Abstract

The acetabular labrum is an important structure that contributes to hip joint stability and function. Diagnosing labral tears involves a comprehensive assessment of clinical symptoms, physical examinations, imaging examinations, and arthroscopic confirmation. As arthroscopy is an invasive surgery, adjuvant imaging of the acetabular labrum is increasingly imperative for orthopedists to diagnose and assess labral lesions prior to hip arthroscopy for surgical management. This article reviews the current imaging strategies for the evaluation of labrum lesions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The acetabular labrum, located at the rim of the acetabulum, is a fibrocartilaginous structure that plays a vital biomechanical role in the hip joint. This structure contributes to static joint stabilization and joint lubrication, as well as increasing the effective depth of acetabulum [1]. Studies have shown that the nerve endings observed in collagen fiber bundles of the labrum may participate in nociceptive and proprioceptive processes, which contribute to painful symptoms when labral tears occur [2]. Disrupted static stabilization, altered biomechanics, and joint surface abrasion caused by labral tears may lead to joint dysfunction, chondral lesions, and osteoarthritis [1].

The etiology of labral tears includes traumatic injuries, femoroacetabular impingement (FAI), capsular laxity, and dysplasia [3]. Traumatic injury from shearing forces may contribute to labral tears when the patient twists, pivots, or falls down. It was reported that injury to the anterosuperior labrum, caused by twisting or pivoting movements, was the most frequent injury in the North American population, while injury to the posterior labrum, caused by hyperflexion or squatting movements, was the most frequent injury in the Asian population [3]. Decreased joint clearance between the femoral head and acetabulum and abnormal bone morphology lead to cam and pincer impingement, the two types of FAI, which cause labral tears and cartilage degeneration. Capsular laxity, resulting from connective tissue disorders or excessive forceful rotation, subjects the labrum to abnormal stress and pathology and in turn promotes labrum tears. The labrum then loses its role as a seal to maintain negative intraarticular pressure [3]. Developmental dysplasia is the decreased coverage of the acetabulum to the femoral head, which causes instability that contributes to labral tears [4].

At present, the diagnosis of labral lesions is mainly based on clinical symptoms, physical examinations, imaging evidence, and the gold standard of arthroscopic confirmation. Clinical symptoms often present with hip or groin pain during activities or even at rest, usually accompanied by a number of mechanical symptoms such as clicking, locking, and/or instability [1]. The physical examinations include inspection, measurements, palpation, and specific testing. In some cases, nonspecific symptoms and physical examinations may not be consistent with imaging evidence. The diagnosis of labral tears therefore requires hip arthroscopy for final confirmation [1]. Hip arthroscopy is a developing technology used not only for gold-standard confirmation of labral lesions but also for treatment through different methodologies, such as debridement, repair, reconstruction, and augmentation. As arthroscopy is an invasive procedure with possible complications, imaging evaluation prior to surgical therapy has become an important strategy for assessment of surgical necessity and confirmation of operative methodology for patients with hip symptoms [1]. Magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA) has been recognized as the gold-standard tool for labral tears but is limited by its invasiveness and radiation exposure. Therefore, MRA has been gradually replaced by convenience and noninvasive magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which has a diagnostic value that is not as satisfactory as that of MRA. Other imaging tools also have merits and drawbacks. In this paper, we summarize the classification of labral lesions by imaging and arthroscopy. Then, we review the imaging strategies for the evaluation of labrum lesions.

Classification

Lage, in 1996, proposed an arthroscopic labral classification that included four types of tears: radial flap, radial fibrillated, longitudinal peripheral, and unstable labral [5]. Radial flap labral tears are related to damage to the free margin of the labrum and therefore form a radial flap (Fig. 1A). Radial fibrillated labral tears are caused by the degeneration of the labrum, and the damaged labrum forms the shape of a shaving brush (Fig. 1B). Longitudinal peripheral labral tears refer to longitudinal tears along the junction of the labrum and acetabulum (Fig. 1C). Unstable labral tears are caused by subluxation and dysfunction of the labrum (Fig. 1D) [5].

Beck classification divides the labral morphology into five levels [6]. Normal labrum presents as macroscopically sound labrum. The labral degeneration manifests as thinning or localized hypertrophy, fraying, and discoloration. When the labrum completely avulses from the acetabular rim, it is defined as a labral full-thickness tear. Detachment of the labrum is defined as the separation between acetabular and labral cartilage, while the labral attachment to bone is preserved. The final level is ossification, in which localized or circumferential labrum is ossified [6].

Czerny et al. put forward a classification into three stages based on MRA, each stage with two types [7]. The normal labrum on MRA presents as a triangular shape with homogeneous low signal intensity that is continuously attached to the acetabular margin without a notch or a sulcus. The labral recess, located between the joint capsule and the labrum, is seen as a linear collection when contrast material fills this area [7]. The stage 1A labrum has a complete triangular morphology with an increased signal intensity in the center of the labrum and no sulcus at the junction of acetabular margin and labrum, and the labral recess still discernable, whereas in stage 1B the labrum is thickened and no labral recess is present [7]. The stage 2A labrum is an incomplete triangular shape with an extension of contrast material into the labrum, and continuous attachment to the acetabular margin and labral recess exists. Stage 2B shows similar phenomena to stage 2A, but with thickened labrum and absent labral recesses [7]. In Stage 3A, the labrum has a completely triangular morphology detached from the acetabular margin, whereas in stage 3B, the labrum is thickened with an increased signal intensity in the center of the labrum and detached from the acetabular margin [7].

Recently, Yoon et al. proposed a grading system to classify labral tears with hip dysplasia, which includes four grades based on disruptions of the chondrolabral junction (CLJ), capsulolabral recess (CLR), labral displacement, and instability of the torn labrum [8].

Radiography

Radiography of the pelvis in hip pain is commonly used to evaluate abnormal bone morphology such as FAI, structural instability, and hip dysplasia [9, 10]. Plain radiographs, including anteroposterior (AP) pelvis, frog leg lateral, cross table lateral, and Dunn view, are taken to measure the lateral center edge angle (LCEA), acetabular inclination, acetabular crossover, and femoral neck-shaft angle [9, 10].

The radiographic risk factors for FAI or hip dysplasia can help to guide the evaluation of labral tears as well. The labral tear size is reported to be correlated with femoral morphologic characteristics, alpha angle, neck-shaft angle, and cam lesions [10]. To exclude dysplasia cases, the lower the neck-shaft angles are in female patients, the larger the labral tears were detected [10]. Larger lesions were also associated with labral detachment and chondral defects [11]. Although the relationship between radiography and labral tears is obvious, changes in the labrum and cartilage cannot be seen directly due to the low resolution of radiography for soft tissues [12]. Therefore, further imaging evaluation strategies remain imperative for labral tear diagnosis.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

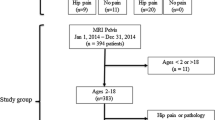

MRI has been recognized as a regular noninvasive and non-ionizing detection method for labrum tears as it can distinguish and characterize soft tissues via exquisite contrast resolution [1, 13]. On MRI, the normal labrum is a pointed triangular shape with sharp margins in low signal intensity. It is continuously attached to the acetabular margin and connects to the acetabular cartilage [1]. Morphological changes in the labrum include changes in size, globularization, signal changes (which may represent degeneration), tearing, and detachment of the labrum [1] (Fig. 2). MRI also shows the injury locations on the clock face of the acetabular rim and can be used to measure the labral width, which achieves strong consistency with arthroscopic findings of labrum size at different positions [13]. This accurate information achieved preoperatively can greatly improve operative choices.

The multiplanar image acquisition of MRI includes true axial, sagittal, and coronal planes. However, these planes may not be able to show the small, variably positioned and intraarticular labra. Instead, those images are recommended to be obtained via oblique planes relative to the acetabular rim [1]. The development of high-resolution and multiplanar reformatted (MPR) images improved the accuracy of MRI in labral tear detection. Mayer et al. compared different sequences of MRI protocols and found that three-dimensional (3D) imaging with multiplanar reformats (3D MPR) and radially reformatted (RR) imaging can present sufficiently sensitive and accurate MRI images for diagnosis [14].

The MRI pulse sequence relies on a variable-developing technique. The regular sequences include spin-echo, fast-spin-echo, gradient-recalled-echo, etc. The double-echo steady-state (DESS) MR sequence with water excitation can provide high-resolution 3D imaging and multiplanar reformatting, and an arthrogram-like image performs sensitive and specific detection for labrum pathology [15].

The field strength can also contribute to MRI imaging parameters. Schmitz et al. used optimized, noncontrast 1.5-T MRI to identify labral tears and paralabral cysts [16]. Sundberg et al. showed the superiority of 3.0-T MRI over 1.5-T MRI in arthrography of the acetabular labrum [17]. Chang et al. proposed an MRI protocol of the hip at 7 T and showed high-resolution labrum imaging [18].

Although high accuracy of detection for labral lesions can be achieved by MRI, several problems remain regarding anatomic variation. For instance, the sublabral sulcus may be mistakenly identified as a labral lesion on hip MRI images [19]. Another essential issue is postoperative evaluation for repaired labra, which is important for assessing surgical effects. Researchers found that evaluation of the morphology of postoperative labra consistent with preoperative labral tears was difficult for radiology assessments [20].

Magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA)

MRA is the visual optimization of MRI via diluted gadolinium-based contrast agents, which enhances the detection of intraarticular structures [21]. Petersilge et al. performed MRA in the axial, sagittal, and coronal planes. They developed a criteria for labral tears divided into labral blunting, absence, displacement, intrasubstance contrast material, and contrast material at the acetabular–labral junction, and confirmed the MRA findings via hip arthroscopy [22]. Czerny et al. correlated MRA images with surgical results and cadaveric joint specimens. The T1-weighted 3D gradient-echo sequences of MRA had 91% sensitivity, 71% specificity, and 88% accuracy [23].

The varied MRI protocols also produce differences in MRA image acquisitions. The sequences of coronal T2-weighted, axial oblique T1-weighted, and sagittal T1-weighted sequences covered a 95% detection rate of labral tears [24]. Three-dimensional steady-state free precession (3D-SSFP) MRA showed great superiority to 2D conventional MRI [25, 26]. MRA with axial leg traction was able to achieve separated acquisitions of tissue layers, which enabled a high rate of sensitivity and accuracy [27].

Direct MRA is a technology that combines intraarticular injection of contrast agents with MRI, and is commonly used to evaluate the acetabulum labrum. MRA improves spatial and contrast resolution by separating the capsular, labral, and osteochondral structures, as well as outlining the normal structures and pathological changes. This provides information to surgeons for decision making, portal selection, and labral tear localization [1]. The sensitivity and accuracy of MRA for labrum detection were 100% and 94%, respectively [28], which is superior to conventional MRI [29].

MRA is useful in the arthroscopic detection of suspected recurrent labral tears after labral resection. The resected labra are shortened, and recurrent labral tears appear as a new line to the surface [30]. It can also be applied in distinguishing labral lesions in patients with revision hip arthroscopy [31]. However, it cannot be considered a good choice for postoperative assessment of repaired labrum because of the possibility of misinterpreting a healed labrum [32].

The pitfall of direct MRA lies in the technological requirements and radiation exposure. MRA has a steep technological learning curve, and experienced physicians are needed for intraarticular injection and coordination with MRI. Radiation exposure and the risk of complications also limit the application of MRA [1]. Reurink et al. considered MRA to have a limited complementary benefit for diagnosis when used in patients with high clinical suspicion for labral tears. It cannot be used to rule out labral tears and conduct treatment strategies owing to its poor negative predictive value [33]. Keeney et al. also compared MRA findings with arthroscopy results and showed its limited sensitivity to false negatives of labral tears, which can be identified arthroscopically [34]. On the other hand, MRA imaging can be used for distinguishing sublabral recesses and labral tears [35]. The sublabral sulcus may also be misdiagnosed on MRA, which commonly appears at the posteroinferior acetabulum, whereas labral tears are mostly located at the anterior and anterosuperior acetabulum [36].

Indirect MRA involves intravenous contrast injection and a variable delay or physical activity prior to MRI. It not only enhanced contrast resolution between the labrum and other tissues, but also increases the radiographic identification of extraarticular soft tissue and vascular structures [1]. Zlatkin et al. retrospectively found 100% accuracy of labral tear evaluation with indirect MRA [37]. Pozzi et al. also showed a sensitivity of 88% and accuracy of 90% in detecting labral pathology with indirect MRA [38]. Hence, indirect MRA may be a good alternative strategy for direct MRA, but still needs a larger population of patients to confirm its utility.

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography has the potential ability to detect labral lesions in the hip, and has advantages with regard to safety, noninvasiveness, sensitivity, and inexpensiveness [39] (Fig. 3). Although early data reported an unsatisfactory sensitivity rate of ultrasound in labral tear diagnostics [40], a recent study showed a high sensitivity rate of ultrasound (US) imaging for the diagnosis of labral tears [39]. Ultrasound-guided hip injection further increased the accuracy for detecting intraarticular abnormality [41]. The improved accuracy may be attributable to technological updates and increased experience of operators [39, 42]. Ultrasound-assisted physical examination can also be used in screening programs to identify hip joint pathologies in high-risk groups [43]. Therefore, ultrasonography is a desirable diagnostic method, but relies on the operators’ learning curve and experience. The poor visibility of anatomic structures in obese patients is also a limitation for its use [39]. Therefore, ultrasonography is a desirable diagnostic method that relies on the operators’ learning curve and experience. The poor visibility of anatomic structures in obese patients also limits the application of ultrasonography [44].

Computed tomography (CT)

CT and multiplanar reconstruction CT (mCT) are considered more precise measurements for the detection of bone morphology and joint space than radiographs [45]. The cam-type deformity and pincer-type lesions seen on CT are related to the labrum tear and act as predictors for labral tears, although they cannot provide direct indication [45, 46]. Dolan et al. evaluated structural abnormalities with anterior center-edge angles, lateral center-edge angles, alpha angles, and neck-shaft angles. They found that 90% of patients with labral tears had structural abnormalities seen on CT scans [47].

Computed tomography arthrography (CTA)

CTA has already shown capabilities for high-resolution images of soft tissues, e.g., the anterior cruciate ligament and meniscus [48]. Nishii et al. used isotropic CTA with the radial reformation technique and divided acetabular weight-bearing areas into six zones. Different zones identified in CTA images localized the labral tears in hip pathology [49]. Yamamoto et al. also used radial contrast-enhanced CT for the diagnosis of acetabular labra and achieved an over 90% positive rate [50]. Researchers have demonstrated that CTA has higher sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy for detection of acetabular labral lesions than MRI [51] and MRA [52]. Multidetector CT (MDCT) arthrography also demonstrated accurate detection for labral lesions [53]. For postoperative assessment, Yoo et al. also performed postoperative CTA to assess anatomic changes, such as the width and height of the labrum [54].

However, CT arthrography is an invasive procedure with radiation exposure dose that is comparable to that of chest CT and coronary angiography [55]. Due to this concern, Tobalem et al. decreased the radiation dose level in hip MDCT arthrography through use of the adaptive statistical iterative reconstruction (ASIR) technique and achieved increments in image quality while maintaining diagnostic capability [56]. These inspiring results provide a promising direction for future studies of the utility of CTA for labral detection.

Conclusions

Adjuvant imaging of the acetabular labrum is increasingly imperative for orthopedists to diagnose and assess labral lesions prior to hip arthroscopy in order to determine the surgical requirements and choice of surgical method. Radiography, ultrasonography, and CT may not provide direct imaging symptoms for diagnosis. MRI is highly recommended for its convenience, effectiveness, and noninvasiveness; however, its diagnostic value is not as satisfactory as that of MRA. MRA is regarded as the gold-standard method for diagnosis of labral lesions, but is limited by its invasiveness and radiation exposure. The diagnostic value of CTA still needs further investigation to improve its utility. We summarize the characteristics of each strategy in Table 1 based on the papers we have reviewed. Despite the continuous development of imaging strategies, indirect visualization is always a limitation for final confirmation or in difficult and complicated cases that eventually require arthroscopy to achieve direct vision. Hence, future studies of techniques for imaging of labral pathology will need to determine the accuracy, sensitivity, and safety of imaging strategies. Multidimensional reconstruction of soft tissues, image separation of different soft tissues, and specific diagnosis of pathologic images may be direction for future efforts regarding acetabular labral imaging.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- FAI:

-

Femoroacetabular impingement

- MRA:

-

Magnetic resonance arthrography

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- CLJ:

-

Chondrolabral junction

- CLR:

-

Capsulolabral recess

- AP:

-

Anteroposterior

- LCEA:

-

Lateral center edge angle

- 3D MPR:

-

Three-dimensional (3D) imaging with multiplanar reformats

- RR:

-

Radially reformatted

- DESS:

-

Double-echo steady-state

- 3D-SSFP:

-

3D steady-state free precession

- 2D-TSE-PD fs:

-

2D turbo spin-echo proton density-weighted fat-saturated

- FSE:

-

Fast spin-echo

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- mCT:

-

Multiplanar reconstruction CT

- CTA:

-

Computed tomography arthrography

- MDCT:

-

Multidetector CT

- ASIR:

-

Adaptive statistical iterative reconstruction

References

Rakhra KS (2011) Magnetic resonance imaging of acetabular labral tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am 93(2):28–34

Kim YT, Azuma H (1995) The nerve endings of the acetabular labrum. Clin Orthop Relat Res 320:176–181

Martin RL, Enseki KR, Draovitch P, Trapuzzano T, Philippon MJ (2006) Acetabular labral tears of the hip: examination and diagnostic challenges. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 36(7):503–515

Wenger DE, Kendell KR, Miner MR, Trousdale RT (2004) Acetabular labral tears rarely occur in the absence of bony abnormalities. Clin Orthop Relat Res 426:145–150

Lage LA, Patel JV, Villar RN (1996) The acetabular labral tear: an arthroscopic classification. Arthroscopy 12(3):269–272

Beck M, Kalhor M, Leunig M, Ganz R (2005) Hip morphology influences the pattern of damage to the acetabular cartilage: femoroacetabular impingement as a cause of early osteoarthritis of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br 87(7):1012–1018

Czerny C, Hofmann S, Neuhold A, Tschauner C, Engel A, Recht MP et al (1996) Lesions of the acetabular labrum: accuracy of MR imaging and MR arthrography in detection and staging. Radiology 200(1):225–230

Yoon PW, Moon JK, Yoon JY, Lee S, Lee SJ, Kim HJ et al (2020) A novel arthroscopic classification of labral tear in hip dysplasia. PLoS ONE 15(10):e0240993

Barton C, Salineros MJ, Rakhra KS, Beaulé PE (2011) Validity of the alpha angle measurement on plain radiographs in the evaluation of cam-type femoroacetabular impingement. Clin Orthop Relat Res 469(2):464–469

Redmond JM, Gupta A, Hammarstedt JE, Stake CE, Dunne KF, Domb BG (2015) Labral injury: radiographic predictors at the time of hip arthroscopy. Arthroscopy 31(1):51–56

Johnston TL, Schenker ML, Briggs KK, Philippon MJ (2008) Relationship between offset angle alpha and hip chondral injury in femoroacetabular impingement. Arthroscopy 24(6):669–675

Shang XL, Zhang JW, Chen JW, Li YX, Chen SY (2013) Features of acetabular labral tears on X-ray, magnetic resonance imaging and hip arthroscopy—the observational pilot study. Arch Med Sci 9(2):297–302

Kaplan DJ, Samim M, Burke CJ, Meislin RJ, Youm T (2020) Validity of magnetic resonance imaging measurement of hip labral width compared with intraoperative assessment. Arthroscopy 36(3):751–758

Mayer SW, Skelton A, Flug J, McArthur T, Hovater W, Carry P et al (2021) Comparison of 2D, 3D, and radially reformatted MR images in the detection of labral tears and acetabular cartilage injury in young patients. Skeletal Radiol 50(2):381–388

Schleich C, Hesper T, Hosalkar HS, Rettegi F, Zilkens C, Krauspe R et al (2017) 3D double-echo steady-state sequence assessment of hip joint cartilage and labrum at 3 Tesla: comparative analysis of magnetic resonance imaging and intraoperative data. Eur Radiol 27(10):4360–4371

Schmitz MR, Campbell SE, Fajardo RS, Kadrmas WR (2012) Identification of acetabular labral pathological changes in asymptomatic volunteers using optimized, noncontrast 1.5-T magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Sports Med 40(60):1337–1341

Sundberg TP, Toomayan GA, Major NM (2006) Evaluation of the acetabular labrum at 3.0-T MR imaging compared with 1.5-T MR arthrography: preliminary experience. Radiology 238(2):706–711

Chang G, Deniz CM, Honig S, Egol K, Regatte RR, Zhu Y et al (2014) MRI of the hip at 7T: feasibility of bone microarchitecture, high-resolution cartilage, and clinical imaging. J Mag Reson Imaging 39(6):1384–1393

Nguyen MS, Kheyfits V, Giordano BD, Dieudonne G, Monu JU (2013) Hip anatomic variants that may mimic abnormalities at MRI: labral variants. AJR Am J Roentgenol 201(3):W394-400

Foreman SC, Zhang AL, Neumann J, von Schacky CE, Souza RB, Majumdar S et al (2020) Postoperative MRI findings and associated pain changes after arthroscopic surgery for femoroacetabular impingement. AJR Am J Roentgenol 214(1):177–184

Sconfienza LM, Albano D, Messina C, Silvestri E, Tagliafico AS (2018) How, when, why in magnetic resonance arthrography: an International Survey by the European Society of Musculoskeletal Radiology (ESSR). Eur Radiol 28(6):2356–2368

Petersilge CA, Haque MA, Petersilge WJ, Lewin JS, Lieberman JM, Buly R (1996) Acetabular labral tears: evaluation with MR arthrography. Radiology 200(1):231–235

Czerny C, Hofmann S, Urban M, Tschauner C, Neuhold A, Pretterklieber M et al (1999) MR arthrography of the adult acetabular capsular-labral complex: correlation with surgery and anatomy. AJR Am J Roentgenol 173(2):345–349

Ziegert AJ, Blankenbaker DG, De Smet AA, Keene JS, Shinki K, Fine JP (2009) Comparison of standard hip MR arthrographic imaging planes and sequences for detection of arthroscopically proven labral tear. AJR Am J Roentgenol 192(5):1397–1400

Kraus MS, Notohamiprodjo M, Partovi S, Sobieh A, Baur-Melnyk A, Hausdorf J et al (2018) MR arthrography of the hip: diagnostic performance and image quality of 3D-steady state free precession versus 2D turbo spin echo sequences. Skeletal Radiol 47(6):811–819

Park SY, Park JS, Jin W, Rhyu KH, Ryu KN (2013) Diagnosis of acetabular labral tears: comparison of three-dimensional intermediate-weighted fast spin-echo MR arthrography with two-dimensional MR arthrography at 30 T. Acta Radiol (Stockholm, Sweden: 1987) 54(1):75–82

Schmaranzer F, Klauser A, Kogler M, Henninger B, Forstner T, Reichkendler M et al (2015) Diagnostic performance of direct traction MR arthrography of the hip: detection of chondral and labral lesions with arthroscopic comparison. Eur Radiol 25(6):1721–1730

Chan YS, Lien LC, Hsu HL, Wan YL, Lee MS, Hsu KY et al (2005) Evaluating hip labral tears using magnetic resonance arthrography: a prospective study comparing hip arthroscopy and magnetic resonance arthrography diagnosis. Arthroscopy 21(10):1250

Saied AM, Redant C, El-Batouty M, El-Lakkany MR, El-Adl WA, Anthonissen J et al (2017) Accuracy of magnetic resonance studies in the detection of chondral and labral lesions in femoroacetabular impingement: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 18(1):83

Blankenbaker DG, De Smet AA, Keene JS (2011) MR arthrographic appearance of the postoperative acetabular labrum in patients with suspected recurrent labral tears. AJR Am J Roentgenol 197(6):W1118–W1122

McCarthy JC, Glassner PJ (2013) Correlation of magnetic resonance arthrography with revision hip arthroscopy. Clin Orthop Relat Res 471(12):4006–4011

Aprato A, Jayasekera N, Villar RN (2013) The accuracy of magnetic resonance arthrography in hip arthroscopic labral revision surgery. Hip Int 23(1):99–103

Reurink G, Jansen SP, Bisselink JM, Vincken PW, Weir A, Moen MH (2012) Reliability and validity of diagnosing acetabular labral lesions with magnetic resonance arthrography. J Bone Joint Surg Am 94(18):1643–1648

Keeney JA, Peelle MW, Jackson J, Rubin D, Maloney WJ, Clohisy JC (2004) Magnetic resonance arthrography versus arthroscopy in the evaluation of articular hip pathology. Clin Orthop Relat Res 429:163–169

Studler U, Kalberer F, Leunig M, Zanetti M, Hodler J, Dora C et al (2008) MR arthrography of the hip: differentiation between an anterior sublabral recess as a normal variant and a labral tear. Radiology 249(3):947–954

Dinauer PA, Murphy KP, Carroll JF (2004) Sublabral sulcus at the posteroinferior acetabulum: a potential pitfall in MR arthrography diagnosis of acetabular labral tears. AJR Am J Roentgenol 183(6):1745–1753

Zlatkin MB, Pevsner D, Sanders TG, Hancock CR, Ceballos CE, Herrera MF (2010) Acetabular labral tears and cartilage lesions of the hip: indirect MR arthrographic correlation with arthroscopy—a preliminary study. AJR Am J Roentgenol 194(3):709–714

Pozzi G, Stradiotti P, Parra CG, Zagra L, Sironi S, Zerbi A (2009) Femoro-acetabular impingement: can indirect MR arthrography be considered a valid method to detect endoarticular damage? A preliminary study. Hip Int 19(4):386–391

Orellana C, Moreno M, Calvet J, Navarro N, García-Manrique M, Gratacós J (2019) Ultrasound findings in patients with femoracetabular impingement without radiographic osteoarthritis: a Pilot study. J Ultrasound Med 38(4):895–901

Troelsen A, Jacobsen S, Bolvig L, Gelineck J, Rømer L, Søballe K (2007) Ultrasound versus magnetic resonance arthrography in acetabular labral tear diagnostics: a prospective comparison in 20 dysplastic hips. Acta Radiol (Stockholm, Sweden: 1987) 48(9):1004–1010

Gao G, Fu Q, Wu R, Liu R, Cui L, Xu Y (2020) Ultrasound and ultrasound-guided hip injection have high accuracy in the diagnosis of femoroacetabular impingement with atypical symptoms. Arthrosc J Arthrosc Rel Surg Off Publ Arthrosc Assoc N Am Int Arthrosc Assoc 37:128–135

Troelsen A, Mechlenburg I, Gelineck J, Bolvig L, Jacobsen S, Søballe K (2009) What is the role of clinical tests and ultrasound in acetabular labral tear diagnostics? Acta Orthop 80(3):314–318

Rodriguez M, Bolia IK, Philippon MD, Briggs KK, Philippon MJ (2019) Hip screening of a professional ballet company using ultrasound-assisted physical examination diagnosing the at-risk hip. J Dance Med Sci 23(2):51–57

Jin W, Kim KI, Rhyu KH, Park SY, Kim HC, Yang DM et al (2012) Sonographic evaluation of anterosuperior hip labral tears with magnetic resonance arthrographic and surgical correlation. J Ultrasound Med 31(3):439–447

Aiba H, Watanabe N, Fukuoka M, Wada I, Murakami H (2019) Radiographic analysis of subclinical appearances of the hip joint among patients with labral tears. J Orthop Surg Res 14(1):369

Heyworth BE, Dolan MM, Nguyen JT, Chen NC, Kelly BT (2012) Preoperative three-dimensional CT predicts intraoperative findings in hip arthroscopy. Clin Orthop Relat Res 470(7):1950–1957

Dolan MM, Heyworth BE, Bedi A, Duke G, Kelly BT (2011) CT reveals a high incidence of osseous abnormalities in hips with labral tears. Clin Orthop Relat Res 469(3):831–838

Vande Berg BC, Lecouvet FE, Poilvache P, Dubuc JE, Maldague B, Malghem J (2002) Anterior cruciate ligament tears and associated meniscal lesions: assessment at dual-detector spiral CT arthrography. Radiology 223(2):403–409

Nishii T, Tanaka H, Sugano N, Miki H, Takao M, Yoshikawa H (2007) Disorders of acetabular labrum and articular cartilage in hip dysplasia: evaluation using isotropic high-resolutional CT arthrography with sequential radial reformation. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 15(3):251–257

Yamamoto Y, Tonotsuka H, Ueda T, Hamada Y (2007) Usefulness of radial contrast-enhanced computed tomography for the diagnosis of acetabular labrum injury. Arthroscopy 23(12):1290–1294

Lee GY, Kim S, Baek SH, Jang EC, Ha YC (2019) Accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography arthrography in diagnosing acetabular labral tears and chondral lesions. Clin Orthop Surg 11(1):21–27

Perdikakis E, Karachalios T, Katonis P, Karantanas A (2011) Comparison of MR-arthrography and MDCT-arthrography for detection of labral and articular cartilage hip pathology. Skeletal Radiol 40(11):1441–1447

Christie-Large M, Tapp MJ, Theivendran K, James SL (2010) The role of multidetector CT arthrography in the investigation of suspected intra-articular hip pathology. Br J Radiol 83(994):861–867

Yoo JI, Ha YC, Lee YK, Lee GY, Yoo MJ, Koo KH (2017) Morphologic changes and outcomes after arthroscopic acetabular labral repair evaluated using postoperative computed tomography arthrography. Arthroscopy 33(2):337–345

Mettler FA Jr, Huda W, Yoshizumi TT, Mahesh M (2008) Effective doses in radiology and diagnostic nuclear medicine: a catalog. Radiology 248(1):254–263

Tobalem F, Dugert E, Verdun FR, Dunet V, Ott JG, Rudiger HA et al (2014) MDCT arthrography of the hip: value of the adaptive statistical iterative reconstruction technique and potential for radiation dose reduction. AJR Am J Roentgenol 203(6):W665–W673

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81902303, 82072515), Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2020A151501048), Shenzhen Science and Technology Project (RCBS20200714114856299, JCYJ20190806164216661), and Clinical Research Project of Shenzhen Second People’s Hospital (20203357028).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YL and KO contributed to the conception and design of this review article. YL and ZD performed searches, analyses, and interpretations. YL and ZD drafted the paper. WL and ZD were responsible for funding collection. WL and KO gave final approval of the version to be submitted. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Lu, W., Ouyang, K. et al. The imaging evaluation of acetabular labral lesions. J Orthop Traumatol 22, 34 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s10195-021-00595-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s10195-021-00595-7