Abstract

Background

Trees of Bombax ceiba L. could produce a large number of viable seeds in the dry-hot valleys. However, the seedling regeneration of the species is difficult in these areas as mild drought often occur repeatedly which might be followed by heat stress. However, how the repeated drought affects the subsequent drought and heat tolerance of B. ceiba is not clear. In this study, chlorophyll fluorescence, soluble sugar content and lipid metabolism were measured for the drought-treated seedlings and heat-treated seedlings with or without drought hardening.

Results

Neither the first nor third dehydration treatments affected the photosynthetic activity and soluble sugar content of B. ceiba seedlings. However, they differentially affected the fluidity of the local membranes and the levels of diacylglycerol and phosphatidic acid. Heat shock severely decreased the photosynthetic efficiency but drought priming reduced the effects of heat shock. Moreover, heat shock with or without drought priming had differential effects on the metabolism of soluble sugars and some lipids. In addition, the unsaturation level of membrane glycerolipids increased following heat shock for non-drought-hardened seedlings which, however, maintained for drought-hardened seedlings.

Conclusions

The results suggest that two cycles of dehydration/recovery can affect the metabolism of some lipids during the third drought stress and may enhance the heat tolerance of B. ceiba by adjusting lipid composition and membrane fluidity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Drought and high temperatures are two key factors affecting plant productivity and survival due to the accumulation of reactive oxygen species, enzyme inactivation, protein denaturation and disruption of membrane structures [1, 2]. Thylakoid membranes are the primary sites sensing environmental conditions and photosynthesis is the most sensitive process to drought and heat [3,4,5]. In fact, chlorophyll fluorescence parameters and photosynthesis are often used to reflect the sensitivity of plants to various types of stresses and stress intensities.

Plants have evolved various strategies to alleviate the harmful effects of drought and heat through changes in their physiological, metabolic and molecular characteristics [1, 2]. For example, the accumulation of soluble sugars, the improvement of antioxidant enzyme activities and the increased heat dissipation are often involved in the tolerance of plants to drought and heat [1, 2]. In nature, these abiotic stresses might occur individually or sequentially. Due to their unpredictable nature, plants have evolved stress memory mechanisms by which they can remember past stress events and prime their responses to react more rapidly or strongly to future stresses [5, 6]. Stress memory involves multiple modifications at physiological, proteomic, transcriptional levels and epigenetic mechanisms [6]. In this sense, drought hardening could improve the tolerance of some plants to subsequent drought events or induce cross-tolerance to other stresses including heat and freezing [7, 8].

The membrane is particularly susceptible to injury from adverse temperatures [9, 10]. Therefore, the temperature-compatible fluidity and integrity of membranes are essential to maintain the healthy structure and function of plant cells under varying temperatures [11]. Lipids are essential constituents of membrane systems and are also involved in energy storage and signal transduction. Lipid composition widely vary in membranes, tissues, species, and developmental stages, and are also influenced by environmental conditions [12, 13]. The changes of lipid metabolism of plants under drought and heat stress have been studied [10, 13]. Lipid metabolism under drought stress can vary depending on the plant species and drought intensity [13, 14]. The composition and unsaturation level of lipids are associated with membrane fluidity. This, in turn, is closely related to the plant tolerance to extreme temperatures [10, 15]. The heat sensitivity of plants is associated with lipid desaturation [10, 16]. However, the changes in lipid metabolism following repeated and combined stresses, and its role in the induction of cross-tolerance are unclear.

The dry-hot valleys in China have a harsh climate, fragile geological structure and severely degraded vegetation [17, 18]. High temperatures in these areas can exceed 40 °C and the dry season can be six months or longer [19]. Even during the wet season, water stress can occur due to the high rate of evapotranspiration [20]. The type of vegetation present in the dry-hot valleys is restricted to the degraded secondary vegetation. To make matters worse, vegetation restoration is difficult in these areas due to their severe environmental conditions [18]. Bombax ceiba L. is a multi-use tree species with high ornamental and economic values [21, 22]. B. ceiba can grow up to an average of 20 m in these areas and can produce a large number of viable seeds. This suggests good adaptation to the local conditions. However, its natural regeneration by seedlings is difficult in the dry-hot valleys. As a matter of fact, studies have shown that seedling establishment is especially sensitive to environmental changes [23]. However, the response and adaptation of B. ceiba seedlings to drought and heat stress is not well understood.

In dry-hot valleys, mild droughts often occur repeatedly, and they may be followed by heat stress. We hypothesized that repeated mild droughts might modify the biochemical and physiological characteristics, and affect the response and adaptation of B. ceiba to drought and heat stress. We therefore studied 1) the effects of repeated droughts on the physiological characteristics and lipid metabolism of B. ceiba under subsequent drought conditions, and 2) the effects of repeated drought on heat tolerance of B. ceiba. The results can provide a guide for the adaptive mechanisms of B. ceiba to the environmental conditions of dry-hot valleys and the reforestation in these areas.

Results

Effects of drought and heat on chlorophyll fluorescence

None of the chlorophyll fluorescence parameters changed after the first (D1) and third (D3) dehydration stress, in comparison with the control (Table 1; Additional file 1). Compared to the control, the maximum chlorophyll fluorescence (Fm), the maximum quantum yield of photosystem II (PSII) (Fv/Fm), effective quantum yield of PS II (Y(II)), photochemical quenching coefficient (qP), relative electron transport rate (rETR), regulated non-photochemical energy loss in PS II (Y(NPQ)) and non-photochemical quenching coefficient (qN) decreased after individual heat shock (H), by 52.53, 35.98, 60.18, 45.56, 60.54, 69.95 and 58.79% respectively. The non-regulated non-photochemical energy loss in PS II (Y(NO)) increased by 76.22% following H treatment when compared to the control (Table 1; Additional file 1). Additionally, ground fluorescence (Fo) did not change after H treatment but increased by 28.66% after two cycles of dehydration/recovery followed by H treatment (D2H), in comparison with the control (Additional file 1). Compared to the H treatment, Y(NO) decreased by 27.23% but Fo, Fm, Fv/Fm, Y(II), qP, ETR, Y(NPQ) and qN increased following D2H treatment, by 24.59, 45.65, 14.66, 77.78, 81.63, 77.59, 153.60 and 121.76% respectively .

Seedlings were subjected to air drying for 2 h at 28 °C (the first dehydration stress, D1) followed by full rehydration recovery for 22 h. After two cycles of dehydration/rehydration, seedlings were exposed to the third dehydration stress (D3) or treated at 48 °C for 2 h (D2H). Heat-treated seedlings (H) were directly treated at 48 °C. Within the same experiment, different letters in the same row indicate significant differences between treatments (P < 0.05). Data are represented as mean ± standard deviation (n = 5). rETR: Relative electron transport rate; Fv/Fm: The maximum quantum yield of photosystem II (PSII); qP: Photochemical quenching coefficient; qN: Non-photochemical quenching coefficient; Y(II): Effective quantum yield of PS II; Y(NO): Non-regulated non-photochemical energy loss in PS II; Y(NPQ): Regulated non-photochemical energy loss in PS II.

Effects of drought and heat on soluble sugar content

Compared to the control, both D1 and D3 treatments did not change the soluble sugar content of the seedlings of B. ceiba (Fig. 1a). Soluble sugars increased by 136.41% after H treatment but was maintained after D2H treatment, in comparison with the control (Fig. 1b).

Changes of soluble sugar content in Bombax ceiba L. treated with dehydration and heat shock. Seedlings were subjected to air drying for 2 h at 28 °C (the first dehydration stress, D1) followed by full rehydration recovery for 22 h. After two cycles of dehydration/rehydration, seedlings were exposed to the third dehydration stress (D3) or treated at 48 °C for 2 h (D2H). Heat-treated seedlings (H) were directly treated at 48 °C. Within the same experiment, different letters indicate significant differences between treatments (P < 0.05). Data are represented as mean ± standard deviation (n = 5)

Composition of the main lipid categories

Eight main lipid categories including 24 lipid classes and 463 lipid species were determined (Additional file 2). In the dehydration-treated seedlings, the content of most of the lipid categories did not change after the D1 and D3 treatments when compared to the control (Table 2). Compared to the control, the levels of neutral glycerolipids did not change after D1 treatment but increased by 169.15% after D3 treatment. Accordingly, the content of diacylglycerol (DAG) increased by 218.96% in D3-treated seedlings, in comparison with the control (DAG; Additional file 3). In addition, compared to the control, the content of lysophospholipids increased after D1 and D3 treatments, by 100 and 109.09% respectively. The total lipids accumulated greatly (by 83.45%) following D3 treatment when compared to the control. For the heat-treated seedlings, the contents of both the phospholipids and lysophospholipids increased only at D2H treatment, by 86.47 and 100% respectively, in comparison with the control (Table 2). However, compared to the control, neutral glycerolipids and fatty acyls accumulated only at H treatment, by 82.33 and 100% respectively. Accordingly, the content of triacylglycerol (TAG) increased by 317.59% in H-treated seedlings when compared to the control (Additional file 3). Compared to the control, the levels of saccharolipids, sphingolipids, sterol lipids, prenol lipids, and the total lipids increased by 121.13, 55.88, 127.60, 67.21 and 87.17% respectively after H treatment and increased by 117.22, 38.36, 74.80, 86.89 and 72.79% respectively after D2H treatment.

Seedlings were subjected to air drying for 2 h at 28 °C (the first dehydration stress, D1) followed by full rehydration recovery for 22 h. After two cycles of dehydration/rehydration, seedlings were exposed to the third dehydration stress (D3) or treated at 48 °C for 2 h (D2H). Heat-treated seedlings (H) were directly treated at 48 °C. Within the same experiment, different letters in the same row indicate significant differences between treatments (P < 0.05). Data are represented as mean ± standard deviation (n = 5).

Composition of membrane glycerolipids

In the dehydration-treated seedlings, the phosphatidic acid (PA) content did not change after D1 treatment but increased by 64.66% following D3 treatment, in comparison with the control (Table 3). Compared to the control, lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC), lysophosphatidylglycerol (LPG), and monogalactosylmonoacylglycerol (MGMG) increased by 95.99, 94.28 and 200% respectively following D1 treatment and increased by 67.36, 100.62 and 174.19% respectively following D3 treatment. However, the content of other lipid classes of membrane glycerolipids did not vary in response to the dehydration treatments in comparison with the control. The contents of the main lipid species following different dehydration treatments are presented in Figs. 2 and 3.

Changes of the main lipid molecular species of phospholipids and lysophospholipids in Bombax ceiba L. treated with dehydration and heat shock. Seedlings were subjected to air drying for 2 h at 28 °C (the first dehydration stress, D1) followed by full rehydration recovery for 22 h. After two cycles of dehydration/rehydration, seedlings were exposed to the third dehydration stress (D3) or treated at 48 °C for 2 h (D2H). Heat-treated seedlings (H) were directly treated at 48 °C. Within the same lipid species, * indicate significant variations among treatments (P < 0.05). Data are represented as mean ± standard deviation (n = 5)

Changes of the main lipid molecular species of saccharolipids in Bombax ceiba L. treated with dehydration and heat shock. Seedlings were subjected to air drying for 2 h at 28 °C (the first dehydration stress, D1) followed by full rehydration recovery for 22 h. After two cycles of dehydration/rehydration, seedlings were exposed to the third dehydration stress (D3) or treated at 48 °C for 2 h (D2H). Within the same lipid species, * indicate significant variations among treatments (P < 0.05). Heat-treated seedlings (H) were directly treated at 48 °C. Data are represented as mean ± standard deviation (n = 5)

Compared to the control, the contents of phosphatidylinositol (PI) and phosphatidylinositol phosphate (PIP) increased by 37.91 and 220.00% respectively after H treatment and all the other lipid classes of phospholipids and lysophospholipids increased significantly following D2H treatment (Table 3). Compared to the control, MGDG, DGDG, and SQDG increased by 115.16, 122.88 and 120.12% respectively after H treatment and increased by 99.31, 92.44 and 148.99% respectively after D2H treatment but MGMG content only increased (by 303.23%) following H treatment. The contents of the main lipid species following different heat treatments are presented in Figs. 2 and 3.

Seedlings were subjected to air drying for 2 h at 28 °C (the first dehydration stress, D1) followed by full rehydration recovery for 22 h. After two cycles of dehydration/rehydration, seedlings were exposed to the third dehydration stress (D3) or treated at 48 °C for 2 h (D2H). Heat-treated seedlings (H) were directly treated at 48 °C. Within the same experiment, different letters in the same row indicate significant differences between treatments (P < 0.05). Data are represented as mean ± standard deviation (n = 5). CL: Cardiolipin; DGDG: Digalactosyldiacylglycerol; LPC: Lysophosphatidylcholine; LPG: Lysophosphatidylglycerol; MGDG: Monogalactosyldiacylglycerol; MGMG: monogalactosylmonoacylglycerol; PA: Phosphatidic acid; PC: Phosphatidylcholine; PE: Phosphatidylethanolamine; PG: Phosphatidylglycerol; PI: Phosphatidylinositol; PIP: Phosphatidylinositol phosphate; PS: Phosphatidylserine; SQDG: Sulphoquinovosyldiacylglycerol.

The acyl chain length (ACL) and double bond index (DBI) of membrane glycerolipids

Compared to the control, the ACL increased by 0.29% in PG following D1 treatment, increased in PIP following D1 and D3 treatments (by 0.25 and 0.13%, respectively), and remained unchanged in all the other lipid classes of membrane glycerolipids (Table 4). The ACL of the total phospholipids and the total lysophospholipids did not change after D1 and D3 treatments when compared to the control (Table 4). Compared to the control, the ACL of the total saccharolipids and the total membrane glycerolipids decreased by 1.24 and 0.77% respectively after D1 treatment but remained unchanged after D3 treatment. For the heat-treated seedlings, the ACL increased by 0.20% in PIP after H treatment and increased by 0.41% in CL and decreased by 1.09% in PA after D2H treatment, in comparison with the control. Compared to the control, the ACL of the total phospholipids increased by 1.06% after H treatment but decreased by 1.01% after D2H treatment. The ACL of MGMG, MGDG, and DGDG increased only following H treatment, by 1.13, 0.54 and 0.42% respectively. The ACL of the total saccharolipids and the total membrane glycerolipids remained unchanged following both heat treatments.

Seedlings were subjected to air drying for 2 h at 28 °C (the first dehydration stress, D1) followed by full rehydration recovery for 22 h. After two cycles of dehydration/rehydration, seedlings were exposed to the third dehydration stress (D3) or treated at 48 °C for 2 h (D2H). Heat-treated seedlings (H) were directly treated at 48 °C. Within the same experiment, different letters in the same row indicate significant differences between treatments (P < 0.05). Data are represented as mean ± standard deviation (n = 5). CL: Cardiolipin; DGDG: Digalactosyldiacylglycerol; LPC: Lysophosphatidylcholine; LPG: Lysophosphatidylglycerol; MGDG: Monogalactosyldiacylglycerol; MGMG: monogalactosylmonoacylglycerol; PA: Phosphatidic acid; PC: Phosphatidylcholine; PE: Phosphatidylethanolamine; PG: Phosphatidylglycerol; PI: Phosphatidylinositol; PIP: Phosphatidylinositol phosphate; PS: Phosphatidylserine; SQDG: Sulphoquinovosyldiacylglycerol.

For the drought-treated seedlings, the DBI of PIP increased following D1 and D3 treatments, by 14.22 and 9.04% respectively, in comparison with the control (Table 5). Compared to the control, the DBI of the total phospholipids remained unchanged after D1 treatment but increased by 6.41% after D3 treatment. The DBI increased by 11.88% in DGDG only after D1 treatment but did not change in the total saccharolipids after D1 and D3 treatments. Additionally, the DBI of the total membrane glycerolipids did not change following different dehydration treatments when compared to the control. For heat-shock treated seedlings, the DBI of PA decreased by 6.95% after H treatment and decreased by 15.68% after D2H treatment, in comparison with the control (Table 5). Compared to the control, the DBI increased by 15.73% in PIP after H treatment and increased by 1.37% in CL after D2H treatment. The DBI of the total phospholipids and lysophospholipids did not change following H treatment but decreased following D2H treatment, by 12.48 and 23.68% respectively, in comparison with the control. Compared to the control, the DBI increased in MGMG and DGDG (by 26.26 and 13.56%, respectively) only after H treatment but remained unchanged in the total saccharolipids following H and D2H treatments. The DBI of the total membrane glycerolipids increased by 10.40% after H treatment but did not change following D2H treatment when compared to the control.

Seedlings were subjected to air drying for 2 h at 28 °C (the first dehydration stress, D1) followed by full rehydration recovery for 22 h. After two cycles of dehydration/rehydration, seedlings were exposed to the third dehydration stress (D3) or treated at 48 °C for 2 h (D2H). Heat-treated seedlings (H) were directly treated at 48 °C. Within the same experiment, different letters in the same row indicate significant differences between treatments (P < 0.05). Data are represented as mean ± standard deviation (n = 5). CL: Cardiolipin; DGDG: Digalactosyldiacylglycerol; LPC: Lysophosphatidylcholine; LPG: Lysophosphatidylglycerol; MGDG: Monogalactosyldiacylglycerol; MGMG: monogalactosylmonoacylglycerol; PA: Phosphatidic acid; PC: Phosphatidylcholine; PE: Phosphatidylethanolamine; PG: Phosphatidylglycerol; PI: Phosphatidylinositol; PIP: Phosphatidylinositol phosphate; PS: Phosphatidylserine; SQDG: Sulphoquinovosyldiacylglycerol.

Discussion

Photosynthesis is the most sensitive process to various environmental stresses. Photosynthetic efficiency typically decreases before changes in other physiological processes can be detected [4]. Among the photosynthetic process components, photosystem II is the most sensitive to stresses such as drought and heat [24, 25]. Therefore, chlorophyll fluorescence is often used to reflect the physiological status of plants under stress [26,27,28]. The maintenance of chlorophyll fluorescence parameters following the first and third dehydration treatments showed that the photosynthetic process of B. ceiba was not affected and that the intensity of the dehydration treatments was mild.

Healthy plants adapted to darkness have Fv/Fm ratios ranging from 0.75 to 0.85 [29]. The substantial decrease of Fv/Fm under H treatment suggests that heat shock induced severe photoinhibition of B. ceiba. A decreased Fv/Fm is associated with the damage to the PSII reaction center or the enhanced thermal dissipation of excitation energy [30, 31]. Based on the decline of qN, the photosynthetic apparatus was not protected against photodamage through heat dissipation, and therefore the decrease of Fv/Fm was likely due to the injury of the PSII reaction center induced by the H treatment. The increase of Y(NO) and decrease of Y(NPQ) during H treatment also implied that the excess excitation energy cannot be safely dissipated [32, 33]. The sharp reduction of qP, Y(II) and rETR confirm that heat stress severely decreased the photosynthetic activity. In this way, the absorbed excessive energy may have led to the accumulation of reactive oxygen species, which might have further disrupted the membrane structure and damaged some heat-sensitive components of the photosynthetic apparatus such as the oxygen-evolving complex and D1 protein [34, 35].

Furthermore, Fm decreased significantly after H treatment (Additional file 1). Decreased Fm has been ascribed to the degradation of light-harvesting antenna or the activity loss of the oxygen-evolving complex [36, 37]. However, the decrease of Fm and increase of Fo following D2H treatment indicated that B. ceiba seedlings initiated photoprotection mechanisms through the reversible inactivation of photosynthetic reaction center [38, 39]. In addition, the decrease of Y(NO) and increases of all the other chlorophyll fluorescence parameters following D2H compared with H suggest that the impairing effects of heat shock on photosynthesis can be reduced by pre-exposure to repeated mild droughts in B. ceiba. Other studies have also demonstrated that drought preconditioning can improve plant tolerance to heat stress [40]. The drought hardening might induce adjustments of plants at physiological, metabolic, and molecular levels, and these might contribute to the induced tolerance to subsequent stresses [41].

Regulation of stress priming and memory occurs at the levels of transcription, translation, and protein phosphorylation as well as at the metabolite level [6]. The multipurpose sugar and lipid metabolites are important in the plant adaptation to environmental changes [42, 43]. However, the involvement of sugars and lipids in the regulation of stress priming and memory is poorly documented.

Nonstructural carbohydrates serve as building blocks for plant growth and are also involved in signal transduction, osmosis, and energy metabolism [44]. Therefore, carbohydrate metabolism plays a crucial role in plant function and survival which is regulated by environmental conditions [45]. The content of soluble sugars did not change following D1 and D3 treatments. Considering the maintenance of photosynthetic activity, we postulate that the mild dehydration treatment may not have affected the sugar metabolism of B. ceiba. Nevertheless, heat stress can induce the reprogramming of carbohydrate metabolism [46]. The accumulation of soluble sugars under heat stress was also found in Nouelia insignis [47]. As the photosynthetic activity of B. ceiba decreased severely after H treatment, the enhanced de novo synthesis was unlikely to be a reason for the substantial increase of the soluble sugars. This was probably due to the inhibition of the conversion of sugars into starch and/or the reduced translocation from leaves to the roots [46, 48]. The accumulated soluble sugars might help to defend against high temperature stress serving as antioxidants, osmoprotectants, and signaling molecules [42, 49]. Drought priming inhibited the increment of soluble sugars during subsequent heat stress. This might be due to the fact that D2H treatment did not affect the activities of the enzymes/proteins involved in the sugar transfer and starch synthesis, such as sucrose transporters and starch synthase [50]. However, this should be further confirmed through determination of the metabolic reprogramming of carbohydrates and the related enzyme activities in those processes.

DAG and PA are the intermediates of lipid biosynthesis and also important second messengers that help to regulate cell functions [43, 51, 52]. Without degradation of other lipid classes, the substantial production of DAG under D3 treatment (Additional file 3) may have been due to an increased de novo synthesis. PA is produced through the phosphorylation of DAG or the hydrolysis of phospholipids and its synthesis can be induced by many types of stresses including chilling, freezing, drought and salinity [15, 53,54,55]. According to the maintenance of other lipid classes, the accumulation of PA in the plants subjected to D3 treatment may have resulted from the conversion of DAG, whose levels were also enhanced in this treatment [56]. As DAG can be further phosphorylated by DAG kinases to generate PA [57], its role in plants remains elusive [43]. However, the accumulation of DAG following D3 treatment might enable plants to marshal a rapid and strong response to subsequent stress by providing energy, carbon and signaling molecules. PA is also involved in plant development and response to environmental stresses [52]. For example, some studies have shown that PA plays important roles in plant tolerance to dehydration [55]. The accumulation of DAG and PA following D3 treatment indicated that lipid signaling participates in the adaptation of B. ceiba to repeated drought stress.

Lysophospholipids have a dual role in plant cells: at low concentrations they can function as signaling molecules, while at high doses, they can be deleterious to cells [43, 58]. These lipids usually increase upon exposure to stresses such as freezing temperatures, wound and potassium deficiency [53, 58, 59]. The transient increase of lysophospholipids has been reported to be involved in the plant defense response [59, 60]. The time course of changes in lysophospholipids of B. ceiba was not determined, therefore whether the accumulation of these lipids following D1 and D3 treatments was transient is not clear. As the intensity of the dehydration was mild, we hypothesize that the increase of lysophospholipids following D1 and D3 treatments may have helped B. ceiba to adapt to the moderate changes in moisture conditions.

The levels of ACL and DBI can reflect membrane fluidity, which, in turn, affects the adaptability of plants to environmental stresses [15]. Some studies have demonstrated that the drought-enhanced membrane fluidity through adjusting lipid unsaturation level contributes to drought stress resistance [61, 62]. The decreased ACL of the total saccharolipids indicates that the fluidity of plastidic membranes in B. ceiba decreased following D1 treatment. However, the increased DBI of phospholipids suggests that the fluidity of the extraplastidic membranes increased after D3 treatment. It can be seen that D1 and D3 treatments had differential impacts on the local membrane fluidity. Moreover, the different adjustments of DAG, PA, and membrane fluidity between D1 and D3 demonstrate that two cycles of drought/recovery affected lipid metabolism during subsequent drought stress.

TAG plays an important role in stabilizing membranes, protecting cells against photodamage and consuming excessive photoassimilates [51, 63, 64]. It has been reported that heat can induce the accumulation of TAG and the conversion of DAG to TAG can augment plant thermotolerance [65, 66]. Cuticular waxes are major components of the cuticle and are involved in protecting plants against various stresses, including drought, cold and physical damage [67,68,69]. Cuticular waxes can reduce water loss and function as a photoprotective layer [68, 69]. The accumulation of TAG and wax esters (Table 2; Additional file 3) might be positive defense responses of B. ceiba to H treatment.

Phospholipids are important structural components of membranes, signaling molecules, and an energy source [13, 70]. Compared to the H treatment, the accumulation of phospholipids and lysophospholipids during D2H suggests that the induced thermotolerance by drought hardening might be related to the adjustment of phospholipid metabolism. The registered increase in DAG content in D3-treated plants may have been induced by previous repeated dehydration (Additional file 3), but whether the accumulated phospholipids were converted from the DAG induced during drought hardening needs verification. Among the classes of phospholipids, PI and PIP are components of the PI signal system involved in the perception and transduction of environmental stimuli [71]. The induction of PI and PIP by H treatment suggests that the PI signal pathway is involved in the response and adaptation of B. ceiba to sudden heat shock. PA is also an important signaling molecule which is involved in the plant tolerance to drought and heat [55, 72]. H and D2H treatments imposed different effects on the contents of PA, PI and PIP when compared to the control (Table 3). This indicates that phospholipid signaling pathway might be involved in the drought-induced thermotolerance of B. ceiba. Zhang et al. [40] also reported that the reprogramming of lipid metabolism for phospholipid signaling could contribute to drought priming (without a recovery period)-enhanced heat tolerance in Festuca arundinacea. The differential modifications of TAG, wax esters and phospholipids between H and D2H might underlie the enhanced thermotolerance enabled by drought hardening.

Besides PG, saccharolipids are major plastidic lipids that are essential to maintain the normal photosynthetic process [73, 74]. However, PG and saccharolipids are readily degraded under many abiotic stresses including heat, γ-ray and drought [13, 75, 76]. Following both heat treatments, the accumulation of PG and saccharolipids may have helped to stabilize or repair the heat-sensitive thylakoid membranes [77]. We hypothesize that this might be related to the long-term adaptation of this species to the high temperatures in their habitats. Although accounting for very small fractions of lipids, sphingolipids, sterols and prenol lipids play crucial roles in maintenance of cellular processes. Both sphingolipids and sterols are structural components of membranes and signaling molecules [43, 78, 79]. Prenol lipids can function as antioxidants and play a role in energy metabolism [80]. However, the association between these lipids and heat tolerance in plants has rarely been documented. The induction of these lipids following H and D2H treatments might be common defense reactions that seedlings of B. ceiba use to resist heat shock.

The increase of ACL and decrease of DBI levels have been associated with the maintenance of cell membrane stability under high temperatures [81, 82]. Thylakoid membrane stability limits photosynthetic performance [83]. For example, the rapid saturation of thylakoid-associated fatty acids is important for ultrastructure maintenance in a marine diatom [84]. Based on the maintenance of ACL and DBI levels, it can be further discussed that the photosynthetic membranes of B. ceiba possess a certain degree of stability under heat stress, which confers the basal thermotolerance in B. ceiba. The changes of ACL and DBI of phospholipids presented a similar trend among heat treatments (Tables 4 and 5). However, the significantly lower DBI/ACL (Additional file 4) showed that the fluidity of extraplastidic membranes decreased following D2H treatment. According to the DBI of the total membrane glycerolipids, H treatment increased the membrane fluidity of B. ceiba; however, pre-exposure to dehydration could offset heat effects on membranes. Therefore, drought hardening could improve the local membrane stability of B. ceiba during the subsequent heat shock. The results were consistent with those of the chlorophyll fluorescence, which suggested the amelioration of the impairing effects of heat on photosynthetic activity by previous drought hardening. We inferred that the drought priming-enhanced heat tolerance was associated with the improved membrane stability in B. ceiba.

Conclusions

Two cycles of dehydration/recovery affected the fluidity of local membranes and the metabolism of DAG and PA during the third drought stress in B. ceiba seedlings. Pre-exposure of seedlings to two cycles of dehydration/recovery ameliorated the impairing effects of heat shock on photosynthesis. Seedlings of B. ceiba presented differential responses to heat shock with or without drought priming in the contents of soluble sugars, neutral glycerolipids, fatty acyls, phospholipids, and lysophospholipids. In addition, heat shock induced the instability of membranes but previous drought hardening seemed to stabilize membranes by affecting the membrane fluidity. In summary, two cycles of dehydration/recovery affected the metabolism of some lipids during subsequent drought and could enhance the heat tolerance of B. ceiba by adjusting lipid composition and membrane fluidity. Therefore, drought hardening might be useful in reforestation projects to reduce the mortality of seedlings during the hot summers in the dry-hot valleys.

Methods

Plant material, growth conditions and seedling treatments

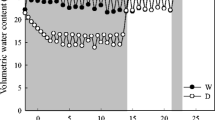

Bombax ceiba seeds were collected from 20 individual trees in a naturally distributed population at Gejiu, Yunnan province with permission from Forestry Bureau of Gejiu City. Germinated seedlings were cultivated in environment-controlled chambers where the culture conditions were 28 °C and 60% relative humidity with a 12:12 h photoperiod (250 μmol m− 2 s− 1). One-month-old seedlings were used as the experimental materials. The formal identification of the seedlings used in this study was performed by Shuang-zhi Li. Voucher specimens were deposited in the Southwest Forestry University. The dehydration stress procedures were performed using the methods of Ding et al. [85]. The seedlings were removed from the soil media and the roots were washed with water. Then the seedlings were acclimated for 24 h at 28 °C in jars with their roots in Hoagland solution [86]. Afterwards, seedlings were air dried for 2 h at 28 °C (the first dehydration stress, D1) followed by full rehydration recovery for 22 h at acclimation conditions. This constituted one stress/recovery cycle. After two cycles of treatments, seedlings were exposed to the third dehydration stress (D3) or treated at 48 °C for 2 h (D2H). Heat-treated seedlings (H) were directly treated at 48 °C. Seedlings that were not subjected to any treatment were used as the controls. Immediately following treatments, leaves of the control and treated plants were collected and frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at − 80 °C. Chlorophyll fluorescence parameters were measured as indicated below.

Two sets of experiments were designed. Control, D1, and D3 were compared to explore the effects of repeated drought (two cycles of drought/recovery) on physiological characteristics and lipid metabolism during subsequent drought; Control, H, and D2H were compared to study the effects of repeated drought on heat tolerance.

Measurement of chlorophyll fluorescence

Plants were placed in darkness for 30 min before measuring the chlorophyll fluorescence parameters using a pulse-amplitude modulation fluorometer (PAM-2500, Walz, Germany). The saturating light pulse was set at about 8000 μmol m− 2 s− 1 for 0.8 s. The actinic light was set at 269 μmol m− 2 s− 1 and the plants were adapted to such actinic light for 5 min. Maximum quantum yield of photosystem II (PSII) (Fv/Fm), actual photochemical quantum production of PS II (Y(II)), photochemical quenching coefficient (qP), non-photochemical quenching coefficient (NPQ), quantum yield of non-regulated non-photochemical energy dissipation (Y(NO)), quantum yield of regulated non-photochemical energy dissipation (Y(NPQ)) and relative electron transport rate (rETR) were measured. All the fluorescence parameters were given automatically by the instrument.

Measurement of soluble sugar content

Leaves (0.2 g) were sampled from four plants per treatment. The leaves were grinded with 5 ml of 10% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid and then centrifuged at 2012 g for 10 min. Two milliliters of the extract were added to 2 ml of 0.6% (w/v) thiobarbituric acid. The mixture was boiled for 30 min and then rapidly cooled in cold water. Absorbance was read at 450 nm using a spectrophotometer (uv-2450, Shimadzu, Japan). Soluble sugar content was expressed as mmol g− 1 fresh weight of leaves [86].

Lipid extraction, measurement and identification

Lipid extraction: Following being spiked with internal lipid standards (AVANTI, SPLASH LIPIDOMIX Mass Spec Standard, 330,707-1EA), the leaf sample was homogenized with 200 μL ultrapure water and 240 μL methanol (chromatographically pure). Eight hundred microliters of MTBE (chromatographically pure) were then added and ultrasounded for 20 min at 4 °C followed by sitting still for 30 min at room temperature. The solution was centrifuged at 14000 g for 15 min at 10 °C and the top organic phase containing lipid compounds was desiccated under nitrogen.

Lipid fraction measurement: reverse phase chromatography (UPLC system, Shimadzu, 30A) was selected for LC separation using CSH C18 column (1.7 μm, 2.1 mm × 100 mm, Waters). The lipid extracts were re-dissolved in 200 μL isopropanol/ acetonitrile (chromatographically pure, 9:1, v/v), centrifuged at 14000 g for 15 min, finally 3 μL of sample was injected. Solvent A was acetonitrile (chromatographically pure)–ultrapure water (6:4, v/v) with 0.1% formic acid (v/v) and 0.1 Mm ammonium formate and solvent B was acetonitrile-isopropanol (chromatographically pure, 1:9, v/v) with 0.1% formic acid (v/v) and 0.1 Mm ammonium formate. The initial mobile phase was 30% solvent B at a flow rate of 300 μL/min. It was held for 2 min, and then linearly increased to 100% solvent B in 23 min, followed by equilibrating at 5% solvent B for 10 min. Mass spectra was acquired by Q-Exactive Plus in positive and negative mode, respectively. ESI parameters were optimized and pre-set for all measurements as follows: Source temperature, 300 °C; Capillary Temp, 350 °C, the ion spray voltage was set at 3000 V, S-Lens RF Level was set at 50% and the scan range of the instruments was set at m/z 200–1800.

Lipid identification: The identification of lipid species was conducted applying “Lipid Search” based on MS/MS math and a mass tolerance of 5 ppm was used.

Calculation of lipid double bond index (DBI) and acyl chain length (ACL)

ACL = (∑[n × mol % lipid])/100, where n is the number of acyl carbons in each lipid molecule; DBI = (∑[N × mol % lipid])/100, where N is the number of double bonds in each lipid molecule [15].

Statistical analysis

There were five replicates in each treatment and each replicate comprised seven plants. Measurement of chlorophyll fluorescence was performed on one leaf of each plant for each replicate and sample collection for analysis of soluble sugar content and lipidomics was performed from three plants for each replicate. Data were analyzed by SPSS 16.0 software. One-way ANOVA was conducted on the data of Control, D1 and D3 and those of Control, H, and D2H. The statistical significance was tested by Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) method (P < 0.05). The results are means of five replicates (n = 5) ± standard deviation.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ACL:

-

Acyl chain length

- CL:

-

Cardiolipin

- DAG:

-

Diacylglycerol

- DBI:

-

Double bond index

- DGDG:

-

Digalactosyldiacylglycerol

- Fo:

-

The ground fluorescence

- Fv/Fm:

-

The maximum quantum yield of photosystem II (PSII)

- LPC:

-

Lysophosphatidylcholine

- LPG:

-

Lysophosphatidylglycerol

- MGDG:

-

Monogalactosyldiacylglycerol

- MGMG:

-

Monogalactosylmonoacylglycerol

- NPQ:

-

Non-photochemical quenching coefficient

- PA:

-

Phosphatidic acid

- PC:

-

Phosphatidylcholine

- PE:

-

Phosphatidylethanolamine

- PG:

-

Phosphatidylglycerol

- PI:

-

Phosphatidylinositol

- PIP:

-

Phosphatidylinositol phosphate

- PS:

-

Phosphatidylserine

- qP:

-

Photochemical quenching coefficient

- rETR:

-

Relative electron transport rate

- SQDG:

-

Sulphoquinovosyldiacylglycerol

- TAG:

-

Triacylglycerol

- Y(II):

-

Effective quantum yield of PS II

- Y(NO):

-

Non-regulated non-photochemical energy loss in PS II

- Y(NPQ):

-

Regulated non-photochemical energy loss in PS II

References

Kumar S, Sachdeva S, Bhat KV, Vats S. Plant responses to drought stress: physiological, biochemical and molecular basis. In: Vats S, editor. Biotic and abiotic stress tolerance in plants. Singapore: Springer; 2018.

Li ZG. Mechanisms of plant adaptation and tolerance to heat stress. In: Hasanuzzaman M, editor. Plant ecophysiology and adaptation under climate change: mechanisms and perspectives II. Singapore: Springer; 2020.

Krause GH, Weis E. Chlorophyll fluorescence and photosynthesis: the basics. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1991;42:313–49.

Brestic M, Zivcak M, Kalaji HM, Carpentier R, Allakhverdiev SI. Photosystem II thermostability in situ: environmentally induced acclimation and genotype-specific reactions in Triticumaestivum L. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2012;57:93–105.

Wang X, Li Z, Liu B, Zhou H, Elmongy MS, Xia Y. Combined proteome and transcriptome analysis of heat-primed azalea reveals new insights into plant heat acclimation memory. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:1278.

Hilker M, Schmülling T. Stress priming, memory, and signalling in plants. Plant Cell Environ. 2019;42:753–61.

Khan R, Ma X, Shah S, Wu X, Shaheen A, Xiao L, et al. Drought-hardening improves drought tolerance in Nicotiana tabacum at physiological, biochemical, and molecular levels. BMC Plant Biol. 2020;20:486.

Xu H, Li Z, Tong Z, He F, Li X. Metabolomic analyses reveal substances that contribute to the increased freezing tolerance of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) after continuous water deficit. BMC Plant Biol. 2020;20:15.

Hincha DK, Höfner R, Schwab KB, Heber U, Schmitt JM. Membrane rupture is the common cause of damage to chloroplast membranes in leaves injured by freezing or excessive wilting. Plant Physiol. 1987;83:251–3.

Djanaguiraman M, Boyle DL, Welti R, Jagadish SVK, Prasad PVV. Decreased photosynthetic rate under high temperature in wheat is due to lipid desaturation, oxidation, acylation, and damage of organelles. BMC Plant Biol. 2018;18:55.

Kuch A, Warnecke DC, Fritz M, Wolter FP, Heinz E. Strategies for increasing tolerance against low temperature stress by genetic engineering of membrane lipids. In: Terzi M, Cella R, Falavigna A, editors. Current issues in plant molecular and cellular biology. Dordrecht: Springer; 1995.

Liu M, Burgos A, Ma L, Zhang Q, Tang D, Ruan J. Lipidomics analysis unravels the effect of nitrogen fertilization on lipid metabolism in tea plant (Camellia sinensis L.). BMC Plant Biol. 2017;17:165.

Wang Y, Zhang X, Huang G, Feng F, Liu X, Guo R, et al. Dynamic changes in membrane lipid composition of leaves of winter wheat seedlings in response to PEG-induced water stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2020;20:84.

Perlikowski D, Kierszniowska S, Sawikowska A, Krajewski P, Rapacz M, Eckhardt A, et al. Remodeling of leaf cellular glycerolipid composition under drought and re-hydration conditions in grasses from the Lolium-Festuca complex. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1027.

Zheng G, Li L, Li W. Glycerolipidome responses to freezing-and chilling-induced injuries: examples in Arabidopsis and rice. BMC Plant Biol. 2016;16:70.

Alfonso M, Yruela I, Almarcegui S, Torrado E, Perez MA, Picorel R. Unusual tolerance to high temperatures in a new herbicide-resistant D1 mutant from Glycine max (L.) Merr. Cell cultures deficient in fatty acid desaturation. Planta. 2001;212:573–82.

Ma HC, McConchie JA. The dry-hot valleys and forestation in Southwest China. J For Res. 2001;12:35–9.

Zhang M, Li G, Huang W, Bi T, Chen G, Tang Z, et al. Proteomic study of Carissa spinarum in response to combined heat and drought stress. Proteomics. 2010;10:3117–29.

Li K, Liu FY, Zhang CH. Essential characteristic of climate and plant recovery in dry-hot valley. World Forestry Res. 2009;22:24–7.

Zhong XH. Degradation of ecosystem and ways of its rehabilitation and reconstruction in dry and hot valley-take representative area of jinsha river, Yunnan province as an example. Resour Environ Yangtze Basin. 2000;9:376–83.

Jain V, Verma SK, Sharma SK, Katewa SS, Bombax ceiba Linn. As an umbrella tree species in forests of southern Rajasthan, India. Res J Environ Sci. 2011;5:722–9.

Chaudhary PH, Khadabadi SS. Bombax ceiba Linn.: pharmacognosy, ethnobotany and phyto-pharmacology. Pharmacognosy. Communications. 2012;2:2–9.

Leck MA, Parker VT, Simpson RL. Seedling ecology and evolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2008.

Berry J, Björkman O. Photosynthetic response and adaptation to temperature in higher-plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 1980;31:491–543.

Murata N, Takahashi S, Nishiyama Y, Allakhverdiev SI. Photoinhibition of photosystem II under environmental stress. BBA-Bioenergetics. 2007;1767:414–21.

Nath K, O’Donnell JP, Lu Y. Chlorophyll fluorescence for high-throughput screening of plants during abiotic stress, aging, and genetic perturbation. In: Hou H, Najafpour M, Moore G, Allakhverdiev S, editors. Photosynthesis: structures, mechanisms, and applications. Cham: Springer; 2017.

Li Z, Tan XF, Lu K, Liu ZM, Wu LL. The effect of CaCl2 on calcium content, photosynthesis, and chlorophyll fluorescence of tung tree seedlings under drought conditions. Photosynthetica. 2017;55:553–60.

Watanabe E, Fekih R, Kasajima I. Advances in chlorophyll fluorescence theories: close investigation into oxidative stress and potential use for plant breeding. In: Panda S, Yamamoto Y, editors. Redox homeostasis in plants. Signaling and communication in plants. Cham: Springer; 2019.

Björkman O, Demmig B. Photon yield of O2 evolution and chlorophyll fluorescence characteristics at 77 K among vascular plants of diverse origins. Planta. 1987;170:489–504.

Duan W, Fan PG, Wang LJ, Li WD, Yan ST, Li SH. Photosynthetic response to low sink demand after fruit removal in relation to photoinhibition and photoprotection in peach trees. Tree Physiol. 2008;28:123–32.

Lamontagne M, Bigras FJ, Margolis HA. Chlorophyll fluorescence and CO2 assimilation of black spruce seedlings following frost in different temperature and light conditions. Tree Physiol. 2000;20:249–55.

Demmig-Adams B, Adams WW III. Photoprotection in an ecological context: the remarkable complexity of thermal energy dissipation. New Phytol. 2006;172:11–21.

Wang L. Physiological and molecular responses to variation of light intensity in rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis Muell. Arg.). PLoS One. 2014;9:e89514.

Li Y, Xu W, Ren B, Zhao B, Zhang J, Liu P, et al. High temperature reduces photosynthesis in maize leaves by damaging chloroplast ultrastructure and photosystem II. J Agron Crop Sci. 2020;206:548–64.

Li D, Wang M, Zhang T, Chen X, Li C, Liu Y, et al. Glycinebetaine mitigated the photoinhibition of photosystem II at high temperature in transgenic tomato plants. Photosynth Res. 2021;147:301–15.

Schreiber U, Berry JA. Heat induced changes in chlorophyll fluorescence in intact leaves correlated with damage of the photosynthetic apparatus. Planta. 1977;136:233–8.

Sundby C, Melis A, Mäenpää P, Andersson B. Temperature-dependent changes in the antenna size of photosystem II. Reversible conversion of photosystem IIα to photosystem IIβ. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Bioenergetics. 1986;851:475–83.

Ohad I, Adir N, Koike H, Kyle DJ, Inoue Y. Mechanism of photoinhibion in vivo. A reversible light-induced conformational change of reaction center II is related to an irreversible modification of the D1 protein. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:1972–9.

Xu AQ. Reversible inactivation of photosystem II reaction centers and its physiological significance. Plant Physiol Commun. 1999;35:273–6.

Zhang X, Xu Y, Huang B. Lipidomic reprogramming associated with drought stresspriming-enhanced heat tolerance in tall fescue (Festuca arundinacea). Plant Cell Environ. 2018;42:947–58.

Kozlowski TT, Pallardy SG. Acclimation and adaptive responses of woody plants to environmental stresses. Bot Rev. 2002;68:270–334.

Afzal S, Chaudhary N, Singh NK. Role of soluble sugars in metabolism and sensing under abiotic stress. In: Aftab T, Hakeem KR, editors. Plant growth regulators. Cham: Springer; 2021.

Hou Q, Ufer G, Bartels D. Lipid signalling in plant responses to abiotic stress. Plant Cell Environ. 2016;39:1029–48.

Tixier A, Orozco J, Amico Roxas A, Earles JM, Zwieniecki MA. Diurnal variation in nonstructural carbohydrate storage in trees: remobilization and vertical mixing. Plant Physiol. 2018;178:1602–13.

Zhang T, Cao Y, Chen Y, Liu G. Non-structural carbohydrate dynamics in Robinia pseudoacacia saplings under three levels of continuous drought stress. Trees. 2015;29:1837–49.

Mathieu AS, Tinel C, Dailly H, Quinet M, Lutts S. Impact of high temperature on sucrose translocation, sugar content and inulin yield in Cichorium intybus L. var. sativum. Plant Soil. 2018;432:273–88.

Zheng YL, Xia ZN, Ma HC, Yu ZX. The combined effects of water deficit and heat stress on physiological characteristics of endangered Nouelia insignis. Acta Physiol Plant. 2019;41:177.

Krauss A, Marschner H. Growth rate and carbohydrate metabolism of potato tubers exposed to high temperatures. Potato Res. 1984;27:297–303.

Soares C, Carvalho MEA, Azevedo RA, Fidalgo F. Plants facing oxidative challenges—a little help from the antioxidant networks. Environ Exp Bot. 2019;161:4–25.

Börnke F, Sonnewald S. Biosynthesis and metabolism of starch and sugars. In: Ashihara H, Crozier A, Komamine A, editors. Plant metabolism and biotechnology: John Wiley & Sons; 2011.

vom Dorp K, Dombrink I, Dörmann P. Quantification of diacylglycerol by mass spectrometry. In: Munnik T, Heilmann I, editors. Plant lipid signaling protocols. Methods in molecular biology (Methods and Protocols), vol 1009. Totowa: Humana Press; 2013.

Wang X, Su Y, Liu Y, Kim SC, Fanella B. Phosphatidic acid as lipid messenger and growth regulators in plants. In: Wang X, editor. Phospholipases in plant signaling. Signaling and communication in plants, vol. 20. Berlin: Springer; 2014.

Welti R, Li W, Li M, Sang Y, Biesiada H, Zhou HE, et al. Profiling membrane lipids in plant stress responses: role of phospholipase D alpha in freezing-induced lipid changes in Arabidopsis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:31994–2002.

Zhang J, Fan R, Li W. Induction and degradation of phosphatidic acid in the response of plants to stresses. Chinese J Biochem Mol Biol. 2011;27:101–9.

Hong Y, Zhang W, Wang X. Phospholipase D and phosphatidic acid signaling in plant response to drought and salinity. Plant Cell Environ. 2010;33:627–35.

Tang F, Xiao Z, Sun F, Shen S, Chen S, Chen R, et al. Genome-wide identification and comparative analysis of diacylglycerol kinase (DGK) gene family and their expression profiling in Brassica napus under abiotic stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2020;20:473.

Arisz SA, Testerink C, Munnik T. Plant PA signaling via diacylglycerol kinase. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-molecular and cell biology of. Lipids. 2009;1791:869–75.

Wang DD, Zheng GW, Li WQ. Changes of membrane stability in potassium- stressed plants. Plant Diversity Resour. 2014;36:595–602.

Lee S, Suh S, Kim S, Crain R, Kwak JM, Nam HG, et al. Systemic elevation of phosphatidic acid and lysophospholipid levels in wounded plants. Plant J. 1997;12:547–56.

Viehweger K, Dordschbal B, Roos W. Elicitor-activated phospholipase A2 generates lysophosphatidylcholines that mobilize the vacuolar H+ pool for pH signaling via the activation of Na+-dependent proton fluxes. Plant Cell. 2002;14:1509–25.

Toumi I, Gargouri M, Nouairi I, Moschou PN, Ben Salem-Fnayou A, Mliki A, et al. Water stress induced changes in the leaf lipid composition of four grapevine genotypes with different drought tolerance. Biol Plant. 2008;52:161–4.

Filek M, Walas S, Mrowiec H, Rudolphy-Skórska E, Sieprawska A, Biesaga-Kościelniak J. Membrane permeability and micro- and macroelement accumulation in spring wheat cultivars during the short-term effect of salinity- and PEG-induced water stress. Acta Physiol Plant. 2012;34:985–95.

Solovchenko AE. Physiological role of neutral lipid accumulation in eukaryotic microalgae under stresses. Russ J Plant Physiol. 2012;59:167–76.

Arisz SA, Heo J-Y, Koevoets IT, Zhao T, van Egmond P, Meyer AJ, et al. DIACYLGLYCEROL ACYLTRANSFERASE1 contributes to freezing tolerance. Plant Physiol. 2018;177:1410–24.

Mueller SP, Krause DM, Mueller MJ, Fekete A. Accumulation of extra-chloroplastic triacylglycerols in Arabidopsis seedlings during heat acclimation. J Exp Bot. 2015;66:4517–26.

Mueller SP, Unger M, Guender L, Fekete A, Muller MJ. Phospholipid: diacylglycerol acyltransferase-mediated triacylglyerol synthesis augments basal thermotolerance. Tree Physiol. 2017;175:486–97.

Zhou L, Ni E, Yang J, Zhou H, Liang H, Li J, et al. Rice OsGL1-6 is involved in leaf cuticular wax accumulation and drought resistance. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e65139.

Patwari P, Salewski V, Gutbrod K, Kreszies T, Dresen-Scholz B, Peisker H, et al. Surface wax esters contribute to drought tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2019;98:727–44.

Shepherd T, Griffiths QW. The effects of stress on cuticular waxes. New Phytol. 2006;171:469–99.

Cowan AK. Phospholipids as plant growth regulators. Plant Growth Regul. 2006;48:97–109.

Liu S, Hu Z, Zhang Q, Yang X, Critchley AT, Duan D. PI signal transduction and ubiquitination respond to dehydration stress in the red seaweed Gloiopeltis furcata under successive tidal cycles. BMC Plant Biol. 2019;19:516.

Chen J, Xu W, Burke JJ, Xin Z. Role of phosphatidic acid in high temperature tolerance in maize. Crop Sci. 2010;50:2506–15.

Dörmann P, Benning C. Galactolipids rule in seed plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2002;7:112–8.

Demé B, Cataye C, Block MA, Maréchal E, Jouhet J. Contribution of galactoglycerolipids to the 3-dimensional architecture of thylakoids. FASEB J. 2014;28:3373–83.

Zheng G, Li W. Profiling membrane glycerolipids during γ-ray-induced membrane injury. BMC Plant Biol. 2017;17:203.

Narayanan S, Tamura PJ, Roth MR, Prasad PVV, Welti R. Wheat leaf lipids during heat stress: I. high day and night temperatures result in major lipid alterations. Plant Cell Environ. 2016;39:787–803.

Yu B, Benning C. Anionic lipids are required for chloroplast structure and function in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2003;36:762–70.

Volkman JK. Sterols in microorganisms. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2003;60:495–506.

Luttgeharm KD, Kimberlin AN, Cahoon EB. Plant sphingolipid metabolism and function. In: Nakamura Y, Li-Beisson Y, editors. Lipids in plant and algae development. Subcellular biochemistry, vol. 86. Cham: Springer; 2016.

Hayashi K, Ogiyama Y, Yokomi K, Nakagawa T, Kaino T, Kawamukai M. Functional conservation of coenzyme Q biosynthetic genes among yeasts, plants, and humans. PLoS One. 2014;9:e99038.

Lenaz G. Membrane fluidity. In: Burton RM, Guerra FC, editors. Biomembranes. NATO ASI series (series a: life sciences), vol 76. Boston: Springer; 1984.

Niu Y, Xiang Y. An overview of biomembrane functions in plant responses to high-temperature stress. Front Plant Sci. 2018;9:915.

Falk S, Maxwell DP, Laudenbach DE, Huner NPA. Photosynthetic adjustment to temperature. In: Baker NR, editor. Photosynthesis and the environment. Advances in photosynthesis and respiration, vol. 5. Dordrecht: Springer; 1996.

Cheong KY, Firlar E, Ficaro L, Gorbunov MY, Kaelber JT, Falkowski PG. Saturation of thylakoid-associated fatty acids facilitates bioenergetic coupling in a marine diatom allowing for thermal acclimation. Glob Chang Biol. 2021;27:3133–44.

Ding Y, Virlouvet L, Liu N, Riethoven J-J, Fromm M, Avramova Z. Dehydration stress memory genes of Zea mays; comparison with Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Plant Biol. 2014;14:141.

Wang X, Huang J. Principles and techniques of plant physiological biochemical experiment. Beijing: Higher Education Press; 2015.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Xuebing Dai for his assistance in the cultivation of seedlings.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2019YFD100200); the Yunnan Provincial Innovation Team on Kapok Fiber Industrial Plantation (2018HC014); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31560207, 32060094, 31560093).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HM and YZ conceived and designed the research. ZX performed the experiments. YZ wrote the manuscript. JW made helpful comments on the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1

The maximum chlorophyll fluorescence (Fm) and ground fluorescence (Fo) in seedlings of Bombax ceiba subjected to dehydration and heat treatments.

Additional file 2

All the identified lipid species in leaves of Bombax ceiba. (DOCX 40 kb)

Additional file 3

The content of diacylglycerol (DAG) and triacylglycerol (TAG) in seedlings of Bombax ceiba subjected to dehydration and heat treatments.

Additional file 4

The double bond index (DBI)-acyl chain length (ACL) ratio of phospholipids in seedlings of Bombax ceiba subjected to heat treatments.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng, Y., Xia, Z., Wu, J. et al. Effects of repeated drought stress on the physiological characteristics and lipid metabolism of Bombax ceiba L. during subsequent drought and heat stresses. BMC Plant Biol 21, 467 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-021-03247-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-021-03247-4