Abstract

Background

Sesame is a great reservoir of bioactive constituents and unique antioxidant components. It is widely used for its nutritional and medicinal value. The expanding demand for sesame seeds is putting pressure on sesame breeders to develop high-yielding varieties. A hybrid breeding strategy based on male sterility is one of the most effective ways to increase the crop yield. To date, little is known about the genes and mechanism underlying sesame male fertility. Therefore, studies are being conducted to identify and functionally characterize key candidate genes involved in sesame pollen development. Polyketide synthases (PKSs) are critical enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of sporopollenin, the primary component of pollen exine. Their in planta functions are being investigated for applications in crop breeding.

Results

In this study, we cloned the sesame POLYKETIDE SYNTHASE A (SiPKSA) and examined its function in male sterility. SiPKSA was specifically expressed in sesame flower buds, and its expression was significantly higher in sterile sesame anthers than in fertile anthers during the tetrad and microspore development stages. Furthermore, overexpression of SiPKSA in Arabidopsis caused male sterility in transgenic plants. Ultrastructural observation showed that the pollen grains of SiPKSA-overexpressing plants contained few cytoplasmic inclusions and exhibited an abnormal pollen wall structure, with a thicker exine layer compared to the wild type. In agreement with this, the expression of a set of sporopollenin biosynthesis-related genes and the contents of their fatty acids and phenolics were significantly altered in anthers of SiPKSA-overexpressing plants compared with wild type during anther development.

Conclusion

These findings highlighted that overexpression of SiPKSA in Arabidopsis might cause male sterility through defective pollen wall formation. Moreover, they suggested that SiPKSA modulates vibrant pollen development via sporopollenin biosynthesis, and a defect in its regulation may induce male sterility. Therefore, genetic manipulation of SiPKSA might promote hybrid breeding in sesame and other crop species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) is one of the most ancient oil crops and is widely used for its high-quality products. Its seeds are a great reservoir of oil, protein, unsaturated fatty acids, lignans, vitamins, and minerals [1, 2]. Moreover, many studies have revealed that sesame lignans possess various health-promoting abilities against lifestyle diseases [3,4,5,6]. Accordingly, the sesame seed market is expanding, placing great pressure on sesame breeders to develop environmentally stable and high-yielding varieties. A hybrid breeding strategy based on sterile male lines is one of the most reliable techniques to increase crop yield. Therefore, deciphering the molecular mechanism of fertility-related genes in sesame might provide genetic resources and new ideas for the crop improvement.

Pollen is a critical organ in angiosperm plant reproduction that facilitates pollination and fertilization [7]. Accordingly, its formation represents a key step of sexual reproduction in flowering plants. Male reproductive organ development is a complex biological process that consists of various biosynthesis events, among which pollen wall formation is essential for pollen viability and fertility [7, 8]. Any defects during pollen wall formation may lead to abnormal pollen and male sterility [9].

The pollen wall is an important structure of the outer surface of pollen. It comprises three layers: the pollen coat, the outer exine, and the inner intine [10]. The exine, a lipidic structure layer, is divided into two sublayers: an outer sculptured layer (the sexine) and a plain inner layer (the nexine). The sexine is constructed of rod-like structures called baculum, which are covered by a roof (of different shapes) called tectum [11]. Pollen exine patterning mainly includes three developmental events: primexine formation, callose wall formation, and sporopollenin synthesis [7, 10, 12]. Sporopollenin, a complex of fatty acids and phenolic compounds, represents the principal component that constitutes the pollen exine architecture [13].

Studies in Arabidopsis revealed that sporopollenin biosynthesis occurs in tapetal secretory cells after the temporary callose wall surrounding tetrads is degraded and primexine is deposited [14]. To date, several sporopolonin biosynthesis-related genes have been identified, such as ACYL-COA SYNTHETASE5 (ACOS5), Cytochrome P450 A2 (CYP703A2), Cytochrome P450 B1 (CYP704B1), MALE STERILITY2 (MS2), TETRAKETIDE a-PYRONE REDUCTASE1 (TKPR1), TETRAKETIDE a-PYRONE REDUCTASE 2 (TKPR2), POLYKETIDE SYNTHASEA (PKSA) and POLYKETIDE SYNTHASEB (PKSB) [15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. The sporopollenin biosynthesis pathway is conserved in land plant [7, 22,23,24,25]. Among the genes that contribute to vibrant and fertile pollen formation, polyketide synthases are critical [15, 16]. They catalyze the condensation of acyl-CoA molecules into hydroxyalkyl α-pyrone, the precursor of sporopollenin [7]. The Arabidopsis pksa/lap6 or pksb/lap5 mutant produces abnormal pollen exine, while the double mutant develops collapsed pollen without exine deposition and is male sterile [15, 16]. Kim et al. demonstrated that Arabidopsis POLYKETIDE SYNTHASE A/PKSA and PKSB (also known as LAP6 and LAP5, respectively) interact continuously with other pollen exine biosynthesis genes during anther development [15]. The integration of increasing genomic information and advanced genetic tools facilitates the transfer of information from Arabidopsis to other plants, including rice and rapeseed, in which orthologs of PKSA have been identified and characterized [26,27,28]. Manipulation of male fertility has been shown to be an effective method for hybrid breeding and increasing crop yields [29]. Therefore, genetic manipunation of PKSA gene might enhance hybrid breeding.

In sesame, although early studies reported strong heterosis [30, 31], few nuclear male sterile lines have been used in hybrid breeding [32, 33]. Studies on sesame male sterility were limited to the identification of two genes, Sesamum indicum male sterility 1 (SiMs1) [34] and Sesamum indicum cell wall invertase 1 (Sicwinv1) [35]. In the present study, sesame polyketide synthase A (SiPKSA) was cloned and functionally characterized to be involved in male reproduction. Our results suggest that SiPKSA might be involved in sporopollenin biosynthesis to affect pollen and pollen wall formation and it is a potential candidate gene for the improvement of sesame seed yield through hybrid breeding.

Results

Cloning and sequence analysis of SiPKSA

Sesame polyketide synthase, the ortholog of Arabidopsis PKSA, designated SiPKSA (Sesamum indicum Polyketide Synthase A), was cloned using the cDNA of sesame anthers at the tetrad stage as the template. The open reading frame (ORF) of SiPKSA is 1191 bp, encoding 396 amino acids, with an isoelectric point of 6.41, and a molecular weight of 43.6 kDa.

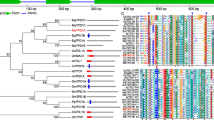

Multiple sequence alignment of the SiPKSA protein with other PKSA proteins reported in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), rice (Oryza sativa), and rape (Brassica napus) showed that the SiPKSA protein contains similar domains as polyketide synthase A in other species, including the typical chalcone/stilbene synthase N-terminal domain (25–242 bp), C-terminal domain (252–396 bp) and various conserved active sites, such as polypeptide binding site, malonyl-CoA binding site, and product binding site, as well as the catalytic triad Cys-His-Asn, which is common and important in the PKS family (Fig. 1A). The phylogenetic analysis of SiPKSA and polyketide synthases in other species indicated that SiPKSA is closer to PKSA in other species (Fig. 1B), confirming that SiPKSA encodes a polyketide synthase A protein.

Multiple sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis of SiPKSA with plant-specific type III polyketide synthases (PKSs) in other species. A Protein sequence alignment of SiPKSA with anther developmental-related PKSA from other crops. The conserved sites are underlined, and the amino acid residues are framed. AtPKSA (At1g02050), BnPKSA (XP_013701181.1), OsPKSA (NP_001064891.1). B Phylogenetic analysis of SiPKSA with PKSs from other species. Sesame indium (Si); Arabidopsis thaliana (At); Zea mays (Zm); Glycine max (Gm); Populus trichocarpa (Pt); Oryza sativa (Os); Brassica napus (Bn); Medicago truncatula (Mt); Citrus sinensis (Cs); Helianthus annuus (Ha); Arachis hypogaea (Ah); Brassica rapa (Br). The bootstrap values are shown at the nodes

In addition, the promoter region of SiPKSA was analyzed using the PLACE and PLANTCARE databases. We found that a large number of formal elements were annotated as MYB recognition sites, light-responsive elements, and auxin-responsive elements. Notably, multiple copies of AGAAA, which is considered as an anther- and/or pollen-specific cis-regulatory motif, are predicted in the promoter region of SiPKSA. Other motifs, such as Q-elements and GTGA motifs related to pollen development were also predicted in the promoter region (Table S2), indicating that SiPKSA might be involved in pollen development in sesame.

SiPKSA is predominantly expressed in sesame reproductive tissue

The expression pattern of SiPKSA in different organs of sesame was analyzed first to determine whether SiPKSA is tissue-specific. The results revealed that SiPKSA is predominantly expressed in flower buds (Fig. 2A and B), indicating that its function in sesame might be related to plant reproduction. Furthermore, to determine the potential role of SiPKSA in sesame male sterility, we compared the expression pattern of SiPKSA in sterile and fertile sesame anthers at different developmental stages. We observed that the expression of SiPKSA was significantly higher in sterile sesame anthers at the tetrad stage and microspore development stage than in fertile anthers (Fig. 2C and D), suggesting that high expression of SiPKSA might induce male sterility in sesame. Thus, normal activity and levels of SiPKSA might be required for sesame male fertility.

Expression analysis of SiPKSA in sesame. A-B The expression profile of SiPKSA in different sesame tissues by RT-PCR (A) and qRT-PCR analysis (B). C-D RT-PCR (C) and qRT-PCR analysis (D) of the expression of SiPKSA in sesame fertile and sterile anthers at different developmental stages. S-t, S-md, and S-mp represent the tetrad stage, microspore development stage, and mature pollen stage of the sterile anthers, respectively. F-t, F-md, and F-mp represent the tetrad stage, microspore development stage, and mature pollen stage of the fertile anthers, respectively. Si-Actin (SIN_1009011) was used as the internal reference control. Three biological replicates were conducted and the error bars represent ± SD. Statistically significant differences were assessed using Student’s t-test (**p < 0.01 is considred a highly significantly different)

Overexpressing SiPKSA in Arabidopsis caused male sterility in transgenic plants

To further assess the in planta function of SiPKSA and investigate the effects of its high expression during anther development, we engineered Arabidopsis plants to overexpress the SiPKSA gene under the 35 s promoter. Several transgenic lines were harvested, among which we selected two independent homozygous lines in the T3 generation for phenotypic and functional analyses. The expression of SiPKSA was highly induced in the two independent homozygous lines compared to the wild type plants (WT) and the plants transformed with empty vector (EV) (Fig. 3A). The expression level of the Arabidopsis homologous gene AtPKSA was also detected. The results showed that there were no significant differences between SiPKSA-overexpressing plants, wild-type plants, or plants transformed with empty vector in terms of the expression level of AtPKSA both in seedlings and anthers at different developmental stages (Fig. S1A-C), suggesting that the phenotype of transgenic plants in the present study was caused by SiPKSA.

Ectopic expression of SiPKSA in Arabidopsis caused male sterility of transgenic plants. A RT-PCR analysis of SiPKSA in SiPKSA-overexpressing lines (OX-1, OX-3), wild-type (WT) and plants transformed with empty vector (EV). At-Actin7 (At5g09810) was used as an internal standard. B The phenotype of 8-week-old SiPKSA-overexpressing Arabidopsis plants. The scale bar represents 2 cm. C Comparison of the length of the siliques of SiPKSA-overexpressing Arabidopsis plants (below), WT (middle), and EV (above) (D-E) Magnified image of SiPKSA-overexpressing plant (D), WT plant (E), and EV (F). The white arrow indicated the siliques of the plants. The scale bars represent 1 cm. (G-I) Detection of pollen vigor of WT (G), SiPKSA-overexpressing plants (H) and EVs (I) with 0.5% acetocarmine reagent. The red arrow shows the stained pollen. The pollen grains of WT and EV were dyed red, while the pollen grains of SiPKSA-overexpressing plant were not colored. J, K The phenotype of pollen grains of WT under SEM. L, M. The phenotype of pollen grains of SiPKSA-overexpressing plants under SEM. Scale bars represent 100 μm (G-I), 10 μm (J, L) and 2 μm (K, M)

As shown in Fig. 3B, no significant phenotypic difference was observed between the wild-type (WT) plants, the plants transformed with empty vector (EV), and the SiPKSA-overexpressing plants, except for the silique size. The siliques of SiPKSA-overexpressing plants were flat and short compared to those of the wild type (WT) and the plants transformed with the empty vector (EV) (Fig. 3C-E).

To enhance the contrast of the pollen grains under the microscope, acetocarmine solution also known as a nuclear and chromosomal fixation and staining agent, was used for staining to investigate the pollen phenotype. Microscopic observations showed that the pollen grains of WT and EV were plump and darkly stained (Fig. 3F and H), indicating high pollen viability. In contrast, the pollen grains of SiPKSA-overexpressing plants were uncolored and small, indicating poor vigor (Fig. 3G).

To verify the above observations, we scanned the pollen using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The results confirmed that the WT pollen grains were normal and those of the SiPKSA-overexpressing plants were abnormal. The WT pollen grains were full with a typical sculptured surface (Fig. 3I and J), while those of the SiPKSA-overexpressing plants were shrunken and collapsed (Fig. 3K and L). These results indicated that SiPKSA-overexpressing plants were male sterile.

Abnormal pollen and pollen wall development in SiPKSA-overexpressing Arabidopsis plants

According to the cytological events, Arabidopsis anther development is characterized into 14 stages, and the microspores differentiate into mature pollen during stages 9–12 [8]. We then conducted transmission electron microscopy (TEM) observations to further investigate the ultrastructure of the pollen and pollen walls during anther development. Our results showed that during stages 9–10, the tapetum of WT contained small vacuoles and abundant plastids filled with plastoglobuli (plastid lipoprotein particles), which can synthesize and store the carbohydrates and lipids needed for microspore development (Fig. 4A). The microspores of WT were rich in inclusions and embedded within the regular primary structure of the exine (Fig. 4B). However, in the tapetal cells of SiPKSA-overexpressing plants, large cavities and fewer cytoplasmic inclusions were observed (Fig. 4C). The microspores of SiPKSA-overexpressing plants were obviously abnormal with few cytoplasmic components, and compared with the WT, the sporopollenin particles on the pollen exine of the SiPKSA-overexpressing plants were abundant, disorderly and sparsely deposited on the microspore surface (Fig. 4D) During stages 11–12, the pollen of WT exhibited a typical normal pollen wall with obvious exine and intine layers (Fig. 4E). In contrast, the pollen grains of SiPKSA-overexpressing plants were seriously collapsed, with irregular exines and intines (Fig. 4F). Regarding the thickness of the pollen exine during stages 9–10 and 11–12, the results showed that the exine layer of SiPKSA-overexpressing plants was significantly thicker than that of the WT (Fig. 5A-E).

Transmission electron micrographs (TEM) observation of the ultrastructure of microspores and tapetum development of wild-type and SiPKSA-overexpressing plants at different anther developmental stages. A, C Tapetal cells of the WT (A) and SiPKSA-overexpressing plants during stages 9–10 (C). B, D Microspores of the WT (B) and SiPKSA-overexpressing plants during stages 9–10 (D). (E, F) Pollen walls of WT (E) and SiPKSA-overexpressing plants (F) at stages 11–12. Msp, microspore; DMsp, degenerated microspore; T, tapetum; In, intine; Ex, exine; N, nucleus; P, plastid filled with plastoglobuli; PG, pollen grain. Scale bars are 2 μm

TEM observation of pollen walls from wild-type (WT) and SiPKSA-overexpressing plants at different anther developmental stages. A-D The ultrastructure of the pollen wall of WT and SiPKSA-overexpressing plants at anther developmental stages 9–10 and 11–12. E The thickness of the exine layer at stages 9–10 and 11–12. Ex, exine; In, intine. The scale bars are 1 μm. Three biological replicates were conducted, and the error bars indicate ± SD. The measurements were repeated ten times for each sample. Statistically significant differences were assessed using Student’s t-test (*p < 0.05 is considred a significantly different, **p < 0.01 is considred a highly significantly different)

Overexpression of SiPKSA altered the expression of sporopollenin biosynthesis-related genes and fatty acid metabolism

The main component of pollen exine is sporopollenin, therefore, the expression of several sporopollenin biosynthesis-related genes, including AtMS2, AtCYP704B1, AtTKPR1, and AtTKPR2 was analyzed by qRT-PCR. Comparing to WT, the expression of AtMS2 was up-regulated in anthers of SiPKSA-overexpressing plants during stages 6–8, and significantly down-regulated during stages 9–10 and 11–12. The expression of AtCYP704B1 was significantly elevated in anthers of SiPKSA-overexpressing plants during stages 6–8, and dramatically reduced during stages 9–10, and significantly elevated during stages 11–12. The expression of AtTKPR1 and AtTKPR2 was remarkably down-regulated in anthers of SiPKSA-overexpressing plants during stages 6–8, 9–10, and 11–12 (Fig. 6 and Table S3). These results indicated that the expression of sporopollenin biosynthesis-related genes is influenced by the high expression of SiPKSA in transgenic Arabidopsis.

qRT-PCR analysis of the pollen development-related genes in the controls and SiPKSA-overexpressing plants. The expression of the pollen development-related genes are altered in anthers of SiPKSA-overexpressing plants compared with WT during anther development. Three biological replicates were performed, and the error bars represent ± SD. The expression was normalized to AtActin7 (At5g09810). Statistically significant differences were assessed using Student’s t-test (*p < 0.05 is considred a significantly different, **p < 0.01 is considred a highly significantly different). AtMS2 (At3g11980), AtCYP704B1 (At1g69500), AtTKPR1 (At4g35420), and AtTKPR2 (At1g62940)

The fatty acids composition of the anthers at different developmental stages was further investigated by GC–MS analysis. The results showed that, in comparison with the WT, the content of several long-chain fatty acids was greatly affected in anthers of SiPKSA-overexpressing plants during the anther development. During stages 6–8, the contents of C15:1, C16:0, ethyl-C16, C16:1ω11, C22:1, and C22:2 were significantly increased, while the contents of C16:3, C18:1, and C18:1 T were significantly decreased. During stage 13, the content of most long-chain fatty acids decreased, while the content of C16:1ω11 and C18:1 increased (Fig. 7A). In addition, the content of three phenolic compoundswas significantly influenced. The C15-OH and C25-2OH contents significantly increased, while the C14-OH content decreased during stages 6–8 in SiPKSA-overexpressing plants (Fig. 7B). The fatty alcohol (Phytol) content greatly increased at both stages 6–8 and stage 13 in SiPKSA-overexpressing plants (Fig. 7B). These results indicated that normal fatty acid metabolism was affected in anthers of SiPKSA-overexpressing plants, consistent with the abnormal pollen and pollen wall development in the SiPKSA-overexpressing plants.

Measurement of fatty acids and their derivatives in anthers of SiPKSA-overexpressing plants and wild-type plants by GC–MS. A The content of fatty acids in anthers at stages 6–8 and 13. B The contents of phenols and fatty alcohols in anthers at stages 6–8 and 13. C12:0, Lauric acid methyl ester; C14:0, Methyl tetradecanoate; C15:0, Pentadecanoic acid methyl ester; C15:1, 9-Octadecenoic acid methyl ester; C16:0, Hexadecanoic acid methyl ester; ethyl-C16:0, 9-Hexadecenoic acid methyl ester; C16:1ω11, 11-Hexadecenoic acid methyl ester; C16:2, 7,10-Hexadecadienoic acid methyl ester; C16:3, 7,10,13-Hexadecatrienoic acid methyl ester; hexade-C16, Hexadecanedioic acid dimethyl ester; butyl-C16, butyl isobutyl phthalate; C17:0, Heptadecanoic acid methyl ester; C18:0, Methyl stearate; iso-C18:0, Methyl isostearate; C18:1, (Z)-9-Octadecenoic acid methyl ester; C18:1 T, 9,12,15-Octadecatrienoic acid ethyl ester; C20:0, Arachidic acid methyl ester; C20:1, cis-11-Eicosenoic acid methyl ester; C20:2, 11,13-Eicosadienoic acid methyl ester; C22:1, 13-Docosenoic acid methyl ester; C22:2, cis-13,16-Docasadienoic acid methyl ester; C24:0, Tetracosanoic acid methyl ester; Phenol(C15-OH), Butylated Hydroxytoluene; Phenol(C14-OH), 2,4-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-Phenol; Phenol(C25-2OH), 2,2′-methylenebis[6-(1,1-dimethylethyl)]-4-methyl-Phenol. Three biological replicates were performed and the error bars represent ± SD. Statistically significant differences were assessed using Student’s t-test (**p < 0.01 is considred a highly significantly different)

Discussion

SiPKSA is a typical chalcone synthase with a similar function as its homologs

Polyketide compounds are usually produced under the action of polyketide synthases (PKSs). PKSs can be divided into three types (I, II, and III) according to their protein structure [36, 37]. Type III PKSs, also known as the chalcone synthase (CHS) superfamily, are responsible for the biosynthesis of monocyclic or bicyclic aromatic polyketide compounds [38]. A series of type III PKSs with different functions have been characterized in plants, such as chalcone synthase (CHS), stilbene synthase (STS), acribone synthase (ACS), and 2-pyrone synthase (2-PS). These type III PKSs harbor a highly conserved catalytic active center (Cys164-His303-Asn336), and their active amino acid residues, generally Thr197, Phe215, Gly256, and Ser338, are located in the cavity of the active center [39]. However, the active site and amino acid residues of different functions of type III PKSs are slightly different to enable the production of diverse products [40].

In this study, multiple sequence alignment results showed that the SiPKSA protein possesses a typical chalcone synthase structure and conserved active catalytic centers with active amino acid residues as per the AtPKSA, BnPKSA, and OsPKSA/OsPKS1 proteins (Fig. 1A). Additionally, the phylogenetic analysis grouped the SiPKSA protein and PKSAs from other species (Fig. 1B). These findings indicate that SiPKSA is a type III PKSs and is homologous to other PKSAs. It has been reported that plant-specific CHS-like type III PKSs LAP6/PKSA and LAP5/PKSB are specifically expressed in anthers and are critical for proper pollen development [16]. OsPKS1, a homolog of LAP6/PKSA, also has a similar function [23].

In agreement with this finding, SiPKSA was expressed specifically in sesame flower buds (Fig. 2A-B). Overexpression of SiPKSA in Arabidopsis caused male sterility in transgenic plants. The pollen grains of SiPKSA-overexpressing plants were collapsed and embedded within a defective pollen wall (Fig. 4). These results suggest that SiPKSA plays a similar function as its homologs and is specifically involved in plant reproduction.

SiPKSA is required for proper pollen exine formation and might be involved in sporopollenin biosynthesis

In Arabidopsis, the pksa mutant showed an incompletely male-sterile phenotype, with a thinner pollen exineand a shorter baculum and tectum compared to the wild-type plant [15]. In rice, the OsPKS1 knockout mutant obtained by CRISPR-Cas9-mediated genome editing exhibited a complete male-sterile phenotype. Cytological observations revealed that the baculum of the rice Ospks1 mutants was shorter, granular, and collapsed, with abnormal deposits [23]. A single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) mutation of the OsPKS1 gene also showed the same phenotype of male sterility caused by defective pollen walls [24]. In addition, it has been reported that mutants of other sporopollenin biosynthesis-related genes, including CYP704B1, MS2, TKPR1, and TKPR2, exhibit defective or absent pollen exine [15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. These reports all showed that downregulation of these genes causes decreased sporopollenin biosynthesis, leading to lack of or much thinner pollen exine layers. However, the male sterility of the cotton Line 1335A is associated with upregulation of the expression level of sporopollenin biosynthesis-related genes which results in excessive sporopollenin accumulation, leading to thicker nexine (the inner layer of the exine) formation [41].

These studies indicated that normal sporopollenin biosynthesis might be required for proper pollen exine formation. In agreement with this point, in our study, overexpression of SiPKSA induced male sterility in transgenic Arabidopsis. The pollen walls of SiPKSA-overexpressing plants were defective. The baculum of the pollen exine was loosely and disorderly arranged compared to the wild-type plants. The thickness of the exine increased significantly, suggesting an increase in sporopollenin biosynthesis that led to its excessive accumulation in transgenic Arabidopsis plants (Figs. 4 and 5). qRT-PCR analysis revealed that the expression of several sporopollenin biosynthesis-related genes was significantlyinfluenced by the overexpression of SiPKSA during anther development, suggesting there might be a feedback regulation (Fig. 6).

Many studies have demonstrated that sporopollenin is a complex biopolymer comprised mainly of fatty acids and phenolic and aliphatic compounds [7, 14]. With the identification of some genes related to sporopollenin synthesis, an increasing number of biochemical experiments in vitro have been conducted to explore their biochemical function. Studies have shown that both AtPKSA and the closely related AtPKSB can catalyze the condensation of long-chain fatty acids acyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA to produce α-pyrone products. Accordingly, AtPKSA is known as a multifunctional enzyme and is vital for the synthesis of both pollen exine fatty acids and phenolics [15, 16]. Rice OsLAP6/OsPKS1 shares similar products of enzymatic reactions with AtPKSA/LAP6 [27]. Similarly, PpASCL, a homolog of AtPKSA/LAP6 in moss, encodes a sporophyte-specific enzyme that possess similar catalytic activity as AtPKSA/LAP6 in vitro [26].

In this study, we found that overexpression of SiPKSA in transgenic Arabidopsis affected the contents of various long-chain fatty acids compared to wild-type plants. Moreover, the contents of several phenolic compounds were increased in the SiPKSA-overexpressing lines (Fig. 7), suggesting that the overexpression of SiPKSA altered fatty acid metabolism in anthers. Although previous chemical analysis suggested that the primary components of sporopollenin precursors are polyhydroxy long-chain or very long-chain fatty acids, in addition to oxidized aromatic derivatives, the natural chemical monomer composition of sporopollenin remains poorly defined due to technical limitations [22, 23]. In addition, the homeostasis of fatty acid metabolism is critical for pollen and pollen wall development [42]. These reports support the observed changes in the content of several long-chain fatty acids during anther development in our study. In addition, our results indicate a great perturbation of the homeostasis of fatty acid metabolism in developing anthers of SiPKSA-overexpressing plants compared to wild type plant.

Normal expression of PKSA might be required for fertile pollen formation

Previous studies have shown that pksa mutants in both Arabiodopsis and rice cause defective pollen exine and induce male sterility [15,16,17]. In addition, in tobacco, interference with the expression of NtPKSA also caused disorganized pollen surface sculptures [27]. These studies indicated that mutation in the PKSA gene might lead to abnormal pollen formation. Herein, we found that SiPKSA was highly expressed in sterile sesame during the tetrad release and microspore development stages compared with fertile sesame (Fig. 2C-D). Overexpression of SiPKSA induced male sterility in transgenic Arabidopsis (Fig. 3). The pollen walls of SiPKSA-overexpressing plants were defective. The baculum of the pollen exine was loosely and disorderly arranged compared to the wild-type plants (Fig. 4). The thickness of the exine increased significantly (Fig. 5), suggesting an increase in sporopollenin biosynthesis that led to its excessive accumulation in transgenic Arabidopsis plants. Therefore, we deduced that normal expression and activity of PKSA might be essential for proper pollen development. Any defect in its expression may lead to abnormal pollen formation via imperfect exine development. Additional investigations are required to explore the intricate regulatory mechanisms of PKSAs in general.

Conclusion

In this study, we cloned and characterized sesame polyketide synthase A (SiPKSA). Sequence analysis and tissue expression pattern analysis showed that SiPKSA is a polyketide synthase closely related to the development of sesame anthers. We found that high expression of SiPKSA is associated with male sterility through abnormal pollen and pollen wall development. Overexpression of SiPKSA in transgenic Arabidopsis confirmed that normal activity of PKSAs is required for vibrant pollen formation. The overexpression of SiPKSA altered fatty acid metabolism and significantly influenced the expression of sporopollenin biosynthesis-related genes in transgenic Arabidopsis. Thus, SiPKSA is a potential candidate gene for the genetic improvement of sesame seed yield through hybrid breeding. An in-depth examination of the molecular mechanisms involved in SiPKSA regulation during anther development is required to adequately exploit this valuable genetic resource.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

The sesame male-sterile mutant 95 ms-5A and its fertile segregant 95 ms-5B [34] were cultivated under natural conditions at the experimental station of the Oil Crops Research Institute of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (OCRI-CASS, Wuhan, China). Arabidopsis ecotype Colombia (Col-0) was grown under standard growth conditions, the temperature was maintained at approximately 22 °C, the light intensity was 130 μE/m2s, and the photoperiod was 16 h light/8 h dark. All of the plant materials were provided by the OCRI-CASS. Study complied with local and national regulations for using plants.

Cloning and sequence analysis

The ORF of SiPKSA was amplified with the specific gene primers SiPKSA-f (5′-ATGTCCAACATCATCATCAACAGC-3′) and SiPKSA-r (5′-TCAAAGACTCCTAAGAAGAATGCCT-3′) via PCR using fertile sesame anthers in the tetrad stage as the template. The physical and chemical properties of SiPKSA were analyzed using the EXPASY database (https://web.expasy.org/protparam/). The PLANTCARE and PLACE databases were used to analyze the cis-acting elements of SiPKSA [43, 44].

For multiple sequence alignment analysis, SiPKSA and three other PKSAs (AtPKSA, At1g02050; OsPKSA, NP_001064891; BnPKSA, XP_013701181) were aligned by the ClustalX program. For phylogenetic analysis, SiPKSA and selected PKSs from other species (Arabidopsis thaliana, At4g34850; Brassica napus, XP_013707052; Helianthus annuus, XP_022010182; Glycine max, XP_003537759, XP_003516799; Populus trichocarpa, XP_002302511; Oryza sativa, XP_015646301; Zea mays, PWZ54429; Arachis hypogaea, XP_015971059, XP_015952719; Mesicago truncatula, XP_024638419; Brassica rapa, XP_009108697) were subsequently used to construct a phylogenetic tree via MEGA-X with the neighbor-joining method as the default and 1000 bootstrap replicates [45]. All sequences were downloaded from the NCBI database.

Vector construction and plant transformation

First, the ORF of SiPKSA was inserted into TSV-007S vector (Tsingke, China) and sequenced. Subsequently, through double enzyme digestion (restriction site: NdeI and SmaI), the fragment was ligated into PRI101-AN (Takara, Japan) to generate the overexpression vector (35S::SiPKSA) according to previously described methods [46, 47]. The expression vector was then introduced into Arabidopsis thaliana (Col-0) through Agrobacterium tumefaciens (strain GV3101) using the floral dip method [48]. Positive transgenic lines were screened on 1/2 MS solid medium containing 50 μg/mL kanamycin. Arabidopsis plants transformed with empty vector (EV) and wild-type Arabidopsis (WT) were used as the control.

Plant morphology and pollen viability analysis

When the seedlings were eight weeks old, the phenotypes of the transgenic plants were photographed using a Nikon D90 digital camera. Pollen grains from wild-type Arabidopsis, wild-type Arabidopsis transformed with empty vector, and SiPKSA-overexpressing plants were placed on a glass slide, and 0.5% acetyl carmine reagent which was dropped on them and mixed thouroughly. After covering the slide for 30 min, the excess liquid was removed and observed under a microscope. Photographs were captured using an optical microscope (IX71, Olympus). All plump and darkly stained pollen grains were determined to be fertile, and the collapsed and unstained pollen grains were considered sterile.

Ultrastructure observation

For the scanning electron microscopy (SEM) observation, anthers sampled from freshly dehisced anthers of WT, EV, and SiPKSA-overexpressing plants were dehydrated in 30, 50, 70, 80, 90, 95 and 100% ethanol series. The dehydrated samples were dried to the critical point in liquid CO2 and coated with gold particles. The images were acquired by a scanning electron microscope (VEGA3, Tescan).

For transmission electron microscopy (TEM) observation, anthers at different developmental stages collected from WT and SiPKSA-overexpressing plants were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde at 4 °C overnight. Next, the samples were postfixed with 1% osmium tetroxide and subsequently dehydrated twice in 30, 50, 70, 80, 90, 95, and 100% ethanol for 15–20 min each time. After that, the samples were infiltrated with a mixture of acetone and epoxy resin in different proportions. The dehydrated samples were then embedded in epoxy resin and polymerized at 60 °C (incubator) for 48 h. Furthermore, they were sliced at a thickness of 80–100 nm by an ultrathin slicer (EMUC7, Leica) and stained with uranium-lead double staining solution. Images were captured using a transmission electron microscope (TecnaiG220 TWIN). The thickness of the exine was measured using Nano measurer 1.2 software (http://emuch.net/html/201402/7022970.html). Three biological replicates were performed, and three microspores were measured for each replicate. The measurements were repeated ten times for each sample, following the method of Wu et al. [41].

RNA isolation, RT-PCR and qRT-PCR analysis

Sesame roots, stems, leaves, flower buds, and capsules were collected for expression profile analysis of SiPKSA in sesame. To compare the expression difference of SiPKSA between sterile sesame plants (95 ms-5A) and the fertile plants (95 ms-5B), anthers at different developmental stages (tetrad stage, microspore development stage, and mature pollen stage) from sterile sesame plants (95 ms-5A) and the fertile plants (95 ms-5B) were sampled. Expression was normalized to SiActin (SIN_1009011) [49]. For expression analysis of sporopollenin biosynthesis-related genes in Arabidopsis anthers at different developmental stages (stages 6–8, 9–10, 11–12) from the wild type and SiPKSA-overexpressing plants were sampled. Expression was normalized to AtActin7 (At5g09810) [50]. Total RNA was extracted from each sample using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, USA). First-strand cDNA was synthesized by SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Vazyme Biotech, Nanjing, China). qRT-PCR was carried out using the Roche Light Cycler 480 system. The relative expression level was calculated using the 2−△△Ct method [51]. The primers used in this study were listed in Table S1.

Fatty acids and their derivates measurements

Anthers (0.2 g) at different developmental stages sampled from WT and the SiPKSA-overexpressing plants were extracted twice with 1 mL of chloroform for 2 h. Next, the mixed supernatant was re-extracted and dried with a nitrogen blower. Finally, 0.25 mL of 5% potassium hydroxide-methanol solution was added, and the mixture was incubated at 60 °C for 30 min and subsequently quenched with n-hexane. The final supernatant was analyzed by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). The chromatographic conditions of GC-MS were as follows: inlet temperature 280 °C, split ratio 20:1, carrier gas: He, carrier gas flow rate: 1.0 ml/min, ion source temperature 230 °C, scanning mass range 35 ~ 800 M. The injection volume was 1 μL. The temperature rising program: The initial temperature was 50 °C and kept for 1 min; the temperature was increased to 200 °C gradually (5 °C/min); finally, the temperature wasincreased to 230 °C and held for 10 min.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed with three biological replicates, and the presented values are the mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined using Student’s t-test (*P < 0.05 is considred significantly different, **P < 0.01 is considred highly significantly different).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- ORF:

-

Open Reading Frame

- WT:

-

Wild Type

- EV:

-

Transformed Plants with Empty Vector

- OX:

-

Overexpression Lines

- RT-PCR:

-

Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction

- qRT-PCR:

-

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

- SEM:

-

Scanning Electron Microscope

- TEM:

-

Transmission Electron Microscope

References

Orruno E, Morgan MRA. Purification and characterisation of the 7S globulin storage protein from sesame (Sesamum indicum L.). Food Chem. 2007;100(3):926–34.

Anilakumar KR, Pal A, Khanum F, Bawa AS. Nutritional, medicinal and industrial uses of sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) seeds - an overview. Agriculturae Conspectus Scientificus (Poljoprivredna Znanstvena Smotra). 2010;75(4):159–68.

Majdalawieh AF, Dalibalta S, Yousef SM. Effects of sesamin on fatty acid and cholesterol metabolism, macrophage cholesterol homeostasis and serum lipid profile: A comprehensive review. Eur J Pharmacol. 2020;885:173417.

Majdalawieh AF, Mansour ZR. Sesamol, a major lignan in sesame seeds (Sesamum indicum): Anti-cancer properties and mechanisms of action. Eur J Pharmacol. 2019;855:75–89.

Majdalawieh AF, Massri M, Nasrallah GK. A comprehensive review on the anti-cancer properties and mechanisms of action of sesamin, a lignan in sesame seeds (Sesamum indicum). Eur J Pharmacol. 2017;815:512–21.

Wu M-S, Aquino LBB, Barbaza MYU, Hsieh C-L, De Castro-Cruz KA, Yang L-L, et al. Anti-inflammatory and anticancer properties of bioactive compounds from Sesamum indicum L.-A Review. Molecules. 2019;24(24):4424.

Ariizumi T, Toriyama K. Genetic regulation of sporopollenin synthesis and pollen exine development. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2011;62(1):437–60.

Sanders BAQ, Weterings K, et al. Anther developmental defects in Arabidopsis thaliana. Sex Plant Reprod. 1999;11(6):297–322.

Gomez JF, Talle B, Wilson ZA. Anther and pollen development: A conserved developmental pathway. J Integr Plant Biol. 2015;57(11):876–91.

Xu DW, Shi JX, Rautengarten C, Yang L, Qian XL, Uzair M, et al. Defective Pollen Wall 2 (DPW2) encodes an acyl transferase required for rice pollen development. Plant Physiol. 2017;173:240–55.

Dong XY, Hong ZL, Sivaramakrishnan M, Mahfouz M, Verma DPS. Callose synthase (CalS5) is required for exine formation during microgametogenesis and for pollen viability in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2005;42:315–28.

Blackmore S, Wortley AH, Skvarla JJ, Rowley JR. Pollen wall development in flowering plants. New Phytol. 2007;174(3):483–98.

Liu L, Fan X-D. Tapetum: regulation and role in sporopollenin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol Biol. 2013;83(3):165–75.

Shi J, Cui M, Yang L, Kim Y-J, Zhang D. Genetic and biochemical mechanisms of pollen wall development. Trends Plant Sci. 2015;20(11):741–53.

Kim SS, Grienenberger E, Lallemand B, Colpitts CC, Kim SY, Souza CA, et al. LAP6/POLYKETIDE SYNTHASE A and LAP5/POLYKETIDE SYNTHASE B Encode Hydroxyalkyl α-Pyrone Synthases Required for Pollen Development and Sporopollenin Biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell. 2010;22(12):4045–66.

Dobritsa AA, Lei Z, Nishikawa S-I, Urbanczyk-Wochniak E, Huhman DV, Preuss D, et al. LAP5 and LAP6 encode anther-specific proteins with similarity to chalcone synthase essential for pollen exine development in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2010;153(3):937–55.

Dobritsa AA, Geanconteri A, Shrestha J, Carlson A, Kooyers N, Coerper D, et al. A Large-scale genetic screen in Arabidopsis to identify genes involved in pollen exine production. Plant Physiol. 2011;157(2):947–70.

Dobritsa AA, Shrestha J, Morant M, Pinot F, Matsuno M, Swanson R, et al. CYP704B1 is a long-chain fatty acid ω-Hydroxylase essential for sporopollenin synthesis in pollen of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2009;151(2):574–89.

Grienenberger E, Kim SS, Lallemand B, Geoffroy P, Heintz D, Souza CA, et al. Analysis of TETRAKETIDE α-PYRONE REDUCTASE function in Arabidopsis thaliana reveals a previously unknown, but conserved, biochemical pathway in sporopollenin monomer biosynthesis. Plant Cell. 2010;22(12):4067–83.

de Azevedo SC, Kim SS, Koch S, Kienow L, Schneider K, McKim SM, et al. A novel fatty acyl-COA synthetase is required for pollen development and sporopollenin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2009;21(2):507–25.

Lallemand B, Erhardt M, Heitz T, Legrand M. Sporopollenin biosynthetic enzymes interact and constitute a metabolon localized to the endoplasmic reticulum of tapetum cells. Plant Physiol. 2013;162(2):616–25.

Quilichini TD, Grienenberger E, Douglas CJ. The biosynthesis, composition and assembly of the outer pollen wall: A tough case to crack. Phytochemistry. 2015;113:170–82.

Shi Q-S, Wang K-Q, Li Y-L, Zhou L, Xiong S-X, Han Y, et al. OsPKS1 is required for sexine layer formation, which shows functional conservation between rice and Arabidopsis. Plant Sci. 2018;277:145–54.

Zou T, Xiao Q, Li W, Luo T, Yuan G, He Z, et al. OsLAP6/OsPKS1, an orthologue of Arabidopsis PKSA/LAP6, is critical for proper pollen exine formation. Rice. 2017;10(1):53.

Zhang D, Shi J, Yang X. Role of Lipid Metabolism in Plant Pollen Exine Development. In: Nakamura Y, Li-Beisson Y, editors. Lipids in Plant and Algae Development. Subcellular Biochemistry, 2016, vol 86.

Colpitts CC, Kim SS, Posehn SE, Jepson C, Kim SY, Wiedemann G, et al. PpASCL, a moss ortholog of anther-specific chalcone synthase-like enzymes, is a hydroxyalkylpyrone synthase involved in an evolutionarily conserved sporopollenin biosynthesis pathway. New Phytol. 2011;192(4):855–68.

Wang Y, Lin Y-C, So J, Du Y, Lo C. Conserved metabolic steps for sporopollenin precursor formation in tobacco and rice. Physiol Plant. 2013;149(1):13–24.

Qin M, Tian T, Xia S, Wang Z, Song L, Yi B, et al. Heterodimer formation of BnPKSA or BnPKSB with BnACOS5 constitutes a multienzyme complex in tapetal cells and is involved in male reproductive development in Brassica napus. Plant Cell Physiol. 2016;57(8):1643–56.

Guo JX, Liu YG. Molecular control of male reproductive development and pollen fertility in rice. J Integr Plant Biol. 2012;54:967–78.

Ding FY, Jiang JP, Zhang DX, Li GS. A study on relationship between heterosis and effects of combining ability in sesame. Acta Agriculturae Boreali-Sinica. 1991;6(3):44–6.

Murty DS. Heterosis, combining ability and reciprocal effects for agronomic and chemical characters in sesame. Theor Appl Genet. 1975;45(7):294–9.

Tu L, Liang X, Wang W, Zheng Y, Liu J. Studies on genetic male sterility in sesame (Sesamum indicum L.). Acta Agriculturae Boreali-Sinica. 1995;10(1):34–9.

Wang Q, Wenxin CAO, Guizhen XU. Study on the recessive-male sterile lines (0176A,54-8 A) and their utilization in sesame breeding. Chin J Oil Crop Sci. 2007;29(2):157–61.

Zhao YZ, Yang MM, Wu K, Liu HY, Wu JS, Liu KD. Characterization and genetic mapping of a novel recessive genic male sterile gene in sesame (Sesamum indicum L.). Mol Breed. 2013;32(4):901–8.

Zhou T, Hao G, Yang Y, Liu H, Yang M, Zhao Y. Sicwinv1, a cell wall invertase from sesame, is involved in anther development. J Plant Growth Regul. 2019;38(4):1274–86.

Jez JM, Bowman ME, Dixon RA, Noel JP. Structure and mechanism of the evolutionarily unique plant enzyme chalcone isomerase. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7(9):786–91.

Hopwood DA. Genetic contributions to understanding polyketide synthases. Chem Rev. 1997;97(7):2465–97.

Shen B, Cheng Y-Q, Christenson SD, Jiangi H, Ju J, Kwon H-J, et al. Polyketide biosynthesis beyond the type I, II, and III polyketide synthase paradigms: a progress report. In: Rimando AM, Baerson SR, editors. Polyketides: Biosynthesis, Biological Activity, and Genetic Engineering, vol. 955; 2007. p. 154–66.

Abe I, Utsumi Y, Oguro S, Morita H, Sano Y, Noguchi H. A plant type III polyketide synthase that produces pentaketide chromone. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127(5):1362–3.

Austin MB, Bowman ME, Ferrer JL, Schroder J, Noel JP. An aldol switch discovered in stilbene synthases mediates cyclization specificity of type III polyketide synthases. Chem Biol. 2004;11(9):1179–94.

Wu Y, Ling M, Wu Z, Li Y, Zhu L, Yang X, et al. Defective pollen wall contributes to male sterility in the male sterile line 1355A of cotton. Sci Rep. 2015;5:9608.

Wan XY, Wu SW, Li ZW, An XL, Tian YH. Lipid Metabolism: Critical Roles in Male Fertility and Other Aspects of Reproductive Development in Plants. Mol Plant. 2020;13(7):955–83.

Lescot M, Dehais P, Thijs G, Marchal K, Moreau Y, Van de Peer Y, et al. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30(1):325–7.

Higo K, Ugawa Y, Iwamoto M, Korenaga T. Plant cis-acting regulatory DNA elements (PLACE) database: 1999. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27(1):297–300.

Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35(6):1547–9.

Yang XY, Li JG, Pei M, Gu H, Chen ZL, Qu LJ. Over-expression of a flower-specific transcription factor gene AtMYB24 causes aberrant anther development. Plant Cell Rep. 2007;26(2):219–28.

Wang Y, Li Y, He SP, Gao Y, Wang NN, Lu R, et al. A cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) WRKY transcription factor (GhWRKY22) participates in regulating anther/pollen development. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2019;141:231–9.

Clough SJ, Bent AF. Floral dip: A simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998;16:735–43.

Li D, Liu P, Yu J, Wang L, Dossa K, Zhang Y, et al. Genome-wide analysis of WRKY gene family in the sesame genome and identification of the WRKY genes involved in responses to abiotic stresses. BMC Plant Biol. 2017;17:152.

Czechowski T, Stitt M, Altmann T, Udvardi MK, Scheible WR. Genome-wide identification and testing of superior reference genes for transcript normalization in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2005;139:5–17.

Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C-T method. Nat Protoc. 2008;3(6):1101–8.

Acknowledgments

We thank all of the laboratory members for their collaboration and constructive suggestions.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31701468, No. 31771877), China Agriculture Research System of MOF and MARA (CARS-14), and the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Project of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS-ASTIP-2013-OCRI).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TYL, TZ, and YZZ conceived and designed the project and experiments. TYL and YXY performed the experiments. TYL analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. HYL and FZ assisted in preparing the materials. YZZ, TZ, and DSSK revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Study complied with local and national regulations for using plants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplementary Table 1.

Primers used for RT-PCR and qRT-PCR. Supplementary Table 2. SiPKSA cis-acting elements potentially associated with the anther development. Supplementary Table 3. Real time data and statistical analysis. Supplementary Figure 1. Expression analysis of AtPKSA in WT, EV and transgenic Arabidopsis. Supplementary Figure 2. The uncropped gel of the RT-PCR result of SiPKSA expression in different tissues of sesame. Supplementary Figure 3. The uncropped gel of the RT-PCR result of the expression of SiPKSA in sesame fertile and sterile anthers at different developmental stages. Supplementary Figure 4. The uncropped gel of the RT-PCR result of SiPKSA in SiPKSA-overexpressing lines. Supplementary Figure 5. The uncropped gel of the RT-PCR result of the expression of AtPKSA in SiPKSA-overexpressing lines.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, T., Yang, Y., Liu, H. et al. Overexpression of sesame polyketide synthase A leads to abnormal pollen development in Arabidopsis. BMC Plant Biol 22, 165 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-022-03551-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-022-03551-7