Abstract

Background

Previous data suggest significant ethnic differences in outcomes following percutaneous coronary revascularization (PCI), though previous studies have focused on subgroups of PCI patients or used administrative data only. We sought to compare outcomes in a population-based cohort of men and women of South Asian (SA), Chinese and “Other” ethnicity.

Methods

Using a population-based registry, we identified 41,792 patients who underwent first revascularization via PCI in British Columbia, Canada, between 2001 and 2010. We defined three ethnic groups (SA, 3904 [9.3%]; Chinese, 1345 [3.2%]; and all “Others” 36,543 [87.4%]). Differences in mortality, repeat revascularization (RRV) and target vessel revascularization (TVR), at 30 days and from 31 days to 2 years were examined.

Results

Adjusted mortality from 31 days to 2 years was lower in Chinese patients than in “Others” (hazard ratio [HR] 0.72; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.53-0.97), but not different between SAs and “Others”. SA patients had higher RRV at 30 days (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 1.30; 95% CI: 1.12-1.51) and from 31 days to 2 years (adjusted hazard ratio [HR] 1.17; 95% CI: 1.06-1.30) compared to “Others”. In contrast, Chinese patients had a lower rate of RRV from 31 days to 2 years (adjusted HR 0.79; 95% CI: 0.64-0.96) versus “Others”. SA patients also had higher rates of TVR at 30 days (adjusted OR 1.35; 95% CI: 1.10-1.66) and from 31 days to 2 years (adjusted HR 1.19; 95% CI: 1.06-1.34) compared to “Others”. Chinese patients had a lower rate of TVR from 31 days to 2 years (adjusted HR 0.76; 95% CI: 0.60-0.96).

Conclusions

SA had higher RRV and TVR rates while Chinese Canadians had lower rates of long-term RRV, compared to those of “Other” ethnicity. Further research to elucidate the reasons for these differences could inform targeted strategies to improve outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In Canada, the largest visible minority is South Asian (25%), followed by Chinese [1]. South Asians (SAs) are younger at presentation, and have higher rates of diffuse coronary artery disease (CAD) compared to non-SAs [2–7]. Differences in outcomes have been noted and may be explained by their higher prevalence of type-2 diabetes and modifiable risk factors such as smoking and obesity, or smaller coronary diameter and novel risk factors for CAD [7–10]. Conversely, Chinese have lower rates of atherosclerosis compared to others [11–13], but the prevalence among Chinese is increasing, attributed to increased dyslipidemia and other environmental influences [14]. A review of over 10 million deaths from the United States found Asian Indian men to have the highest proportional mortality ratio, followed by Asian Indian women and Filipino men, respectively [15]. In Canada, SA patients have paradoxically lower mortality rates following myocardial infarction (MI), despite a higher overall disease burden [16], whereas Chinese had higher short-term mortality following MI in one large cohort study [17].

Revascularization (coronary artery bypass grafting [CABG] or PCI) remains the mainstay of treatment for most patients with symptomatic CAD. Studies have shown that Canadian, British and Indian SAs experience poorer outcomes than non-SAs following CABG [18–22], especially those with diabetes [20]. British researchers have shown higher rates of re-stenosis, target lesion revascularization and CABG post-PCI among SAs versus non-SAs, but no differences in mortality [23, 24]. Canadian studies examining outcomes following acute MI among SA, Chinese and Caucasian patients have had conflicting findings regarding short-term mortality and recurrent MI [17, 21, 25] although a recent study demonstrated longer survival amongst acute coronary syndrome patients who received revascularization [26]. We aimed to compare the outcomes among men and women of SA, Chinese and “Other” ethnicity, following PCI.

Methods

Study design

This retrospective observational cohort study used prospectively collected data from the Cardiac Services British Columbia (CSBC) Cardiac Registry [27], a database including demographic, clinical and procedural outcome details (excluding mortality) of all patients undergoing cardiac procedures in the Canadian province of British Columbia. This included patients with elective (stable coronary disease), urgent (acute coronary syndrome) and emergent (ST-elevation MI) urgency ratings. Mortality data was obtained from the Vital Statistics Agency of British Columbia [28]. We included all patients over 20 years who had undergone PCI in British Columbia as their first revascularization, from April 1, 2001 to October 31, 2010.

Patients with a prior PCI or CABG were excluded for accurate identification of those who required any repeat revascularization (RRV) or target vessel revascularization (TVR). The study received approval from the institution’s Research Ethics Board.

Measures

Demographic data and procedural details were obtained from the CSBCCR. Ethnicity was assigned by CSBC using the Nam Pechan surname analysis program for SA ethnicity (Bradford Health Authority, Bradford, UK), (86–92% sensitivity; greater than 95% specificity) [29, 30] and Quan’s List for Chinese ethnicity [31] (78% sensitivity; 99.7% specificity; 81% positive predictive value; 99.6% negative predictive value). Patients whose names were not identified as either SA or Chinese were classified as “Other”; Canadian census data indicate that approximately 97% of Canadians who do not report SA or Chinese ethnicity are of European ancestry [1]. After surname analysis, the dataset was stripped of all patient identifiers.

Three endpoints (mortality, RRV and TVR) were determined at two time points (30 days and 31 days to 2 years). If a patient experienced more than one RRV, the first procedure was taken as the event. Staged PCI was not considered a RRV. We defined staged PCI as an elective procedure performed within 60 days after the index PCI on a different vessel than that of the index PCI. Furthermore, TVR was defined as a RRV on the same vessel as the index PCI. Four coronary arteries (left main, left anterior descending, left circumflex and right) were used to define staged PCI and TVR.

Statistics

Group differences were assessed using Chi-squared tests for categorical variables and analysis of variance for continuous variables after log transformation, since neither age nor body mass index (BMI) were normally distributed. For 30-day event rates, proportions were calculated, whereas Kaplan-Meier estimates were used to calculate 31-day to 2-year event rates, due to different lengths of follow-up.

Since the hazard ratios (HR) for ethnicity in the early (first 30-days) compared to the late (31 days to 2 years) differed, two separate analyses were performed to further examine ethnicity-based differences in the primary outcomes: logistic regression analysis (up to 30 days) and Cox proportional hazard models (after 30 days), with “Others” as the reference group. When examining repeat revascularization and TVR, patients were censored at the time of death or at the end of two years, whichever came first.

The following clinical covariates were included in the adjusted models: age, BMI, smoking status (current, former, never), prior infarction, history of hypertension, dyslipidemia, cerebrovascular disease, congestive heart disease, diabetes mellitus, peripheral vascular disease, pulmonary disease, liver/gastrointestinal disease, malignancy, dialysis, left ventricular ejection fraction, use of ASA, ACE inhibitor or statin in 24 h before the procedure, as well as peri-procedural variables, including indication (acute coronary syndrome, stable angina vs. other), procedure urgency (elective vs. non-elective), disease severity (3-vessel or left main vs. rest). Due to high missing rates of stent type and cardiogenic shock, additional analysis was performed, including these variables in the adjusted model. Sex was included in the final model regardless of its significance. When the sex effect was significant, sex by ethnicity interaction was then added to see if the effect of ethnicity on outcomes was modified by sex. When a covariate violated the proportional hazard assumption, it was used as a stratifying variable or an interaction term with a time variable was added. We used SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) for all analyses.

Results

Clinical and demographic characteristics

41,792 patients who underwent PCI as a first revascularization were included, of which 3904 (9.3%) were of SA, 1345 (3.2%) Chinese, and 36,543 (87.4%) “Other” ethnicity. There were many statistically significant differences among the three groups (see Table 1), though not all are clinically significant. In terms of the urgency of the PCI, Chinese patients were most likely to undergo an elective procedure, whereas patients of “Other” ethnicity were least likely.

Mortality

Patients of Chinese ethnicity had higher crude rates of 30-day mortality (n = 48, rate = 3.6%; 95% CI: 2.6-4.6) compared to both the SA group (n = 83, rate = 2.1%; 95% CI: 1.7-2.6) and “Others” (n = 799, 2.2%; 95% CI: 2.0-2.3). There was no difference after adjustment in 30-day mortality between Chinese and “Others” (OR 1.18; 95% CI: 0.84-1.66), or SAs and “Others” (OR 0.88; 95% CI: 0.68-1.13) (see Table 2). There were no sex differences in 30-day mortality (OR 1.02; 95% CI 0.88-1.20). Unadjusted 31-day to 2-year mortality was lower in SA Canadians as compared to Chinese patients or Others; however, in adjusted models there was no statistically significant difference in 31-day to 2-year mortality between SA patients and “Others” (HR 0.96; 95% CI: 0.79-1.16), but Chinese patients had lower mortality compared with “Others” (HR 0.72; 95% CI: 0.53-0.97). There were no significant sex differences found in mortality during this period, after adjustment (HR 1.02; 95% CI: 0.91-1.13).

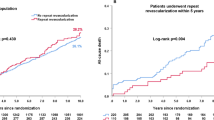

Repeat revascularization

Patients of SA ethnicity had higher crude rates of 30-day repeat revascularization (n = 258, rate = 6.6%; 95% CI: 5.8-7.4) compared to both the Chinese group (n = 58, rate = 4.3%; 95% CI: 3.2-5.4) and “Others” (n = 1698, rate = 4.6%; 95% CI: 4.4-4.9). With adjustment, SA patients rate of RRV remained 30% higher at 30 days (OR 1.30; 95% CI: 1.12-1.51), compared to “Others” (see Table 3). There was no difference in rates of 30-day RRV between Chinese and “Others”.

Although women had lower rates of 30-day RRV compared to men on multivariate analysis (OR 0.85; 95% CI 0.76-0.95), there was no significant sex-by-ethnicity interaction on RRV (p interaction = 0.91).

SA patients also had significantly higher crude rates of RRV from 31 days to 2 years, as compared to “Others” or Chinese patients. On multivariate analysis, SA patients’ RRV remained significantly higher (HR 1.17; 95% CI: 1.06-1.30); in contrast, Chinese patients had a 21% lower adjusted rate of RRV (HR 0.79; 95% CI: 0.64-0.96). There was no sex difference in RRV from 31 days to 2 years post-procedure.

Target vessel revascularization

SA patients (n = 127, rate = 3.3%; 95% CI: 2.8-3.9) had significantly higher rates of TVR at 30 days compared to both the Chinese (n = 27, rate = 2.1%; 95% CI: 1.3-2.8) and Other patients (n = 836, rate = 2.3%; 95% CI: 2.2-2.5). After adjustment, SA patients had a 35% higher rate of 30-day TVR compared to “Others” (OR 1.35; 95% CI: 1.10-1.66), but no difference in 30-day TVR between Chinese patients and “Others” (see Table 4). There was no sex difference in TVR for the first 30 days.

SA patients also had higher crude rates of TVR between 31 days to 2 years than Chinese patients or “Others”. Following adjustment, SA patients also had a significantly higher rate of TVR from 31 days to 2 years (HR 1.19; 95% CI: 1.06-1.34). However, Chinese patients were found to have a lower adjusted rate of TVR, compared to “Others” (HR 0.76; 95% CI: 0.60-0.96). There were no sex differences in TVR between 31 days and 2 years.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the largest Canadian cohort study investigating the association of ethnicity with outcomes of all patients who have undergone PCI (i.e., of elective, urgent and emergent urgency). Due to the large sample size, we found many statistically significant differences in baseline characteristics. Many of these differences were small and their clinical relevance is unclear. The younger age of SAs at presentation for initial PCI and the higher rate of diabetes are consistent with previous reports [11, 14, 16–19, 22–24]. Interestingly, the “Other” ethnicity cohort had the lowest rates of diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidemia, yet had the highest rates of vascular disease. This might be explained by their having the highest rates of current and former smoking.

Finding no sex differences in any of the specified PCI outcomes in our overall sample is consistent with some other researchers’ findings [23, 24, 32]. However, others have shown that, among patients undergoing angiogram for either stable angina or ACS, women have worse outcomes, even after adjusting for revascularization [33, 34]. Identifying other factors (e.g. microvascular dysfunction, diffuse distal disease, higher rate of depression) that might explain these conflicting findings demands further study.

There were higher rates of RRV and TVR between 30 days and 2-years among SA patients, and lower among Chinese. British and other investigators have similarly found significantly higher rates of TVR in SA patients [18–20, 22–24]. Given our adjustment for traditional risk factors and relevant covariates, novel risk factors and smaller coronary diameters may explain these differences [7–10]. However, Anand et al. have shown SA Canadians have higher atherosclerosis and cardiovascular event rates, compared to those of European and Chinese background [14], despite adjusting for traditional risk factors, Framingham risk and novel factors (fibrinogen, plasminogen activator inhibitor- 1, lipoprotein (a), homocysteine). These findings, taken with ours, suggest the possibility of an unknown pathophysiological mechanism of accelerated atherosclerotic disease in patients of SA ethnicity. Our population-based findings indicate no difference in post-PCI mortality among the three groups, which is similar to other reports [32]. We found a non-significant trend toward higher short-term mortality in Chinese patients, which others have found [17, 21]. King et al. reported a tendency among Chinese patients toward atypical symptoms and delayed treatment-seeking for symptoms of ACS, which may explain the trend toward higher short-term mortality [35]. Other explanations may include higher procedural complications or bleeding rates [36]. Chinese patients in our study had significantly lower rates of RRV and TVR from 30 days to 2 years. A prior study examined variations in outcomes among Chinese, Indian Asian and Malay patients following PCI [12] and found Chinese patients had significantly lower rates of MI, RRV and mortality compared to SA patients. Previous Canadian studies have found similarly lower rates of MI and recurrent events among Chinese MI patients, but higher short-term mortality [17, 37]. We were unable to find any literature comparing post-PCI outcomes of Chinese patients to a cohort of patients of European ancestry.

Our study has limitations. Although we used validated surname analysis tools to identify ethnicity [29–31], self-report remains the gold standard [38, 39]. Misclassification of ethnicity could lead to a bias towards the null. Some peri-procedural factors were not available for inclusion in the model including ST-elevation MI as the specific indication for PCI and ejection fraction. We also did not have data on socioeconomic status, or post-PCI medical therapy and risk factor control, any of which might have had an effect on outcomes.

Conclusions

Although mortality rates following PCI are similar among ethnic groups, SAs have higher rates of RRV and TVR as compared to those of “Other” ethnicity. Conversely, Chinese patients had lower rates of RRV and TVR compared to those of “Other” ethnicity. Further investigation of ethnicity-based variability in PCI outcomes is warranted.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- CABG:

-

coronary artery bypass graft

- CAD:

-

coronary artery disease

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- HR:

-

hazard ratio

- MI:

-

myocardial infarction

- OR:

-

odds ratio

- PCI:

-

percutaneous coronary intervention

- RRV:

-

repeat revascularization

- SA:

-

South Asian

- TVR:

-

target vessel revascularization

References

Statistics Canada. National Household Survey Profile, 2011 National Household Survey. Available at: http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/dp-pd/prof/details/page.cfm?Lang=E&Geo1=PR&Code1=01&Data=Count&SearchText=Canada&SearchType=Begins&SearchPR=01&A1=All&B1=All&Custom=&TABID=1.

Gupta M, Doobay AV, Singh N, Anand SS, Raja F, Mawji F, Kho J, Karavetian A, Yi Q, Yusuf S. Risk factors, hospital management and outcomes after acute myocardial infarction in South Asian Canadians and matched control subjects. Can Med Assoc J. 2002;166:717–22.

Zaman MJ, Crook AM, Junghans C, Fitzpatrick NK, Feder G, Timmis AD, Hemingway H. Ethnic differences in long-term improvement of angina following revascularization or medical management: a comparison between South Asians and white Europeans. J Public Health (Oxf). 2009;31:168–74.

Singh N, Gupta M. Clinical characteristics of South Asian patients hospitalized with heart failure. Ethn Dis. 2005;15:615–9.

Dhawan J, Bray CL. Angiographic comparison of coronary artery disease between Asians and Caucasians. Postgrad Med J. 1994;70:625–30.

Gupta M, Singh N, Warsi M, Reiter M, Ali K. Canadian South Asians have more severe angiographic coronary disease than European Canadians despite having fewer risk factors. Can J Cardiol. 2001;17:226C.

Tillin T, Dhutia H, Chambers J, Malik I, Coady E, Mayet J, Wright AR, Kooner J, Shore A, Thom S, Chaturvedi N, Hughes A. South Asian men have different patterns of coronary artery disease when compared with European men. Int J Cardiol. 2008;129:406–13.

Hasan RK, Ginwala NT, Shah RY, Kumbhani DJ, Wilensky RL, Mehta NN. Quantitative angiography in South Asians reveals differences in vessel size and coronary artery disease severity compared to Caucasians. Am J Cardiovasc Dis. 2011;1:31–7.

Tziomalos K, Weerasinghe CN, Mikhailidis DP, Seifalian AM. Vascular risk factors in South Asians. Int J Cardiol. 2008;128:5–16.

Senaratne MP, MacDonald K, De Silva D. Possible ethnic differences in plasma homocysteine levels associated with coronary artery disease between South Asian and East Asian immigrants. Clin Cardiol. 2001;24:730–4.

Meadows TA, Bhatt DL, Cannon CP, Gersh BJ, Rother J, Goto S, Liau CS, Wilson PW, Salette G, Smith SC, Steg PG, REACH Registry Investigators. Ethnic differences in cardiovascular risks and mortality in atherothrombotic disease: insights from the Reduction of Atherothrombosis for Continued Health (REACH) registry. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86:960–7.

Koh AS, Khin LW, Choi LM, Sim LL, Chua TS, Koh TH, Tan JW, Chia S. Percutaneous coronary intervention in Asians--are there differences in clinical outcome? BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2011; doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-11-22.

Critchley J, Liu J, Zhao D, Wei W, Capewell S. Explaining the increase in coronary heart disease mortality in Beijing between 1984 and 1999. Circulation. 2004;110:1236–44.

Anand SS, Yusuf S, Vuksan V, Devanesen S, Teo KK, Montague PA, Kelemen L, Yi C, Lonn E, Gerstein H, Hegele RA, McQueen M. Differences in risk factors, atherosclerosis, and cardiovascular disease between ethnic groups in Canada: the Study of Health Assessment and Risk in Ethnic groups (SHARE). Lancet. 2000;356:279–84.

Jose PO, Frank AT, Kapphahn KI, Goldstein BA, Eggleston K, Hastings KG, Cullen MR, Palaniappan LP. Cardiovascular disease mortality in Asian Americans. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:2486–94.

Quan H, Khan N, Li B, Humphries KH, Faris P, Galbraith PD, Graham M, Knudtson ML, Ghali WA. Invasive cardiac procedure use and mortality among South Asian and Chinese Canadians with coronary artery disease. Can J Cardiol. 2010;26:e236–42.

Khan NA, Grubisic M, Hemmelgarn B, Humphries K, King KM, Quan H. Outcomes after acute myocardial infarction in South Asian, Chinese, and white patients. Circulation. 2010;122:1570–7.

Zindrou D, Bagger JP, Smith P, Taylor KM, Ratnatunga CP. Comparison of operative mortality after coronary artery bypass grafting in Indian subcontinent Asians versus Caucasians. Am J Cardiol. 2001;88:313–6.

Brister SJ, Hamdulay Z, Verma S, Maganti M, Buchanan MR. Ethnic diversity: South Asian ethnicity is associated with increased coronary artery bypass grafting mortality. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;133:150–4.

Hadjinikolaou L, Klimatsidas M, Maria Iacona G, Spyt T, Samani NJ. Short- and medium-term survival following coronary artery bypass surgery in British Indo-Asian and white Caucasian individuals: impact of diabetes mellitus. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2010;10:389–93.

Gasevic D, Khan NA, Qian H, Karim S, Simkus G, Quan H, Mackay MH, O'Neill BJ, Ayyobi AF. Outcomes following percutaneous coronary intervention and coronary artery bypass grafting surgery in Chinese, South Asian and White patients with acute myocardial infarction: administrative data analysis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2013;13:121. doi:10.1186/1471-2261-13-121.

Goldsmith I, Lip GY, Tsang G, Patel RL. Comparison of primary coronary artery bypass surgery in a British Indo-Asian and white Caucasian population. Eur Heart J. 1999;20:1094–100.

Jones DA, Rathod KS, Sekhri N, Junghans C, Gallagher S, Rothman MT, Mohiddin S, Kapur A, Knight C, Archbold A, Jain AK, Mills PG, Uppal R, Mathur A, Timmis AD, Wragg A. Case fatality rates for South Asian and Caucasian patients show no difference 2.5 years after percutaneous coronary intervention. Heart. 2012;98:414–9.

Toor IS, Jaumdally R, Lip GY, Pagano D, Dimitri W, Millane T, Varma C. Differences between South Asians and White Europeans in five year outcome following percutaneous coronary intervention. Int J Clin Pract. 2011;65:1259–66.

Albarak J, Nijjar AP, Aymong E, Wang H, Quan H, Khan NA. Outcomes in young South Asian Canadians after acute myocardial infarction. Can J Cardiol. 2012;28:178–83.

Kaila K, Norris CM, Graham MM, Ali I, Bainey KR. Long-term survival with revascularization in South Asians admitted with an acute coronary syndrome (from the Alberta Provincial Project for Outcomes Assessment in Coronary Heart Disease Registry). Am J Cardiol. 2014;114:395–400.

Cardiac Services BC [creator] (2013): British Columbia Cardiac Registry. Population Data BC [publisher] http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data. BC Ministry of Health (2013) [Approver].

BC Vital Statistics Agency [creator] (2012). Vital Statistics Deaths. Population Data BC [publisher] http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data. BC Vital Statistics Agency (2012) [Approver].

Cummins C, Winter H, Cheng KK, Maric R, Silcocks P, Varghese C. An assessment of the Nam Pehchan computer program for the identification of names of South Asian ethnic origin. J Public Health Med. 1999;21:401–6.

Macfarlane GJ, Lunt M, Palmer B, Afzal C, Silman AJ, Esmail A. Determining aspects of ethnicity amongst persons of South Asian origin: the use of a surname- classification programme (Nam Pehchan). Public Health. 2007;121:231–6.

Quan H, Wang F, Schopflocher D, Norris C, Galbraith PD, Faris P, Graham MM, Knudtson ML, Ghali WA. Development and validation of a surname list to define Chinese ethnicity. Med Care. 2006;44:328–33.

Jones DA, Gallagher S, Rathod KS, Redwood S, de Belder MA, Mathur A, Timmis AD, Ludman PF, Townend JN, Wragg A, NICOR (National Institute for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research). Mortality in South Asians and Caucasians after percutaneous coronary intervention in the United Kingdom: an observational cohort study of 279,256 patients from the BCIS (British Cardiovascular Intervention Society) National Database. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7:362–71.

Izadnegahdar M, Mackay M, Lee MK, Sedlak TL, Gao M, Bairey Merz CN, Humphries KH. Sex and ethnic differences in outcomes of acute coronary syndrome and stable angina patients with obstructive coronary artery disease. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2016;9(2 Suppl 1):S26–35.

King KM, Ghali WA, Faris PD, Curtis MJ, Galbraith PD, Graham MM, Knutson ML. Sex differences in outcomes after cardiac catheterization. Effect modification by treatment strategy and time. JAMA. 2004;291:1220–5.

King KM, Khan NA, Quan H. Ethnic variation in acute myocardial infarction presentation and access to care. Am J Cardiol. 2009;103:1368–73.

Wang TY, Chen AY, Roe MT, Alexander KP, Newby LK, Smith Jr SC, Bangalore S, Gibler WB, Ohman EM, Peterson ED. Comparison of baseline characteristics, treatment patterns, and in-hospital outcomes of Asian versus non-Asian white Americans with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes from the CRUSADE quality improvement initiative. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100:391–6.

Nijjar AP, Wang H, Quan H, Khan NA. Ethnic and sex differences in the incidence of hospitalized acute myocardial infarction: British Columbia, Canada 1995-2002. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2010; doi:10.1186/1471-2261-10-38.

Harding S, Dews H, Simpson SL. The potential to identify South Asians using a computerised algorithm to classify names. Popul Trends. 1999;97:46–9.

Mays VM, Ponce NA, Washington DL, Cochran SD. Classification of race and ethnicity: Implications for public health. Ann Rev Public Health. 2003;24:83–110.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge the statistical support of the BC Centre for Improved Cardiovascular Health (iCVHealth).

Funding

Dr. Mackay was supported by a Cardiac Services of British Columbia Fellowship award and a Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research Scholar Award during this work. Neither of these agencies had any role in the design of the study, analysis and interpretation of data or in writing the manuscript. Cardiac Services BC routinely collects the clinical data related to PCI procedures and provided those data for the necessary linkages to other databases managed by the Ministry of Health, after all necessary approvals were secured.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Cardiac Services BC and BC Vital Statistics Agency (through Population Data BC), but restrictions apply to the availability of these data. The data were used under the Research Agreements for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are, however, available by submitting a data access request to the relevant data stewards.

Disclaimer: All inferences, opinions, and conclusions drawn in this paper are those of the authors, and do not reflect the opinions or policies of the Data Steward(s).

Authors’ contributions

MHM led the research study, including oversight of data analysis and manuscript preparation. RS drafted the manuscript and coordinated several revisions. RHB provided important clinical perspectives on the interpretation of the data and analysis plan, as well as critical review of the manuscript. JEP provided advice about and conducted the statistical analysis, and provided critical review of the statistical aspects of the manuscript. KHH provided pivotal advice about the analysis plan and critical review of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Competing interests

We have no conflicts of interest to disclose. J.E. Park is an employee of the BC Centre for Improved Cardiovascular Health, but since the Centre did not contribute any financial support to this work, there was no conflict of interest.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Providence Health Care/University of British Columbia Research Ethics Board (reference number: H10-03050). As this was a retrospective study and no personal identifiers were ever available to the researchers, the requirement for written consent of participants was waived by the Research Ethics Board.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Mackay, M.H., Singh, R., Boone, R.H. et al. Outcomes following percutaneous coronary revascularization among South Asian and Chinese Canadians. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 17, 101 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-017-0535-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-017-0535-0