Abstract

Ctenoluciidae is a Neotropical freshwater fish family composed of two genera, Ctenolucius (C. beani and C. hujeta) and Boulengerella (B. cuvieri, B. lateristriga, B. lucius, B. maculata, and B. xyrekes), which present diploid number conservation of 36 chromosomes and a strong association of telomeric sequences with ribosomal DNAs. In the present study, we performed chromosomal mapping of microsatellites and transposable elements (TEs) in Boulengerella species and Ctenolucius hujeta. We aim to understand how those sequences are distributed in these organisms’ genomes and their influence on the chromosomal evolution of the group. Our results indicate that repetitive sequences may had an active role in the karyotypic diversification of this family, especially in the formation of chromosomal hotspots that are traceable in the diversification processes of Ctenoluciidae karyotypes. We demonstrate that (GATA)n sequences also accumulate in the secondary constriction formed by the 18 S rDNA site, which shows consistent size heteromorphism between males and females in all Boulengerella species, suggesting an initial process of sex chromosome differentiation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Ctenoluciidae is a Neotropical freshwater fish family composed of two genera: Ctenolucius (C. beani and C. hujeta) and Boulengerella (B. cuvieri, B. lateristriga, B. lucius, B. maculata, and B. xyrekes) [1]. Those species have marked characteristics, such as their elongated snout and jaw, the reason why they are popularly known as “bicudas”, “agulhão”, or “pike characins”. They present the dorsal fin located on the back half of the body, which allows representatives of this family to jump out of the water to escape predators, attack small schools of fish, or capture insects that are close to the water [1,2,3]. .

Cytogenetic investigations in five of the seven valid Ctenoluciidae species revealed a conservation tendency in the diploid number of 36 chromosomes, and a strong association of telomeric sequences with 5 S and 18 S rDNA sites is suggested to be an ancestral characteristic of the family that precedes the divergence of Ctenolucius and Boulengerella [4, 5]. The accumulation of telomeric sequences associated with the rDNA locus can result in the formation of chromosomal hotspots, which are regions of the genome with a higher frequency of recombination that contribute to generate genetic incompatibilities between populations, which can lead to speciation. Such hotspots also enhance the dissemination of adaptative alleles into a population and can induce the differentiation of sex chromosomes [6,7,8,9,10]. The hotspot region (telomere + 18 S rDNA) in Boulengerella species may be identified by traditional Giemsa staining, given the secondary constriction, which also exhibits a size heteromorphism between men and females, indicating a potential XX/XY sex chromosome system [5]. Unlike Boulengerella species, which have simple 18 S rDNA sites, the hotspots in the cis-Andean species C. hujeta appear to have promoted the dispersion of the 18 S rDNA across the genome, resulting in several chromosomal pairs harboring this motif [4, 5]. However, no cytogenetic data for the trans-Andean species C. beani has been reported in the scientific literature, making it difficult to establish if the multiple sites for 18 S rDNA is a plesiomorphic or apomorphic feature of Ctenolucius.

The formation and maintenance of chromosomal hotspots can be influenced by several factors, including the association with simple sequence repeats (SSR) and Rex retroelements (Rex1, Rex3, and Rex6), which can move and insert in different regions of the genome [11,12,13,14]. Microsatellites are SSR that vary from one to six nucleotides, usually presented at telomeric and centromeric regions of autosomal and sex chromosomes in fish genomes, frequently associated with other repetitive DNA sequences [15]. On the other hand, Rex retroelements are non-LTR retrotransposons obtained from the fish model Xiphophorus (Teleostei, Poeciliidae) genome, being the Rex3 one of the first examples of a retrotransposon widespread in teleosts [14]. Those retroelements can be presented in specific chromosomal regions/pairs or widely spread among chromosomes, but especially in heterochromatin-rich regions: telomeres, pericentromeres, and centromeres [11, 12]. The mapping of repetitive sequences allowed a broader comprehension of the karyotypic evolution in several fish, such as in Erythrinus erythrinus (Characiformes, Erythrinidae), where the colocalization of Rex3, 5 S rDNA and (TTAGGG)n in the centromeric position of the large metacentric Y chromosome in karyomorph D was associated with processes that culminate in the differentiation of sex chromosomes [16]. In Cynodon gibbus (Characiformes, Cynodontidae), Rex6 sequences were associated with the heterochromatinization process of the W chromosome, and probably involved in the dispersion of the microsatellite motifs (CA)15 and (CAC)10, which are accumulated in a small heterochromatic portion of the W, which led to size variations of those sequences by ectopic recombination [17].

Considering that the association of repetitive DNAs in Ctenoluciidae seems to have had a fundamental role in the karyotypic evolution of the family, in the current study we carried out chromosomal mapping of microsatellite and transposable element (TE) sequences in Boulengerella species and Ctenolucius hujeta to understand how those sequences behave in these organisms’ genomes and their influence on the chromosomal evolution of Ctenoluciidae.

Results

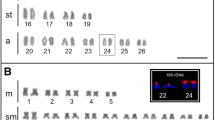

The chromosomal characteristics, such as the karyotypes and the fundamental numbers (FN) of the species investigated herein, are described in Sousa e Souza et al. (2017; 2021), following 2n = 36 chromosomes, FN = 72 for Boulengerella species, and 2n = 36 chromosomes, FN = 68 for C. hujeta.

Retroelements

The TEs Rex1, Rex3, and Rex6 presented a dispersed pattern with a small accumulation in some chromosomes, both in hetero- and euchromatic regions. Rex1 (Fig. 1) is present in all species herein analyzed with a dispersed pattern, except for B. lateristriga, where no signals were identified (data not shown). On the other hand, Rex1 was found in blocks preferentially at the terminal and centromeric regions of most chromosomes in C. hujeta.

Similarly, Rex3 was found dispersed in all chromosomal pairs, forming small blocks in the terminal, pericentromeric, and interstitial regions of some chromosomal pairs in all investigated species, as observed in pair 9 of B. cuvieri, pair 15 of B. lateristriga, pair 1 of B. lucius and B. maculata, and pair 12 of C. hujeta (Fig. 2).

Rex6 was presented preferentially in conspicuous blocks at the terminal region of pairs 1, 3, and 11 and in the interstitial region at pairs 1, 8, 9, 10, and 16 of B. cuvieri. In B. maculata, this TE accumulated in the centromeric region of several chromosomes, especially at pairs 1, 3, 6, 8, 10, 11, and 13. On the other hand, in B. lateristriga, this TE presented a dispersed pattern in all chromosomes (Fig. 3). Both B. lucius and C. hujeta do not presented any visible signals (data not shown).

Microsatellites

In B. lateristriga, B. maculata, and B. lucius, the microsatellite d(GATA)7 presented dispersed signals, with preferential accumulation in the telomeric portion of all chromosomes for both males and females, with some chromosomes also presenting interstitial and bitelomeric marks. We highlight the proximal mark in the short arms of pair 10 and the terminal region of long arms at pair 18, which in females seems to be duplicated, and in B. lucius, we highlight the species-exclusive centromeric signal on pair 04 (Fig. 4). On the other hand, the microsatellite d(GATA)7 is present only in pair 18, at the terminal position, in both sexes of B. cuvieri (Fig. 4).

For B. cuvieri, no FISH signals were found for the d(GAG)10 and d(CAA)10 microsatellites. The mapping of the motif d(CAC)10 revealed telomeric marks in five pairs, and d(CAT)10 showed telomeric signals in a single chromosome pair (Fig. 5). Moreover, d(GAG)10 and d(CAA)10 presented marks with preferential accumulation in terminal and centromeric regions of all chromosomes of B. lateristriga. Microsatellite d(CAC)10 presented terminal marks in two pairs, interstitial on the long arms of the other two pairs, one of which was pair 18 (Fig. 5, arrows). The mapping of the microsatellite d(CAT)10 in B. lateristriga did not provide detectable signals. (Fig. 5).

Chromosomal mapping of distinct microsatellite sequences in Boulengerella cuvieri, B. lateristriga, B. lucius and B. maculata. Metaphasic plates hybridized with the microsatellite probes d(GAG)10; d(CAA)10; d(CAC)10 and d(CAT)10 (red), revealing the distribution pattern on columns 1–4, respectively. Arrows indicate the position of chromosome pair 18

For B. lucius, the microsatellite d(GAG)10 presented telomeric marks in four pairs, while the microsatellite d(CAA)10 was not evidenced. The microsatellite d(CAC)10 revealed telomeric marks in almost all chromosomes, with accumulation in the secondary constriction of pair 18 (arrow), and d(CAT)10 showed telomeric marks in a single pair (Fig. 5). Finally, in B. maculata, the microsatellite d(GAG)10 presented bitelomeric marks in most chromosomes, with preferential accumulation at the terminal region of pair 18 (arrow). The microsatellite d(CAA)10 had no visible signals, while the motif d(CAC)10 revealed telomeric signals in five pairs, and d(CAT)10 presented telomeric marks in all chromosomes, in addition to interstitial signals on both long and short arms of a pair, and bitelomeric in three pairs (Fig. 5).

For C. hujeta, the microsatellite d(GATA)7 presented marks exclusively in pair 1 at the proximal region of short arms in the chromosomes of both males and females. The microsatellites d(GAG)10 and d(CAC)10 were not observed, and the motif d(CAA)10 showed telomeric marks in five chromosome pairs. The microsatellite d(CAT)10 presented telomeric marks in most chromosomes (Fig. 6).

Chromosomal mapping of distinct microsatellite sequences in Ctenolucius hujeta. Karyotype of males and females hybridized with microsatellites d(GATA)7 (upper section). Metaphasic plates hybridized with microsatellite probes d(GAG)10; d(CAA)10; d(CAC)10; d(CAT)10, respectively, showing the patter of those SSR at chromosomes (lower section)

Discussion

According to previous investigations, all Ctenoluciidae species exhibit a similar chromosomal macrostructure, where the conserved status of its diploid number is associated with a notable divergence at the genomic scale, especially regarding repetitive sequences [4, 5]. The current findings allowed us to follow the evolutionary relationships of the family and demonstrate that repetitive DNA sequences have distinct patterns of distribution and accumulation between ctenoluciids. The species-specific distribution of SSRs was observed between Boulengerella species and C. hujeta, with differences in the number, position, and intensity of hybridization signals for most analyzed motifs. Even in closely related clades or with recent divergence times, differences in the quantity and position of SSRs are common [18,19,20], as herein observed. Fossil records indicated that ctenoluciids diverged from other lineages at the end of the Miocene (1.8 Ma), probably after the emergence of the Andes Mountains, where large environmental changes occurred [1]. Although recent, such divergence time was enough to be visualized in the chromosomal background of repetitive sequence distribution since species differ in the predominance of several SSRs. For example, d(CAC)10 is shared by all Boulengerella species but absent in C. hujeta, while d(CAA)10 only had signals in B. lateristriga and C. hujeta (Figs. 5 and 6).

The high polymorphism rate of microsatellite sequences, estimated from 10− 2 to 10− 6loci per generation [18, 21, 22], can explain the different distribution patterns between C. hujeta and Boulengerella species. Microsatellite sequences can expand and contract as a result of ectopic recombination, replication slippage, transposition events or even association with transposable elements (TEs) by a process named “microsatellite seeding” [17, 18, 23, 24]. The dispersed pattern of Rex1, Rex3, and Rex6 and the accumulation at heterochromatic and euchromatic regions of chromosomes syntenic to SSRs suggests that microsatellite seeding is the mechanism responsible for the patterns observed in Ctenoluciidae representants and helps to explain the increase in those sequences in some species. The position of those retroelements in heterochromatic regions is described as an epigenetic mechanism that acts to avoid the excessive propagation of retroelements in the host genome [11, 25, 26], given that the position of those transposable elements in euchromatic regions may generate mutations that affect the levels of genetic expression and the patterns of DNA recombination or even interfere in the organization of genomic architecture [25, 27]. In this sense, we may infer that the position of those TEs in euchromatic regions may have facilitated chromosomal rearrangements such as inversions, deletions, duplications, and translocations, which culminate in karyotypic differences evidenced between Ctenolucius and Boulengerella [28, 29]. The correlation of environmental conditions and TEs is still a few explored research topic; however, studies have revealed that the distribution of those sequences is susceptible to environmental changes, such as increases or decreases in temperature [12, 30], exposure to pesticides [31] or even in response to stressful and polluted environments [32]. The same also occurs with ribosomal sequences, where differences in the accumulation and distribution of both 5 S and 18 S rDNA were observed inpreserved versus polluted environments [33].

In several fish species, TEs were found associated with ribosomal sequences, as observed in Hisonotus leucofrenatus [37], Erythrinus erythrinus [38], Astyanax bockmanni [35], Astyanax fasciatus [39], and several Ancistrus species [25]. This kind of transposition occurs given that codificant genes may form complexes with transposable elements and disperse in the species genomes [34,35,36]. Although not co-hybridized here, it is noteworthy that the secondary constriction formed by the NOR site in Boulengerella species (pair 18, according to Sousa e Souza et al., 2017) and C. hujeta (pairs 01, 09, and one of the homologs of pair 12, Sousa e Souza et al., 2021) have a small accumulation of Rex1 and Rex3. This same region also harbors (GATA)n sequences, in addition to corresponding to the telomeric region [4, 5]. Besides that, several other microsatellite motifs have been mapped in the secondary constriction, such as d(CAC)10, d(CAA)10, d(CAT)10, and d(GAG)10, suggesting that such region might be susceptible to rearrangements and the invasion of repetitive sequences. Considering that pair 18 in Boulengerella species is a proto-sex chromosome (Sousa e Souza et al., 2017), such an accumulation reinforces this previous hypothesis. Indeed, the microsatellite (GATA)n is highly conserved between eukaryotes and was isolated from the W chromosome of Caenophidia snakes [43,44,45]. It is frequently associated with sex chromosomes in mammals and some reptile and fish species [46,47,48,49,50,51]. In addition to its association with chromatin, transcription factors of heterochromatin, and formation factors, this motif is also present in autosomes, as already reported in some fish species [19, 20], presenting regulatory functions in the process of sex chromosome differentiation [19, 49]. The (GATA)n microsatellite is located in the same chromosomal pair that also carries the 5 S rDNA in Boulengerella species, with the accumulation of this SSR in the pericentromeric region of pair 10 in B. lateristriga, B. lucius, and B. maculata and in pair 4 of B. lucius. Considering that the first chromosome pair of all Boulengerella species and Lebiasina bimaculata, L. melanoguttata, and L. minuta are homeologs [52, 53] and carry at least one copy of the 5 S rDNA, this may correspond to the plesiomorphic carrier of the 5 S rDNA. Given that this region presents an accumulation of SSR and Rex retroelements, we can consider this region also a chromosomal hotspot. It is known that copy and paste events mediated by Rex retroelements may carry other ribosomal sequences, as already reported for Erythrinus erythrinus [16, 54], Pyrrhulina australis, Pyrrhulina aff. australis [55], and P. brevis [56].

The characterization of chromosomal hotspots might help the elucidation of the evolutionary pathways that led to differences in the karyotypes of Boulengerella species and C. hujeta. Although the synteny of telomeric, SSRs, Rex, and ribosomal sequences cannot be established by the current data, such an association might be further investigated. Notably, the pair that carry such sequences in Boulengerella species presents a size heteromorphism between males and females. It is worth noting that size heteromorphism in the secondary constriction, or of the nucleolar pair, is common in fish, occurring in both sexes and, for this reason, not associated with sex chromosomes [40,41,42]. However, in B. cuvieri, B. lateristriga, B. lucius, and B. maculata, this heteromorphism occurs only in the secondary constriction of males, a fact that led us to hypothesize that the accumulation might be a result of the arose of sex-specific sequences expressed in males with the absence of the secondary constriction in one of the pair 18 homologs. In this context, besides the investigation of synteny between the repetitive sequences abovementioned, more refined analysis such as comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) or even whole chromosome painting (WCP), may be useful tools to confirm the presence or absence of sex-specific sequences associated with pair 18 in Boulengerella species.

The conservation of diploid numbers with variation in the distribution of repetitive sequences is not an exclusive feature of Ctenoluciidae members. Other freshwater fish groups, such as the diploid lineages of Cyprinidae, share a common 2n = 50 but with divergence in repetitive DNA distribution (e.g [57]). . . Similarly, Carangidae marine fishes present a conserved 2n = 48, with variation in the proportion of bi-armed and acrocentric chromosomes [58]. For marine fishes, the maintenance of gene flow between large areas of species distribution is accepted as the main explanation for why the 2n is conserved [59]. However, such an explanation is evoked for groups where the divergence of the clades is old, which is not the case of ctenoluciids. In this scenario, it is possible that the recent divergence time was insufficient to generate large-scale changes in karyotype macrostructure, or at least those that can be visualized by classical cytogenetics. Indeed, molecular cytogenetics procedures allowed better access to the genome mainly in groups with conservative karyotypes [60], as in Ctenoluciidade, although small differences could already be observed in C-banding [5]. There is not a complete explanation for why some groups retain a conserved diploid number and others exhibit a wide variation. Some authors suggest that the plasticity of fish genomes allows structural variations without hampering their proper function or segregation [61]. While this question remains a mystery, increasing the knowledge on repetitive DNA distribution and possible evolutionary targets for karyotype organization allows a comprehensive view of Ctenoluciidae evolution.

Materials and methods

Species, sample points, and number of investigated specimens are described in Table 1. The samples herein analyzed correspond to the same ones previously described in Sousa e Souza et al. (2017).

In summary, fish were kept in aerated aquariums and, after 12 h of biological yeast stimulation [62], were euthanized in a 10% Eugenol solution, following the recommendations of the CONCEA Euthanasia Practice Guideline [63]. Then, mitotic metaphases were obtained from anterior kidney cells after in vitro treatment with colchicine [64, 65].

Probe preparation and FISH

The genomic DNA, used for all methodological steps, was extracted from muscle tissues fixed in 96% ethanol, according to the protocol established by the extraction kit Wizard® Genomic DNA Purification (Promega Corporation, Wisconsin, USA). The extracted DNA was subjected to electrophoresis in a 1% agarose gel and stained with Gel Red (Biotium) to check integrity. The following microsatellite sequences were used as probes: d(GATA)7, d(CAC)10, d(CAA)10, d(CAT)10 and d(GAG)10, since they correspond to standard microsatellite sequences used in fish cytogenomics studies [15]. These sequences were directly labeled with Cy3 in the 5’ end during synthesis by VBC-Biotech (Viena, Austria), following [66]. The retroelements Rex1, Rex3, and Rex6 were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from the Boulengerella lateristriga genome using the following primers: RTX1-F1 (5’-TTC TCCAGTGCCTTCAACACC) and RTX1-R1 (5’-TCCCTCAGCAGAAAGAGTCTGCTC) [67]; RTX3-F3 (5’- AACACCTTGGCTGCGCCTAG) e RTX3-R3 (5’-TTGAGG AACCGACGCGGATC) [68]; Rex6-Medf1 (5’-TAAAGCATACAT GGAGCGCCAC) and Rex6-Medf2 (5’-AGGAACATGTGTGCA GAATATG) [15].

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) was based on the protocol of [69], with some modifications. Slides were washed in PBS 1X solution for 5 min and fixed in 1% formaldehyde for 10 min. Next, the slides were washed again in PBS 1X solution for 5 min and dehydrated in an ethanol series (70, 85, and 100%) for 5 min at each concentration. After drying, the slides were denatured in formamide 70%/2xSSC at 70 °C and dehydrated in an ethanol series (70, 85, and 100%) for 5 min each. Next, the denaturation of the hybridization mix (1 µL of the labeled probe + 20 µL of DS solution per slide) occurred in a thermoblock for 10 min at 99 °C. After denaturation, the probe was applied to each slide and incubated in a moist chamber at 37 °C for 24 h to allow hybridization. Chromosomes were counterstained with DAPI (1,2 µg/mL), and the slides were mounted in an antifade solution (Vector, Burlingame, CA, USA).

Chromosomal analysis

At least 20 metaphases of each specimen were investigated to confirm the chromosomal distribution of retroelements Rex1, Rex3, and Rex6 and microsatellite sequences. Images were obtained using an Olympus BX51 (Olympus Corporation, Ishikawa, Japan) equipped with CoolSNAP. The best metaphases were captured, and karyotypes were assembled in Adobe Photoshop CS6 software. Chromosomes were classified as metacentric (m) or submetacentric (sm), following the classification proposed by [70], given the arm ratio.

Conclusion

Notably, the conservatism in Ctenoluciidae karyotypes is restricted only to the diploid number, and in this sense, we may infer that the diversity of SSR and Rex1, Rex3, and Rex6 retroelements evidenced in these species was essential to the formation of hotspot chromosomal regions. Such a region may have led to chromosomal rearrangements, as observed by the presence of acrocentric chromosomes, multiple sites of 18 S rDNA, chromosomal heteromorphisms, or even the transposition of 5 S rDNA sequences in the same genus, as observed in B. lucius when compared to other Boulengerella species.

The chromosomal hotspot formed by the association of several repetitive DNAs (e.g., 5 S/18S rDNA, (TTAGGG)n, d(GATA)7, d(CAC)10, d(CAA)10, d(CAT)10, d(GAG)10, and Rex sequences) in C. hujeta led to a dispersion of 18 S rDNA sites to pair 01 and to one of the homologs of pair 12, while in Boulengerella species, the same chromosomal hotspot at pair 18 induced the rise of a size heteromorphism in the secondary constriction between male and female that was associated with the syntenic accumulation of (GATA)n sequences, which may indicate an initial process of sex chromosome differentiation, which needs to be further investigated.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study were deposited in the National Amazon Research Institute (INPA) Fish Collection under the following numbers: Boulengerella (INPA-ICT 053246, 053247, 053248, 053249, and 053250) Ctenolucius hujeta (INPA-ICT 059514). https://portalcolecoesdb.inpa.gov.br/ictiologia/.

References

Vari RP. The neotropical Fish Family Ctenoluciidae (Teleostei: Ostariophysi: Characiformes): Supra and intrafamilial phylogenetic relationships, with a Revisionary Study. Smithsonian Institution; 1995.

Queiroz LJd T, Ohara G, VWM P, THdS, Zuanon J. Doria CRdC: Peixes do Rio Madeira, vol. 1; 2013.

Vari RP. Check list of freshwater fishes of South and Central America; 2003.

Sousa e Souza JF, Guimaraes E, Pinheiro-Figliuolo V, Cioffi MB, Bertollo LAC, Feldberg E. Chromosomal analysis of Ctenolucius hujeta Valenciennes, 1850 (Characiformes): a New Piece in the chromosomal evolution of the Ctenoluciidae. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2021;161(3–4):195–202.

Sousa e Souza JF, Viana PF, Bertollo LAC, Cioffi MB, Feldberg E. Evolutionary relationships among Boulengerella Species (Ctenoluciidae, Characiformes): Genomic Organization of repetitive DNAs and highly conserved Karyotypes. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2017;152(4):194–203.

Ashley T, Ward DC. A hot spot of recombination coincides with an interstitial telomeric sequence in the Armenian hamster. Cytogenet Genome Res 1993, 62.

Cherry JM, Blackburn EH. The internally located telomeric sequences in the germ-line chromosomes of Tetrahymena are at the ends of transposon-like elements. Cell 1985, 43.

Nergadze SG, Santagostino MA, Salzano A, Mondello C, Giulotto E. Contribution of telomerase RNA retrotranscription to DNA double-strand break repair during mammalian genome evolution. Genome Biol. 2007;8(12):R260.

Slijepcevic P. Telomeres and mechanisms of Robertsonian fusion. Chromosoma 1998, 107.

Wyman C, Blackburn EH. Tel-1 transposon-like elements of Tetrahymena thermophila are associated with micronuclear genome rearrangements. Genetics 1991, 129.

Carducci F, Barucca M, Canapa A, Biscotti MA. Rex Retroelements and Teleost genomes: an overview. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19(11).

Carducci F, Biscotti MA, Forconi M, Barucca M, Canapa A. An intriguing relationship between teleost Rex3 retroelement and environmental temperature. Biol Lett. 2019;15(9):20190279.

Volff J-N, Korting C, Schartl M. Multiple lineages of the Non-LTR Retrotransposon Rex1 with varying Success in Invading Fish genomes. Mol Biol Evol 2000, 17.

Volff J-N, Korting C, Sweeney K, Schartl M. The Non-LTR retrotransposon Rex3 from the Fish Xiphophorus is widespread among teleosts. Mol Biol Evol 1999, 16.

Cioffi MB, Bertollo LAC. Chromosomal distribution and evolution of repetitive DNAs in fish. In: Garrido-Ramos MA, editor Genome dynamics 2012, 7:197–221, Basel: Karger.

Cioffi MB, Martins C, Bertollo LAC. Chromosome spreading of associated transposable elements and ribosomal DNA in the fish Erythrinus erythrinus Implications for genome change and karyoevolution in fish. BMC Evol Biol 2010.

Pinheiro Figliuolo VS, Goll L, Ferreira Viana P, Feldberg E, Gross MC. First record on sex chromosomes in a species of the Family Cynodontidae: Cynodon gibbus (Agassiz, 1829). Cytogenet Genome Res. 2020;160(1):29–37.

Adams RH, Blackmon H, Reyes-Velasco J, Schield DR, Card DC, Andrew AL, Waynewood N, Castoe TA. Microsatellite landscape evolutionary dynamics across 450 million years of vertebrate genome evolution. Genome. 2016;59(5):295–310.

Pucci MB, Barbosa P, Nogaroto V, Almeida MC, Artoni RF, Scacchetti PC, Pansonato-Alves JC, Foresti F, Moreira-Filho O, Vicari MR. Chromosomal spreading of microsatellites and (TTAGGG)n sequences in the Characidium zebra and C. Gomesi genomes (Characiformes: Crenuchidae). Cytogenet Genome Res. 2016;149(3):182–90.

Pucci MB, Nogaroto V, Bertollo LAC, Orlando M-F, Vicari MR. The karyotypes and evolution of ZZ/ZW sex chromosomes in the genus Characidium (Characiformes, Crenuchidae). Comp Cytogenet. 2018;12(3):421–38.

Harr B, Zangerl B, Schlotterer C. Removal of microsatellite interruptions by DNA replication slippage: phylogenetic evidence from Drosophila. Mol Biol Evol 2000, 17.

Matsubara K, Nishida C, Matsuda Y, Kumazawa Y. Sex chromosome evolution in snakes inferred from divergence patterns of two gametologous genes and chromosome distribution of sex chromosome-linked repetitive sequences. Zoological Lett. 2016;2(1):19.

PB A. W. NM: Microsatellite variation and recombination rate in the Human Genome. Genet Soc Am 2000, 156.

Schug MD, Hutter; CM, Wetterstrand KA, Gaudette MS, Trudy FC, Mackay, Aquadro CF. The Mutation Rates of Di-, Tri- and tetranucleotide repeats in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Biol Evol 1998, 15.

Favarato RM, Ribeiro LB, Feldberg E, Matoso DA. Chromosomal mapping of transposable elements of the Rex Family in the Bristlenose Catfish, Ancistrus (Siluriformes, Loricariidae), from the amazonian region. J Hered. 2017;108(3):254–61.

Richards CL, Bossdorf O, Pigliucci M. What role does heritable epigenetic variation play in phenotypic evolution? BioScience 2010, 60(3):232–7.

Le Rouzic A, Capy P. The first steps of transposable elements invasion: parasitic strategy vs. genetic drift. Genetics. 2005;169(2):1033–43.

de Souza Se, Guimaraes JF, Pinheiro-Figliuolo E, Cioffi V, Bertollo MB, Feldberg LAC. Chromosomal analysis of Ctenolucius hujeta Valenciennes, 1850 (Characiformes): a New Piece in the chromosomal evolution of the Ctenoluciidae. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2021;161(3–4):195–202.

de Souza Se, Viana JF, Bertollo PF, Cioffi LAC, Feldberg MB. Evolutionary relationships among Boulengerella Species (Ctenoluciidae, Characiformes): Genomic Organization of repetitive DNAs and highly conserved Karyotypes. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2017;152(4):194–203.

Ferreira AMV, Marajó L, Matoso DA, Ribeiro LB, Feldberg E. Chromosomal mapping of Rex retrotransposons in Tambaqui (Colossoma macropomum Cuvier, 1818) exposed to three climate change scenarios. Cytogenet Genome Res 2019, 159.

Costa MDS, da Silva HCM, Soares SC, Favarato RM, Feldberg E, Gomes ALS, Artoni RF, Matoso DA. A perspective of Molecular Cytogenomics, Toxicology, and Epigenetics for the increase of heterochromatic regions and retrotransposable elements in Tambaqui (Colossoma macropomum) exposed to the Parasiticide Trichlorfon. Anim (Basel) 2022, 12(15).

da Silva FA, Correa Guimaraes EM, Carvalho NDM, Ferreira AMV, Schneider CH, Carvalho-Zilse GA, Feldberg E, Gross MC. Transposable DNA elements in amazonian fish: from genome enlargement to genetic adaptation to stressful environments. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2020;160(3):148–55.

da Silva FA, Feldberg E, Carvalho NDM, Rangel SMH, Schneider CH, Carvalho-Zilse GA, Gross MC. Effects of environmental pollution on the rDNAomics of amazonian fish. Environmental pollution 2019, 250.

Jiang N, Bao Z, Zhang X, Eddy2 SR, Wessler SR. Pack-MULE transposable elements mediate gene evolution in plants. Nature. 2004;431(7008):566–9.

Silva DM, Pansonato-Alves JC, Utsunomia R, Daniel SN, Hashimoto DT, Oliveira C, Porto-Foresti F, Foresti F. Chromosomal organization of repetitive DNA sequences in Astyanax bockmanni (Teleostei, Characiformes): dispersive location, association and colocalization in the genome. Genetica. 2013;141(7–9):329–36.

Zhang X, Eickbush MT, Eickbush TH. Role of recombination in the long-term retention of transposable elements in rRNA gene loci. Genetics. 2008;180(3):1617–26.

Ferreira DC, Oliveira C, Foresti F. Chromosome mapping of retrotransposable elements Rex1 and Rex3 in three fish species in the subfamily Hypoptopomatinae (Teleostei, Siluriformes, Loricariidae). Cytogenet Genome Res. 2011;132(1–2):64–70.

Cioffi MB, Martins C, Bertollo LAC. Chromosome spreading of associated transposable elements and ribosomal DNA in the fish Erythrinus erythrinus. Implications for genome change and karyoevolution in fish; 2010.

Pansonato-Alves JC, Serrano ÉA, Utsunomia R, Scacchetti PC, Oliveira C, Foresti F. Mapping five repetitive DNA classes in sympatric species of Hypostomus (Teleostei: Siluriformes: Loricariidae): analysis of chromosomal variability. Rev Fish Biol Fish. 2013;23(4):477–89.

Cerqueira AV, Lemos B. Ribosomal DNA and the Nucleolus as keystones of Nuclear Architecture, Organization, and function. Trends Genet. 2019;35(10):710–23.

Kasahara S. Introdução a Pesquisa em Citogenética de Vertebrados; 2009.

Mondin M, Janay A, Santos-Serejo LRM, Aguiar-Perecin. Karyotype characterization of Crotalaria juncea (L.) by chromosome banding and physical mapping of 18S-5.8S-26S and 5S rRNA gene sites. 2007.

Epplen JT, Mccarrey JR, Sutou SH, Ohno S. Base sequence of a; cloned snake W-chromosome DNA fragment and identification of a male-specific putative mRNA in the mouse. Genetics 1982, 79.

Traldi JB, Blanco; DR, Vicari MR, JdF M, RF LRLA, Moreira-Filho O. Physical mapping of (GATA)n and (TTAGGG)n sequences in species of Hypostomus (Siluriformes, Loricariidae). J Genet 2013, 92.

Ziemniczak K, Traldi JB, Nogaroto V, Almeida MC, Artoni RF, Moreira-Filho O, Vicari MR. In situ localization of (GATA)n and (TTAGGG)n repeated DNAs and w sex chromosome differentiation in Parodontidae (Actinopterygii: Characiformes). Cytogenet Genome Res. 2014;144(4):325–32.

Mazzoleni S, Augstenova B, Clemente L, Auer M, Fritz U, Praschag P, Protiva T, Velensky P, Kratochvil L, Rovatsos M. Sex is determined by XX/XY sex chromosomes in Australasian side-necked turtles (Testudines: Chelidae). Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):4276.

Rovatsos M, Johnson Pokorna M, Altmanova M, Kratochvil L. Mixed-Up Sex Chromosomes: Identification of Sex Chromosomes in the X1X1X2X2/X1X2Y System of the Legless Lizards of the Genus Lialis (Squamata: Gekkota: Pygopodidae). Cytogenet Genome Res. 2016;149(4):282–9.

Singh L, I FP, Jones KW. Satellite DNA and evolution of sex chromosomes. Chromosoma 1976, 59.

Subramanian S, Mishra RK, Singh L. Genome-wide analysis of bkm sequences (GATA repeats): predominant association with sex chromosomes and potential role in higher order chromatin organization and function. Bioinformatics. 2003;19(6):681–5.

Viana PF, Ezaz T, de Bello Cioffi M, Jackson Almeida B, Feldberg E. Evolutionary insights of the ZW Sex chromosomes in snakes: a New Chapter added by the amazonian puffing snakes of the Genus Spilotes. Genes (Basel) 2019, 10(4).

Viana PF, Ezaz T, de Bello Cioffi M, Liehr T, Al-Rikabi A, Goll LG, Rocha AM, Feldberg E. Landscape of snake’ sex chromosomes evolution spanning 85 MYR reveals ancestry of sequences despite distinct evolutionary trajectories. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):12499.

Leite PPM, Sassi FMC, Marinho MMF, Nirchio M, Moraes RLRd, Toma GA, Bertollo LAC. Cioffi MdB: tracking the evolutionary pathways among Brazilian Lebiasina species (Teleostei: Lebiasinidae): a chromosomal and genomic comparative investigation. Neotropical Ichthyol 2022, 20(1).

Sassi FMC, Oliveira EA, Bertollo LAC, Nirchio M, Hatanaka T, Marinho MMF, Moreira-Filho O, Aroutiounian R, Liehr T, Al-Rikabi ABH et al. Chromosomal evolution and Evolutionary relationships of Lebiasina Species (Characiformes, Lebiasinidae). Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20(12).

Martins NF, Bertollo LAC, Troy WP, Feldberg E, de Souza Valentin FC, de Bello Cioffi M. Differentiation and evolutionary relationships in Erythrinus erythrinus (Characiformes, Erythrinidae): comparative chromosome mapping of repetitive sequences. Rev Fish Biol Fish. 2012;23(2):261–9.

de Moraes RLR, Bertollo LAC, Marinho MMF, Yano CF, Hatanaka T, Barby FF, Troy WP, Cioffi MB. Evolutionary relationships and Cytotaxonomy considerations in the Genus Pyrrhulina (Characiformes, Lebiasinidae). Zebrafish. 2017;14(6):536–46.

de Moraes RLR, Sember A, Bertollo LAC, de Oliveira EA, Rab P, Hatanaka T, Marinho MMF, Liehr T, Al-Rikabi ABH, Feldberg E, et al. Comparative cytogenetics and Neo-Y formation in small-sized fish species of the Genus Pyrrhulina (Characiformes, Lebiasinidae). Front Genet. 2019;10:678.

Yang L, Sado T, Hirt MV, Pasco-Viel E, Arunachalam M, Li J, Wang X, Freyhof J, Saitoh K, Simons AM, et al. Phylogeny and polyploidy: resolving the classification of cyprinine fishes (Teleostei: Cypriniformes). Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2015;85:97–116.

Rodrigues MM, Baroni S, Almeida-Toledo LF. Karyological characterization of four Marine Fish species, Genera Trachinotus and Selene (Perciformes: Carangidae), from the Southeast Brazilian coast. Cytologia. 2007;72:95–9.

Molina WF. Chromosomal changes and stasis in marine fish groups. In: Pizano E, Ozouf-Costaz C, Foresti F, Kapoor BG: Fish Cytogenetics. Boca Raton, CRC, 69–110.

Artoni RF, Castro JP, Jacobina UP, Lima-Filho PA, Costa GWWF, Molina WF. Inferring diversity and evolution in fish by means of integrative molecular cytogenetics. Sci World J. 2015, 365787.

Venkatesh B. Evolution and diversity of fish genomes. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2003;13(6):588–92.

Oliveira C, Almeida-Toledo L, Foresti F, Britski H, Toledo-Filho S. Chromosome formulae of neotropical freshwater fishes. Revista Brasileira De Genética 1988, 11.

CONCEA. Diretrizes Da prática De eutanásia do CONCEA. MINISTÉRIO DA CIÊNCIA TECNOLOGIA E INOVAÇÃO 2013:50.

Bertollo LAC, Cioffi MdB, Moreira-Filho O. Direct chromosome preparation from freshwater teleost fishes. Fish Cytogenetic Techniques (Chondrichthyans and Teleosts); 2015.

Gold JR, YC LI, NS SHIPLEY. POWERS PK: improved methods for working with fish chromosomes with a review of metaphase chromosome banding. Jaurnal Fish Biology 1990, 37.

Kubat Z, Hobza R, Vyskot B, Kejnovsky E. Microsatellite accumulation on the Y chromosome in Silene latifolia. Genome. 2008;51(5):350–6.

Volff JN, Korting C, Froschauer A, Sweeney K, Schartl M. Multiple lineages of the Non-LTR Retrotransposon Rex1 with varying Success in Invading Fish genomes. Mol Biol Evol 2000:1673–84.

Volff JN, Korting C, Froschauer A, Sweeney K, Schartl M. The Non-LTR retrotransposon Rex3 from the Fish Xiphophorus is widespread among teleosts. Mol Biol Evol 1999:1427–38.

Pinkel D, Straume T, Gray JW. Cytogenetic analysis using quantitative, high-sensitivity, fluorescence hybridization. Genetics 1986, 83.

Levan A, Fredga K, Sandberg AA. Nomenclature for centromeric position on chromosomes. Hereditas. 1964;52(2):201–20.

Funding

This study was supported by the Brazilian agencies National Amazon Research Institute (INPA), Postgraduate Program in Genetics, Conservation and Evolutionary Biology (PPG GCBEv), and Center for Studies of Adaptation to Environmental Changes in the Amazon (INCT ADAPTA II, FAPEAM/CNPq 573976/2008-2). This work was carried out with the support of the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - Brazil (CAPES) - Financing Code 001, and José Sousa received a study grant from the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES). This work was carried out with support from the Amazonas State Research Support Foundation (FAPEAM) - Stricto Sensu Postgraduate Institutional Support Program (FAPEAM-POSGRAD). E Feldberg was also the recipient of a CNPq fellowship (process 301886/2019-9).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

José Sousa and Eliana Feldberg conceived and designed the research. José Sousa conducted the experiments. José Sousa, Marcelo Cioffi and Eliana Feldberg contributed new analytical tools. José Sousa, Marcelo Cioffi and Eliana Feldberg analyzed the data. Erika Guimarães; Vanessa Figliuolo; Marcelo Cioffi; Simone Cardoso; Francisco Sassi and Eliana Feldberg wrote the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Statement of ethics

The experiments followed ethical and anesthesia conducts in accordance with the Ethics Committee for Animal (CEUA) of the National Institute of Amazon Research under protocol number 033/2020.

Consent for publication

The manuscript does not contain data from any individual.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

de Sousa e Souza, J.F., Guimarães, E.M.C., Figliuolo, V.S.P. et al. Chromosomal mapping of repetitive DNA and retroelement sequences and its implications for the chromosomal evolution process in Ctenoluciidae (Characiformes). BMC Ecol Evo 24, 72 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-024-02262-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-024-02262-x