved in the revision of the manuscript. ANS was involved in the revision of the manuscript. JAM was involved in the study design conceptualization, data analysis and interpretation, and revision of the manuscript. EJW was involved in the study design conceptualization, data analysis and interpretation together with critical review of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted after obtainin ethical clearence from the MUHAS Institutional Review Board and permision to collect data obtained from MNH administration. Parents/guardians provided written informed consent to participate in the study.

There was no identifiable risk to the participants from the study and patients were not given any experimental medication and no any additional tests were done as part of the research. Therefore, patients received treatment as per standard hospital policies.

I confirm that all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The author declared no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplemental Table 1.

Univariate analysis of predictors of cardiac arrest in paediatric patientstriaged emergency and priority at EMD-MNH.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Yussuf, A.O., Kilindimo, S.S., Sawe, H.R. et al. Predictors and outcome of cardiac arrest in paediatric patients presenting to emergency medicine department of tertiary hospitals in Tanzania. BMC Emerg Med 22, 126 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12873-022-00679-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12873-022-00679-5