Abstract

Background

Crustacea, the second largest subphylum of Arthropoda, includes species of major ecological and economic importance, such as crabs, lobsters, crayfishes, shrimps, and barnacles. With the rapid development of crustacean aquaculture and biodiversity loss, understanding the gene regulatory mechanisms of growth, reproduction, and development of crustaceans is crucial to both aquaculture development and biodiversity conservation of this group of organisms. In these biological processes, transcription factors (TFs) play a vital role in regulating gene expression. However, crustacean transcription factors are still largely unknown, because the lack of complete genome sequences of most crustacean species hampers the studies on their transcriptional regulation on a system-wide scale. Thus, the current TF databases derived from genome sequences contain TF information for only a few crustacean species and are insufficient to elucidate the transcriptional diversity of such a large animal group.

Results

Our database CrusTF (http://qinlab.sls.cuhk.edu.hk/CrusTF) provides comprehensive information for evolutionary and functional studies on the crustacean transcriptional regulatory system. CrusTF fills the knowledge gap of transcriptional regulation in crustaceans by exploring publicly available and newly sequenced transcriptomes of 170 crustacean species and identifying 131,941 TFs within 63 TF families. CrusTF features three categories of information: sequence, function, and evolution of crustacean TFs. The database enables searching, browsing and downloading of crustacean TF sequences. CrusTF infers DNA binding motifs of crustacean TFs, thus facilitating the users to predict potential downstream TF targets. The database also presents evolutionary analyses of crustacean TFs, which improve our understanding of the evolution of transcriptional regulatory systems in crustaceans.

Conclusions

Given the importance of TF information in evolutionary and functional studies on transcriptional regulatory systems of crustaceans, this database will constitute a key resource for the research community of crustacean biology and evolutionary biology. Moreover, CrusTF serves as a model for the construction of TF database derived from transcriptome data. A similar approach could be applied to other groups of organisms, for which transcriptomes are more readily available than genomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Transcription factors (TFs), regulators of gene transcription, are critical for most if not all biological processes. They possess DNA-binding domains (DBDs) that can recognize specific DNA sequences to mediate the TF-DNA interaction. By binding to functional DNA elements, such as promoter, enhancer, silencer, and insulator, TFs can activate or suppress the transcription of their target genes and precisely control the cell phenotypes and functions. The TF repertoires of many species throughout the tree of life have been available in several TF databases, most of which identify TFs from genome sequences. For example, DBD (transcription factor prediction database) predicts TFs from 930 completely sequenced genomes, in Archaea, Bacteria, and Eukaryota [1]. CIS-BP (Catalog of Inferred Sequence Binding Preferences) covering 290 eukaryotic genomes accrue DNA binding motifs based on the experimental identification and computational inference [2]. Other TF databases that focus on specific taxonomic groups are also mainly based on genome sequences. For instance, AnimalTFDB recorded TFs from 65 animals, mostly vertebrates [3], while FlyFactorSurvey [4] and FactorBook [5] focus on the binding specificity of TFs of fruit fly, human, and mouse. However, as only a few crustacean genomes have been sequenced to date, among the mentioned TF databases, only CIS-BP covers two crustacean species, while DBD contains one. Consequently, critical knowledge concerning crustacean TFs, including their sequences, functions and evolution, have been rarely explored.

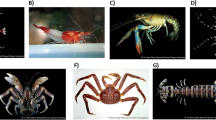

Crustaceans are a diverse group of animals of ecological and commercial importance all over the world; including many species of high economic values in fisheries and aquaculture, particularly the decapods such as crabs (Brachyura), lobsters (Astacidea and Achelata), crayfishes (Astacidea) and shrimps (Caridea and Dendrobranchiata). The total production of crustacean farming in 2015 has increased to nearly 14 million tons, with an average annual increase rate of 3.75% in recent years [6]. About half of all crustacean products are produced by aquaculture, and the other half relies on capture fishery [6]. The proportion of crustaceans among all aquaculture animals has increased from less than 5% before 2000 to close to 10% in 2015, valued at over US$38 billion [7]. The escalating harvest of wild stocks of commercially important decapod crustaceans for fishery and aquaculture has also incited public concern about the sustainability and the detrimental environmental impact of such practice. A few studies have already documented the negative effects of crustacean fishery and aquaculture on the environment and crustacean biodiversity [8, 9]. Besides the economic species, many small crustacean species are important components in various ecosystems. Many of them, for instance, the krill (Euphausiacea) and copepods (Copepoda), are a major food resource for many marine faunae, serving as important trophic links between the primary producers and the macrofauna [10]. Others, such as amphipods (Amphipoda) and Daphnia (Cladocera), are often used as bioindicators to assess the impact of human activity and environmental changes on ecosystems and biodiversity [11,12,13]. Research on the growth, reproduction, and development of crustaceans is particularly crucial to fisheries, aquaculture, biodiversity conservation and environmental protection. Given the importance of TFs in these biological processes, investigations on crustacean TFs become urgent for the improvement of crustacean fisheries and aquaculture, and mitigation of biodiversity degradation and loss.

Our current knowledge on crustacean TFs is mainly derived from low-throughput experiments, and restricted to only a few TFs in a few species [14,15,16,17]. A system-wide exploration on the repertoire of crustacean TFs will shed light on the complexity and diversity of crustacean transcriptional regulatory systems. Fortunately, despite the lack of genome sequence for most crustacean species, a large repertoire of transcriptomes of many crustacean species emerged in recent years provides us the opportunity to predict TFs from assembled transcripts on a transcriptome-wide scale. We collected the publicly available and newly sequenced crustacean transcriptomes in our laboratory and searched all TFs in the transcriptome assemblies. To disseminate our results, we constructed a database CrusTF, in which coding sequences (CDSs), protein sequences, DBDs, DNA binding motifs and phylogeny of crustacean TFs could be freely accessed by researchers. Compared to current TF databases containing only a few crustaceans, CrusTF includes TFs from 170 crustacean species. It is the first TF database derived from transcriptome data. It will serve as a model to fill the knowledge gap of TF genes throughout the tree of life for those species of which transcriptomes are more readily available than genomes.

Construction and content

CrusTF is a database of crustacean TFs mainly derived from de novo transcriptome assemblies. It has explored a comprehensive collection of crustacean transcriptomes to identify transcribed crustacean TFs. It allows users to search TFs with keywords matching TF names or TF identifiers, to select species and TF family of interest, or to search by Blast tools with their own TF sequences. Free batch download is available for the TF CDSs, protein sequences and domain sequences of selected species or TF families. Besides TF sequences, CrusTF also contains functional and evolutionary information of crustacean TFs.

Database implementation

CrusTF implements a Linux-Apache-MySQL-PHP (LAMP) system. All data were saved in MySQL database, including TF sequences, TF information, domains, species information, and motifs. The web is constructed based on CodeIgniter, a powerful PHP framework. CodeIgniter provides an Application Programming Interface (API) to connect the web to MySQL database. We also used JavaScript libraries including jQuery (2.2.0), jQuery-labelauty and some additional plugins to perform dynamic web services.

Data resources

Crustacean transcriptomes were downloaded from two public databases, National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Transcriptome Shotgun Assembly (TSA) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/tsa/) and Short Read Archive (SRA) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra). The detailed information of all transcriptomes from SRA and TSA is summarized in Additional file 1: Tables S2 and S3, respectively. As of January 2017, our transcriptome collection composes of 919 and 122 crustacean transcriptome samples curated from SRA and TSA databases, respectively (Additional file 1: Tables S2 and S3). 37 RNA-seq samples of 31 crustacean species generated in our laboratory were also included in the current version of CrusTF (Additional file 1: Table S1 and unpublished data of Ma et al.). Additional file 1: Table S1 lists the transcriptome data sources of each crustacean species available in CrusTF. Besides, crustacean genes, including those derived from low-throughput experiments, were downloaded from GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/) (Additional file 1: Table S4).

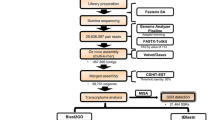

Data processing

For transcriptomes in TSA, assembled contigs were directly downloaded from the database. For transcriptome data in SRA, raw reads of RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) were downloaded. To standardize the data processing procedure, only RNA-seq data generated using Illumina sequencers were selected. Quality of raw reads was assessed by FastQC (https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/). Adapters were trimmed by Trimmomatic [18], allowing two seed mismatches to tolerate sequencing errors in adapter sequences. Subsequences of reads with low quality (average quality score lower than 20) were removed. Trimmed reads shorter than 50 nucleotides were also deleted. Processed raw reads were assembled de novo using Trinity version 2.4.0 with the default setting to obtain contigs of transcript sequences [19]. Potentially contaminated sequences from bacteria, virus or archaea were filtered by Kraken [20]. Contigs from multiple transcriptomes of the same species are clustered and further assembled by TGICL with an identity cutoff of 0.94 to reduce redundancy [21]. CDSs and amino acid sequences were deduced from assembled contigs, as well as sequences from GenBank, with Transdecoder [22].

Functional annotation of TFs

DNA binding domains (DBDs) were identified by scanning all crustacean proteins with HMMs of known DBDs from Pfam database [23] by PfamScan that implements HMMER3 [24]. Predicted TFs with DBDs were compared to known TFs well annotated in CIS-BP and named by the best matched known TFs.

DNA binding motif of each TF was inferred as described previously [2]. In brief, DBDs of crustacean TFs were compared with those of TFs with known binding motifs, and similarity between crustacean TFs and known TFs was calculated. Based on the observation on co-evolution of DBD sequences and their DNA binding motifs, it has been reported that the TF binding motifs of a TF could be inferred from those of homologous TF DBDs when the identity between the two DBDs is greater than a threshold [2]. The thresholds of all TF families could be found in CIS-BP (file cisbp_1.02.tf_families.sql in the package from “Download MySQL Tables” in http://cisbp.ccbr.utoronto.ca/bulk.php). Known TF binding motifs of metazoan TFs were downloaded from CIS-BP [2], JASPAR [25], UniPROBE [26] and hPDI [27]. DNA binding motif of crustacean TFs could be inferred when their DBDs were highly similar to TFs with DNA binding motifs that have been detected experimentally.

The confidence level of a predicted TF was estimated using several criteria: 1) the percentage of the top hit that matches the predicted TF, E-value, Blast score and sequence identity when Blast to the protein database SwissProt, 2) the bit-score and E-value of PfamScan, 3) the number of homologs found in other crustacean species, 4) the number of transcriptome samples from which the TF was detected. Crustacean TFs of each family were ranked according to the Blast E-value, PfamScan E-value, the number of crustacean homologs and the number of supported samples, respectively. The TFs were ranked according to the four criteria. The ranks of each TF imply the confidence of the predicted TF.

Evolutionary analysis

The DBD sequences of the crustacean TFs and TFs of 117 other animals in each TF family were aligned with Clustal Omega, which is a fast and scalable tool for multiple amino acid sequence alignment [28]. Approximately-maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree of each TF family was reconstructed with FastTree with JTT + CAT model [29]. Trees were visualized by R package ggtree [30] and iTOL (Interactive Tree Of Life) [31]. Users can manipulate the trees interactively via iTOL.

Utility and discussion

The crustacean TFs in CrusTF are classified according to the species and functional domain types. Users can choose a species of interest from the species list to browse all crustacean TFs identified from its transcriptomes. In the current version, CrusTF has a total of 170 crustacean species (Table 1), of which only two species (Daphnia pulex and Artemia franciscana) are included in other TF databases (DBD and CIS-BP) based on genome sequences. Our collection covers 15 crustacean orders (Fig. 1a). Two major orders are Decapoda and Amphipoda, which have 68 and 70 species in our collection, respectively. The former is the order containing many economic crustacean species, like crabs, lobsters, crayfishes, and shrimps (http://www.fao.org/fishery/collection/asfis/en), while the latter contains many species for environmental monitoring [32]. Even though other orders only have 1 to 5 species, they are usually the most representative species in those orders. The high coverage of species in this subphylum allows the direct comparison of TF sequences among different crustaceans. So CrusTF provides the function of searching similar TFs in other species for each TF. Homolog search against crustacean TFs from transcriptomes, GenBank, and TFs from genomes of other animals could be easily achieved by click on the “Search” buttons in the main page of each TF. Users can investigate how homologous TFs are changed among different species.

Statistics of CrusTF. a Number of species belonging to 15 orders of Crustacea. b Increase in the number of crustacean species of which transcriptomes or genomes have been published. All four databases belong to National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). SRA Transcriptome: Transcriptomes (RNA-seq) in Short Read Archive; TSA: Transcriptome Shotgun Assembly database; NCBI Genome: NCBI genome database; WGS: Whole Genome Shotgun database. c Number of TFs identified in each species

When compared to the number of available crustacean genomes, the number of crustacean species with transcriptome data grows much faster in recent years (Fig. 1b). Thus, identification of TFs from de novo assembled transcriptomes would be a much more efficient approach for species without available genomes and an important supplement to the current methods based on whole genome sequences. However, as shown in Table 1, since the data volumes for different species vary, the coverage of transcriptomes may be quite different among species. The number of total unique contigs varies from 1102 to 641,047, due to the variations of library preparation methods, sequencing throughput and the number of samples. Therefore, the number of TFs predicted from different species ranges from 6 to 10,535 (Fig. 1c). This is because of the limitations of the transcriptomic approach. First, transcriptomes are usually incomplete when the sequencing throughput is low or the RNA samples used cannot cover a wide range of different tissues and conditions. When a gene is not expressed in the sampled conditions, it would not be sequenced. Thus, these species have less predicted TFs. Secondly, de novo assembly of transcriptome may generate many false transcripts, which could be filtered out by comparing to known genes or protein features. Yet we did not filter them out, because filtering assembled transcripts based on current knowledge may lead to loss of novel TFs that may be very important. Thus, we keep all predicted TFs and provide the information of evidence that support them (See Construction and content), from which users can easily estimate the reliability of the predicted TF and also have the opportunity to explore new TFs for further investigation. Despite its limitations, our transcriptomic approach is still an efficient and valuable way to predict TFs, especially when the genomes of many species are not available.

In the current version, CrusTF contains 131,941 and 8502 TFs of crustacean species from transcriptomes and GenBank, respectively. They are classified into 63 TF families according to the DBDs or DBD combinations detected in their sequences (Fig. 2). Detailed information of TF families are listed in and Additional file 1: Table S5. Many TF families that are prevalently detected in metazoans were detected in most crustaceans. Interestingly, crustaceans have distinct patterns of TF family composition when compared to other animals (Fig. 2). Several TFs families, such as families with Zinc finger CCCH domain and BED zinc finger, show extensive expansion in crustaceans. Some TF families with distinct DBD combinations may represent putative TFs unique to this animal group and have not been characterized in other TF databases (Fig. 2). Users can browse the TFs of a certain TF family by selecting it from the TF family list. And they can also download all TF sequences of a family from a species of interest or all crustacean species in the “Download” page.

TF families in crustaceans compared to those in other animals. Colors in the figure show the percentage of TFs in each TF family over all predicted TFs in a species (white, <1%; yellow to green, 1–100%). Each row is a species and each column is a TF family. Side bar highlights the taxa. Many TF families on the left that are prevalently detected in metazoans were detected in most crustaceans. Several TFs families, such as families with Zinc finger CCCH domain (CCCH ZF) and BED zinc finger (BED ZF), show extensive expansion in crustaceans. Some TF families with distinct DBD combinations may represent putative TFs unique to this animal group and have not been characterized in other TF databases

To facilitate the users to understand the phylogenetic relationships among crustacean DBDs and DBDs from other animals, the phylogenetic tree of each DBD type is available in the “Trees” page. These trees visualize the phylogenetic relationships among DBDs from our 170 crustaceans and 117 other animals of 9 phyla from Porifera to Chordata. Based on the phylogenetic relationships of DBDs, CrusTF has inferred the DNA binding motif for each TF from their closest TFs with motifs derived from experimental studies. Users can browse the motif information on the web page of each TF and download the motifs for further prediction of downstream targets.

Conclusion

In summary, CrusTF is the first TF database derived from transcriptome data. It uncovers the specific pattern of the transcriptional regulatory system of crustaceans and the diversity of TFs in this important group of animals. This database will constitute a key resource for the research community of crustacean biology and evolutionary biology. Given the importance of TF information in functional studies on transcriptional regulatory systems of crustaceans, it will facilitate the research works on growth, reproduction, and development of crustaceans, and subsequently benefit studies on crustacean fisheries, aquaculture, biodiversity conservation and environmental protection.

Abbreviations

- API:

-

Application programming interface

- CDS:

-

Coding sequence

- CIS-BP:

-

Catalog of inferred sequence binding preferences

- DBD:

-

DNA-binding domain

- iTOL:

-

Interactive tree of life

- LAMP:

-

Linux-Apache-MySQL-PHP system

- NCBI:

-

National Center for Biotechnology Information

- RNA-seq:

-

RNA sequencing

- SRA:

-

Short read archive

- TF:

-

Transcription factor

- TSA:

-

Transcriptome shotgun assembly database

- ZF:

-

Zinc finger

References

Charoensawan V, Wilson D, Teichmann SA. Genomic repertoires of DNA-binding transcription factors across the tree of life. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:7364–77.

Weirauch MT, Yang A, Albu M, Cote AG, Montenegro-Montero A, Drewe P, Najafabadi HS, Lambert SA, Mann I, Cook K, et al. Determination and inference of eukaryotic transcription factor sequence specificity. Cell. 2014;158:1431–43.

Zhang HM, Liu T, Liu CJ, Song S, Zhang X, Liu W, Jia H, Xue Y, Guo AY. AnimalTFDB 2.0: a resource for expression, prediction and functional study of animal transcription factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D76–81.

Zhu LJ, Christensen RG, Kazemian M, Hull CJ, Enuameh MS, Basciotta MD, Brasefield JA, Zhu C, Asriyan Y, Lapointe DS, et al. FlyFactorSurvey: a database of Drosophila transcription factor binding specificities determined using the bacterial one-hybrid system. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D111–7.

Wang J, Zhuang J, Iyer S, Lin XY, Greven MC, Kim BH, Moore J, Pierce BG, Dong X, Virgil D, et al. Factorbook.org: a wiki-based database for transcription factor-binding data generated by the ENCODE consortium. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D171–6.

FAO: Global production statistics. 2017.

Zhou X. An overview of recently published global aquaculture statistics. FAO aquaculture. Newsletter. 2017;56

Pohle G, Iken K, Clarke KR, Trott T, Konar B, Cruz-Motta JJ, Wong M, Benedetti-Cecchi L, Mead A, Miloslavich P, et al. Aspects of benthic decapod diversity and distribution from rocky nearshore habitat at geographically widely dispersed sites. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18606.

Kunsook C, Dumrongrojwatthana P. Species diversity and abundance of marine crabs (Portunidae: Decapoda) from a collapsible crab trap fishery at kung Krabaen Bay, Chanthaburi Province, Thailand. Trop Life Sci Res. 2017;28:45–67.

Atkinsona A, Siegelb V, Pakhomovc EA, Jessoppa MJ, Loebd V. A re-appraisal of the total biomass and annual production of Antarctic krill. Deep-Sea Res I Oceanogr Res Pap. 2009;56:727–40.

Santonja M, Minguez L, Gessner MO, Sperfeld E. Predator-prey interactions in a changing world: humic stress disrupts predator threat evasion in copepods. Oecologia. 2017;183:887–98.

Colbourne JK, Pfrender ME, Gilbert D, Thomas WK, Tucker A, Oakley TH, Tokishita S, Aerts A, Arnold GJ, Basu MK, et al. The ecoresponsive genome of Daphnia pulex. Science. 2011;331:555–61.

Castro H, Ramalheira F, Quintino V, Rodrigues AM. Amphipod acute and chronic sediment toxicity assessment in estuarine environmental monitoring: an example from Ria de Aveiro, NW Portugal. Mar Pollut Bull. 2006;53:91–9.

Kato Y, Kobayashi K, Oda S, Colbourn JK, Tatarazako N, Watanabe H, Iguchi T. Molecular cloning and sexually dimorphic expression of DM-domain genes in Daphnia magna. Genomics. 2008;91:94–101.

Toyota K, Kato Y, Sato M, Sugiura N, Miyagawa S, Miyakawa H, Watanabe H, Oda S, Ogino Y, Hiruta C, et al. Molecular cloning of doublesex genes of four Cladocera (water flea) species. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:239.

LeBlanc GA, Wang YH, Holmes CN, Kwon G, Medlock EK. A transgenerational endocrine signaling pathway in Crustacea. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61715.

Wu LT, Chu KH. Characterization of heat shock protein 90 in the shrimp Metapenaeus ensis: evidence for its role in the regulation of vitellogenin synthesis. Mol Reprod Dev. 2008;75:952–9.

Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–20.

Grabherr MG, Haas BJ, Yassour M, Levin JZ, Thompson DA, Amit I, Adiconis X, Fan L, Raychowdhury R, Zeng Q, et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:644–52.

Wood DE, Salzberg SL. Kraken: ultrafast metagenomic sequence classification using exact alignments. Genome Biol. 2014;15:R46.

Pertea G, Huang X, Liang F, Antonescu V, Sultana R, Karamycheva S, Lee Y, White J, Cheung F, Parvizi B, et al. TIGR gene indices clustering tools (TGICL): a software system for fast clustering of large EST datasets. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:651–2.

Haas BJ, Papanicolaou A, Yassour M, Grabherr M, Blood PD, Bowden J, Couger MB, Eccles D, Li B, Lieber M, et al. De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:1494–512.

Finn RD, Coggill P, Eberhardt RY, Eddy SR, Mistry J, Mitchell AL, Potter SC, Punta M, Qureshi M, Sangrador-Vegas A, et al. The Pfam protein families database: towards a more sustainable future. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D279–85.

Eddy SR. Accelerated profile HMM searches. PLoS Comput Biol. 2011;7:e1002195.

Mathelier A, Fornes O, Arenillas DJ, Chen CY, Denay G, Lee J, Shi W, Shyr C, Tan G, Worsley-Hunt R, et al. JASPAR 2016: a major expansion and update of the open-access database of transcription factor binding profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D110–5.

Hume MA, Barrera LA, Gisselbrecht SS, Bulyk ML. UniPROBE, update 2015: new tools and content for the online database of protein-binding microarray data on protein-DNA interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D117–22.

Xie Z, Hu S, Blackshaw S, Zhu H, Qian J. hPDI: a database of experimental human protein-DNA interactions. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:287–9.

Sievers F, Wilm A, Dineen D, Gibson TJ, Karplus K, Li W, Lopez R, McWilliam H, Remmert M, Soding J, et al. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal omega. Mol Syst Biol. 2011;7:539.

Price MN, Dehal PS, Arkin AP. FastTree 2--approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9490.

GC Y, Smith DK, Zhu HC, Guan Y, Lam TTY. GGTREE: an R package for visualization and annotation of phylogenetic trees with their covariates and other associated data. Methods Ecol Evol. 2017;8:28–36.

Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v3: an online tool for the display and annotation of phylogenetic and other trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:W242–5.

Gurkov A, Shchapova E, Bedulina D, Baduev B, Borvinskaya E, Meglinski I, Timofeyev M. Remote in vivo stress assessment of aquatic animals with microencapsulated biomarkers for environmental monitoring. Sci Rep. 2016;6:36427.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (project no. 41606143) and Direct Grant for Research from The Chinese University of Hong Kong (project no. 4053187) to JQ, a grant from Collaborative Research Fund of the Research Grants Council, Hong Kong SAR Government (project no. C4042-14G) to KHC, and grants from NSFC (project no. 11601343) and Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong (project no. 2016A030310038) to YH. JQ was partially supported by the Central Budget for the Appointment of Research Assistant Professor, The Chinese University of Hong Kong and a grant from the TUYF Foundation, Hong Kong. The funding agencies had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, or in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The database is freely available at http://qinlab.sls.cuhk.edu.hk/CrusTF. Sequences of crustacean genes other than TFs are also available on request by email (qinjing@cuhk.edu.hk or kahouchu@cuhk.edu.hk).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KHC and JQ designed the work and drafted the article. JQ also collected, processed the transcriptome data and performed bioinformatics analyses. YH and XJ contributed to the database and website construction. KYM and LY performed the evolutionary analysis. CHH worked for the in-house scripts for TF motif inference. LMT contributed to the data of 28 crab transcriptomes. RWTL identified crustacean TFs from GenBank data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

Not applicable

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1: Table S1.

List of crustacean transcriptome data. Table S2. Crustacean transcriptome data collection from Short Read Archive. Table S3. Crustacean transcriptome data collection from Transcriptome Shotgun Assembly. Table S4. Crustacean TFs from GenBank. Table S5. List of the 63 TF families identified in the crustacean species. (XLSX 336 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Qin, J., Hu, Y., Ma, K.Y. et al. CrusTF: a comprehensive resource of transcriptomes for evolutionary and functional studies of crustacean transcription factors. BMC Genomics 18, 908 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-017-4305-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-017-4305-2