Abstract

Background

In Germany and the EU, most headwaters are still far from reaching a good chemical and ecological status as it is required by the European Water Framework Directive (WFD), until 2027 the latest. Particularly, in densely populated areas, impacts from municipal and industrial wastewater discharges or diffuse agricultural emissions are still a matter of concern. This also applies to the Nidda River which is considered to be in a moderate to rather poor condition. In our study, we investigated short-term and long-term consequences of anthropogenic pollution on fish health via one monitoring with caged fish (CF) and two field sampling campaigns (FF). In the CF monitoring, rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) were caged for seven weeks at four selected sites along the Nidda, whereas in the FF monitoring approach, feral fish, including brown trout (Salmo trutta f. fario), European chub (Leuciscus cephalus) and stone loach (Barbatula barbatula) were caught in June and September 2016.

Results

Histopathological analyses of liver and gills were conducted, accompanied by measurements of hepatic 7-ethoxyresorufin-O-deethylase (EROD) activity to assess the cytochrome P450 (CYP1A1) function, and genotoxicity via the micronucleus assay. Caged as well as field-captured fish exhibited impaired health conditions showing lesions particularly in the liver, and a presumably overwhelmed CYP1A1 system, whereas genotoxicity was not induced. The variation between sampling sites and seasons was rather low, but two trends were recognisable: (a) liver condition was poorest around spawning season and (b) tissue integrity and EROD activity were most affected downstream of industrial dischargers. Furthermore, effects were species dependent: the generally highly sensitive S. trutta f. fario proved to be impacted most, whereas L. cephalus with its pelagic lifestyle was affected less than the benthic B. barbatula, indicating a relevant contamination of sediments.

Conclusion

Our results confirm the impaired ecological state of the Nidda and emphasise that a sustainable improvement of aquatic ecosystem health needs to include both water quality and sediment contamination to approach the ambitious WFD goal.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

According to the European Water Framework Directive (WFD), European water bodies have been supposed to meet the criteria for at least a good chemical and ecological status until 2015 [103]. With only 7.9% of surface waters in Germany reaching a ‘good’ and considerably less than 1% reaching a ‘very good’ ecological state, the achieved results fell short of the ambitious 2015 goal [15]. Thus, the deadline for a successful implementation of the WFD has been prolonged until 2027 and the efforts to accomplish the objectives have been intensified.

In that context, the project network NiddaMan aimed at comprehensively investigating the ecosystem health of a highly anthropogenically influenced river system in Central Hesse, Germany, and at identifying potential key factors of pollution to support and advise authorities in their effort to improve the ecological state. As NiddaMan abbreviates ‘Nidda management’ the focus was placed on the catchment of the river Nidda, a tributary of the Main River, representing a characteristic European river system passing the second largest urban agglomeration in Germany, Rhein-Main, with a total population of 6 million. Point sources, particularly wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) for municipal and industrial wastewater, as well as diffuse emissions from intense agricultural land use are regarded as main contributors to the prevailing ecological situation. According to the WFD status update from 2015, the Nidda was in a moderate to a rather poor ecological state [15]. Hydromorphological, physicochemical and biological quality components are the three major pillars the ecological status assessment is based on [15]. Although hydromorphological and (physico-)chemical parameters provide considerable insight to structure and water quality of aquatic systems, present information remains insufficient to conclude on the potential biological responses. Chemical analytics mainly focus on priority substances and thus cover only a tiny part of the highly diverse spectrum of compounds introduced—it is estimated that up to 90% of the detected environmental toxicity is caused by unknown chemicals [42]. Additionally, sole detection and quantification of compounds cannot account for the effects of chemical interactions and the subsequent impact these cocktails exert on organisms. In particular, substance interactions within mixtures frequently lead to additive or synergistic effects, despite concentrations of present single compounds may, eventually, be considerably lower as previously identified as harmful [42, 67, 118]. Combined with various natural stressors (e.g. temperature, food availability, predation, reproduction and parasites) which often act synergistically [47] and potentially enhance adverse effects by lowering organismal resilience, mixture toxicity cannot be extrapolated from (physico-)chemical parameters, but have to be assessed by measuring biological responses in exposed organisms, e.g. by using biomarkers [3, 6, 20, 21, 90, 110, 120].

Besides phytoplankton, algae, phytobenthos and macroinvertebrates, fish are among key factors within the biological quality components and used as indicators for ecosystem health [15]. Fish represent the highest trophic level in the aquatic ecosystem and are in direct contact with the surrounding medium; thus, their physical condition gives a valuable indication of the contamination level of the investigated water body. Numerous studies have shown the influence of water quality and pollution on the physical condition of fish living in the wild [63, 64, 105, 109, 113, 124].

In this study, we particularly focus on fish health in the Nidda by investigating subacute and chronic effects of pollution, including municipal and industrial discharges in an otherwise intensely used agricultural area. To cover a broad range of potential health issues, different endpoints were investigated. Histopathological assessments of liver and gill were conducted, as the liver is responsible for detoxification of xenobiotics through various enzymes [61, 70, 85], whereas the gills are in direct contact to the surrounding medium and particularly involved in the exchange of substances between the organism and its environment [68]. Therefore, both organs are particularly susceptible to influences of harmful compounds, which are regularly reflected in tissue integrity [7, 87, 124]. Additionally, we quantified the 7-ethoxyresorufin-O-deethylase (EROD) activity in the liver which is linked to the cytochrome P450 1A (CYP1A) level affected by certain groups of xenobiotics, including dioxin-like substances, planar polyhalogenated/polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PHHs/PAHs) and coplanar polycyclic biphenyls (PCBs) and other classes of compounds inducing the primary detoxification processes [17, 19, 25, 91, 119]. Alteration in EROD activity is considered to be a highly sensitive biochemical marker of xenobiotic exposure in fish [28, 64, 120, 121, 125]. To assess genotoxic potentials, the widely used micronucleus assay [2] was applied on fish blood samples [105, 113, 125].

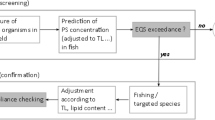

Based on the biomarker triad (histopathology, EROD activity and micronucleus assay) and the determination of the total lipid content as an indicator of available energy storage, we investigated the health of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) reflecting potential subchronic effects in a seven-week caging approach (CF). Furthermore, we studied the health of field-captured feral fish (CF) (Salmo trutta f. fario, Leuciscus cephalus and Barbatula barbatula) mirroring long-term exposure, and thus, chronic effects at four sites along the Nidda River in two monitoring campaigns in spring and autumn 2016.

Finally, in order to narrow down the potential causes of the observed biological responses, water and sediment samples from the respective sampling sites were analysed, and the bioaccumulation of defined substances in the muscle tissue of the fish was determined. The focus was placed on municipal wastewater-borne as well as pesticide pollution from agricultural usage and some industrial chemicals for the water analyses, whereas sediments and fish muscle tissue were analysed for metal(loid)s and rather lipophilic substances with a high bioaccumulation potential, including PCBs.

Material and methods

Sampling location

The Nidda River is located in Central Hesse, Germany. It has its source in a low mountain range of volcanic origin (Vogelsberg) in eastern Hesse and enters the Main near Frankfurt. With a catchment of 1619 km2, the Nidda river system belongs to the most important surface waters in Hesse [95]. Along its course of 89.7 km, the Nidda passes a densely populated area characterised by anthropogenic influences, like intense agricultural land use and the effluents of point sources, particularly wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) discharging both municipal and industrial wastewater [95]. The Nidda undergoes an increasing urbanisation from source to mouth. The specified attributes characterise the Nidda as a typical anthropogenically influenced European river system.

Sampling sites

Fish health was assessed at four sites (N1, N2, N3 and N6; see Fig. 1; Table 1) along the headwater and middle reaches of the Nidda.

The first sampling site N1 was within the upper trout zone [45] and was located 4.5 km downstream the Nidda River dam. As the most upstream site, N1 was selected to supposedly act as an in-river control. The area surrounding N1 was rather rural and mainly characterised by grassland and agriculture. N2 was established about 0.7 km downstream of industrial dischargers and was located within the grayling zone [45]. The distance between N1 and N2 amounted to 3.6 km. Downstream N2, the grayling zone transitioned into the barbel zone [45] and the agricultural land use increased. Upstream N3, a class-IV WWTP accounting for 35,000 people equivalents (pe) discharged into the Nidda. N3 was established 7 km downstream N2. The last sampling site N6 was located within the barbel zone [45] and about 22.3 km downstream N3. Along its course from N3 to N6, one class-IV WWTP with 30,000 pe, two class-III WWTPs with 7500 and 7000 pe, respectively, as well as the effluxes of the tributaries Horloff and Usa/Wetter discharged into the Nidda. N6 itself was characterised by intense agricultural land use and increasing urbanisation.

Caging of fish (CF)

To account for subchronic effects, hatchery-bred juvenile rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) were exposed in the Nidda River at sites N1, N2, N3 and N6. Fish were obtained from a local fish hatchery (Fischzucht Rameil, Fritzlar, Germany). The cages were made of perforated stainless steel, 0.6 × 1 × 0.5 m in size, and equipped with two floaters each. One cage per site was placed in the Nidda and secured with chains at the riverbank. Each cage contained twenty rainbow trout individuals of about 20 cm in size. The exposure duration spanned seven consecutive weeks and lasted from mid-February to the beginning of April 2016. During that time, rainbow trout fed on invertebrates passively drifted into the cages by river water. Nevertheless, to exclude eventual starving effects, the caged fishes were additionally provided with food pellets from the hatchery and checked for mortality every second day.

Alongside the field exposure, two hatchery controls (HC1, HC2) were run. For HC1, twenty individuals held in breeding tanks were sampled at the hatchery prior to the field exposure. For HC2, twenty rainbow trout individuals were kept at the hatchery separately from the other fish in the respective breeding tanks parallel to the caging and sampled at the same time as the individuals from the field exposure.

Monitoring of field-captured fish (FF)

To investigate potential chronic effects, three different species of feral fish, brown trout (Salmo trutta f. fario), European chub (Leuciscus cephalus) and stone loach (Barbatula barbatula), were caught at the respective sampling sites at the Nidda in spring (June) and autumn (September) 2016 by electrofishing. At each site, two species were sampled representing different ecological niches: on one hand, a species inhabiting mainly the water column with restricted migration tendencies that is able to evade the impact of point sources to some extent (brown trout/chub) referred to as pelagic, and on the other hand, a rather sediment-bound stationary species that is exposed to pollution in its entirety (stone loach) referred to as benthic. Due to the different habitat types (for fish zones see Table 1) along the course of the Nidda, it was not possible to sample identical species at all sites (Table 2). Furthermore, at site N2, brown trout replaced chub as sampling species in autumn and, at N3, sampling success was restricted to stone loach only.

Dissection of fish and preparation of samples

Fish were killed with an overdose of 1 g/L tricaine methane sulphonate (Tricaine Pharmaq 1000 mg/g, PHARMAQ Ltd., Sandleheath, UK) solved in water and buffered to pH 7 with NaHCO3, followed by a spinal severance. Size and weight were immediately recorded prior to further dissection on site.

Total lipid content analysis

For the analysis of the total lipid content, the fish fillet was used. The fillet was separated from the fishbone in the field, directly frozen on dry ice and stored at − 20 °C until further processing. The analysis was conducted according to Smedes [99] and has also been used by Wick et al. [123] for determining the lipid content of bream liver (for further details see Additional file 2: “1. Procedure of lipid content analysis”).

Histopathology

Liver and gill samples were dissected on site and immediately fixed in 2% glutardialdehyde (GA) diluted with 0.1 M cacodylate (Caco) buffer (pH 7.6), before they were adequately stored until their further processing in the laboratory (for details see Additional file 2: “2. Preparation and staining of histopathological samples”).

Tissue sections were assessed qualitatively and semi-quantitatively under an optical microscope (Axioskop 2, Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH, Jena, Germany). Semi-quantification of the results was achieved by applying the technique of Schwaiger et al. [96] and Triebskorn et al. [108] using five assessment categories, including control status (I), reaction (III) and destruction (V), complemented with intermediate categories (II and IV).

EROD activity

To assess the hepatic CYP1A1 EROD activity, liver tissue was frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at − 80 °C until further processing (for details see Additional file 2: “3. Processing of liver samples for the EROD assay”).

The assay, based on the transformation of the added substrate ethoxyresorufin into the fluorescent resorufin, was conducted in 96-well plates using a fluorimeter (FLx800, BioTek Instruments®, Inc., Bad Friedrichshall, Germany) at wavelengths of 530 nm for excitation and 585 nm for emission. In combination with the total amount of protein determined according to Bradford [22], the EROD activity per mg tissue was calculated with the software Gen 5 (BioTek Instruments®, Inc., Bad Friedrichshall, Germany).

Micronucleus assay

For the micronucleus assay, blood was taken from the caudal vein directly before dissection of fish (for details see Additional file 2: “4. Micronucleus assay procedure”).

Per individual, 2000 erythrocytes were examined under an optical microscope (Axioskop 2, Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH, Jena, Germany), and the amount of occurring micronuclei and binuclei was recorded.

Physicochemical parameters

At each site (including the hatchery) and time point, the physiochemical water parameters were recorded. Water temperature, oxygen content, pH and conductivity were measured with respective electrodes (Hach® HQ40d multi, pHC201, LDO101, CDC401, Hach Company/Hach Lange GmbH, Germany), water hardness (MColortest™, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) and sulphate (visocolor®ECO, Macherey–Nagel GmbH & Co. KG, Düren, Germany) were titrimetrically determined and the concentrations of nitrate, nitrite, ammonium, phosphate and chloride were photometrically measured (Photometer Nanocolor® PF-12, Macherey–Nagel GmbH & Co. KG, Düren, Germany).

Chemical analytics

Water and sediment samples for analysis of chemical pollutants were collected as grab samples between September 2015 and July 2016 (Additional file 2: Tables S4, S5). Water samples were analysed for polar emerging pollutants (N1: n = 35, N2: n = 30, N3: n = 31, N6: n = 34). Sediment samples were analysed for metal(loid)s (N1: n = 8, N2: n = 7, N3: n = 5, N6: n = 7) as well as polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and other semi-volatile halogenated compounds (SVOC) (N1: n = 6, N2: n = 4, N3: n = 3, N6: n = 6).

Fish muscle tissue was also analysed for metal(loid)s, PAHs, PCBs and other SVOC but even an extended set of 45 individual pollutants were measured and reported (see Additional file 2: Table S6). For example, the musk fragrance tonalide was included as a bioaccumulating indicator for the influence municipal wastewater [27, 39]. To consider the limited amount of muscle tissue of each individuum as well as the limited analysis capacity, concentrations were determined for each sampling point in pooled samples of eight individuals of the same species.

Analysis of polar emerging pollutants in water

In total 38 emerging pollutants (13 biocides, 20 pharmaceuticals, 3 artificial sweeteners 1 corrosion and 1 specific industrial compound) were analysed by liquid chromatography (Agilent 1260 infinity series) coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (Sciex Triple Quad 6500 +) (LC–MS/MS) according to a method published by Hermes et al. [43] (for a detailed description, see Additional file 2: “5. Analysing procedure of polar pollutants in water”). The compounds were selected based on their frequency of detection in literature and persistence in urban water cycles. They comprise already regulated priority pollutants (isoproturone, terbutryn and diuron) and river basin specific pollutants (triclosan, mecoprop, terbuthylazine, metazachlor, metolachlor, imidacloprid, carbendazim and propiconazole) as well as compounds of the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Watch List under the Water Framework Directive (diclofenac, sulfamethoxazole, trimethoprim, venlafaxine and O-desmethylvenlafaxine and fluconazole). Moreover, compounds, such as the antiepileptic carbamazepine and the artificial sweetener sucralose, were selected as they are conservative tracers of municipal wastewater [92].

Analysis of metal(loid)s in sediments and fish

The nitric acid soluble fraction of metals (Cd, Cr, Cu, Ni, Pb, Zn and Hg) and the metalloid arsenic were extracted from 1 g of the 0.63 µm fraction of freeze-dried and ground sediment samples or 0.25 g of freeze-dried pooled fish fillet samples by microwave digestion according to DIN EN 16173. All these elements except for mercury were analysed in the extracts using an ICP-OES (Perkin Elmer Optima 8300, Shelton, USA). Mercury was analysed according to die DIN EN ISO 17852:2008-04 using atomic fluorescence spectrometry (Analytik Jena Mercur, Jena, Germany).

Analysis of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and other semi-volatile halogenated compounds (SVOC) in sediments and fish

SVOC and PAHs were analysed according to the slightly modified standard protocols prEN 16167:2010 and prEN 16181:2010, respectively. Briefly, 10 g of freeze-dried, ground and sieved (< 2000 µm) sediment samples or 0.5 g of freeze-dried pooled fish fillet samples was extracted by pressurised liquid extraction (PLE) using an ASE-200 (Dionex, Idstein, Germany). The extraction of the samples was done in two cycles, each with 30 mL of a mixture of iso-hexane, acetone and n-heptane (62:33:5; v/v/v). Subsequently, a mixture with surrogate standards was added containing 29 13C-labelled chlorinated compounds (e.g. PCBs, HCHs, DDXs) and 16 deuterated PAHs. Sample extracts were concentrated to 5 mL using a Synchore evaporator (BÜCHI, Konstanz, Germany) at 40 °C. The extracts were subjected to a sandwich column clean-up with deactivated aluminium oxide (Al2O3) and freshly activated copper powder for sulphur removal. Afterwards, a GPC clean-up was accomplished and the final sample volume was reduced to 0.5 mL before GC–MS/MS analysis (Agilent/Chromtech Evolution, Idstein Germany).

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses were conducted with JMP® 13.0.0 (SAS Institute Inc.) Data were checked for normal distribution and homogeneity of variances. Histopathological data were analysed with a pairwise likelihood-ratio χ2 test. The α-levels were corrected for multiple testing according to the Bonferroni-Holm method [46]. EROD activity is usually dependent on sex and age. Regarding the CF monitoring, purchased O. mykiss were all females of the same age; thus, a differentiation of the data set was not necessary. In case of fish from the FF monitoring, the sex was determined and the individual size was used as proxy for age. In a two-way ANOVA, the influence of both factors on EROD activity were investigated and shown insignificant (p > 0.05). Therefore, results for EROD activity were pooled to gain a larger data set. As the data sets for EROD activity were not normally distributed, a transformation with 3√(L. cephalus and B. barbatula) and 4√(S. trutta f. fario) was necessary to allow ANOVA analysis combined with a Tukey–Kramer HSD post hoc test. The micronuclei data were assessed with a likelihood-ratio χ2 test, followed by pairwise Fisher’s exact tests and a correction for multiple testing according to Bonferroni-Holm [46]. In case of the CF monitoring, HC2 was used as reference control for the statistics, because those individuals were sampled at the same time point as the individuals in the field. Data from the FF monitoring was compared between sampling sites and within sampling sites between seasons whenever sufficient data were available.

Results

Mortality and morphological characteristics

The mortality of caged Oncorhynchus mykiss was consistently low at sampling sites N1, N2 and N3 with three (at N1), or two (at both N2 and N3) dead individuals. At site N1, additionally one individual escaped from the cage. At N6, mortality was higher and reached 30.0%.

At the end of the experiment, caged fish were in the same mean weight and size range as fish from HC1 that were sampled in parallel to the start of the exposure, whereas individuals from HC2, fed at the hatchery and sampled at the same time point as the Nidda-exposed fish, increased in mean size and weight (Table 3). Mean weight of O. mykiss was increasing slightly from N1 to N3 and decreased at N6.

In case of field-captured fish, size and weight varied more between seasons than between sampling sites with exception of B. barbatula: individuals from N1 weighed considerably more than individuals from the other sites. Weight of S. trutta f. fario and L. cephalus individuals was higher in autumn than in spring. Counter-intuitively, lipid content was higher in individuals with lower weight, except in S. trutta f. fario and O. mykiss controls (HC2) and, in case of B. barbatula, highly dependent on the season.

Histopathology

The histopathological analysis revealed, in general, a better health condition of caged fish compared to field-captured fish (Figs. 2, 3). Oncorhynchus mykiss that were either kept in the hatchery or were exposed to the river water for seven weeks showed particularly less karyolysis, necrosis and inflammations in the liver tissue, as well as less aneurysms and necrosis in the gills than feral S. trutta f. fario, L. cephalus and B. barbatula caught in the Nidda (for the proportions of the specific effects see Additional file 2: Tables S1, S2). Comparing the different time points within the FF monitoring, there was a tendency to severer effects in June compared to September in B. barbatula, and vice versa in S. trutta f. fario and L. cephalus. This tendency was most pronounced in the liver.

Semi-quantitative assessment of liver histopathology; a O. mykiss (CF monitoring); b S. trutta f. fario (FF monitoring); c L. cephalus (FF monitoring); d B. barbatula (FF monitoring); significant differences between sampling sites or seasons are either marked with different letters or by asterisks; liver sections stained with HE; e control; f reaction status; g destruction

Semi-quantitative assessment of gill histopathology; a O. mykiss (CF monitoring); b S. trutta f. fario (FF monitoring); c L. cephalus (FF monitoring); d B. barbatula (FF monitoring); significant differences between sampling sites are marked with asterisks; gill sections stained with HE; e control; f reaction status; g destruction

Liver

The liver of caged O. mykiss was in a significantly worse condition than liver of the hatchery controls (Fig. 2a; likelihood-ratio χ2, p < 0.01*) and exhibited dilated capillaries, dilated bile canaliculi and intercellular spaces (Additional file 2: Table S1). Liver tissue from individuals exposed at site N1 was mainly in a slightly better condition than livers of fish taken at N3 and N6, and significantly less affected than liver tissue from fish kept at N2 (likelihood-ratio χ2, p < 0.0029*). Livers from fish from all exposure sites and HC2 showed a lower glycogen content that was increasingly reduced in downstream direction. Particularly in N6 individuals, a depletion in glycogen was noticed in every examined sample. Generally, severer effects, including inflammations, haemorrhages, karyolysis and necrosis, as well as the metabolic response of hyperplasia of hepatocytes only occurred in a rather small proportion of samples (< 25%).

The livers of feral S. trutta f. fario at sampling N1 and N2 showed considerable adverse effects. Tissue samples collected from N1 individuals in June as well as in September were in a reaction status (category III) or in between reaction and destruction (category IV), whereas samples from N2 (September) were mainly allocated to category IV or even V (destruction) (Fig. 2b) and characterised by severe haemorrhages, but were not statistically different from the N1 September samples (likelihood-ratio χ2, p = 0.028, p > α). S. trutta f. fario livers were more affected in September than in June, but a comparison between seasons were only possible for N1, as no S. trutta f. fario individuals could be sampled at N2 in spring. Individuals from both sampling sites and time points showed a considerably low glycogen content in the liver.

L. cephalus livers from N6-exposed individuals were mainly in between control status and the reaction status (category III), whereas > 20% of livers from N2 individuals were allocated to the destruction status (Fig. 2c). A high percentage of liver samples from both sampling sites and time points showed dilated capillaries and inflammations (Additional file 2: Table S1). The glycogen content was low, particularly in individuals caught at N6 in autumn. Those individuals were in a worse condition than individuals caught in spring. But neither differences between sampling sites nor between time points were statistically significant (likelihood-ratio χ2, p > 0.05). At N2 in September, as well as at N3, generally, no chub was caught.

In case of B. barbatula liver samples, the health classification spanned across categories from II to V (Fig. 2d). In this respect, individuals caught in spring, as well as those originating from sampling site N2 were, by tendency, in a worse condition than their conspecifics caught in autumn or at the other sites. However, only the difference between individuals at N3 in spring and autumn was proven statistically significant (likelihood-ratio χ2, p = 0.008*). A reduced glycogen content compared to the controls was present in livers from all sampling sites and seasons, but predominantly in June (Additional file 2: Table S1).

Summarising, livers of feral fish were affected to a higher extent than livers of the caged O. mykiss. The severest cellular responses were detected in livers of S. trutta f. fario individuals, particularly at sampling site N2. Generally, N2 was the sampling site at which fish showed the most effects independent of the species or season.

Gills

The gills of exposed O. mykiss were in a slightly but statistically insignificant worse condition compared to the hatchery control (likelihood-ratio χ2, p = 0.1521), and mainly classified as to be in a reaction state (category III) (Fig. 3a). The cellular reactions included hypertrophy of chloride cells, a reduced number of mucocytes, the fusion of secondary lamellae and epithelial lifting. More severe effects, including inflammations, aneurysms and necrosis, occurred very scarcely.

The gills of S. trutta f. fario sampled at sites N1 and N2 showed similar results for both sampling sites in September with gills mainly in a status of reaction (Fig. 3b). Gills from individuals caught in June at N1 were still in an intermediate state between control condition and reaction (category II) in 70% of the cases, but statistically insignificantly different to the September samples (likelihood-ratio χ2, p = 0.054). Cellular responses included hypertrophy and hyperplasia of pavement and chloride cells, as well as a considerably less mucocytes particularly in gills from individuals sampled in September (Additional file 2: Table S2).

In case of L. cephalus, gills of individuals originating from sampling site N2 were in a significantly worse condition (likelihood-ratio χ2, p = 0.0116*) with 50% of samples classified as to be in the intermediate state between reaction and destruction (category IV), compared to those from sampling site N6 (Fig. 3c). Almost all gills showed hyperplasia of pavement cells and hypertrophy of mucocytes, whereas epithelial lifting and necrosis mainly occurred in individuals caught at N2 (Additional file 2: Table S2).

The condition of gill tissue of B. barbatula did not differ neither between sampling sites (likelihood-ratio χ2, p = 0.0902 (June)/p = 0.4123 (September) nor seasons (likelihood-ratio χ2, p > α). All samples were categorised between categories II and IV, except for gills from individuals caught at N6 in spring, which were in a slightly worse condition (Fig. 3d). The main effects observed in individuals from all sampling sites at both seasons were hyperplasia of pavement cells, hypertrophy of mucocytes and epithelial lifting (Additional file 2: Table S2). Additionally, necrosis occurred in 20–30% of all gill samples independently of sampling site or season.

Altogether, the gills were generally in a better condition than the livers. The gills of caged O. mykiss were less affected than the gills of feral fish, but the difference between caged and feral fish was less pronounced than it was observed in liver tissue. Furthermore, little variation between sites was detected and no sampling site was particularly salient.

EROD activity

In the caging experiment, the EROD activity was highest in the control fish (HC2). In the field, individuals from sampling sites N1, N3 and N6 showed a slightly but insignificant reduction in their EROD activity (ANOVA, Tukey Kramer HSD, p > 0.05), whereas in O. mykiss from N2 the induction was considerably low (ANOVA, Tukey Kramer HSD, p < 0.05*) (Table 4).

Considering the field-captured fish, only in S. trutta f. fario individuals caught at sampling site N1, EROD activity was significantly higher in June than in September (ANOVA, Tukey Kramer HSD, p = 0.0299*). No differences in EROD activity were detected in L. cephalus and B. barbatula individuals neither between sampling sites nor between seasons (ANOVA, Tukey Kramer HSD, p > 0.05).

Micronucleus assay

The number of micronuclei and binuclei was generally low, in both caged and feral fish (Table 4). No differences in genotoxicity were found in O. mykiss from the CF monitoring experiments, neither considering micronuclei (likelihood-ratio χ2, p = 0.8928) nor binuclei (likelihood-ratio χ2, p = 0.0199*; Fisher’s exact p > 0.05).

In S. trutta f. fario significantly elevated levels of micronuclei were found in fish from N1 caught in June compared to individuals from September (likelihood-ratio χ2, p = 0.0034**; Fisher’s exact p = 0.0238*). Furthermore, an increased number of binuclei were detected in individuals from N2 caught in September 2016 compared to individuals caught at N1 at the same time (likelihood-ratio χ2, p = 0.0001***; Fisher’s exact p = 0.0025*). Neither levels of micronuclei nor binuclei were significantly different in L. cephalus (likelihood-ratio χ2, p = 0.6332 (micronuclei)/likelihood-ratio χ2, p = 0.2936 (binuclei) or B. barbatula [likelihood-ratio χ2, p = 0.0307*; Fisher’s exact, p > 0.05 (micronuclei)/likelihood-ratio χ2, p = 0.4577 (binuclei)] at any occasion.

In summary, genotoxicity was not an issue in fish from the investigated Nidda River sampling sites.

Finally, an overview of all biological responses in potential dependence of site or season is given in Table 5.

Physicochemical parameters

Most parameters were in the expected range (Additional file 2: Table S3), including rising temperatures and, in parallel, declining oxygen contents during the course of the year. The pH varied between 7 and 7.8 peaking in September at all sampling sites. Several parameters, including nitrite, orthophosphate as well as chloride concentrations, and thus conductivity, were continuously increasing from N1 to N6. In particular, chloride concentrations and conductivity levels were extremely high at N6 in September, conceivably caused by inflow of water from the Usa/Wetter river system that carries the discharge from mineral spas. Nitrate levels were high in February and September, particularly at sites N2 and N6 exceeding the threshold of a good chemical status of 11.3 mg/L according to the European Nitrates Directive 91/676/EEC [101]. Elevated levels of ammonium were measured mainly at N3 in April and June. Whereas the ammonium levels were still within the range of a good chemical status according to the German surface waters regulation OGewV [16], the nitrite levels recorded at N3 (June, September) and N6 (June) were not. Results showed a general high nitrogen burden that occurred at different sites and time points that could reflect the intense agricultural land use in the Nidda catchment as well as the relatively high content of treated wastewater. It is assumed that the average share of wastewater emitted by wastewater treatment plants in relation to the total discharge of the Nidda amounts to 15–26% [37, 122].

Chemical analyses

Water was analysed for 38 rather polar emerging contaminants, including pesticides, pharmaceuticals, artificial sweeteners and industrial chemicals (Additional file 2: Table S4).

Water samples generally showed increasing concentrations of wastewater-borne substances, such as most measured pharmaceuticals in a downstream direction, but particularly between N2 and N3, reflecting the increase in wastewater load discharged by the class-IV WWTP upstream N3 (Fig. 4). The inflow of the wastewater-impacted streams Horloff and Wetter upstream N6 further increased the contamination load which is reflected, e.g. by diclofenac (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug, NSAID) concentrations exceeding the currently discussed annual average environmental quality standard (AA-EQS) of 50 ng/L at N3 and N6. A previous study already showed that N6 is additionally influenced by specific compounds originating from industrial wastewater entering the Nidda via the Horloff tributary [58]. One of these compounds is the vulcanisation accelerator 1-o-tolylguanide which in the current study could be detected at N6 in water at concentrations of up to 200 ng/L (Additional file 2: Table S4) but also in sediment samples in concentrations up to 13 µg/kg (Additional file 2: Table S5). An influence of agriculture was hardly observed during the sampling campaigns, since pesticide residues were mainly detected in relatively low concentrations only. However, single high concentrations of certain pesticides (e.g. isoproturon, metamitron, terbuthylazine and metolachlor; Additional file 2: Table S4) indicated that the Nidda might be impacted by seasonal shock loads due to specific times of application and leaching as a consequence of heavy rainfalls, which would also fit to only partially elevated nitrate and nitrite levels.

Sediments were analysed for 26 mainly particle-associated pollutants (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and metal(loid)s and the total organic carbon (TOC) (Additional file 2: Table S5). Average concentrations of most of the analysed PAH and PCB were also higher at N3 and N6, but differences were less pronounced than for the wastewater-borne pollutants discussed above (Additional file 2: Table S5). However, single samples taken at N1 in February 2016 were polluted with PCBs even exceeding AA-EQS of 20 µg/kg [15], e.g. PCB 138 and PCB 153 (Fig. 5; Additional file 2: Table S5). A special source of metal(loid)s in the Nidda river basin is the water discharged from the mineral spa which reaches the river Nidda through the inflow of the river Wetter upstream of N6.

Concentrations of contaminants in Nidda sediments from N1, N2, N3 and N6 referring to kg dry weight; a fluoranthene; b benzo(a)pyrene; c HCB; d chromium; e copper; f lead; g nickel; h zinc and i sum of indicator PCBs. Metal(loid)s were analysed in the < 63 µm fraction. The six indicator PCBs include PCB 28, PCB 52, PCB 101, PCB 138, PCB 153 and PCB 180

Metal(loid) concentrations measured in the < 63 µm fractions of sediments were below defined EQS at all sampling sites, but arsenic and particularly zinc concentrations were elevated at N6, presumably as a result of the water from the mineral spa discharged by the Usa/Wetter system into the Nidda upstream N6. In contrast, chromium, copper, lead and nickel were detected at higher concentrations at N2 indicating potentially pollution from (former) industrial sources (Fig. 5).

Chemical analyses of fish muscle tissue from both actively exposed and feral fish focused on 45 substances with a high bioaccumulation potential, including PCBs, metal(loid)s and other semi-volatile organic pollutants, such as chlorobenzenes, HCH, HCB and DDT. Moreover, the synthetic musk compound (SMC) tonalide was analysed as a bioaccumulation substance, which in contrast to the other compounds is known to be discharged mainly by municipal WWTPs [27, 39]. Data are shown in Additional file 2: Table S6.

Apart from four chlorobenzene compounds and the delta isomers of HCH, all analysed substances were detected in at least one of the fish samples, but their dry weight concentrations were below the established biota environmental quality standards (EQS) and maximum residue limits (MRL) regarding fresh weight (fw) according to The European Parliament and the Council of the European Union and BMJV [14, 104]. Furthermore, a majority of PAHs were below the limits of quantitation (LOQ) at most sampling sites and time points.

In contrast to the scarcely detected PAHs, the concentrations of PCBs in fish were rather high. The maximum sum concentration of the seven indicator PCBs (PCB 52, PCB 101, PCB 138, PCB 153 and PCB 180) was detected in B. barbatula (Fig. 6a) and was as high as 340 µg/kg dw. According to EU recommendations for food safety, the maximum tolerable concentration for indicator PCBs in fish is 75 µg/kg fw [102]. Even though the water content of the fish samples was not determined within this study, it can be expected that the concentrations based on fresh weight were close to or even exceeded this threshold value.

Concentrations of contaminants in fish muscle tissue of caged O. mykiss from the CF and of field-captured B. barbatula from the FF monitoring in spring (FF1) and autumn (FF2) referring to kg dry weight (dw); a sum of indicator PCBs; b HCB; c tonalide; d arsenic; e chromium; f copper; g lead; h nickel and i zinc. The six indicator PCBs include PCB 28, PCB 52, PCB 101, PCB 138, PCB 153 and PCB 180. Concentrations in fish are based on pooled samples of eight individuals

Concerning the different contamination levels in relation with sampling sites, two patterns were observed. First, for PCBs, HCB, γ-HCH, DDT metabolites and tonalide concentrations increased from N1 to N6 in O. mykiss and mostly also in B. barbatula (Fig. 6a), although particularly PCB contamination of sediments barely differed between the sampling sites. Surprisingly, HCB and tonalide levels were considerably higher in caged O. mykiss than in feral B. barbatula, despite their rather short seven-week exposure time and lack of direct contact with the riverbed. Tonalide concentration in both species increased particularly from N2 to N3 reflecting the increase of wastewater discharged by the WWTP upstream N3. The trend of increasing PCB, HCB and tonalide concentrations downstream were still observed when concentrations were fat normalised, except for B. barbatula HCB levels (Additional file 2: Table S7). The second pattern showed specific increased contamination in fish from sampling sites N2 and partly N6. This concerned PCB contamination in S. trutta f. fario and L. cephalus, which was higher in individuals originating from N2 than either from N1 (S. trutta f. fario) or N6 (L. cephalus) (Additional file 2: Table S6), as well as metal(loid) contamination in general. Concerning the metal(loid) concentrations in fish muscle tissue, as expected, O. mykiss was considerably less contaminated than the chronically exposed field-captured fish and showed little variation between sites, except for chromium which was substantially elevated in individuals from N6 (Fig. 6d–i; Additional file 2: Table S6). In case of field-captured fish, particularly B. barbatula, a higher bioaccumulation of metal(loid)s was detected in individuals from N2 and N6. However, the contamination patterns detected in the sediment were only partially reflected in muscle tissue concentrations. In sediments, concentrations of chromium, nickel and zinc were > 100 mg/kg, while copper and lead ranged between 30 and 50 mg/kg. In fish muscle tissue, concentrations of chromium, copper, lead and nickel were rather low (< 2.5 mg/kg dw), whereas zinc levels were substantially higher.

Altogether, water samples generally showed increasing concentrations of wastewater-borne substances in a downstream direction matching the increased wastewater load mainly discharged by the WWTP upstream of N3. In sediments, particularly pollution with PCBs was mainly consistent across sites. However, PCB bioaccumulation in caged O. mykiss as well as field-captured B. barbatula increased at downstream sites. But in contrast to the general trend of increasing substance pollution and bioaccumulation in a downstream direction, the biological effects were severest in fish caged or caught at N2. Concerning the differences in species, sensitive S. trutta f. fario was impacted most and pelagic L. cephalus was less affected than benthic B. barbatula.

Discussion

Investigating the health status of caged and field-captured fish in the Nidda shed light on the biologically critical condition of fish in this river and confirmed its moderate to rather poor ecological status [15]. Furthermore, concerning the general condition of the Nidda, the results are in line with previously published data on developmental toxicity exerted by Nidda water and sediment in fish embryos [97], and invertebrate in vivo and in vitro assays [24].

Chemical analyses

Contamination of water and sediment samples as well as fish muscle tissue with anthropogenic pollutants showed different patterns in relation to the sampling sites.

In case of water pollution, contamination was clearly increasing in a downstream direction and was attributed to the increase in wastewater-borne substances related to discharges by municipal WWTPs and combined sewer overflows, including pharmaceuticals, artificial sweeteners as well as the synthetic musk compound (SMC) tonalide [26, 59], and additional industrial pollution indicated by the occurrence of specific industrial chemicals, like 1-o-tolylguanide [122]

In contrast, sediment contamination showed either only little variation between sites, e.g. in case of PAHs and PCBs, or site-specific increases in metal(loid) concentrations particularly at N2 and N6 indicating (former) industrial activities [11, 29, 48, 73]. In the specific case of N6, discharge of water from mineral spas may be added as additional source.

Concerning the contamination of fish muscle tissue, the detection frequency of PAHs was rather low, which may be explained by their high metabolisation and excretion rate [80]. The levels of PCBs, which show a much higher bioaccumulation potential than PAHs [5, 80], were considerably higher and on similar levels as in fish from knowingly PCB-polluted German rivers Rhine and Elbe (http://umweltprobenbank.de) and in one case (B. barbatula) might even exceeded the EU recommendations for food safety. The limit for indicator PCBs is set at 75 µg/kg fw [102], and based on a water content of 75–78% determined in the study of Boscher et al. [18], it can be assumed that a measured PCB concentration of 340 µg/kg dw is in the range of 75–85 µg/kg fw. In contrast to the rather constant PCB levels in the sediment, concentration in fish muscle tissue increased in a downstream direction. The trend of increasing PCB contamination of fish muscle tissue was still observed when concentrations were fat normalised (Additional file 1: Fig. S1).

Concentrations of HCB, HCH isomers as well as DDD, DDE and DDT isomers were rather low, at least compared to fish from larger rivers, like Rhine [49] and Elbe [62].

As expected and likely due to bioaccumulation over time, concentrations of pollutants, particularly PCBs, were considerably higher in field-captured fish than in caged O. mykiss. However, there were two exceptions. HCB and tonalide concentrations in O. mykiss were clearly above those from field-captured fish, particularly B. barbatula and L. cephalus, despite the short exposure time and no direct contact to the riverbed. Interestingly, concentrations for HCB in S. trutta f. fario were in the same range as in O. mykiss, but only in autumn. For lipophilic substances, tissue concentrations are likely correlated with lipid content. In case of HCB, this held true for O. mykiss with the highest lipid content, but lipid contents of S. trutta f. fario were in the range of the other field-captured fish. Although HCB is primarily contained in sediments, the considerably higher contents in some of the pelagic fish species indicate that at least the uptake of HCB is mediated rather through water than sediment entering the organisms via the gills or the skin [8, 60].

Histopathology

O. mykiss showed a considerable deterioration in their overall health condition after only seven weeks of exposure in the field compared to the fish kept in a hatchery. The gills and, particularly, the liver showed pronounced reactions including inflammations and necrosis. Feral fish chronically exposed to the Nidda water and sediment were affected even more severely. Regarding S. trutta f. fario and B. barbatula, the liver tissue was impacted more than the gills; for L. cephalus the opposite was the case.

Although being statistically significant for a single incident only (B. barbatula liver at sampling site N3), a general trend concerning seasonal differences was recognisable. Except for S. trutta f. fario, health condition was worse in June than in September. That might coincide with the spawning season of L. cephalus [66] and B. barbatula [100, 116], in which the fish allocate a high percentage of their energy resources to reproduction. In contrast, the breeding cycle of S. trutta f. fario follows almost an opposite regime with exogenous vitellogenesis starting in September and spawning season taking place in winter, ending in February [86]. Thus, reflecting that in seasons of high natural energy demands (e.g. spawning), fish in the Nidda are particularly susceptible and less resilient towards other stressors. Independent of the season, all species showed significant glycogen depletion in the liver, revealing a general loss of their energy reserves as a non-specific response to experienced stress that might enhance their susceptibility towards diseases, parasites and other forms of adverse biotic impact.

The differences in sensitivity between the species were particularly displayed by the conditions of the livers. Salmo trutta f. fario was affected most with all individuals showing at least severe reactions if not destruction of tissue integrity, whereas B. barbatula was in a slightly better condition but still impacted to a higher level than L. cephalus. Aside from S. trutta f. fario, which is known for its higher sensitivity compared to other freshwater species (e.g. [79, 88, 89]), it appears that the benthic species (B. barbatula) was more affected than the pelagic one (L. cephalus). This phenomenon has also been observed in a Nidda tributary, in which the histopathology revealed severer impact on the benthic gudgeon (Gobio gobio) than on the pelagic L. cephalus (own data, yet unpublished). Additionally, also fish embryo toxicity tests with Danio rerio (FET) conducted with water and sediment from the same sampling sites emphasised the importance of sediment as a sink for effect-inducing substances, since developmental toxicity was only detected in embryos exposed to samples containing river sediment [97]. Furthermore, the impact of contaminated sediments and suspended matter on fish populations has been investigated before, showing that sediments are of high relevance concerning fish abundance and health [23, 52, 76]. B. barbatula lives on the river bed, thus in close contact to the sediments, and forages on sediment-dwelling invertebrates [100] and has even shown to be comparably more affected than pelagic living species in the same river system [105].

EROD activity

In the Nidda sediments, PAH concentrations were rather low, whereas the PCB levels were elevated with single concentrations even exceeding AA-EQS. As PCBs are highly lipophilic organic pollutants metabolised in the liver, they are potent inducers of the cytochrome P-450 system to a large extent [1, 38, 56, 111]. In the case of the Nidda, constant PCB levels in the sediments contrasted the increasing bioaccumulation in fish, particularly in B. barbatula and O. mykiss in a downstream direction. Also, the extent of the PCB pollution in feral Nidda fish was comparable to bream (A. brama) caught in knowingly PCB-polluted rivers Rhine and Elbe (umweltprobenbank.de). Considering the rural character of the catchment and the rather small size of the Nidda compared to Rhine and Elbe, PCB levels were surprisingly high and might indicate contamination originating from former industrial production activities. Comparing B. barbatula with O. mykiss, PCB concentrations in B. barbatula were in general about twenty times higher than in O. mykiss, which might be due to (a) the short exposure of O. mykiss to the Nidda environment and (b) B. barbatula’s benthic way of living.

Compared to available data in literature, the measured EROD activity in the four investigated fish species, however, was rather low. In caged O. mykiss, the highest EROD activity was detected in the hatchery controls (0.7–1.1 pmol/min/mg), whereas in Nidda-exposed individuals, activities did not exceed 0.5 pmol/min/mg. In S. trutta f. fario individuals, EROD activity ranged between 0.5 and 1.5 pmol/min/mg, whereas Behrens and Segner [10] measured activities of 0.72 and 81.3 pmol/min/mg for laboratory control fish, and between 10.3 and 177.5 pmol/min/mg for field-exposed S. trutta f. fario. EROD activity in S. trutta f. fario exposed in a bypass system to water of one mildly (Argen) and one more heavily polluted river (Schussen) in Germany showed a significant contamination dependency. The EROD activity was in the range of 20 pmol/min/mg for the Argen fish and around 100 pmol/min/mg for the ones from the Schussen [65]. L. cephalus from different rivers in Italy, France, Romania, the Czech Republic and the UK showed values between 0.2 and 180 pmol/min/mg for individuals caught at reference sites and between 1 and 1061 pmol/min/mg for individuals from polluted areas [33, 35, 36, 41, 44, 57, 83, 114, 115, 126], whereas the EROD induction of individuals from the Nidda ranged between 0.5 and 0.6 pmol/min/mg. In B. barbatula, an EROD activity between 0.1 and 0.2 pmol/min/mg was induced, which is also below the activities of 3–63 pmol/min/mg for field-exposed fish detected by Behrens and Segner [9]. As a biochemical marker, however, EROD activity kinetics follow an optimum curve with increasing toxicity, meaning that the low EROD activities measured in Nidda-exposed fish could either be due to a lack of CYP1A1 induction or due to a system breakdown caused by capacity overload. Based on the fact that (a) in the CF monitoring, the highest EROD activity was detected in the hatchery controls and (b) the histopathology of both gills and, particularly, liver from caged as well as field-captured individuals showed severe pathological effects across all species, the conclusion of an overwhelmed hepatic CYP1A1 system seems plausibly standing to reason.

Micronucleus assay

In contrast to the dramatic effects observed for histopathology and EROD activity in general, the genotoxicity was within or even below the control ranges from laboratory exposures or field reference sites reported in literature: micronuclei frequencies of 0.33–2.31‰ for O. mykiss [4, 31, 32, 54, 94, 125], 0.7–2.87‰ for S. trutta f. fario [12], 0.2–8‰ for L. cephalus [36, 65, 77] and 0.5‰ for B. barbatula [105]. Despite the high impact of river water and sediment for fish health, thus genotoxicity obviously is not an issue in the Nidda River.

Differences in biological responses between sampling sites

Although N1 appeared to be less polluted compared to the sampling sites downstream, the occurrence of considerable histopathological effects in all three fish species clearly indicates that additional stressors at N1 were present. Since physicochemical parameters were in a normal range and habitat structure was more natural compared to the other sampling sites downstream, that relative “closeness to nature” implies further undetected chemical contamination.

At N2, conditions apparently changed severely, as the highest impact on fish health was observed. This held true for caged as well as field-captured species, particularly concerning the effects in the S. trutta f. fario livers which showed the severest effects of all examined samples. The EROD activity was particularly diminished (vs. the controls) across all species strongly supporting the assumption of an overwhelmed hepatic CYP1A1 system. Furthermore, the abundance of S. trutta f. fario was clearly reduced compared to N1 and the complete absence of the European bullhead (Cottus gobio), known for its sensitivity, was noted during the electrofishing events (Additional file 2: Table S7), although the habitat structure with higher stream velocity, shallow areas and a gravelly to stony riverbed would have suited this species [13, 34, 55, 69]. Compared to other sampling sites, N2 sediment showed elevated concentrations of some metal(loid)s, including chromium, copper, lead and nickel. Certain metal(loid)s are known to cause lesions in gills and in liver tissue, inducing, e.g. epithelial lifting in gills, congestion of blood vessels in liver as well as inflammations and necrosis in both liver and gills, e.g. [50, 82, 84, 108, 112]. However, the metal(loid) concentrations detected in the sediments were still below AA-EQS, if defined, and were only partially reflected in fish muscle tissue levels. Except for slightly elevated metal(loid) concentrations at N2 and/or N6, fish muscle tissue concentrations were not significantly varying between sampling sites. These results could either suggest different bioaccumulation potentials of the metal(loid)s in general or bioaccumulation in different tissues depending on the specific metal(loid). Pourang [81] investigated metal(loid) concentrations in several tissues of two different fish and observed varying levels depending on the metal(loid), the organ and the fish species. Concerning the investigated metal(loid)s, muscle tissue played a rather minor role in the total metal(loid) contamination of the fish [81]. Thus, regarding our study, the metal(loid) concentrations detected in the fish muscle tissue might not be sufficient to draw a comprehensive conclusion about the actually prevailing metal(loid) contamination but, nevertheless, might be an indication for relevant pollution. For example, the elevated concentrations of certain metal(loid)s at N2 in sediments as well as partially in fish muscle tissue might indicate (former) industrial pollution already in the upstream area which could contribute to the diminished health status observed in fish at N2. Besides the analysed metal(loid)s the chemical contamination at N2 could also comprise toxic compounds from other (industrial) sources which remained undetected, since they were not included in the chemical target analyses. This could, for example, include certain compounds in the effluents of local paper industry. Several studies with fish have already addressed the adverse effects of effluents from paper industry on physiological and biochemical functions, including damage of organ tissue [30, 53, 71, 75] and alterations in EROD activity [51, 72, 74, 98]. However, to identify further compounds which potentially contribute to the diminished health status at N2, a source-specific sampling campaign embedded in an extended chemical monitoring programme, ideally including also non-target screening approaches, would be needed.

Even though the chemical analyses clearly confirmed the increase of typical wastewater-borne compounds at N3, the caged O. mykiss and the caught B. barbatula were in a better condition than conspecifics at N2. Particularly remarkable, however, was the complete absence of L. cephalus in spring as well as in autumn, which was neither explicable by habitat structure nor by the measured chemicals.

Despite the circumstance that fish at N6 faced a combination of wastewater from Nidda, Horloff and Usa/Wetter tributary, encompassing discharges from municipal WWTPs, industry, intense agricultural land use and mineral spas, histopathological condition of feral L. cephalus and B. barbatula liver and gills and caged O. mykiss gills was slightly better at N2 and N3. Only the liver of O. mykiss individuals was affected to a higher extent in terms of a considerable depletion of glycogen. Such a loss of energy storage might have been caused by a higher current velocity observed at N6 during the caging experiments compared to the other sampling sites. In contrast to the feral fish that could move to sheltered areas, the caged O. mykiss were constantly forced to swim against the current.

Biological effects vs. chemical analyses

In the overall view of biological examinations and chemical analyses, it was most striking that the severest effects were not observed at the sampling site with the highest (detected) substance load (N6), but at a more upstream site (N2). The drastic biological responses in fish from N2 might be attributed to (a) a summary effect of a variety of substances [including metal(loid)s], (b) shock loads of specific substances, such as pesticides, and (c) non-measured or even unknown pollutants originating from recent or former (industrial) pollution. The absence of G. gobio despite the presence of a suitable habitat structure at N2 supports the assumption of a rather chemical-driven impact. The fact that (a) health status of fish from N1 and particularly from N2 was already considerably diminished and (b) health status even improves slightly at N3 compared to conspecifics from N2 indicates that, considering the increase of the proportion of wastewater from N2 to N3, typically wastewater-borne substances, such as pharmaceuticals, were not the main issue in this case. Furthermore, the average concentrations of the measured priority or river basin-specific pollutants were below their AA-EQS at N1 and N2. Even though not all compounds defined as priority or river basin-specific pollutants were analysed within this study, the results support the finding that monitoring of these well-known pollutants is not sufficient to address the chemical burden responsible for impaired fish health [97]. However, it would also be presumptuous to expect that a limited selection of substances is able to necessarily reflect a complete picture of the pollution situation and the corresponding effects on organisms. Particularly in the context of interacting factors and the issue of mixture toxicity, studies on organisms in the field are costly but indispensable due to their integrating character. Furthermore, in the future accompanying non-target screening approaches may lead to a more comprehensive picture of chemical burdens at different sites, e.g. [58], and may even be used to prioritise and identify unknown pollutants responsible for observed effects [106]. Although a cause–effect relationship could not be established, sediment contamination seems to be a key issue concerning fish health in the Nidda. Furthermore, it was shown that for certain substances (e.g. HCB, γ-HCH, tonalide) bioaccumulation has proven to occur extremely fast, meaning a rather short exposure time, like in the case of caged O. mykiss, was already sufficient to reach the detected contamination level of feral fish.

Further biological investigations of the Nidda catchment

Finally, comparing effects in adult fish to FET studies with Danio rerio at the same sampling sites [97] and the investigations of mortality and fecundity in Gammarus fossarum and Potamopyrgus antipodarum at two out of four sampling sites [N1, N6 (≙ N4 in Brettschneider et al. [24])], the histopathological and EROD activity results indicated a consistently diminished health condition in the entire water flow. Whereas the developmental toxicity (only in samples including sediments) was particularly high at sampling sites N1, N2 and N3, further downstream at N6, embryotoxic effects have been reported to be clearly reduced [97]. The opposite was observed in invertebrate assessment: G. fossarum and P. antipodarum were considerably less affected upstream (N1) than downstream (N6), coinciding with the additionally derived ecotoxicological status for river water, being better upstream than downstream, whereas the ecotoxicological potential of the sediment remained mediocre [24]. Thus, the invertebrate results were more in line with what would have been expected based on the chemical analyses, which in particular revealed an increase of compounds carried by communal and industrial wastewater along the river course. Increasing effects in invertebrates downstream indicate a higher sensitivity towards more polar wastewater-borne micropollutants. In contrast to the invertebrate results, the FET tests showed the same tendency as the histopathological examinations, with severer effects upstream than downstream, emphasising the importance of sediment contamination.

Implications for the WFD

Combining the results for invertebrates, fish embryos and adult fish, the adverse effects of Nidda river water and sediment contamination are evident for different organismic and trophic levels. However, chemical analyses of a huge variety of known pollutants were obviously insufficient to explain the severe biological impacts observed emphasising that EQS is only a first step in evaluating the toxicity of single substances. However, to adequately capture the actual exposure situation in a catchment with various contamination sources, focus should also be placed on the potential of effect-inducing compound mixtures. Thus, banning single specific substances from application is insufficient in most cases, particularly, as banned substances tend to be replaced by alternatives which might not be regulated but tackle the same target and thus likely induce similar effects [20]. In recent years, improvements of end of pipe solutions, e.g. upgrading of WWTPs, were shown to reduce contamination loads in surface waters [40] and mitigate effects in exposed organisms [107, 117]. Particularly, an application of activated carbon showed promising results concerning fish health, including improved organ integrity, lower hepatic hsp70 levels and an increased energy storage [124], as well as a decrease in genotoxicity and dioxin-like effects [125] in fish investigated after the upgrade compared to before. Furthermore, upgrading a WWTP with activated carbon promoted a recovery of the macrozoobenthos community and led to positive effects on fecundity and sex ratio of gammarids [78]. However, in a situation, like in the Nidda catchment, in which the first major WWTP discharges downstream the most affected site, a WWTP upgrade would mitigate the impact situation downstream, indeed, but would still be insufficient for the upstream contamination and demonstrates that contamination sources might be variable, not obvious or even undetected, so far.

Conclusion

Despite the apparent differences in results between the invertebrate, the FET and the fish biomarker studies recently published for in the anthropogenically influenced Nidda river, they (a) all showed that the it is still a long road to go to achieve a ‘good’ ecological status demanded by the EU according to the WFD, particularly when including fish health as a relevant parameter, (b) strengthened the view that results might diverge depending on the test species and endpoint but complement one another, (c) confirmed the awareness that ecosystem quality assessment cannot rely on chemical analytics alone and that the known pollutants included in the established target analytics might not be sufficient in explaining (substance related) effects in organisms, thus, (d) encouraged to apply methods, like non-target analytics, to identify previously undetected contamination sources and potentially reveal the underlying causes of observed health impairment of aquatic organisms and (e) emphasised that a healthy freshwater ecosystem cannot establish without considering the contamination of sediments. Thus, taking necessary actions to improve the ecological status of the respective water bodies must not solely focus on water quality but include steps to deal with the contamination of sediments, in which bioactive and persistent substances could have been accumulating for decades, to ensure a sustainable improvement of aquatic ecosystems in densely populated areas of industrialised countries. However, to comprehensively understand and interpret complex field data, that were also collected in this project, a significant improvement of knowledge regarding the interaction between substance loads, physicochemical conditions and morphological (habitat) structures influencing organisms’ well-being is still necessary.

Availability of data and materials

The data used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AA-EQS:

-

Annual average environmental quality standard

- dw:

-

Dry weight

- EROD:

-

7-Ethoxyresorufin-O-deethylase

- EQS:

-

Environmental quality standard

- FET test:

-

(Acute) fish embryo toxicity test

- fw:

-

Fresh weight

- HC:

-

Hatchery control

- HCB:

-

Hexachlorobenzene

- HCH:

-

Hexachlorocyclohexane

- HE stain:

-

Haematoxylin and eosin stain

- hpf:

-

Hours post fertilisation

- LOQ:

-

Limits of quantitation

- lw:

-

Lipid weight

- MRL:

-

Maximum residue limits

- PAH:

-

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons

- PAS stain:

-

Periodic acid-Schiff stain

- PCB:

-

Polychlorinated biphenyl

- pe:

-

People equivalents

- PHH:

-

Polyhalogenated hydrocarbons

- SVOC:

-

Semi-volatile halogenated compounds

- WFD:

-

Water Framework Directive

- WWTP:

-

Wastewater treatment plant

References

Addison RF, Zinck ME, Willis DE, Wrench JJ (1982) Induction of hepatic mixed function oxidase activity in trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) by Aroclor 1254 and some aromatic hydrocarbon PCB replacements. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 63(2):166–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/0041-008X(82)90037-0

Al-Sabti K, Metcalfe CD (1995) Fish micronuclei for assessing genotoxicity in water. Mutat Res Genet Toxicol 343(2–3):121–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1218(95)90078-0

Altenburger R, Brack W, Burgess RM, Busch W, Escher BI, Focks A, Mark Hewitt L, Jacobsen BN, de Alda ML, Ait-Aissa S, Backhaus T, Ginebreda A, Hilscherová K, Hollender J, Hollert H, Neale PA, Schulze T, Schymanski EL, Teodorovic I, Tindall AJ, de Aragão UG, Vrana B, Zonja B, Krauss M (2019) Future water quality monitoring: improving the balance between exposure and toxicity assessments of real-world pollutant mixtures. Environ Sci Eur 31(1):12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-019-0193-1

Ayllón F, Garcia-Vazquez E (2001) Micronuclei and other nuclear lesions as genotoxicity indicators in rainbow trout Oncorhynchus mykiss. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 49(3):221–225. https://doi.org/10.1006/eesa.2001.2065

Bachour G, Failing K, Georgii S, Elmadfa I, Brunn H (1998) Species and organ dependence of PCB contamination in fish, foxes, roe deer, and humans. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 35(4):666–673. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002449900429

Ballesteros ML, Rivetti NG, Morillo DO, Bertrand L, Amé MV, Bistoni MA (2017) Multi-biomarker responses in fish (Jenynsia multidentata) to assess the impact of pollution in rivers with mixtures of environmental contaminants. Sci Total Environ 595:711–722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.03.203

Barišić J, Dragun Z, Ramani S, Filipović Marijić V, Krasnići N, Čož-Rakovac R, Kostov V, Rebok K, Jordanova M (2015) Evaluation of histopathological alterations in the gills of Vardar chub (Squalius vardarensis Karaman) as an indicator of river pollution. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 118:158–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2015.04.027

Baussant T, Sanni S, Skadsheim A, Jonsson G, Børseth JF, Gaudebert B (2001) Bioaccumulation of polycyclic aromatic compounds: 2. Modeling bioaccumulation in marine organisms chronically exposed to dispersed oil. Environ Toxicol Chem 20(6):1185–1195. https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.5620200607

Behrens A, Segner H (2001) Hepatic biotransformation enzymes of fish exposed to non-point source pollution in small streams. J Aquat Ecosyst Stress Recover 8(3):281–297. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1012927505504

Behrens A, Segner H (2005) Cytochrome P4501A induction in brown trout exposed to small streams of an urbanised area: results of a five-year-study. Environ Pollut 136(2):231–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2005.01.010

Bellucci LG, Frignani M, Paolucci D, Ravanelli M (2002) Distribution of heavy metals in sediments of the Venice Lagoon: the role of the industrial area. Sci Total Environ 295(1):35–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-9697(02)00040-2

Belpaeme K, Delbeke K, Zhu L, Kirsch-Volders M (1996) Cytogenetic studies of PCB77 on brown trout (Salmo trutta f. fario) using the micronucleus test and the alkaline comet assay. Mutagenesis 11(5):485–492. https://doi.org/10.1093/mutage/11.5.485

Blanck A, Tedesco PA, Lamouroux N (2007) Relationships between life-history strategies of European freshwater fish species and their habitat preferences. Freshw Biol 52(5):843–859. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2427.2007.01736.x

BMJV—Bundesministerium der Justiz für Verbraucherschutz (1999) Rückstandshöchstmengen-verordnung (RhmV): verordnung über höchstmengen an rückständen von pflanzenschutz—und schädlingsbekämpfungsmitteln in oder auf lebensmitteln (BGBl. I, Nr. 49). BMJV, Germany, pp 2082–2141

BMUB—Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz, Bau und Reaktorsicherheit (2016) Die wasserrahmenrichtlinie—Deutschlands gewässer 2015. BMUB, Germany

BMUB—Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz, Bau und Reaktorsicherheit (2016) Oberflächengewässerverordnung (OGewV) vom 20. Juni 2016 (BGBI. I S. 1373). BMUB, Germany, pp 1–81

Bols NC, Schirmer K, Joyce EM, Dixon DG, Greenberg BM, Whyte JJ (1999) Ability of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons to induce 7-ethoxyresorufin-o-deethylase activity in a trout liver cell line. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 44(1):118–128. https://doi.org/10.1006/eesa.1999.1808

Boscher A, Gobert S, Guignard C, Ziebel J, L’Hoste L, Gutleb AC, Cauchie H-M, Hoffmann L, Schmidt G (2010) Chemical contaminants in fish species from rivers in the North of Luxembourg: potential impact on the Eurasian otter (Lutra lutra). Chemosphere 78(7):785–792. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.12.024

Bozcaarmutlu A, Sapmaz C, Kaleli G, Turna S, Yenisoy-Karakaş S (2015) Combined use of PAH levels and EROD activities in the determination of PAH pollution in flathead mullet (Mugil cephalus) caught from the West Black Sea coast of Turkey. Environ Sci Pollut Res 22(4):2515–2525. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-014-3700-3

Brack W, Aissa SA, Backhaus T, Dulio V, Escher BI, Faust M, Hilscherova K, Hollender J, Hollert H, Müller C, Munthe J, Posthuma L, Seiler T-B, Slobodnik J, Teodorovic I, Tindall AJ, de Umbuzeiro AG, Zhang X, Altenburger R (2019) Effect-based methods are key. The European Collaborative Project SOLUTIONS recommends integrating effect-based methods for diagnosis and monitoring of water quality. Environ Sci Eur 31(1):10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-019-0192-2

Brack W, Escher BI, Müller E, Schmitt-Jansen M, Schulze T, Slobodnik J, Hollert H (2018) Towards a holistic and solution-oriented monitoring of chemical status of European water bodies: how to support the EU strategy for a non-toxic environment? Environ Sci Eur 30(1):33. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-018-0161-1

Bradford MM (1976) A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein dye binding. Anal Biochem 72(1–2):248–254. https://doi.org/10.1006/abio.1976.9999

Braunbeck T, Brauns A, Keiter S, Hollert H, Schwartz P (2009) Fischpopulationen unter stress—das beispiel des unteren Neckars. Environ Sci Eur 21(2):197–211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12302-009-0044-6

Brettschneider DJ, Misovic A, Schulte-Oehlmann U, Oetken M, Oehlmann J (2019) Detection of chemically induced ecotoxicological effects in rivers of the Nidda catchment (Hessen, Germany) and development of an ecotoxicological, Water Framework Directive-compliant assessment system. Environ Sci Eur. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-019-0190-4

Bucheli TD, Fent K (1995) Induction of cytochrome P450 as a biomarker for environmental contamination in aquatic ecosystems. Crit Rev Environ Sci Technol 25(3):201–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/10643389509388479

Buerge IJ, Buser H-R, Kahle M, Müller MD, Poiger T (2009) Ubiquitous occurrence of the artificial sweetener acesulfame in the aquatic environment: an ideal chemical marker of domestic wastewater in groundwater. Environ Sci Technol 43(12):4381–4385. https://doi.org/10.1021/es900126x

Buerge IJ, Buser H-R, Müller MD, Poiger T (2003) Behavior of the polycyclic musks HHCB and AHTN in lakes, two potential anthropogenic markers for domestic wastewater in surface waters. Environ Sci Technol 37(24):5636–5644. https://doi.org/10.1021/es0300721

Burkina V, Zamaratskaia G, Sakalli S, Giang PT, Kodes V, Grabic R, Velisek J, Turek J, Kolarova J, Zlabek V, Randak T (2018) Complex effects of pollution on fish in major rivers in the Czech Republic. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 164:92–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2018.07.109

Byrne P, Reid I, Wood PJ (2010) Sediment geochemistry of streams draining abandoned lead/zinc mines in central Wales: the Afon Twymyn. J Soils Sediments 10(4):683–697. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-009-0183-9

Castro AJG, Baptista IE, de Moura KRS, Padilha F, Tonietto J, de Souza AZP, Soares CHL, Silva FRMB, Van Der Kraak G (2018) Exposure to a Brazilian pulp mill effluent impacts the testis and liver in the zebrafish. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol 206–207:41–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpc.2018.02.005

Crespo S, Marlasca MJ, Sanpera C, Riva MC, Sala R (1998) Hepatic alterations and induction of micronuclei in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) exposed to a textile industry effluent. Histol Histopathol 13(3):703–712

De Flora S, Viganò L, D’Agostini F, Camoirano A, Bagnasco M, Bennicelli C, Melodia F, Arillo A (1993) Multiple genotoxicity biomarkers in fish exposed in situ to polluted river water. Mutat Res Genet Toxicol 319(3):167–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1218(93)90076-P

Devaux A, Flammarion P, Bernardon V, Garric J, Monod G (1998) Monitoring of the chemical pollution of the river Rhône through measurement of DNA damage and cytochrome P4501A induction in chub (Leuciscus cephalus). Mar Environ Res 46(1):257–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0141-1136(97)00105-0

Fischer S, Kummer H (2000) Effects of residual flow and habitat fragmentation on distribution and movement of bullhead (Cottus gobio L.) in an alpine stream. Assessing the ecological integrity of running waters. Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht

Flammarion P, Devaux A, Nehls S, Migeon B, Noury P, Garric J (2002) Multibiomarker responses in fish from the Moselle River (France). Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 51(2):145–153. https://doi.org/10.1006/eesa.2001.2134

Frenzilli G, Falleni A, Scarcelli V, Del Barga I, Pellegrini S, Savarino G, Mariotti V, Benedetti M, Fattorini D, Regoli F, Nigro M (2008) Cellular responses in the cyprinid Leuciscus cephalus from a contaminated freshwater ecosystem. Aquat Toxicol 89(3):188–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquatox.2008.06.016

Fuchs S, Ziegler S, Wander R (2018) Modellierung der siedlungsbedingten stoffeinträge und gewässerkonzentrationen im Nidda-Einzugsgebiet. Projektverbund NiddaMan, Frankfurt, pp 1–10

Gerhart EH, Carlson RM (1978) Hepatic mixed-function oxidase activity in rainbow trout exposed to several polycyclic aromatic compounds. Environ Res 17(2):284–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/0013-9351(78)90031-2