Abstract

Background

Clinical trials and real-world studies revealed a spectrum of response to CGRP(-receptor) monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) in migraine prophylaxis, ranging from no effect at all to total migraine freedom. In this study, we aimed to compare clinical characteristics between super-responders (SR) and non-responders (NR) to CGRP(-receptor) mAbs.

Methods

We performed a retrospective cohort study at the Headache Center, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin. The definition of super-response was a ≥ 75% reduction in monthly headache days (MHD) in the third month after treatment initiation compared to the month prior to treatment begin (baseline). Non-response was defined as ≤ 25% reduction in MHD after three months of treatment with a CGRP-receptor mAb and subsequent three months of treatment with CGRP mAb, or vice versa. We collected demographic data, migraine disease characteristics, migraine symptoms during the attacks in both study groups (SR/NR) as well as the general medical history. SR and NR were compared using Chi-square test for categorical variables, and t-test for continuous variables.

Results

Between November 2018 and June 2022, n = 260 patients with migraine received preventive treatment with CGRP(-receptor) mAbs and provided complete headache documentation for the baseline phase and the third treatment month. Among those, we identified n = 29 SR (11%) and n = 26 NR (10%). SR reported more often especially vomiting (SR n = 12/25, 48% vs. NR n = 4/22, 18%; p = 0.031) and typical migraine characteristics such as unilateral localization, pulsating character, photophobia and nausea. A subjective good response to triptans was significantly higher in SR (n = 26/29, 90%) than in NR (n = 15/25, 60%, p = 0.010). NR suffered more frequently from chronic migraine (NR n = 24/26, 92% vs. SR n = 15/29, 52%; p = 0.001), medication overuse headache (NR n = 14/24, 58% versus SR n = 8/29, 28%; p = 0.024), and concomitant depression (NR n = 17/26, 65% vs. SR n = 8/29, 28%; p = 0.005).

Conclusion

Several clinical parameters differ between SR and NR to prophylactic CGRP(-R) mAbs. A thorough clinical evaluation prior to treatment initiation might help to achieve a more personalized management in patients with migraine.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Monoclonal antibodies (mAb) against Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide (CGRP) and the CGRP-receptor (CGRP-R) are specific substances for the prophylactic treatment of migraine [1]. Clinical trials have demonstrated the efficacy, safety and favorable tolerability of CGRP(-R) mAbs in patients with episodic migraine (EM) and chronic migraine (CM) [2].

In the pivotal registration trials for the CGRP-R mAb erenumab, up to 50% of patients with EM and 41% of patients with CM reported a reduction in monthly migraine days (MMD) from baseline of at least 50% [3,4,5]. Studies with the CGRP mAbs galcanezumab and fremanezumab reached 50% responder rates of up to 62% in EM [6,7,8] and 41% in CM [9, 10]. Of note, trial designs and statistical analyses are not identical between studies and therefore numerical differences exist in the endpoint determination [3,4,5,6,7,8]. Even in patients with numerous unsuccessful prior preventive treatment attempts, CGRP(-R) mAbs led to a ≥ 50% response in one-third of cases [11,12,13]. Despite these favorable results, up to 20% of patients had no improvement with CGRP(-R) mAbs, showing no change or even an increase in MMD during these trials [14]. In contrast, a subgroup of trial participants showed an exceptionally good treatment response: Up to 39% of EM patients achieved a ≥ 75% decrease in MMD and up to 16% were completely migraine-free during the selected observation period [7, 14].

Real-world data with the use of CGRP(-R) mAbs in clinical practice show similar findings. About half of CM patients have a 50% reduction of MMD after three months of treatment [15, 16]. At the same time, up to one-third of patients do not respond to mAbs treatment, while 20% have a very high benefit with a reduction of ≥ 75% in MMD along a tremendous improvement of quality of life.

Despite several attempts, clear predictors of response could not be determined in the registration trials. In a few real-world studies, unilateral pain localization, and triptan responsiveness were positively associated with a better treatment response [17,18,19,20,21]. On the contrary, psychiatric comorbidities, a long disease duration and a high number of previously failed preventive treatments were associated with a lower response [17, 18, 22,23,24,25,26]. Additional file 1 provides an overview of current literature on predictors of response to treatment with CGRP(-R)-mAbs.

However, patients who have no improvement with mAbs prophylaxis and patients who respond exceptionally well have not been characterized to date. Clinical differences between non-responders (NR) and super-responders (SR) could help to facilitate a better tailored management of patients with migraine. In this study, we aim to perform a clinical evaluation of absolute NR and SR to CGRP(-R) mAbs and to compare clinical characteristics between these two groups.

Methods

Study design and participants

This was a retrospective cohort study at the tertiary Headache Center, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Germany. We screened the electronic charts of all patients with migraine who received prophylactic treatment with CGRP(-R) mAbs between November 2018 and June 2022. Due to reimbursement regulations in Germany at the time of this study, the prerequisites for mAb treatment were treatment failure or intolerable adverse events with all first-line preventives (beta-blockers, topiramate, flunarizine, amitriptyline and for CM also OnabotulinumtoxinA) or contraindications to those [27,28,29].

Super-Responder (SR) and Non-Responder (NR) were identified according to the following definitions:

-

SR: Patients with ≥ 75% reduction of monthly headache days (MHD) in the third month after mAb treatment initiation versus baseline (i.e. the four-week period prior to the first mAb injection or, if available, the average number of MHD of the last three months prior to the first mAb treatment).

-

NR: Patients who received a CGRP-R-mAb (erenumab) and subsequently a CGRP-mAb (galcanezumab or fremanezumab), or vice versa, and had a reduction in MHD of ≤ 25% between baseline and the third month of treatment with both mAb classes.

Headache data was assessed using standardized electronic or paper headache diaries that the patients routinely bring to every appointment. A month was defined as 28-day period, a headache day as any calendar day with a documented headache episode. When headache diaries were missing, we used the physician’s documentation in the electronic patient chart. Patients without any headache documentation for the period of interest were excluded from this analysis. Further exclusion criteria were: mAb treatment duration of less than three months, and prior participation in a registration trial with CGRP(-R) mAbs.

Evaluation of Super-Responders (SR) and Non-Responders (NR)

In the groups of SR and NR, we recorded basic demographic data, migraine history and characteristics as well as general medical history (Table 1).

A monthly migraine day (MMD) was defined as any calendar day with a headache fulfilling the International Classification of Headache Disorders-3 (ICHD-3) of migraine or probable migraine [30]. Non-migraine days (NMD) were defined as headache days that did not fulfill this criterion (NMD = MHD – MMD). Baseline period: For migraine symptoms during attacks, each item was considered positive if the majority of attacks displayed the respective feature.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 27. We used descriptive statistics to summarize demographic and anamnestic data (frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, mean ± standard deviation for numerical variables). Categorical variables were compared between groups using the Chi-square test, and continuous variables by t-test. A two-tailed p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Due to the exploratory approach of the study, data were not corrected for multiple testing. Numbers and percentages of missing values are provided for each variable.

Results

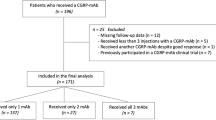

Between November 2018 and June 2022, n = 359 patients received at least one CGRP(-R) mAb as preventive treatment for migraine. Headache documentation for baseline and the third mAb treatment month was available for n = 260 patients. Of these, n = 29 (11%) and n = 26 (10%) met the predefined criteria of a SR or NR, respectively.

NR and SR did not differ significantly with respect to sex, age at initiation of mAb therapy, or duration of migraine in years (Table 2). In both NR and SR groups, erenumab was the most frequent mAb of first choice (Table 2). The class of the first used mAb (CGRP-R or CGRP mAb) did not differ between NR and SR (NR CGRP-R mAb n = 14/26, 54% vs. SR CGRP-R-mAb n = 12/29, 41%; p = 0.35).).

Headache characteristics

NR suffered significantly more often from CM than SR (NR n = 24/26, 92% vs. SR n = 15/29, 52%; p = 0.001). Accordingly, the number of MHD (NR 18.2 ± 6.8 vs. SR 11.4 ± 4.5, t = 4.4, p < 0.001) and MMD (NR 14.1 ± 6.4 vs SR 10.6 ± 4.7, t = 2.2, p = 0.035) during baseline were significantly higher in NR than in SR (Fig. 1). NR suffered also from more NMD at baseline, although without statistical significance (NR 3.5 ± 6.7 vs. SR 0.8 ± 2.2, t = 1.98, p = 0.054). Typical migraine characteristics such as unilateral localization, pulsating character, photophobia, nausea or vomiting occurred numerically more frequently in SR than NR (Table 3), but statistical significance was only reached for the occurrence of vomiting (NR n = 4/22, 18% vs. SR n = 12/25, 48%; p = 0.031).

Migraine specific medication

Both patient groups used triptans as acute migraine medication (NR n = 25/26, 98%, and SR n = 29/29, 100%). However, SR were significantly more likely to report sufficient improvement of their acute migraine headache after triptan intake (n = 26/29, 90%) compared to NR (n = 15/25, 60%, p = 0.010). The number of pharmacological prophylactic treatment regimens prior to CGRP(-R) mAb therapy did not differ significantly between NR and SR (NR 4.9 ± 1.8 vs. SR 4.8 ± 2.2, p = 0.8).

Comorbidities

NR suffered significantly more often from concomitant depression than SR (NR n = 17/26, 65% vs. SR n = 8/29, 28%; p = 0.005) (Fig. 1). Medication overuse headache (MOH) prior to treatment begin was also statistically significantly more frequent in NR than SR (NR n = 14/24, 58% versus SR n = 8/29, 28%; p = 0.024). Other comorbidities, such as anxiety disorders or other chronic pain disorders, did not differ significantly.

Follow-up therapy in non-responders

In NR, therapy was switched to the third and at this time last available CGRP-(R) mAb in 31% of cases (n = 8/26). In 19% (n = 5/26), the most recent CGRP-(R) antibody therapy was continued due to subjective headache improvement, e.g. reported improvement in headache intensity or a better response to acute headache medication. Figure 2 shows the follow-up treatment strategies in NR.

Discussion

In this retrospective real-world study, we identify clinical characteristics of super-responders (SR) and absolute non-responders (NR) to CGRP(-R) mAbs. Migraine attacks in SR were numerically more likely to present with typical migraine features such as unilateral localization, pulsating character, nausea, and vomiting than in NR, with only vomiting reaching statistical significance. Conversely, NR had twice as often chronic migraine (CM), medication-overuse headache (MOH) and suffered from depression in comparison to SR.

Due to regulatory requirements in Germany [27,28,29], treatment with CGRP(-R) mAbs at the time of this study was reimbursed only in patients with treatment-resistant migraine [31]. Response to CGRP(-R)-mAbs was shown to be better in patients with a lower number of unsuccessful prophylactic treatment attempts [16, 18, 25, 32], but even in this difficult-to-treat population, 11% of patients showed an excellent clinical response to CGRP(-R) mAbs with a ≥ 75% reduction in headache frequency. This is lower than in cohorts with less treatment-experienced patients [3,4,5,6,7,8] but still remarkable for patients who have lived with migraine for decades and failed all preventives of first choice. In this subgroup of patients, CGRP seems to be the driving force for migraine attack generation. Accordingly, in a Danish study, patients with an excellent response to erenumab were also highly susceptible to intravenous CGRP provocation, suggesting CGRP to be the key pathophysiological pathway in this clinical phenotype (“CGRP phenotype”) [33]. Migraine-specific acute medications such as triptans also act on the CGRP pathway [1]. Triptans target mainly the 5-HT1B and 5-HT1D receptor subtypes, located at meningeal vessels but also within the trigeminal nerve endings and trigeminal nucleus and suppresses the release of CGRP [34, 35]. Typical accompanying symptoms of migraine such as photophobia or vomiting are also mediated by CGRP and relieved by both triptans and CGRP(-R) mAbs [36, 37]. In the presented study, consistent with previous publications [20, 38], a good subjective response to acute therapy with triptans was reported significantly more often by SR. SR also reported more typical concomitant symptoms, in particular vomiting. Both findings are in line with the assumption that CGRP plays a central role in migraine initiation in this subgroup.

On the other side, in 10% of the patients neither CGRP nor CGRP(-R) mAbs demonstrated a clinical meaningful effect. This is less than previously reported for single CGRP(-R)-mAbs [3,4,5,6,7,8] and may be due to the fact that a certain proportion of NR to a single CGRP(R)-mAb respond to the change of mAb class. A recent German multicenter study showed that one-third of NR to the CGRP(-R)-mAb erenumab responded well when switched to a CGRP(-R)-mAb [39].

Previous studies revealed that the number of MHD correlates inversely with the likelihood of a positive treatment response to CGRP(-R) mAb [19, 32, 40,41,42]. In line with these observations, NR of the present study suffered significantly more often from CM and had a significantly higher frequency of MHD and MMD at baseline. Persistent activation of inflammatory signal pathways and neuronal sensitization play a key role in migraine progression and chronification, causing sustained neuronal hypersensitivity [43, 44]. While CGRP is one important mediator in the development of sensitization [45], several other neurotransmitters are involved, e.g. vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) [46, 47]. It is possible that in clinical NR to CGRP(-R) mAbs, CGRP has a negligible pathophysiological role and other molecular pathways prevail. In line with this hypothesis, one-third of migraine patients do not develop migraine following the intravenous administration of CGRP (“non-CGRP phenotype”) [33, 48].

Apart from these pathophysiological considerations, psychopathological conditions are thought to act as migraine worsening factors [18]. Depression is a frequent comorbidity of migraine, particularly CM [49] and is associated with higher headache frequency [50]. Consistent with the clinical profile of patients with refractory migraine and treatment failure in CGRP-mAb proposed by Silvestro et al. [51], in our cohort, NR suffered significantly more frequently from concomitant depression than SR. Presence of comorbid depression is not only associated with poor treatment response to CGRP-mAb therapy, but was also shown to be a negative predictor of good treatment response to Onabotulinumtoxin A [52, 53]. In light of its negative association to prophylactic treatment response, more attention should be drawn to concomitant depression in migraine focusing on the evaluation of potential need for psychotherapeutic or pharmacotherapeutic treatment. Selected patient may benefit from combination therapy of antidepressants and CGRP-mAb and multimodal treatment concepts should be strived for in this burdened patient group.

Another frequent comorbidity in NR was MOH. Medication overuse is associated with poor response to acute medications [54], contributes the process to chronicity as well as treatment refractivity of migraine [55], and is therefore considered to be a prognostic factor for poor response to preventive treatment [26, 45]. Our results are in line with previous findings of Silvestro et al [51] and Ornello et al [56] who demonstrated greater medication overuse in patients with therapy resistant migraine to CGRP(-R) mAb therapy. However, several studies have demonstrated efficacy of CGRP(-R) mAb in MO with a remission von MO to non-MO [57]. Therefore, MO alone may not be the determining factor for the lack of response to therapy, but rather a combination of different clinical features and comorbidities. In patients with MOH and inadequate response to CGRP(-R) mAbs, withdrawal can be attempted, as central sensitization can successfully improve after detoxification [58] and studies suggest better response to preventive treatment after withdrawal [57].

Evidence-based recommendations regarding CGRP(-R) mAb non-response after multiple other preventatives are lacking [59]. Even though both classes of CGRP(-R) mAb had already been tested unsuccessfully, the most frequent change in our group of NR was to the third and last available CGRP-mAb. The reason behind this clinical decision may be the slightly different pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of galcanezumab and fremanezumab [2] but, above all, the lack of alternatives in patients who had already tried all treatments of first choice unsuccessfully. Presumably in the absence of alternatives, a non-negligible proportion of NR also switched back to oral prophylactics or Onabotulinumtoxin A, although these had not shown sufficient efficacy previously. The evaluation of these treatment strategies was not the subject of this investigation and should be assessed in future studies with a larger sample size.

Our study was designed as a retrospective analysis of data from our headache outpatient clinic, so no causal relationships can be drawn. Our aim was to describe the characteristics of the two groups of SR and NR in an initially exploratory approach. In the next step, a longitudinal study to verify those results would be necessary. The rigorously chosen criteria for SR and NR allow us to describe characteristics that apply for these two specific groups of patients. However, the strict inclusion criteria result in a limited sample size for the groups of interest. Some of the described trends could possibly reach statistical significance if the groups were larger. Future multicenter studies should provide for larger cohort to ensure a higher statistical power. Further limitations include some missing data of headache characteristics, which can cause bias in the estimation of results.

Conclusion

The presence of chronic migraine, high headache frequency at baseline, medication overuse, concomitant depression, and subjective poor response to acute therapy with triptans are typical features of non-responders to CGRP-targeted treatment. Conversely, a lower headache frequency prior to treatment begin, good response to triptans and pronounced vegetative symptoms such as vomiting occur more often in super-responders. This work is in line with the existing evidence on treatment response in patients treated with CGRP(-R) mAbs but expands into a highly treatment-resistant cohort. An accurate clinical evaluation before starting treatment with CGRP(-R) mAbs might help to achieve a more tailored therapeutic management in patients with migraine.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CM:

-

Chronic migraine

- CGRP:

-

Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide

- CGRP-R:

-

Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide-receptor

- EM:

-

Episodic migraine

- ICHD-3:

-

International Classification of Headache Disorders 3

- mAb:

-

Monoclonal antibody

- MHD:

-

Monthly headache days

- MD:

-

Missing data

- MMD:

-

Monthly migraine days

- MOH:

-

Medication overuse headache

- NMD:

-

Non-migraine days

- NR:

-

Non-responder

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SR:

-

Super-responder

References

Edvinsson L, Haanes KA, Warfvinge K, Krause DN (2018) CGRP as the target of new migraine therapies - successful translation from bench to clinic. Nat Rev Neurol 14:338–350. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-018-0003-1

Raffaelli B, Neeb L, Reuter U (2019) Monoclonal antibodies for the prevention of migraine. Expert Opin Biol Ther 19:1307–1317. https://doi.org/10.1080/14712598.2019.1671350

Goadsby PJ, Reuter U, Hallström Y, Broessner G, Bonner JH, Zhang F, Sapra S, Picard H, Mikol DD, Lenz RA (2017) A controlled trial of erenumab for episodic migraine. N Engl J Med 377:2123–2132. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1705848

Dodick DW, Ashina M, Brandes JL, Kudrow D, Lanteri-Minet M, Osipova V, Palmer K, Picard H, Mikol DD, Lenz RA (2018) ARISE: a phase 3 randomized trial of erenumab for episodic migraine. Cephalalgia 38:1026–1037. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102418759786

Tepper S, Ashina M, Reuter U, Brandes JL, Doležil D, Silberstein S, Winner P, Leonardi D, Mikol D, Lenz R (2017) Safety and efficacy of erenumab for preventive treatment of chronic migraine: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. The Lancet Neurology 16:425–434. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30083-2

Skljarevski V, Oakes TM, Zhang Q, Ferguson MB, Martinez J, Camporeale A, Johnson KW, Shan Q, Carter J, Schacht A et al (2018) Effect of different doses of galcanezumab vs placebo for episodic migraine prevention: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol 75:187–193. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.3859

Stauffer VL, Dodick DW, Zhang Q, Carter JN, Ailani J, Conley RR (2018) Evaluation of galcanezumab for the prevention of episodic migraine: the EVOLVE-1 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol 75:1080–1088. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.1212

Dodick DW, Silberstein SD, Bigal ME, Yeung PP, Goadsby PJ, Blankenbiller T, Grozinski-Wolff M, Yang R, Ma Y, Aycardi E (2018) Effect of fremanezumab compared with placebo for prevention of episodic migraine: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 319:1999–2008. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.4853

Silberstein SD, Dodick DW, Bigal ME, Yeung PP, Goadsby PJ, Blankenbiller T, Grozinski-Wolff M, Yang R, Ma Y, Aycardi E (2017) Fremanezumab for the preventive treatment of chronic migraine. N Engl J Med 377:2113–2122. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1709038

Detke HC, Goadsby PJ, Wang S, Friedman DI, Selzler KJ, Aurora SK (2018) Galcanezumab in chronic migraine: the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled REGAIN study. Neurology 91:e2211–e2221. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000006640

Reuter U, Goadsby PJ, Lanteri-Minet M, Wen S, Hours-Zesiger P, Ferrari MD, Klatt J (2018) Efficacy and tolerability of erenumab in patients with episodic migraine in whom two-to-four previous preventive treatments were unsuccessful: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3b study. Lancet 392:2280–2287. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32534-0

Ferrari MD, Diener HC, Ning X, Galic M, Cohen JM, Yang R, Mueller M, Ahn AH, Schwartz YC, Grozinski-Wolff M et al (2019) Fremanezumab versus placebo for migraine prevention in patients with documented failure to up to four migraine preventive medication classes (FOCUS): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3b trial. Lancet 394:1030–1040. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31946-4

Mulleners WM, Kim B-K, Láinez MJA, Lanteri-Minet M, Pozo-Rosich P, Wang S, Tockhorn-Heidenreich A, Aurora SK, Nichols RM, Yunes-Medina L et al (2020) Safety and efficacy of galcanezumab in patients for whom previous migraine preventive medication from two to four categories had failed (CONQUER): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3b trial. Lancet Neurol 19:814–825. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30279-9

Broessner G, Reuter U, Bonner JH, Dodick DW, Hallström Y, Picard H, Zhang F, Lenz RA, Klatt J, Mikol DD (2020) The Spectrum of response to erenumab in patients with episodic migraine and subgroup analysis of patients achieving ≥50%, ≥75%, and 100% response. Headache 60:2026–2040. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.13929

Cullum CK, Do TP, Ashina M, Bendtsen L, Hugger SS, Iljazi A, Gusatovic J, Snellman J, Lopez-Lopez C, Ashina H et al (2022) Real-world long-term efficacy and safety of erenumab in adults with chronic migraine: a 52-week, single-center, prospective, observational study. J Headache Pain 23:61. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-022-01433-9

Vernieri F, Altamura C, Brunelli N, Costa CM, Aurilia C, Egeo G, Fofi L, Favoni V, Lovati C, Bertuzzo D et al (2022) Rapid response to galcanezumab and predictive factors in chronic migraine patients: a 3-month observational, longitudinal, cohort, multicenter, Italian real-life study. Eur J Neurol 29:1198–1208. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.15197

Barbanti P, Aurilia C, Egeo G, Fofi L, Cevoli S, Colombo B, Filippi M, Frediani F, Bono F, Grazzi L et al (2021) Erenumab in the prevention of high-frequency episodic and chronic migraine: Erenumab in Real Life in Italy (EARLY), the first Italian multicenter, prospective real-life study. Headache 61:363–372. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.14032

Barbanti P, Aurilia C, Cevoli S, Egeo G, Fofi L, Messina R, Salerno A, Torelli P, Albanese M, Carnevale A et al (2021) Long-term (48 weeks) effectiveness, safety, and tolerability of erenumab in the prevention of high-frequency episodic and chronic migraine in a real world: results of the EARLY 2 study. Headache 61:1351–1363. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.14194

Barbanti P, Egeo G, Aurilia C, Altamura C, d’Onofrio F, Finocchi C, Albanese M, Aguggia M, Rao R, Zucco M et al (2022) Predictors of response to anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies: a 24-week, multicenter, prospective study on 864 migraine patients. J Headache Pain 23:138. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-022-01498-6

Frattale I, Caponnetto V, Casalena A, Assetta M, Maddestra M, Marzoli F, Affaitati G, Giamberardino MA, Viola S, Gabriele A et al (2021) Association between response to triptans and response to erenumab: real-life data. J Headache Pain 22:1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-020-01213-3

Nowaczewska M, Straburzyński M, Waliszewska-Prosół M, Meder G, Janiak-Kiszka J, Kaźmierczak W (2022) Cerebral blood flow and other predictors of responsiveness to erenumab and fremanezumab in migraine-a real-life study. Front Neurol 13:895476. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2022.895476

Russo A, Silvestro M, Scotto di Clemente F, Trojsi F, Bisecco A, Bonavita S, Tessitore A, Tedeschi G (2020) Multidimensional assessment of the effects of erenumab in chronic migraine patients with previous unsuccessful preventive treatments: a comprehensive real-world experience. J Headache Pain 21:69. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-020-01143-0

Bottiroli S, De Icco R, Vaghi G, Pazzi S, Guaschino E, Allena M, Ghiotto N, Martinelli D, Tassorelli C, Sances G (2021) Psychological predictors of negative treatment outcome with erenumab in chronic migraine: data from an open label long-term prospective study. J Headache Pain 22:114. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-021-01333-4

Iannone LF, Fattori D, Benemei S, Chiarugi A, Geppetti P, De Cesaris F (2022) Long-term effectiveness of three anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies in resistant chronic migraine patients based on the MIDAS score. CNS Drugs 36:191–202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-021-00893-y

Zecca C, Cargnin S, Schankin C, Giannantoni NM, Viana M, Maraffi I, et al (2022) Clinic and genetic predictors in response to erenumab. Eur J Neurol 29(4):1209–17

Barbanti P, Egeo G, Aurilia C, d’Onofrio F, Albanese M, Cetta I, Di Fiore P, Zucco M, Filippi M, Bono F et al (2022) Fremanezumab in the prevention of high-frequency episodic and chronic migraine: a 12-week, multicenter, real-life, cohort study (the FRIEND study). J Headache Pain 23:46. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-022-01396-x

Nutzenbewertungsverfahren zum Wirkstoff Erenumab (Migräne-Prophylaxe) - Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss https://www.g-ba.de/bewertungsverfahren/nutzenbewertung/411/#beschluesse.

Nutzenbewertungsverfahren zum Wirkstoff Galcanezumab (Migräne-Prophylaxe) - Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss https://www.g-ba.de/bewertungsverfahren/nutzenbewertung/450/#beschluesse.

Nutzenbewertungsverfahren zum Wirkstoff Fremanezumab (Migräne-Prophylaxe) - Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss in response to erenumab. Eur J Neurol 29:1209–1217. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.15236 (https://www.g-ba.de/bewertungsverfahren/nutzenbewertung/462/#beschluesse.predictors)

Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018;38:1–211. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102417738202.

Sacco S, Braschinsky M, Ducros A, Lampl C, Little P, van den Brink AM, Pozo-Rosich P, Reuter U, de la Torre ER, Sanchez Del Rio M et al (2020) European headache federation consensus on the definition of resistant and refractory migraine: developed with the endorsement of the European Migraine & Headache Alliance (EMHA). J Headache Pain 21:76. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-020-01130-5

Baraldi C, Castro FL, Cainazzo MM, Pani L, Guerzoni S (2021) Predictors of response to erenumab after 12 months of treatment. Brain Behav 11:e2260. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.2260

Christensen CE, Younis S, Deen M, Khan S, Ghanizada H, Ashina M (2018) Migraine induction with calcitonin gene-related peptide in patients from erenumab trials. J Headache Pain 19:105. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-018-0927-2

Benemei S, Cortese F, Labastida-Ramírez A, Marchese F, Pellesi L, Romoli M, Vollesen AL, Lampl C, Ashina M, School of Advanced Studies of the European Headache Federation (EHF-SAS) (2017) Triptans and CGRP blockade - impact on the cranial vasculature. J Headache Pain 18:103. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-017-0811-5

Kageneck C, Nixdorf-Bergweiler BE, Messlinger K, Fischer MJ (2014) Release of CGRP from mouse brainstem slices indicates central inhibitory effect of triptans and kynurenate. J Headache Pain 15:7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1129-2377-15-7

Mason BN, Wattiez A-S, Balcziak LK, Kuburas A, Kutschke WJ, Russo AF (2020) Vascular actions of peripheral CGRP in migraine-like photophobia in mice. Cephalalgia 40:1585–1604. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102420949173

Ailani J, Kaiser EA, Mathew PG, McAllister P, Russo AF, Vélez C, Ramajo AP, Abdrabboh A, Xu C, Rasmussen S et al (2022) Role of calcitonin gene-related peptide on the gastrointestinal symptoms of migraine-clinical considerations: a narrative review. Neurology. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000201332.10.1212/WNL.0000000000201332

Salem-Abdou H, Simonyan D, Puymirat J (2021) Identification of predictors of response to erenumab in a cohort of patients with migraine. Cephalalgia Reports 4:25158163211026650. https://doi.org/10.1177/25158163211026646

Overeem LH, Peikert A, Hofacker MD, Kamm K, Ruscheweyh R, Gendolla A, Raffaelli B, Reuter U, Neeb L (2022) Effect of antibody switch in non-responders to a CGRP receptor antibody treatment in migraine: a multi-center retrospective cohort study. Cephalalgia 42:291–301. https://doi.org/10.1177/03331024211048765

Alpuente A, Gallardo VJ, Asskour L, Caronna E, Torres-Ferrus M, Pozo-Rosich P (2022) Salivary CGRP and erenumab treatment response: towards precision medicine in migraine. Ann Neurol 92:846–859. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.26472

Schoenen J, Timmermans G, Nonis R, Manise M, Fumal A, Gérard P (2021) Erenumab for migraine prevention in a 1-year compassionate use program: efficacy, tolerability, and differences between clinical phenotypes. Front Neurol 12:805334. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2021.805334

Lowe M, Murray L, Tyagi A, Gorrie G, Miller S, Dani K, NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde Headache Service (2022) Efficacy of erenumab and factors predicting response after 3 months in treatment resistant chronic migraine: a clinical service evaluation. J Headache Pain 23:86. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-022-01456-2

Greco R, Demartini C, Francavilla M, Zanaboni AM, Tassorelli C (2022) Antagonism of CGRP receptor: central and peripheral mechanisms and mediators in an animal model of chronic migraine. Cells 11:3092. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11193092

Munro G, Petersen S, Jansen-Olesen I, Olesen J (2018) A unique inbred rat strain with sustained cephalic hypersensitivity as a model of chronic migraine-like pain. Sci Rep 8:1836. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-19901-1

Edvinsson L (2021) CGRP and migraine: from bench to bedside. Rev Neurol (Paris) 177:785–790. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurol.2021.06.003

Rustichelli C, Lo Castro F, Baraldi C, Ferrari A (2020) Targeting pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) with monoclonal antibodies in migraine prevention: a brief review. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 29:1269–1275. https://doi.org/10.1080/13543784.2020.1811966

Waschek JA, Baca SM, Akerman S (2018) PACAP and migraine headache: immunomodulation of neural circuits in autonomic ganglia and brain parenchyma. J Headache Pain 19:23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-018-0850-6

Ashina H, Schytz HW, Ashina M (2018) CGRP in human models of primary headaches. Cephalalgia 38:353–360. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102416684344

Buse DC, Manack A, Serrano D, Turkel C, Lipton RB (2010) Sociodemographic and comorbidity profiles of chronic migraine and episodic migraine sufferers. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 81:428–432. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.2009.192492

Ruscheweyh R, Müller M, Blum B, Straube A (2014) Correlation of headache frequency and psychosocial impairment in migraine: a cross-sectional study. Headache 54:861–871. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.12195

Silvestro M, Tessitore A, Scotto di Clemente F, Battista G, Tedeschi G, Russo A (2021) Additive interaction between Onabotulinumtoxin-A and erenumab in patients with refractory migraine. Front Neurol 12:656294. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2021.656294

Barad M, Sturgeon JA, Fish S, Dexter F, Mackey S, Flood PD (2019) Response to BotulinumtoxinA in a migraine cohort with multiple comorbidities and widespread pain. Reg Anesth Pain Med 44:660–668. https://doi.org/10.1136/rapm-2018-100196

Schiano di Cola F, Caratozzolo S, Liberini P, Rao R, Padovani A (2019) Response predictors in chronic migraine: medication overuse and depressive symptoms negatively impact onabotulinumtoxin-a treatment. Front Neurol 10:678. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2019.00678

Lipton RB, Munjal S, Buse DC, Fanning KM, Bennett A, Reed ML (2016) Predicting inadequate response to acute migraine medication: results from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) study. Headache 56:1635–1648. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.12941

May A, Schulte LH (2016) Chronic migraine: risk factors, mechanisms and treatment. Nat Rev Neurol 12:455–464. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2016.93

Ornello R, Casalena A, Frattale I, Gabriele A, Affaitati G, Giamberardino MA, Assetta M, Maddestra M, Marzoli F, Viola S et al (2020) Real-life data on the efficacy and safety of erenumab in the Abruzzo region, central Italy. J Headache Pain 21:32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-020-01102-9

Caronna E, Gallardo VJ, Alpuente A, Torres-Ferrus M, Pozo-Rosich P (2021) Anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies in chronic migraine with medication overuse: real-life effectiveness and predictors of response at 6 months. J Headache Pain 22:120. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-021-01328-1

De Icco R, Fiamingo G, Greco R, Bottiroli S, Demartini C, Zanaboni AM, Allena M, Guaschino E, Martinelli D, Putortì A et al (2020) Neurophysiological and biomolecular effects of erenumab in chronic migraine: an open label study. Cephalalgia 40:1336–1345. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102420942230

Sacco S, Amin FM, Ashina M, Bendtsen L, Deligianni CI, Gil-Gouveia R, Katsarava Z, MaassenVanDenBrink A, Martelletti P, Mitsikostas D-D et al (2022) European Headache Federation guideline on the use of monoclonal antibodies targeting the calcitonin gene related peptide pathway for migraine prevention - 2022 update. J Headache Pain 23:67. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-022-01431-x

Acknowledgements

BR is participant in the BIH Charité Clinician Scientist Program funded by the Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin and the Berlin Institute of Health at Charité (BIH).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BR, MF and UR designed the study. BR, MF, LHO, MT and ES contributed to data collection. BR and MF analyzed the data. BR, MF and UR interpreted the data. BR, MF and UR wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Charité Ethical Committee (EA1/159/22). Written informed consent was not required due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

R reports research grants from Novartis, and personal fees from Abbvie/Allergan, Hormosan, Lilly, Novartis, and Teva. MF reports personal feed from TEVA. MT reports personal fees from TEVA. UR received honoraria for consulting and lectures from Amgen, Allergan, Abbvie, Eli Lilly, Lundbeck, Novartis, electroCore, Medscape, StreaMedUp, and Teva. UR received research funding from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research and Novartis. The other authors have nothing to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Summary of current literature on predictors of good clinical response to treatment with CGRP(-R)-mAbs.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Raffaelli, B., Fitzek, M., Overeem, L.H. et al. Clinical evaluation of super-responders vs. non-responders to CGRP(-receptor) monoclonal antibodies: a real-world experience. J Headache Pain 24, 16 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-023-01552-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-023-01552-x