Abstract

Background

Aspergillus westerdijkiae produces ochratoxin A (OTA) in Aspergillus section Circumdati. It is responsible for the contamination of agricultural crops, fruits, and food commodities, as its secondary metabolite OTA poses a potential threat to animals and humans. As a member of the filamentous fungi family, its capacity for enzymatic catalysis and secondary metabolite production is valuable in industrial production and medicine. To understand the genetic factors underlying its pathogenicity, enzymatic degradation, and secondary metabolism, we analysed the whole genome of A. westerdijkiae and compared it with eight other sequenced Aspergillus species.

Results

We sequenced the complete genome of A. westerdijkiae and assembled approximately 36 Mb of its genomic DNA, in which we identified 10,861 putative protein-coding genes. We constructed a phylogenetic tree of A. westerdijkiae and eight other sequenced Aspergillus species and found that the sister group of A. westerdijkiae was the A. oryzae - A. flavus clade. By searching the associated databases, we identified 716 cytochrome P450 enzymes, 633 carbohydrate-active enzymes, and 377 proteases. By combining comparative analysis with Kyoto Encyclopaedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), Conserved Domains Database (CDD), and Pfam annotations, we predicted 228 potential carbohydrate-active enzymes related to plant polysaccharide degradation (PPD). We found a large number of secondary biosynthetic gene clusters, which suggested that A. westerdijkiae had a remarkable capacity to produce secondary metabolites. Furthermore, we obtained two more reliable and integrated gene sequences containing the reported portions of OTA biosynthesis and identified their respective secondary metabolite clusters. We also systematically annotated these two hybrid t1pks-nrps gene clusters involved in OTA biosynthesis. These two clusters were separate in the genome, and one of them encoded a couple of GH3 and AA3 enzyme genes involved in sucrose and glucose metabolism.

Conclusions

The genomic information obtained in this study is valuable for understanding the life cycle and pathogenicity of A. westerdijkiae. We identified numerous enzyme genes that are potentially involved in host invasion and pathogenicity, and we provided a preliminary prediction for each putative secondary metabolite (SM) gene cluster. In particular, for the OTA-related SM gene clusters, we delivered their components with domain and pathway annotations. This study sets the stage for experimental verification of the biosynthetic and regulatory mechanisms of OTA and for the discovery of new secondary metabolites.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Aspergillus westerdijkiae (CBS 112803 = NRRL 3174), a filamentous fungus branched from the A. ochraceus taxon [1], has a worldwide distribution and mainly colonizes agricultural crops and various food commodities, such as coffee, beer, wine, milk, grapes, oranges, and juice [2–4]. Previous studies have shown that A. westerdijkiae is also present in house dust and indoor air fallout [5], and some other subtypes are found in deep sea environments [6, 7].

Filamentous fungi of the Aspergillus genus are among the most prolific sources of secondary metabolites with biomedical and commercial importance [6]. A. westerdijkiae is known as the main ochratoxin A (OTA)-producing species, of which approximately 70 % of the strains are able to produce OTA [8]. OTA, a polyketide secondary metabolite, is potentially carcinogenic in humans through its induction of oxidative DNA damage [9] and is neurotoxic, with a strong affinity for the brain [10]. In addition, OTA can induce renal adenomas and hepatocellular carcinomas in rodents [11]. Numerous studies aimed at the mechanism of OTA production and its activity have been conducted [12–16]. Researchers also developed a real-time quantitative PCR protocol to detect and quantify A. westerdijkiae contamination in grapes and green coffee beans, focussing on the ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 region within the rDNA unit, which serves as a tag to evaluate A. westerdijkiae contamination and has been frequently used to discriminate at the species level [17].

Thus far, phylogenetic studies examining A. westerdijkiae have had been performed with only three or four gene loci [1, 18]. A phylogenetic analysis using a small number of concatenated genes may have a high probability for supporting conflicting topologies, while an analysis with whole-genome data could provide greater resolving power by allowing trees to be constructed based on all available concatenated sets of genes [19]. In this study, we used 561 highly conserved single-copy orthologous gene sets found in whole genome-wide searches to infer the phylogenetic relationships between A. westerdijkiae and the eight other Aspergillus species.

Enzymatic degradation of plant polysaccharides in fungi is notable for its relevance in many industrial applications, such as paper, food, animal feed, biofuel, and chemicals [20–22]. Fungi have been used to subsist on various types of plant biomass as a carbon source by producing enzymes that degrade cell well polysaccharides in the exterior milieu into simple monomers for nutrition [21]. Localized degradation of the cell wall also allows for penetration and spreading across host tissues [23]. The CAZy database (http://www.cazy.org) has classified the enzymes degrading or modifying plant polysaccharides into carbohydrate-active enzymes and has divided them into different families. A previous study comparing eight sequenced Aspergilli genomes revealed that the related fungi employed diverse enzymatic strategies to degrade plant biomass and provided detailed categorization for these species. This study provided practical knowledge to further analyse the capability of plant polysaccharide depolymerization of A. westerdijkiae [22]. Interestingly, the latest studies revealed that A. westerdijkiae OTA production had no positive relationship with growth or sporulation and was markedly variable both qualitatively and quantitatively among different substrates [24, 25].

Fungi are also deemed to be a potential source of proteases due to their broad biochemical diversity [26]. Enzymatic proteolysis has many extremely important applications in the pharmaceutical, medical, food, and biotechnological industries [27]. The MEROPS database (http://merops.sanger.ac.uk) is an integrated resource for proteases and the proteins that inhibit proteases. This database has organized peptidases into various families on the basis of statistically significant similarities in amino acid sequences and includes a batch Blast prediction tool [28].

Until now, studies examining A. westerdijkiae have only employed low-throughput experimental approaches or in vitro observation to check for known characteristics and to explore unknown features. These methods are useful for making reliable conclusions but are not ideal for exploring unknown characteristics.

In this study, we sequenced and assembled a complete genome of A. westerdijkiae NRRL 3174 using an Illumina MiSeq platform. We analysed the genome to identify the genes that might be secreted and might contribute to pathogenicity and secondary metabolite biosynthesis. Domains of each component of all of the predicted SM gene clusters were annotated, and we provided the detailed annotation for two putative OTA-related gene clusters, a putative Notoamide biosynthetic gene cluster and a putative Hexadehydro-astechrome (HAS) biosynthetic gene cluster. We also examined the classification of the plant polysaccharide degradation enzymes and found that the union of GH3 and AA3 present in one of the OTA-related SM gene clusters might be associated with the responses of A. westerdijkiae growing in different media. We also compared its genome and proteome similarities, evolutionary relationship, and plant biomass degradation potential to those of eight sequenced Aspergillus species: A. flavus, A. clavatus, A. fumigatus, A. nidulans, A. niger, A. oryzae, A. terreus, and N. fischeri (Additional file 1: Table S1). The information contained in this study could be helpful for understanding the molecular mechanisms and the evolution of this important Aspergillus species.

Results and discussion

Genome details and comparative analysis

The A. westerdijkiae genome was sequenced to 142.0x coverage using an Illumina MiSeq platform [29]. The complete sequences for the Whole Genome Shotgun projects have been deposited at DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under the accession numbers LKBE00000000. The version described in this paper is the first version LKBE00000000.1. The genome assembly is approximately 36 M in size and includes 239 scaffolds with an N50 length of 1,603,627 bp (Table 1). Comparatively, A. westerdijkiae has a similar genome size to the sister group A. flavus and A. oryzae, which differ considerably from the others (Table 2). To assess the gene space in the A. westerdijkiae genome, we used a set of 248 core eukaryotic genes to perform CEGMA prediction, which showed that 234 out of 248 (94.35 %) genes were completely matched to our assembled genome. This finding suggested that we had successfully assembled approximately 95 % of all A. westerdijkiae genes [30]. In this case, 10,861 protein-coding genes were predicted using the annotation pipeline MAKER2 to integrate evidence from multiple databases with the gene-finding programs SNAP and AUGUSTUS. The predicted transcripts and proteins have been deposited in supplementary information (Additional file 2). These putative protein-coding genes cover 30.68 % of the nucleotide sequence of the A. westerdijkiae genome. Compared to increasing the genome size, using a strict prediction method may lead to a relatively lower value of gene density in A. westerdijkiae (Table 2). Of the 10,861 predicted genes of A. westerdijkiae, 3964 (36.5 %) were assigned as hypothetical, and 458 (4.2 %) were considered as unique, without any matches in the NCBI non-redundant (nr) database and the UniProt knowledgebase.

Over 200 scaffolds of A. westerdijkiae were finally assembled in this study. Any gaps between the scaffolds might be due to one of the reasons. Comparative analysis could be used to find conserved regions among the genomes and to infer the probable collinearity of the assembled scaffolds. Pairwise comparisons between A. westerdijkiae and the eight sequenced Aspergillus genomes were conducted by applying the scaffolds greater than 100 kb in these genomes to the NUCmer programs (Fig. 1) [31]. A total of 29 scaffolds from A. westerdijkiae larger than 100 kb in length and covering more than 97 % of the genome were extracted (Additional file 1: Table S2). Scaffolds 9, 17, and 75 displayed relative conservation among these sequenced Aspergilli, and scaffolds 5 and 23 were shown to be possibly syntenous.

Dotplot view of the Nucmer genome alignment between the A. westerdijkiae genome and the other selected Aspergillus genomes (A. oryzae, A. flavus, A. terreus, A. niger, A. fumigatus, N. fischeri, A. clavatus, A. nidulans). Each subgraph represents a comparison between the A. westerdijkiae genome and another selected Aspergillus genome. In each subgraph, the x-axis refers to the 29 largest supercontigs of A. westerdijkiae sorted in decreasing order of size, and the y-axis refers to the supercontigs of another selected genome sorted in decreasing order of size

Although in the same genus, the Aspergilli also show extensive structural reorganization and differ in their genome sequences. Only less than 0.2 % of the nucleotides of A. westerdijkiae were shared with Aspergilli, with an average of 88 % identity. And the alignment displayed an average of 68 % amino acid identity, comparable to similar findings among A. fumigatus, A. oryzae, and A. nidulans (Additional file 3: Table S3) [32]. A. westerdijkiae and A. nidulans showed the lowest similarity; therefore, we selected A. nidulans as the outgroup for the phylogenetic tree construction.

Phylogenetic relationship

In this study, we used the entire dataset of concatenated single-copy orthologous proteins to build the phylogenetic tree. Using the Perl script Proteinortho, 561 orthologous clusters were present as single copies across the nine Aspergillus species. We further built the maximum likelihood (ML) tree based on the orthologous proteins, selecting A. nidulans as the outgroup (Fig. 2) [33]. This tree illustrated that A. westerdijkiae was most closely related to A. oryzae and A. flavus and the opportunistic pathogen A. terreus. A. oryzae has been used in the fermentation process of several traditional Japanese beverages and sauces [34]. A. flavus is well known for producing the potent carcinogen aflatoxin [35]. The profile of this phylogenetic tree was consistent with those reported in previous studies [32, 36].

A maximum likelihood phylogenomic tree was inferred on the basis of 561 concatenated orthologous single-copy amino acid sequences of the nine Aspergillus genomes (A. oryzae, A. flavus, A. westerdijkiae, A. terreus, A. niger, A. fumigatus, N. fischeri, A. clavatus, A. nidulans) using the Dayhoff model in TREE-PUZZLE

Predicted secreted proteins involved in virulence or detoxification

A. westerdijkiae is one of the phytopathogenic fungi that can cause serious diseases. Secreted enzymes play crucial roles in pathogenicity and virulence [37]. With the in silico pipeline described in the Methods section, 801 out of the 10,861 (7.38 %) predicted proteins were potentially secreted proteins, close to the average 8 % found in other Aspergillus species [38]. By performing a whole-proteome Blast against the pathogen-host interaction (PHI) database, 3124 out of 10,861 (28.76 %) predicted proteins encoded by the A. westerdijkiae genome were determined to share homology with the genes implicated in pathogenicity and virulence in the PHI-Base, of which 219 (0.7 %) putative PHI-related proteins are potential secreted proteins. Cytochrome P450 enzymes not only participate in the production of the metabolites important for the organism’s internal needs but also play critical roles in adaptation to diverse environments by modifying harmful environmental chemicals. Using Blast to search the fungal Cytochrome P450 database, we found that 716 out of 10,861 (6.6 %) predicted proteins matched to 7711 out of 9209 (83.73 %) CYP450s, of which 52 putative CYP450 enzymes were predicted to be secreted, most of which were involved in pathogen-host interactions (Fig. 3, Additional file 4: Table S4). According to the result of orthologous analysis, 38 putative PHI-related genes can be found across all the sequenced Aspergilli, while 31 genes were only expressed in A. westerdijkiae.

Carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes)

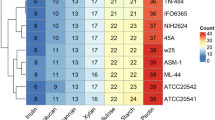

Secreted CAZymes are crucial for fungal biological activity. Using the common CAZy annotation pipeline (see Methods section) for genomic analysis of fungi, which was also adopted to perform similar analyses in previous studies [39, 40], we explored the A. westerdijkiae genome for genes coding carbohydrate-active enzymes and carbohydrate-binding modules (CBMs). We identified 633 putative CAZy-coding genes falling into 142 families and 53 putative CBM-coding genes in 20 families (Additional file 5: Table S5). The Wilcoxon rank-sum test based on the gene counts in these families showed that the family distribution of the enzyme genes had no significant difference (p > 0.1) between A. westerdijkiae and the other Aspergillus genomes. The heatmap based on family classification suggested that A. westerdijkiae, along with A. oryzae and A. flavus, tend to be similar in degrading carbohydrates (Fig. 4). A. niger, A. westerdijkiae, A. oryzae, and A. flavus are known to colonize cereal grains, legumes, tree nuts, fruits, and vegetables, while the species in another clade, including A. clavatus, A. fumigatus, N. fischeri, A. nidulans, and A. terreus, are involved in decomposing vegetation and decaying organic matter, such as animal manure.

Comparison of the CAZymes identified in the genomes of the selected fungi using hierarchical clustering. The fungi analysed along with A. westerdijkiae were A. oryzae, A. flavus, A. terreus, A. niger, A. fumigatus, N. fischeri, A. clavatus, and A. nidulans. The enzyme families are represented by their classes (GH: glycoside hydrolases, GT: glycosyltransferases, PL: polysaccharide lyases, CE: carbohydrate esterases, and CBM: chitin binding modules) and the family numbers from the HMM predictions based on the carbohydrate-active enzyme database. The abundance levels of the different enzymes within a family are represented by a colour scale from the lowest (dark blue) to the highest occurrences (dark red) per species

The glycoside hydrolase (GH), carbohydrate esterase (CE), and polysaccharide lyase (PL) groups include major plant polysaccharide degradation (PDD) enzyme families, also called cell wall-degrading enzymes (CWDE) due to their role in the disintegration of the plant cell wall exerted by bacterial and fungal pathogens [41]. The proteins containing CAZy domains in these families were considered as candidate proteins involved in the enzymatic degradation of plant polysaccharides (Additional file 5: Table S6). In the A. westerdijkiae genome, the percentages of PDD-related proteins in GH and PL groups were 60.5 and 91.7 %, respectively, which ranked together second only to A. terreus (60.7 and 93.3 %). We found that 23.4 % of the 633 putative CAZy-coding genes were PPD-related in the CE group, which had a low distribution in the Aspergillus genomes, which was comparable to the percentages found in other species [42].

Using comprehensive annotation and comparison analysis, we predicted 228 PDD-related enzymes, of which 187 (82 %) enzymes were annotated based on orthologous clustering. This annotation covered 180 PPD-related candidate proteins with CAZy domains (Additional file 4: Table S7). Of the remaining candidate proteins, 18 genes were inferred in terms of Kyoto Encyclopaedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), Conserved Domains Database (CDD), and Pfam annotations, whereas the 23 remaining potential PDD-related enzyme genes with only CAZy annotations were unknown due to the lack of reliable information, requiring further experimental data to infer their functions (Additional file 5: Table S8). With this information regarding the putative enzyme code, we compared the degradation potentials for cellulose, xyloglucan, xylan, galactomannan, pectin, starch, and insulin with those of the eight Aspergilli based on their genome content (Additional file 5: Table S9)[42]. We found that the predicted proteins of the A. westerdijkiae genome covered all of the enzyme activities, with many of them involved in pectin degradation.

In addition, the glycoside hydrolase family 18 (GH18), which contains all fungal chitinases, was responsible for the remodelling and recycling of the fungus’ own cell wall with other cell wall degrading enzymes [43]. GH18 was the third major family in the glycoside hydrolase class. Of 18 predicted enzymes in GH18, five were identified as secreted and pathogenic. The Auxiliary Activities (AAs) class contained enzymes with the potential capacity to help the original GH, PL, and CE enzymes gain access to the carbohydrates encrusted in the plant cell wall. In this class, the AA7 family contained 24 secreted enzymes. We also identified 12 secreted enzymes belonging to the family LPMO (AA9); these enzymes are crucial for lignin breakdown [44]. AAs contained the highest proportion (88.24 %) of the enzymes related to pathogenicity and virulence. CBM50 carbohydrate-binding modules, also known as LysM domains, were widely conserved in the fungal kingdom and might be functional in the virulence effects of plant pathogenic fungi for dampening host defence [45, 46]. Based on the CAZy annotation pipeline, we identified 10 predicted proteins containing CBM50 modules. In summary, 137 out of 274 putative secreted CAZymes were predicted to be potential PHI-related proteins. Most of these PHI-related CAZymes were in the family AA7 (23), GH3 (17), CE10 (16), AA3 (11), and GH28 (11) (Additional file 4: Table S4). These families may be observed in the close phylogenetic profiling clusters in Fig. 4.

Proteases

Peptidases, which degrade proteins to provide an alternative carbon source, can be secreted during the infection process [47, 48]. Therefore, we performed a batch Blast search against the MEROPS protease database and identified 377 protease-coding genes, which were classified into 6 categories consisting of 91 subfamilies, and 7 inhibitor-coding genes (Additional file 6: Table S10). Of all of these putative proteases, 69 were predicted as secreted proteases, of which 39 exhibited homology with the pathogenicity- and virulence-related genes in the PHI database (Fig. 3) and belonged primarily to the families S09X (17), S10 (8), and A01A (8). All of the predicted proteases in the S09X family contained CE10 domains (Additional file 4: Table S4).

From a general view, the largest category of predicted proteases in the A. westerdijkiae genome was serine peptidases, with 176 genes belonging to 13 families. The top two families of predicted serine peptidases were prolyl oligopeptidase (79 genes) and prolyl aminopeptidase (58 genes). S9 was the largest family identified in the genome. Metallo (M) (103 genes) was the second largest protease category, of which glutamate carboxypeptidase (16 genes) was the largest family. Other abundant families were pepsin A (11 genes) within Aspartic (A) proteases, ubiquitin-specific peptidase 14 (17 genes) in Cysteine (C) proteases, and Archaean-proteasome beta component (14 genes) in Threonine (T) proteases.

The biosynthetic potential of A. westerdijkiae suggested by a large number of secondary biosynthetic gene clusters

Filamentous fungi produce many bioactive secondary metabolites, such as various mycotoxins or other bioactive compounds that have been exploited in pharmaceuticals [49, 50]. The genes responsible for the production of the secondary metabolites tend to be organized in biosynthetic gene clusters [38]. Using the scaffolds as the query sequences of the antiSMASH 3.0 platform, we found many short and dense fragments present in some SM gene clusters, suggesting low prediction accuracy. Therefore, we constructed putative SM gene clusters according to the procedure described in the Methods section. In this case, a total of 88 putative secondary biosynthetic gene clusters, which spread on 21 scaffolds and a contig, were identified (Additional file 7: Table S11). The total length of these scaffolds and contig covered 89.96 % of the assembled sequences. Many of the putative SM gene clusters belong to type I pks (t1pks) or non-ribosomal peptide synthase (nrps) gene clusters, while the remainder were terpene, indole, or other hybrid gene clusters (Table 3). The number of putative pks gene, nrps gene and hybrid nrps/pks gene of A. westerdijkiae is comparable to other Aspergilli predicted by previous studies, such as A. nomius, A. nidulans, A. flavus and A. oryzae [51–53].

The previous studies successively concluded two portions of the sequences of the t1pks genes involved in the biosynthesis of the OTA mycotoxin [15, 16]. Silencing either of the two genes might inhibit OTA production, suggesting that the two clusters jointly play a role [2]. In this study, we predicted more complete sequences of the two t1pks genes and classified them into two distinct putative SM gene clusters: i) Cluster37, located on scaffold14 (locus: 390369–4449037), includes 15 genes; and ii) Cluster69, located on scaffold45 (locus: 255712–339653), includes 17 genes(Fig. 5, Additional file 7). The genes in cluster37 successively encoded a pks (awe04182), an nrps (awe04183), a cytochrome P450 monooxygenase (awe04184), a bZIP transcription regulator (awe04185), and a halogenase (awe04186) (Fig. 5a, Additional file 8: Table S12). They shared 66.67, 56.62, 67.32, 42.86, and 77.14 % amino acid identity with 5 out of 6 co-expressed genes (CEGs) (173482, 132610, 517149, 7821 and 209543) in cluster38 of Aspergillus carbonarius, respectively [54]. However, the rest of the genes in both clusters were non-homologous under the Blast search E-value threshold of 1e-10. In addition, cluster37 of A. westerdijkiae also included a Zn2Cys transcription regulator (awe04179) and a sugar transporter (awe04190).

The putative cluster69 encoded a pks (sc45_org87), a cytochrome P450 monooxygenase (awe08996), an Acyl-CoA synthetase (awe08993), and two transporters (awe08996, awe08997) (Fig. 5b, Additional file 8: Table S13). The pks gene was originally classified as two separate genes (awe08994, awe08995) by the MAKE2 prediction pipeline. Further domain prediction and homology analysis suggested the two genes should be integrated despite the junction showing low similarity in Blast search. Therefore, we chose the gene model sc45_org87 predicted by antiSMASH as the integrated gene in this cluster, which shares 32.42 % amino acid identity with the CEG 511653 in cluster4 of Aspergillus carbonarius, while awe08996 shares 31.22 % amino acid identity with the adjacent CEG 392816 coding a cytochrome P450 monooxygenase. No additional homologous genes were found between these two clusters. A putative acetyl-CoA synthetase was predicted to be present next to the pks. Acetyl-CoA, used as a carbon source in polyketide biosynthesis, is likely to be a precursor for OTA synthesis [15, 55]. We subsequently identified a GH3 enzyme gene, acting as a beta glucosidase, in the 3’ direction of the pks gene. Pathway analysis indicated that this putative GH3 enzyme gene participated in starch and sucrose metabolism. Based on the Blast and domain analyses, we also predicted an AA3 enzyme gene close to the GH3 enzyme genes. The predicted AA3 enzyme gene belonged to the glucose-methanol-choline (GMC) oxidoreductase family and could be further categorized into the AA3_2 family containing glucose 1-oxidase. We found that the GH3 and AA3 enzymes could be classified into the close phylogenetic profiling clusters summarized in the heatmap of CAZymes, which suggested that the AA3 enzymes might act in conjunction with GH3 enzymes. Moreover, it was observed that these two genes did not belong to any orthologous cluster. In summary, these two genes might have important influences on OTA production in various substrates. This suggestion is in agreement with the observation that A. westerdijkiae possessed the highest capability for producing OTA in media containing high amounts of sucrose and glucose, such as paprika-based medium, while OTA was absent in grape-based medium, in which fructose is the most abundant compound [24]. With domain prediction, the structure of pks in putative cluster37 of A. westerdijkiae, the partial sequence of which was reported as LC35-12 [GenBank: AAT92023.1), was KS-AT-DH-MT-ER-KR-ACP [16, 56]. The structure of pks in putative cluster69 of A. westerdijkiae, which shows high identity (649/670) with the validated OTA-related portion of “aoks1” [GenBank: AAT92024.1], was KS-AT-DH-MT-KR-ACP-C-A. These two putative structures of pks could be divided into two different fungus-reducing PKS clades: the former was clade I, while the latter was clade II due to the loss of the ER domain [57]. We also detected a putative methylsalicylic acid pks gene (awe07918) with 96.22 % sequence identity with “aomsas” [GenBank: AAS98200.1], pks gene involved in the biosynthesis of isoasperlactone and asperlactone and reported previously in A. westerdijkiae [58].

Non-ribosomal peptide synthase genes are responsible for the synthesis of natural peptide-based microbial products. We identified a total of 17 putative nrps genes distributed in different gene clusters in the A. westerdijkiae genome. We further predicted a notoamide biosynthetic gene cluster centred on an nrps gene in the A. westerdijkiae genome, suggesting that A. westerdijkiae should be able to produce notoamide and the related structural derivatives (Fig. 6) [59, 60]. Moreover, because of the homology shared with the characterized biosynthetic gene clusters in A. fumigatus Af239, A. westerdijkiae is likely to produce the widely occurring siderophore hexadehydro-astechrome (HAS) (Fig. 7) [61–64]. In the A. westerdijkiae genome, we also predicted several nrps gene clusters producing di- and three-peptide alkaloids containing the amino acid anthranilate.

The putative notoamide biosynthetic gene cluster of A. westerdijkiae found in this study and the comparison of this cluster with the notoamide cluster reported for Aspergillus versicolor and Aspergillus sp. MF297-2. Gene cluster description of Aspergillus versicolor and Aspergillus sp. MF297-2 was acquired from Minimum Information about a Biosynthetic Gene cluster (MIBiG) database under accession number BGC0000818 (GenBank: JQ708194, positions: 1–43815) and BGC0001084 (GenBank: HM622670, positions: 1–42456), respectively

The putative hexadehydro-astechrome (HAS) biosynthetic gene cluster of A. westergijkiae found in this study and the comparison of this cluster with the hexadehydro-astechrome cluster reported for Aspergillus fumigatus Af239. Gene cluster description of A. fumigatus was acquired from MIBiG database under accession number BGC0000372 (GenBank CM000171, positions 3423866–3446129)

In A. westerdijkiae, we also predicted several hybrid nrps/pks gene whose products remain to be determined. In addition to the pks, nrps, and hybrid nrps/pks gene clusters, we also identified 10 gene clusters likely to produce terpenes, including two hybrid terpene-pks gene clusters. In this study, we were able to observe almost all of the secondary metabolism clusters containing the reported genes or gene portions.

Conclusions

This genome-wide comparative study facilitated our understanding of the evolutionary relationships between A. westerdijkiae and other sequenced Aspergillus species. The analysis of genome characteristics and evolutionary relationships provided evidence suggesting that the A. westerdijkiae genome was most closely related to the A. oryzae genome. A. westerdijkiae was capable of producing abundant plant polysaccharide-degrading enzymes and secreted proteases, and the results related to these findings in our study might serve as a basis for understanding the principles of A. westerdijkiae colonization and pathogenicity. With respect to the secondary metabolites, we identified numerous secondary biosynthetic gene clusters, including OTA gene clusters and a few other clusters with predicted products. Some of these gene clusters did not share similarity with any characterized biosynthetic gene clusters, indicating that A. westerdijkiae could potentially produce novel secondary metabolites. These findings set the stage for later experimental studies and might be helpful for further understanding the pathogenicity of A. westerdijkiae.

Methods

Culturing and extraction of genomic DNA

Aspergillus westerdijkiae CBS112803 strain was obtained from Centraalbureau Voor Schimmelculture, Netherlands (CBS) and was cultured in 50-ml flasks containing LMM broth for 6 days at 25 °C with shaking at 120 rpm. The fungal mycelial mat was harvested and ground into a fine powder with liquid nitrogen in a mortar. The concentration of the DNA sample was measured using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer, and the sample was resolved on an agarose gel before it was sent to Macrogen Inc., Korea for whole-genome sequencing.

Genome sequencing and assembly

For the whole-genome shotgun sequencing of A. westerdijkiae, the Illumina MiSeq platform was adopted with two meta-pair libraries, one 3 kb and the other 10 kb [29]. The raw sequence data coming from the high-throughput sequencing pipelines were applied to the program FastQC (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc) for quality control of sequencing. The reads were filtered before assembly such that for a pair of paired-end (PE) reads, each read should have more than 90 % of bases with a base quality greater than or equal to Q20. The contigs and scaffolds were assembled using the short-read assembly tool SOAPdenovo2 [65]. CEGMA, a bioinformatics tool for assessing the completeness of the gene space, was employed with a refined set of 248 core eukaryotic genes to evaluate the assembly efficiency of the sequenced genome [30]. To identify genome repetitive sequences, assembled scaffolds were supplied to RepeatMasker (RMLib: 20140131 & Dfam: 1.3 as fungi repetitive sequence library) [66].

Genome annotation and classification

After masking the identified repetitive sequences, gene prediction in A. westerdijkiae was implemented according to the MAKER2 pipeline [67, 68]. An initial run of MAKER v2.31.8 was performed to construct the phylogenetic tree using ab initio gene-predictor SNAP v2013-11-29 [69]. To train the SNAP, CEGMA, a bioinformatics tool for building a highly reliable set of gene annotations in the absence of experimental data, was adopted [70]. All expressed sequence tags (ESTs) and protein sequences in the Refseq (75,695), UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot (3617), and GenBank (148,141) databases via the NCBI Taxonomy (by February 2015) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/taxonomy) were pooled as alternative EST and protein homology evidence. A subsequent run of MAKER was performed to increase the sensitivity of gene identification. AUGUSTUS v2.55 [71] was added into the initial MAKER pipeline. According to the evolutionary relationships described above, we selected “Aspergillus oryzae” as the default training set of AUGUSTUS. The final outcome was reached by combining the predictions of SNAP and AUGUSTUS. The putative proteins were aligned against the NCBI nr, UniProtKB (Swiss-Prot and TrEMBL), and KEGG databases using BLASTP with the cutoff E-value set at 1e-10. The predicted genes were then aligned against the CDD database using rpsBLAST. The domain compositions were analysed by performing a HMMER v3.1b1 (http://hmmer.org/) scan based on the profiles compiled from Pfam (by February 2015).

All proteomes were scanned to predict subcellular localization using TargetP v1.1b [72]. The remaining proteins were investigated using the Hidden Markov Model (HMM) in SignalP v4.1 to look for signal peptides [73]. These proteins were then scanned for the presence of transmembrane domains using TMHMM v2.0c [74]. To reduce redundancy, the secreted proteins were clustered using CD-HIT (v4.5.4, with default parameters) if they shared more than 90 % identity over a range of above 50 % of the sequence length [75]. A single representative sequence was selected from each protein cluster. To evaluate the potential of a gene to produce secondary metabolites, both the assembled scaffolds and the 10,861 predicted proteins of the A. westerdijkiae genome were supplied to antiSMASH (v3.0.5, with default parameters, except for checking the “DNA of Eukaryotic Origin” box) [76]. To conclude the structure of each predicted SM cluster, the following rules were adopted: firstly, the boundaries were determined in accordance with the outputs from antiSMASH, with the scaffolds as the query submission; secondly, the predicted proteins, which were located in the intervals or overlapped with each side of the boundaries, were selected to construct the final clusters; lastly, the SM gene clusters of interest were further examined according to the domain annotations. To identify genes involved in pathogenicity and virulence in the A. westerdijkiae genome, Blastp with a cut-off E-value set at 1e-10 was adopted to search against the Pathogen Host Interactions (PHI) database (by April 2015), which contains experimentally validated pathogenicity, virulence, and effector genes of fungal, oomycete, and bacterial pathogens [77]. The genome-encoding cytochrome P450s were annotated using Blastp to search the fungal Cytochrome P450 database (by April 2015) with a cut-off E-value set at 1e-10 [78, 79]. Proteomes were classified into proteolytic enzyme families by performing a batch Blast search against the MEROPS protease database (release 9.13) [80, 81], and carbohydrate-active enzymes were classified using a HMMER (v3.1b1, with default parameters) scan against the profiles compiled with dbCAN release 4.0 [82] based on the CAZy database [83]. Based on orthologue analysis and functional annotation, PDD enzyme-related genes were screened and classified into different enzyme coding categories [22, 42]. Statistical comparisons of carbohydrate active enzymes and peptidases between A. westerdijkiae and the eight other Aspergillus species were made using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test in the R platform.

Genome comparative analyses

Pair-wise sequence alignments between A. westerdijkiae and the eight other sequenced Aspergillus species, of which four genome sequences have been published (A. fumigatus [84], A. nidulans [32], A. niger [85], A. oryzae [34]) and four others assembled and annotated (A. flavus [86], A. clavatus [36], A. terreus [36], Neosartorya fischeri [36]), were performed using the Nucmer and Promer programs in the MUMmer v3.23 package (http://mummer.sourceforge.net/) [31]. The corresponding chromosome information was acquired from the Aspergillus genome database (AspGD) (May 2015) (http://www.aspergillusgenome.org/). Protein sequences of the other eight species presented in the comparative analysis were all acquired from the Aspergillus Comparative Database (May 2015) (http://www.broadinstitute.org/). From the eight Aspergillus species, supercontigs larger than 100 kb were aligned against the 29 largest A. westerdijkiae supercontigs.

The phylogenetic tree of A. westerdijkiae and the other eight Aspergillus species was constructed using whole genome-wide sequences. Orthologous protein prediction was performed using Proteinortho (v5.11, with default parameters, except that identity = 75) [87]. Among the predicted orthologous gene clusters, 561 highly conserved single-copy gene clusters were chosen and aligned using MUSCLE (v3.8.31_i86linux64, with default parameters) [88]. To remove divergence and ambiguously aligned blocks from the alignment, Gblocks (v0.91b) [89] was employed under the default parameter setting. Trimmed alignments of orthologous sequences were concatenated using a Perl script FASconCAT (v1.02, with default parameters) [90], and a maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree was created using the Dayhoff model in TREE-PUZZLE v5.3.rc16 [91] with 1000 bootstrap replicates. The tree was visualized using Figtree v1.42 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree).

Abbreviations

antiSMASH, Antibiotics & Secondary Metabolite Analysis Shell; AspGD, Aspergillus genome database; BLAST, Basic local alignment search tool; CAZyme, Carbohydrate activity enzyme; CBM, Carbohydrate binding module; CDD, Conserved Domains Database; CE, Carbohydrate esterase; CEG, Co-expressed gene; CWDE, Cell wall degrading enzyme; CYP450, Cytochrome P450; GH, Glycoside hydrolases; GT, Glycosyl transferase; HAS, Hexadehydro-astechrome; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopaedia of Genes and Genomes; ML, Maximum likelihood; nr, NCBI non-redundant; NRPS, Non-ribosomal peptide synthase; OTA, Ochratoxin A; PHI, Pathogen-host interaction; PKS, Polyketide synthase; PL, Polysaccharide lyase; PPD, Plant polysaccharide degradation; SM, Secondary metabolite; T1PKS, Type I PKS

References

Visagie CM, Varga J, Houbraken J, Meijer M, Kocsube S, Yilmaz N, Fotedar R, Seifert KA, Frisvad JC, Samson RA. Ochratoxin production and taxonomy of the yellow aspergilli (Aspergillus section Circumdati). Stud Mycol. 2014;78:1–61.

Morello LG, Sartori D, de Oliveira Martinez AL, Vieira ML, Taniwaki MH, Fungaro MH. Detection and quantification of Aspergillus westerdijkiae in coffee beans based on selective amplification of beta-tubulin gene by using real-time PCR. Int J Food Microbiol. 2007;119(3):270–6.

Diaz GA, Torres R, Vega M, Latorre BA. Ochratoxigenic Aspergillus species on grapes from Chilean vineyards and Aspergillus threshold levels on grapes. Int J Food Microbiol. 2009;133(1–2):195–9.

Marino A, Nostro A, Fiorentino C. Ochratoxin A production by Aspergillus westerdijkiae in orange fruit and juice. Int J Food Microbiol. 2009;132(2–3):185–9.

Mikkola R, Andersson MA, Hautaniemi M, Salkinoja-Salonen MS. Toxic indole alkaloids avrainvillamide and stephacidin B produced by a biocide tolerant indoor mold Aspergillus westerdijkiae. Toxicon. 2015;99:58–67.

Fredimoses M, Zhou X, Ai W, Tian X, Yang B, Lin X, Xian JY, Liu Y. Westerdijkin A, a new hydroxyphenylacetic acid derivative from deep sea fungus Aspergillus westerdijkiae SCSIO 05233. Nat Prod Res. 2015;29(2):158–62.

Peng J, Zhang XY, Tu ZC, Xu XY, Qi SH. Alkaloids from the deep-sea-derived fungus Aspergillus westerdijkiae DFFSCS013. J Nat Prod. 2013;76(5):983–7.

Sartori D, Massi FP, Ferranti LS, Fungaro MH. Identification of Genes Differentially Expressed Between Ochratoxin-Producing and Non-Producing Strains of Aspergillus westerdijkiae. Indian J Microbiol. 2014;54(1):41–5.

Palma N, Cinelli S, Sapora O, Wilson SH, Dogliotti E. Ochratoxin A-induced mutagenesis in mammalian cells is consistent with the production of oxidative stress. Chem Res Toxicol. 2007;20(7):1031–7.

Belmadani A, Steyn PS, Tramu G, Betbeder AM, Baudrimont I, Creppy EE. Selective toxicity of ochratoxin A in primary cultures from different brain regions. Arch Toxicol. 1999;73(2):108–14.

Pfohl-Leszkowicz A. Ochratoxin A, ubiquitous mycotoxin contaminating human food. Comptes rendus des seances de la Societe de biologie et de ses filiales. 1994;188(4):335–53.

Gil-Serna J, Patino B, Cortes L, Gonzalez-Jaen MT, Vazquez C. Mechanisms involved in reduction of ochratoxin A produced by Aspergillus westerdijkiae using Debaryomyces hansenii CYC 1244. Int J Food Microbiol. 2011;151(1):113–8.

Abarca ML, Bragulat MR, Cabanes FJ. A new in vitro method to detect growth and ochratoxin A-producing ability of multiple fungal species commonly found in food commodities. Food Microbiol. 2014;44:243–8.

Huffman J, Gerber R, Du L. Recent advancements in the biosynthetic mechanisms for polyketide-derived mycotoxins. Biopolymers. 2010;93(9):764–76.

Bacha N, Atoui A, Mathieu F, Liboz T, Lebrihi A. Aspergillus westerdijkiae polyketide synthase gene “aoks1” is involved in the biosynthesis of ochratoxin A. Fungal Genet Biol. 2009;46(1):77–84.

O’Callaghan J, Caddick MX, Dobson AD. A polyketide synthase gene required for ochratoxin A biosynthesis in Aspergillus ochraceus. Microbiology. 2003;149(Pt 12):3485–91.

Gil-Serna J, Gonzalez-Salgado A, Gonzalez-Jaen MA, Vazquez C, Patino B. ITS-based detection and quantification of Aspergillus ochraceus and Aspergillus westerdijkiae in grapes and green coffee beans by real-time quantitative PCR. Int J Food Microbiol. 2009;131(2–3):162–7.

Peterson SW. Phylogenetic analysis of Aspergillus species using DNA sequences from four loci. Mycologia. 2008;100(2):205–26.

Rokas A, Williams BL, King N, Carroll SB. Genome-scale approaches to resolving incongruence in molecular phylogenies. Nature. 2003;425(6960):798–804.

van den Brink J, de Vries RP. Fungal enzyme sets for plant polysaccharide degradation. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;91(6):1477–92.

Rytioja J, Hilden K, Yuzon J, Hatakka A, de Vries RP, Makela MR. Plant-polysaccharide-degrading enzymes from Basidiomycetes. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2014;78(4):614–49.

Benoit I, Culleton H, Zhou M, DiFalco M, Aguilar-Osorio G, Battaglia E, Bouzid O, Brouwer CP, El-Bushari HB, Coutinho PM, et al. Closely related fungi employ diverse enzymatic strategies to degrade plant biomass. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2015;8:107.

Zhao Z, Liu H, Wang C, Xu JR. Comparative analysis of fungal genomes reveals different plant cell wall degrading capacity in fungi. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:274.

Gil-Serna J, Patino B, Cortes L, Gonzalez-Jaen MT, Vazquez C. Aspergillus steynii and Aspergillus westerdijkiae as potential risk of OTA contamination in food products in warm climates. Food Microbiol. 2015;46:168–75.

Lai M, Semeniuk G, Hesseltine CW. Conditions for production of ochratoxin A by Aspergillus species in a synthetic medium. Appl Microbiol. 1970;19(3):542–4.

de Castro RJS, Sato HH. Protease from Aspergillus oryzae: Biochemical Characterization and Application as a Potential Biocatalyst for Production of Protein Hydrolysates with Antioxidant Activities. J Food Processing. 2014;2014:11.

Ramakrishna V, Rajasekhar S, Reddy LS. Identification and purification of metalloprotease from dry grass pea (Lathyrus sativus L.) seeds. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2010;160(1):63–71.

Rawlings ND, Barrett AJ, Finn R. Twenty years of the MEROPS database of proteolytic enzymes, their substrates and inhibitors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(D1):D343–50.

Caporaso JG, Lauber CL, Walters WA, Berg-Lyons D, Huntley J, Fierer N, Owens SM, Betley J, Fraser L, Bauer M, et al. Ultra-high-throughput microbial community analysis on the Illumina HiSeq and MiSeq platforms. ISME J. 2012;6(8):1621–4.

Parra G, Bradnam K, Ning Z, Keane T, Korf I. Assessing the gene space in draft genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(1):289–97.

Kurtz S, Phillippy A, Delcher AL, Smoot M, Shumway M, Antonescu C, Salzberg SL. Versatile and open software for comparing large genomes. Genome Biol. 2004;5(2):R12.

Galagan JE, Calvo SE, Cuomo C, Ma LJ, Wortman JR, Batzoglou S, Lee SI, Basturkmen M, Spevak CC, Clutterbuck J, et al. Sequencing of Aspergillus nidulans and comparative analysis with A. fumigatus and A. oryzae. Nature. 2005;438(7071):1105–15.

Pontecorvo G, Roper JA, Hemmons LM, Macdonald KD, Bufton AW. The genetics of Aspergillus nidulans. Adv Genet. 1953;5:141–238.

Machida M, Asai K, Sano M, Tanaka T, Kumagai T, Terai G, Kusumoto K, Arima T, Akita O, Kashiwagi Y, et al. Genome sequencing and analysis of Aspergillus oryzae. Nature. 2005;438(7071):1157–61.

Martins ML, Martins HM, Bernardo F. Aflatoxins in spices marketed in Portugal. Food Addit Contam. 2001;18(4):315–9.

Wortman JR, Fedorova N, Crabtree J, Joardar V, Maiti R, Haas BJ, Amedeo P, Lee E, Angiuoli SV, Jiang B, et al. Whole genome comparison of the A. fumigatus family. Med Mycol. 2006;44(s1):3–7.

Gonzalez-Fernandez R, Jorrin-Novo JV. Contribution of proteomics to the study of plant pathogenic fungi. J Proteome Res. 2012;11(1):3–16.

Marcet-Houben M, Ballester AR, de la Fuente B, Harries E, Marcos JF, Gonzalez-Candelas L, Gabaldon T. Genome sequence of the necrotrophic fungus Penicillium digitatum, the main postharvest pathogen of citrus. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:646.

Larriba E, Jaime MD, Carbonell-Caballero J, Conesa A, Dopazo J, Nislow C, Martin-Nieto J, Lopez-Llorca LV. Sequencing and functional analysis of the genome of a nematode egg-parasitic fungus, Pochonia chlamydosporia. Fungal Genet Biol. 2014;65:69–80.

Gao Q, Jin K, Ying SH, Zhang Y, Xiao G, Shang Y, Duan Z, Hu X, Xie XQ, Zhou G, et al. Genome sequencing and comparative transcriptomics of the model entomopathogenic fungi Metarhizium anisopliae and M. acridum. PLoS Genet. 2011;7(1):e1001264.

Ospina-Giraldo MD, Griffith JG, Laird EW, Mingora C. The CAZyome of Phytophthora spp.: a comprehensive analysis of the gene complement coding for carbohydrate-active enzymes in species of the genus Phytophthora. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:525.

Couturier M, Navarro D, Olive C, Chevret D, Haon M, Favel A, Lesage-Meessen L, Henrissat B, Coutinho PM, Berrin JG. Post-genomic analyses of fungal lignocellulosic biomass degradation reveal the unexpected potential of the plant pathogen Ustilago maydis. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:57.

Gruber S, Seidl-Seiboth V. Self versus non-self: fungal cell wall degradation in Trichoderma. Microbiology. 2012;158(Pt 1):26–34.

Levasseur A, Drula E, Lombard V, Coutinho PM, Henrissat B. Expansion of the enzymatic repertoire of the CAZy database to integrate auxiliary redox enzymes. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2013;6(1):41.

de Jonge R, Thomma BP. Fungal LysM effectors: extinguishers of host immunity? Trends Microbiol. 2009;17(4):151–7.

de Jonge R, van Esse HP, Kombrink A, Shinya T, Desaki Y, Bours R, van der Krol S, Shibuya N, Joosten MH, Thomma BP. Conserved fungal LysM effector Ecp6 prevents chitin-triggered immunity in plants. Science (New York, NY). 2010;329(5994):953–5.

Monod M, Capoccia S, Lechenne B, Zaugg C, Holdom M, Jousson O. Secreted proteases from pathogenic fungi. Int J Med Microbiol. 2002;292(5–6):405–19.

Desjardins CA, Champion MD, Holder JW, Muszewska A, Goldberg J, Bailao AM, Brigido MM, Ferreira ME, Garcia AM, Grynberg M, et al. Comparative genomic analysis of human fungal pathogens causing paracoccidioidomycosis. PLoS Genet. 2011;7(10):e1002345.

Medema MH, Blin K, Cimermancic P, de Jager V, Zakrzewski P, Fischbach MA, Weber T, Takano E, Breitling R. antiSMASH: rapid identification, annotation and analysis of secondary metabolite biosynthesis gene clusters in bacterial and fungal genome sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(Web Server issue):W339–46.

Khaldi N, Seifuddin FT, Turner G, Haft D, Nierman WC, Wolfe KH, Fedorova ND. SMURF: Genomic mapping of fungal secondary metabolite clusters. Fungal Genet Biol. 2010;47(9):736–41.

Inglis DO, Binkley J, Skrzypek MS, Arnaud MB, Cerqueira GC, Shah P, Wymore F, Wortman JR, Sherlock G. Comprehensive annotation of secondary metabolite biosynthetic genes and gene clusters of Aspergillus nidulans, A. fumigatus, A. niger and A. oryzae. BMC Microbiol. 2013;13:91–1.

Keller NP, Turner G, Bennett JW. Fungal secondary metabolism - from biochemistry to genomics. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3(12):937–47.

Moore GG, Mack BM, Beltz SB. Genomic sequence of the aflatoxigenic filamentous fungus Aspergillus nomius. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:551.

Gerin D, De Miccolis Angelini RM, Pollastro S, Faretra F. RNA-Seq Reveals OTA-Related Gene Transcriptional Changes in Aspergillus carbonarius. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0147089.

Buchanan RL, Bennett J. Nitrogen regulation of polyketide mycotoxin production. Boca Raton, Fla: Nitrogen source control of microbial processes CRC Press; 1988. p. 137–49.

Dao HP, Mathieu F, Lebrihi A. Two primer pairs to detect OTA producers by PCR method. Int J Food Microbiol. 2005;104(1):61–7.

Kroken S, Glass NL, Taylor JW, Yoder OC, Turgeon BG. Phylogenomic analysis of type I polyketide synthase genes in pathogenic and saprobic ascomycetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(26):15670–5.

Bacha N, Dao HP, Atoui A, Mathieu F, O’Callaghan J, Puel O, Liboz T, Dobson AD, Lebrihi A. Cloning and characterization of novel methylsalicylic acid synthase gene involved in the biosynthesis of isoasperlactone and asperlactone in Aspergillus westerdijkiae. Fungal Genet Biol. 2009;46(10):742–9.

Ding Y, de Wet JR, Cavalcoli J, Li S, Greshock TJ, Miller KA, Finefield JM, Sunderhaus JD, McAfoos TJ, Tsukamoto S, et al. Genome-based characterization of two prenylation steps in the assembly of the stephacidin and notoamide anticancer agents in a marine-derived Aspergillus sp. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132(36):12733–40.

Li S, Anand K, Tran H, Yu F, Finefield JM, Sunderhaus JD, McAfoos TJ, Tsukamoto S, Williams RM, Sherman DH. Comparative analysis of the biosynthetic systems for fungal bicyclo[2.2.2]diazaoctane indole alkaloids: the (+)/(−)-notoamide, paraherquamide and malbrancheamide pathways. Med Chem Commun. 2012;3(8):987–96.

Haas H. Fungal siderophore metabolism with a focus on Aspergillus fumigatus. Nat Prod Rep. 2014;31(10):1266–76.

Wiemann P, Lechner BE, Baccile JA, Velk TA, Yin WB, Bok JW, Pakala S, Losada L, Nierman WC, Schroeder FC, et al. Perturbations in small molecule synthesis uncovers an iron-responsive secondary metabolite network in Aspergillus fumigatus. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:530.

Yin WB, Baccile JA, Bok JW, Chen Y, Keller NP, Schroeder FC. A nonribosomal peptide synthetase-derived iron(III) complex from the pathogenic fungus Aspergillus fumigatus. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135(6):2064–7.

Wang Y, Gloer JB, Scott JA, Malloch D. Terezines A-D: new amino acid-derived bioactive metabolites from the coprophilous fungus Sporormiella teretispora. J Nat Prod. 1995;58(1):93–9.

Luo R, Liu B, Xie Y, Li Z, Huang W, Yuan J, He G, Chen Y, Pan Q, Liu Y, et al. SOAPdenovo2: an empirically improved memory-efficient short-read de novo assembler. GigaScience. 2012;1:18–8.

Tarailo-Graovac M, Chen N: Using RepeatMasker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. Current protocols in bioinformatics / editoral board, Andreas D Baxevanis [et al.] 2009, Chapter 4:Unit 4 10.

Cantarel BL, Korf I, Robb SM, Parra G, Ross E, Moore B, Holt C, Sanchez Alvarado A, Yandell M. MAKER: an easy-to-use annotation pipeline designed for emerging model organism genomes. Genome Res. 2008;18(1):188–96.

Holt C, Yandell M. MAKER2: an annotation pipeline and genome-database management tool for second-generation genome projects. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:491.

Korf I. Gene finding in novel genomes. BMC Bioinformatics. 2004;5:59.

Parra G, Bradnam K, Korf I. CEGMA: a pipeline to accurately annotate core genes in eukaryotic genomes. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(9):1061–7.

Stanke M, Waack S. Gene prediction with a hidden Markov model and a new intron submodel. Bioinformatics. 2003;19 Suppl 2:ii215–25.

Emanuelsson O, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H. Locating proteins in the cell using TargetP, SignalP and related tools. Nat Protoc. 2007;2(4):953–71.

Petersen TN, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H. SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nat Methods. 2011;8(10):785–6.

Sonnhammer EL, von Heijne G, Krogh A. A hidden Markov model for predicting transmembrane helices in protein sequences. Proc Int Conf Intell Syst Mol Biol. 1998;6:175–82.

Fu L, Niu B, Zhu Z, Wu S, Li W. CD-HIT: accelerated for clustering the next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(23):3150–2.

Weber T, Blin K, Duddela S, Krug D, Kim HU, Bruccoleri R, Lee SY, Fischbach MA, Muller R, Wohlleben W, et al. antiSMASH 3.0-a comprehensive resource for the genome mining of biosynthetic gene clusters. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(W1):W237–43.

Winnenburg R, Urban M, Beacham A, Baldwin TK, Holland S, Lindeberg M, Hansen H, Rawlings C, Hammond-Kosack KE, Kohler J. PHI-base update: additions to the pathogen host interaction database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(Database issue):D572–6.

Park J, Lee S, Choi J, Ahn K, Park B, Park J, Kang S, Lee YH. Fungal cytochrome P450 database. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:402.

Moktali V, Park J, Fedorova-Abrams ND, Park B, Choi J, Lee YH, Kang S. Systematic and searchable classification of cytochrome P450 proteins encoded by fungal and oomycete genomes. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:525.

Rawlings ND, Morton FR, Kok CY, Kong J, Barrett AJ. MEROPS: the peptidase database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(Database issue):D320–5.

Rawlings ND, Morton FR. The MEROPS batch BLAST: a tool to detect peptidases and their non-peptidase homologues in a genome. Biochimie. 2008;90(2):243–59.

Yin Y, Mao X, Yang J, Chen X, Mao F, Xu Y. dbCAN: a web resource for automated carbohydrate-active enzyme annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(Web Server issue):W445–51.

Cantarel BL, Coutinho PM, Rancurel C, Bernard T, Lombard V, Henrissat B. The Carbohydrate-Active EnZymes database (CAZy): an expert resource for Glycogenomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Database issue):D233–8.

Nierman WC, Pain A, Anderson MJ, Wortman JR, Kim HS, Arroyo J, Berriman M, Abe K, Archer DB, Bermejo C, et al. Genomic sequence of the pathogenic and allergenic filamentous fungus Aspergillus fumigatus. Nature. 2005;438(7071):1151–6.

Pel HJ, de Winde JH, Archer DB, Dyer PS, Hofmann G, Schaap PJ, Turner G, de Vries RP, Albang R, Albermann K, et al. Genome sequencing and analysis of the versatile cell factory Aspergillus niger CBS 513.88. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25(2):221–31.

Payne GA, Nierman WC, Wortman JR, Pritchard BL, Brown D, Dean RA, Bhatnagar D, Cleveland TE, Machida M, Yu J. Whole genome comparison of Aspergillus flavus and A. oryzae. Med Mycol. 2006;44(s1):9–11.

Lechner M, Findeiss S, Steiner L, Marz M, Stadler PF, Prohaska SJ. Proteinortho: detection of (co-)orthologs in large-scale analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:124.

Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(5):1792–7.

Talavera G, Castresana J. Improvement of phylogenies after removing divergent and ambiguously aligned blocks from protein sequence alignments. Syst Biol. 2007;56(4):564–77.

Kück P, Meusemann K. FASconCAT: Convenient handling of data matrices. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2010;56(3):1115–8.

Schmidt HA, Strimmer K, Vingron M, von Haeseler A. TREE-PUZZLE: maximum likelihood phylogenetic analysis using quartets and parallel computing. Bioinformatics. 2002;18(3):502–4.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Zhonglu Ren for technical support, and we also thank the two referees who took the time to review and help to improve our manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 31371290) to JL, a startup grant from Guangdong Province and Southern Medical University to JL, and a Tier I ARC grant from the ministry of Education of Singapore and Nanyang Technological University to ZXL.

Availability of data and materials

The assembled scaffolds supporting the conclusions of this article are available in GenBank under submission number LKBE00000000 and are accessible via the URL: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/?term=LKBE00000000. The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the additional file 2. Phylogenetic data for Fig. 2 (alignments and phylogenetic trees) have been deposited to TreeBase and are accessible via the URL: http://purl.org/phylo/treebase/phylows/study/TB2:S19617.

Authors’ contributions

JML, ZXL and XLH conceived the study. XLH created its design, performed bioinformatics analyses, and drafted the manuscript. ZXL and AC performed the experiments and genome sequencing preparations. JDZ performed annotation of the genomic sequences. All authors read, edited and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional files

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Statistics of the Aspergillus genomes used in this study. Table S2. Scaffolds greater than 100 kb in the A. westerdijkiae genome sequences. (XLSX 13 kb)

Additional file 2:

Sequences and coordinates of the predicted proteins and transcripts of A. westerdijkiae. (ZIP 10770 kb)

Additional file 3: Table S3.

Genome-wide alignment resulting from the MUMmer comparisons. (DOCX 21 kb)

Additional file 4: Table S4.

Putative secreted proteins involved in PHI, CAZy, Protease, and CYP450. (XLSX 134 kb)

Additional file 5: Table S5

Counts of the putative genes per CAZy family in the 9 genomes used in this study. Table S6. Counts of the putative genes per Plant Polysaccharide Degradation (PDD)-related CAZy family in the 9 genomes used in this study. Table S7. Functional annotation of the PDD-related genes (with orthologues) for A. westerdijkiae. Table S8. Functional annotation of the PDD-related genes (without orthologues) for A. westerdijkiae. Table S9. Counts of the putative genes involved in plant polysaccharide degradation in the nine Aspergillus species. (XLSX 79 kb)

Additional file 6: Table S10.

Putative proteases predicted by the batch Blast against the MEROPS database. (XLSX 53 kb)

Additional file 7: Table S11.

Putative secondary metabolism clusters. (XLSX 18 kb)

Additional file 8: Table S12.

Structural and functional annotations of the OTA biosynthesis-related clusters on scaffold14 of A. westerdijkiae. Table S13. Structural and functional annotations of the OTA biosynthesis-related cluster on scaffold45 of A. westerdijkiae. (DOCX 153 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, X., Chakrabortti, A., Zhu, J. et al. Sequencing and functional annotation of the whole genome of the filamentous fungus Aspergillus westerdijkiae . BMC Genomics 17, 633 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-016-2974-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-016-2974-x