Abstract

The human-pathogenic Enterobacter species are widely distributed in diverse environmental conditions, however, the understanding of the virulence factors and genetic variations within the genus is very limited. In this study, we performed comparative genomics analysis of 49 strains originated from diverse niches and belonged to eight Enterobacter species, in order to further understand the mechanism of adaption to the environment in Enterobacter. The results showed that they had an open pan-genome and high genomic diversity which allowed adaptation to distinctive ecological niches. We found the number of secretion systems was the highest among various virulence factors in these Enterobacter strains. Three types of T6SS gene clusters including T6SS-A, T6SS-B and T6SS-C were detected in most Enterobacter strains. T6SS-A and T6SS-B shared 13 specific core genes, but they had different gene structures, suggesting they probably have different biological functions. Notably, T6SS-C was restricted to E. cancerogenus. We detected a T6SS gene cluster, highly similar to T6SS-C (91.2%), in the remote related Citrobacter rodenitum, suggesting that this unique gene cluster was probably acquired by horizontal gene transfer. The genomes of Enterobacter strains possess high genetic diversity, limited number of conserved core genes, and multiple copies of T6SS gene clusters with differentiated structures, suggesting that the origins of T6SS were not by duplication instead by independent acquisition. These findings provide valuable information for better understanding of the functional features of Enterobacter species and their evolutionary relationships.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Enterobacter species are ubiquitous in nature and have been isolated from different ecological niches, such as plants, wastewater, human body and so on [1,2,3,4,5]. They exhibit considerable phenotypic and genomic diversities [6]. Enterobacter species are opportunistic pathogens and can cause infections in susceptible individuals, particularly those with compromised immune systems. Most studies on Enterobacter mainly focused on clinical diseases, such as nosocomial infection in humans, and suggested that it is a potential pathogenic bacteria [7], which can cause many kinds of human diseases [8]. Some Enterobacter strains show resistance to multiple antibiotics, posing a challenge for effective treatment [9]. Some Enterobacter strains are harmless commensals while some Enterobacter strains are potential pathogens, suggesting the complexity of Enterobacter species genomes and the need for further research to better understand their impact on human health. Protein secretion systems are critical for both pathogenic and nonpathogenic organisms to exploit nutrient resources within a host or specific niche and to evade recognition by the immune system [10, 11]. However, systematic analysis of protein secretion systems among Enterobacter species is very limited.

Several distinct protein secretion systems in bacterial pathogens are involved in invasion to their hosts [12]. So far, at least 6 types of secretion systems have been found in bacteria. Among these systems, Type VI secretion system (T6SS) has long been considered as a virulence factor of pathogenic bacteria. In addition to evading host immunity, T6SS is also associated with the competition for ecological niches and survival of bacteria under harmful environments [13]. Bacteria inject the effector proteins into the cells of intercellular competitors via T6SS to facilitate the inter-species bacterial competitions [14]. Therefore, T6SS represents crucial determinants of competitive fitness and pathogenic potential [15]. On the other hand, many beneficial bacteria utilize T6SS to promote plant growth by biofilm formation [16,17,18]. M Becker, S Patz, Y Becker, B Berger, M Drungowski, B Bunk, J Overmann, C Spröer, J Reetz and GV Tchuisseu Tchakounte [19] suggested that T6SS may provide endophytic bacteria advantages in environmental adaptability and host colonization. However, analysis of the distribution of T6SSs in Enterobacter species is very limited [20].

Comparative genomic analysis is a useful tool for exploring the evolution of species-specificity, it can provide evidence to better understand genomic rearrangement-related gene variations and deletions, horizontal gene transfer elements, and prophage-related sequence identification [21]. The increasing availability of whole genome sequences for bacteria enables the analysis of pan-genomes, encompassing core-, pan- and dispensable-genomes [22]. In addition, pan-genomics can be used for studying and modeling genomic diversity, evolution, adaptability, and population structure [23, 24]. Dispensable-genomes, which consists of genes shared by some but not all strains of a species, may also be involved in key activities of pathogenicity, drug resistance and stress response [23]. Although these dispensable genes may increase the adaptability of species to ecological niches, they are not necessary for their survival. Bacteria obtain some genes through horizontal gene transfer and these genes are often found in genome islands [25]. With the accumulation of bacterial genomes, comparative genomics is a better method to explore the phylogenetic relationship and the mechanism of environmental adaptation. To date, only few comparative genomics studies focusing exclusively on E. cloacae have been reported [20, 26,27,28]. There is no comparative genomics analysis involving multiple Enterobacter species. Here, we performed comparative analysis of eight Enterobacter species, including pan-genomics and the distribution of T6SS, in order to further understand the mechanism of adaption to the environment in Enterobacter.

Methods

Taxonomical evaluation by whole genome analysis

To ensure meaningful comparison between genomes and to analyze the genomic differences in different species, 49 representative Enterobacter strains belonging to eight Enterobacter species, each with complete genomes available in NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/), were selected based on completeness of genome sequences and diversity of habitats. The number of strains in each species ranged from 3 to 10. These strains were isolated from various habitats, including humans, plants, soils, wastewater, animals, and insects (Table 1). All genomes were uploaded and re-annotated on the Rapid Annotations using Subsystems Technology (RAST) server for SEED-based automated annotation and Clusters of orthologous Groups (COG) [29]. Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) search was performed with all predicted open reading frames (ORFs) from the 49 strains against Virulence Factor Database (VFDB) [30] to identify potential genes encoding known virulence factors, respectively.

Efficient Database framework for comparative Genome Analyses using BLAST score Ratios (EDGAR) was used for core genome, pan genome and singleton analysis, average amino acid identity (AAI) and average nucleotide identity (ANI) [31]. The cutoff values of AAI and ANI for species identification are 95% [32]. In order to clarify the phylogenetic classification of Enterobacter spp., two phylogenetic trees were constructed according to concatenated amino acid sequences of core genes and house-keeping genes, using FastTree 2.1.8 with 1,000 bootstrap iterations [33].

Pan- and core-genome analysis

The pan and core genome curves were performed by Bacterial Pan-Genome Analysis Pipeline (BPGA) [34]. The size of the pan-genome was speculated by a power law regression function Ps = κnγ using the BPGA pipeline. In this formula, if the exponent γ < 0, the pan-genome is closed and its size reaches a constant with addition of new sequencing genomes; if 0 < γ < 1, the pan-genome size is open and grows continuously [35].

Identification of genes involved in bacterial type VI secretion system

The core component clusters of Bacterial Type VI Secretion System (T6SS) were predicted by VRprofile [36]. Thirteen T6SS core components were selected for further analysis: COG3501 (vgrG), COG0542 (clpG), COG3520 (impH), COG3519 (impC), COG3518 (impF), COG3517 (iglB), COG3157 (hcp1), COG3516 (iglA), COG3515 (impA), COG3523 (icmF), COG3455 (dotU), COG3522 (impJ) and COG3521 (vasD) [37]. T6SS clusters with less than thirteen core component genes were discarded. In general, the T6SS gene clusters are categorized in three families (i-iii) and the family i is divided into six subfamilies (1, 2, 3, 4a, 4b and 5) [38,39,40,41]. To identify the T6SS subfamilies in higher precision, 31 well-studied T6SSs were selected to rebuild the phylogenetic tree based on the amino acid sequence of TssC (impC) protein. The phylogenetic tree was constructed with MEGA6.0 using the neighbor-joining method with 1,000 bootstrap test [42].

Results and discussion

General features of Enterobacter genomes

The genomes of many Enterobacter strains have been sequenced in the past few years. These genome sequences data constitute an excellent resource for evaluating the genetic diversity and exploring the evolutionary relationship in Enterobacter genus. In this study, we analyzed high quality genome sequences of 49 strains that were isolated from different environments including 25 from human, 12 from plant, 7 from soil, 3 from wastewater, 1 from animal, and 1 from insect, and representing eight species (Table 1). An overview of the basic properties of Enterobacter genomes was presented in Table 1. The genome size ranged from 4.43 MB (Enterobacter sp. SA187) to 5.6 MB (E. cloacae ATCC 13047), the GC contents varied from 54.38% to 56.1%, and the numbers of genes per genome ranged from 4027 to 5639. Interestingly, strains C126 and EA-1 had the much less protein-encoding genes (995 and 1052, respectively) but more pseudo genes (4332 and 4165, respectively). The big variations among these genomes suggested that the evolution of Enterobacter is accompanied by genomic adaptation to their different hosts and environments.

Genome sequence-based taxonomic classification of Enterobacter sp. strains

In this work, nine of the 49 strains were designated as Enterobacter sp. based on their 16S rRNA gene nucleic acid sequences, but were not assigned to a distinct species. To clarify the taxonomy of these strains, we calculated and compared the values of the average amino acid identity (AAI) and average nucleotide identity (ANI) of the 49 Enterobacter genomes. We found that Enterobacter sp. Crenshaw, Enterobacter sp. E20 and Enterobacter sp. HK169 showed identities of more than 98.8% with Enterobacter asburiae, while Enterobacter sp. ODB01 exhibited identities of 99.8% with Enterobacter kobei (Additional file 1). Therefore, we suggest assigning strains Crenshaw, E20, HK169 and ODB01 as E. asburiae Crenshaw, E. asburiae E20, E. asburiae HK169 and Enterobacter kobei ODB01.

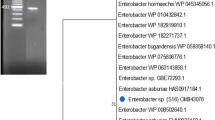

To confirm the updated classification of the 49 Enterobacter genomes, we employed phylogenetic analyses based on the concatenated amino acid sequences of core and house-keeping genes of the 49 Enterobacter genomes, of which the results showed that strains Crenshaw, E20 and HK169 were grouped with E. asburiae strains, while strain ODB01 was classified into the same clade containing E. kobei strains only (Fig. 1), consistent to the conclusions from AAI and ANI assays. Thus, our results suggested that genome sequence-based methodologies, such as AAI and ANI analyses, can be successfully applied for the taxonomic assignment of Enterobacter species.

Phylogenetic analysis based on concatenated amino acid sequence of different genes among 49 Enterobacter strains. A, phylogenetic tree based on 46 core genes; B, phylogenetic tree based on 65 house-keeping genes. Pane A shows the isolation resource of each species. The color of pane B and pane C indicate species and subspecies according to their average amino acid identity (AAI) and average nucleotide identity (ANI) values (Additional file 1)

Core- and pan-genome analyses reveal high genetic diversity of Enterobacter species

The core genome is essential to the basic lifestyle of bacteria, while the pan genome provides species diversity, environmental adaptability and other characteristics [23]. Pan-genomics analysis provides an efficient method for studying and modeling genomic diversity, evolution, adaptability, and population structures [43].To further evaluate the genetic diversity in Enterobacter genus, we performed core- and pan-genome analyses of the 49 genomes. The genomes of the 49 strains have 16,201 pan genes, 46 core genes and 169 singleton genes (Additional file 2), indicating that Enterobacter has high genetic diversity. In addition, core- and pan-genome ratio (RCP=core-genome/pan-genome) were calculated for each genome. Higher the RCP value indicates the smaller proportion of the mutated genes in the genomes. The genome of E. hormaechei had the lowest RCP value (0.03) and E. cancerogenus had the highest RCP value (0.75) (Additional file 2). These data demonstrated that E. hormaechei might be more genetically diversified than other Enterobacter species, while E. cancerogenus strains possessed more conserved genomes.

Core- and pan-genome ratio (RCP) can be used as an effective predictor for bacterial genetic diversity, but the value will change as increased number of genomes will change the size of pan-genome and core genome [44]. This is especially true for species with open pan-genomes, the size of which increases logarithmically as the number of genomes increased [45]. Compared with pan-genome analyses of other bacteria, such as Propionibacterium acnes (0.88) [46] and Erwinia amylovora (0.89) [47], the RCP value of Enterobacter is relatively low (0.003-0.75), which may be due to all analyses being based on the species level (Additional file 2). However, despite their diverse lifestyles, Enterobacter genomes still have an important set of core functions that reflect their adaptability to the environment and the metabolic strategies they preserve for survival.

For the sake of evaluating the genetic discrepancies among the 49 Enterobacter strains, we further calculated the number of specific genes of each strain by clustering a total of 215,761 coding sequences (CDS) across the genomes. In total, 6,633 specific genes were identified (Fig. 2A). The number of specific genes harbored by each strain varied in a broad range from 35 (E. asburiae L1) to 656 (Enterobacter sp. R4-368) (Fig. 2A), consistent to the variant principal genome features of the 49 strains (Table 1). Besides, we drew the fitting curves using the power-law regression model based on Heap’s Law with a fitted exponent γ = 0.35 to predict the development trends of the pan-genomes of Enterobacter genus and different Enterobacter species (Fig. 2B). Based on the patterns of the curves, the pan-genomes of both Enterobacter genus and different Enterobacter species were open (Fig. 2B and Additional file 3). The open pan-genome result showed that 49 analyzed strains only represent a subset of the genetic diversity of Enterobacter, indicating that the extensive genome is still evolving through gene acquisition and diversification. This result is consistent with previous studies on Enterococcus [20] and Enterobacter cloacae [48], demonstrating that the genes in Enterobacter constantly exchange within and between bacterial species. Although some features may be absorbed and integrated into the genome, only those features that have survival benefits to the organism will remain, while the rest will be discarded by highly active rearrangement events [20].

The Venn diagram and prediction of pan-genome in Enterobacter species. A Flower plots show the core gene number (in the center) and strain-specific gene number (in the petals) in Enterobacter strains. The numbers following the strain name represent the total number of coding proteins. B the pan- and core-genome size prediction using Bacterial Pan-Genome Analysis Pipeline (BPGA)

In order to find the differences of gene functions among Enterobacter species, gene annotation using the Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG) database were determined and compared. Our results showed that the pan-genome expanded in most categories with varying degrees compared to the core genome (Fig. 3). The largest expansion was detected in the group “replication, recombination and repair” with 1 ratio of 973. Functions of genes in this group are related to host-environment interactions, and may also be involved in niche adaptation, possibly acquired by mobile genetic elements [49]. In the categories “cell motility” and “inorganic ion transport and metabolism”, the pan gene numbers are 749 and 872 times more than that of core genes, respectively. Moreover, all genes involved in “cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis”, “defense mechanisms”, “coenzyme transport and metabolism”, “lipid transport and metabolism” are pan genes, suggesting these genes may contribute to their adaptation to diverse hosts or environmental conditions. In summary, the data obtained from the core- and pan-genome analyses revealed the high genetic diversity in Enterobacter species.

Expansion of the pan-genome compared with the core-genome for each functional category in Enterobacter species. All data in Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG) was normalized by min-max normalization. The number of core genes in each functional category was normalized (grey circle). The magnification of the pan gene number compared with that of core gene in each functional category is shown by the red circle. The COG categories with no circles contains only pan genes

Differences of secretion system gene clusters among Enterobacter strains

A total of 3,391 potential virulence factors were detected in the 49 Enterobacter strains, averaging 68 per genome (Fig. 4). These virulence factors were mainly involved in secretion system (1,873), iron acquisition (189), adhesion (184), fimbrial adherence determinants (140) and toxin (119). Protein secretion systems were the largest component of virulence factors, which are critical for both pathogenic and nonpathogenic organisms to exploit nutrient resources within a host or specific niche and to evade recognition by the immune system [50]. Interestingly, the distribution of the virulence factors exhibited obvious species-specific patterns. For example, protease mainly existed in E. ludwigii and E. cloacae, while nonfimbrial adherence determinants were mainly found in E. ludwigii., iron uptake system was primarily detected in E. cancerogenus and E. hormaechei, while fimbrial adherence determinants mainly existed in E. roggenkampii, E. hormaechei, E. kobei and E. cancerogenus.

The secretion of many important bacteria virulence factors is related to the secretion systems, including type VI secretion system (T6SS) [51]. T6SS participates in the pathogenicity of bacteria and is related to the formation of biofilm, recognition of competitor and stress responses and bacterial resistance acquisition [52, 53]. Based on the core components, we discovered three distinct types of T6SS gene clusters among the 49 strains, which were designated as T6SS-A, T6SS-B and T6SS-C (Fig. 5A). Additionally, based on the amino acid sequence of TssC protein, T6SS-A belonged to subtype i2, while T6SS-B and T6SS-C belonged to subtype i3 (Fig. 5B). Although T6SS-C is phylogenetically close to T6SS-B, no similarity in the core gene organization was found between T6SS-C and T6SS-B. The phylogenetic tree suggested that the different types of T6SS in Enterobacter were acquired by independent horizontal gene transfer [54].

Gene organization and phylogenetic relationships of type VI secretion system (T6SS) gene clusters in Enterobacter species. A Schematic representation of the identified T6SS genes in Enterobacter species. Three types of T6SS gene clusters were detected among the 49 strains, named T6SS-A, T6SS-B and T6SS-C. The Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG) IDs were presented under the genes in the clusters. B The phylogenetic trees was constructed using amino acid sequences of TssC in Enterobacter strains and 31 well-studied T6SSs (black). In general, T6SS gene clusters were classified into 3 groups (i-iii), and the group i was composed of six subfamilies (i1, i2, i3, i4a, i4b and i5). Our Enterobacter T6SSs were shown in red, pink and blue colors

Different numbers of secretion systems were identified in 49 strains. For example, no T6SS was detected in three strains including E. hormaechei C126, Enterobacter sp. 638, and Enterobacter sp. EA-1, one type of T6SS was found in 15 strains, and two types of T6SS were found in 31 strains. More than 93% of the strains harbored at least one functional T6SS and conserved in specific species, showing that T6SS was probably acquired from the common origin before the diversification of species within the genus [14]. The diverse Enterobacter T6SSs indicates the effect of selection pressures during the bacterial evolution and adaptation to the environments [55]. Interestingly, not only multiple T6SSs were present in one strain, but also the T6SS gene structures were different (Fig. 6), suggesting that these T6SS were not originated from duplication but by independent acquisition [37]. B Patricia, PA Luke, F Alain and AL Maria [56] suggested that several T6SS clusters in Pseudomonas putida were the result of duplication. However, Enterobacter strains with more than one T6SS normally contain clusters from different subfamilies or different gene structures within the same subfamily (Fig. 6), demonstrating the probability of horizontal gene transfer of T6SS [14, 54]. In addition, although multiple T6SSs are commonly found in most strains, no identical T6SSs in one or cross strains are found, demonstrating that different types of T6SSs involve in different biological function [55]. This differentiation indicates the different origins of T6SS and differences in functions and structures [57]. T6SS-A gene cluster was detected in 31 strains, T6SS-B was observed in 41 strains, suggesting its dominant presence. T6SS-C was restricted to E. cancerogenus strains (Fig. 6) with highly conserved gene cluster (>99% amino acid similarity), exhibiting significant species-specificity (Fig. 7A). Additionally, T6SS gene cluster in C. rodentium is almost identical to T6SS-C in E. cancerogenus (91.2% amino acid similarity) (Fig. 7A).

Gene organization of T6SS gene cluster in Enterobacter species. Heatmap shows the presence (black) or absence (grey) of T6SS gene cluster. T6SS cluster in composed of conseved T6SS core component genes (blue boxes) and variable genes. In each type, they have their own specific gene, such as outer membrane protein in T6SS-A, PAAR repeat protein with Rhs repeat (red color or purple color) or C-terminal toxin domain (red color or purple color with asterisk) in T6SS-B, chaperone-usher fimbrial biogenesis proteins in T6SS-C. T6SS: type VI secretion system

The icmF gene encodes frameshift mutations in different species. A the gene structure comparison of T6SS-C in three Enterobacter cancerogenus strains and T6SS gene cluster in Citrobacter rodentium ICC168. The percentage means the amino acid sequence identity. B Representation of the nucleotide sequences of five strains encoding icmF protein. The poly-A tract is shown in red. The codons and the translation result are shown, as well as those mutations produced from frameshifting are indicated (stop codon marked by the asterisks) with their corresponding size. C Prediction of the conserved domain of the PAAR domain-containing protein in T6SS-C

Gene structures of three types of T6SS were significantly different and therefore T6SS could be used as markers to distinguish strains (Fig. 6). For example, outer membrane protein existed in all T6SS-A gene clusters. One or more T6SS PAAR-repeat proteins were found in T6SS-B (a total of 77 proteins) (Additional file 4), which could be used as a marker to separate with other two T6SSs. Among these 77 proteins, only 26 proteins have an N-terminal PAAR motif and a C-terminal toxin domain, while others with an N-terminal PAAR motif and a RHS repeat (Additional file 4). We found an interesting element, a transcriptional slippery site (poly-A tract), in T6SS-C icmF genes (Fig. 7B), which might produce different protein mutations. However, this element was not detected in other two T6SS icmF genes. In T6SS-C, we also found chaperone-usher fimbrial biogenesis proteins (fimbrial protein, chaperone protein and outer membrane fimbrial usher porin), which were not found in other types. In addition, BLAST comparison of PAAR domain-containing protein gene in T6SS-C showed that this gene was only found in E. cancerogenus (MiY-F, CR-Eb1 and JY65) and C. rodentium (DBS100, ICC168) (Additional file 5), suggesting that T6SS-C was probably acquired from a common ancestor via an event of independent horizontal gene transfer. The presence of chaperone-usher fimbria proteins in T6SS-C was only reported in C. rodentium T6SS gene cluster, which might be involved in gastrointestinal colonization [58]. A poly-A tract was identified in the icmF gene of E. cancerogenus T6SS-C (Fig. 7B). The icmF (TssM) gene in C. rodentium and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis with the transcriptional slippery site (poly-A tract) (Fig. 7B) could lead to frameshifting and product two icmF variants and a full-length canonical protein [59], suggesting that these genes could produce three different proteins as transcriptional frameshifting in E. cancerogenus, which needs further experimental verification.

Rearrangement hotspot proteins (Rhs) proteins also played a primary determinant in intercellular competition [15]. Dickeya dadantii 3937 Rhs genes carried with C-terminal toxin domains deployed its function in intercellular inhibition [60].Further protein structure analysis of IcmF revealed a PAAR motif but different from the classical Rhs and without C-terminal toxin domain (Fig. 7C), suggesting that IcmF is a truncated protein lack of effective interspecies competition [60]. We also found four types of PAAR-domain containing proteins, and some of them are fused to Rhs proteins [61]. Here, we also found four types of this protein, including T6SS PAAR-repeat protein/Rhs protein, T6SS PAAR-repeat protein/actin-ADP-ribosylating toxin, T6SS PAAR-repeat protein and PAAR domain-containing protein (Fig. 6). J Ma, M Sun, W Dong, Z Pan, C Lu and H Yao [62] demonstrated that Rhs proteins with an N-terminal PAAR motif and a C-terminal toxin domain could promote colonization and fitness during infection.

Conclusion

In summary, analysis of 49 Enterobacter genomes demonstrated that their core- and pan-genome are open, and a number of virulence factors were characterized. Comparative genomic analysis revealed that the secretion systems are the largest among virulence factors, involved in the pathogenicity and niche adaptation. T6SS gene clusters were detected in most Enterobacter strains. The composition of the T6SS gene clusters varied, but its core components were found to be highly conserved. A total of three different types of T6SS were detected by comparative genomics. T6SS-A, and T6SS-B were widely distributed in Enterobacter species. A novel type of T6SS, named T6SS-C, was only detected in in E. cancerogenus. Whilst this type of T6SS gene cluster is not available in other Enterobacter species, the same type of T6SS was detected in the remotely related genus Citrobacter, suggesting that T6SS was probably acquired by an event of horizontal gene transfer. It is likely that the different types of T6SSs are involved in different biological functions and contribute to the evolutional adaptation.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Andreozzi A, Prieto P, Mercado-Blanco J, Monaco S, Zampieri E, Romano S, Valè G, Defez R, Bianco C. Efficient colonization of the endophytes Herbaspirillum huttiense RCA24 and Enterobacter cloacae RCA25 influences the physiological parameters of Oryza sativa L. cv. Baldo rice. Environ Microbiol. 2019;21(9):3489–504.

Andrés-Barrao C, Lafi FF, Alam I, De Zélicourt A, Eida AA, Bokhari A, Alzubaidy H, Bajic VB, Hirt H, Saad MM. Complete genome sequence analysis of Enterobacter sp. SA187, a plant multi-stress tolerance promoting endophytic bacterium. Front Microbiol. 2023;2017:8.

Chung Jh, Jeong H, Ryu CM. Complete Genome Sequences of Enterobacter cancerogenus CR-Eb1 and Enterococcus sp. Strain CR-Ec1, Isolated from the Larval Gut of the Greater Wax Moth Galleria mellonella. Genome Announcements. 2018;6(7):e00044–00018.

Coulson TJ, Patten CL. Complete genome sequence of Enterobacter cloacae UW5, a rhizobacterium capable of high levels of indole-3-acetic acid production. Genome Announcements. 2015;3(4):e00843–00815.

Diab A, Ageez A, Sami S. Enterobacter cloacae MSA4, a new strain isolated from the rhizosphere of a desert plant, produced potent biosurfactant used for enhancing the biodegradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) during the bioremediation of spent motor oil-polluted sandy soil. Int J Sci Res. 2017;6:2726–34.

Paauw A, Caspers MP, Schuren FH, Leverstein-van Hall MA, Deletoile A, Montijn RC, Verhoef J, Fluit AC. Genomic diversity within the Enterobacter cloacae complex. PLoS One. 2008;3(8):e3018.

Demir T, Baran G, Buyukguclu T, Sezgin FM, Kaymaz H. Pneumonia due to Enterobacter cancerogenus infection. Folia Microbiologica. 2014;59(6):527–30.

Garazzino S, Aprato A, Maiello A, Massé A, Biasibetti A, De Rosa FG, Di Perri G. Osteomyelitis caused by Enterobacter cancerogenus infection following a traumatic injury: case report and review of the literature. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(3):1459–61.

Jiménez-Castillo RA, Aguilar-Rivera LR, Carrizales-Sepúlveda EF, Gómez-Quiroz RA, Llantada-López AR, González-Aguirre JE, Náñez-Terreros H, Rendón-Ramírez EJ. A case of round pneumonia due to Enterobacter hormaechei: the need for a standardized diagnosis and treatment approach in adults. Revista do Instituto de Medicina Tropical de São Paulo. 2021;63:e3.

Green ER, Mecsas J. Bacterial secretion systems: an overview. Microbiol Spectrum. 2016;4(1):4.1.13.

Soria-Bustos J, Ares MA, Gómez-Aldapa CA, González-y-Merchand JA, Girón JA, De la Cruz MA. Two type VI secretion systems of Enterobacter cloacae are required for bacterial competition, cell adherence, and intestinal colonization. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:560488.

Ribet D, Cossart P. How bacterial pathogens colonize their hosts and invade deeper tissues. Microbes Infect. 2015;17(3):173–83.

Wang T, Si M, Song Y, Zhu W, Gao F, Wang Y, Zhang L, Zhang W, Wei G, Luo Z-Q. Type VI secretion system transports Zn2+ to combat multiple stresses and host immunity. PLoS Pathogens. 2015;11(7):e1005020.

Bernal P, Llamas MA, Filloux A. Type VI secretion systems in plant-associated bacteria. Environ Microbiol. 2018;20:1–15.

Alcoforado Diniz J, Coulthurst SJ. Intraspecies Competition in Serratia marcescens Is Mediated by Type VI-Secreted Rhs Effectors and a Conserved Effector-Associated Accessory Protein. J Bacteriol. 2015;197(14):2350–60.

Bernal P, Allsopp LP, Filloux A, Llamas MA. The Pseudomonas putida T6SS is a plant warden against phytopathogens. Isme J. 2017;11(4):972–87.

Gallique M, Decoin V, Barbey C, Rosay T, Merieau A. Contribution of the Pseudomonas fluorescens MFE01 type VI secretion system to biofilm formation. Plos One. 2017;12(1):e0170770.

Lin J, Zhang W, Cheng J, Yang X, Zhu K, Wang Y, Wei G, Qian PY, Luo ZQ, Shen X. A Pseudomonas T6SS effector recruits PQS-containing outer membrane vesicles for iron acquisition. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14888.

Becker M, Patz S, Becker Y, Berger B, Drungowski M, Bunk B, Overmann J, Spröer C, Reetz J, Tchuisseu Tchakounte GV. Comparative genomics reveal a flagellar system, a type VI secretion system and plant growth-promoting gene clusters unique to the endophytic bacterium Kosakonia radicincitans. Front Microbiol. 1997;2018:9.

Liu WY, Wong CF, Chung KMK, Jiang JW, Leung FCC. Comparative genome analysis of Enterobacter cloacae. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e74487.

Land M, Hauser L, Jun SR, Nookaew I, Leuze MR, Ahn TH, Karpinets T, Lund O, Kora G, Wassenaar T, et al. Insights from 20 years of bacterial genome sequencing. Funct Integr Genomics. 2015;15(2):141–61.

Bhatti A, Shah FS, Azhar J, Ahmad S, John P. Pan-transcriptomics and its applications. In: Pan-genomics. Applications, Challenges, and Future Prospects. London: Academic Press; 2020. p. 343–56.

Vernikos G, Medini D, Riley DR, Tettelin H. Ten years of pan-genome analyses. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2015;23:148–54.

Iranzadeh A, Mulder NJ. Bacterial Pan-Genomics. In: Microbial Genomics in Sustainable Agroecosystems. New York: Springer; 2019. p. 21–38.

Syvanen M. Evolutionary implications of horizontal gene transfer. Ann Rev Genet. 2012;46:341–58.

Senchyna F, Tamburini FB, Murugesan K, Watz N, Bhatt AS, Banaei N. Comparative genomics of Enterobacter cloacae complex before and after acquired clinical resistance to Ceftazidime-Avibactam. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2021;101(4):115511.

Xia Y, Xu Y, Zhou Y, Yu Y, Chen Y, Li C, Xia W, Tao J. Comparative genome analyses uncovered the cadmium resistance mechanism of enterobacter cloacae. Int Microbiol. 2023;26(1):99–108.

Mustafa A, Ibrahim M, Rasheed MA, Kanwal S, Hussain A, Sami A, Ahmed R, Bo Z. Genome-wide Analysis of Four Enterobacter cloacae complex type strains: Insights into Virulence and Niche Adaptation. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):8150.

Aziz RK, Bartels D, Best AA, DeJongh M, Disz T, Edwards RA, Formsma K, Gerdes S, Glass EM, Kubal M. The RAST Server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics. 2008;9(1):1–15.

Chen L, Yang J, Yu J, Yao Z, Sun L, Shen Y, Jin Q. VFDB: a reference database for bacterial virulence factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:325–8.

Blom J, Albaum SP, Doppmeier D, Pühler A, Vorhölter F-J, Zakrzewski M, Goesmann A. EDGAR: a software framework for the comparative analysis of prokaryotic genomes. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10(1):154.

Thompson CC, Chimetto L, Edwards RA, Swings J, Stackebrandt E, Thompson FL. Microbial genomic taxonomy. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:913.

Price MN, Dehal PS, Arkin AP. FastTree 2-approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PloS One. 2010;5:e9490.

Chaudhari NM, Gupta VK, Dutta C. BPGA-an ultra-fast pan-genome analysis pipeline. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):1–10.

Tettelin H, Riley D, Cattuto C, Medini D. Comparative genomics: the bacterial pan-genome. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2008;11(5):472–7.

Li J, Tai C, Deng Z, Zhong W, He Y, Ou H-Y. VRprofile: gene-cluster-detection-based profiling of virulence and antibiotic resistance traits encoded within genome sequences of pathogenic bacteria. Brief Bioinformatics. 2018;19(4):566–74.

Boyer F, Fichant G, Berthod J, Vandenbrouck Y, Attree I. Dissecting the bacterial type VI secretion system by a genome wide in silico analysis: what can be learned from available microbial genomic resources? BMC Genomics. 2009;10(1):104.

Barret M, Egan F, Fargier E, Morrissey JP, O’Gara F. Genomic analysis of the type VI secretion systems in Pseudomonas spp.: novel clusters and putative effectors uncovered. Microbiology. 2011;157(6):1726–39.

Russell AB, Wexler AG, Harding BN, Whitney JC, Bohn AJ, Goo YA, Tran BQ, Barry NA, Zheng H, Peterson SB. A type VI secretion-related pathway in Bacteroidetes mediates interbacterial antagonism. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;16(2):227–36.

Li J, Yao Y, Xu HH, Hao L, Deng Z, Rajakumar K, Ou HY. SecReT6: a web-based resource for type VI secretion systems found in bacteria. Environ Microbiol. 2015;17(7):2196–202.

Barret M, Egan F, O’Gara F. Distribution and diversity of bacterial secretion systems across metagenomic datasets. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2013;5(1):117–26.

Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30(12):2725–9.

Iranzadeh A, Mulder NJ. Bacterial pan-genomics. Microb Genomics Sustain Agroecosyst. 2019;1:21–38.

Ghatak S, Blom J, Das S, Sanjukta R, Puro K, Mawlong M, Shakuntala I, Sen A, Goesmann A, Kumar A. Pan-genome analysis of Aeromonas hydrophila, Aeromonas veronii and Aeromonas caviae indicates phylogenomic diversity and greater pathogenic potential for Aeromonas hydrophila. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2016;109(7):945–56.

Muzzi A, Masignani V, Rappuoli R. The pan-genome: towards a knowledge-based discovery of novel targets for vaccines and antibacterials. Drug Discov Today. 2007;12(11–12):429–39.

Tomida S, Nguyen L, Chiu B-H, Liu J, Sodergren E, Weinstock GM, Li H. Pan-genome and comparative genome analyses of Propionibacterium acnes reveal its genomic diversity in the healthy and diseased human skin microbiome. mBio. 2013;4(3):e00003–00013.

Mann RA, Smits TH, Bühlmann A, Blom J, Goesmann A, Frey JE, Plummer KM, Beer SV, Luck J, Duffy B. Comparative genomics of 12 strains of Erwinia amylovora identifies a pan-genome with a large conserved core. PloS One. 2013;8(2):e55644.

Zhong Z, Zhang W, Song Y, Liu W, Xu H, Xi X, Menghe B, Zhang H, Sun Z. Comparative genomic analysis of the genus Enterococcus. Microbiol Res. 2017;196:95–105.

Chan JP, Wright JR, Wong HT, Ardasheva A, Brumbaugh J, McLimans C, Lamendella R. Using bacterial transcriptomics to investigate targets of host-bacterial interactions in Caenorhabditis elegans. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1–12.

Green ER, Mecsas J. Bacterial secretion systems: an overview. Microbiol Spectr. 2016;4(1):213–39.

Cai H, Yu J, Qiao Y, Ma Y, Zheng J, Lin M, Yan Q, Huang L. Effect of the type VI secretion system secreted protein hcp on the virulence of aeromonas salmonicida. Microorganisms. 2022;10(12):2307.

Song H, Kang Y, Qian A, Shan X, Li Y, Zhang L, Zhang H, Sun W. Inactivation of the T6SS inner membrane protein DotU results in severe attenuation and decreased pathogenicity of Aeromonas veronii TH0426. BMC Microbiol. 2020;20:1–11.

Navarro-Garcia F, Ruiz-Perez F, Cataldi AA, Larzabal M. Type VI secretion system in pathogenic escherichia coli: structure, role in virulence and acquisition. Front Microbiol. 1965;2019:10.

Sun J, Su H, Zhang W, Luo X, Li R, Liu M. Comparative genomics revealed that Vibrio furnissii and Vibrio fluvialis have mutations in genes related to T6SS1 and T6SS2. Arch Microbiol. 2023;205(5):207.

Bao H, Zhao J, Zhu S, Wang S, Zhang J, Wang X-Y, Hua B, Liu C, Liu H, Liu S-L. Genetic diversity and evolutionary features of type VI secretion systems in Salmonella. Future Microbiol. 2019;14(02):139–54.

Patricia B, Luke PA, Alain F, Maria AL. The Pseudomonas putida T6SS is a plant warden against phytopathogens. ISME J. 2017;11:972–87.

Shyntum DY, Venter SN, Moleleki LN, Toth I, Coutinho TA. Comparative genomics of type VI secretion systems in strains of Pantoea ananatis from different environments. BMC Genomics. 2014;15(1):163.

Petty NK, Bulgin R, Crepin VF, Cerdeo-Tárraga AM, Thomson NR. The Citrobacter rodentium Genome Sequence Reveals Convergent Evolution with Human Pathogenic Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2009;192(2):525–38.

Gueguen E, Wills NM, Atkins JF, Cascales E. Transcriptional frameshifting rescues Citrobacter rodentium type VI secretion by the production of two length variants from the prematurely interrupted tssM gene. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:1004869.

Koskiniemi S, Lamoureux JG, Nikolakakis KC, T"Kint dR, C., Kaplan MD, Low DA, Hayes CS: Rhs proteins from diverse bacteria mediate intercellular competition. Proc National Acad ences USA. 2013, 110(17):7032-7037.

Shneider MM, Buth SA, Ho BT, Basler M, Mekalanos JJ, Leiman PG. PAAR-repeat proteins sharpen and diversify the type VI secretion system spike. Nature. 2013;500(7462):350.

Ma J, Sun M, Dong W, Pan Z, Lu C, Yao H. PAAR-Rhs proteins harbor various C-terminal toxins to diversify the antibacterial pathways of type VI secretion systems. Environ Microbiol. 2017;19(1):345–60.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32200094), Hubei Key Laboratory of Biological Resources Protection and Utilization (Hubei Minzu University) (No. PT012201), the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province (2022CFB674).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MP and ZW wrote the main manuscript text and WL, ZJ, FZ prepared figures and tables. AZ revised the main manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Similarity identity matrix of average amino acid identity (AAI) (upper triangle) and average nucleotide identity (ANI) (lower triangle) among Enterobacter species. The color represents the numerical size, red color means the highest value, green color represents the lowest value.Strains are considered one species when share >95% AAI and ANI.

Additional file 2.

Pan-genome features in different Enterobacter species.

Additional file 3.

Pan-genome, core-genome and singleton development of different Enterobacter species.

Additional file 4.

Prediction of conserved domain in T6SS PAAR-repeat proteins (only list the protein with N-terminal PAAR motif and a C-terminal toxin domain).

Additional file 5.

BLAST comparison and taxonomic analysis based on PAAR domain-containing protein in T6SS-C gene cluster. The phylogenetic tree is inferred using the Neighbor-Joining method.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Peng, M., Lin, W., Zhou, A. et al. High genetic diversity and different type VI secretion systems in Enterobacter species revealed by comparative genomics analysis. BMC Microbiol 24, 26 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-023-03164-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-023-03164-6