Abstract

Background

Meiotic recombination is a fundamental genetic process that shuffles allele combinations and promotes accurate segregation of chromosomes. Analyses of the ubiquitous variation of recombination rates within and across species suggest that recombination is evolving adaptively. All studied insects with advanced eusociality have shown exceptionally high recombination rates, which may represent a prominent case of adaptive evolution of recombination. However, our understanding of the relationship between social evolution and recombination rates is incomplete, partly due to lacking empirical data. Here, we present a linkage map of the monandrous, advanced eusocial Brazilian stingless bee, Frieseomelitta varia, providing the first recombination analysis in the diverse Meliponini (Hymenoptera, Apidae).

Results

Our linkage map includes 1417 markers in 19 linkage groups. This map spans approximately 2580 centimorgans, and comparisons to the physical genome assembly indicate that it covers more than 75 % of the 275 Megabasepairs (Mbp) F. varia genome. Thus, our study results in a genome-wide recombination rate estimate of 9.3–12.5 centimorgan per Mbp. This value is higher than estimates from nonsocial insects and comparable to other highly social species, although it does not support our prediction that monandry and strong queen-worker caste divergence of F. varia lead to even higher recombination rates than other advanced eusocial species.

Conclusions

Our study expands the association between elevated recombination and sociality in the order Hymenoptera and strengthens the support for the hypothesis that advanced social evolution in hymenopteran insects invariably selects for high genomic recombination rates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Meiotic recombination is a universal process in sexual organisms that facilitates accurate segregation of chromosomes, which is achieved by the physical connection between homologous chromosomes. This connection depends on the formation of at least one reciprocal exchange between homologous chromosomes, a crossover [1]. In most eukaryotes, these crossover events occur once or twice per chromosome pair during meiosis [2]. The narrow range is presumably a consequence of a rather invariant selection for a minimal number of crossovers that are required to avoid aneuploidy while minimizing the risk of genomic instability or other deleterious effects of recombination [3]. However, recombination also allows for a reciprocal exchange of genetic material, facilitating adaptive evolution [4]. Explanations of these evolutionary benefits include the reduction of Hill-Robertson interference [5], the “Red Queen” hypothesis [6], and avoidance of Muller’s rachet [7]. The process of meiotic recombination increases the efficiency of natural selection by shuffling allele combinations in offspring and can create a greater genotypic variation that selection can act upon [8]. Based on these evolutionary arguments, the recombination rate is predicted to vary more widely than what is structurally required. Accordingly, recombination rate varies significantly across species, populations, and individuals [9,10,11], in addition to local variation within genomes [12]. Some of this variation can be linked to directional selection and environmental fluctuation, while some may be non-adaptive, and yet other variation may be reported due to measurement errors [12,13,14,15,16].

The high recombination rates of social Hymenoptera present a prominent case of recombination rates that are above the minimally required crossover numbers to guarantee proper chromosome segregation [17,18,19,20,21,22]. Reports of high recombination rates in all studied social hymenopteran species – four honey bees, two ants, one wasp, and one bumblebee – support this notion when compared to the lower recombination rates of solitary hymenopterans [19, 23]. Social evolution in the order Hymenoptera has led repeatedly to highly complex societies with reproductive division of labor, cooperative brood care, and overlapping generations [24]. Social insects vary in social complexity [25], and the level of social complexity may be related to recombination rate [20, 26].

Current hypotheses to explain the high recombination rates of social insects can be principally divided into several arguments. The first set is based on a short-term evolutionary advantage of recombination by increasing genotypic diversity to enhance disease resistance, division of labor, or potentially other factors [18, 19, 23]. Genetic diversity arguments have also been proposed to explain multiple mating by females (polyandry) in social Hymenoptera [27] and supported by numerous empirical studies [28, 29]. However, modeling indicates that polyandry leads to a much stronger increase in offspring genetic diversity than any recombination effect and therefore it has been argued that increased recombination is unlikely to have evolved by selection on colony genetic diversity [30]. The second argument is based on the idea that increased recombination rates have been selected for to facilitate the rapid, independent evolution of caste-specific genes in social insects and allow the evolution of caste differences [31]: High recombination may facilitate the divergence of queen and worker phenotypes, especially when worker- and queen- selected genes are physically close [32]. Correlations between recombination rate and the location of genes that are important for caste-specific functions support this argument [31, 33]. However, these correlations have not been consistently found even in the same species Apis mellifera [34], making this argument contentious [23]. A third argument, the potential for high genomic recombination to reduce the potential for kin conflict [35, 36] and selfish genetic elements [37] in social insects, is also plausible. The lack of a clear correlation between chromosome number and sociality [38] argues against this “reduction of genetic conflict” hypothesis, but selfish genetic elements enabled by reduced recombination certainly exist in the form of “social chromosomes” in genetically heterogeneous social insect societies [39]. Thus, more empirical data are needed to evaluate the validity of these theoretical arguments.

In addition to their high genomic recombination rates, the socially complex ant, wasp, and honey bee species share important sociobiological features [40]. All of these species are polyandrous even though monandry was the ancestral state in each clade [41]. While polyandry may indicate selection for genetic diversity within colonies, recombination and polyandry may both increase genotypic diversity. Thus, we are predicting that monandrous species with advanced eusociality exhibit higher recombination rates than comparable polyandrous species if recombination is selected to increase intra-colonial genetic diversity. However, this prediction has not yet been tested. Furthermore, colonies of all investigated species contain only one reproductive queen, which is physically diverged from the worker castes. Nevertheless, workers have retained a functional ovary in all these species, indicating that queen-worker divergence is not as complete as in species with completely sterile workers. Based on a stronger divergent selection between worker- and queen-specific genes in species with complete worker sterility, such species are predicted to exhibit particularly high recombination rates based on the second of the above hypotheses.

An important taxon of social insects that has not yet been investigated regarding genomic recombination rates is the stingless bees (Meliponini), which make up the most specious tribe in the Apinae [42]. Stingless bees exhibit advanced eusociality and include several species that are essential pollinators in tropical ecosystems [43]. The pantropical distribution of stingless bees suggests that their origin dates back to the ancient Gondwana supercontinent more than 100 million years ago [44]. Despite their ecological relevance and biodiversity of about 600 described species in 60 genera, stingless bees remain understudied in all aspects, including their social behavior and genomic features [45, 46], such as recombination. This deficit contrasts particularly with honey bees, which only represent one genus of ten species that evolved during the past 25 million years [47]. Multiple studies within and across species of honey bees document their exceptional recombination rates, ranging from 17.4 to 37.0 centimorgan (cM) per megabase (Mb) [17, 21, 22, 33, 48, 49]. Stingless bees have presumably diverged from honey bees over 80 million years ago, and it is unclear how social their common ancestor was [42]. Stingless bees rival honey bees in social complexity, are predominantly monandrous, and can have completely sterile workers [50,51,52,53]. Thus, based on both, genotypic diversity and caste divergence model, they are predicted to exhibit even higher recombination rates than honey bees. Stingless bees are also the most important missing taxon to assess the link between eusociality and high recombination rates in the Hymenoptera.

Frieseomelitta varia (Lepeletier, 1836) is a Neotropical, medium-sized species of stingless bee that occurs in several parts of Brazil [54]. Living in large colonies with one monandrous queen, F. varia workers are completely sterile with heavily modified and non-functional ovaries [50]. The genome of F. varia has been sequenced and assembled [55]. Hence, we chose F. varia to construct a high-quality recombination map using SNP markers, benefitting from recent advances in sequencing technology and the large number of haploid sons produced by a single female in this species.

Results

The sequencing of genomic DNA of 180 F. varia males from a single mother resulted in highly variable numbers of high-quality reads ranging from 60,427 to 48,610,455 (mean: 13,428,476 ± 10,517,236 SD). A draft genome sequence for this mapping population was created from two individuals with highest read counts. These data from two individuals proved sufficient for a 301 Mbp assembly with an average GC content of 37 % (Table 1). This assembly was used as a direct reference for SNP calling to only discover the SNPs that were segregating in our mapping population. However, for downstream analyses the published, more contiguous genome Fvar_1.2 [55] was used. On average, 81 % (± 0.03 % SD) of the reads from each sample aligned to this reference (Table S1), and 9514 SNP markers were extracted after preliminary quality filtering.

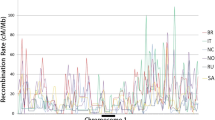

After filtering the original set of 9514 markers as described in methods, 1023 unique SNP markers were included in constructing the initial linkage map. The resulting map contained 20 linkage groups ranging from 49.5 cM to 242.9 cM, totaling 2573.2 cM. Post-hoc addition of previously excluded markers joined ends of two linkage groups but did not close any remaining linkage gaps (> 20 cM). The final map of F. varia comprised 1417 high-quality SNP markers assembled into 19 linkage groups (Fig. 1). Thus, the map is containing 4 extra linkage groups compared to 15 previously reported chromosomes [56]. The final map length was 2557.9 cM with linkage groups ranging from 42.0 cM to 295.4 cM. The average marker density was 0.55 markers per cM. The highest density was observed for group 12 (one marker every 1.03 cM), whereas group 15 had the lowest density (one marker every 3.31 cM) (Table 2). Based on a physical genome size of 275 Mb [55], the genetic map length resulted in a minimum estimate of 9.3 cM/Mb for the genome-wide recombination rate of F. varia.

Linkage map of F. varia. The final genetic length of the map was 2558 cM, which consisted of 19 linkage groups ranging from 42 cM to 295 cM. The linkage groups are sorted according to descending marker numbers from 158 markers in LG1 to 18 markers in LG19. Further efforts to end-join any of these linkage groups failed. Each horizontal black line indicates an SNP marker, and their vertical position indicates recombination distances among markers. The color depicts approximate marker density within linkage groups. For complete plot with marker labels and positions please refer Supplementary Fig. 1

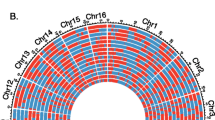

The location of 99.1 % of the mapped SNPs was identified in Fvar_1.2 based on best nBLAST results (Table S2). The SNP sequences mapped to 563 unique scaffolds (25.9 % of all scaffolds) with a combined length of 204.8 Mb, representing 74.5 % of the total genome (Table 2). Scaffolds that were covered by our linkage map were much larger (median length = 260,348 bp) than scaffolds that were not represented (median = 4141 bp). The alignment of scaffolds to our linkage map uniquely mapped 451 scaffolds to our 21 linkage groups while 112 scaffolds mapped to multiple linkage groups (Fig. 2 and Figure S1). Based on the overall genome coverage of 74.5 %, the maximum estimate for the genome-wide recombination rate of F. varia equals 12.5 cM/Mb (2558 cM / 275 Mb * 0.745). On the basis of the length of the matching scaffolds, the average recombination rate for each linkage group was calculated, ranging from 9.6 to 17.5 cM/Mb (Table 2). A negative relationship between the average recombination rate of linkage groups and their physical length was observed, but this was not significant (Spearman’s correlation, R= -0.38, n = 19, p-value = 0.11; Figure S2).

Example of genomic scaffold alignment to the linkage map of F. varia. Most of the genome scaffolds (Fvar_1.2) matched to sequences associated with SNPs of a single linkage group and had no match with other groups (indicated by dark blue text). However, some scaffolds matched to more than one linkage group (highlighted in light blue text color and #). Blue boxes represent the approximate size of the matching scaffolds

Discussion

Genome-wide recombination rates in social Hymenoptera are among the highest known in the Metazoa, but the molecular and evolutionary causes for this phenomenon remain unclear. Here, we present an additional case of high recombination in the highly social stingless bee Frieseomelitta varia, representing the diverse and important tribe Meliponini. This result represents a significant expansion of the correlation between advanced sociality and elevated recombination rates because stingless bees have diverged from honey bees over 80 million years ago [42, 47]. In addition to its taxonomic relevance, F. varia is significant because it exhibits monandry and completely sterile workers [50, 51], in contrast to all other social insects studied for recombination rates so far. The independently assembled genome of F. varia [55] allowed us to assess genome coverage of our linkage map to further refine the recombination estimate. However, both available assemblies were highly fragmented (Our assembly: Scaffolds = 102,310 and N50 = 4687; Fvar_v1.2 assembly: Scaffolds = 2173 and N50 = 470,005) and therefore deemed insufficient for meaningful analyses of genomic correlates of local recombination rates, as in species with higher-quality genomic resources [23, 31, 33].

The 19 linkage groups of our linkage map did not match the haploid chromosome number of 15 [56]. This difference could result from a lack of high-quality markers in certain genomic regions in our study, leading to incomplete genome coverage. Alternatively, the cytological determination of the number of chromosomes could be incomplete because small chromosomes can be easily missed in species with numerous chromosomes. A recent discovery of haploid number of 17 in another Frieseomelitta species supports this notion [57]. However, six of our linkage groups are smaller than the theoretical lower size limit of 100 cM (corresponding to one obligate crossover), which suggests that our linkage map is truly unsaturated. Given that over six-thousand markers were included in our analysis, this conclusion is surprising, but a systematic lack of sequencing results in AT-rich regions [58] could be responsible. The unsaturated map underestimates the actual genetic length by at least 120 cM (considering 30 cM depicts non-linkage between two groups, and we have potentially 4 excess groups). A corresponding adjustment increases the total genetic length of our linkage map to 2678 cM, resulting in a recombination estimate of 9.73 cM/Mbp.

The interpretation that our map is unsaturated is further supported by the comparison with the published genome “F_var1.2” [55]. However, each genomic scaffold that is not covered by our linkage map could be located in-between markers or represent true coverage gaps. Our markers cover about 25 % of the scaffolds and 74 % of the genome sequence. The missing scaffolds were generally shorter than the ones covered by our markers, indicating that these smaller scaffolds could indeed be located in the intervals between markers mapping to adjacent larger scaffolds. However, about 15 % of missing scaffolds were larger than 100 kbp, and these are less likely to be located within the existing linkage groups. As an upper estimate, we thus used the missing 25 % coverage of the sequenced genome to correct our total linkage map length and consequently genome-wide recombination estimate to 12.5 cM/Mbp.

Most of the mapped scaffolds correspond to unique linkage groups. However, 112 scaffolds were not unambiguously mapped to one linkage group due to conflicting nBLAST matches for their markers. This discrepancy between our linkage map and Fvar_v1.2 genome assembly may be due to inaccurate linkage mapping, nBLAST ambiguity due to sequence similarities of different genome locations, or problems in the genome assembly. Further discrepancies between the linkage map and the physical marker location were identified with respect to local marker order in a few scaffolds. Local marker ordering for linkage map construction can be error-prone when missing genotypes are incorporated. Our very stringent data exclusion standards have minimized the problem due to missing data but diminished our sample size and thus statistical power to infer the correct local marker order. This interpretation is supported by our finding that 222 markers belonging to different genome scaffolds were not separated by any recombination event in our data. With increasing sample size, the physical distance would eventually translate into a certain, although potentially small, recombination fraction. For our genome-wide recombination estimate, this sampling problem represents a conservative error, and the estimate might have to be further corrected upwards.

The number of chromosomes can itself impact genome-wide recombination rate, and the association between chromosome number and sociality has been tested with mixed results [35, 38]. With at least 15 chromosomes, F. varia has a high number of chromosomes, and this contributes to a high genome-wide recombination rate if we assume at least one recombination event per chromosome. However, most linkage groups exceeded the corresponding value of 100 cM, and the smaller groups likely have to be combined. The recombination rate estimates of our linkage groups were decreasing with the physical length of the corresponding genome sequence. However, this negative trend was not significant. Thus, the theoretically predicted relation may not exist in F. varia, particularly considering that some of the smaller linkage groups may, in fact represent fractions of large chromosomes. The absence of a negative relation between chromosome size and recombination rate has also been observed in Apis mellifera [17, 33] and maybe another indication for selection of recombination in excess of the structurally required minimum.

Although the evolutionary conservation of extremely high recombination rates in the honey bee genus was established previously [22], based on our results, we cannot exclude the possibility that significantly elevated recombination rates may have originated before the evolution of honey bees and been evolutionarily conserved since the divergence of stingless bees, bumble bees and honey bees (Fig. 3) about 80 million years ago [59]. The recombination rates of orchid bees (Euglossini), the solitary sister taxon of honey bees [60], is unknown. A high recombination rates of orchid bees would strengthen an ancestral origin of high recombination. In contrast, low recombination rates in the Euglossini, as predicted based on the solitary lifestyle, could indicate an evolutionary reduction of recombination rates in this taxon or multiple independent origins of elevated recombination rates in honey bees, bumble bees and stingless bees in accordance with eusociality [60].

Recombination rate evolution in Hymenoptera. Recombination rates in the solitary outgroup (Drosophila melanogaster (1.6 cM/Mb), as well as solitary Hymenoptera Nasonia spp (1.5 cM/Mb), Habrobracon hebetor (4.8 cM/Mb), and Megachile rotundata (1.0 cM/Mb) are generally low, while advanced eusocial species always exhibit higher estimates, including the newly studied stingless bee Frieseomellita varia (12.5 cM/Mb). However, estimates in honey bees remain particularly high (Apis florea: 20.8 cM/Mb, A. mellifera: 21.6 cM/Mb, A. cerana: 17.4 cM/Mb, and Apis dorsata: 25.1 cM/Mb), even when compared to other eusocial Hymenoptera, including ants (Acromyrmex echinatior: 6.4 cM/Mb and Pogonomyrmex rugosus: 14.0 cM/Mb), Bumble bees (Bombus terrestris: 8.9 cM/Mb), and wasps (Vespula vulgaris: 9.7 cM/Mb). The horizontal axis depicts approximate time, illustrating divergence between species. Recombination rate data sources: [18,19,20,21,22,23, 34, 40, 61, 62]. The tips of the tree are colored according to recombination rate estimates. ML ancestral states at each node are estimated by fastAnc() function of Phytools and colored on the same gradient [63]

Compared to honey bees, our recombination rate estimates for F. varia are lower, regardless of species and methodology [17, 21, 22, 33, 34]. This finding contrasts with the prediction of a higher rate in F. varia, based on either its monandry or its social complexity. Our results do not support the view that high recombination compensates for monandry, which reduces genetic diversity compared to polyandry. Thus, our results do not support genetic diversity arguments for the evolution of high recombination in social insects. Similarly, the stronger caste divergence of F. varia compared to honey bees [50] and a specialized soldier caste [64] do not coincide with a higher recombination rate, as predicted by our second hypothesis. In contrast, the high recombination rates of Apis and the less elevated rates of F. varia and other social Hymenoptera may provide some support for the “reduced genetic conflict” hypothesis: Selection for homogenizing genetic relatedness [36] and against selfish genetic elements [37] is stronger in polyandrous than monandrous species [65], and honey bees exhibit not only exceptional recombination rates, but also an exceptional degree of polyandry [66]. The absence of ovaries in workers of F. varia is an additional factor that might reduce intra-colonial conflict compared to honey bees [50].

Conclusions

Our genome-wide recombination rate estimate of 9.3–12.5 cM/Mb for the stingless bee Frieseomelitta varia adds an important case study to the growing list of social insect species that exhibit more frequent meiotic recombination than their non-social counterparts. F. varia represents an independent taxon and indicates that elevated recombination rates in social insects are consistent, even though this species differs from previously studied social insects in regards to important life-history variables. Our study thus corroborates the association between high recombination rates and sociality in the Hymenoptera, although more comprehensive tests across many social taxa need to be performed, and our understanding of the proximate and ultimate causation of this association remains incomplete.

This study presented the the genomic recombination rate of a representative species of the important, highly social taxon Meliponini. With an estimate between 9.3 and 12.5 cM/Mb, we corroborate the association between high recombination rates and sociality in the Hymenoptera. This result strengthens the argument that advanced social evolution in social hymenopterans selects for high genomic recombination rates. Contrasting our new estimate to the consistently higher values of honey bees highlights the need for more empirical and theoretical work on the evolution of recombination in social insects.

Methods

Sampling, DNA extraction, and Sequencing

Frieseomellita varia (Lepeletier) haploid males from a single mother were obtained from one colony from the southeast region of Brazil (Departamento de Genética Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto, geographical coordinates: 21°10’12.2"S 47°51’34.2"W) between November 2018 and January 2019. The specimens were collected within the colony, kept in a glass vial on ice for about 5 min. Sex determination was based on presence of sexually dimorphic characters and gonads with the aid of a stereo microscope. To ensure that all offspring came from a single mother, the queen of the colony was color marked on the thorax (Posca Posta Pens, Japan) at the beginning of the experiment. During the collection period, no replacement of the queen was observed. Total genomic DNA was extracted from the whole body of 180 collected male offspring using the Wizard Genomic DNA Purification protocol (Promega, Dübendorf, Switzerland). The purity and concentration of extracted DNA were measured using a NanoDrop™ 1000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE). Furthermore, DNA integrity was assessed by visually inspecting samples after gel electrophoresis (1.5 % agarose, 1X SB Buffer).

From each sample, 200 ng of DNA was sent to the SNPsaurus™ sequencing facility (Eugene, Oregon) for SNP genotyping by whole-genome resequencing. In short, genomic DNA was converted to Illumina sequencing libraries with a partial Nextera DNA Flex™ reaction (SNPsaurus, Eugene, OR) and sequenced on a NovaSeq 6000 S4™ (Illumina Inc, San Diego, CA) lane with paired-end 150 bp reads. Sequence reads were quality filtered, and adaptors trimmed with bbduk (BBtools, Bushnell B. – sourceforge.net/projects/bbmap) using trim parameters: ktrim = r k = 17 hdist = 1 mink = 8 minlen = 100 qtrim = rtrimq = 10pigz = t unpigz = t ordered = t. The trimmed reads from two samples, FV116 and FV89, were combined to create a draft genome assembly with abyss-pe [67] with default parameters. Reads from each sample were aligned to this draft assembly using bbmap (BBtools) using alignment parameters: minid = 0.95 ambig = toss k = 13 idtag maxindel = 30 | samtools view -bSu - | samtools sort -@64 –o sort_file. The aligned reads were converted to a VCF format genotype using callvariants (BBtools) using callvariant parameters: ploidy = 2 multisample = t nopassdot = f minavgmapq = 15 minreadmapq = 15 strandedcov = t. Variants that were identified and their surrounding 150 bp sequence were used as our SNP markers for linkage mapping as described below.

SNP Filtering and Linkage mapping

The VCF file containing high-quality SNPs and Indels was filtered before linkage map construction based on the following criteria using VCFTools [68]: all SNPs with > 50 % missing data were removed (--max-missing 0.5); SNPs with a quality score < 30 were filtered out (--minQ 30); SNPs with a minor allele count of 3 or less were removed (--mac 3); and SNPs with a read depth of < 6 were excluded (--minDP 6). All VCFTools filtering command lines can be found in the supplementary methods (File S1). Subsequently, the 76 individuals with the least missing data (< 2 %) were chosen to generate a linkage map. Initial grouping at LOD 8 resulted in 32 linkage groups. 106 markers that were unlinked or linked to only one other marker were discarded. A total of 9404 SNPs was left after this filtering step. The markers with more than one missing data point in this refined dataset were excluded in a final filtering step, leaving 3556 SNP markers for final linkage map construction.

The 3556 SNP markers were duplicated, and the doubled set was assigned the opposite phase for mapping ‘Phase unknown’ [18]. SNPs were imported into RStudio v1.2.1335 [69] and analyzed with the RQTL package using Haldane mapping function [70]. Linkage groups were formed using formLinkageGroups() based on a minimum LOD of 5 and a maximum recombination fraction of 0.3. Since markers were present in both phases, two symmetrical sets of linkage groups were generated as expected. After discarding one set, duplicate markers (= identical genotype information) were identified using the RQTL function - findDupMarkers() and eliminated when relating to the same SNP, leaving 1023 markers. The marker order in each linkage group was determined using the orderMarkers() command. Subsequently, all linkage groups were manually searched for gaps > 20 cM, and to fill in those gaps, the tryallpositions() function was applied using 3975 previously excluded markers. After initial linkage map construction, 394 additional markers were manually added that had earlier been filtered out as duplicates. These markers were identical in genotype to markers already in the linkage map but physically mapped to a different genomic scaffold in the Fvar_1.2 genome [55] and thus extended physical coverage. Thus, we had a total of 1417 markers in our final linkage map.

Comparison to F. varia Genome

A nucleotide BLAST (nBLAST) search [71] was performed for the sequence associated with each SNP marker in the F. varia genome assembly Fvar_v1.2 (GenBank assembly accession: GCA_011392965.1). An E-value threshold of 1e-50 was used, which returned at least one match for 1404 (of 1417 total) markers. The other markers were considered to be located in sequences that are missing from Fvar_v1.2. The best match of each sequence to a scaffold was considered for assigning scaffolds to linkage groups. When markers from different linkage groups matched the same scaffold, we assigned the scaffold to only one linkage group based on the following rules. First, scaffolds were assigned to a linkage group based on a simple majority rule when the number of matching markers differed between linkage groups. In cases with an equal number of matching markers, the synteny of linkage groups and scaffolds was considered. Still unresolved cases were decided based on the E-value of individual nBLAST matches.

Comparative visualization of recombination rates

The R package phytools [63] was used to create a visual representation of the evolution of recombination rates in the order Hymenoptera by estimating ancestral states using fastAnc() function, based on their phylogeny [60, 72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,81,83] and focusing on species with available genome-wide recombination rate estimates [18,19,20,21,22,23, 34, 40, 61, 62].

Availability of data and materials

The raw sequencing data and draft genome assembly reported in this paper have been deposited in the NCBI BioProject accession number PRJNA668370 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/?term=PRJNA668370). In-text cited supplementary data (Figure S1, Figure S2, File S1, File S2, Table S1, and Table S2), R codes/macros (File S2), and data to generate phylogeny (File S3 and File S4) can be accessed as online supplementary materials and are also available to download at Zenodo database (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4638539) .

Abbreviations

- cM:

-

Centimorgan

- SNP:

-

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- VCF:

-

Variant calling format

- nBLAST:

-

Nucleotide basic local alignment search tool

- LG:

-

Linkage group

References

Mercier R, Mézard C, Jenczewski E, Macaisne N, Grelon M. The molecular biology of meiosis in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2015;66(1):297–327.

Fernandes JB, Séguéla-Arnaud M, Larchevêque C, Lloyd AH, Mercier R. Unleashing meiotic crossovers in hybrid plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2018;115(10):2431–6.

Ritz KR, Noor MAF, Singh ND. Variation in recombination rate: adaptive or not? Trends Genet. 2017;33(5):364–74.

Hartfield M, Keightley PD. Current hypotheses for the evolution of sex and recombination. Integr Zool. 2012;7(2):192–209.

Hill WG, Robertson A. The effect of linkage on limits to artificial selection. Genet Res. 1966;8(3):269–94.

Hamilton WD, Axelrod R, Tanese R. Sexual reproduction as an adaptation to resist parasites (a review). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87(9):3566–73.

Kondrashov AS. Selection against harmful mutations in large sexual and asexual populations. Genet Res. 1982;40(3):325–32.

Capilla L, Garcia Caldés M, Ruiz-Herrera A. Mammalian meiotic recombination: a toolbox for genome evolution. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2016;150(1):1–16.

Comeron JM, Ratnappan R, Bailin S. The many landscapes of recombination in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Genet. 2012;8(10):e1002905. Petrov DA, editor

Hunter CM, Huang W, Mackay TFC, Singh ND. The genetic architecture of natural variation in recombination rate in Drosophila melanogaster. PLOS Genet. 2016;12(4):e1005951. Sekelsky J, editor

Kawakami T, Mugal CF, Suh A, Nater A, Burri R, Smeds L, et al. Whole-genome patterns of linkage disequilibrium across flycatcher populations clarify the causes and consequences of fine-scale recombination rate variation in birds. Mol Ecol. 2017;26(16):4158–72.

Stapley J, Feulner PGD, Johnston SE, Santure AW, Smadja CM. Variation in recombination frequency and distribution across eukaryotes: patterns and processes. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci. 2017;372(1736):20160455.

Becks L, Agrawal AF. Higher rates of sex evolve in spatially heterogeneous environments. Nature. 2010;468(7320):89–92.

Carja O, Liberman U, Feldman MW. Evolution in changing environments: modifiers of mutation, recombination, and migration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(50):17935–40.

Ross-Ibarra J. The evolution of recombination under domestication: a test of two hypotheses. Am Nat. 2004;163(1):105–12.

Smukowski CS, Noor M, a. F. Recombination rate variation in closely related species. Heredity. 2011;107(6):496–508.

Beye M, Gattermeier I, Hasselmann M, Gempe T, Schioett M, Baines JF, et al. Exceptionally high levels of recombination across the honey bee genome. Genome Res. 2006;16(11):1339–44.

Sirvio A, Gadau J, Rueppell O, Lamatsch D, Boomsma JJ, Pamilo P, et al. High recombination frequency creates genotypic diversity in colonies of the leaf-cutting ant Acromyrmex echinatior. J Evol Biol. 2006;19(5):1475–85.

Wilfert L, Gadau J, Schmid-Hempel P. Variation in genomic recombination rates among animal taxa and the case of social insects. Heredity. 2007;98(4):189–97.

Sirviö A, Johnston JS, Wenseleers T, Pamilo P. A high recombination rate in eusocial Hymenoptera: evidence from the common wasp Vespula vulgaris. BMC Genet. 2011;12(1):95.

Shi YY, Sun LX, Huang ZY, Wu XB, Zhu YQ, Zheng HJ, et al. A SNP based high-density linkage map of apis cerana reveals a high recombination rate similar to apis mellifera. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(10):e76459. Mittapalli O, editor

Rueppell O, Kuster R, Miller K, Fouks B, Rubio Correa S, Collazo J, et al. A New Metazoan Recombination Rate Record and Consistently High Recombination Rates in the Honey Bee Genus Apis Accompanied by Frequent Inversions but Not Translocations. Genome Biol Evol. 2016;8(12):3653–60.

Jones JC, Wallberg A, Christmas MJ, Kapheim KM, Webster MT. Extreme differences in recombination rate between the genomes of a solitary and a social bee. Mol Biol Evol. 2019;36(10):2277–91 Singh N, editor.

Crespi BJ, Yanega D. The definition of eusociality. Behav Ecol. 1995;6(1):109–15.

Choe JC, Crespi BJ. The evolution of social behavior in insects and arachnids. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1997.

Stolle E, Wilfert L, Schmid-Hempel R, Schmid-Hempel P, Kube M, Reinhardt R, et al. A second generation genetic map of the bumblebee Bombus terrestris (Linnaeus, 1758) reveals slow genome and chromosome evolution in the Apidae. BMC Genomics. 2011;12(1):48.

Crozier RH, Fjerdingstad EJ. Polyandry in social Hymenoptera—disunity in diversity? In: Annales Zoologici Fennici. Finnish Zoological and Botanical Publishing Board. 2001;38:267–85.

Mattila HR, Seeley TD. Genetic diversity in honey bee colonies enhances productivity and fitness. Science. 2007;317(5836):362–4.

Tarpy DR, Seeley TD. Lower disease infections in honeybee (Apis mellifera) colonies headed by polyandrous vs monandrous queens. Naturwissenschaften. 2006;93(4):195–9.

Rueppell O, Meier S, Deutsch R. Multiple mating but not recombination causes quantitative increase in offspring genetic diversity for varying genetic architectures. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(10):e47220. Salamin N, editor

Kent CF, Minaei S, Harpur BA, Zayed A. Recombination is associated with the evolution of genome structure and worker behavior in honey bees. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109(44):18012–7.

Kent CF, Zayed A. Evolution of recombination and genome structure in eusocial insects. Commun Integr Biol. 2013;6(2):e22919.

Liu H, Zhang X, Huang J, Chen J-Q, Tian D, Hurst LD, et al. Causes and consequences of crossing-over evidenced via a high-resolution recombinational landscape of the honey bee. Genome Biol. 2015;16(1):15.

Wallberg A, Glémin S, Webster MT. Extreme recombination frequencies shape genome variation and evolution in the honeybee, Apis mellifera. PLoS Genet. 2015;11(4):e1005189.

Sherman PW. Insect chromosome numbers and eusociality. Am Nat. 1979;113(6):925–35.

Templeton AR. Chromosome number, quantitative genetics and eusociality. Am Nat. 1979;113(6):937–41.

Haig D, Grafen A. Genetic scrambling as a defence against meiotic drive. J Theor Biol. 1991;153(4):531–58.

Ross L, Blackmon H, Lorite P, Gokhman VE, Hardy NB. Recombination, chromosome number and eusociality in the Hymenoptera. J Evol Biol. 2015;28(1):105–16.

Wang J, Wurm Y, Nipitwattanaphon M, Riba-Grognuz O, Huang Y-C, Shoemaker D, et al. A Y-like social chromosome causes alternative colony organization in fire ants. Nature. 2013;493(7434):664–8.

Sirviö A, Pamilo P, Johnson RA, Page RE Jr., Gadau J. Origin and evolution of the dependent lineages in the genetic caste determination system of pogonomyrmex ants: origin and evolution of the dependent lineages. Evolution. 2011;65(3):869–84.

Hughes WOH, Oldroyd BP, Beekman M, Ratnieks FLW. Ancestral monogamy shows kin selection is key to the evolution of eusociality. Science. 2008;320(5880):1213–6.

Danforth BN, Cardinal S, Praz C, Almeida EAB, Michez D. The impact of molecular data on our understanding of bee phylogeny and evolution. Annu Rev Entomol. 2013;7(1):57–78.

Michener CD. The Meliponini. In: Vit P, Pedro SRM, Roubik D, editors. Pot-Honey. New York: Springer New York; 2013. p. 3–17. Available from: http://link.springer.com/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-4960-7_1 [cited 19 Sep 2020]

de Camargo JMF, de Menezes Pedro SR. Systematics, phylogeny and biogeography of the Meliponinae (Hymenoptera, Apidae): a mini-review. Apidologie. 1992;23(6):509–22.

Rasmussen C, Cameron SA. Global stingless bee phylogeny supports ancient divergence, vicariance, and long distance dispersal. Biol J Linn Soc. 2010;99(1):206–32.

Hrncir M, Jarau S, Barth FG. Stingless bees (Meliponini): senses and behavior. J Comp Physiol A. 2016;202(9–10):597–601.

Cridland JM, Tsutsui ND, Ramírez SR. The complex demographic history and evolutionary origin of the western honey bee, apis mellifera. Genome Biol Evol. 2017;9(2):457–72.

Ross CR, DeFelice DS, Hunt GJ, Ihle KE, Amdam GV, Rueppell O. Genomic correlates of recombination rate and its variability across eight recombination maps in the western honey bee (Apis mellifera L.). BMC Genomics. 2015;16(1):107.

DeLory T, Funderburk K, Miller K, Zuluaga-Smith W, McPherson S, Pirk CW, et al. Local variation in recombination rates of the honey bee (Apis mellifera) genome among samples from six disparate populations. Insectes Sociaux. 2020;67(1):127–38.

Boleli IC, Paulino-Simões ZL, Gentile Bitondi MM. Cell death in ovarioles causes permanent sterility in Frieseomelitta varia worker bees. J Morphol. 1999;242(3):271–82.

Peters JM, Queller DC, Imperatriz–Fonseca VL, Roubik DW, Strassmann JE. Mate number, kin selection and social conflicts in stingless bees and honeybees. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1999;22(1417):379–84.

Vollet-Neto A, Koffler S, dos Santos CF, Menezes C, Nunes FMF, Hartfelder K, et al. Recent advances in reproductive biology of stingless bees. Insectes Sociaux. 2018;65(2):201–12.

Luna-Lucena D, Rabico F, Simoes ZL. Reproductive capacity and castes in eusocial stingless bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Curr Opin Insect Sci. 2019;31:20–8.

Moure JS, Graf V, Urban D. Catálogo de Apoidea da região neotropical (Hymenoptera, Colletidae). I. paracolletini. Rev Bras Zool. 1999;16(suppl 1):1–46.

de Paula Freitas FC, Lourenço AP, Nunes FMF, Paschoal AR, Abreu FCP, Barbin FO, et al. The nuclear and mitochondrial genomes of Frieseomelitta varia – a highly eusocial stingless bee (Meliponini) with a permanently sterile worker caste. BMC Genomics. 2020;21(1):386.

Kerr WE, da Silveira ZV. Karyotypic evolution of bees and corresponding taxonomic implications. Evolution. 1972;26(2):197.

Nascimento RM, Carvalho AF, Santana WC, Barth A, Costa MA. Karyotype diversity of stingless bees of the genus Frieseomelitta (Hymenoptera, Apidae, Meliponini). Caryologia. Int J Cytol Cytosystematics Cytogenet. 2020;73(2):121–6.

The Honeybee Genome Sequencing Consortium. Insights into social insects from the genome of the honeybee Apis mellifera. Nature. 2006;443(7114):931–49.

Cardinal S, Straka J, Danforth BN. Comprehensive phylogeny of apid bees reveals the evolutionary origins and antiquity of cleptoparasitism. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2010;107(37):16207–11.

Woodard SH, Fischman BJ, Venkat A, Hudson ME, Varala K, Cameron SA, et al. Genes involved in convergent evolution of eusociality in bees. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;3(18):7472–7.

Kawakami T, Wallberg A, Olsson A, Wintermantel D, de Miranda JR, Allsopp M, Rundlöf M, Webster MT. Substantial heritable variation in recombination rate on multiple scales in honeybees and bumblebees. Genetics. 2019;212(4):1101–19.

Liu H, Jia Y, Sun X, Tian D, Hurst LD, Yang S. Direct determination of the mutation rate in the bumblebee reveals evidence for weak recombination-associated mutation and an approximate rate constancy in insects. Mol Biol Evol. 2017;34(1):119–30.

Revell LJ. phytools: an R package for phylogenetic comparative biology (and other things): phytools: R package. Methods Ecol Evol. 2012;3(2):217–23.

Grüter C, Segers FHID, Menezes C, Vollet-Neto A, Falcón T, von Zuben L, et al. Repeated evolution of soldier sub-castes suggests parasitism drives social complexity in stingless bees. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):4.

Galbraith DA, Kocher SD, Glenn T, Albert I, Hunt GJ, Strassmann JE, et al. Testing the kinship theory of intragenomic conflict in honey bees (Apis mellifera). Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2016;113(4):1020–5.

Tarpy DR, Nielsen DI. Sampling error, effective paternity, and estimating the genetic structure of honey bee colonies (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Ann Entomol Soc Am. 2002;95(4):513–28.

Jackman SD, Vandervalk BP, Mohamadi H, Chu J, Yeo S, Hammond SA, et al. ABySS 2.0: resource-efficient assembly of large genomes using a Bloom filter. Genome Res. 2017;27(5):768–77.

Danecek P, Auton A, Abecasis G, Albers CA, Banks E, DePristo MA, et al. The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(15):2156–8.

RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R. Boston: RStudio, PBC; 2020. Available from: http://www.rstudio.com/

Broman KW, Wu H, Sen S, Churchill GA. R/qtl: QTL mapping in experimental crosses. Bioinformatics. 2003;19(7):889–90.

Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215(3):403–10.

Brady SG, Schultz TR, Fisher BL, Ward PS. Evaluating alternative hypotheses for the early evolution and diversification of ants. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2006;103(48):18172–7.

Cardinal S, Danforth BN. The antiquity and evolutionary history of social behavior in bees. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(6):e21086. Moreau CS, editor.

Engel MS. Fossil honey bees and evolution in the genus Apis (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Apidologie. 1998;29(3):265–81.

Fath-Goodin A, Webb BA. Polydnaviruses: General Features. In: Encyclopedia of Virology. Elsevier; 2008. p. 256–61. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/B9780123744104004726 [cited 25 Dec 2020]

Garnery L, Vautrin D, Cornuet JM, Solignac M. Phylogenetic relationships in the genus Apis inferred from mitochondrial DNA sequence data. Apidologie. 1991;22(1):87–92.

Hasselmann M, Vekemans X, Pflugfelder J, Koeniger N, Koeniger G, Tingek S, et al. Evidence for convergent nucleotide evolution and high allelic turnover rates at the complementary sex determiner gene of western and Asian honeybees. Mol Biol Evol. 2008;25(4):696–708.

Litman JR, Danforth BN, Eardley CD, Praz CJ. Why do leafcutter bees cut leaves? New insights into the early evolution of bees. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2011;278(1724):3593–600.

Misof B, Liu S, Meusemann K, Peters RS, Donath A, Mayer C, et al. Phylogenomics resolves the timing and pattern of insect evolution. Science. 2014;346(6210):763–7.

Park J, Peng Z, Zeng J, Elango N, Park T, Wheeler D, et al. Comparative analyses of DNA methylation and sequence evolution using Nasonia genomes. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28(12):3345–54.

Peters RS, Krogmann L, Mayer C, Donath A, Gunkel S, Meusemann K, et al. Evolutionary History of the Hymenoptera. Curr Biol. 2017;27(7):1013–8.

Travenzoli NM, Cardoso DC, de Werneck HA, Fernandes-Salomão TM, Tavares MG, Lopes DM. The evolution of haploid chromosome numbers in Meliponini. PLOS ONE. 2019;14(10):e0224463 De la Rúa P, editor.

Wenseleers T, van Zweden JS. Sensory and cognitive adaptations to social living in insect societies. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2017;114(25):6424–6.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Cristian Hernandez (University of North Carolina at Greensboro) for assistance in data cleaning as an undergraduate researcher and Eric Johnson (SNPsaurus Inc, Eugene, OR) for support with raw data interpretation and the draft genome assembly. A part of our computations was performed at the ITS Research Computing facility (https://its.unc.edu/research-computing/longleaf-cluster/) of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Funding

The research was supported by the São Paulo State Research Foundation, FAPESP, Process number 16/06657-0, UNCG’s Florence Schaeffer Endowment and UNC Greensboro.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

OR and ZLPS conceived and supervised the project, DLL collected the samples and identified the sex of the specimens. FCPA and DLL extracted the DNA for sequencing. PW performed the linkage analyses and made figures and tables. OR advised and interpreted the results. FF contributed with access to F. varia genome first draft. PW and OR wrote the draft and revisions of this manuscript. All authors read, contributed to and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not Applicable.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Alignment of all linkage groups markers to F. varia genome assembly (F_var1.2).

Additional file 2: Figure S2.

Relation between physical size and recombination rates of linkage groups.

Additional file 3. File S1.

R-codes, macros, and terminal command lines used in this study.

Additional file 4: File S2.

R-Codes, macros, and terminal command lines used in this study. Annotated text file that describe all the codes used at different analyses performed in this genetic map study.

Additional file 5: File S3.

Divergence time data for phylogenetic tree. Newick tree format file containing approximate divergence time between species. All the data is obtained from references cited in Fig. 3 legend.

Additional file 6: File S4.

Recombination rate data for phylogenetic tree. Recombination rate data used in phylogenetic tree. All the data is obtained from references cited in Fig. 3 legend.

Additional file 7: Table S1.

Summary statistics of sequenced reads. The text file shows high-quality read counts for each male bee sample, % alignment to the reference, and proportion of the genotypes.

Additional file 8: Table S2.

Sequence alignment output of markers to the genome assembly. BLAST output of mapped SNPs (with linkage group placement info) against F. varia genome assembly (F_var1.2).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Waiker, P., de Abreu, F.C.P., Luna-Lucena, D. et al. Recombination mapping of the Brazilian stingless bee Frieseomelitta varia confirms high recombination rates in social hymenoptera. BMC Genomics 22, 673 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-021-07987-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-021-07987-3