Abstract

Background

Several plants are facing drought stress due to climate change in recent years. In this study, we aimed to explore the effect of varying watering frequency on the growth and photosynthetic characteristics of Hosta ‘Guacamole’. Moreover, we investigated the effect of high-nitrogen and -potassium fertilizers on alleviating the impacts of drought stress on the morphology, photosynthetic characteristics, chlorophyll fluorescence, fast chlorophyll a fluorescence transient, JIP-test parameters, and enzymatic and non-enzymatic scavenging system for reactive oxygen species (ROS) in this species.

Results

Leaf senescence, decreased chlorophyll contents, limited leaf area, and reduced photosynthetic characteristics and oxygen-evolving complex (OEC) activity were observed in Hosta ‘Guacamole’ under drought stress. However, high-nitrogen fertilizer (30-10-10) could efficiently alleviate and prevent the adverse effects of drought stress. High-nitrogen fertilizer significantly increased chlorophyll contents, which was higher by 106% than drought stress. Additionally, high-nitrogen fertilizer significantly improved net photosynthetic rate and water use efficiency, which were higher by 467% and 2900% than those under drought stress. It attributes that high-nitrogen fertilizer could reduce transpiration rate of leaf cells and stomatal opening size in drought stress. On the other hand, high-nitrogen fertilizer enhanced actual photochemical efficiency of PS II and photochemical quenching coefficient, and actual photochemical efficiency of PS II significantly higher by 177% than that under drought stress. Furthermore, high-nitrogen fertilizer significantly activated OEC and ascorbate peroxidase activities, and enhanced the performance of photosystem II and photosynthetic capacity compared with high-potassium fertilizers (15-10-30).

Conclusions

High-nitrogen fertilizer (30-10-10) could efficiently alleviate the adverse effects of drought stress in Hosta ‘Guacamole’ via enhancing OEC activity and photosynthetic performance and stimulating enzymatic ROS scavenging system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

Water scarcity is one of the main consequences of climate change caused by global warming and has created abiotic stress environment for a huge number of plants [1]. Drought stress affects plant physiology and metabolism and negatively affects plant growth, stomatal conductance, gas exchange, chlorophyll content, leaf water potential, and photosynthesis [2,3,4]. Drought in summer often results in the morphological changes in plants such as yellowing, curling, and wilting of leaves and reduces the yield and ornamental value of commercial crops and ornamental plants [5, 6].

Hosta species (family: Liliaceae) are herbaceous perennials, which are commercially grown on a large scale for landscaping and for extracting essential oil in many countries [7]. Various members of Hosta spp. have varying sizes, from miniature to giant, and they are native to China, Japan, and Korea. Most endemic species are used as edible vegetables and folk medicines [6]. Previous studies reported that Hosta spp. is rich in steroids and flavonoids with valuable medicinal properties such as anti-inflammatory, analgesic, antioxidant, antitumor, antiviral, acetylcholinesterase inhibitory, antimicrobial, and anti-chronic-prostatitis [8]. Moreover, flowers of several members of this species have attractive fragrance, with the main aromatic compound being terpenoids (mainly myrcene, limonene, beta-ocimene, and linalool) [9, 10]. Compared with the cultivar, the most characteristic aromatic compound in wild-type Hosta flowers was reported to be hexanol. The essential oil obtained from wild-type H. sieboldiana flowers was richer in aromatic compounds than that obtained from the cultivar flowers, highlighting the use of wild-type flowers for essential oil extraction [11]. In addition, it is considered a decorative plant because of delicate flowers and because its leaves are of varying sizes, shapes, and colors [12]. Hosta spp. has a high ornamental value in gardening industry. The flowers of most members of Hosta spp. exhibit colors in the shades of purple and white. Their leaves may be green, blue, yellow, golden, or white and may have one or multiple colors [12]. For example, H. plantaginea is used for landscaping and gardening and is appreciated for its ornamental value with beautiful foliage and flowers, as well as long blooming period [8, 13].

Previous studies revealed that various environmental factors affect the growth and photosynthetic capacity of various members of Hosta spp [14,15,16]. It is essential to conserve water during cultivation and avoid morphological changes that can occur in Hosta spp. after being in water-deficient environment for a long time [14]. In the view of severe global climate change, increased temperature in summer and reduced rainfall are being observed in China and globally [17]. Severe environmental stresses such as drought stress would affect photosystem II (PS II) in plants [18]. Previous studies reported that the application of growth hormones, silicon, or selenium or molecular and genomic breeding for drought resistance could alleviate the adverse effects of drought stress [3, 4]. However, they have weak operability, hampering its practical use. However, salicylic acid and nitrogen and potassium fertilizers could also alleviate the effects of drought stress in plants [19, 20]. Therefore, the application of fertilizers perhaps is the most convenient and easy way to resist drought stress.

Breeding fragrant cultivars has become the new trend of modern development of Hosta [10]. Hosta ‘Guacamole’ is an aromatic and ornamental herb and is a Hosta hybrid cultivar. Its white flowers have characteristic fragrance and can be used to extract essential oil. Its leaves lack wax coat; therefore, they are perhaps sensitive to temperature, light, and moisture compared with other members of Hosta spp. with wax coat. In this study, we aimed to explore the effect of drought stress on the growth and photosynthetic characteristics of Hosta ‘Guacamole’ and to further analyze high-nitrogen fertilizers how to alleviate the adverse effects of drought stress. This study provided an effective method to solve the problem of decreasing yield and ornamental value of Hosta spp. under drought and provided the theoretical basis for alleviating the adverse effects of drought stress. In addition, our study provided a basis for the cultivation of Hosta spp. in the view of climate change.

Results

Effect of high-nitrogen and -potassium fertilizers on the morphological characteristics of Hosta ‘Guacamole’ under drought stress

The morphology of plants under T3 treatment in drought stress was clearly different. The edges of leaves gradually started turning white (Fig. 1A), and later, the edge of leaves the entire leaf surface turned white under T4 treatment (Fig. 1B). After the fertilizer treatment in T5 and T6, the leaves turned green and had more leaves than T4 (Fig. 1B; Table 1). Under T3, the size of stomatal opening was smaller by 51.8% and 36.3% than that under T1 and T2, respectively (Fig. 1C-E). However, T4, T5, and T6 treatments resulted in smaller and even closure of stomatal opening in longtime drought environment (Fig. 1F-H).

The largest leaf area was under T1, which was higher by 16.7% and 18.7% than that under T2 and T3, respectively. The L* and b* values under T3 treatment were clearly higher by 3.9% and 5.9% than those under T1, respectively. The lowest chlorophyll content was observed under T3, which was lower by 15.6% and 21.0% than that under T1 and T2, respectively. After fertilizer treatment to T3-treated plants, under T5 and T6, the leaf area clearly increased; the largest leaf area was 78.4 ± 5.92a cm2 under T5. In addition, under T5 and T6, the chlorophyll content of leaves substantially increased, alleviating the yellowing of the leaves. The highest chlorophyll content was in T5, which was significantly higher 106% than those T4. The L* and b* values were significantly lower and a* value was significantly higher under T5 than under T4 and T6 (Table 1).

Effect of high-nitrogen and -potassium fertilizers on the photosynthetic characteristics of Hosta ‘Guacamole’ under drought stress

The maximum net photosynthetic rate (Pn), stomatal conductance (gs), and transpiration rate (Tr) were observed in T1 and T2 compared with T3. However, compared with T1 and T2, T3 treatment exhibited the maximum vapor pressure deficit (VPD). The intercellular CO2 concentrations (Ci) and water use efficiency (WUE) were not significantly different among the treatments. After various fertilizer treatments, the Pn and WUE under T5 were significantly higher than those under T4 and T6. The Pn under T5 was 4.45 ± 1.20a µmol m− 2 s− 1, which was significantly higher by 467% than that under T4. However, the gs, Tr, and Ci under T4 were significantly higher by 417%, 710%, and 329%, than those under T5, respectively, but no significant difference was observed in terms of VPD (Fig. 2).

The effect of high-nitrogen and -potassium fertilizers on the Pn (A), Ci (B), gs (C), Tr (D), VPD (E), and WUE (F) of Hosta ‘Guacamole’ under drought stress. Each value is expressed as the mean ± SE of 9 independent plants. Different lowercase letters represent significant differences between treatments (P < 0.05)

Effect of high-nitrogen and -potassium fertilizers on the chlorophyll fluorescence in Hosta ‘Guacamole’ under drought stress

The actual photochemical efficiency of PS II (ΦPS II) and electron transport rate (ETR) were increased as the water content in soil increased. The highest ETR and ΦPS II were observed under T1. The lowest ΦPS II was observed under T3. The lowest ETR and photochemical quenching coefficient (qP) were observed under T3. The highest non-photochemical quenching coefficient (NPQ) was observed under T2 and T3.

After fertilizer treatments, the ΦPS II, ETR, and qP were significantly increased under T5 and T6, exhibiting the maximum value under T5. These values under T5 were 0.539 ± 0.014a, 23.4 ± 1.31a, and 0.822 ± 0.069a, respectively, and were higher by 177%, 191%, and 90.0%, respectively, than those under T4. Conversely, the NPQ exhibited the minimum value under T5 (0.209 ± 0.061b), which was significantly lower than that under T4 and T6 (Fig. 3).

The effect of high-nitrogen and potassium fertilizers on the ΦPS II (A), ETR (B), qP (C), and NPQ (D) in Hosta ‘Guacamole’ under drought stress. Each value is expressed as the mean ± SE of 3 independent plants, and each treatment was repeated four times. Different lowercase letters represent significant differences between treatments (P < 0.05)

Effect of high-nitrogen and -potassium fertilizers on the chlorophyll fluorescence rise kinetics in Hosta ‘Guacamole’ under drought stress

The chlorophyll fluorescence characteristics of Hosta ‘Guacamole’ were further analyzed. The chlorophyll fluorescence was higher under T3 than under T1 and T2 in OJIP curve (Fig. 4A). However, it was clearly lower under T5 and T6 than under T4 in OJIP curve (Fig. 4B). In ΔWOK analysis, the highest ΔWL under T3 was 1.10 ± 0.324a which was significantly higher than that under T1 and T2. On the other hand, it was significantly lower by 46.1% and 42.6%, respectively, under T5 and T6 than that under T4 (Fig. 5A and B). In ΔWOJ analysis, ΔWK was clearly higher by 58.8% and 58.6%, respectively, in T3 than that in T1 and T2 (Fig. 6A). However, after fertilizer treatments, in T5 and T6, the ΔWK value was significantly lower by 46.4% and 68.2%, respectively, than that in T4 (Fig. 6B).

We further analyzed the oxygen-evolving complex (OEC) activity under T1–3. The OEC center activity was significantly lower in T3 than in T1 and T2. The OEC center activity was only 0.309 ± 0.136b; this was attributed to drought stress in T3 (Fig. 7A). However, under T5 and T6, the OEC center activity was significantly higher by 812% and 683%, respectively, than that under T4. The maximum OEC center activity was observed in T5 (Fig. 7B).

Effect of high-nitrogen and potassium fertilizers on the JIP-test parameters in Hosta ‘Guacamole’ under drought stress

The JIP-test parameters of Hosta ‘Guacamole’ were different under various treatments (Fig. 8). The performance index for the conservation of energy from photons absorbed by the PS II antenna to the reduction of PS I acceptors (PItotal), maximum quantum yield of primary photochemistry (Fv/Fm), quantum yield of the electron transport flux from QA to QB (φEo), and quantum yield of the electron transport flux until the PS I electron acceptors (φRo) were significantly lower in T3 than in T1 and T2. The PItotal was significantly lower by 71.6% and 64.7% in T3 than in T1 and T2, respectively. No significant differences in other JIP-test parameters including electron transport efficiency from QA− to the PSI electron end acceptors (ψEo), electron transport efficiency except QA (ψRo), and efficiency with which an electron from QB is transferred until PSI acceptors (δRo) were observed among the treatments (Fig. 8A). All the JIP-test parameters were higher under T5 and T6 than under T4. The maximum value of PItotal and ψRo was observed under T5 treatment, which was significantly higher by 1725% and 10.7%, respectively, in T5 than in T4 (Fig. 8B).

The alleviating effect of high-nitrogen and potassium fertilizers on the impacts of drought stress in Hosta ‘Guacamole’ in terms of reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenging

The ROS are scavenged by ascorbate peroxidase (APX), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and non-enzymatic antioxidants such as glutathione (GSH). The APX activity was the highest in T5 (4.43 ± 0.133a U·g− 1), which was higher by 44.1% and 46.9% than that in T4 and T6, respectively (Fig. 9A). The highest SOD activity (55.9 ± 2.68a U·g− 1) and GSH content (294 ± 3.54a µg·g− 1) were observed under T4. In non-enzymatic ROS scavenging system, GSH level was significantly higher by 15.3% and 19.7% in T4 than in T5 and T6, respectively. In enzymatic ROS scavenging system, the SOD activity was significantly higher by 368% and 274% in T4 than in T5 and T6, respectively (Fig. 9B, C).

Discussion

High-nitrogen fertilizer could avoid morphological changes of Hosta ‘Guacamole’ under drought stress

The frequency and severity of drought is expected to increase due to climate change [21]. Several plants are facing drought stress and high-temperature stress due to climate change; this has resulted in morphological changes including dehydrated, discolored, curled, and burned leaves [5, 6]. Thus, studying the response of Hosta plants to drought stress may help to design strategies for improving drought tolerance in Hosta ‘Guacamole’ and to efficiently deal with morphological changes due to drought stress. This study aimed to provide a basis and theoretical guidance for cultivating ornamental and horticultural plants with tolerance to drought stress. Previous studies reported that salicylic acid and sufficient nitrogen supplementation could increase leaf area under drought stress [19, 20] and efficiently improve relative water and chlorophyll contents and leaf area [8, 22]. Therefore, nitrogen fertilizer can play an important role in alleviating the effects of drought stress in plants. In this study, Hosta ‘Guacamole’ with water shortage (T3) exhibited growth with smaller leaf area and withering from the edge to center of leaves. However, water-soluble fertilizer, particularly high-nitrogen fertilizer, efficiently alleviated the effects of drought stress in Hosta ‘Guacamole’ in summer. In our results, high-nitrogen fertilizer treatment resulted in larger leaf area and greener and smoother leaves under drought stress. Furthermore, stomatal opening was smaller, transpiration rate decreased, and WUE was clearly improved, which avoided the loss of water inside the cells in drought environment. Therefore, this indicated that high-nitrogen fertilizer could avoid morphological changes under drought stress in summer.

High-nitrogen fertilizer could improve the photosynthetic characteristics of Hosta ‘Guacamole’ under drought stress

Drought stress not only affects plant morphology but also changes the photosynthetic characteristics of plant leaves, which are sensitive to high temperature and drought [23]. Previous studies reported that the net photosynthesis rate, stomatic conductance, and transpiration rate were reduced in response to drought stress [24]. Similarly, our results concluded that drought stress significantly negatively affected the photosynthetic characteristics. Meanwhile, previous studies reported that salicylic acid can effectively increase photosynthesis of mustard plants under drought stress with sufficient nitrogen supplementation [20]. In our study, in the high-nitrogen treatment T5, the net photosynthetic rate and WUE were significantly enhanced and stomatal conductance and transpiration rate were decreased. T5 exhibited the highest WUE and lowest transpiration rate under drought stress, effectively enhancing the ability of drought stress resistance [22]. However, T4 (water shortage) exhibited lower Pn, Gs, and Tr and higher Ci than T5 and T6, which was mainly caused by stomatal closure and complex non-gassing effects [25]. In our study, high-nitrogen fertilizer could efficiently alleviate the adverse effects of drought stress in Hosta ‘Guacamole’ by reducing transpiration rate of leaf cells and stomatal opening size, increasing WUE, and further efficiently enhancing the photosynthetic rate.

High-nitrogen fertilizer could improve chlorophyll fluorescence and photochemical efficiency in Hosta ‘Guacamole’ under drought stress

The physiological and biochemical parameters of plants under stress can be nondestructively monitored using hyperspectral imaging systems measuring chlorophyll fluorescence [8]. In our study, the ΦPS II, ETR, and qP were significantly higher in T1 than in T3, indicating that T3 resulted in photoinhibition and decreased the photochemical efficiency of Hosta ‘Guacamole’ plants under drought stress [26]. However, T5 and T6 alleviated the photoinhibition and improved the photochemical efficiency caused by drought stress; thus, they significantly enhanced the actual photochemical efficiency of PS II, photochemical quenching coefficient, and electron transport rate. The photochemical quenching coefficient NPQ provides insights on the level of overexcitation energy and protects photosystems from this energy by releasing heat [27]. In our study, the NPQ was significantly lower in T1 than in T2 and T3, which indicated that drought stress mainly decreased photochemical efficiency and enhanced heat-dissipation pathway in Hosta ‘Guacamole’. However, the NPQ was significantly lower in T5 than in T4 and T6, suggesting that high-nitrogen fertilizer efficiently alleviated photoinhibition under drought stress and enhanced the photochemical efficiency for photosystems rather than regulating heat dissipation [28].

To further understand the effect of drought stress on photosynthesis in Hosta ‘Guacamole’, the measurement and analysis of fast chlorophyll a fluorescence is a useful and efficient method for the assessment of many external or intrinsic adverse effects on PS II photochemistry [29]. In OJIP curve, the positive ΔL-, ΔK-, ΔJ-, and ΔI-bands appeared in T3, indicating that drought stress perhaps resulted in uncoupling of the OEC, accumulation of QA−, or destroying the acceptor side of PS II [26]. In T3, the L-band was positive in ΔWOK with bigger amplitude, and the ΔWL value was significantly higher than that in T1 and T2. This indicated that T3 lost more PS II energetic connectivity, which resulted in more sensitivity to drought stress [30]. In addition, the K-band was positive in ΔWOJ, and the ΔWL value was significantly higher in T3 than in T1 and T2, which was attributed to the damage on the OEC at the PS II donor side [31]. Furthermore, our results confirmed the possibility that the OEC activity of T3 was significantly lower than that of T1 and T2, which perhaps generated more H2O2 and destroyed cell structure [32]. However, the treatment with water-soluble high-nitrogen (T5) and high-potassium (T6) alleviated the negative effects of drought stress in the photosynthetic system. T5 and T6, particularly T5, efficiently improved PS II energetic connectivity and enhanced the OEC activity of the reaction center, which could efficiently avoid cell damage [33, 34].

Furthermore, our results revealed that the JIP-test parameters, particularly, PI total, Fv/Fm, φEo, and φRo, which quantified the conformation, structure, and function of photosynthetic apparatus, were significantly lower in T3 than in T1 and T2 treatments [30]. It indicated that drought stress resulted in the inhibition of performance index PItotal and quantum yield of the electron transport flux (φEo and φRo) [31]. However, drought stress did not affect the electron transport (ψEo, ψRo, and δRo) of the photosynthetic apparatus. It indicated that the photosynthetic apparatus was different in T3, which could be attributed to the inhibition of light reactions, OEC inactivation, and reduction of chlorophyll content [31, 35]. T5 and T6 efficiently alleviated the photosynthetic apparatus stress and enhanced performance index, photosynthetic capacity, and electron transport under drought stress. T5 exhibited better alleviation and resistance effects in Hosta ‘Guacamole’ under drought stress and could more efficiently enhance PS II performance and PS II capacity [31]. This was attributed to the enhanced OEC activity and PS II performance by nitrogen fertilizer.

High-nitrogen fertilizer could improve drought resistance of Hosta ‘Guacamole’ by stimulating enzymatic ROS scavenging system

Prolonged exposure to extreme conditions results in the increased accumulation of ROS, which easily results in lipid peroxidation and cellular damage [36]. H2O2 is an ROS that can translocate to the nucleus and acts as a signaling agent. Moreover, O2− is very harmful and identified as the cause of photooxidative damage in plant leaves [36]. Meanwhile, OEC-depleted PS II predominantly generates H2O2 [32]. The balance of ROS in plant cells is important for plant development. The antioxidant defense system in the plant cell includes both enzymatic (e.g., SOD) and nonenzymatic (e.g., ascorbate, GSH, and α-tocopherol) antioxidants [37]. The enzymatic ROS scavenging system in plant cells includes enzymes such as SOD, POD, CAT, and APX. In the ascorbate–glutathione cycle, APX reduces H2O2 using ascorbate as an electron donor, which plays a crucial role in controlling the level of toxic byproducts of aerobic metabolism [38]. In the nonenzymatic ROS scavenging system, GSH acts as an antioxidant to reduce oxidative stress. Increased content of GSH is responsible for the reduction of oxidative stress, which plays a role in ROS detoxification, either directly or indirectly [20]. It is widely accepted that drought affects plant growth and development, changes the accumulation of compatible solutes and protective enzymes, enhances the levels of antioxidants, and inhibits energy-consuming pathways [26]. In our study, the SOD and GSH levels were significantly higher in T4 than in T5 and T6. This indicated that in Hosta ‘Guacamole’, the nonenazymatic ROS scavenging system was activated under drought stress to reduce damage due to ROS. However, high-nitrogen fertilizer treatment also activated enzymatic ROS scavenging system, as reflected by high APX activity and decreased ROS accumulation, which played an important role in decreasing toxic byproducts of aerobic metabolism in Hosta ‘Guacamole’. Our results indicated that high-nitrogen fertilizer improved drought resistance in Hosta ‘Guacamole’ by stimulating enzymatic ROS scavenging system. In conclusion, in summer, water-soluble fertilizer treatment to Hosta ‘Guacamole’ could efficiently alleviate the adverse effects of drought stress and improve drought resistance, with high-nitrogen (30-10-10).

Fertilizer exhibiting the best effect in alleviating drought stress. The drought resistance mechanism of Hosta ‘Guacamole’ under high-nitrogen fertilizer treatment will be further studied by studying the transcriptome and metabolome. However, we only concentrated on the effect of high-nitrogen fertilizer on Hosta ‘Guacamole’ under drought stress in this study, and similar experiment can be conducted on other plants in future to assess the effect of nitrogen fertilizer under drought stress.

Conclusion

In this study, watering for once in 2 weeks in summer resulted in drought stress in Hosta ‘Guacamole’, causing leaf senescence, decreased chlorophyll content, limited leaf area, and reduced photosynthetic characteristics. However, high-nitrogen fertilizer treatment could efficiently alleviate and prevent the adverse effects of drought stress, enhance net photosynthetic rate and WUE, activate the activity of the reaction center OEC, enhance PS II performance and photosynthetic capacity, and reduce nonphotochemical quenching. In conclusion, the addition of 30-10-10 fertilizer to Hosta ‘Guacamole’ in summer could efficiently alleviate the adverse effects of drought stress and improve drought resistance. Our research provided an effective method for Hosta cultivation in drought season and a basis for future studies on the cultivation of Hosta spp. in view of climate change.

Materials and methods

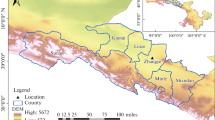

Plant materials and growth conditions

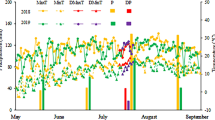

Hosta ‘Guacamole’ seedlings were planted in plastic pots (diameter 12 cm) containing substrate and perlite (V:V; 3:1) and grown in a greenhouse (30°56′ N, 121°28′ E, Shanghai, China) at 30/20°C (day/night) under natural light (maximum photosynthesis photon flux density of approximately 300 µmol m− 2 s− 1) with relative humidity of 70–85%. The details of the treatments are given in Table 2. In treatments T1, T2, and T3, varying watering frequency was applied for 50 days with 30 plants in each treatment. Subsequently, the 30 plants of T3 treatment were divided into 3 groups of 10 plants. Two groups (n = 10 each) received T5 and T6 treatments with N:P:K 30-10-10 and 15-10-30 fertilizers (ANOREL, Billy Fu Horticulture (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. ), respectively, and the remaining group (n = 10) received no fertilizer treatment (T4) for 30 days. The electric conductivity of fertilizers was 500 µs cm− 1, and the soil humidity in different treatment was different. The soil humidity was determined using hand-held soil tachymeter (Tianjin Tianhang Zhiyuan Technology Co., LTD, China) four times a week at fixed time (Fig. 10). Soil humidity was determined using 10 plots each time.

Measurements of area and chlorophyll content in the leaves of Hosta ‘Guacamole’

To determine the growth of leaves, a leaf area meter (Yaxin-1241, Beijing Yaxin Liyi Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) was used. Chlorophyll contents were determined using a portable chlorophyll meter SPAD-502 PLUS (Konica Minolta Optics, Tokyo, Japan) as per the method by Iqbal et al. [20]. To further analyze the effect of drought stress and water-soluble fertilizers on the leaf color, chroma meter (CR-400, KONICA MINOLTA, Japan) was used to measure the chromatic aberration values L*, a*, and b* that denote the brightness value, red-green degree value, and yellow-blue degree value, respectively. The leaf area, chlorophyll content, and chromatic aberration were measured using 15 plants in T1, T2, and T3 treatments. After applying the fertilizers at the 30th day, these parameters were measured using 10 plants each from T4, T5, and T6 treatments.

Assessment of photosynthetic parameters and chlorophyll fluorescence

The photosynthetic parameters, including Pn, gs, Tr, Ci, WUE, and VPD, were measured using CIRAS-3 portable photosynthesis system (PP Systems, Amesbury, MA, USA) with 260 µmol m− 2 s− 1 PPFD, 60–70% relative humidity, and ambient CO2 of 390 ppm. The measurements were performed using 9 plants from T1, T2, T3, T4, T5, and T6 treatments, respectively. Chlorophyll fluorescence of the leaves was measured using IMAGING-PAM (MAXI) (Zealquest Scientific Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). The leaves were placed in dark for 30 min prior to measurement. Maximum quantum yield of PS II (Fv/Fm), actual photochemical efficiency of PS II (ΦPS II), photochemical quenching coefficient (qP), non-photochemical quenching coefficient (NPQ), and electron transport rate (ETR) were measured. These measurements were performed thrice on four points on each side of the main vein from the tip to middle of the leaves.

Chlorophyll fluorescence rise kinetics and JIP-test parameters

Chlorophyll fluorescence rise kinetics were assessed using a Handy PEA continuous excitation fluorimeter (Handy Plant Efficiency Analyzer; Hansatech Instruments, Ltd., King’s Lynn, UK). The relative fluorescence parameters were calculated by double normalization of the moment chlorophyll fluorescence values to the end point within different intervals with the OJIP part of the transient-OP, OK, OJ, and OI. Following formulae were used for the calculations to clarify the structure and function of the photosynthetic apparatus by describing the primary photosynthetic reactions in PS II [29, 39]. The fluorescence parameters are listed in Table 3. Other formulae are given as follows: ΔWOK = WOK (treatment) − WOK (control); ΔWOJ = WOJ (treatment) − WOJ (control); ΔWL =WL(treatment) − WL(control); and ΔWK =WK(treatment) − WK(control). The JIP-test parameters including PI total, φEo, Fv/Fm, φRo, δRo, ψRo, and ψEo were measured with nine replications using Handy PEA continuous excitation fluorimeter for each treatment.

ROS scavenging

ROS including superoxide anion radical and H2O2 are scavenged by SOD and APX, respectively [36]. The SOD activity, APX activity, and GSH contents were measured as per the method by Yang et al. [37] using the kits by Wuhan ProNets Biotechnology Co, Ltd (Wuhan, China). The leaves of three individuals were mixed and considered as one replication. The experiment included three replicates. The details of extraction and determination of SOD activity, APX activity, and GSH contents are given in supplementary S1.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 19.0 (IBM, Inc., Armonk, NY, USA). The morphological and physiological parameters were analyzed using Duncan’s test (P < 0.05). The data were processed using Microsoft Excel 2007 (Redmond, CA, USA) and plotted using Origin Pro Version 8.5E (OriginLab, Northampton, MA, USA).

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- APX:

-

ascorbate peroxidase

- C i :

-

intercellular CO2 concentrations

- ETR:

-

electron transport rate

- Fv/Fm :

-

Maximum quantum yield of PS II

- g s :

-

stomatal conductance

- GSH:

-

Glutathione

- NPQ:

-

non-photochemical quenching coefficient

- P n :

-

net photosynthetic rate

- qP:

-

photochemical quenching coefficient

- SOD:

-

superoxide dismutase

- T r :

-

transpiration rate

- VPD:

-

vapor pressure deficit

- WUE:

-

water use efficiency

- ΦPS II:

-

actual photochemical efficiency of PS II

- φRo :

-

quantum yield of the electron transport flux until the PSI electron acceptors

- δRo :

-

efficiency with which an electron from QB is transferred until PSI acceptors

- ψRo :

-

electron transport efficiency except QA

- ψEo :

-

electron transport efficiency from QA− to the PSI electron end acceptors

References

Rahimi A, Mohammadi MM, Siavash Moghaddam S, Heydarzadeh S, Gitari H. Effects of stress modifier biostimulants on vegetative growth, nutrients and antioxidants contents of Garden Thyme (Thymus vulgaris L.) under Water Deficit conditions. J Plant Growth Regul. 2022;41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00344-022-10604-6.

Barra PJ, Inostroza NG, Mora ML, Crowley DE, Jorquera MA. Bacterial consortia inoculation mitigates the water shortage and salt stress in an avocado (Persea americana Mill.) Nursery. Appl Soil Ecol. 2017;111:39–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2016.11.012.

Seleiman MF, Al-Suhaibani N, Ali N, Akmal M, Alotaibi M, Refay Y, Dindaroglu T, Abdul-Wajid HH, Battaglia ML. Drought stress impacts on plants and different approaches to alleviate its adverse effects. Plants (Basel). 2021;10(2):259. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10020259.

Bouremani N, Cherif-Silini H, Silini A, Bouket AC, Luptakova L, Alenezi FN, Baranov O, Belbahri L. Plant growth-promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR): a Rampart against the adverse effects of Drought stress. Water. 2023;15(3):418. https://doi.org/10.3390/w15030418.

Dias MC, Azevedo C, Costa M, Pinto G, Santos C. Melia azedarach plants show tolerance properties to water shortage treatment: an ecophysiological study. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2014;75:123–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2013.12.014.

Zhang FJ, Zhang KK, Du CZ, Li J, Xing YX, Yang LT, Li YR. Effect of Drought stress on anatomical structure and Chloroplast Ultrastructure in leaves of Sugarcane. Sugar Tech. 2015;17:41–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12355-014-0337-y.

Qiu DR, Wang DC, Chung IM, Zhang MZ, Cheng H, Wei DS, Qin JC, Yang SX. Allelopathic effects of essential oil of Hosta ventricosa flowers on seed germination and seedling growth of crops. Allelopathy J. 2015;36:103–8.

Yang Z, Tian J, Feng K, Gong X, Liu J. Application of a hyperspectral imaging system to quantify leaf-scale chlorophyll, nitrogen and chlorophyll fluorescence parameters in grapevine. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2021;166:723–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2021.06.015.

Cui B, Zhao X, Chen G, Qin S, Liu Y, Han Z, Yan Q, Han L, Liu S, Liu S, Liu H. Functional analysis of two terpene synthase genes isolated from the flowers of Hosta ‘So Sweet’. Horticulturae. 2022;8(5):447. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae8050447.

Liu Q, Sun G, Wang S, Lin Q, Zhang J, Li X. Analysis of the variation in scent components of Hosta flowers by HS-SPME and GC–MS. Sci Hortic. 2014;175:57–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2014.06.001.

Miyazawa M, Utsumi Y, Kawata J. Comparison of the essential oils from wild type and cultivar type of Hosta sieboldiana. J Essent Oil Bear Pl. 2008;11:413–22.

Aelenei RI, Badea ML, Butcaru AC, Badulescu L, Toma F. Morphological and physiological particularities of Hosta leaves varieties cultivated in Romania. Sci Pap-Ser B-Hortic. 2020;64:287–92.

Yoo MJ, Lee BY, Kim S, Lim CE. Phylogenomics with Hyb-Seq unravels Korean Hosta Evolution. Front Plant Sci. 2021;12:645735. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.645735.

Toler JE, Adelberg JW, Bishop D. Growth and net photosynthetic rates of Hosta ‘blue vision’ during acclimatization in bright, natural light with CO2 enrichment. Vitro Cell Dev Biol. 2003;39:338–42. https://doi.org/10.1079/IVP2003414.

Zhang J, Shi L, Shi AP, Zhang QX. Photosynthetic responses of four Hosta cultivars to shade treatments. Photosynthetica. 2004;42:213–8. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:PHOT.0000040592.10133.

Zhuang QQ, Chen S, Jua ZX, Yao Y. Joint transcriptomic and metabolomic analysis reveals the mechanism of low-temperature tolerance in Hosta ventricosa. PLoS ONE. 2022;16(11). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0259455.

Sun B, Wang H, Huang Y, Yin Z, Zhou B. Characteristics and causes of the hot-dry climate anomalies in China during summer of 2022. Trans Atmospheric Sci. 2022; 1–9. (In Chinese).

Wang Y, An Y, Yu J, Zhou Z, He S, Ru M, Cui B, Zhang Y, Han R, Liang Z. Different responses of photosystem II and antioxidants to drought stress in two contrasting populations of Sour jujube from the Loess Plateau, China. Ecol Res. 2016;31:761–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11284-016-1384-5.

Abdel Wahab AM, Abd-Alla MH. The role of potassium fertilizer in nodulation and nitrogen fixation of faba bean (Vicia faba L.) plants under drought stress. Biol Fertil Soils. 1995;20:147–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00336594.

Iqbal N, Fatma M, Gautam H, et al. Salicylic acid increases photosynthesis of Drought grown mustard plants effectively with Sufficient-N via regulation of Ethylene, ABA and Nitrogen-Use Efficiency. J Plant Growth Regul. 2022;41:1966–77.

Mueller LM, Bahn M. Drought legacies and ecosystem responses to subsequent drought. Global Change Biol. 2022;28(17):5086–103.

Rabiei Z, Mohammadian Roshan N, Sadeghi SM, Amiri E, Doroudian HR. Effect of Drought stress and different levels of Nitrogen and Potassium fertilizers on the Accumulation of osmolytes and Chlorophyll in Rice (Oryza sativa L). Gesunde Flanz. 2021;73:287–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10343-021-00550-w.

Li Y, Han X, Ren H, Zhao B, Zhang J, Ren B, Gao H, Liu P. Exogenous SA or 6-BA maintains photosynthetic activity in maize leaves under high temperature stress. Crop J. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cj.2022.08.006.

Li T, Wang R, Zhao D, Tao J. Effects of drought stress on physiological responses and gene expression changes in herbaceous peony (Paeonia lactiflora Pall). Plant Signal Behav. 2020;15(5):1746034. https://doi.org/10.1080/15592324.2020.1746034.

Flexas J, Medrano H. Drought-inhibition of photosynthesis in C3 plants: stomatal and non-stomatal limitations revisited. Ann Bot. 2002;89(2):183–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcf027.

He L, Yu L, Li B, Du N, Guo S. The effect of exogenous calcium on cucumber fruit quality, photosynthesis, chlorophyll fluorescence, and fast chlorophyll fluorescence during the fruiting period under hypoxic stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2018;18:180. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-018-1393-3.

Guan X, Gu S. Photorespiration and photoprotection of grapevine (Vitis vinifera L. Cv. Cabernet Sauvignon) under water stress. Photosynthetica. 2009;47:437–44.

Ünlüsoy AG, Yolcu S, Bor M, Özdemir F, Türkan I. Activation of Photorespiration facilitates Drought stress tolerance in Lotus corniculatus. J Plant Growth Regul. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00344-022-10683-5.

Zhu J, Zhang YC, Yang Liuyan ZL. Effect of different LED lighting quality conditions on growth and Photosynthetic Characteristics of Saffron Plants (Crocus sativus L). Photosynthetica. 2022;60(4):510–20.

Strasser RJ, Tsimilli-Michael M, Srivastava A. Analysis of the Chlorophyll a fluorescence transient. – chlorophyll fluorescence: a signature of photosynthesis, advances in photosynthesis and respiration. 2004. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-3218-9_12.

Strasser RJ, Srivastava A, Tsimilli-Michael M. The fluorescence transient as a tool to characterize and screen photosynthetic samples. Probing Photosynthesis: Mechanism Regul Adaptation. 2000;25:445–83.

Khorobrykh S, Havurinne V, Mattila H, Tyystjärvi E. Oxygen and ROS in photosynthesis. Plants. 2020;9(1):91. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9010091.

Guo Y, Zhang Y, Lu Y, Shi J, Chen S, Strasser RJ, Qiang S, Hu Z. Effect of AtLFNR1 deficiency on chlorophyll a fluorescence rise kinetics OJIP of Arabidopsis. Photosynthetica. 2020;58:206–13.

Guo Y, Lu Y, Goltsev V, Strasser RJ, Kalaji HM, Wang H, Wang X, Chen S, Qiang S. Comparative effect of tenuazonic acid, diuron, bentazone, dibromothymoquinone and methyl viologen on the kinetics of Chl a fluorescence rise OJIP and the MR820 signal. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2020;156:39–48.

Gao Y, Liu W, Wang X, Yang L, Han S, Chen S, Strasser RJ, Valverde BE, Qiang S. Comparative phytotoxicity of usnic acid, salicylic acid, cinnamic acid and benzoic acid on photosynthetic apparatus of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2018;128:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2018.04.037.

D’Alessandro S, Beaugelin I, Havaux M. Tanned or sunburned: how excessive light triggers Plant Cell Death. Mol Plant. 2020;13(11):1545–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molp.2020.09.023.

Yang Z, Deng C, Wu Y, Dai Z, Tang Q, Cheng C, Xu Y, Hu R, Liu C, Chen X, Zhang X, Li A, Xiong X, Su J, Yan A. Insights into the mechanism of multi-walled carbon nanotubes phytotoxicity in Arabidopsis through transcriptome and m6A methylome analysis. Sci Total Environ. 2021;787:147510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147510.

Mittler R. Oxidative stress, antioxidants and stress tolerance. Trends Plant Sci. 2002;7(9):405–10.

Chen S, Zhou F, Yin C, Strasser RJ, Yang C, Qiang S. Application of fast chlorophyll a fluorescence kinetics to probe action target of 3-acetyl-5-isopropyltetramic acid. Environ Experimental Bot. 2011;71:269–79.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was jointly supported by Shanghai Plant Seedling Tissue Culture Professional Technical Service Platform (21DZ2292300).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jiao Zhu conceived and designed the study. Jiao Zhu and Xin Li performed the experiments and data analysis. Jiao Zhu wrote the paper with suggestions from Youming Cai, Liuyan Yang, and Yongchun Zhang. Jiao Zhu revised the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

We declare that the Hosta ‘Guacamole’ used in this study comply with relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines and legislation. The plant materials of Hosta ‘Guacamole’ were legally brought from Shanghai Yuanyi Seedlings Co. LTD, China. We confirm that all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, J., Cai, Y., Li, X. et al. High-nitrogen fertilizer alleviated adverse effects of drought stress on the growth and photosynthetic characteristics of Hosta ‘Guacamole’. BMC Plant Biol 24, 299 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-024-04929-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-024-04929-5