Abstract

Background

Lipoprotein (a) [Lp(a)] is an independent risk factor for coronary artery disease (CAD). Recent studies have indicated that statins tend to increase Lp(a) levels by 10–20%. However, the association of statin-mediated increases in Lp(a) levels with CAD has not been determined.

Methods

This study included 488 patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Lp(a) levels were measured at baseline and 1 month after statin therapy. The study endpoints were major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE). Hazard ratios for the MACE were adjusted for potential confounder using Cox regression.

Results

After statin therapy, the mean level of Lp(a) increased by 19.3% from baseline. Lp(a) levels increased in 307 patients (62.9%) with a median elevation of 4.1 mg/dL. Patients with an increase in Lp(a) were at higher risk for MACE than those without an increase in Lp(a) (p = 0.044). Subgroup analyses revealed that a mild-to-moderate increase in Lp(a) was not associated with MACE, whereas there was a strong correlation between the highest quartile increase in Lp(a) (≥ 10.1 mg/dL) and MACE (HR = 2.29, 95%CI = 1.36–3.84, p = 0.002). This correlation was independent of baseline Lp(a) levels but not independent of on-statin Lp(a) levels.

Conclusions

Severe increases in Lp(a) following statin therapy raise the risk of MACE, but a mild-to-moderate increase in Lp(a) may not affect the cardiovascular prognosis of CAD patients. Even if the baseline Lp(a) levels are low, it is necessary to continue testing for Lp(a) concentration at least once after statin.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Statin, an HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor, is overwhelmingly effective in lowering low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels and reducing atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD). It has been recognized as the first-line treatment for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) [1, 2]. An estimated 145.8 million people (2.6%) worldwide are taking statins [3], as for patients with coronary artery disease (CAD), statins are recommended to almost everyone [4]. In spite of this, the fact that statin therapy cannot eliminate residual risks and treat all the lipoproteins that cause atherosclerosis is increasingly accepted [5].

Lipoprotein (a) [Lp(a)] is formed by the covalent binding of apolipoprotein A to a low density lipoprotein (LDL)-like particle [6]. It has the effect of promoting arteriosclerosis, inflammation, calcification, and thrombosis, and is an independent risk factor for ASCVD [7, 8]. Different from other lipid components, the plasma concentration of Lp(a) is mainly regulated by LPA gene which encodes for apolipoprotein(a), and is less affected by external factors [9]. Results on Lp(a) changes after statin therapy are inconsistent. Some studies show a neutral effect [10], while more of them show the effect of increasing Lp(a) [11, 12]. Several large scale meta-analyses summarize the existing research data and indicate that statins increase Lp(a) levels by more than 10% [13, 14]. This has raised concerns as to whether the use of statins increase the cardiovascular risk related to Lp(a). To date, the clinical correlation between statin-mediated increases in Lp(a) levels and CVD has not been demonstrated [15]. The current study was undertaken to investigate the effect of increases in Lp(a) levels following statin therapy on cardiovascular prognosis in a secondary prevention population of CAD.

Patients and methods

Study subjects

This study consecutively enrolled 618 patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with drug-eluting stent implantation in the affiliated Hangzhou First People’s Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine from January 1 to December 31, 2017.

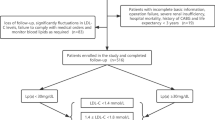

The following subjects were excluded: 1. patients on statin therapy prior to admission (n = 28); 2. patients with PCI unsuccess (n = 3); 3. patients with incomplete basic information or follow-up data (n = 47); 4. patients who discontinued or changed the medication without authorization during the follow-up (n = 39); 5. patients on nicotinic acid or PCSK9 inhibitors (n = 2); 6. patients who lost follow-up (n = 11). As shown in Fig. 1, 488 patients finally fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were classified as the study group. All patients in the study were treated according to the the standard protocols recommended by national guidelines [16, 17].

ACS was defined as acute chest patient occurring with or without persistent ST-segment elevation as well as positive, or negative in case of unstable angina, cardiac enzymes [18]. PCI unsuccess was defined as the residual stenosis diameter of target vessel ≥ 10%, TIMI blood flow less than Grade-III, or associated in-hospital major clinical complications [19].

Data collection

Patient characteristics were obtained from the hospital records. This included information such as age, sex, body mass index, smoking history, family history, comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes mellitus), use of secondary prevention medications (Antiplatelet agents, Lipid-lowering drugs, etc.), laboratory test results [LDL-C, Lp(a), creatinine, etc.] obtained before PCI, records of PCI and the results of blood lipids measurement after 1 month of statin therapy.

Follow-up and study endpoints

All patients received follow-up and repeated measurement of blood lipids at Hangzhou First People’s Hospital in the first month after discharge. The Lp(a) levels were measured by the same assay methodologies. Thereafter, they were followed up at our hospital or in private care clinics every 2–3 months. Endpoint events that occurred within 3 years in patients were collected through outpatient and inpatient records. For patients without an endpoint event record at 36 months after PCI, the occurrence of events was confirmed by telephone contact.

The study endpoints were major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), including cardiovascular death, non-fatal myocardial infarction or ischemic stroke, hospitalization related to unstable angina and unplanned coronary revascularization.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were represented as number (%) and analyzed by chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables that met the normal distribution were represented as mean ± S.D. and analyzed by t-test or variance analysis. Continuous variables without a normal distribution were represented as median (25th percentile,75th percentile) and analyzed by nonparametric test.

Lp(a) was converted into two variables [Lp(a) ≥ 50 mg/dL and log10-transformed Lp(a)]. The hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for MACE were calculated respectively by Cox proportional-hazard regression models, which were used to compare the correlation of pre-and-post statin Lp(a) levels with MACE.

The cumulative MACE—free survival rates between Lp(a) increased ( +) group and Lp(a) increased (-) group were estimated via the Kaplan–Meier method, and the differences were analyzed by the log-rank test. The HR and 95%CI for MACE for each subgroup based on the quartile of the increase in Lp(a) were calculated via Cox proportional hazard models. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 25.0. (Armonk, NY), with a p value of < 0.05 considered significant.

Results

Effect of statins on Lp(a) levels

In this study, 457 (93.65%) patients had a lipid-lowering regimen consisting of statins alone, and 31 (6.35%) received statin plus ezetimibe. As shown in Table 1, the mean level of Lp(a) increased by approximately 19.3% in patients after LLT, a statistically significant difference (p = 0.036). Considering the possible effect of ezetimibe on Lp(a) [20], the changes of Lp(a) levels in patients taking ezetimibe and those not taking ezetimibe were compared. It showed that there was no significant difference between them (19.56% vs 19.30%, p = 0.972), so the influence of ezetimibe was ignored in subsequent steps.

Table S1 describes the detailed use of statins. There was no obvious difference in the type and dose of statins used between the two groups.

Patient characteristics

The average age of patients was 65.9 ± 9.7 years, including 328 males (67.2%). After statin therapy, Lp(a) levels increased in 307 patients (62.9%) with a median elevation of 4.1 mg/dL, and 181 patients (37.1%) had no increase in Lp(a). Characteristics of the population are shown in Table 2. The number of diabetic mellitus patients in Lp(a) increased ( +) group was lower than that in Lp(a) increased (-) group (26.97% vs 38.67%, p = 0.049). The baseline Lp(a) levels were similar between the two groups [14.0 (8.0–29.0) vs 12.0 (7.0–22.0), p = 0.176], but significant differences were observed after statin therapy [20.7 (11.0–40.7) vs 10.0 (6.4–18.2), p < 0.001]. For other clinical features, there was no significant difference between the two groups (p > 0.05).

Association of pre-and-post statin Lp(a) levels with MACE

A total of 105 MACE (detailed in Table S2) were recorded during the 3-year follow-up period (average 31.4months). As shown in Figure 2, the association of pre-and-post statin Lp(a) levels with MACE remained unchanged substantially. Lp(a) levels ≥ 50mg/dL was an independent risk factor for MACE [Baseline: HR = 1.63, 95%CI =1.004-2.64, p = 0.048; On-statin: HR = 1.65, 95%CI =1.03-2.56, p = 0.037]. The log10-transformed Lp(a) was also associated with MACE [Baseline: HR = 1.68, 95%CI =1.03-2.76, p = 0.039; On-statin: HR = 1.79, 95%CI =1.11-2.87, p = 0.016], but the correlation became less significant after multi-factor adjustment [Baseline: HR = 1.34, 95%CI =0.80-2.24, p = 0.263; On-statin: HR = 1.50, 95%CI =0.92-2.45, p = 0.105].

Other risk factors for MACE are listed in Table 3. LDL-C and diabetes mellitus had a strong correlation with MACE, while age and hs-CRP were weak correlation factors for MACE.

In Cox proportional risk model, Lp(a) was converted into continuous variable “Lp(a)1” and categorical variable “Lp(a) levels ≥ 50 mg/dL”. “Lp(a)1” = The log10-transformed Lp(a) level.

“Lp(a) ≥ 50 mg/dL” is generally considered a risk factor for CVD. In this study, 64 patients had baseline Lp(a) ≥ 50 mg/dL and 78 patients had on-statin Lp(a) ≥ 50 mg/dL.

Multivariate adjusted: The variables with p < 0.05 in univariate analysis were adjusted, including age, diabetes, LDL-C and hs-CRP. Univariate analysis is detailed in Table S3.

Effect of statin-mediated increases in Lp(a) levels on cardiovascular prognosis

Of the 105 patients with MACE, 75(24.43%) were in the Lp(a) increased ( +) group and 30 (16.57%) were in the Lp(a) increased (-) group. Patients with an increase in Lp(a) had a higher incidence of MACE ( p = 0.044, Figs. 3).

Then, patients with an increase in Lp(a) were divided into four groups based on the quartile of increases in Lp(a) levels. As shown in Table 4, patients in the highest quartile group had a significantly higher risk of MACE than patients without an increase in Lp(a) (HR = 2.29, 95CI = 1.36–3.84, p = 0.002). And there was no significant difference in MACE risk between other quartile groups and reference patients. (p > 0.05). After adjusting for baseline Lp(a) levels, the correlation did not change notablely. The highest quartile increase in Lp(a) is still closely related to MACE (HR = 2.00, 95CI = 1.18–3.42, p = 0.011). But this correlation disappeared in the model that adjusted for on-statin Lp(a) levels.

Discussion

This study has three major findings: 1) Statin therapy increases Lp(a) levels. The mean level of Lp(a) increased by approximately 19.3% in subjects after statin. 2) Lp(a) levels were associated with MACE, and hazard ratios for Lp(a) levels at both baseline and on-statin were comparable. 3) Patients with a severe increase in Lp(a) after statin therapy have a higher risk of MACE than those without an increase in Lp(a).

Lp(a) is an emerging cardiovascular risk factor. Numerous studies have confirmed its correlation with the onset of coronary heart disease and the recurrence of adverse cardiovascular events. Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration reported that there are continuous, independent, and modest associations of Lp(a) concentration with risk of CAD and stroke. For per 3.5-fold higher than normal Lp(a) concentration, the risk of CAD increased by 13% [21]. Genome-wide association and Mendelian randomized trials showed that the variations at some loci of LPA gene were strongly associated with both an increased level of Lp(a) and an increased risk of CAD, proving the relationship between Lp(a) and CAD at the gene level [22,23,24]. Lp(a) accelerates the progression of low-attenuation coronary plaques (necrotic cores) [25]. As for patients with established cardiovascular disease, especially in young individuals, higher levels of Lp(a) are associated with an increased risk of MACE such as CAD death, myocardial infarction, and urgent revascularization [26,27,28].

Since Lp(a) level is mainly regulated by LPA gene and tends to be constant throughout life, measurement of Lp(a) after statin therapy is rarely performed in clinical practice, leading to a lack of recognition of statin-mediated increases in Lp(a) levels. However, adverse effects of statins on Lp(a) levels have been repeatedly observed in clinical trials. An ILLUMINATE trial showed that Lp(a) levels are positively and dose-dependently correlated with atorvastatin dosage [9]. De Boer et al. reported that statins are associated with approximately 1.1 mg/dL increases in Lp(a) levels compared to placebo, whereas high-intensity statins are associated with 2.6 mg/L increases in Lp(a) levels [29]. Several systematic reviews and meta-analyses most recently indicated that statins increase Lp(a) levels by 10–20% [13, 14]. In this study, statins increased the mean Lp(a) level by 19.6%, similar in extent to the current findings. The underlying mechanisms of statin-mediated increase in Lp(a) levels are not fully defined. It may be due to statin enhence LPA mRNA and apolipoprotein (a) synthesis and secretion. In addition, the increase in plasma PCSK9 protein after statin treatment may also be responsible for the increase in Lp(a) [14].

Do statin-mediated increases in Lp(a) levels cause additional cardiovascular risk? In a meta-analysis, baseline and on-statin Lp(a) levels ≥ 50 mg/dL are associated with a 1.35—and 1.42-fold increased risk of CVD, hazard ratios for high Lp(a) levels at both baseline and on statin are comparable [30]. The JUPITER trial aslo indicated that statin therapy does not significantly increase Lp(a)-associated CVD risk (HR: baseline vs On-statin = 1.18 vs. 1.27) [11]. And we come to the same result (shown in Fig. 2). However, previous studies only compared the overall association of pre-and-post statin Lp(a) levels with CVD/MACE in groups. This research is the first to explore the correlation between the increase of individual Lp(a) level and CVD/MACE after statin therapy, and proves that a significant increase in Lp(a) would raise the risk of MACE. In addition, this correlation is independent of baseline Lp(a), but dependent of on-statin Lp(a), suggesting the importance of repeated measurement of Lp(a) after statin therapy.

Based on the results, we consider it necessary to continue testing for Lp(a) levels at least once after statin therapy, even if the baseline Lp(a) levels are low. For patients with on-statin Lp(a) levels ≥ 50 mg/dL, PCSK9 inhibitors may be used as appropriate to reduce the residual cardiovascular risk [26, 31]. Several Lp(a) targeted therapies have entered into Phase II/III clinical trials and are believed to provide additional benefits to CVD patients in the near future [32,33,34]. However, statin use should not be hindered by fear of an increase in Lp(a). Because most patients have no or mild increase in Lp(a) after statin therapy, which does not increase the risk of cardiovascular events. Moreover, Statins play an irreplaceable role in reducing LDL-C, the chief culprit of atherosclerosis [35, 36]. Reducing LDL-C by 38.67 mg/dL results in cardiovascular benefits comparable to reducing Lp(a) by 67.5 mg/dL [37].

Limitations

First, long-term outpatient follow-up were not all conducted in our hospital, some patients were followed up in private care clinics. We were unable to obtain accurate lipid measurement results and other clinical details for each patient after long-term statin therapy. Therefore, the prognostic implications of subsequent changes in Lp(a) levels cannot be determined. Second, the potential role of ezetimibe in the study is not analyzed. Third, this is a single-center study with a small sample size, and the results are susceptible to incidental factors. We emphasize that these results need to be verified in large-scale clinical studies.

Conclusions

Statins increase Lp(a) levels in some patients with CAD. Severe increases in Lp(a) following statin therapy raise the risk of MACE, whereas a mild-to-moderate increase in Lp(a) may not affect the cardiovascular prognosis of CAD patients. Statin use should not be hindered for fear of an increase in Lp(a), but it is necessary to continue testing for Lp(a) concentration at least once after statin therapy.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

30 December 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-022-03027-4

Abbreviations

- Lp(a):

-

Lipoprotein (a)

- CAD:

-

Coronary artery disease

- ACS:

-

Acute coronary syndrome

- PCI:

-

Percutaneous coronary intervention

- MACE:

-

Major adverse cardiovascular events

- LDL-C:

-

Low density lipoprotein cholesterol

- ASCVD:

-

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- LDL:

-

Low density lipoprotein

- ACS:

-

Acute coronary syndrome

- LLT:

-

Lipid-lowering therapy

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- hs-CRP:

-

High sensitivity C-reactive protein

- TC:

-

Total cholesterol

- HDL-C:

-

High density lipoprotein cholesterol

- TG:

-

Triglycerides

- ACEI:

-

Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor

- ARB:

-

Angiotensin-receptor blocker

- DAPT:

-

Dual antiplatelet therapy

- SAPT:

-

Single antiplatelet therapy

- FUP:

-

Follow up

- CTO:

-

Total coronary occlusion

- UA:

-

Unstable angina

References

Visseren FLJ, Mach F, Smulders YM, Carballo D, Koskinas KC, Bäck M, et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(34):3227–337.

Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, Beam C, Birtcher KK, Blumenthal RS, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;139(25):e1082–143.

Blais JE, Wei Y, Yap KKW, Alwafi H, Ma TT, Brauer R, et al. Trends in lipid-modifying agent use in 83 countries. Atherosclerosis. 2021;328:44–51.

Mach F, Baigent C, Catapano AL, Koskinas KC, Casula M, Badimon L, et al. 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:111–88.

Cho KI, Yu J, Hayashi T, Han SH, Koh KK. Strategies to Overcome Residual Risk During Statins Era. Circ J. 2019;83(10):1973–9.

Kamstrup PR. Lipoprotein(a) and Cardiovascular Disease. Clin Chem. 2021;67(1):154–66.

Duarte Lau F, Giugliano RP. Lipoprotein(a) and its Significance in Cardiovascular Disease: A Review. JAMA Cardiol. 2022;7(7):760–9.

Wilson DP, Jacobson TA, Jones PH, Koschinsky ML, McNeal CJ, Nordestgaard BG, et al. Use of Lipoprotein(a) in clinical practice: A biomarker whose time has come. A scientific statement from the National Lipid Association. J Clin Lipidol. 2019;13(3):374–92.

Hanssen R, Gouni-Berthold I. Lipoprotein(a) Management: Pharmacological and Apheretic Treatment. Curr Med Chem. 2017;24(10):957–68.

Wang X, Li J, Ju J, Fan Y, Xu H. Effect of different types and dosages of statins on plasma lipoprotein(a) levels: A network meta-analysis. Pharmacol Res. 2021;163:105275.

Khera AV, Everett BM, Caulfield MP, Hantash FM, Wohlgemuth J, Ridker PM, et al. Lipoprotein(a) concentrations, rosuvastatin therapy, and residual vascular risk: an analysis from the JUPITER Trial (Justification for the Use of Statins in Prevention: an Intervention Trial Evaluating Rosuvastatin). Circulation. 2014;129(6):635–42.

Arsenault BJ, Petrides F, Tabet F, Bao W, Hovingh GK, Boekholdt SM, et al. Effect of atorvastatin, cholesterol ester transfer protein inhibition, and diabetes mellitus on circulating proprotein subtilisin kexin type 9 and lipoprotein(a) levels in patients at high cardiovascular risk. J Clin Lipidol. 2018;12(1):130–6.

Yeang C, Hung MY, Byun YS, Clopton P, Yang X, Witztum JL, et al. Effect of therapeutic interventions on oxidized phospholipids on apolipoprotein B100 and lipoprotein(a). J Clin Lipidol. 2016;10(3):594–603.

Tsimikas S, Gordts PLSM, Nora C, Yeang C, Witztum JL. Statin therapy increases lipoprotein(a) levels. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(24):2275–84.

Pirillo A, Catapano AL. Statins increase Lp(a) plasma level: is this clinically relevant? Eur Heart J. 2020;41(24):2285–7.

Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Bueno H, ESC Scientific Document Group, et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2018;39(2):119–77.

Collet JP, Thiele H, Barbato E, Barthélémy O, Bauersachs J, Bhatt DL, et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2020;42(14):1289–367 ehaa575.

Zdanyte M, Wrazidlo RW, Kaltenbach S, Groga-Bada P, Gawaz M, Geisler T, et al. Predicting 1-, 3- and 5-year outcomes in patients with coronary artery disease: A comparison of available risk assessment scores. Atherosclerosis. 2021;318:1–7.

Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, Bailey SR, Bittl JA, Cercek B, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. Circulation. 2011;124(23):e574-651.

Awad K, Mikhailidis DP, Katsiki N, Muntner P, Banach M, Lipid and Blood Pressure Meta-Analysis Collaboration (LBPMC) Group. Effect of Ezetimibe Monotherapy on Plasma Lipoprotein(a) Concentrations in Patients with Primary Hypercholesterolemia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Drugs. 2018;78(4):453–62.

Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration, Erqou S, Kaptoge S, Perry PL, Di Angelantonio E, Thompson A, et al. Lipoprotein(a) concentration and the risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and nonvascular mortality. JAMA. 2009;302(4):412–23.

Clarke R, Peden JF, Hopewell JC, Kyriakou T, Goel A, Heath SC, et al. Genetic variants associated with Lp(a) lipoprotein level and coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(26):2518–28.

Guertin J, Kaiser Y, Manikpurage H, Perrot N, Bourgeois R, Couture C, et al. Sex-Specific Associations of Genetically Predicted Circulating Lp(a) (Lipoprotein(a)) and Hepatic LPA Gene Expression Levels With Cardiovascular Outcomes: Mendelian Randomization and Observational Analyses. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2021;14(4):e003271.

Zeng L, Moser S, Mirza-Schreiber N, Lamina C, Coassin S, Nelson CP, et al. Cis-epistasis at the LPA locus and risk of cardiovascular diseases. Cardiovasc Res. 2022;118(4):1088–102.

Kaiser Y, Daghem M, Tzolos E, Meah MN, Doris MK, Moss AJ, et al. Association of Lipoprotein(a) With Atherosclerotic Plaque Progression. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79(3):223–33.

O’Donoghue ML, Fazio S, Giugliano RP, Stroes ESG, Kanevsky E, Gouni-Berthold I, et al. Lipoprotein(a), PCSK9 Inhibition, and Cardiovascular Risk. Circulation. 2019;139(12):1483–92.

Takahashi D, Wada H, Ogita M, Yasuda K, Nishio R, Takeuchi M, et al. Impact of Lipoprotein(a) as a Residual Risk Factor in Long-Term Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients With Acute Coronary Syndrome Treated With Statins. Am J Cardiol. 2022;1(168):11–6.

Gragnano F, Fimiani F, Di Maio M, Cesaro A, Limongelli G, et al. Impact of lipoprotein(a) levels on recurrent cardiovascular events in patients with premature coronary artery disease. Intern Emerg Med. 2019;14(4):621–5.

de Boer LM, Oorthuys AOJ, Wiegman A, Langendam MW, Kroon J, Spijker R, et al. Statin therapy and lipoprotein(a) levels: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2022;29(5):779–92.

Willeit P, Ridker PM, Nestel PJ, Simes J, Tonkin AM, Pedersen TR, et al. Baseline and on-statin treatment lipoprotein(a) levels for prediction of cardiovascular events: individual patient-data meta-analysis of statin outcome trials. Lancet. 2018;392(10155):1311–20.

Bittner VA, Szarek M, Aylward PE, Bhatt DL, Diaz R, Edelberg JM, et al. Effect of Alirocumab on Lipoprotein(a) and Cardiovascular Risk After Acute Coronary Syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(2):133–44.

Tsimikas S, Karwatowska-Prokopczuk E, Gouni-Berthold I, Tardif JC, Baum SJ, Steinhagen-Thiessen E, et al. Lipoprotein(a) Reduction in Persons with Cardiovascular Disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(3):244–55.

Tsimikas S, Moriarty PM, Stroes ES. Emerging RNA Therapeutics to Lower Blood Levels of Lp(a): JACC Focus Seminar 2/4. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77(12):1576–89.

Cesaro A, Schiavo A, Moscarella E, Coletta S, Conte M, et al. Lipoprotein(a): a genetic marker for cardiovascular disease and target for emerging therapies. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown). 2021;22(3):151–61.

Ference BA, Ginsberg HN, Graham I, Ray KK, Packard CJ, Bruckert E, et al. Low-density lipoproteins cause atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. 1. Evidence from genetic, epidemiologic, and clinical studies. A consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(32):2459–72.

Mert GÖ, Başaran Ö, Mert KU, Doğan V, Özlek B, et al. The reasons of poor lipid target attainment for secondary prevention in real life practice: Results from EPHESUS. Int J Clin Pract. 2019;73(9):1–9.

Lamina C, Kronenberg F, Lp(a)-GWAS-Consortium. Estimation of the Required Lipoprotein(a)-Lowering Therapeutic Effect Size for Reduction in Coronary Heart Disease Outcomes: A Mendelian Randomization Analysis. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4(6):575–9.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to cardiac interventional therapy center of the affiliated Hangzhou First People’s Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicinefor their cooperation and assistance.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LJZ contributed to the conception and design of the work. YLF contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the study data. BBG and XBJ contributed to patients follow-up. JMZ and YH contributed to data collection, LJZ drafted the manuscript. JYH critically revised the manuscript. All authors provided final approval and agree to be accountable for all aspects of work, ensuring integrity and accuracy.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The protocol for the study was approved by the ethics committee of the affiliated Hangzhou First People’s Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant at each examination phase.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: figure 3 has been corrected now.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Table S1. Statins used in study subjects. Table S2. Endpoint events for study subjects. Table S3. Univariate COX analysis of risk factors for MACE.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, L., Fang, Y., Gao, B. et al. Effect of an increase in Lp(a) following statin therapy on cardiovascular prognosis in secondary prevention population of coronary artery disease. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 22, 474 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-022-02932-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-022-02932-y