Abstract

This study analyzes the mechanisms by which short-time work (STW) schemes affect firm’s employment adjustments, using establishment-level data during the Great Recession from Japan. The findings show that STW leads to a decrease in both hiring and separations, with no significant positive effect on net employment. The observed curtailed hiring can be explained within the context of how STW promotes labor hoarding. STW encourages firms to maintain redundant employment by subsidizing the costs of labor hoarding. The excess labor surplus in firms adopting STW diminishes the incentive to recruit new workers in anticipation of the recovery period. Furthermore, as firms generally lack the motivation to hoard marginal workers, STW may exacerbate job security disparities between regular and marginal workers. These findings have important implications for policy evaluation, emphasizing the need for a comprehensive understanding of the potential adverse consequences of STW on labor market entrants and marginal workers.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Just like many other major industrial economies, Japan experienced substantial setbacks due to the sharp declines in trade and production triggered by the collapse of Lehman Brothers and the subsequent financial crisis in the United States. During the first quarter of 2009, the real GDP contracted by 8.4% (annual rate), relative to the preceding year, while the industrial production index witnessed a 34% decline in February 2009 compared to May 2008. The contraction in output during the Great Recession surpassed that of previous economic downturns, as depicted in the top two panels of Fig. 1. Surprisingly, the impact of this significant output drop on the labor market was comparatively modest. Despite the unemployment rate rising to 5.5% in July 2009, up from 3.8% in October 2008, the recovery proved relatively swift, as illustrated in the bottom panel of Fig. 1. The unemployment rate commenced its descent in the fourth quarter of 2009, and by the conclusion of 2011, it had returned to the mid-4% range, closely aligning with the natural rate.

Changes of real GDP, indices of industrial production for all industries, and unemployment rate during the recessions in recent years. Note: The dates of the recessions are specified by the turning points of the growth of detrended log real GDP. The four periods of the recessions are 1991Q2–1994Q2, 1997Q1–1999Q1, 2001Q1–2002Q1, and 2008Q1–2009Q4. The quarter immediately following the Lehman Brothers’ bankruptcy (2008Q4) is denoted by a circled marker.

Comparing Japan’s performance with that of other countries during the Great Recession, Japan fared well as noted by Steinberg and Nakane (2011) and others. Various perspectives have emerged to explain this resilience. Drawing upon comparisons with the recession in 1997–1998, Hijzen et al. (2015) find that it is a major shift in the adjustment of labor input away from employment to average hours that greatly lessened the negative impact on employment. In contrast, Pissarides (2013), employing a simple Okun type regression, identifies a remarkably large negative prediction residual during the bottom of Great Recession, hovering around −2% in Japan. He suspects that labor hoarding, a phenomenon wherein firms maintain a workforce beyond the optimal level in response to temporary shocks, aiming to economize on the costs associated with firing, hiring, and employee training, may account for this negative residual in Japan’s case. Steinberg and Nakane (2011), on the other hand, attribute the relatively mild employment response in Japan to wage flexibility. Through international macro comparisons, they posit that wage flexibility serves as a substitute for employment flexibility, elucidating the comparatively modest impact of the Great Recession on employment in Japan.

Yet they also consider that the heavy dose of government subsidies aimed at supporting and encouraging work hour reduction played a pivotal role in mitigating the negative effect of a sharp output decline on employment. In response to the onset of the Great Recession in the global economy, the Japanese government demonstrated an unusually prompt reaction by implementing a range of emergency measures. One notable intervention involved a significant enhancement of the Employment Adjustment Subsidy, the short-time work (STW) scheme in Japan, to prevent downward employment adjustments. The eligibility criteria were significantly relaxed, and the subsidy amount was substantially increased in December 2008, right after the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers.

In this paper, I analyze carefully the effect of the Japanese STW on employment flows. To achieve this, I develop an endogenous treatment model for estimating the influence of STW on the employment adjustments within an establishment. The challenge in studying the effects of STW lies, at least partially, in the potential dependence of how STW influences employment adjustments on establishment-specific characteristics. These characteristics, including management policies, employee composition, and the substitutability between the number of employees and work hours, are not directly observable to researchers with limited information. To address this, I employ a fixed-effects model that allows for establishment-specific effects using micro panel data of establishments. To counteract potential self-selection bias, I treat the take-up of STW as an endogenous decision.

This paper contributes to the literature by being among the first analysis to utilize micro panel data of establishments for an in-depth examination of the impact of STW on employment adjustments in Japan during the Great Recession. The utilization of this data allows for the direct identification of business conditions, employment turnovers, and STW take-up for each establishment, facilitating the incorporation of establishment-specific effects. Furthermore, partly due to the limitations of data, past studies focus mainly on how STW influences layoffs or unemployment rate. However, with the access to the data on both the hiring and separations of establishments, I gain deeper insights into the mechanisms through which STW influences a firm’s employment decisions.

I find that the estimated treatment effects of the STW in Japan on labor turnovers are −1.4% (on an annual basis) for separations and −3.1% for hiring. Consequently, the overall effect of the subsidy on employment is −1.7%, although this outcome lacks statistical significance. The estimation results reveal that STW diminishes both hiring and separations, and there is insufficient evidence supporting a positive impact on employment. The observed reduction in hiring can be explained by understanding how STW encourages labor hoarding. In order to economize on turnover costs, firms may opt to decrease work hours instead of reducing the workforce in response to temporary shocks (labor hoarding). However, labor hoarding incurs costs, including leave allowances that firms must compensate workers for the reduced work hours. Frictions such as financial constraints may constrain labor hoarding below its efficient level. By subsidizing the costs associated with the reduction in work hours, STW enables firms to achieve a higher level of labor hoarding than they would accomplish without STW.

The excess labor surplus in firms taking up STW diminishes the incentive to recruit new workers in anticipation of the recovery period. Consequently, STW may undermine employment prospects for recent graduates, thereby amplifying the scarring effect. Moreover, through promoting labor hoarding, STW has the potential to exacerbate the disparity in job security between regular and marginal workers, as firms, in general, lack the motivation to hoard marginal workers.Footnote 1 In sum, STW may redirect adjustments and risk from existing regular workers onto labor market entrants and marginal workers through subsidizing labor hoarding.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews previous studies on the STW in Japan. Section 3 describes a comprehensive account of the data. Section 4 presents the base model and the estimation results. Section 5 discusses the evaluation of the Japanese STW. Finally, Sect. 6 concludes the study.

2 Past studies on the STW in Japan

The STW in Japan, known as Employment Adjustment Subsidy (Koyō Chōsei Joseikin), is a subsidy program designed to support employers compelled to downsize due to fluctuations in business conditions or other economic factors. This program extends financial support by subsidizing a portion of the fringe benefits or compensations allocated to employees experiencing reduced work hours or days. By subsidizing the cost associated with the reduction in the work hours of existing employees, the Japanese STW aims to incentivize firms to avoid layoffs, thereby stabilizing employment against temporary shocks. The program is funded by the national employment insurance program in Japan, the primary and mandatory unemployment insurance system applicable to establishments and their employees meeting specified criteria. As of 2010, the employment insurance coverage rate for regular workers reached 99.5%. In stark contrast, the coverage rate for marginal workers stood at a mere 65.2%, resulting in the exclusion of more than 30% of marginal workers from STW payment eligibility.Footnote 2

Earlier studies on the policy effect of the STW in Japan relied mostly on macroeconomic analysis at industry or prefecture level due to the lack of suitable micro data. In addition, because STW was only applied to establishments in designated industries until 2001, research interest has been placed on whether STW prevents the exit of inefficient establishments and delays the transformation of the industrial structure. Among them, Chuma et al. (2002), using the prefectural data from 1975 to 1999 to investigate the impact of STW on employment adjustments, fail to detect any significant impact of STW on regional variations in the unemployment rate. In contrast, Kambayashi (2012) developed a search model to ascertain the relationship between STW and the Beveridge curve. This model was subsequently estimated utilizing data on active job openings and applications. The result suggests that STW may have mitigated the escalation of the unemployment rate.

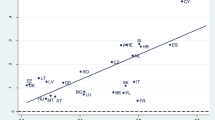

The expanded utilization of STW during the Great Recession across multiple OECD countries, including Japan, offers an opportunity to examine its impact on employment. Using data gathered from these countries, rigorous cross-country panel analysis has been diligently undertaken to identify the relationship between STW take-up rate and employment outcome by exploiting the variations in STW take-up rates across countries and over time. Among them, Hijzen and Venn (2011) conduct a study of STW using data for 19 OECD countries including Japan, wherein they estimate a cross-country regression and find that STW significantly reduced the negative impact of the severe recession on employment. Cahuc and Carcillo (2011), expanding the data to 25 OECD countries, also obtain a similar estimation result indicating a significant effect of STW in mitigating the negative impact of output decline on employment. In Hijzen and Venn (2011), the estimated impact of STW on employment amounts to saving approximately 0.4 million jobs in Japan, while Boeri and Brueckner (2011) suggest a comparatively smaller impact, saving around 10,000 jobs. Hijzen and Martin (2013) extend the estimation period up to 2010, focusing on the dynamic effects of STW over time. Assuming symmetric impacts during downturns and recoveries, they observe that although about 0.4 million jobs were preserved in Japan during the crisis, the continued use of STW during the subsequent recovery exerted a negative influence, resulting in a cumulative negative impact of approximately 15,000 jobs by the end of 2010. A consistent finding across these studies is that the estimated impact on employment for temporary workers in the sample economies is either statistically insignificant or quantitatively very small.

These macroeconomic evaluations, however, do not shed much light on how STW impacts the employment adjustments within a firm. Theoretical studies provide valuable insights in this realm. Van Audenrode (1994) illustrates that STW is likely to shift the process of labor adjustment from adjustments through layoffs to adjustments through variations in working time using an implicit contract model. Balleer et al. (2016) demonstrate that STW diminishes layoffs and augments hiring through a search and matching model. However, they note that temporary discretionary changes in the eligibility criteria of STW, crafted to address severe economic downturns, prove entirely ineffective as they fail to influence future expectations of firms. Cooper et al. (2017), employing a search and matching model that assumes the endogenous response of vacancy-filling probability to employment levels, reveal that although STW lessens layoffs, a decrease in the unemployment rate escalates search costs, thereby reducing hiring in expanding firms, ultimately undermining the labor market’s allocative efficiency and leading to significant output losses. Griffin (2010), focusing on the STW in Japan and utilizing a partial equilibrium model, establishes that STW curbs employment volatility in firms responding to business cycles. Consequently, while firms increase the number of unutilized employees and maintain higher average establishment-level employment during economic downturns, they spend less time and money on hiring in favorable conditions.

While theoretical studies consistently confirm STW’s efficacy in reducing layoffs, empirical studies utilizing micro data present inconclusive findings regarding this impact. The divergence in findings arises from the inherent challenge of mitigating selection bias resulting from firms’ self-selection into STW take-up. Bellmann et al. (2012) (Germany), using an IV difference-in-difference method, discover no significant evidence regarding the effect of STW on employment adjustments. Similarly, Kruppe and Scholz (2014) (Germany) and Calavrezo et al. (2010) (France), employing a propensity score matching approach, find no positive effects of STW on employment. In contrast, Boeri and Brucker (2011) (Germany), investigating the same data as Bellmann et al. (2012) but employing firms’ prior STW experience as an instrumental variable to address self-selection concerns, find that STW did contribute to reducing job losses during the Great Recession. Recent studies, such as Giupponi and Landais (2022) (Italy), Cahuc et al. (2021) (France), and Kopp and Siegenthaler (2021) (Switzerland), employ identification strategies leveraging exogenous eligibility rules or regional/departmental approval rates of STW, all of which affirm the positive effects of STW on employment.

The Japan Institute of Labour Policy and Training (JILPT) (2017) collects the first comprehensive analyses on the Japanese STW using establishment-level micro data. Three chapters investigate the STW’s influence on worker flows (hires and separation) employing estimation methods designed to address the self-selection problem. Ariga and Kuo in Chapter 5 utilize an endogenous switching regression model, while Ka in Chapter 6 employs a propensity score matching approach, and Zhang in Chapter 7 utilizes an instrumental variable approach. Despite variations in estimation techniques and sample selections, Chapters 5 and 7 find at least some negative impact on separations. Meanwhile, Chapters 5 and 6 both identify a significant negative impact on hiring.

This paper is based on Chapter 5 by Ariga and Kuo from JILPT (2017). While utilizing the same dataset, a Heckman-type two-step endogenous treatment model is employed to address the self-selection issue. Particular emphasis is placed on the interpretation of the main finding on reduced hiring and delving into the policy evaluation of STW. The impact of STW on hiring has remained relatively underexplored in prior research. Nonetheless, as demonstrated by Bellmann et al. (2012), over half of the increased job losses in STW recipient establishments during the Great Recession in Germany were attributable to reduced hiring. In addition, although STW is not the focus of the paper, Hijzen et al. (2015), undertaking a comparative analysis of the recessions in Japan during 2008–2009 and 1997–1998, find that compared to the 1997–1998 recession, the response to output decline during the Great Recession were highly muted, more so in hiring than in separations. These outcomes imply a conceivable scenario wherein the augmented utilization of STW could significantly affect the hiring behavior of firms.

3 Data

3.1 Data source and variable construction

This paper utilizes two sets of establishment-level data. The first set, referred to as the “Survey,” is obtained from a survey conducted by JILPT in June and July of 2013. The purpose of this survey is to investigate the utilization of STW at recipient establishments during the relevant period and compare it with non-recipients. It randomly selected 7500 establishments from the entirety of those utilizing STW between December 2008 and March 2013. To establish a control group, an equivalent number of establishments (7500) which did not use STW in this period were selected based on stratified sampling by prefecture, industry, and size of the establishment. After data cleaning, there are 5945 valid replies, including 3479 recipients and 2466 non-recipients.Footnote 3 The Survey collected information about changes in operation level,Footnote 4 employment, hiring, job separation, and other indicators related to production and employment changes on a fiscal year basis. The Survey also includes information regarding establishment characteristics and the types of employment adjustment methods employed during past economic downturns. It is important to note that these responses were retrospective answers compiled in mid-2013.

The second set, referred to as the “Admin,” is the data compiled by the administrative body of the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) in charge of the STW program.Footnote 5 The Admin contains monthly records of 30,000 establishments, including 14,711 recipients and 15,289 non-recipients, covering the period from April 2008 to March 2013.Footnote 6 The selection of recipients and non-recipients was conducted through stratified sampling from establishments that employed the STW and those that did not respectively. Stratification was performed based on prefecture, industry, and the size of the establishment. This dataset includes information on the number of employees covered by employment insurance in each establishment, their inflows, outflows, and detailed information on the use of STW on a monthly basis. However, because the data is collected for the administrative purposes of employment insurance, it lacks other crucial information necessary for investigating the characteristics of employment adjustments during the sample period. Specifically, there is no information regarding employment composition, work hours, and measures of production or sales on which the STW eligibility requirement is imposed. Additionally, it should be noted that the Admin data does not include employees who are not covered by employment insurance, mainly marginal workers. Hence we have no way of knowing the ramifications of STW on their fates. This limitation of the data necessitates caution in interpreting the estimation results.

The Survey and Admin are combined into a yearly panel data using the common identification numbers assigned to each establishment. The outcome variables are hiring rate, separation rate, and rate of employment change, all measured on an annual basis. These variables are computed using data on the monthly inflow and outflow of employees covered by employment insurance in each establishment. The take-up of STW is represented with a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if an establishment receives STW subsidy for at least one month in a year, and 0 otherwise.Footnote 7,Footnote 8 Both the outcome variables and the STW dummy variable are constructed using the Admin. The constructed data set follows a fiscal year basis (from April to March of the next year), and the sample period covers FY2008 to FY2012.

The most crucial control variable is the business condition of an establishment. Since the Admin data does not include monthly production or sales figures, I use the matched survey results on annual changes in the operation level as a proxy for this unobservable variable. Other control variables encompass the yearly average of the number of employment insurance covered employees, which serves as a proxy for establishment size, the average share of STW recipients in the industry to which an establishment belongs, the share of regular workers among directly hired employees, the year of establishment, and the industry and regional affiliations of an establishment. The first two control variables are constructed based on the Admin data, while the remaining variables are derived from the Survey. After eliminating samples with missing observations for these key variables, the sample consists of 4,689 establishments, resulting in 22,610 observations in the combined panel data.

It is important to note that the operation level, a crucial control variable in my analysis, represents annual data obtained from the Survey conducted in mid-2013. Due to the retrospective nature of the questionnaire, it is likely to contain recall errors. In contrast, the outcome variables and the dummy variable indicating the use of STW are constructed from the Admin data, suggesting a lower likelihood of similar data contamination. Nonetheless, the outcome variables (hiring rate, separation rate, and rate of employment change) also face challenges, as the inflow and outflow of employment insurance covered employees may not precisely reflect actual hirings and separations. For instance, the merging and division of establishments can lead to inflow and outflow without corresponding genuine hiring and separation activities. Another scenario involves temporary assignments to other firms (syukko). Fortunately, merging and division are infrequent in the Japanese context, and temporary assignments are not prevalent in small and medium-sized firms. Given that 88.9% of establishments in my sample consist of fewer than 50 employees, the consequential impact of these cases on the overall results is limited. There is also the possibility of incumbents newly covered by employment insurance being counted as new hires. Given that the Japanese government relaxed the criteria for employment insurance coverage twice during the sample period, there is a potential for an upward bias in the hiring rate.Footnote 9 However, surveys conducted by the MHLW indicate that the coverage rate of marginal workers, who are most affected by the relaxation of the criteria, experienced a modest shift of merely 5 percentage points between 2007 and 2010. Thus, the upward bias in the hiring rate is expected to be minimal.

An additional data limitation arises from the survey’s inability to encompass establishments that went out of business within the survey period (2008.4–2013.3), potentially introducing survivorship bias.Footnote 10 Chapter 6 of JILPT (2017) scrutinizes the Admin and reveals that among STW recipients, 8.4% underwent closure during the same period, in contrast to 19.8% of non-recipients. Moreover, an examination of employment trends indicates that STW recipients retain more employment compared to non-recipients when establishments that went out of business are included in the sample. Conversely, the trend reverses when establishments that went out of business are excluded. These two observations suggest that STW may contribute to the continuity of establishments. However, the preservation of establishments in adverse conditions through STW is associated with a negative impact on the overall employment levels among recipients. The exclusion of establishments that have undergone closure from the sample precludes an examination of the employment retention effects of STW in mitigating business closures, potentially resulting in an underestimation of its effect.

Finally, it is worth reiterating that the Admin data only covers establishments and employees who are covered by employment insurance. Given the smaller coverage of marginal employees, the data may over-represent regular employees, potentially leading to an underestimation of the hiring and separation rates in establishments that extensively employ marginal workers. Additionally, the annual data on the operation level of establishments may not precisely correspond to the monthly measure used to determine STW eligibility. The lack of precise information on establishment eligibility makes it challenging to address self-selection biases in STW take-up.

3.2 Summary statistics

Table 1 presents the summary statistics for the key selected variables. The mean value of the STW dummy variable indicates a sharp increase in STW take-up during FY2009. Throughout the survey period, the mean rate of employment change remains positive, although the values for FY2009 and FY2012 are lower primarily due to a decline in the hiring rate. The impact of the Great Recession on the separation rate appears somewhat attenuated in FY2009 because the bottom months of the recession are included in FY2008. The percentage change in operation level is lowest in FY2009 and increases afterwards. As previously mentioned, approximately half of the sampled establishments in the Survey is establishments which had received STW at least once during the survey period, hence resulting in a high mean value for the STW dummy variable. In the midst of the Great Recession in 2009, the mean value is approximately 0.47.

Table 2 provides a comparison between STW recipients and non-recipients. In comparison to non-recipients, STW recipients exhibit lower hiring and separation rates. The average rate of employment change for recipients is negative, whereas it is a small positive value for non-recipients. These differences align with the disparities observed in the annual change of operation level: recipients have a negative average, whereas non-recipients have a positive average. Furthermore, we observe that recipients, on average, employ a greater number of regular employees, have larger establishment size, are older in age, and are more likely in the manufacturing sector.

Two distinct characteristics of this sample emerge from Tables 1 and 2. Firstly, there is a notable feature of small establishment size, with an average of approximately 30 employees. This mirrors the prevalent presence of small and medium-sized establishments in Japan, where those with less than 10 employees constitute about 80% of the total according to a government census. The second characteristic is the high percentage of manufacturing establishments. The pronounced representation of manufacturing in STW recipients reflects the substantial impact experienced by Japan’s manufacturing sector due to the decline in exports to countries directly affected by the global financial crisis. On the other hand, the high percentage of manufacturing among non-recipients indicates a greater inclination among manufacturing establishments to participate in the survey compared to their non-manufacturing counterparts. It is suspected that respondents’ familiarity with STW strongly influenced survey responses, particularly given the minimal utilization of STW by non-manufacturing establishments before 2008 (Griffin 2010). In sum, the second characteristic leads to an over-representation of the manufacturing sector in the data.

Table 3 illustrates the hiring and separation rates among STW recipients and non-recipients. Upon examination of pre-receipt recipients and non-recipients, it is notable that both groups exhibit similar characteristics, with the separation rate slightly surpassing the hiring rate. However, recipients, in general, demonstrate slightly lower hiring and separation rates compared to non-recipients, implying a lesser employment fluidity for the former. During the receipt period, the separation rate of recipients did not change much from the pre-receipt level. Nevertheless, the hiring rate experiences a notable decline. Subsequently, after the receipt, the separation rate escalates from pre- and during-receipt levels. Although the hiring rate rebounds from the during-receipt phase, it does not fully regain its pre-receipt level. This simple comparison suggests that STW receipt appears to have no discernible effect on reducing the separation rate for recipients, while exacerbating the decline in the hiring rate. In the forthcoming section, I delve into a more nuanced examination of the impact of STW on employment, while accounting for variables such as business conditions and addressing the issue of self-selection into STW.

4 Estimation of base model

4.1 Base model

Our primary interest is the effect of STW on employment adjustments. To assess if STW fulfills the objective of preventing downward employment adjustments, I investigate whether establishments adjust employment differently when they receive STW. Let \({y}_{it}\) denote one of the outcome variables (hiring rate, separation rate, and rate of employment change), and let \({{\varvec{x}}}_{it}\) denote the vector encompassing the percentage change in the overall operation level for establishment \(i\) at time \(t\), along with its squared term. The relationship between changes in employment and the operation level is represented by the following equation:

where \({I}_{it}\) is a dummy variable which takes the value of 1 if the establishment receives STW at time \(t\) and 0 otherwise, \({\eta }_{i}\) is the establishment-specific effect, and \({u}_{it}\) is the error term. \({\eta }_{i}\) is assumed to be time-invariant and potentially correlated with \({{\varvec{x}}}_{it}\).

The effect of STW on employment is collectively captured by the coefficient of STW dummy (\({\beta }_{1}\)) and that of the interaction term between STW dummy and change in operation level (\({{\varvec{\beta}}}_{3}\)). \({\beta }_{1}\) signifies the direct effect of STW on changes in employment, independent of other control variables. This effect may stem from the extension of STW during the survey period, which elevates the subsidy rate in the absence of layoffs. It could also be induced if STW receipt changes the plan for periodic recruitment of new graduates. On the other hand, by subsidizing the cost of adjustments through variations in working time, STW amplifies the relative cost associated with adjustments through hiring and layoffs. Therefore, changes in hiring and separation with respect to changes in operation level are expected to differ based on the take-up of STW. The interaction term serves to capture and quantify this effect.

As previously mentioned, the magnitude of changes in employment in response to operation level and the effect of STW can be influenced by various factors. Even when faced with a similar degree of volatility in business conditions, employers may adjust employment differently due to factors such as variations in management policies, the age distribution of employees, long-term business plans, and other relevant factors.Footnote 11 Unfortunately, most of these establishment-specific characteristics are unobservable. To address this issue, I include \({\eta }_{i}\) and employ a fixed-effect model to eliminate unobserved time-invariant establishment-specific effects.

It is important to recognize that the receipt of STW is not determined randomly. The incentive for establishments to apply for STW varies depending on their specific characteristics, such as the degree of substitutability between work hours and workers, the level of employment rigidity, and other relevant factors. Therefore, the disparity in employment adjustments observed between STW recipients and non-recipients might be attributed to the differing characteristics of these two groups, rather than solely to the causal effect of STW. In other words, the unobservable factors that influence the receipt of STW may be correlated with the outcome variables. To address this issue of self-selection, I treat the receipt of STW as an endogenous variable. The following latent variable model describes the propensity of establishments to receive STW:

where \({I}_{it}^{*}\) is the latent variable of \({I}_{it}\), \({{\varvec{z}}}_{it}\) is a vector of observed characteristics including \({{\varvec{x}}}_{it}\), \({\theta }_{i}\) is the time-invariant establishment-specific effect, and \({v}_{it}\) is the error term. \({{\varvec{z}}}_{it}\) is assumed to be correlated with \({\theta }_{i}\). Following the suggestion of Wooldridge (1995), I assume that \({\theta }_{i}\) depends solely on the time-averaged values of \({{\varvec{z}}}_{it}\) and specify the correlation between \({{\varvec{z}}}_{it}\) and \({\theta }_{i}\) following Mundlak (1978)’s approach. The error terms \({v}_{it}\) and \({u}_{it}\) follow the given distribution:

where

The econometric model presented above is estimated using the two-step estimation method developed by Heckman (1979). The first step is to estimate Eq. (2) as a conventional random-effect probit model. The subsequent step entails estimating Eq. (1) as a fixed-effect linear regression model, with the inclusion of the Heckman correction term derived from the estimation of Eq. (2) in the explanatory variables.

Based upon the estimation results, we can compute average treatment effect (ATE) and ATE on treated (ATET). The ATE of STW computed from the estimates above is

whereas the average treatment effect of STW on the treated is

4.2 Main results

Table 4 presents the key findings of the analysis. Full regression results are relegated to Additional file 1: Appendix 1, and the diagnostic checks performed for this analysis are documented in Additional file 1: Appendix 3. Panel A of Table 4 reports the outcomes of the random-effect probit model for STW take-up, corresponding to Eq. (2). As expected, the coefficients of the operation level and its squared term are both highly significant, indicating a concave negative relationship with the probability of STW take-up. This outcome aligns with the fact that a decline in sales or production is a prerequisite for STW eligibility.

Additionally, we observe a significant positive influence of the average share of STW recipients within an establishment’s industry. Previous studies, based on interviews, revealed that some establishments were concerned that utilizing STW might convey negative signals about their business conditions and financial health to their partners. However, when numerous establishments within the same industry are STW recipients, the negative reputation effect diminishes, resulting in a positive effect on STW take-up. It is crucial to acknowledge that the average share of STW recipients within an industry may also mirror the influence of unobservable industry-specific shocks on labor demand. In this scenario, this variable not only affects STW take-up but also influences the outcome variables. The exogeneity of this variable, along with other excluded variables, is verified in the diagnostic checks outlined in Additional file 1: Appendix 3.Footnote 12

The share of regular employees among the directly hired workers exhibits a significant positive influence on STW take-up.Footnote 13 Regular employees tend to possess establishment-specific skills and are associated with high firing costs. Therefore, establishments with a large share of regular employees are more inclined to utilize alternative employment adjustment measures instead of layoffs. These establishments have a strong incentive to take up STW, as it provides subsidies for such measures.

Panel B of Table 4 presents the findings from fixed-effect regressions, corresponding to Eq. (1), for the hiring rate, separation rate, and rate of net employment change.Footnote 14 Regarding both hiring and separations, the STW dummy variable demonstrates a significant negative impact, with a larger coefficient magnitude observed for hiring. As a result, the coefficient of the rate of employment change is negative, although statistically insignificant. The cross product of the STW dummy and percentage change in operation level is insignificant for the separation rate. However, this variable has a highly significant and positive impact on both the hiring rate and rate of employment change. The results indicate that through its influence on hiring, the use of STW amplifies the effect of operation level changes on employment. Specifically, among non-recipients, a 1% decrease in operation level leads to an average employment reduction of 0.0226%. In contrast, within establishments adopting STW, the magnitude of employment decline is roughly 0.0593 percentage points greater than in non-recipient counterparts. Finally, the covariance between the error terms is positive (negative) and significant for separations (employment change), indicating that unobservable factors contributing to STW take-up tend to increase separations and reduce employment.

Overall, the results of the outcome regression highlight that the impact of STW on employment significantly deviates from the conventional scenario in which STW is supposed to mitigate the negative shock on employment.

Table 5 presents a summary of the estimated ATEs and ATETs for the three outcome variables: hiring rate, separation rate, and rate of employment change. As expected from the results of the fixed-effect regressions, both the ATEs for the hiring rate and separation rate are negative. The absolute value of the ATE is larger for the hiring rate, resulting in a negative point estimate for the rate of net employment change, albeit lacking statistical significance. While the ATETs for the hiring and separation rates are smaller compared to their respective ATEs, their values and statistical significance closely align with those of the ATEs.

Table 5 reveals that STW diminishes recipients’ hiring and separation rates by 3.1424 and 1.4274 percentage points, respectively, culminating in a 1.7150 percentage point reduction in the rate of employment change. A preliminary calculation, employing average establishment size and the count of STW recipient establishments, approximates that in FY 2009, STW constrained hiring by 0.83 million employees and mitigated separation by 0.38 million employees, resulting in an overall reduction of 0.45 million in employment. This equates to approximately 0.7% decline of the employment.

In Additional file 1: Appendix 4, I demonstrate the robustness of these findings, which indicate a negative impact of STW on both hiring and separations, with a stronger effect observed for hiring. These findings remain consistent across alternative model specifications and sample selections.

4.3 Summary and limitations

The estimation results reveal a negative impact of STW on both hiring and separations, with the former effect exerting a greater influence than the latter. There is no compelling evidence supporting a positive effect of STW on employment, as the estimate of the effect on net employment is not statistically significant. These findings are surprising given that the policy objective of STW is to curtail downward employment adjustments.

It is crucial to acknowledge several concerns related to the data and estimation. First, the inherent nature of the Survey and Admin data introduces measurement errors. Furthermore, there is a suspicion that respondents’ familiarity with STW significantly influenced their survey participation, leading to an over-representation of the manufacturing sector in the dataset. Additionally, the lack of precise information on STW eligibility complicates the handling of self-selection biases in STW take-up.

An additional concern arises from the over-representation of regular employees in the sample. Establishments with a high proportion of marginal employees typically exhibit greater employment adjustments during economic downturns and are more likely to be non-recipients as indicated by the results of the selection equation. Therefore, the results may underestimate the true effect of STW. Moreover, the exclusion of establishments that have undergone closure from the sample introduces a survivorship bias, potentially underestimating the effect of STW due to a lack of consideration for its employment retention effect in mitigating business closures.

Furthermore, it is imperative to address the potential presence of remaining selection bias, which may not have been adequately controlled for in the selection equation. Namely, one possible and potentially valid interpretation of the results is that the estimated effects of STW merely reflect the underlying heterogeneity in outcomes, rather than representing the true causal effects of STW, despite the explicit handling of endogenous selection.

Given these concerns, interpreting the results as causal effects of STW on employment becomes challenging. However, the robustness tests detailed in Additional file 1: Appendix 4 affirm the durability of these results—namely, the negative association between STW and hiring, and the absence of compelling evidence for a positive effect of STW on employment—are robust across alternative model specifications and sample selections.

5 Discussion

The key finding is that STW is associated with reduced hiring. A preliminary calculation based on the main results illustrates that, while STW alleviated separations by 0.38 million employees, it concurrently constrained hiring by 0.83 million employees in FY 2009. Some of the alternative estimates even indicate a negative and statistically significant impact on employment change, which suggests that there is no compelling evidence on the positive effect of STW on employment.

So how should we evaluate the STW in Japan based on these findings? A crucial consideration lies in recognizing that the effect of STW varies by employment status. Previous studies, drawing upon both macro and micro data, consistently affirm that the job retention effect of STW is exclusive to permanent employees (e.g., Cahuc and Carcillo 2011; Hijzen and Venn 2011; Lydon et al. 2019). While the main analysis of this study cannot validate this assertion within the context of Japan due to data limitations, two supplementary analyses utilizing data from the Survey reveal that STW exerts a detrimental effect on the recruitment of regular workers. Additionally, it is observed that while STW negatively influences the separation of regular workers, no statistically significant effect is evident regarding the separation of marginal workers (refer to Additional file 1: Appendix 5 for a detailed analysis). The key to interpreting these findings is that STW functions to encourage labor hoarding.

When a firm faces a temporary decline in product demand, it has an incentive to hoard its employees. Although keeping redundant employees incurs costs, labor hoarding avoids the destruction of existing jobs which should be viable again once the downturn is over and thus reducing turnover costs. Therefore, from the perspective of firms, labor hoarding is an efficient strategy when the business decline is expected to be temporary, the existing workers possess significant firm-specific knowledge and skills, layoffs involve high firing costs, and hiring and training expenses are substantial when replacing these workers during an upturn.Footnote 15

STW encourages firms experiencing a business downturn to adjust their workforce by reducing work hours or days instead of resorting to layoffs. By subsidizing a portion of the leave allowance that employers are required to pay for reduced work arrangements, STW lowers the marginal cost of labor hoarding. Consequently, recipient establishments can achieve a higher level of labor hoarding than they would have without STW.Footnote 16,Footnote 17 During the Great Recession, many firms viewed STW as a means to finance the expenses associated with retaining employees. In the Survey, I confirm that a significant number of STW recipients indeed perceived the subsidy as support for labor hoarding, allowing them to maintain sufficient employment levels as the recovery began.Footnote 18 This finding aligns with previous studies by Pissarides (2013) and Hijzen et al. (2015), which observed substantial labor hoarding in Japan during the Great Recession.

Labor hoarding, however, can have some side effects, including a reduction in hiring activities. Given that recipient establishments possess a surplus of labor, they lack the incentive to recruit new workers in anticipation of the recovery phase. Previous investigations of the STW scheme in Germany indicate that the substantial labor hoarding prompted by STW extensions during the Great Recession could impede hiring during the recovery period, leading to jobless growth (Dietz et al. 2010; Möller 2010; Hoffmann and Schneck 2011). My finding of curtailed hiring implies that a similar situation may also arise in Japan.

Two chapters in JILPT (2017), employing identical datasets as this study and investigating changes in the hiring rate at higher frequencies, illustrate a notable reduction in hiring, particularly observed in April during the receipt period.Footnote 19 This observation holds particular significance in the Japanese context, given that many Japanese firms traditionally engage in simultaneous recruitment of new graduates in April, deeming it their primary avenue for hiring regular workers. Consequently, the results imply that recipients tend to curtail the hiring of regular workers by diminishing the planned recruitment of new graduates. If this holds true, this assertion suggests that STW exacerbates the scarring effect, which refers to the enduring negative impact of entering the labor market during a recession on subsequent wages and employment status. Thus, although STW supports job security for existing workers, it transfers adjustment burdens and risks from existing workers to labor market entrants, causing persistent harm.

Furthermore, the selective nature of labor hoarding, favoring certain workers over others, holds particular significance within the Japanese labor market. In Japan, the extent of firm-specific skills possessed by a worker and the costs associated with dismissing them heavily rely on whether they are classified as regular workers within the workplace. Regular workers, typically regarded as core employees, benefit from more training opportunities for firm-specific skills and enjoy greater legal employment protections against dismissals, resulting in high firing costs. Consequently, they are typically prioritized for labor hoarding during economic downturns. Conversely, marginal workers, typically engaged in peripheral roles, serve as a buffer for employment adjustments (Tanaka et al. 2019; Yokoyama et al. 2021). Through subsidizing labor hoarding, STW may reinforce this pattern and widen the gap in job security between the two types of works. As pointed out by Hijzen and Venn (2011), “STW schemes have a tendency to enhance the position of insiders relative to outsiders and thereby further increase the degree of labor market segmentation.”

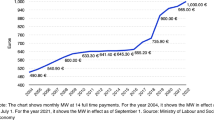

In summary, the main finding on reduced hiring suggests that the substantial level of labor hoarding subsidized by STW exerted a strong negative impact on hiring. By retaining existing regular workers and curtailing hiring, firms shift the burden of adjustments onto external workers and existing workers with limited firm-specific skills or low turnover costs. To accurately evaluate the policy effectiveness of STW, it is crucial to consider these potential adverse consequences of STW on labor market entrants and marginal workers. However, these detrimental effects are challenging to observe, as a significant proportion of labor market entrants unable to secure regular employment and marginal workers experiencing job loss encounter difficulties in re-employment, leading to their withdrawal from the labor force. Figure 2 illustrates that, in contrast to the declining trend in the unemployment rate after its peak in July 2009, the non-labor force population continued to rise until December 2012.

6 Concluding remarks

This study examines the impact of the STW in Japan on employment adjustments during the Great Recession, utilizing establishment-level data from Japan. Despite the data and estimation limitations, the robustness of the findings is confirmed across various model specifications and sample selections. Specifically, it is observed that STW leads to a decrease in both hiring and separations and that there is no compelling evidence on the positive effect of STW on employment. This result diverges significantly from the conventional expectation that STW would alleviate the adverse employment shock.

The curtailed hiring can be interpreted in the context of how STW promotes labor hoarding. By subsidizing the costs associated with retaining excess labor, STW encourages firms to possess redundant employment. The excess labor surplus in STW recipient firms diminishes the incentive to recruit new workers in anticipation of the recovery period. Therefore, STW may reduce the opportunities for new graduates to be hired as regular workers, exacerbating the scarring effect. Moreover, as labor hoarding predominantly applies to regular workers, STW can further widen the disparity in job security between regular and marginal workers. In sum, STW may shift adjustments and risk from existing regular workers onto labor market entrants and marginal workers through subsidizing labor hoarding. To accurately assess the policy effectiveness of STW, it is crucial to consider these adverse effects. My findings have significant implications, particularly for European countries such as France, Italy, and Germany, where STW are extensively employed to mitigate job losses during economic downturns.

This paper leaves several important questions unanswered. Firstly, owing to data limitations, the sample suffers from an over-representation of establishments in the manufacturing sector, as well as an imbalance towards regular workers. These issues not only introduce potential biases in the estimation results but also limit the generalizability of the findings beyond the manufacturing sector and regular workers. Amid the economic downturns resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, the service industry and marginal workers within this sector are particularly affected. Consequently, there is a need for more extensive investigation into the effects of STW on the service industry and marginal workers in future research.

Additionally, my analysis does not provide definitive evidence regarding whether STW subsidize the survival of structurally depressed firms. In the context of the economic setbacks brought by the COVID-19 pandemic, this potential deficiencies of STW may become more pronounced. This is attributed to the fact that STW’s effectiveness significantly depends on the nature of the economic crisis—whether it is primarily driven by a shortfall in demand or by structural impediments.Footnote 20 During a temporary economic downturn resulting from reduced demand, sustaining employment—even if it entails compensating for non-productive hours—is rationale because it avoids the costs associated with layoffs and the subsequent need for rehiring. However, in the context of COVID-19, which is characterized by simultaneous supply and demand shocks and structurally changes in industry dynamics and consumer behaviors, the predictability of business recovery is undermined, leading to uncertainty about the benefits of job retention. Consequently, the efficacy of STW in promoting job retention becomes unclear.

Finally, several experimental exercises conducted to examine the dynamic effects of STW reveal that the negative impact on separation and that on hiring exhibit distinct patterns. Specifically, the former is immediate and short-lived, whereas the latter is characterized by a larger magnitude, more gradual changes, and persistence for over half a year. Other exercises indicate the possibility that the effect of Japanese STW is significant only during the period of the Great Recession’s most pronounced adverse impact. This result suggests that the observation made by Brey and Hertweck (2020), indicating that the effects of STW are most pronounced when GDP growth experiences a sharp negative downturn at the beginning of recessions, may also hold true in the Japanese context. All these findings underscore the importance of investigating the dynamic impacts of STW on employment. Unfortunately, I was unable to capture the dynamic impacts of STW on employment due to the limited time span covered by the available data. A more comprehensive approach could have involved a richer specification of the outcome equation, utilizing lagged policy variables and extending the data coverage over longer periods. Given the complexity of the estimation process and the data limitations, this critical issue remains open for future research.

Availability of data and materials

Two datasets are used in this paper. One is obtained from a survey conducted by JILPT in June and July of 2013, referred to as the “Survey.” Another is the data compiled by the administrative body of the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) in charge of the STW subsidy program, referred to as the “Admin.” The Survey can be accessed through the data archives established by the Japan Institute of Labour Policy and Training, located at https://www.jil.go.jp/kokunai/statistics/archive/datalist.html [in Japanese]. The specific archive identifier for the Survey is no. 115. Access to the Survey can be obtained by submitting an application to the Japan Institute of Labour Policy and Training. The Admin is not available due to the distinct characteristics of administrative data in Japan. Given that administrative data falls outside the purview of the Statistics Law in Japan, its accessibility relies solely on the willingness of the administrative authority (in my case, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare) to grant access to researchers. Unfortunately, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare does not permit public access to the Admin, and I am bound by an obligation not to disclose any portion of the administrative data that I have been authorized to utilize. Consequently, access to the data for replication studies is theoretically possible but requires explicit authorization from the MHLW.

Notes

In common parlance used by labor statistics in Japan, regular (seiki) employees are those working full time with an indefinite length of employment contracts. Marginal (hi-seiki) employees include all employees either working less than full time and/or with a fixed length of employment contracts.

Additional file 1: Appendix 2 offers a comprehensive overview of the institutional background of the STW in Japan.

The overall response rate is 39.7%, with a discernable disparity between recipients at 46.4% and non-recipients at 31.1%; notably, respondents who did note utilize STW exhibited a markedly low response rate. Given the survey’s specific focus on the utilization and impact of STW, it is suspected that the respondents’ familiarity with STW exerted an influence on the response rate, causing selection into the survey. A more thorough explanation of this selection issue will be provided in Sect. 3.2.

Within the Survey, respondents were asked to indicate a numerical value for each fiscal year, reflecting the overall business activity level relative to FY2007, which is set as the reference point at 100. In the questionnaire, JILPT used the term “jigyō katsudō suijun” which I translated as “operation level,” to represent the business activity level of an establishment. JILPT deliberately avoided terms such as “sales” and “production” in the questionnaire, as some establishments are offices without available sales or production figures. The key point is that the respondent is expected to select the most appropriate variable that represents their overall business activity level.

Contrary to the Survey, which is accessible to any researcher upon application to the JILPT, access to the Admin is exclusively granted to researchers authorized by the MHLW. Consequently, while data access for replication studies is feasible in principle, it necessitates explicit approval from the MHLW.

The MHLW exclusively provided the administrative data to the “Study Group on the Utilization and Policy Significance of the Employment Adjustment Subsidy,” convened by the JILPT, with the specific objective of scrutinizing the ramifications of the Japanese STW during the Great Recession. Given the targeted emphasis on the Great Recession, the dataset encompasses information solely spanning from April 2008 to March 2013. Accessibility to the administrative records beyond this delineated period remains restricted, contingent upon authorization from the MHLW.

I also constructed a dummy variable which takes the value of 1 if an establishment received subsidies for at least 3 months in a year, and 0 otherwise. Utilizing this dummy variable, as well as other variables reflecting the extent of STW utilization, such as the subsidy amount received and the duration of temporary leave per employee, as treatment variables does not significantly alter the primary conclusion.

I do not differentiate the effects of subsidies based on their specific uses. In Chapter 7 of JILPT (2017), the effects of subsidies for temporary leave and those for training during regular work hours are estimated separately. The analysis reveals that both the receipt of the subsidy for temporary leave and an increase in the subsidy amount for training may result in a reduction in separations.

Prior to April 2009, the eligibility requirements for workers to enroll in the employment insurance program were: (1) working more than 20 hours per week, and (2) having an employment contract of at least 1 year. Between April 2009 and April 2010, the second requirement was relaxed to six months, and it is further relaxed to 31 days after April 2010.

I thank an anonymous referee for bringing attention to the potential survivorship bias and the bias introduced by the selection into the survey.

For example, an establishment that adheres to customary Japanese employment practices, characterized by significant firing costs, is inclined to minimize dismissals. Similarly, establishments with a substantial proportion of employees approaching retirement age can rely on natural attrition to reduce excessive workforce, which might have necessitated layoffs in other establishments. Conversely, establishments with low substitutability between the number of employees and work hours may maintain a consistent level of dismissals even in the presence of the STW program.

I thank an anonymous referee for highlighting the possibility that this variable could serve as a proxy for changes in labor market tightness, potentially influencing the outcome variables.

The variable’s construction relies on April 2013 data encompassing the number of regular and directly hired employees. As explained in Sect. 5, STW recipients may favor regular workers, introducing potential reverse causality. However, this is the only available data that may capture the magnitude of firing costs for each establishment. Although there is a potential risk of biasing the STW effect, it serves as a firing cost indicator, aiding in self-selection control, given that it remains relatively stable throughout the survey period. Responses to the question regarding employee change in the Survey reveal 50.2% of establishments maintain a relative stable share of regular employees. Notably, excluding this variable does not change the core results.

I also estimated models which incorporate an additional covariate representing macroeconomic shocks, such as the business cycle index and job opening-to-application ratio, in the explanatory variables of the outcome equation. The results align qualitatively with those presented in Table 4.

For a comprehensive overview of the literature pertaining to the emergence and formalization of the labor hoarding concept, refer to Biddle (2014).

I thank an anonymous referee for highlighting the potential scenario wherein firms, expecting the availability of STW, might augment employment in anticipation of the subsidy (labor hoarding). Nonetheless, as stated in Appendix 2, the utilization of STW was notably minimal before the Great Recession. Moreover, it is noteworthy that the relaxation of eligibility criteria for STW occurred for the first time in response to the Great Recession. Consequently, firm behavior prompted by anticipations of the subsidy is deemed unlikely to have occurred.

When surveyed on the hypothetical scenario without STW, 33.5% of recipient establishments responded that “without STW, they would have been compelled to reduce employment further, making it challenging to maintain adequate employment levels during the recovery period.” In another question evaluating STW, 21.1% of the sampled establishments regarded STW as an effective measure for retaining employees for recovery and avoiding costs associated with layoffs and recruitment.

In Chapter 2, Asao conducts a quarterly analysis to compare hiring rates between recipients and non-recipients. The findings indicate that recipients have lower hiring rates during the receipt period, implying the curtailment of hiring during that time. This phenomenon is observed across various industries, including manufacturing, construction, and tertiary sectors. In Chapter 3, Kambayashi examines the data on a monthly basis and identifies that the disparity in hiring rates between recipients and non-recipients primarily manifests in April hiring.

I thank the editor for elucidating the notion that the evaluation of STW is significantly influenced by whether the prevailing economic crisis is predominantly demand-driven or structural in nature.

Abbreviations

- EPL:

-

Employment protection legislation

- JILPT:

-

Japan Institute of Labour Policy and Training.

- MHLW:

-

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare

- STW:

-

Short-time work

References

Balleer, A., Gehrke, B., Lechthaler, W., Merkl, C.: Does short-time work save jobs? A business cycle analysis. Eur. Econ. Rev. 84, 99–122 (2016)

Bellmann, L., Gerner, H., Upward, R.: The response of German establishments to the 2008–2009 economic crisis. OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers 137 (2012)

Biddle, J.E.: Retrospectives: the cyclical behavior of labor productivity and the emergence of the labor hoarding concept. J. Econ. Perspect.perspect. 28(2), 197–212 (2014)

Boeri, T., Bruecker, H.: Short-time work benefits revisited: some lessons from the great recession. Econ. Policy 26(68), 697–765 (2011)

Brey, B., Hertweck, M.S.: The extension of short-time work schemes during the great recession: a story of success? Macroecon. Dyn.. Dyn. 24(2), 360–402 (2020)

Brunner, B., Kuhn, A.: The impact of labor market entry conditions on initial job assignment and wages. J. Popul. Econ.popul. Econ. 27(3), 705–738 (2014)

Cabinet Office Director General for Economic Research: Japanese Economy 2012–2013 [in Japanese] (2012)

Cahuc, P., Carcillo, S.: Is short-time work a good method to keep unemployment down? Nordic Econ. Policy Rev. 1(1), 133–164 (2011)

Cahuc, P., Kramarz, F., Nevoux, S.: The heterogeneous impact of short-time work: from saved jobs to windfall effects. CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP16168 (2021)

Calavrezo, O., Duhautois, R., Walkowiak, E.: Short-time compensation and establishment exit: an empirical analysis with French data. IZA Discussion Paper 4989 (2010)

Chuma, H., Ohashi, I., Nakamura, J., Abe, M., Kambayashi, R.: “Koyō Chōsei Joseikin no Seisaku Kōka ni tsuite (On the policy impact of subsidy for employment adjustments). Japan J Labour Stud 510, 55–70 (2002). ([in Japanese])

Cooper, R., Meyer, M., Schott, I.: The employment and output effects of short-time work in Germany. NBER Working Paper no. 23688 (2017)

Dietz, M., Stops, M., Walwei, U.: Safeguarding Jobs through labour hoarding in Germany. Appl. Econ. Q. 61(Supplement), 125–166 (2010)

Genda, Y., Kurosawa, M.: Transition from school to work in Japan. J. Jpn. Int. Econ. 15(4), 465–488 (2001)

Genda, Y., Kondo, A., Ohta, S.: Long-term effects of a recession at labor market entry in Japan and the United States. J. Human Resour 45(1), 157–196 (2010)

Giroud, X., Mueller, H.M.: Firm leverage, consumer demand, and employment losses during the great recession. Q. J. Econ. 132(1), 271–316 (2017)

Giupponi, G., Landais, C.: Subsidizing labour hoarding in recessions: the employment and welfare effects of short-time work. Rev. Econ. Stud. 90(4), 1963–2005 (2022)

Griffin, N.N.: Labor adjustment, productivity and output volatility: an evaluation of Japan’s employment adjustment subsidy. J. Jpn. Int Econ. 24(1), 28–49 (2010)

Hamaguchi, K.: The employment adjustment subsidy and new assistance for temporary leave. Japan Labor Issues 4(27), 2–8 (2020)

Hamaguchi, K.: Koyō Joseikin no Hanseiki (The half century of employment adjustment subsidy). Q. Labor Law 243 (2013) [in Japanese]

Heckman, J.: Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica 47, 153–161 (1979)

Hijzen, A., Martin, S.: The role of short-time work schemes during the global financial crisis and early recovery: a cross-country analysis. IZA J. Labor Policy 2(1), 1–31 (2013)

Hijzen, A., Kambayashi, R., Teruyama, H., Genda, Y.: The Japanese labour market during the global financial crisis and the role of non-standard work: a micro perspective. J. Jpn. Int. Econ. 38, 260–281 (2015)

Hijzen, A., Venn, D.: The role of short-time work schemes during the 2008–09 recession. OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers no. 115 (2011)

Hoffmann, M., Schneck, S.: Short-time work in German firms. Appl. Econ. Q. 57(4), 233–254 (2011)

Japan Institute of Labour Policy and Training: Koyō Chōsei Joseikin no Seisaku Kōka ni Kansuru Kenkyū (A study on the policy impact of employment adjustment subsidy) [in Japanese]. JILPT Research Report No. 187. http://www.jil.go.jp/institute/reports/2016/0187.html (2017)

Kahn, L.: The long-term labor market consequences of graduating from college in a bad economy. Labour Econ. 17(2), 303–316 (2010)

Kambayashi, R.: Mismatch and labor market institution: the role of short-time work subsidy during the recent crisis (Rōdō Shijō Seido to Misumacchi -Koyō Chōsei Joseikin wo Rei ni) [in Japanese]. Jpn. J. Labour Stud. (Nihon Rodo Kenkyu Zasshi) 626, 34–49 (2012)

Kondo, A.: Does the first job really matter? State dependency in employment status in Japan. J. Jpn. Int. Econ. 21(3), 379–402 (2007)

Kopp, D., Siegenthaler, M.: Short-time work and unemployment in and after the great recession. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 19(4), 2283–2321 (2021)

Kruppe, T., Scholz, T.: Labour hoarding in Germany: employment effects of short-time work during the crises. IAB-Discussion Paper No. 17 (2014)

Kwon, I., Milgrom, E.M., Hwang, S.: Cohort effects in promotions and wages evidence from Sweden and the United States. J. Human Resour. 45(3), 772–808 (2010)

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare: White Paper on the Labor Economy. [in Japanese] (2021)

Lydon, R., Mathä, T.Y., Millard, S.: Short-time work in the great recession: firm-level evidence from 20 EU countries. IZA J. Labor Policy 8(1), 1–29 (2019)

Möller, J.: The German labor market response in the world recession - de-mystifying a miracle. J. Labour Market Res. (zeitschrift Für Arbeitsmarktforschung) 42(4), 325–336 (2010)

Mundlak, Y.: On the pooling of time-series and cross-sectional data. Econometrica 56, 69–86 (1978)

Oreopoulos, P., von Wachter, T., Heisz, A.: The permanent and transitory effects of graduating in a recession: an analysis of earnings and job mobility using matched employer-employee data. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 4(1), 1–29 (2012)

Pissarides, C.A.: Unemployment in the great recession. Economica 80, 385–403 (2013)

Puhani, P.: The Heckman correction for sample selection and its critique. J. Econ. Surv. 14(1), 53–68 (2000)

Steinberg, C., Nakane, M.: To fire or to hoard? Explaining Japan’s labor market response in the Great Recession. International Monetary Fund Working Paper 11/15 (2011)

Tanaka, A., Ito, B., Wakasugi, R.: How do exporters respond to exogenous shocks: evidence from Japanese firm-level data. Jpn. World Econ.. World Econ. 51, 1–12 (2019)

Van Audenrode, M.A.: Short-time compensation, job security, and employment contracts: evidence from selected OECD countries. J. Polit. Econ. 102(1), 76–102 (1994)

Wooldridge, J.: Selection corrections for panel data models under conditional mean assumptions. J. Econ. 68, 115–132 (1995)

Yokoyama, I., Higa, K., Kawaguchi, D.: Employment adjustments of regular and non-regular workers to exogenous shocks: evidence from exchange-rate fluctuation. Ind. Labor Relat. Rev.relat. Rev. 74(2), 470–510 (2021)

Acknowledgements

This paper is based upon a chapter that I and Kenn Ariga (Emeritus Professor, Institute of Economic Research, Kyoto University) coauthored in a research report (JILPT, 2017) by the committee organized by the Japan Institute of Labour Policy and Training to investigate the policy effects of Employment Adjustment Subsidy. I am grateful to him for affording me the opportunity to expand upon the foundation laid by our analysis and finalize this paper as a sole-authored manuscript. I am particularly grateful to two anonymous referees and the editor Joachim Möller for their detailed comments and suggestions. I also wish to thank all the committee members as well as the Japan Institute of Labour Policy and Training and the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (Japan) for the provision of the administrative records of the subsidy, without which this research could not have been done. Remaining errors are all my own.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Not applicable.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Appendices 1-5.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kuo, CW. Short-time work, labor hoarding, and curtailed hiring: establishment-level evidence from Japan. J Labour Market Res 58, 7 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12651-024-00365-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12651-024-00365-y