Abstract

Background

Staphylococcus shinii appears as an umbrella species encompassing several strains of Staphylococcus pseudoxylosus and Staphylococcus xylosus. Given its phylogenetic closeness to S. xylosus, S. shinii can be found in similar ecological niches, including the microbiota of fermented meats where the species may contribute to colour and flavour development. In addition to these conventional functionalities, a biopreservation potential based on the production of antagonistic compounds may be available. Such potential, however, remains largely unexplored in contrast to the large body of research that is available on the biopreservative properties of lactic acid bacteria. The present study outlines the exploration of the genetic basis of competitiveness and antimicrobial activity of a fermented meat isolate, S. shinii IMDO-S216. To this end, its genome was sequenced, de novo assembled, and annotated.

Results

The genome contained a single circular chromosome and eight plasmid replicons. Focus of the genomic exploration was on secondary metabolite biosynthetic gene clusters coding for ribosomally synthesized and posttranslationally modified peptides. One complete cluster was coding for a bacteriocin, namely lactococcin 972; the genes coding for the pre-bacteriocin, the ATP-binding cassette transporter, and the immunity protein were also identified. Five other complete clusters were identified, possibly functioning as competitiveness factors. These clusters were found to be involved in various responses such as membrane fluidity, iron intake from the medium, a quorum sensing system, and decreased sensitivity to antimicrobial peptides and competing microorganisms. The presence of these clusters was equally studied among a selection of multiple Staphylococcus species to assess their prevalence in closely-related organisms.

Conclusions

Such factors possibly translate in an improved adaptation and competitiveness of S. shinii IMDO-S216 which are, in turn, likely to improve its fitness in a fermented meat matrix.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Staphylococcus shinii has recently been described and validated as a novel species [1, 2]. The National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) has meanwhile listed 16 genomes belonging to this species (Genome database; accessed May 2024), including that of the reference strain, S. shinii K22-5 M. Ten of these strains were reclassified from other staphylococcal species into S. shinii, including S. pseudoxylosus 14AME19 isolated from Korean fermented bean paste [3], S. xylosus INIFAP 005–08 and INIFAP 004–15, both isolated from cattle parasites [4], S. xylosus CHJ_154 isolated from raw cow’s milk, S. xylosus LSR_02N isolated from river water, and S. xylosus SNUC 416, SNUC 4611, SNUC 4554, SNUC 3812, and SNUC 4555 from a bovine mastitis collection [5]. Five other strains obtained from Korean fermented bean paste and human nasal swabs were annotated directly as S. shinii (BG1-2, BG2-4, KG4-6, KG4-7, and NNS4w).

Staphylococcus shinii thus bears a close genetic resemblance to both S. xylosus and S. pseudoxylosus, the latter also being a relatively novel species isolated first from bovine mastitis samples [6]. Both the taxonomic closeness and the sharing of similar ecological niches imply that the metabolic and functional information available for S. xylosus can serve as a benchmark to explore the relevance of this new and yet poorly described S. shinii species for food technology purposes. Staphylococcus xylosus belongs to the coagulase-negative staphylococci (CNS), situated within the group of Gram-positive, catalase-positive cocci (GCC) [7]. Ever since its first isolation from human skin [8], this ubiquitous species has been recovered from a wide range of environments. Although the species is commonly found among the normal mammalian skin microbiota [9], it can also act as an opportunistic pathogen leading to skin pathologies in both animals [10] and humans [11]. As such, it has been isolated from human clinical material and hospital environments [12]. Due to its association with mammalian skin, S. xylosus is a common member of the natural microbiota of meat and various products derived thereof. This is especially the case for cured meats, such as fermented meat products, where it is selected for because of its high salt tolerance [13,14,15].

In fermented meat products, S. xylosus can either arise spontaneously as a member of the natural meat microbiota, favoured by the fermentation conditions, or can deliberately be added as a starter culture, usually in combination with an acidifying lactic acid bacterium [16, 17]. The practice of using S. xylosus as a starter culture is based on the microorganism’s ability to contribute to the fermented meat colour and flavour, its capacity to limit oxidation of free fatty acids and avoid rancidity, and its adaptation to the fermented meat matrix and the stress conditions imposed thereon during processing [9, 18]. In addition to these conventional functionalities, there seems to be a potential for some strains within the GCC group to contribute to food safety based on the production of antagonistic compounds, i.e., microbial products that limit or inhibit bacterial growth of competing species or strains [19,20,21].

In the past, strategies that looked into starter culture use for biopreservation have mostly focused on lactic acid bacteria [22, 23], whereas information about the production of antagonistic compounds by GCC strains is scarce [24]. A screening of more than 300 GCC strains indicated that such activity is likely uncommon among GCC, as only a small minority of positive strains was found [20]. One of these few positive strains, S. shinii IMDO-S216, formerly classified as S. xylosus IMDO-S216, displayed antibacterial activity against a range of other GCC when studied through a deferred antagonism test. Another study has described the partial purification of a bacteriocin-like peptide produced by a S. xylosus strain and tested its inhibitory activity against other bacteria as well as its resistance to temperature and enzymatic digestion [25]. These findings, although interesting, remain of a preliminary nature in the absence of further characterization and identification. Therefore, further phenotypic and genomic explorations are needed to shed light on the identity and regulation of such antagonistic compounds within S. shinii metabolism. To the best of our knowledge, such research is currently not available for this species, partly due to its novelty. In the past, a genome analysis has been performed to elucidate the adaptation mechanisms that create fitness for S. xylosus within a meat matrix, linking it to the use of energy sources and other biological responses, but without reporting on the presence of antagonistic compounds [9]. Other characteristics of S. xylosus that have been elucidated through genome analysis include the presence of adhesion and biofilm related genes [26] and an increased oxidative stress resistance [9]. These abilities enhance competitiveness and offer an advantage for starter cultures that may contribute to overruling the autochthonous microbiota in a fermentative environment, and could be potentially shared by the new S. shinii species.

Competitiveness factors, among which antimicrobial activities against competitors can be counted [27], can be defined as the dynamic mechanisms that help bacteria respond to the challenges and fluctuations of the environment that affect their fitness [28]. For S. xylosus, inhibitory activity against strains of Listeria and Pseudomonas, as well as the release of an uncharacterized molecule that can inhibit the formation of Staphylococcus aureus biofilms, have been shown as promising examples of competitiveness factors with bioprotective impact [29, 30]. However, a more in-depth phenotypical and genomic exploration of the new species is needed to be able to fully benefit from this untapped potential.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to get a deeper insight into the antagonistic compounds and competitiveness factors available within the genome of S. shinii IMDO-S216, as to better understand how this strain functions within fermented meat ecosystems.

Methods

Bacterial strain, media, and inoculum build-up

The S. shinii IMDO-S216 strain used in this study, formerly classified as S. xylosus IMDO-S216, originated from the culture collection of the Research Group of Industrial Microbiology and Food Biotechnology (Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Brussels, Belgium). The strain was stored at -80 °C in glycerol-containing (25% v/v) brain heart infusion (BHI) medium (Oxoid, Basingstoke, Hampshire, United Kingdom). The inoculum build-up was performed as previously described [31]. Briefly, the strain was propagated twice in 10 mL of BHI media and incubated at 30 °C for 12 h. The precultures were then transferred (1% v/v) into 10 mL of BHI for a final incubation at 30 °C for 12 h.

DNA extraction for Illumina and ONT library preparation

DNA extraction was performed as previously detailed, with some adaptations [32]. Different volumes of culture (3, 5, 10, and 25 mL) were tested to assess the optimal starting volume. A bacterial cell pellet was obtained from the centrifugation of 25 mL of BHI culture at 5,000 x g for 10 min at 4 °C. Genomic DNA was extracted from this pellet using the Genomic-tip 20/G kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) with minor modifications. The bacterial pellet was resuspended in 1 mL of buffer B1 [with 2 µL of Rnase A added (100 mg/mL)] to which 40 µL of both a lysozyme solution (100 mg/mL; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and a mutanolysin solution (12.5 kU/mL; MilliporeSigma, Burlington, Massachusetts, United States of America), and 250 µL of a Qiagen proteinase K stock solution were added, followed by an incubation of 45 min at 37 °C. Deproteinization was achieved by adding 350 mL of buffer B2 to the lysate with a second incubation period of 30 min at 50 °C. The Genomic-tip 20/G column was equilibrated with 1 mL of buffer QBT and allowed to empty by gravitational flow. The prepared sample was then vortexed for 10 s at maximum speed and applied to the equilibrated column, where a combination of gravitational flow and gentle positive pressure using a disposable syringe was applied to assist the flow. The process was followed by threefold washing of the column with 1 mL of buffer QC each to remove as many contaminants as possible. The genomic DNA was eluted in 2 mL of buffer QF and precipitated with 1.4 mL of isopropanol. The precipitated DNA was recovered by inverting the tube and picked using a pipette tip, and then transferred to a tube containing 100 µL of nuclease-free water. The concentration of the extracted genomic DNA was measured with a Qubit fluorometer using the double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) high-sensitivity (HS) assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, United States of America). The DNA purity was assessed with a NanoDrop ND-2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Based on the concentrations and the ratio of absorbance at 260/280 nm obtained, the optimal culture volume was selected.

DNA sequencing

A combination of long-read and short-read sequencing of the genomic DNA was performed as previously detailed, with some adaptations [32]. Long reads were generated using the Oxford Nanopore Technologies’ (ONT) MinION sequencing device (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford, United Kingdom) [33]. Two µg of high-molecular-mass DNA were used as input for the ONT library preparation using the ONT ligation sequencing kit (SQK-LSK109; Oxford Nanopore Technologies), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After loading the final library into an R9.4.1 flow cell, the sequencing run was performed on a MinION MK1b device using the MinKNOW software for data acquisition. Basecalling and barcode separation were performed with Guppy (v4.4.2) using the configuration file dna_r9.4.1_450bps_flipflop.cfg in high-accuracy GPU-accelerated mode (Oxford Nanopore Technologies). Quality check and trimming were performed using the NanoPack package (v1.1.0) [34]. First, NanoQC and NanoPlot were used for quality checking, whereupon NanoFilt was used to trim non-representative read ends and filter out low-quality reads, by applying the following parameters: q, 12 (filtering out reads with a Q-score lower than 12); headcrop, 80; and tailcrop, 60 (the two latter parameters allow trimming a certain number of nucleotides from the beginning and end of each read to avoid a biased content of nucleotide distribution and lower sequencing quality). Short-read sequencing was performed on an Illumina NovaSeq sequencing system (250 bp paired-end) (Illumina, San Diego, CA, United States of America) by the VUB/ULB BRIGHTcore sequencing core facility (Jette, Belgium). Quality check and trimming were performed with the tools FastQC (v0.11.3) [35] and Trimmomatic (v0.36) [36], with the following parameters: headcrop, 10 (trimming of 10 nucleotides from the beginning of each read); leading, 30 (trimmed bases off at the start of a read if below the specified threshold quality); trailing, 30 (trimmed bases off at the end of a read if below the specified threshold quality); slidingwindow, 4:15 (performed a sliding-window trimming, cutting off the read if the average quality of the bases in the window fell below the threshold specified); and minlen, 20 (reads under the specified length were not considered).

Whole-genome de novo assembly

The quality-assessed and trimmed long- and short-reads were used to generate a hybrid assembly by using Unicycler (v0.5.0) [37]. The assembler was used in three different modes – Conservative, Normal, and Bold – and the results were visualized using Bandage [38] to compare the architecture of the assemblies, to check circularity/linearity, and to give an estimation of copy numbers of the plasmids. A pairwise comparison of the contigs generated with each of the three modes was performed using the basic local alignment search tool for nucleotides (blastn) [39, 40] to identify which contigs had been resolved due to more constrictive modes. The Public Database for Molecular Typing and Microbial Genome Diversity (PubMLST) was used to elucidate the types of replicons of the resolved plasmids by performing a plasmid multilocus sequence typing (pMLST; accessed May 2024) [41].

Genome analysis of biosynthetic gene clusters related to antagonistic compounds and competitiveness factors

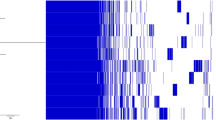

The genome assembly was annotated with Prokka (v1.14.6) [42]. Next, the bacterial version of the tool antiSMASH (antibiotics and Secondary Metabolites Analysis Shell; v6.0) [43] was used to mine the genome data for secondary metabolite biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs), applying a profile hidden Markov models-based approach. To do so, the detection strictness was set to ‘relaxed’. Analysis of protein sequences with the blastp algorithm [39] was performed on the antiSMASH output to designate and/or confirm the functions predicted. The BGCs were compared with the widely studied S. aureus subsp. aureus NCTC 8325 strain (BioProject accession number PRJNA57795). In addition, a comparative analysis focusing on the detected BGCs was performed with selected microorganisms from the Staphylococcus genus according to the following criteria: Staphylococcus xylosus strains with a complete or chromosome assembly level; Staphylococcus shinii strains with a complete or chromosome assembly level; other Staphylococcus species found in fermented meat matrices with a complete or chromosome assembly level; and other Staphylococcus species found in other fermented food matrices with a complete or chromosome assembly level (Table 1). As such, 16 strains of S. xylosus were selected; out of non-xylosus species, eight Staphylococcus carnosus, two Staphylococcus condimenti, four Staphylococcus equorum, one Staphylococcus hominis, three Staphylococcus nepalensis, one Staphylococcus pasteuri, one Staphylococcus shinii (formerly classified as Staphylococcus pseudoxylosus), one Staphylococcus succinus, and one Staphylococcus warneri strain(s) were selected. Except for S. xylosus TCD16 and S. xylosus ATCC 29,971, with a chromosome assembly level, all strains selected displayed a complete assembly level. Out of the 38 strains, 14 were isolated from fermented sausages, nine of them being S. xylosus isolates. Other fermented sources of isolation were fish sauce, soy sauce mash, shrimp paste, kimchi, and soybeans. Staphylococcus xylosus strains with a complete or chromosome assembly level were also isolated from animal faecal matter, mouse rectum, leafy vegetable, milker’s hands and, in less detail, human skin. By the time of the selection of these organisms for a comparative analysis, out of the 16 S. shinii present in the NCBI Genome database, only S. shinii 14AME19 presented a complete assembly level. The other candidate strains, even if they were ecologically relevant due to their sourcing from fermented soybeans, bovine mastitis samples, or raw cow’s milk, only presented contig or scaffold assembly level, and were therefore not selected. The genomes were retrieved from the Genome database of the NCBI (accessed March 2024). The amino acid sequences of the BGCs of interest of S. shinii IMDO-S216 were aligned against the nucleotide sequences of the microorganisms selected using the tblastn algorithm [44]. A summarized comparison with the hypothesized presence or absence of the BGCs is displayed in Fig. 1. Two sequences were considered as homologous if their alignment had a minimum sequence identity of 30% and a query coverage of at least 70% [45]. The percentage identity and query coverage of each gene were individually inferred and their probable presence or absence was indicated through a colour code based on the previously mentioned criteria (Table S1).

Overview of the presence or absence of the biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) present in Staphylococcus shinii IMDO-S216 in the bacterial genomes selected for comparative genomics analysis (Table 1). Green boxes: presence of all genes of the BGC. Orange boxes: one or more genes of the BGC are absent. The criteria applied to consider two sequences as homologous are a minimum of 30% sequence identity and a query coverage of at least 70%; the query coverage and percentage identity values for each gene are presented in Table S1

In parallel, a manual blastp analysis was performed, in which the protein database UniProt [55] was used to retrieve a compilation of the amino acid sequences from the order Bacillales and compared with those of S. shinii IMDO-S216 predicted by Prokka. The Conserved Domains Database webportal (CDD) [56] was used to visualize the proteins’ conserved regions. The PredictProtein server [57] was used to get an in-depth look at the structure and function of the proteins of interest. Screening for virulence factors (VFs) was performed through the online platform Vfanalyzer [58] of the Virulence Factor Database (VFDB) under default settings. BAGEL4 [59] was used to detect gene clusters related to bacteriocins and ribosomally synthesized and posttranslationally modified peptides (RiPPs). A summary of the bioinformatic tools used for each genomic cluster discovered is detailed in Table 2. The Artemis tool (v18.2.0) [60] was used to assess the genomic context of each sequence of interest.

Illustrations

Gene clusters were represented using the packages ggplot2 (v3.4.1) [61] and gggenes (v0.4.1) [62] in Rstudio (v4.2.2) [63], and biosynthetic pathways were plotted with the use of Inkscape (v1.1.2) [64].

Results

General features of the de novo-assembled genome of Staphylococcus shinii IMDO-S216

The ONT and Illumina sequence read sets contained 117,011 reads with on average 587× coverage and 5,590,125 reads with on average 496× coverage, respectively. The output of the Unicycler assembler in Normal resolution mode was manually curated using the output from Unicycler’s Bold resolution mode, resulting in the Staphylococcus shinii IMDO-S216 genome containing nine contigs, i.e., a single circular chromosome of 3.01 Mb and eight plasmid replicons (Table 3). Plasmids pIMDO_S216_8 and pIMDO_S216_9 displayed identical size but pairwise comparison showed 93.80% sequence identity. Also, plasmid pIMDO_S216_9 contained the lincomycin resistance protein (linA) and replication protein (rep) genes, as well as the quaternary ammonium compound-resistance protein (qacG) and replication protein (rep94) genes, whereas plasmid pIMDO_S216_8 did not.

To explain the presence of several plasmids in a strain, the incompatibility or ‘Inc typing’ system was used, which classifies plasmids by their ability to coexist in a stable manner within the same bacterial strain; this trait is dependent on the strain’s replication machinery. When two co-resident plasmids share the same Inc typing, they use the strain’s same replication mechanisms and are deemed incompatible [65]. The only plasmids found to share typings in the studied strain were pIMDO-S216-1 and pIMDO-S216-8, both typed as IncA/C. The element pIMDO-S216-2 was typed as vapBC, mainly described in literature as part of a toxin-antitoxin system in Shigella flexneri [66]. Element pIMDO-S216-3 was typed as IncI1, the most common plasmid type along with IncA/C and commonly isolated from bacteria from human patients and food-producing animals [67]. Element pIMDO-S216-5 was typed as IncHI2, a widely distributed plasmid in Salmonella Typhimurium and relevant in its multidrug resistance spread [68]. Element pIMDO-S216-6, typed as IncF, was characterized as highly prevalent in plasmids recovered from Escherichia coli of food-producing and companion animals [69]. Elements pIMDO-S216-4 and pIMDO-S216-7 displayed no coincidences in the PubMLST database.

The G + C content of the main chromosome was 32.7%. Based on Prokka, the genome contained 3161 genes, of which 3080 were inferred to be protein coding sequences (CDS); 22 to encode ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs), 58 to encode transfer RNAs (tRNAs), and one to encode transfer-messenger RNA (tmRNA).

Ten secondary metabolite BGCs encoding RiPPs were identified with antiSMASH, of which six were found to produce antagonistic compounds and other competitiveness factors of interest. These BGCs were investigated in more detail, as outlined in the following section. The remaining four clusters followed the same manual curation process and were determined as incomplete, since only the core genes – i.e., genes that are considered essential for the basic biological functions and survival of an organism – were identified, whereas the remaining genes completing the biosynthetic pathways were not found in the vicinity. This led to the conclusion that antiSMASH identified partial gene sequences or duplicated genes which did not correspond to functional/complete clusters.

Secondary metabolite BGCs identified within the genome of Staphylococcus shinii IMDO-S216

BGC related to the synthesis of lactococcin 972

The first of the BGCs of interest found by antiSMASH and corroborated by BAGEL4 (Table 2) was located on the reverse strand of the chromosome, spanning a region from position 468,564 to 471,803 (total size of 3,240 nt) and presumably coding for lactococcin 972 (Lcn972) (Fig. 2A). The known biosynthetic pathway of Lcn972 is given in Fig. 3, showing that the pre-bacteriocin of Lcn972, coded for by lclA, is synthesized as a precursor peptide that contains an N-terminal extension (leader peptide) which is cleaved off during maturation by the action of an ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter. Two conserved glycine residues in the precursor are recognized by the ABC transporter, which has the dual function of removing the leader peptide from the precursor and translocating the processed bacteriocin across the plasmid membrane. The immunity protein, coded for by lclB, spans the membrane seven times.

Graphical representation of the in silico or manually annotated BGCs belonging to Staphylococcus shinii IMDO-S216’s genome. The gene clusters code for: the pre-bacteriocin (lclA), the immunity protein (lclB), and the ATP-binding cassette transporter, involved in the synthesis of lactococcin 972 (A); the D-alanine-D-alanyl carrier protein ligase (dltA), D-alanine-to-teichoic acids incorporation protein and possible transporter (dltB), D-alanine-to-carrier transfer protein (dltC), and D-alanine transfer protein from the membrane carrier to teichoic acids (dltD), involved in the D-alanylation of lipoteichoic acids (B); hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl CoA synthase (mvaS), acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase (mvaC), and hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl CoA reductase (mvaA), which are elements of the upper mevalonate pathway (C); phosphomevalonate kinase (mvaK2), mevalonate diphosphate decarboxylase (mvaD), and mevalonate kinase (mvaK1), which form the lower mevalonate pathway (D); dehydrosqualene synthase (crtM), dehydrosqualene desaturase (crtN), diaponeurosporene oxidase (crtP), glycosyl transferase (crtQ), and acyl transferase (crtO), necessary for the synthesis of staphyloxanthin (E); D-ornithine synthetases (sfaBD), pyridoxal-phosphate-dependent amino-acid racemase (sfaC), efflux pump (sfaA), solute-binding protein (htsA), and a permease component of the ABC transporter (htsBC), involved in the synthesis of staphyloferrin A (F); and the quorum sensing system agr formed by the autoinducing peptide (AIP, agrD), the AIP proteolytic processor/transporter (agrB), peptide sensor kinase (agrC), and a transcriptional activator (agrA) (G). Some genes were identified by antiSMASH as core biosynthetic (1), transport-related (2), or additional biosynthetic (3)

Presumed biosynthesis pathway of lactococcin 972 from its annotated genome cluster. The ABC transporter processes the pre-bacteriocin (LclA) and translocates the product across the plasmid membrane. The immunity protein (LclB) protects the producing bacterium from its bacteriocin’s action. Reconstructed after Stoddard et al. (1992), Klaenhammer (1993), Håvarstein et al. (1995), Venema et al. (1995), Nes et al. (1996), and Nes & Eijsink (1999) [70,71,72,73,74,75]

Within the BGC present in S. shinii IMDO-S216, the biosynthetic RiPP-like gene was identified as the pre-bacteriocin-encoding gene (lclA), immediately preceded by the immunity protein-encoding gene (lclB) (Fig. 2A). The encoded pre-bacteriocin protein contained a 23-aa signal peptide. The two conserved glycine residues described above were not found in the leader peptide, although a -GSG- residue sequence was present on positions 17 to 19 from the beginning of the leader peptide, as well as a -GG- residue sequence on positions 31 to 32. At a distance of 300 nucleotides downstream from the immunity protein-encoding gene, a gene coding for an ABC transporter was located; the finding of this gene in the vicinity of the bacteriocin operon confirmed completeness of the cluster. From the comparative analysis, it could be inferred that the presence of a complete lactococcin 972 cluster was not a common trait, occurring only in some S. equorum strains and nine of the S. xylosus strains (Fig. 1). While the ATP-binding cassette transporter gene was ubiquitous in all genomes, either lclA, lclB, or both genes did not reach the minimum homology thresholds in 26 of the genomes selected (Table S1).

BGC related to the D-alanylation of lipoteichoic acids

Another BGC of interest was located on the reverse strand of the chromosome from position 2,149,180 to 2,153,254 (Fig. 2B). This cluster may be involved in the process of D-alanylation of lipoteichoic acids, a component of the cell wall. The resulting cell wall modification displays effects such as resistance against cationic antimicrobial peptides of human, animal, and microbial origin [76]. Another competitiveness-related effect found consisted of an improved adaptation to acidification, paramount in fermentative environments [77]. The dltABCD operon encoded four proteins responsible for the esterification of lipoteichoic acid by D-alanine. In this regard, the product of dltA acts as a D-alanine-D-alanyl carrier protein ligase (Dcl) that transfers a D-alanine to a D-alanine carrier protein (Dcp), encoded by dltC; the product of dltB cooperates in the incorporation of D-alanine into teichoic acids and may play a role in the transfer of D-alanine across the cytoplasmic membrane; and the product of dltD is involved in the transfer of D-alanine from the membrane carrier to teichoic acids.

In S. shinii IMDO-S216, only one standalone gene of this operon (dltA_1) was identified by antiSMASH (data not shown). The other genes (dltBCD) were not found in the vicinity of the cluster. Through manual curation, a complete dltABCD gene cluster was found at the position mentioned above (Fig. 2B). A second standalone dltA gene (dltA_2) was found on the chromosome at position 32,608 to 41,679 (data not shown). Whereas dltA was coding for a protein of 487 amino acids, the dltA_1 and dltA_2 genes were encoding proteins of 1442 and 3023 amino acids, respectively. A manual alignment using blastp revealed that the amino acid sequence encoded by dltA had 95% sequence coverage with a 483- and 472-amino acid section of the sequences encoded by dltA_1 and dltA_2, respectively; dltA shared, in addition, around 30% of sequence identity with both standalone genes. The aligning regions of both dltA_1 and dltA_2 with dltA were located from amino acid position 458 to 941 and amino acid position 482 to 954, respectively. These locations confirm that the presence of homology is prone to be caused by a duplication of the gene and not due to the loss of a stop codon, in which case the homologous regions would be probably located at the beginning of the dltA sequence. The shared conserved region between these homologous genes was an adenylate-forming domain of around 478 nt long. This cluster was complete and present in each of the 38 strains selected for the comparative analysis, with all genes having a substantially higher percentage of identity in all S. xylosus strains and in S. shinii (Fig. 1; Table S1).

BGC related to the synthesis of mevalonate

A gene cluster was inferred to code for the upper mevalonate pathway, located on the chromosome from position 499,590 to 503,300 (total size of 3,711 nt) (Fig. 2C). Mevalonate is one of the central molecules of the biosynthetic pathway of isoprenoids, a pathway that is not only highly conserved through evolution and widely spread through all life forms, but also the origin of some of the most ancient biomolecules identified [78]. Some of the key molecules derived from isoprenoids are, for example, undecaprenyl pyrophosphate, a fundamental element of the cell wall peptidoglycan, as well as menaquinones and ubiquinones, required as electron carriers in the generation of respiratory energy [79].

In staphylococci, six enzymes comprise the mevalonate pathway consisting of both an upper and lower pathway (Fig. 4). The first three enzymes catalyse the conversion from acetyl-CoA to mevalonate (upper pathway). The process starts with three acetyl-CoA units joined consecutively: first through acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase encoded by mvaC, followed by hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A synthase encoded by mvaS to form hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA), which is then reduced to mevalonate through the action of HMG-CoA reductase (mvaA). In the lower pathway, of which the genes were encoded at another location on the chromosome, namely from position 2,479,692 to 2,482,693 (Fig. 2D), mevalonate is phosphorylated and decarboxylated through the enzymes mevalonate kinase (mvaK1), phosphomevalonate kinase (mvaK2), and mevalonate diphosphate decarboxylase (mvaD), resulting in isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP). Both upper and lower mevalonate pathways were present in each strain considered in the comparative analysis, sharing 84.8 to 98.97% and 88.45 to 100% of sequence identity across all genes for all S. xylosus and S. shinii strains, respectively (Table S1).

Predicted biosynthetic pathway of isoprenoids and their by-products in bacteria, after Wilding et al. (2000), Tsubakishita et al. (2010), and Reichert et al. (2018) [80,81,82]. Depicted in green are the enzymes found in the gene cluster identified by antiSMASH, while the enzymes found through manual curation with the use of UniProt and blastp are depicted in orange. HMG-CoA: hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A

BGC related to the synthesis of staphyloxanthin

A gene cluster, located from position 168,352 to 173,857 (total size of 5,506 nt) on the forward strand of the chromosome (Fig. 2E), was inferred to be related with the synthesis of the yellow-orange carotenoid staphyloxanthin, as it contained the crtOPQMN operon. Production of the carotenoid staphyloxanthin reduces susceptibility to killing by hydrogen peroxide and promotes survival of S. aureus in the presence of oxidants [83]. Moreover, a decrease in the production of staphyloxanthins has an effect on membrane fluidity and susceptibility to membrane-targeting antibiotics [84].

The synthesis starts with the condensation of two molecules of farnesyl diphosphate into dehydrosqualene, catalysed by the dehydrosqualene synthase CrtM. This molecule then undergoes dehydrogenation by the dehydrosqualene desaturase CrtN to form 4,4’-diaponeurosporene, which finally undergoes some transformations consisting of oxidation by the diaponeurosporene oxidase CrtP via an aldehyde intermediate, glycosylation by the glycosyl transferase CrtQ, and esterification by the acyl transferase CrtO to produce staphyloxanthin. However, to have a fully operational pathway, a gene encoding a 4,4’-diaponeurosporene aldehyde dehydrogenase (aldH) was missing in the initial genome annotation (Fig. 5). Manual alignment of the amino acid sequence of aldH from the genome of S. aureus subsp. aureus NCTC 8325 to the genome sequence of S. shinii IMDO-S216 showed the presence of a gene encoding 4,4’-diaponeurosporene aldehyde dehydrogenase (aldH1), located from position 1,068,755 to 1,070,134, of which the related amino acid sequence had a 73% sequence identity and a 99% sequence similarity with S. aureus subsp. aureus NCTC 8325 as the query sequence. The comparative analysis showed that all 16 strains of S. xylosus, along with S. shinii, S. pasteuri, S. nepalensis, several S. equorum and two out of eight S. carnosus contained the complete BGC in their genomes. All S. warneri, S. succinus, S. hominis, S. condimenti, one S. equorum, and most S. carnosus strains lacked at least one gene. The genomes of S. equorum KS1030, S. hominis subsp. hominis WiKim0113, and S. succinus 14BME20 specifically lacked all crtOPQMN genes, with the aldH gene being the only one ubiquitous present in all genomes studied. In genomes lacking one or more elements of this BGC, the genes crtO and crtP were found in most cases to not reach minimum homology thresholds against the genome under study, as was the case for S. succinus, S. equorum KS1030, all S. condimenti, and most S. carnosus strains (Fig. 1; Table S1).

BGC related to the synthesis of staphyloferrin A

A gene cluster, located on the chromosome from position 896,013 to 905,180 (total size of 9,168 nt) (Fig. 2F), was hypothesized to be involved in the production of staphyloferrin A (SA). In the genome of S. aureus subsp. aureus NCTC 8325, seven genes are related to the biosynthetic process of this siderophore, which are present in two different loci, located next to each other in the genome (Fig. 6). The first locus in the studied strain consists of the genes sfaDABC, of which the genes sfaB and sfaD encode two synthetases that catalyse the condensation of D-ornithine with two molecules of citrate, sfaC encodes a pyridoxal-phosphate-dependent amino-acid racemase, and sfaA encodes an efflux pump that secretes SA extracellularly. The second locus contains the genes htsABC, of which htsA encodes a predicted solute-binding protein, and htsBC encode a predicted permease component of the ABC transporter required for the uptake of SA.

In the genome of S. shinii IMDO-S216, the two genes identified as core genes corresponded with sfaD and sfaB. Located between sfaD and sfaB, sfaA was found. The gene sfaC was located contiguously to sfaB. Following this locus, the next three genes constituted the htsABC locus and were located downstream, adjoining the sfaDABC cluster. This BGC was widely present in most genomes considered in the comparative genomics analysis (Fig. 1). The only lacking element was the gene sfaA, which had no ortholog present in the genomes of S. equorum KS1039, KM1031, and KS1030, and S. hominis subsp. hominis WiKim0113, whereas it displayed a very low query coverage with the genome of S. equorum C2014 (Fig. 1; Table S1).

This BGC was fairly challenging to identify since the gene identities of this cluster were very similar to the ones producing the siderophores aerobactin and staphyloferrin B, although their biosynthetic processes and gene orientations differed.

BGC related to the synthesis of the accessory gene regulator (Agr) quorum sensing system

A BGC presumably involved in a bacterial quorum sensing system was located on the reverse strand of the chromosome from position 1,046,792 to 1,044,021 (total size of 2,772 nt) (Fig. 2G). This quorum sensing system has been characterized in S. aureus and contains two different loci – the agrBDCA gene cluster and the hld gene (Fig. 7). In general, the autoinducing peptide (AIP) is encoded by the agrD gene. AgrB, characterized as both a proteolytic processor of the AIP and as a transporter, adds a thiolactone ring to AIP and exports it out of the cell. When a threshold concentration is reached, the AIP is detected by the peptide sensor kinase AgrC, which then transfers a phosphate to AgrA, a transcriptional activator. In S. aureus, it activates promoters P2 and P3, resulting in the expression of two transcripts, one related to the agrBDCA gene cluster, the other related to the hld gene encoding the δ-hemolysin. Whereas the full agrBDCA gene locus was found, the hld gene was not present. This gene was however found in twelve of the 38 strains selected for the comparative analysis, with an identity percentage of 64.10% and a query coverage of 88% on all eight S. carnosus strains and both S. condimenti strains, as well as an identity percentage of 80.65% and a query coverage of 88% on S. pasteuri JS7, and an identity percentage of 77.14% and a query coverage of 79% on S. warneri WB224 (results not shown). This quorum sensing system was found to be incomplete in the genomes of all S. carnosus, all S. condimenti, S. homini, S. shinii, S. succinus, and S. warneri strains, and most S. equorum strains, as well as in S. xylosus TCD16. The low query coverage of the gene agrD was the reason of the incompleteness of the BGCs, except for S. warneri WB224, where the gene agrC was found to be non-homologous, and S. xylosus TCD16, which was also lacking agrC and did not contain an ortholog for agrD (Fig. 1; Table S1).

Presumed mode of action of S. shinii IMDO-S216’s quorum sensing mechanism, the staphylococci’s accessory gene regulator (Agr) system. The autoinducing peptide (AgrD) is modified and exported by a proteolytic processor/transporter (AgrB); when surpassing a concentration threshold, the peptide sensor kinase (AgrC) triggers a phosphor transfer, which upregulates the transcription of the agr operon through the P2 promoter. The pathway was reconstructed after Janzon & Arvidson (1990), Reading & Sperandio (2006), and Verdon et al. (2009) [94,95,96]

Discussion

As studied in context with Staphylococcus shinii, Staphylococcus xylosus is one of the most important starter culture species in meat fermentation processes based on its technological properties and its relatively high adaptation to the fermentative environment [9, 17]. In this study, a genome sequencing approach was followed with the aim of revealing key fitness features of a selected S. shinii strain IMDO-S216, formerly classified as S. xylosus IMDO-S216, isolated from fermented meat.

Before entering into a more detailed discussion of the factors involved in survival and competitiveness, some limitations of this study need to be specified. First of all, the exploration of competitiveness-enhancing secondary metabolites was based on the use of the antiSMASH tool, to find secondary metabolite BGCs within the strain’s genome. This engine applies validated ‘rules’ to define which core biosynthetic functions need to be present in a genomic region for it to constitute a BGC. Even if antiSMASH is a widely used tool for genome mining, this approach comes with the limitation of not being exhaustive. More detailed genomic studies may bring different competitive elements to light, as could well be the case with antibiotics, lantibiotics, and bacteriocins. These antimicrobial elements have been described in other species of the genus Staphylococcus. Some examples include the lantibiotic epidermin, identified in Staphylococcus epidermidis [97]; the lantibiotic gallidermin, by Staphylococcus gallinarum [98]; and the antibiotic lugdunin, by Staphylococcus lugdunensis [99]; or bacteriocins such as β-haemolysin, produced by S. lugdunensis; the antimicrobial peptides aureocins A53 and A70, by Staphylococcus aureus; lysostaphin, produced by Staphylococcus simulans biovar staphylolyticus, or its homologous ALE-1 from Staphylococcus capitis [100]; the bacteriocin hyicin 3682, detected in Staphylococcus agnetis 3682; the lantibiotic nisin J, homologous to nisin A, present in S. capitis APC2923; lantibiotic nukacins 3299, L217, and KQU-131, by Staphylococcus simulans, Staphylococcus chromogenes, and Staphylococcus hominis, respectively; or the antibiotic micrococcin P1, produced by strains from distinct bacterial genera, including staphylococci [98, 101]. Other antibiotics that have been originally isolated from other microorganisms can also be produced by staphylococci, as could be the case for tyrocidine, gramicidin A, or gramicidin S, among others [102, 103]. Furthermore, it is important to bear in mind that in silico prediction and annotation do not yield information related to gene expression under the conditions of interest.

A key secondary metabolite BGC found in the completed genome of S. shinii IMDO-S216 revealed the machinery needed to produce a bacteriocin, namely lactococcin 972 (Lcn972). The latter was first isolated from a Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis IPLA 972 strain obtained from a home-made cheese [104, 105], after which it was shown that the bacteriocin-encoding gene cluster was situated on a plasmid [106]. A presumed biosynthesis pathway for the synthesis of Lcn972 in S. shinii IMDO-S216 was found based on its presence in L. lactis subsp. lactis IPLA 972 [106]. The identities of the Lcn972 gene cluster elements were compared to those of the Lactococcus genus: the lclA gene displayed an identity percentage of 32.10% and a query coverage of 84% against L. lactis subsp. lactis IPLA 972; the lclB gene displayed an identity percentage of 25.19% and a query coverage of 37% against L. lactis subsp. lactis IPLA 972; and the ABC transporter displayed an identity percentage of 32.41% and a query coverage of 93% against L. lactis subsp. lactis 972. As described previously, the lclA and ABC transporter gene sequences could be considered as homologous, since their alignment had a minimum sequence identity of 30% and a query coverage of at least 70% [45]. Hypothetically, the fact that a strain previously classified as S. xylosus contains a gene cluster originally identified in a L. lactis subsp. lactis strain could possibly be related to horizontal gene transfer (HGT) within the ecological niche of the teat skin and milk environment, as it is inhabited by both bacterial species [107,108,109,110], but further studies contextualizing the genomic surrounding of this cluster may be necessary to confirm this hypothesis. In S. equorum KS1039, a strain proposed as a potential starter culture for the fermentation of high-salt foods [48], the complete lactococcin 972 gene cluster was as well identified and its expression was experimentally confirmed through the observation of inhibition halos against S. aureus RN4220; the pre-bacteriocin-coding gene of the S. equorum KS1039 strain displayed 70.97% sequence identity at the amino-acid level with that of S. shinii IMDO-S216, on a 100% query cover.

On another note, only specific strains of S. equorum and S. xylosus contained the complete cluster related to the production of lactococcin 972, possibly due to the close relatedness of these two species within Staphylococcus phylogeny [111] (Fig. 1; Table S1).

In its mature state, Lcn972 acts bacteriostatically by blocking septum formation in dividing cells [105, 112, 113]. Its range of activity is fairly narrow, mostly targeting lactococcal strains [106], as is the case for most lactococcal bacteriocins other than lantibiotics [114]. Most other Gram-positive bacteria tested were not affected, including strains belonging to the genera Bacillus, Clostridium, Enterococcus, and Listeria. Likewise, S. shinii IMDO-S216, previously described as S. xylosus IMDO-S216, was not able to inhibit C. botulinum strains in an extensive screening for anticlostridial potential among staphylococci [20]. Nonetheless, even if a starter culture is not able to inhibit common pathogens through its bacteriocin, the latter may still be beneficial because of the potential to improve competitiveness over the background microbiota. Bacteriocinogenic strains have, after all, been studied for their potential to create hurdles in meat and meat products, extending their shelf-life and enhancing food safety [115].

A second BGC coding for a competitiveness factor was related to the D-alanylation of lipoteichoic acids (LTAs), which are cell-wall polymers composed of glycerolphosphate (GroP) polymers with a glycolipid anchor. GroPs can be substituted by D-alanine, which modulates the cell constituent’s polyanionic nature [116, 117]. The consequences of this modification are extensive; mutational studies in diverse bacteria have demonstrated that D-alanylation of LTAs plays a fundamental role in the regulation of autolysis, biofilm formation, and – in the case of S. aureus and Listeria monocytogenes – virulence mechanisms, among other functions [118,119,120]. Another described role of the D-alanylation of LTAs is an increased tolerance to low pH and acidification processes, as shown by the up-regulation of the complete gene cluster in strain S. xylosus C2a during growth in meat models [77]; the four genes involved showed a 96.07%, 96.15%, 96.78%, and 93.63% sequence identity against those of S. shinii IMDO-S216, respectively, on a 100% query cover. The relevance of the action of this BGC may be the reason why it was found in the genomes of all 38 Staphylococcus strains studied (Fig. 1; Table S1). Moreover, this modification provides resistance to staphylococci against cationic antimicrobial peptides produced by animals and humans, as well as by competing microorganisms [121]. The expression of this genomic cluster may affect how bacteria behave in the gut after ingestion of fermented foods, as a lack of LTA D-alanylation may parallel lower survival rates after gastric transit and a hypothetically lower in vivo biofilm formation [122]. Additionally, the dltABCD operon has been identified in several genera [123, 124]. Even if it is not known to which degree the finding of a complete dltABCD gene cluster in the genome of S. shinii IMDO-S216 provides an actual fitness advantage during meat fermentation, it is likely to assume some relevance given the above. The discovery of two standalone genes dltA_1 and dltA_2 merits some discussion. It has generally been considered as a rule of thumb that two sequences are homologous if they are more than 30% identical over their entire lengths [45]. The common conserved region of dltA_1 and dltA_2 belongs to the superfamily of adenylate-forming enzymes, which play a role in a wide range of biological processes, among which ATP-driven adenylation of D-alanine encoded by dltA [125, 126]. The presence of this conserved domain in different genomic locations could be related to the adenylate-forming enzyme function in diverse cell processes. In other words, whereas dltA codes for D-alanylation of lipoteichoic acids, related activities may be offered in other biological contexts under different conditions by dltA_1 and dltA_2.

Another competitiveness feature encoded in the genome of S. shinii IMDO-S216 was related to the biosynthetic pathways of isoprenoids, which have a large range of biological functions [80]. One of the central molecules of these pathways, mevalonate, is the precursor of compounds such as isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) and farnesyl diphosphate (FPP), which in turn are transformed into monoterpenes, sterols, carotenoids, and ubiquinones, to name a few [81]. The function of these compounds includes antibacterial activity, the formation of membrane and cell wall elements, membrane fluidity, protein translation, and electron transport mechanisms, which all increase the bacterium’s adaptability to its environment [81]. Furthermore, some compounds derived from isoprenoids, such as carotenoids, are considered bioactive compounds, associated to health benefits related to immunity, bone, skin, eye and cardiovascular health, among others [127]. The presence of the upper and lower mevalonate biosynthetic gene clusters is highly conserved across all organisms through evolution [80], in line with the results obtained from our comparative analysis (Fig. 1; Table S1). The strain S. xylosus C2a displayed an up-regulation of the complete mevalonate pathway-coding gene cluster involved in the synthesis of FPP, a precursor of carotenoid pigments, when grown in meat models [77]. When alignments were performed, S. xylosus C2a’s mvaSCAK2DK1 genes displayed 98.97%, 97.4%, 96.02%, 98.88%, 96.35%, and 98.05% of amino-acid level sequence identity with the respective genes of S. shinii IMDO-S216 on a 100% query cover. The isoprenoid by-product staphyloxanthin may serve to some degree as a competitiveness factor. This orange pigmentation and C30 carotenoid membrane-bound pigment is typical for S. aureus and used as a main factor to distinguish it from Staphylococcus epidermidis (formerly Staphylococcus albus) [85, 128]. Due to its conjugated double bonds, it participates in host infection and evasion of immune system in S. aureus through the deactivation of reactive oxygen species produced by macrophages and host neutrophils, as well as protecting lipids, proteins, and DNA, being considered as a biological antioxidant and virulence factor in this species [86, 129,130,131]. For S. xylosus, staphyloxanthin seems to play a role in the fluidity of the membrane when grown at low temperatures and in cell survival after freeze-thaw processes [132]. The presence of the aldH gene, described through mutational studies and located around 900 kilobase pairs from the functional gene cluster, seems to complete the enzymatic pathway necessary for the synthesis of the molecule; it has similarly been located in literature hundreds of kilobase pairs away from its respective staphyloxanthin gene cluster [87]. Furthermore, due to CrtP acting as both an oxidase and an aldehyde dehydrogenase [87], this enzyme may be implicated in the synthesis of other structurally or functionally related carotenoids. Based on the various results of the comparative analysis of Staphylococcus strains, from a presence of the complete gene cluster in each S. xylosus strain to the variable presence in the S. equorum strains considered (Fig. 1; Table S1), it could be suggested that individual species present a wide trait variation that may translate in differences in community pigmentation [133]. In S. xylosus C2a, up-regulation of the genes involved in the synthesis of FPP during growth in meat models was followed by an up-regulation of the crtPQMN gene cluster, involved in the carotenoid biosynthesis pathway from FPP, which could explain why this strain produces a yellow pigment when grown on agar medium [77]; amino-acid sequence identities of 89.52%, 80.69%, 79.86%, and 94.20% were found with the respective crtPQMN genes of S. shinii IMDO-S216. To the authors’ knowledge, informational sources that explain the presence of the staphyloxanthin gene cluster in other bacterial species than S. xylosus and S. equorum are not yet available in literature.

Another gene cluster related to competitiveness factors encountered in S. shinii IMDO-S216 was that of staphyloferrin A and may relate to iron acquisition. To overcome iron limitation in the environment, microorganisms possess high affinity iron (III) chelator systems called siderophores, which can be synthesized by molecular platforms called non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPS) in a NRPS-dependent system, or in parallel, through an NRPS-independent siderophore (NIS) synthetase system that uses condensation reactions to form the final siderophore structure [134]. Staphyloferrin A is a dicitrate-based siderophore that is synthesized through a NIS system [135], which is not alien to S. xylosus. The presence of the complete cluster may thus offer S. shinii IMDO-S216, similarly as for S. xylosus, the necessary machinery for the synthesis and utilization of this siderophore system. This, in turn, might provide an enhanced acquisition of iron from the medium in meat matrices, thereby enhancing growth and survival. The presence of siderophores can also be useful in other fermented foods, such as cheese, enabling the desired microorganisms to compete effectively for the necessary iron [136]. In meat models, the expression of the staphyloferrin A synthesis-related gene cluster underwent an up-regulation in S. xylosus C2a [9]; the sfaDABChtsABC gene cluster of S. xylosus C2a displayed degrees of identity from 89.09 to 98.12% to that of S. shinii IMDO-S216. Additionally, this BGC was present in nearly all species considered in the comparative analysis, excepting for S. equorum and S. hominis (Fig. 1; Table S1). The presence of other siderophores involved in iron uptake, such as lactoferrin and ferritin, in S. hominis has been hypothesized in literature, whereas no information about S. equorum’s iron transport systems was found [137]. Other iron transport systems have been described in S. xylosus C2a in addition to the Sfa and Hts systems described above, such as Sit, Fhu, and Sst [9]. Finally, an Agr quorum sensing system was identified. The term quorum sensing has been collectively designated for those mechanisms through which bacteria regulate gene expression via cell density. Three main quorum sensing systems have been described, one being specific for Gram-negative bacteria, another being specific for Gram-positive bacteria, and a third system that is considered universal [94]. The Gram-positive quorum sensing mechanism usually involves small peptides that are modified and exported until they reach a threshold concentration, after which they are recognized by sensor kinases that launch a phosphate group-transfer to a response regulator [138]. The Agr system, as described previously, is autoinduced through an extracellular ligand, namely the AIP, acting as a sensor of cell density and usually reaching its threshold around mid- to late-exponential phase [95, 139]. RNAIII, one of the produced effector transcripts of the Agr system, is described as a relevant bacterial virulence element in S. aureus, with some RNAIII-inhibiting peptide studies demonstrating its implication in biofilm formation and toxin production [140, 141]. In S. shinii IMDO-S216, the complete agrBDCA cluster was identified, while the hld gene was not found through manual annotation. The transcription of this gene and the activation of its promoter, P3, presumably lead to the expression of various genes involved in the synthesis of several virulence factors and exoproteins in S. aureus [94,95,96]. Even if virulence factors that pertain to S. aureus, such as δ-hemolysin, are usually not a concern for CNS strains [142,143,144], the quorum sensing mechanism is potentially implicated in bacterial communication mechanisms in S. shinii IMDO-S216.

In fermented meat products, elements pertaining to quorum sensing communication systems have been studied to decontaminate or control growth of Listeria monocytogenes without affecting beneficial bacteria in the process [145]. This highlights that quorum sensing systems may contribute to the quality and safety of fermented meat products. The presence of this genomic feature in nearly all S. xylosus strains, as well as in all strains from S. nepalensis, S. pasteuri JS7, and S. equorum KS1039, indicates the prevalence of a shared communication system (Fig. 1; Table S1). Also, as previously mentioned, the hld gene is present in twelve of the 38 strains selected for the comparative analysis. The identical sequence identity and query coverage percentages between S. carnosus and S. condimenti may be explained by their phylogenetic proximity [111]. Since April 2020, S. carnosus DSM 25,010 is considered as GRAS (Generally Recognized As Safe) [146] by the Food and Drug Administration, whereas this is not the case for the other bacteria referenced in this study. However, it has been shown that CNS isolates from blood culture usually express several virulence genes similar to those carried by S. aureus [147], which may not directly imply the pathogenicity of the bacterium.

Conclusions

The genome of Staphylococcus shinii IMDO-S216 was found to contain a circular chromosome and eight plasmid replicons, that were then screened for the presence of genes coding for secondary metabolites. The complete gene cluster of lactococcin 972 was found on the main chromosome. In addition to this potential to generate a bacteriocin, other competitiveness factors were linked to several complete gene clusters located on the chromosome. These clusters coded for elements related to the D-alanylation of lipoteichoic acids on the cell wall; the synthesis of mevalonate and one of its by-products, namely staphyloxanthin; the synthesis of staphyloferrin A; and the Agr quorum sensing system. All these gene clusters were equally studied in 38 selected staphylococcal species with a nearly-complete or complete assembled genome, displaying an ubiquitous presence for the D-alanylation of lipoteichoic acids and the synthesis of mevalonate, and a more differentiated appearance for the other BGCs. Taken together, such factors may account for an enhanced adaptation and competitiveness of the studied strain in a meat fermentation environment, offering advantages like growth at low temperatures, intake of iron necessary for growth, efficient communication through a quorum sensing system, or protection against certain antimicrobial peptides. The combination of these competitiveness factors underlines the fitness of S. shinii IMDO-S216 in a fermented meat matrix. A further exploration of the expression of these gene clusters and the biosynthesis of their products will lead to an improved understanding of the functionality of this strain during meat fermentation.

Data availability

The complete assembled genome of S. shinii IMDO-S216 has been deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive at EMBL-EBI with BioProject accession number PRJEB56928 (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/browser/view/PRJEB56928).

Abbreviations

- ABC:

-

ATP-binding cassette

- Agr:

-

Accessory gene regulator

- AIP:

-

Autoinducing peptide

- BGC:

-

Biosynthetic gene cluster

- Blastn:

-

Basic local alignment search tool for nucleotides

- Blastp:

-

Basic local alignment search tool for proteins

- CD:

-

Coding sequence

- CNS:

-

Coagulase-negative staphylococci

- FPP:

-

Farnesyl diphosphate

- GCC:

-

Gram-positive, catalase-positive cocci

- GRAS:

-

Generally Recognized As Safe

- GroP:

-

Glycerolphosphate

- HGT:

-

Horizontal gene transfer

- HMG-CoA:

-

Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A

- IPP:

-

Isopentenyl diphosphate

- Lcn972:

-

Lactococcin 972

- LTA:

-

Lipoteichoic acids

- NRPS:

-

Non-ribosomal peptide synthetase

- ONT:

-

Oxford Nanopore Technologies

- RiPP:

-

Ribosomally-synthesized and posttranslationally modified peptides

- SA:

-

Staphyloferrin A

References

Cho GS, Li B, Brinks E, Franz CMAP. Characterization of antibiotic-resistant, coagulase-negative staphylococci from fresh produce and description of Staphylococcus Shinii sp. Nov. isolated from chives. J Microbiol. 2022;60(9):877–89.

Oren A, Göker M. Validation list 209. Valid publication of new names and new combinations effectively published outside the IJSEM. Int J Syst Evol Micr. 2023;73:1–8.

Kong H, Jeong DW, Liu J, Lee JH. Complete genome sequence of Staphylococcus pseudoxylosus 14AME19 exhibiting a weak hemolytic activity. Korean J Microbiol. 2021;57:109–11.

Graña-Miraglia L, Arreguín-Pérez C, López-Leal G, Muñoz A, Pérez-Oseguera A, Miranda-Miranda E, et al. Phylogenomics picks out the par excellence markers for species phylogeny in the genus Staphylococcus. PeerJ. 2018;2018:1–16.

Naushad S, Barkema HW, Luby C, Condas LAZ, Nobrega DB, Carson DA et al. Comprehensive phylogenetic analysis of bovine non-aureus staphylococci species based on whole-genome sequencing. Front Microbiol. 2016;7 DEC.

Macfadyen AC, Leroy S, Harrison EM, Parkhill J, Holmes MA, Paterson GK. Staphylococcus pseudoxylosus sp. Nov., isolated from bovine mastitis. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2019;69:2208–13.

Cruxen CE, dos Funck S, Haubert GD, Dannenberg L, da Marques G, de Chaves J. Selection of native bacterial starter culture in the production of fermented meat sausages: application potential, safety aspects, and emerging technologies. Food Res Int. 2019;122(October 2018):371–82.

Kloos WE, Schleifer KH. Isolation and characterization of staphylococci from human skin. II. Descriptions of four new species: Staphylococcus warneri, Staphylococcus capitis, Staphylococcus hominis, and Staphylococcus simulans. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1975;25(1):62–79.

Leroy S, Vermassen A, Ras G, Talon R. Insight into the genome of Staphylococcus xylosus, a ubiquitous species well adapted to meat products. Microorganisms. 2017;5(3).

De Buck J, Ha V, Naushad S, Nobrega DB, Luby C, Middleton JR, et al. Non-aureus staphylococci and bovine udder health: current understanding and knowledge gaps. Front Vet Sci. 2021;8(April):1–16.

Brand YE, Rufer B. Late prosthetic knee joint infection with Staphylococcus xylosus. IDCases. 2021;24:e01160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idcr.2021.e01160.

Wojtyczka RD. Analysis of the polymorphism of Staphylococcus strains isolated from a hospital environment. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2011;11(58):1–7.

Kumar P, Chatli MK, Verma AK, Mehta N, Malav OP, Kumar D, et al. Quality, functionality, and shelf life of fermented meat and meat products: a review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2017;57(13):2844–56.

Sánchez Mainar M, Stavropoulou DA, Leroy F. Exploring the metabolic heterogeneity of coagulase-negative staphylococci to improve the quality and safety of fermented meats: a review. Int J Food Microbiol. 2017;247:24–37.

Geeraerts W, Stavropoulou DA, De Vuyst L, Leroy F. Meat and meat products. In: Azcarate-Peril MA, Arnold RR, Bruno-Bárcena JM, editors. How fermented foods feed a healthy gut microbiota: a nutrition continuum. United States of America: Springer; 2019. pp. 57–90.

Stavropoulou DA, De Vuyst L, Leroy F. Nonconventional starter cultures of coagulase-negative staphylococci to produce animal-derived fermented foods, a SWOT analysis. J Appl Microbiol. 2017;125:1570–86.

Laranjo M, Potes ME, Elias M. Role of starter cultures on the safety of fermented meat products. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:1–11.

Sánchez Mainar M, Leroy F. Process-driven bacterial community dynamics are key to cured meat colour formation by coagulase-negative staphylococci via nitrate reductase or nitric oxide synthase activities. Int J Food Microbiol. 2015;212:60–6.

Sánchez Mainar M, Xhaferi R, Samapundo S, Devlieghere F, Leroy F. Opportunities and limitations for the production of safe fermented meats without nitrate and nitrite using an antibacterial Staphylococcus sciuri starter culture. Food Control. 2016;69:267–74.

Van der Veken D, Benhachemi R, Charmpi C, Ockerman L, Poortmans M, Van Reckem E et al. Exploring the ambiguous status of coagulase-negative staphylococci in the biosafety of fermented meats: the case of antibacterial activity versus biogenic amine formation. Microorganisms. 2020;8(2).

García-Díez J, Saraiva C. Use of starter cultures in foods from animal origin to improve their safety. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(5):1–25.

Barcenilla C, Ducic M, López M, Prieto M, Álvarez-Ordóñez A. Application of lactic acid bacteria for the biopreservation of meat products: a systematic review. Meat Sci. 2022;183.

Shi C, Maktabdar M. Lactic acid bacteria as biopreservation against spoilage molds in dairy products – A review. Front Microbiol. 2022;12.

Mak P. Staphylococcal bacteriocins. In: Savini V, editor. Pet-to-man travelling staphylococci: A world in progress. United States of America: Elsevier Inc.; 2018. pp. 161–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-813547-1.00013-3.

Matikevičienė V, Grigiškis S, Lubytė E, Dienys G. Partial purification and characterization of bacteriocin-like peptide produced by Staphylococcus xylosus. Vide Tehnol Resur - Environ Technol Resour. 2017;3:213–6.

Schiffer C, Hilgarth M, Ehrmann M, Vogel RF. Bap and cell surface hydrophobicity are important factors in Staphylococcus xylosus biofilm formation. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:1–10.

Bauer MA, Kainz K, Carmona-Gutierrez D, Madeo F. Microbial wars: competition in ecological niches and within the microbiome. Microb Cell. 2018;5(5):215–9.

Stubbendieck RM, Straight PD. Multifaceted interfaces of bacterial competition. J Bacteriol. 2016;198(16):2145–55.

Simonová M, Strompfová V, Marciňáková M, Lauková A, Vesterlund S, Moratalla ML, et al. Characterization of Staphylococcus xylosus and Staphylococcus carnosus isolated from Slovak meat products. Meat Sci. 2006;73(4):559–64.

Leroy S, Lebert I, Andant C, Talon R. Interaction in dual species biofilms between Staphylococcus xylosus and Staphylococcus aureus. Int J Food Microbiol. 2020;326:108653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2020.108653.

Stavropoulou DA, Van Reckem E, De Smet S, De Vuyst L, Leroy F. The narrowing down of inoculated communities of coagulase-negative staphylococci in fermented meat models is modulated by temperature and pH. Int J Food Microbiol. 2018;274:52–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2018.03.008.

Van der Veken D, Hollanders C, Verce M, Michiels C, Ballet S, Weckx S et al. Genome-based characterization of a plasmid-associated micrococcin P1 biosynthetic gene cluster and virulence factors in Mammaliicoccus Sciuri IMDO-S72. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2022;88(4).

Jain M, Olsen HE, Paten B, Akeson M. The Oxford Nanopore MinION: delivery of nanopore sequencing to the genomics community. Genome Biol. 2016;17(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-016-1103-0.

De Coster W, D’Hert S, Schultz DT, Cruts M, Van Broeckhoven C. NanoPack: visualizing and processing long-read sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2018;34(15):2666–9.

Andrews S. FastQC: a quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. 2010. http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/.

Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B, Trimmomatic. A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(15):2114–20.

Wick RR, Judd LM, Gorrie CL, Holt KE, Unicycler. Resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS Comput Biol. 2017;13(6):1–22.

Wick RR, Schultz MB, Zobel J, Holt KE. Bandage: interactive visualization of de novo genome assemblies. Bioinformatics. 2015;31(20):3350–2.

Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(17):3389–402.

Tatusova TA, Madden TL. BLAST 2 SEQUENCES, a new tool for comparing protein and nucleotide sequences. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;174(2):247–50.

Jolley KA, Bray JE, Maiden MCJ. Open-access bacterial population genomics: BIGSdb software, the PubMLST.org website and their applications. Wellcome Open Res. 2018;3(124):1–20.

Seemann T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. 2014;30(14):2068–9.

Blin K, Shaw S, Kloosterman AM, Charlop-Powers Z, Van Wezel GP, Medema MH, et al. AntiSMASH 6.0: improving cluster detection and comparison capabilities. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49(W1):W29–35.

Gerts EM, Yu YK, Agarwala R, Schäffer AA, Altschul SF. Composition-based statistics and translated nucleotide searches: improving the TBLASTN module of BLAST. BMC Biol. 2006;4:1–14.

Pearson WR. An introduction to sequence similarity (homology) searching. Curr Protoc Bioinforma. 2013;42(10):1–8. http://edupediapublications.org/journals/index.php/ijr/article/view/964.

Rosenstein R, Nerz C, Biswas L, Resch A, Raddatz G, Schuster SC et al. Genome analysis of the meat starter culture bacterium Staphylococcus carnosus TM300. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75(3):811–22. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19060169.

Dong H, Chen J, Hastings AK, Guo L, Zheng B. Complete genome sequence and comparative analysis of Staphylococcus condimenti DSM 11674, a potential starter culture isolated from soy sauce mash. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2017;5:6–11.

Jeong DW, Na H, Ryu S, Lee JH. Complete genome sequence of Staphylococcus equorum KS1039 isolated from saeu-jeotgal, Korean high-salt-fermented seafood. J Biotechnol. 2016;219:88–9.

Heo S, Park J, Lee E, Lee JH, Jeong DW. Transcriptomic analysis of Staphylococcus equorum KM1031, isolated from the high-salt fermented seafood jeotgal, under salt stress. Fermentation. 2022;8(8).

Kim T, Heo S, Lee JH, Jeong DW. Complete genome sequence of Staphylococcus equorum KS1030 exhibiting acquired lincomycin resistance. Korean J Microbiol. 2021;57(3):210–2.

Jeong DW, Lee JH. Complete genome sequence of Staphylococcus succinus 14BME20 isolated from a traditional Korean fermented soybean food. Am Soc Microbiol. 2017;1–2.

Ma APY, Jiang J, Tun HM, Mauroo NF, Yuen CS, Leung FCC. Complete genome sequence of Staphylococcus xylosus HKUOPL8, a potential opportunistic pathogen of mammals. Genome Announc. 2014;2(4):13–4.

Labrie SJ, El Haddad L, Tremblay DM, Plante PL, Wasserscheid J, Dumaresq J, et al. First complete genome sequence of Staphylococcus xylosus, a meat starter culture and a host to propagate Staphylococcus aureus phages. Genome Announc. 2014;2(4):10–1.

Heo S, Lee JH, Jeong DW. Complete genome sequence of Staphylococcus xylosus strain DMSX03 from fermented soybean, meju. Korean J Microbiol. 2021;57(1):52–4.

Bateman A, Martin MJ, Orchard S, Magrane M, Agivetova R, Ahmad S, et al. UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49(D1):D480–9.

Lu S, Wang J, Chitsaz F, Derbyshire MK, Geer RC, Gonzales NR, et al. CDD/SPARCLE: the conserved domain database in 2020. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48D1:D265–8.

Bernhofer M, Dallago C, Karl T, Satagopam V, Heinzinger M, Littmann M, et al. PredictProtein - Predicting protein structure and function for 29 years. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49(1):W535–40.

Liu B, Zheng D, Jin Q, Chen L, Yang J. VFDB 2019: a comparative pathogenomic platform with an interactive web interface. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47D1:D687–92.

Van Heel AJ, De Jong A, Song C, Viel JH, Kok J, Kuipers OP. BAGEL4: a user-friendly web server to thoroughly mine RiPPs and bacteriocins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(W1):W278–81.

Carver T, Harris SR, Berriman M, Parkhill J, McQuillan JA. Artemis: an integrated platform for visualization and analysis of high-throughput sequence-based experimental data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(4):464–9.

Wickham H. ggplot2: Elegant graphics for data analysis. 2016. https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org.

Wilkins D. Gggenes: draw gene arrow maps in ‘ggplot2’. R package version 0.4.1. 2020. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=gggenes/.

Rstudio Team. Rstudio: integrated development for R. Rstudio Inc., Boston, Massachusetts, United States of America. 2018. https://www.rstudio.com/.

Inkscape Project. Inkscape. 2020. Available at: https://inkscape.org/.

Novick RP, Hoppensteadt FC. On plasmid incompatibility. Plasmid. 1978;1:421–34.

Diaz-Orejas R, Espinosa M, Yeo CC. The importance of the expendable: toxin-antitoxin genes in plasmids and chromosomes. Front Microbiol. 2017;8(1479):1–7.

Foley SL, Kaldhone PR, Ricke SC, Han J. Incompatibility group I1 (IncI1) plasmids: their genetics, biology, and public health relevance. Microbiol Mol Biol R. 2021;85(2):1–24.

Zhang J-F, Fang L-X, Chang M-X, Cheng M, Zhang H, Long T-F et al. A trade-off for maintenance of multidrug resistant IncHI2 plasmids in Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium through adaptive evolution. 2022;7(5):1–18.

Yang Q-E, Sun J, Li L, Deng H, Liu B-T, Fang L-X, et al. IncF plasmid diversity in multi-drug resistant Escherichia coli strains from animals in China. Front Microbiol. 2015;6(964):1–9.

Stoddard GW, Petzel JP, Van Belkum MJ, Kok J, McKay LL. Molecular analyses of the lactococcin A gene cluster from Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis biovar diacetylactis WM4. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58(6):1952–61.

Klaenhammer TR. Genetics of bacteriocins produced by lactic acid bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1993;12(1–3):39–85.

Håvarstein LS, Diep DB, Nes IF. A family of bacteriocin ABC transporters carry out proteolytic processing of their substrates concomitant with export. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16(2):229–40.

Venema K, Venema G, Kok J, Lactococcins. Mode of action, immunity and secretion. Int Dairy J. 1995;5(8):815–32.

Nes IF, Diep DB, Håvarstein LS, Brurberg MB, Eijsink V, Holo H. Biosynthesis of bacteriocins in lactic acid bacteria. Anton Leeuw Int J Gen Mol Microbiol. 1996;70(2–4):113–28.

Nes IF, Eijsink VGH. Regulation of group II peptide bacteriocin synthesis by quorum-sensing mechanisms. In: Dunny GM Dunny, Winans, editors. Cell-cell signaling in bacteria. Washington DC:ASM Press;1999. pp. 175–192.

Winstel V, Xia G, Peschel A. Pathways and roles of wall teichoic acid glycosylation in Staphylococcus aureus. Int J Med Microbiol. 2014. 304:215–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmm.2013.10.009.

Vermassen A, Dordet-Frisoni E, De La Foye A, Micheau P, Laroute V, Leroy S, et al. Adaptation of Staphylococcus xylosus to nutrients and osmotic stress in a salted meat model. Front Microbiol. 2016;7(87):1–17.

Holstein SA, Hohl RJ. Isoprenoids: remarkable diversity of form and function. Lipids. 2004;39(4):293–309.

Balibar CJ, Shen X, Tao J. The mevalonate pathway of Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 2009;191(3):851–61.

Wilding EI, Brown JR, Bryant AP, Chalker AF, Holmes DJ, Ingraham KA, et al. Identification, evolution, and essentiality of the mevalonate pathway for isopentenyl diphosphate biosynthesis in Gram-positive cocci. J Bacteriol. 2000;182(15):4319–27.

Reichert S, Ebner P, Bonetti EJ, Luqman A, Nega M, Schrenzel J, et al. Genetic adaptation of a mevalonate pathway deficient mutant in Staphylococcus aureus. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1–14.

Tsubakishita S, Kuwahara-Arai K, Sasaki T, Hiramatsu K. Origin and molecular evolution of the determinant of methicillin resistance in staphylococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54(10):4352–9.

Hall JW, Yang J, Guo H, Ji Y. The Staphylococcus aureus AirSR two-component system mediates reactive oxygen species resistance via transcriptional regulation of staphyloxanthin production. Infect Immun. 2016;85(2):1–12.

Valliammai A, Selvaraj A, Muthuramalingam P, Priya A, Ramesh M, Pandian SK. Staphyloxanthin inhibitory potential of thymol impairs antioxidant fitness, enhances neutrophil mediated killing and alters membrane fluidity of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Biomed Pharmacoter. 2021;141:1–11.

Pelz A, Wieland KP, Putzbach K, Hentschel P, Albert K, Götz F. Structure and biosynthesis of staphyloxanthin from Staphylococcus aureus. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(37):32493–8.

Yehia FAA, Yousef N, Askoura M. Celastrol mitigates staphyloxanthin biosynthesis and biofilm formation in Staphylococcus aureus via targeting key regulators of virulence; in vitro and in vivo approach. BMC Microbiol. 2022;22(1):1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-022-02515-z.

Kim SH, Lee PC. Functional expression and extension of staphylococcal staphyloxanthin biosynthetic pathway in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(26):21575–83.

Beasley FC, Vinés ED, Grigg JC, Zheng Q, Liu S, Lajoie GA, et al. Characterization of staphyloferrin a biosynthetic and transport mutants in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol. 2009;72(4):947–63.

Cheung J, Beasley FC, Liu S, Lajoie GA, Heinrichs DE. Molecular characterization of staphyloferrin B biosynthesis in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol. 2009;74(3):594–608.

Beasley FC, Heinrichs DE. Siderophore-mediated iron acquisition in the staphylococci. J Inorg Biochem. 2010;104(3):282–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2009.09.011.

Laakso HA, Marolda CL, Pinter TB, Stillman MJ, Heinrichs DE. A heme-responsive regulator controls synthesis of staphyloferrin B in Staphylococcus aureus. J Biol Chem. 2016;291(1):29–40. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M115.696625.

Flannagan RS, Brozyna JR, Kumar B, Adolf LA, Power JJ, Heilbronner S et al. In vivo growth of Staphylococcus lugdunensis is facilitated by the concerted function of heme and non-heme iron acquisition mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 2022;298(5):101823. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbc.2022.101823.

van Dijk MC, de Kruijff RM, Hagedoorn PL. The role of iron in Staphylococcus aureus infection and human disease: a metal tug of war at the host—microbe interface. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022;10:1–7.

Reading NC, Sperandio V. Quorum sensing: the many languages of bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2006;254(1):1–11.

Verdon J, Girardin N, Lacombe C, Berjeaud JM, Héchard Y. ∆-Hemolysin, an update on a membrane-interacting peptide. Peptides. 2009;30(4):817–23.

Janzon L, Arvidson S. The role of the δ-lysin gene (hld) in the regulation of virulence genes by the accessory gene regulator (agr) in Staphylococcus aureus. EMBO J. 1990;9(5):1391–9.

Hansen JN. Antibiotics synthesized by posttranslational modification. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1993;47:535–64.