Abstract

Background

Percutaneous left atrial appendage (LAA) closure is an alternative to oral anticoagulation (OAC) for atrial fibrillation (AF) patients with high thromboembolism risk, particularly with contraindications to OAC. The LAA itself could possess proarrhythmogenic properties. As patients undergoing LAA closure could be candidates for cardioversion or ablation, we aimed to evaluate AF disease progression following LAA closure and the outcome of patients undergoing a rhythm control strategy after the procedure.

Methods

The prospective multicenter French Nationwide Observational LAA Closure Registry (FLAAC) comprises 33 French interventional cardiology departments. Patients were included if they fulfilled the following criteria: history of non-valvular AF, successful LAA closure and long-term ECG follow-up.

Results

A total of 331 patients with successful LAA closure were enrolled in the study. Patients mean age was 75.4 ± 0.5 years. The study population was characterized by a high thromboembolic risk (CHA2DS2-VASc score: 4.5 ± 0.1) and frequent comorbidities. The median follow-up was 11.9 months. One hundred and nineteen (36.0%) patients were in sinus rhythm (SR) at baseline. Among SR patients, documented AF was observed in 16 (13.4%) patients whereas 15 (7.1%) patients in AF at baseline restored SR, at the end of follow up. Finally, only 13 patients (4%) underwent procedures to restore SR without complications during the follow-up.

Conclusions

The vast majority of patients undergoing LAA closure have the same AF status at baseline and one year after the index procedure. During the follow-up, a very small proportion (4%) of our population underwent procedures to restore SR without complications whatever the post-procedural antithrombotic strategy was.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common arrhythmia encountered in everyday practice. AF increases the risk of heart failure, stroke and cardiovascular mortality [1,2,3]. The left atrial appendage (LAA) is the main site for AF-related thrombus formation, responsible for stroke [4, 5]. Over the past decade, a new technique has emerged for AF stroke prevention, namely percutaneous LAA closure. This technic has proven to reduce AF-related stroke and is an alternative to oral anticoagulants (OAC) [6,7,8], importantly in patients with definitive OAC contraindications [9].

Concomitantly the LAA structure has been shown to have proarrythmogenic properties and has been implicated in the pathophysiology of persistent AF maintenance [10]. Numerous studies have demonstrated that LAA electrical isolation during persistent AF ablation can improve AF ablation outcomes [11,12,13]. Importantly, the potential effect of LAA closure devices used for LAA closure on cardiac rhythm remains unknown.

Cardioversion and AF catheter ablation are frequently performed to restore and maintain sinus rhythm (SR). These procedures need to be framed by OAC to reduce the risk of stroke [14]. Patients with LAA closure who are contraindicated to OAC could also be candidate for cardioversion and/or catheter ablation. However, there is little known about the long term safety and efficacy within this patient population.

The aim of our study was to evaluate AF burden and AF management including cardioversion and catheter ablation of patients post-LAA closure.

Methods

Design of the study

Patients were enrolled in this prospective, observational, multicenter, cohort from April 2013 to September 2015 in 33 French interventional cardiology departments. Center selection was independent of operator experience to ensure that our patients were representative of daily practice.

The study protocol was approved by a national ethics committee and the study was performed in accordance with the ethical principles stated in the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients gave written inform consent prior to the procedure.

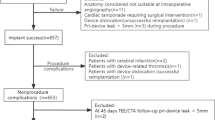

We have previously reported the clinical characteristics and outcome of a cohort of 436 patients included in this registry [15]. Inclusion criteria in the current study were the following: (i) history of non-valvular AF, (ii) successful LAA closure and (iii) long-term ECG follow-up (6 or 12 month visits). Exclusion criteria were (i) age under 18 years old and (ii) subjects unable to sign consent form.

This investigator-initiated study was funded by unrestricted grants from the device manufacturers, who had no role in the study design, data collection and interpretation, or writing of the manuscript.

Left atrial appendage closure and Follow-up

The typical procedure and follow-up were previously described [15]. In summary, a transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) or a cardiac computed tomography angiography (CTA) was performed a few days before LAA closure to assess the size and shape of the LAA and exclude LAA thrombus. The procedure was performed with fluoroscopy and TEE guidance. Both Amplatzer Cardiac Plug™/Amulet™ (Abbott Structural Heart, Plymouth, Minnesota, USA) and Watchman® devices were commercially available in France during the study period. The choice of antithrombotic treatment prescribed at discharge was based on manufacturer recommendations, patient history and non-cardiovascular comorbidities.

The post procedural management of these patients was left at the discretion of their cardiologist. Patients were instructed to contact their referring cardiologist in case of adverse event or hospitalization during the follow-up period. At each visit, clinical symptoms, thromboembolic events, hemorrhagic events, hospitalization, TEE and cardiac CTA-scan results, anti-arrhythmic and antithrombotic treatments were recorded. The cardiac rhythm was assessed during these visits by 12 lead-ECG. Data on interventional procedure (cardioversion, overdrive, catheter ablation) were obtained from patient’s medical records.

Data management

Monitoring

All case report forms were monitored prospectively by an independent research technician. Data were entered in an ACCESS database (Microsoft®, Redmond, Washington, USA) and were subjected to quality control procedures. Missing data and outliers were checked against source documents for completeness and accuracy. All clinical adverse events were adjudicated by an independent committee as (i) related or possibly related to the procedure or (ii) not related to the procedure. All thromboembolic events were classified according to the valve Academic Research Consortium (VARC 2) classification [16]. Thromboembolic and bleeding risk were quantified according to the CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scores, respectively.

Endpoint

The endpoints of this study were: (i) the rate of AF status modification at the end of the follow up period in patients before LAA closure, (ii) the percentage of patients who underwent electrical cardioversion or catheter ablation and their outcomes during the follow up period.

Statistics

Descriptive results are displayed as mean ± SEM or median (interquartile range) for continuous variables, according to the normality of the distributions. Categorical data are described as number (percentage). Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact tests and continuous variables using the Student or Mann–Whitney tests, as appropriate. Two-sided p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Study population

A total of 331 patients with successful LAA closure were enrolled in the study. The main characteristics of the population are presented in Table 1. Patients mean age was 75.4 ± 0.5 years and most of the patients were men (n = 215, 65.0%). The study population was characterized by a high thromboembolic risk (CHA2DS2-VASc score: 4.5 ± 0.1) and frequent comorbidities (Table 1). A history of hemorrhagic event was present in 304 (91.8%) patients (HAS-BLED score: 3.1 ± 0.1). Of note, 100 and 231 patients experienced paroxysmal and persistent/permanent AF, respectively.

The most common indications for LAA closure were: (i) contraindication to anticoagulation in AF patients with a high thromboembolic risk (95.8%) and (ii) history of thromboembolic event despite an adequate anticoagulation (3.6%). A Watchman® device was implanted in 137 (41.4%) patients, an Amplatzer Cardiac Plug™/Amulet™ in 192 (58.0%) patients and another device in 2 patients (0.6%). The device selected after LAA sizing was adequate in most of the patients, and only 1.08 ± 0.02 devices were used per procedure. The median procedural time was 60 [47.5–75] minutes and the mean fluoroscopy time 12 [8.2–18] minutes. Procedure related serious adverse events occurred in 19 patients (5.7%), including 2 device embolizations (0.6%) and 6 pericardial effusions requiring pericardiocentesis (1.8%).

All patients enrolled in this study had a prior history of AF diagnosed on average 3.0 [0.7–6.2] years before LAA closure, and 34 (10.3%) of them have previously undergone an ablation procedure. One hundred and nineteen (36.0%) patients were in SR (SR group) at the baseline visit and 212 (64.0%) in AF (AF group). There was no statistically significant difference in baseline characteristics between both groups (Table 2).

Procedures

Only few patients (13 patients; 4%) included in the FLAAC registry underwent a specific rhythm control intervention during the follow-up period after LAA closure. The clinical characteristics of these patients and the details of these procedures are presented in Table 4.

Four patients with persistent AF or flutter underwent electrical cardioversion or overdrive pacing via an implanted pacemaker (only for atrial flutter). These procedures were performed on average 6.3 ± 1.9 months after LAA closure and restored SR in all of these patients.

Ten procedures of catheter ablation of atrial flutter or fibrillation were performed during the follow-up period, in 9 patients. Six of these procedures were combined with LAA closure (Fig. 1). These interventions were a first ablation procedure in 5 patients and a redo procedure in 4. The procedure was successful in all patients and no major adverse event was observed during the follow-up period.

Only 6 of these 13 patients received anticoagulant agents during the days or weeks before hospitalization for catheter ablation or electrical cardioversion. The baseline antithrombotic treatment of the patients was strengthened after the procedure in 5 of them.

Of note, the population that underwent cardioversion or ablation of an AF during the follow up period was characterized by a lower CHA2DS2-VASc (2.9 ± 0.4 vs. 4.6 ± 0.1, p < 0.001) and HAS-BLED scores (2.3 ± 0.3 vs. 3.2 ± 0.1, p < 0.01) and was younger (70.5 ± 2.3 vs.75.6 ± 0.5, p < 0.05) than the general population included in the registry.

Follow up

Patients were followed up for 11.9 [9.2–13.7] months. Among patients with SR before LAA closure, 103 patients (86.6%) remained in SR at the end of follow up and a documented recurrence of AF was observed in the remaining 16 (13.4%) (Fig. 2). The median time to AF recurrence was 6.1 [1.1–12.4] months after LAA closure.

Similarly, 15 (7.1%) patients with AF at baseline restored SR at the end of the follow up period. Changes in cardiac rhythm after LAA closure are summarized in Fig. 2.

A total of 8 ischemic strokes were recorded during the follow-up period. The stroke rate was not significantly different between patients with SR (3.4%) or AF (1.9%) at baseline (p = 0.46). In addition, a transient ischemic attack occurred in two patients, one in each group. There was no temporal relationship between any thromboembolic event and a documented episode of AF.

Pharmacological antithrombotic treatment

The antithrombotic treatment prescribed after LAA closure varied substantially between patients and is reported in Table 3. At discharge, 93 patients (28.1%) received single antiplatelet therapy, 146 (44.1%) dual-antiplatelet therapy (aspirin and clopidogrel) and 80 (24.2%) short-term anticoagulation (alone or in combination with antiplatelet therapy). Only 12 (3.6%) patients remained without any antithrombotic agent. There was no significant difference in the antithrombotic treatment prescribed at discharge between AF and SR groups.

Antiarrhythmic treatment

Beta blockers were the antiarrhythmic agents the most commonly prescribed in this population (205 patients, 61.9%). Seventy-two (21.8%) and 28 (8.5%) patients received amiodarone or digoxin, respectively. Only 15 (4.5%) and 5 (1.5%) patients received class I or class IV (verapamil, diltiazem) antiarrhythmics. Most of the patients (215 patients, 65.0%) were treated with only one antiarrhythmic agent at discharge and 55 (16.6%) received two antiarrhythmic agents.

Among patients maintaining SR after one year follow-up, 90% were still under antiarrhythmic drugs.

Discussion

Major findings

The main findings of our study are: (1) procedures to restore or maintain SR, including external cardioversion or ablation, in this population, are rarely performed (only 4% of our population), with no major complication observed whatever the periprocedural antithrombotic protocol was. (2) the vast majority of patients undergoing percutaneous LAA closure will have the same AF status before and one year after the index procedure.

AF evolution disease and LAA arrhythmogenicity

AF is commonly attributed to a trigger represented by pulmonary veins (PV) ectopies [17]. This location is particularly implicated in paroxysmal AF pathophysiology. In addition, atrial substrate abnormalities underlie AF maintenance. This substrate is usually located around PVs at the beginning of the disease but over time, the atrial substrate invades the left atrium and to a lesser extent the right atrium. This progression of the disease can be due to AF itself or other cardiac uncontrolled risk factors such as obesity, hypertension or diabetes and lead clinically to persistent or permanent AF. Atrial electrical foci location responsible for AF is a matter of debate as no clear consensus for their detection is available at the moment. LAA, even if rarely associated with AF trigger [18], have been identified in other previous studies, as a potential important origin for AF maintenance during persistent AF. Di Biase et al. [10] first, reported the potential arrythmogenic role of the LAA during AF. In this study, including 987 patients, LAA firing was observed in 27% of patients and was the only source of AF in 8.7% of this population. Other studies have also highlighted the role of LAA in AF maintenance. Notably, Lim et al. [19] demonstrated, using a 252-electrode vest for body surface mapping, that LAA could be a focal driver for persistent AF in 50–55% of cases.

Considering these reports, the LAA has been targeted during AF ablation. Di Biase et al. [20] demonstrated that LAA electrical isolation was associated with better outcomes for patients undergoing persistent AF ablation. Finally, a recent meta-analysis by Friedman et al. confirmed on 7 studies that LAA electrical isolation was associated with lower AF recurrences following AF ablation [21].

More recently, the potential arrhythmogenic effect of LAA closure on AF disease has come into question. Specifically, the LARIAT system, consisting in epicardial snared LAA occlusion (resulting in LAA ischemia) proved to increase significantly freedom from AF off antiarrhythmic drugs at 12 months follow-up (65% vs 39%) [12]. However, the arrhythmic effect of endocardial devices such as the Watchman or ACP/Amulet devices is unclear. Indeed, in contrary to surgical LAA snaring, percutaneous LAA closure could not alter the neuroendocrinal function of LAA. We have shown that, in our cohort of 331 patients undergoing endocardial LAA closure, 87% of those with SR at baseline were in SR at one-year follow-up. In addition, 93% of patients with AF at the time of LAA device implantation were still in AF during long term follow-up.

Numerous studies have evaluated the progression of AF disease over time. It has been conceptually established that AF disease progresses steadily from atrial ectopices to paroxysmal AF, persistent AF and finally permanent AF. The CARAF study evaluated 757 patients with paroxysmal AF and demonstrated that at one year follow-up, 8.6% of patients had developed chronic AF and 24.7% at 5 years. Age, significant aortic stenosis or mitral regurgitation, left atrial enlargement and underlying cardiomyopathy were independently associated with the evolution towards chronic AF [22]. More recently, De Vos et al. studied 1219 patients diagnosed with paroxysmal AF. After one year, 15% of these patients experienced AF disease progression [23].

Our results are consistent with the natural history of AF disease progression and suggest a neutral arrhythmogenic effect of endocardial LAA closure devices.

AF management for patients with LAA occlusion

Sinus rhythm restoration is a cornerstone of AF therapy [14]. This can be achieved either using pharmacological or electrical cardioversion, or performing AF catheter ablation.

In Europe, percutaneous LAA closure is predominantly indicated for patients contraindicated to oral anticoagulation [14]. The FLAAC registry [15] evaluated prospectively the efficacy and safety on French patients undergoing percutaneous LAA closure from 2013 to 2015. Interestingly, the mean age of this population was 75 years and the mean CHA2DS2-VASc score was 4.5 indicating a population with numerous comorbidities. AF rate control strategies are usually preferred in this population rather than rhythm control strategies. This is consistent with the low rate of SR restoration attempts observed in our study (only 4% of the studied population), probably due to the potential complications related to electrophysiogical procedures in this frail population.

LAA closure has been proposed by some authors as a potential alternative to oral anticoagulation in patients without contraindication to OAC. In this specific population, rhythm control achieved with cardioversion or AF ablation is a common management strategy. Of note, patients undergoing rhythm control strategy in our population had a lower CHA2DS2-VASc (2.9 ± 0.4 vs. 4.6 ± 0.1, p < 0.001) and HAS-BLED scores (2.3 ± 0.3 vs. 3.2 ± 0.1, p < 0.01) than the general population included in the registry.

Moreover, as AF ablation requires LA catheterization, it has been proposed in small sample size studies to combine AF ablation and LAA closure [24, 25]. Gadiyaram et al. recently found that the Watchman or Lariat procedure for patients with electrical LAA isolation during AF ablation was safe and oral anticoagulation could be avoided in 98% of this population [26]. Li et al. [27] evaluated 25 patients undergoing combined AF ablation and LAA closure. In 24 patients, oral anticoagulant agents could be stopped at 6 months follow-up. All these studies include small sample sizes and larger series are required to support the efficacy and safety of this combined procedure.

Data evaluating the follow-up of patients with LAA closure undergoing subsequent cardioversion or AF ablation are sparse.

In our population, 7 patients underwent AF ablation. Five of these interventions were combined with LAA closure and two were performed 5 and 7 months after the index procedure, respectively. In addition, as shown in Table 4, one patient had no anticoagulation post-AF ablation without any thromboembolic event after the procedure.

Electrical cardioversion can also be used to restore SR in persistent AF patients. This procedure is systematically followed by a minimum of 1 month of anticoagulation [14] but in some patients experiencing LAA closure, oral anticoagulants are strictly contraindicated and the need for cardioversion can occur in patients with LAA closure without anticoagulation. Electrical cardioversion following LAA closure have been described in some cohorts of patients. However, the anticoagulation protocol following cardioversion was not clearly described. In our prospective cohort, 4 patients experienced electrical cardioversion or overdrive pacing to restore SR. One patient had no anticoagulation before and after atrial arrhythmia reduction and had no thromboembolic event during the follow-up.

Cullen et al. [28] described 93 patients undergoing cardioversion after surgical LAA closure. They found a substantial number of patients (37%) with incomplete LAA closure and LA thrombus (28%) assessed on TEE, highlighting the need to exclude left atrial cavity thrombus before cardioversion in patients with LAA closure.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, we included only patients with successful LAA closure and there was no control group. The AF recurrence rate after LAA closure was therefore compared to data reported in the literature. However, we believe that this indirect comparison provides interesting findings on the effect of LAA closure on cardiac rhythm. Secondly, most of the patients were old with a high rate of comorbidities and were mainly in persistent/permanent AF at baseline explaining that only of few of them underwent procedure to restore SR. Also this strategy could vary, depending on patient characteristics, individual preference or regional practices. Some of these cardioversions or ablation procedures were performed several months after LAA closure and the follow-up reported in this study for these patients was therefore limited. Our results on the safety of these procedures after LAA closure should therefore be taken with caution. Finally, AF status was only assessed according to ECG performed at baseline and at 1 year follow-up. Even if changes in AF burden assessed for instance by 24 h Holter-ECG, may be a more powerful outcome, our population represents a “real world” cohort of patients and we think that ECG modification between baseline and 1 year follow-up still represent an acceptable way to evaluate AF status modification.

Conclusion

In our prospective cohort of 331 patients undergoing percutaneous LAA closure, AF status was not significantly influenced by percutaneous LAA closure after one year follow-up. Thirteen patients (4% of our population) underwent procedure to restore or maintain SR (cardioversion or ablation), some of them without oral anticoagulation. These patients were younger with lower comorbidities and none of them experienced thromboembolic event related to these procedures.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files]. The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AF:

-

Atrial fibrillation

- FLAAC Registry:

-

French LAA Closure Registry

- LAA:

-

Left atrial appendage

- OAC:

-

Oral anticoagulants

- SR:

-

Sinus rhythm

- TEE:

-

Transesophageal echocardiography

References

Andersson T, Magnuson A, Bryngelsson IL, Frobert O, Henriksson KM, Edvardsson N, et al. All-cause mortality in 272,186 patients hospitalized with incident atrial fibrillation 1995–2008: a Swedish nationwide long-term case control study. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:1061–7.

Wolf PA, Abbott RD, Kannel WB. Atrial fibrillation as an independent risk factor for stroke: the Framingham Study. Stroke. 1991;22:983–8.

Stewart S, Hart CL, Hole DJ, McMurray JJ. A population-based study of the longterm risks associated with atrial fibrillation: 20-year follow-up of the Renfrew/Paisley study. Am J Med. 2002;113:359–64.

Madden JL. Resection of the left auricular appendix; a prophylaxis for recurrent arterial emboli. J Am Med Assoc. 1949;140:769–72.

Stoddard MF, Dawkins PR, Prince CR, Ammash NM. Left atrial appendage thrombus is not uncommon in patients with acute atrial fibrillation and a recent embolic event: a transesophageal echocardiographic study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;25:452–9.

Holmes DR, Reddy VY, Turi ZG, Doshi SK, Sievert H, Buchbinder M, PROTECT AF Investigators, et al. Percutaneous closure of the left atrial appendage versus warfarin therapy for prevention of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation: a randomized non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2009;374:534–42.

Reddy VY, Doshi SK, Sievert H, Buchbinder M, Neuzil P, Huber K, PROTECT AF Investigators, et al. Percutaneous left atrial appendage closure for stroke prophylaxis in patients with atrial fibrillation: 2.3-year follow-up of the PROTECT AF (Watchman Left Atrial Appendage System for Embolic Protection in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation) trial. Circulation. 2013;127:720–9.

Reddy VY, Sievert H, Halperin J, Doshi SK, Buchbinder M, Neuzil P, PROTECT AF Steering Committee and Investigators, et al. Percutaneous left atrial appendage closure vs warfarin for atrial fibrillation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312:1988–98.

Reddy VY, Möbius-Winkler S, Miller MA, Neuzil P, Schuler G, Wiebe J, et al. Left atrial appendage closure with the Watchman device in patients with a contraindication for oral anticoagulation: the ASAP study (ASA Plavix Feasibility Study With Watchman Left Atrial Appendage Closure Technology). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:2551–6.

Di Biase L, Burkhardt JD, Mohanty P, Sanchez J, Mohanty S, Horton R, et al. Left atrial appendage: an underrecognized trigger site of atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2010;122:109–18.

Yorgun H, Canpolat U, Kocyigit D, Çöteli C, Evranos B, Aytemir K. Left atrial appendage isolation in addition to pulmonary vein isolation in persistent atrial fibrillation: one-year clinical outcome after cryoballoon-based ablation. Europace. 2017;19:758–68.

Lakkireddy D, Sridhar Mahankali A, Kanmanthareddy A, Lee R, Badhwar N, Bartus K, et al. Left atrial appendage ligation and ablation for persistent atrial fibrillation: the LAALA-AF registry. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2015;1:153–60.

Park HC, Lee D, Shim J, Choi JI, Kim YH. The clinical efficacy of left atrial appendage isolation caused by extensive left atrial anterior wall ablation in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2016;46:287–97.

Kirchhof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D, Ahlsson A, Atar D, Casadei B, ESC Scientific Document Group, et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2893–962.

Teiger E, Thambo JB, Defaye P, Hermida JS, Abbey S, Klug D, French National Left Atrial Appendage Closure Registry (FLAAC) Investigators, et al. Percutaneous left atrial appendage closure is a reasonable option for patients with atrial fibrillation at high risk for cerebrovascular events. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:e005841.

Kappetein AP, Head SJ, Généreux P, Piazza N, van Mieghem NM, Blackstone EH, et al. Updated standardized endpoint definitions for transcatheter aortic valve implantation: the Valve Academic Research Consortium-2 consensus document. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1438–54.

Haissaguerre M, Jais P, Shah DC, Takahashi A, Hocini M, Quiniou G, et al. Spontaneous initiation of atrial fibrillation by ectopic beats originating in the pulmonary veins. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:659–66.

Al Rawahi M, Liang JJ, Kapa S, Lin A, Shirai Y, Kuo L, et al. Incidence of left atrial appendage triggers in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing catheter ablation. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2020;6:21–30.

Lim HS, Hocini M, Dubois R, Denis A, Derval N, Zellerhoff S, et al. Complexity and distribution of drivers in relation to duration of persistent atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:1257–69.

Di Biase L, Burkhardt JD, Mohanty P, Mohanty S, Sanchez JE, Trivedi C, et al. Left atrial appendage isolation in patients with longstanding persistent AF undergoing catheter ablation: BELIEF trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:1929–40.

Friedman DJ, Black-Maier EW, Barnett AS, Pokorney SD, Al-Khatib SM, Jackson KP, et al. Left atrial appendage electrical isolation for treatment of recurrent atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2018;4:112–20.

Kerr CR, Humphries KH, Talajic M, Klein GJ, Connolly SJ, Green M, et al. Progression to chronic atrial fibrillation after the initial diagnosis of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: results from the Canadian Registry of Atrial Fibrillation. Am Heart J. 2005;149:489–96.

de Vos CB, Pisters R, Nieuwlaat R, Prins MH, Tieleman RG, Coelen RJ, et al. Progression from paroxysmal to persistent atrial fibrillation clinical correlates and prognosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:725–31.

Fassini G, Conti S, Moltrasio M, Maltagliati A, Tundo F, Riva S, et al. Concomitant cryoballoon ablation and percutaneous closure of left atrial appendage in patients with atrial fibrillation. Europace. 2016;18:1705–10.

Wintgens L, Romanov A, Phillips K, Ballesteros G, Swaans M, Folkeringa R, et al. Combined atrial fibrillation ablation and left atrial appendage closure: long-term follow-up from a large multicentre registry. Europace. 2018;20:1783–9.

Gadiyaram VK, Mohanty S, Gianni C, Trivedi C, Al-Ahmad A, Burkhardt DJ, et al. Thromboembolic events and need for anticoagulation therapy following left atrial appendage occlusion in patients with electrical isolation of the appendage. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2019;30:511–6.

Li X, Li J, Chu H, Wang L, Shi L, Wang G, et al. Combination of catheter ablation for non-valvular atrial fibrillation and left atrial appendage occlusion in a single procedure. Exp Ther Med. 2018;16:2094–100.

Cullen MW, Stulak JM, Li Z, Powell BD, White RD, Ammash NM, et al. Left atrial appendage patency at cardioversion after surgical left atrial appendage intervention. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;101:675–81.

Acknowledgements

We thank Hamza Bhugaloo for his technical support.

Funding

This study was supported by unrestricted grants from Boston Scientific (26-DRC-2013-08) and St. Jude Medical (26-DRC-2012–25). Boston Scientific and St Jude Medical had no role in the design study, data collection, analysis, interpretation or writing of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NL, ET and PLC contributed to the conception and design of the study. RA, JT, RG, DH and NL were in charge of interpretation of the data and coordination of the study. JSH, JMJ and JLP implanted and included a high number of patients in the study. NL and PLC were in charge of the statistical analysis and interpretation of data. TD made significant corrections in the text of the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol has been approved by an ethics committee (CCTIRS, 24/01/2013, 13.023) and by the French data protection authority (CNIL, 21/03/2013; DR-2013-151). The study was performed in accordance with the ethical principles stated in the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients gave written inform consent prior to the procedure.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Dr Nicolas Lellouche declared to receive consulting fees from Abbott and Boston Scientific. Drs Teiger and Le Corvoisier received significant research grants from Boston Scientific and St. Jude Medical during the conduct of this study. The other authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Lellouche, N., Arrouasse, R., Ternacle, J. et al. Atrial fibrillation evolution and rhythm control strategy following left appendage closure: new insights from the prospective FLAAC registry. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 21, 227 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-021-01994-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-021-01994-8