Abstract

Background

The association between admission hyperglycemia and adverse outcomes in patients with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) has not been well studied, and the optimal plasma glucose cut-off values for prognosis for NSTEMI patients with and without diabetes have not been determined.

Methods

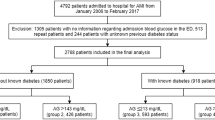

According to glucose level and diabetes status, consecutive NSTEMI patients undergoing PCI (n = 890) were divided into four groups: without diabetes mellitus (DM) and admission plasma glucose (APG) <144 or ≥144 mg/dL; or with DM and APG <180 or ≥180 mg/dL. All patients were followed up at 30 days and 3 years after discharge, and the outcomes were assessed.

Results

Admission hyperglycemia was found in 44 and 28% of the DM and non-DM patients, respectively. Multivariable analyses showed that the APG level was an independent predictor of 30-day and 3-year MACEs. Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis revealed that the appropriate cut-off values were 178 and 145 mg/dL for patients with and without DM, respectively, or 157 mg/dL for all patients.

Conclusions

Admission hyperglycemia may be used to predict 30-day and 3-year MACEs in patients with NSTEMI undergoing PCI, irrespective of diabetes status. However, the optimal admission glucose cut-off values for predicting prognosis differ for patients with or without DM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Stress hyperglycemia in patients admitted with acute myocardial infarction (AMI), with or without diabetes mellitus (DM), has been associated with major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and increased mortality [1–3]. However, most studies have included patients with only ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) [2, 4, 5] or included both STEMI and non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) patients [1, 3, 6–8]. STEMI and NSTEMI are the major types of AMI, and each is associated with different pathophysiological changes, complications, and prognoses [8]. Patients are usually treated with medications [1, 5–7, 9]. Therefore, it is also likely that the cutoff values for blood glucose levels at admission will differ as predictors of prognoses in these two groups.

Currently, the mainstay treatment for AMI is percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). A number of studies have sought to establish the link between blood glucose levels at admission and adverse clinical outcomes and mortality for STEMI patients undergoing PCI. For example, Pres et al. [10] showed that elevated random glucose levels at admission were associated with higher in-hospital and long-term mortality in STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI.

Similar studies performed on NSTEMI patients undergoing primary PCI are limited (although Stefano et al. [11] showed elderly adults with DM and random admission hyperglycemia experienced higher mortality, mostly due to pre-existing cardiovascular and renal damage).

The optimal plasma glucose cut-off value for the prediction of poor outcomes in NSTEMI patients has never been determined. These values probably also differ between AMI patients with or without DM and should be calculated separately. It may be that such a cut-off value is higher in patients with DM, because they have higher average glycemia. Planer et al. [12] reported that the best predictive admission serum glucose cut-off values for 30-day mortality in STEMI patients undergoing PCI with and without DM were 231 and 149, respectively. Timmer et al. [13] determined a cut-off value of 140 mg/dL for non-DM patients with myocardial infarction.

The present study assessed the utility of admission plasma glucose (APG) for predicting MACEs both in the short term (30 days) and long term (3 years) in NSTEMI patients, with and without DM, undergoing PCI. Furthermore, the optimal cut-off APGs for predicting poor outcomes in these patients were determined.

Methods

Study population

The Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University approved this retrospective study, and all participants signed informed consent forms. From January 2009 to October 2012, 890 consecutive NSTEMI patients undergoing PCI in two hospitals in China (First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University and Xi’an Central Hospital) were enrolled in this study. Patients were eligible if they had all three of the following: 1) symptoms of ischemia increasing or occurring at rest, 2) an elevated cardiac troponin I level (≥2.0 ng/mL) or troponin T level (≥0.1 ng/mL) or CK-MB (19 U/L, exceeding twice the upper limit of normal), and 3) ischemic changes assessed by electrocardiography, defined as ST-segment depression or T-wave inversion of ≥0.2 mV in two contiguous leads. Patients were excluded for having any of the following: STEMI; receiving fibrinolysis therapy; no data on glucose levels as soon as possible after admission and before the administration of any medication; bleeding history and thrombocytopenia; coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) within 1 month; drug allergy; anticoagulation contradiction; serum creatinine >2.5 mg/dL; malignancy; or neurological deficit that limited follow-up. All patients were treated according to standard guidelines with aspirin (300 mg of chewable preparation as a loading dose, followed by 100 mg/day), clopidogrel (300 mg as a loading dose and then 75 mg/day), and unfractionated heparin (5000 U as a loading dose and then 1000 U/kg/h with a partial thromboplastin time in the range of 50–70 s). CK-MB and troponin T or I were detected in all patients.

Date collection and variables

The following patient data were collected and analyzed: basic demographic and clinical characteristics (age, gender, hypertension, diabetes, smoker, hyperlipidemia, and pathological and therapeutic antecedents), clinical findings on admission, laboratory tests, echocardiographic changes, treatment during hospitalization, and treatment after discharge. The plasma glucose values and HbA1c levels of these patients were measured upon admission in the local laboratory at each participating center.

DM was defined as having a previous history of DM based on the medical institution standard diagnostic criteria, use of diet, oral glucose-lowering medication and/or insulin or a HbA1c ≥6.5%. This HbA1c value was recognized by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) as sufficient for the diagnosis of DM [14]. Hyperglycemia was defined as any in-hospital blood glucose measurement >140 mg/dL in accordance with the ADA consensus [15].

Admission hyperglycemia was defined as an APG concentration above the cut-off value, which discriminated between good and poor prognosis and varied over a wide range (between 6 mmol/L and 11 mmol/L) [16]. Previous studies found that the association between high APG levels and outcomes differed in individuals with and without DM [1, 3, 17, 18], and the prognostic cut-off is 144 mg/dL (8 mmol/L) for patients without DM and 180 mg/dL (10 mmol/L) for those with DM, as shown in the meta-analysis by Capes et al. [19]. Patients were divided into the following four groups: Groups 1 and 2, without DM and APG < or ≥144 mg/dL, respectively. Groups 3 and 4: with DM and APG < or ≥ 180 mg/dL.

Outcomes measured

The primary objective of the present study of NSTEMI patients undergoing PCI was to investigate the effect of APG levels on subsequent MACEs in these patients. A MACE was defined as any of the following: re-infarction; heart failure requiring admission; target vessel revascularization (TVR) for recurrent ischemia or acute occlusion of a stent; repeated PCI or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG); and stroke and mortality at the 30-day and 3-year follow-ups. The secondary purpose was to determine the optimal glucose cut-off values for predicting 30-day mortality in diabetic and non-diabetic NSTEMI patients undergoing PCI. Clinical follow-up variables, including re-infarction, heart failure requiring admission, and stroke and death data, were obtained from clinic visits and telephone interviews. Deaths were defined as vascular if the death certificate stated that the underlying cause of death was ischemic heart disease (I20-I25), stroke (I63, I64, and I67), or other vascular diseases (I70–I79), in accordance with the Tenth Revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10). Otherwise, deaths were defined as non-vascular.

All the patients were followed up at 30 days and 3 years after discharge. Clinical follow-up information was obtained by reviewing hospital records and conducting face-to-face interviews.

Statistical analyses

Continuous variables were described as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range), and differences among the groups were determined using Student’s t-test. Frequencies and proportions were reported for categorical variables and were compared using the chi-squared test. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was performed to identify the independent association between admission glycemia and MACEs at the 30-day or 3-year follow-ups. For all of the odds ratios (ORs), we calculated 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Kaplan–Meier methods were used to estimate the rates of cumulative occurrence of MACEs at the follow-up time points and to plot the time-to-cumulative occurrence of MACE curves. The significance of differences among the groups was determined using the log-rank test. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses were performed to establish the optimal cut-off values of APG for predicting 30-day mortality in patients with and without DM. All analyses were performed for the entire cohort, and the significance was established at the 0.05 level.

Results

Baseline characteristics

This study enrolled 890 patients, and 236 (26.5%) satisfied the criteria for DM. The median (interquartile range) APG levels were 133 (112–159) mg/dL for the entire cohort, 166 (138–202) mg/dL for patients with DM, and 124 (106–146) mg/dL for patients without diabetes.

There were no significant differences in mean age, prior myocardial infarction, prior CABG, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein, low-density lipoprotein, triglyceride, creatinine, number of vessels treated, and number of stents implanted in participants among the four groups (Table 1).

Compared with those of Group 1, Group 2 patients had a higher rate of Killip class 3–4, patients in Group 3 had significantly fewer women and smoking patients and more patients treated with oral hypoglycemic agent and insulin during hospitalization, and Group 4 patients had significantly higher prevalences of hypertension and hyperlipidemia, a higher rate of Killip class 3–4 and LVEF ≤40%, and were more likely to be treated with an oral hypoglycemic agent and insulin during hospitalization (Table 1). Compared with those of Group 2, more patients in Group 3 and Group 4 were treated with an oral hypoglycemic agent and insulin during hospitalization (Table 1). In addition, no significant differences were observed among these groups with regard to treatment with aspirin, ticlopidine and clopidogrel, beta-blockers, ACEI and ARB, statins, and CCB during hospitalization and follow-up (Table 1).

Influence of admission hyperglycemia on short-term MACEs

At 30 days after discharge, a higher APG was associated with significantly higher all-cause and cardiac mortality and heart failure requiring hospital admission, irrespective of diabetes status, but was not correlated with the differences in the non-cardiac mortality, rates of re-infarction, and ischemic TVR (Table 2). A significant association between the APG and rates of stroke after discharge was observed in patients without DM. In addition, the lowest early all-cause and cardiac mortality rates and the incidence of HF-required hospital admission and stroke were observed in the patients of Group 1 (i.e., without DM and APG <144 mg/dL), while the highest early all-cause and cardiac mortality rates and the incidence of HF-required hospital admission were observed in the patients of Group 4 (with DM and APG ≥180 mg/dL; Table 2).

Influence of admission hyperglycemia on long-term MACEs

An association between APG and MACEs was observed early after the acute event and remained stable through 3 years of follow-up (Table 2). Higher APG was associated with a significantly higher all-cause and cardiac mortality in patients irrespective of diabetes status, but was not associated with non-cardiac mortality or rates of ischemic TVR or stroke. In patients without DM, a significant association between APG and rates of re-infarction or heart failure requiring hospital admission was observed. The lowest late rates of all-cause and cardiac mortality re-infarction and heart failure requiring hospital admission and stroke were observed in Group 1 (without DM and APG <144 mg/dL), while the highest were observed in Group 4 (with DM and APG ≥180 mg/dL).

Survival analysis

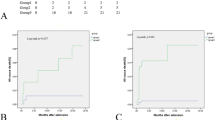

The Kaplan–Meier survival curves showed that, compared with Group 1 (without DM, APG <144 mg/dL), Group 2 (without DM, APG ≥144 mg/dL) patients had higher cumulative rates of MACEs at 30 days and 3 years (Fig. 1). Compared with those in Group 3 (DM, APG <180 mg/dL), patients in Group 4 (DM, APG ≥180 mg/dL) had higher cumulative MACE rates at 30 days and 3 years. When stratified by diabetes status and the APG levels, the highest 30-day and 3-year cumulative MACE rate was observed in Group 4, while the lowest was that of Group 1.

The 30-day (a) and 3-year (b) cumulative occurrence of MACEs for curves in NSTEMI patients undergoing PCI stratified according to diabetic status and admission plasma glucose (APG). Patients in Group 2 had higher cumulative occurrence rates of 30-day and 3-year MACEs. Patients in Group 4 had higher cumulative occurrence rates of 30-day and 3-year MACEs. Groups 1 and 2: without DM, APG <144 or ≥ 144 mg/dl. Groups 3 and 4: with DM, APG < or ≥ 180 mg/dl

Optimal cut-off values

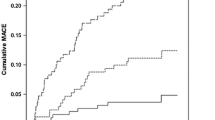

Multivariate analysis revealed that an elevated APG was an independent predictor of 30-day and 3-year MACEs, irrespective of diabetes status (Table 3). By the ROC analysis, the optimal cut-off values for predicting 30-day mortality were 157 mg/dL for the entire cohort; 145 mg/dL for patients without DM; and 178 mg/dL for patients with DM, with areas under the curve of 0.79, 0.76, and 0.71, respectively (Fig. 2).

Discussion

The present study investigated the APG as an indicator of the risk of short- and long-term MACEs in diabetic and non-diabetic NSTEMI patients undergoing PCI reperfusion. The analysis determined that, irrespective of diabetic status, APG could be used to predict 30-day and 3-year MACEs. Secondly, the predictive optimal admission hyperglycemia cut-off values for 30-day mortality were 157 mg/dL for all patients (area under the curve [AUC], 0.79), 178 mg/dL for those with DM (AUC, 0.71), and 145 mg/dL for patients without DM (AUC, 0.76).

Hyperglycemia on admission has been considered an acute stress response [20, 21], particularly in STEMI patients with severe left ventricular dysfunction [22]. Some studies purport that hyperglycemia on admission is causally linked to poor outcomes after AMI or is simply an epiphenomenon related to the severity of disease. Most recent studies have reported that admission hyperglycemia after AMI is causally linked to further deterioration due to myocardial damage and increased risk of death in patients, with or without diabetes. [1–9, 12]. Yet, the clinical and prognostic significance of high APG levels have differed between STEMI and NSTEMI patients [8]. Since several similar studies have been conducted on STEMI patients [2, 4, 5], our study focused on NSTEMI patients undergoing PCI, to explore the effects of APG on the rate of after hospital discharge, and its prognostic value in the absence or presence of DM.

The mechanisms by which hyperglycemia causes unfavorable effects in patients with AMI are not understood well. However, several studies have suggested that a wide variety of pathophysiologic changes linked to hyperglycemia contribute to increased mortality and morbidity rates. It is notable that acute hyperglycemia may exert significant hemodynamic effects even in normal subjects. A previous study showed that plasma glucose levels maintained at 15.0 mmol/L for 2 h in healthy subjects significantly increased the mean heart rate (+9 beats per minute), systolic and diastolic blood pressures (+20 and +14 mmHg, respectively), and plasma catecholamine levels. These hemodynamic effects were abolished by glutathione, a widely recognized free radical scavenger [23], suggesting that these changes were mediated by an oxidative-linked mechanism [24].

Stress hyperglycemia after AMI has been be associated with endothelial and microvascular dysfunction induced by oxidative stress and amplified inflammatory immune reactions. Esposito et al. [25] found that circulating inflammatory cytokine levels closely correlated with plasma glucose levels, that is, increasing as plasma glucose levels increased, and immediately returning to normal as the plasma glucose level decreased to normal. Increased serum inflammatory cytokine concentrations may intensify oxidative stress and further damage endothelial function, while reductions in circulating levels of inflammatory cytokines were accompanied by improved endothelial function [26].

In addition, some studies have suggested that the prothrombotic state generated by hyperglycemia reduces plasma fibrinolytic activity and activated tissue plasminogen [27]. Through these mechanisms, stress hyperglycemia after AMI is closely linked to impaired myocytes [27, 28], impaired left ventricular function and exacerbated cardiac damage induced by acute ischemia/reperfusion injury [29].

In conclusion, acute hyperglycemia induced by oxidative stress, inflammation, apoptosis, endothelial dysfunction, hypercoagulation, platelet aggregation, and impairment of ischemic preconditioning damages the ischemic myocardium. In the present study, an APG >140 mg/dL (7.8 mmol/L) was defined as admission hyperglycemia in accordance with the 2013 ADA Standard of Medical Care criteria 15, which were determined based on a number of large scale studies of the effect of glucose levels on mortality [30–33]. Our study confirmed that APG scores positively correlated with rates of MACEs in both diabetic and non-diabetic patients.

Our study also determined the optimal cut-off APG value for predicting short-term mortality in NSTEMI patients undergoing PCI. For assessing prognosis, stress hyperglycemia can be defined as an APG above the cut-off value. Such a cut-off value, determined via a ROC curve, should differentiate patients who achieve an uneventful recovery from those with poor outcomes during the observation period. In addition, for AMI patients with DM, the prognostic cut-off value for hyperglycemia on admission should not be the same as for non-diabetic AMI patients, because the former have a higher average blood glucose level [34]. Indeed, we found in the present study that 178 mg/dL was the optimal cut-off point for patients with DM and 145 mg/dL for the patients without DM. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to analyze separately the optimal cut-off APGs for NSTEMI patients with and without DM, to predict short-term mortality. Finally, our results suggest that elevated glucose levels may be an important biomarker of increased MACEs in both diabetic and non-diabetic patients.

Study limitations

The statistical power of the present study was limited by the small number of patients in some of the groups. Also, we were not able to collect data regarding liver failure, obesity, physical activity, inflammatory markers, or socioeconomic status, and therefore, we were not able to adjust the analysis for these potential confounders. Finally, although herein we reveal that hyperglycemia on admission was associated with unfavorable short- and long-term outcomes of both diabetic and non-diabetic NSTEMI patients undergoing PCI treatment, the effects of treating hyperglycemia after admission were not assessed. Our results warrant corroboration with a study of larger scale.

Conclusions

An elevated APG level, regardless of the diagnosis of diabetes, results in higher short-term and long-term poor outcomes in patients with NSTEMI undergoing PCI. The optimal cut-off values for blood glucose in the prognosis of patients with and without DM are different.

Abbreviations

- ACEI:

-

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor

- ADA:

-

American Diabetes Association

- AMI:

-

Acute myocardial infarction

- APG:

-

Admission plasma glucose level

- ARB:

-

Angiotensin receptor blocker

- AUC:

-

Area under curve

- CABG:

-

Coronary artery bypass grafting

- CAD:

-

Coronary artery disease

- CCB:

-

CALCIUM channel blocker

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CK-MB:

-

Creatine kinase-myocardial band

- cTnI:

-

Cardiac troponin I

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- ECG:

-

Electrocardiograph

- HDL:

-

High density lipoprotein

- HF:

-

Heart failure

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- LAD:

-

Left anterior descending

- LDL:

-

Low density lipoprotein

- LM:

-

Left main coronary artery

- LVEF:

-

Left-ventricular ejection fraction

- MACEs:

-

Major adverse cardiac events

- MI:

-

Myocardial infarction

- NSTEMI:

-

Non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction

- OR:

-

Odds ratios

- PCI:

-

Percutaneous coronary intervention

- ROC:

-

Receiver operator characteristic

- RR:

-

Relative risk

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- STEMI:

-

ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

- TC:

-

Serum total cholesterol

- TG:

-

Triglyceride

- TIMI:

-

Thrombolysis in myocardial infarction

- TVR:

-

Target vessel revascularization

References

Kosiborod M, Rathore SS, Inzucchi SE, Masoudi FA, Wang Y, Havranek EP, Krumholz HM. Admission glucose and mortality in elderly patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction: implications for patients with and without recognized diabetes. Circulation. 2005;111(23):3078–86.

Li DB, Hua Q, Guo J, Li HW, Chen H, Zhao SM. Admission glucose level and in-hospital outcomes in diabetic and non-diabetic patients with ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction. Intern Med. 2011;50(21):2471–5.

Stranders I, Diamant M, van Gelder RE, Spruijt HJ, Twisk JW, Heine RJ, Visser FC. Admission blood glucose level as risk indicator of death after myocardial infarction in patients with and without diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(9):982–8.

Chen PC, Chua SK, Hung HF, Huang CY, Lin CM, Lai SM, Chen YL, Cheng JJ, Chiu CZ, Lee SH, Lo HM, Shyu KG. Admission hyperglycemia predicts poorer short- and long-term outcomes after primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-elevation myocardial infarction. J Diabetes Investig. 2014;5(1):80–6.

Pinto DS, Kirtane AJ, Pride YB, Murphy SA, Sabatine MS, Cannon CP, Gibson CM, Investigators C-T. Association of blood glucose with angiographic and clinical outcomes among patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (from the CLARITY-TIMI-28 study). Am J Cardiol. 2008;101(3):303–7.

Norhammar A, Tenerz A, Nilsson G, Hamsten A, Efendic S, Ryden L, Malmberg K. Glucose metabolism in patients with acute myocardial infarction and no previous diagnosis of diabetes mellitus: a prospective study. Lancet. 2002;359(9324):2140–4.

Svensson AM, McGuire DK, Abrahamsson P, Dellborg M. Association between hyper- and hypoglycaemia and 2 year all-cause mortality risk in diabetic patients with acute coronary events. Eur Heart J. 2005;26(13):1255–61.

Ji MS, Jeong MH, Ahn YK, Kim YJ, Chae SC, Hong TJ, Seong IW, Chae JK, Kim CJ, Cho MC, Rha SW, Bae JH, Seung KB, Park SJ. Impact of low level of high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol sampled in overnight fasting state on the clinical outcomes in patients with acute myocardial infarction (difference between ST-segment and non-ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction). J Cardiol. 2015;65(1):63–70.

Goyal A, Mehta SR, Diaz R, Gerstein HC, Afzal R, Xavier D, Liu L, Pais P, Yusuf S. Differential clinical outcomes associated with hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia in acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2009;120(24):2429–37.

Pres D, Gasior M, Strojek K, Gierlotka M, Hawranek M, Lekston A, Wilczek K, Tajstra M, Gumprecht J, Polonski L. Blood glucose level on admission determines in-hospital and long-term mortality in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock treated with percutaneous coronary intervention. Kardiol Pol. 2010;68(7):743–51.

Savonitto S, Morici N, Cavallini C, Antonicelli R, Petronio AS, Murena E, Olivari Z, Steffenino G, Bonechi F, Mafrici A, Toso A, Piscione F, Bolognese L, De Servi S. One-year mortality in elderly adults with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome: effect of diabetic status and admission hyperglycemia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(7):1297–303.

Planer D, Witzenbichler B, Guagliumi G, Peruga JZ, Brodie BR, Xu K, Fahy M, Mehran R, Stone GW. Impact of hyperglycemia in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: the HORIZONS-AMI trial. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167(6):2572–9.

Timmer JR, van der Horst IC, Ottervanger JP, Henriques JP, Hoorntje JC, de Boer MJ, Suryapranata H, Zijlstra F. Zwolle myocardial infarction study G. Prognostic value of admission glucose in non-diabetic patients with myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2004;148(3):399–404.

American DA. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2012;35 Suppl 1:S64–71.

American DA. Standards of medical care in diabetes--2013. Diabetes Care. 2013;36 Suppl 1:S11–66.

Ishihara M. Acute hyperglycemia in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circ J. 2012;76(3):563–71.

Goyal A, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, Nicolau JC, Hochman JS, Weaver WD, Theroux P, Oliveira GB, Todaro TG, Mojcik CF, Armstrong PW, Granger CB. Prognostic significance of the change in glucose level in the first 24 h after acute myocardial infarction: results from the CARDINAL study. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(11):1289–97.

Kosiborod M, Inzucchi SE, Krumholz HM, Xiao L, Jones PG, Fiske S, Masoudi FA, Marso SP, Spertus JA. Glucometrics in patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction: defining the optimal outcomes-based measure of risk. Circulation. 2008;117(8):1018–27.

Capes SE, Hunt D, Malmberg K, Gerstein HC. Stress hyperglycaemia and increased risk of death after myocardial infarction in patients with and without diabetes: a systematic overview. Lancet. 2000;355(9206):773–8.

Donahoe SM, Stewart GC, McCabe CH, Mohanavelu S, Murphy SA, Cannon CP, Antman EM. Diabetes and mortality following acute coronary syndromes. JAMA. 2007;298(7):765–75.

Hasin T, Hochadel M, Gitt AK, Behar S, Bueno H, Hasin Y. Comparison of treatment and outcome of acute coronary syndrome in patients with versus patients without diabetes mellitus. Am J Cardiol. 2009;103(6):772–8.

De Caterina R, Madonna R, Sourij H, Wascher T. Glycaemic control in acute coronary syndromes: prognostic value and therapeutic options. Eur Heart J. 2010;31(13):1557–64.

Galano A, Alvarez-Idaboy JR. Glutathione: mechanism and kinetics of its non-enzymatic defense action against free radicals. RSC Adv. 2011;1:1763–71.

Marfella R, Verrazzo G, Acampora R, La Marca C, Giunta R, Lucarelli C, Paolisso G, Ceriello A, Giugliano D. Glutathione reverses systemic hemodynamic changes induced by acute hyperglycemia in healthy subjects. Am J Physiol. 1995;268(6 Pt 1):E1167–73.

Esposito K, Nappo F, Marfella R, Giugliano G, Giugliano F, Ciotola M, Quagliaro L, Ceriello A, Giugliano D. Inflammatory cytokine concentrations are acutely increased by hyperglycemia in humans: role of oxidative stress. Circulation. 2002;106(16):2067–72.

Rioufol G, Finet G, Ginon I, Andre-Fouet X, Rossi R, Vialle E, Desjoyaux E, Convert G, Huret JF, Tabib A. Multiple atherosclerotic plaque rupture in acute coronary syndrome: a three-vessel intravascular ultrasound study. Circulation. 2002;106(7):804–8.

Pandolfi A, Giaccari A, Cilli C, Alberta MM, Morviducci L, De Filippis EA, Buongiorno A, Pellegrini G, Capani F, Consoli A. Acute hyperglycemia and acute hyperinsulinemia decrease plasma fibrinolytic activity and increase plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 in the rat. Acta Diabetol. 2001;38(2):71–6.

Ceriello A. Acute hyperglycaemia: a ‘new’ risk factor during myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2005;26(4):328–31.

Frantz S, Calvillo L, Tillmanns J, Elbing I, Dienesch C, Bischoff H, Ertl G, Bauersachs J. Repetitive postprandial hyperglycemia increases cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury: prevention by the alpha-glucosidase inhibitor acarbose. FASEB J. 2005;19(6):591–3.

Chen JH, Tseng CL, Tsai SH, Chiu WT. Initial serum glucose level and white blood cell predict ventricular arrhythmia after first acute myocardial infarction. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28(4):418–23.

Lonborg J, Vejlstrup N, Kelbaek H, Nepper-Christensen L, Jorgensen E, Helqvist S, Holmvang L, Saunamaki K, Botker HE, Kim WY, Clemmensen P, Treiman M, Engstrom T. Impact of acute hyperglycemia on myocardial infarct size, area at risk, and salvage in patients with STEMI and the association with exenatide treatment: results from a randomized study. Diabetes. 2014;63(7):2474–85.

Timoteo AT, Papoila AL, Rio P, Miranda F, Ferreira ML, Ferreira RC. Prognostic impact of admission blood glucose for all-cause mortality in patients with acute coronary syndromes: added value on top of GRACE risk score. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2014;3(3):257–63.

Koracevic GP, Petrovic S, Damjanovic M, Stanojlovic T. Association of stress hyperglycemia and atrial fibrillation in myocardial infarction. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2008;120(13–14):409–13.

Deedwania P, Kosiborod M, Barrett E, Ceriello A, Isley W, Mazzone T, Raskin P. American Heart Association Diabetes Committee of the council on nutrition PA, metabolism. Hyperglycemia and acute coronary syndrome: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Diabetes Committee of the Council on nutrition, physical activity, and metabolism. Circulation. 2008;117(12):1610–9.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This study was supported by Science and Technology Program for Public Wellbeing (2012GS610101 to AM) and Shaanxi Science & Technology Co-ordination & Innovation Project (2012KTCQ03-05 to AM), which played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Author contributions

YH Conceived of the study, participated in its design, collected the patient data, performed the statistical analysis, and drafted the manuscript. QL Participated in the study design and statistical analyses. TL, GY and PH Collected the patient data. AM Conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination, and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

None.

Consent for publication

Consent to publish was obtained from all participants.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethics Committee of First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University approved this retrospective study, and all participants signed informed consent forms.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Hao, Y., Lu, Q., Li, T. et al. Admission hyperglycemia and adverse outcomes in diabetic and non-diabetic patients with non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 17, 6 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-016-0441-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-016-0441-x