Abstract

Background

Migraine prevention with erenumab and migraine induction by calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) both carry notable individual variance. We wanted to explore a possible association between individual efficacy of anti-CGRP treatment and susceptibility to migraine induction by CGRP.

Methods

Thirteen migraine patients, previously enrolled in erenumab anti-CGRP receptor monoclonal antibody trials, received CGRP in a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized cross-over design to investigate their susceptibility to migraine induction. A standardized questionnaire was used to assess the efficacy of previous antibody treatment. The patients were stratified into groups of high responders and poor responders. Primary outcomes were incidence of migraine-like attacks and area under the curve of headache intensity after infusion of CGRP and placebo. All interviews and experiments were performed in laboratories at the Danish Headache Center, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Results

Ten high responders and three poor responders were included. CGRP induced migraine-like attacks in ten (77%) patients, whereof two were poor responders, compared to none after placebo (p = 0.002). The area under the curve for headache intensity was greater after CGRP, compared to placebo, at 0–90 min (p = 0.009), and 2–12 h (p = 0.014). The median peak headache intensity score was 5 (5–9) after CGRP, compared to 2 (0–4) after placebo (p = 0.004).

Conclusions

Patients with an excellent effect of erenumab are highly susceptible to CGRP provocation. If an association is evident, CGRP provocation could prove a biomarker for predicting antibody treatment efficacy.

Trial registration

Retrospectively registered at clinicaltrials.gov with identifier: NCT03481400.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Clinicians treating migraine have, until now, been limited to preventive drugs that were initially developed for cardiovascular, psychiatric or neurological diseases other than migraine. [1] Four anti calcitonin gene-related peptide (anti-CGRP) monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) are in late-phase development as the first class of preventive therapeutics targeting migraine-specific mechanisms. [2] Three mAbs (fremanezumab, eptinezumab and galcanezumab) are ligand specific, and bind to CGRP, while one (erenumab) binds to the receptor complex (Fig. 1). [3,4,5,6] Overall efficacy and tolerability between the four antibodies are quite similar, but individual efficacy is widespread. While some patients report excellent efficacy, 35% report less than 50% reduction in monthly migraine days when treated with erenumab. [7] The question is whether we can identify which patients to treat with the new therapeutics by predicting efficacy response and thereby introduce personalized treatment schemes.

Intracellular signaling pathways of calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor activation. One effect of CGRP receptor activation is adenylate cyclase-mediated cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) elevation, which leads to protein kinase A (PKA) activation, and activation of multiple targets depending on cell type. Nitric oxide synthesis may be the result of nitric oxide synthase (NOS) phosphorylation, gene transcription changes may be a result of cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) activation, and relaxation of vascular smooth muscle cells is partly a result of ATP-sensitive potassium channels (K+ channels) activation

Calcitonin gene-related peptide induces migraine-like attacks in an average of 62% of migraine patients across placebo-controlled and open-label provocation studies. [8,9,10,11] Individual differences in mAb efficacy and migraine induction suggest that CGRP involvement in migraine varies between patients, and susceptibility to provocation could be a possible biomarker for anti-CGRP treatment efficacy.

We sought to investigate a possible association between anti-CGRP treatment efficacy and susceptibility to CGRP-induced migraine-like attacks. Our hypotheses were that CGRP would conduce to a small migraine-like attack rate in a group of patients with little to no effect of erenumab and a large attack rate in a group who experienced an excellent effect of erenumab.

Methods

Recruitment process

Patients, who had participated in the episodic and chronic erenumab trials (ClincalTrials.gov IDs: NCT02483585 and NCT02066415), were recruited from the Danish Headache Center. These patients were contacted and enrolled after completing their participation in the mAb trial. Patients, who were likely eligible for participation in up-coming anti-CGRP mAbs clinical trials, were recruited from the Danish Headache Center as well. The patients were enrolled from July 25 2016 to June 21 2017. Inclusion criteria: migraine with and/or without aura according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-3 beta) [12], age 18 to 65 years, and previous/probable participation in an anti-CGRP mAb trial. Exclusion criteria: use of pharmacological agents (except contraceptives and preventive migraine medication), cardiovascular disease and other serious somatic or psychiatric disorders.

Study design

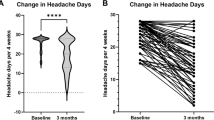

Response to anti-CGRP mAb treatment was evaluated using a standardized questionnaire (Fig. 2). Patients rated treatment efficacy for reduction in: migraine days, headache days, days using rescue medication, and headache intensity. Treatment efficacy was assessed based on the patients’ last month of receiving mAbs. Patients, who reported an excellent effect of treatment (efficacy score ≥ 50%) in at least two of the four outcome variables, were defined as high responders. The remaining patients were defined as poor responders.

Patients received 1.5 μg/min human α-CGRP (PolyPeptide, Strasbourg, France) and placebo isotonic saline as infusions over 20 min on two separate study days in a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized, cross-over design.

Experimental protocol

Patients reported to the clinic headache-free for at least 48 h. Coffee, tea, cocoa, cola, tobacco, and alcohol were not allowed for 12 h before study start. Patients were instructed to fast for four hours before study start. Fertile female participants underwent a pregnancy test upon arrival at the hospital.

Patients underwent a medical examination on the first study day. A venous catheter was inserted into a cubital vein, followed by rest in supine position for 30 min, before initiating the infusion. Intensity and characteristics of headache, heart rate (HR), blood pressure, and adverse events were registered every 10 min from 10 min before to 90 min after infusion.

Headache intensity and characteristics

Headache intensity was rated based on a 0 to 10 numeric rating scale (NRS) where ‘0’ denoted no headache, and ‘10’ the worst possible headache.

Headache characteristics were recorded using a standardized questionnaire including headache intensity, location, quality, aggravation by physical activity, and accompanying symptoms.

Upon discharge from the hospital, patients were instructed to self-report headache intensity and characteristics in a standardized headache diary hourly from 2 to 12 h after infusion start. Patients were allowed to use their usual migraine medication after discharge.

Migraine-like attack criteria

Pharmacologically-induced migraine attacks are not spontaneous attacks, and cannot fulfill the ICHD-3 beta criteria. [12] Therefore, modified criteria for experimentally-induced attacks were developed based on the following considerations. [13, 14] Firstly, the majority of patients report that the induced attacks mimic their spontaneous attacks. [10, 15] Secondly, spontaneous migraine attacks mostly develop in a matter of hours, and in the beginning of the attack phenomenologically fulfill the criteria for tension-type headache. Only hereafter, the headache worsens, becomes unilateral and presents the associated symptoms required for a migraine diagnosis. Finally, most patients can predict an impending migraine attack in the early attack stage and cannot be denied treatment in an experimental setting. Thus, induced attacks are frequently treated before all migraine criteria are fulfilled. Accordingly, we used the following two criteria to define a pharmacologically-induced migraine-like attack [14]:

The headache fulfills criteria C and D of the ICHD-3 beta [12].

-

C: Headache has at least two of the following characteristics: Unilateral location, pulsating quality, moderate to severe intensity, or aggravation by physical activity.

-

D: At least one of the following accompanying symptoms: Nausea and/or vomiting, or photophobia and phonophobia.

or

Headache described as mimicking the patient’s spontaneous attack and treated with acute migraine rescue medication.

Statistical analysis

Headache intensity scores are presented as median (range). Heart rate and mean arterial pressure (MAP) are presented as mean ± standard deviation under the assumption that they adhere to a normal distribution. Primary endpoints were incidence of migraine-like attacks from 0 to 12 h after infusion and area under the curve (AUC), using the trapezoidal rule [16], for headache intensity score at 0 to 90 min and 90 min to 12 h on the CGRP day, as compared to the placebo day for all patients. McNemar’s test and Wilcoxon signed-rank test were used as appropriate. Secondary endpoints were HR and MAP, which were compared between the two study days using paired t-tests. Peak headache intensity score and time to peak headache were compared between the study days using Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Adverse events are reported as incidences on the CGRP and placebo day and compared between days using McNemar’s test in explorative analysis. Predictive values, sensitivity and specificity were also calculated as post hoc analyses.

Separate meaningful inference statistics within each mAb response groups could not be performed due to small subgroup sample sizes. Data from patients without previous experience from the erenumab trials were excluded from the final analyses as this recruitment was limited by the competitive enrollment strategies of the anti-CGRP mAbs clinical trials. No statistical power calculation was conducted prior to the study as the sample size was based on the available data. R (Version 3.4.2) was used to conduct the statistical analyses. P values are reported as two-tailed with a 5% level of significance.

Results

Participants

Thirteen patients (12 women) completed the study (Fig. 3). Seven were enrolled from the episodic migraine erenumab trial (ClincalTrials.gov ID: NCT02483585), and six were enrolled from the chronic migraine erenumab trial (ClincalTrials.gov ID: NCT02066415). All 13 patients were enrolled after completing the safety follow-up visit 12 weeks after the last dose of erenumab. Mean age was 39 years (standard deviation ±11 and range 22 to 53).

Inclusion flowchart. Twenty-three patients were enrolled in the study. Ten of these were excluded subsequently. One patient was excluded due to a cardiac conduction disease and one due to diabetes mellitus (well-regulated), according to the conventional CGRP provocation protocol. Three patients were excluded from analysis as they did not participate in the erenumab trials. One patient withdrew consent before the experiments. Four patients were lost to follow-up and one of these had participated in the first study day. Data from these days were excluded from analyses. Of the ten patients, who were excluded, seven had received erenumab and six of these were high responders. Response status was not obtained from the last of the seven subjects

Clinical characteristics, migraine incidence and intensity

Headache characteristics and accompanying symptoms are presented in Table 1. Ten of 13 patients (77%) developed migraine-like attacks after CGRP, compared to none after placebo (p = 0.002) (Fig. 4). Two of the 10 patients, who experienced migraine-like attacks, reported poor response to treatment (patients 5 and 12).

The three patients, who did not develop migraine-like attacks after CGRP, were chronic migraine patients (patients 9, 10 and 11). One of these patients (patient 11) was a poor responder with an efficacy score of zero for all four outcome variables. The other two patients were high responders (patients 9 and 10).

The AUC for headache intensity was greater after CGRP compared to placebo at both 0 to 90 min (p = 0.009) and 2 to 12 h (p = 0.014) (Fig. 5). The median peak headache intensity score was 5 (5 to 9) after CGRP, compared to 2 (0 to 4) after placebo (p = 0.004). Time to peak headache was 180 min (110 to 270) after CGRP and 330 min (72.5 to 660) after placebo (p = 0.250).

Headache intensity after CGRP and placebo. Individual headache intensity scores on the CGRP day (a) and placebo day (b). Black lines: Median intensity at each time point. The median headache intensity was 0 for all time points after placebo. The median time (range) to onset of migraine was 50 min (20–152.5) after CGRP

Vital signs and adverse events

The AUC for HR was higher (p < 0.001) and AUC for MAP was lower (p < 0.001) after CGRP compared to placebo. All patients reported warm sensations (13/13 (100%)) after CGRP compared to only one patient reporting warm sensation (1/13, (8%)) after placebo (p < 0.001). Flushing was observed after CGRP in all patients (13/13 (100%)) compared to none after placebo (p < 0.001). Five of 13 patients (63%) reported palpitations after CGRP, compared to two of 13 (15%) after placebo (p = 0.014).

Predictive values, sensitivity and specificity

Positive predictive value for CGRP-induced attacks in erenumab high responders was 0.80 (95% CI 0.49 to 0.96) and sensitivity was 0.80 (95% CI 0.66 to 0.89). Negative predictive value was 0.33 (95% CI 0.08 to 0.73) and specificity was 0.33 (95% CI 0.01 to 0.91).

Discussion

Our major finding was that patients with response to erenumab showed hypersensitivity to CGRP infusion in a placebo-controlled experiment. In addition to a high migraine induction rate (77%), compared to previous studies, participants also reported moderate to severe (median peak intensity of 5, range 5 to 9) and long-lasting headaches (Fig. 5), which further points toward high CGRP susceptibility. Previous studies reported median peak headache intensities ranging from 1 to 4. [9, 10]

Mechanisms of migraine initiation by CGRP and migraine prevention by anti-CGRP mAbs are unknown. Calcitonin gene-related peptide is expressed in the trigeminal C fibers [17], trigeminal ganglion [18] and trigeminal nucleus caudalis [19], and its receptors are expressed in vascular smooth muscle cells [20], A-delta fibers [17] and trigeminal ganglia. [18] Calcitonin gene-related peptide binds to its receptor and activates multiple intracellular signaling pathways of which the most well-known is activation of adenylate cyclase and formation of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP). [21] In arteries, this leads to dilation through an endothelial-dependent synthesis of nitric oxide or relaxation of vascular smooth muscle cells via opening of ATP-sensitive potassium channels (Fig. 1). [22, 23] In trigeminal ganglion cells, the cAMP increase may cause sensitization of nociceptive neurons through upregulation of gene transcription and algogenic receptors in the cell membranes. [21, 24] In healthy volunteers, CGRP modulates inputs from noxious heat stimulation of the trigeminal area in the brain stem and insula. [25] The phosphodiesterase-3 inhibitor, cilostazol, potentiates the accumulation of cAMP in a receptor independent manner, and induces migraine in 86% of patients [26, 27], supporting the notion that cAMP upregulation may induce migraine. To what extent erenumab interacts with these mechanisms and exerts its anti-migraine effect is not fully clarified. Interestingly, erenumab inhibits CGRP-driven increases in dermal blood flow after capsaicin injections suggesting peripheral effects of CGRP receptor blockage. [28]

Our study explored a possible association between self-reported erenumab efficacy and sensitivity to migraine induction by CGRP. Identifying a link between poor response to mAb treatment and not developing migraine when challenged with CGRP (a so-called non-CGRP phenotype) could provide a biomarker for treatment response. In an effort to provide test reliability measures, we calculated predictive values, sensitivity and specificity as post hoc analyses. Positive predictive value and sensitivity for CGRP-induced attacks in erenumab high responders were high. In contrast, negative predictive value and specificity were low, impaired by the small sample of erenumab poor responders. We evaluated erenumab treatment response using four variables: reduction in migraine days, reduction in headache intensity, reduction in headache days and reduction in days using rescue medication. Our predefined criteria for “poor response” identified three such participants (subjects 5, 11 and 12 in Table 1). One of these was a non-responder who scored zero in all four efficacy variables. This participant reported no migraine after CGRP infusion. The other two poor responders reported migraine-like attacks after CGRP. We obtained treatment efficacy from 19 patients (Fig. 3) and only the three above-mentioned patients reported “poor response”. Therefore, we could not include enough poor responders to calculate a correlation to low migraine induction, which is a limitation. Furthermore, we cannot ignore the fact that having a poor response to erenumab in mAb trials might affect a patient’s willingness to participate in our study, subsequently leading to sampling bias. Our findings suggest that having a positive response to erenumab, based on our questionnaire variables, is associated with a high susceptibility to migraine induction by CGRP. The lack of a larger group of poor responders inhibits us from drawing conclusions on a possible association between those patients and a low susceptibility to CGRP. The question remains whether a CGRP provocation model can be used to predict efficacy of anti-CGRP mAb treatment when it becomes available. A large-scale prospective provocation study in patients, before they receive anti-CGRP treatment, would allow us to draw conclusions on poor responders i.e. patients with a possible non-CGRP migraine phenotype. When a sufficient number of non-responders have been provoked, we will be able to determine if the CGRP model of migraine is a biomarker for treatment response. Consequently, we will be able to provide biomarker reliability tests with sensitivity and specificity as outcome measures.

Conclusion

In this study we showed high migraine induction capabilities with CGRP in migraine patients who responded to erenumab treatment compared to data from previous CGRP provocation experiments. [8,9,10,11] If an association between poor migraine induction and poor treatment efficacy is also evident, the CGRP model of migraine could become the basis for a biomarker for mAb treatment response. Such a biomarker would be a powerful tool for clinicians choosing therapeutics for the prevention of migraine.

Abbreviations

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- cAMP:

-

Cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- CGRP:

-

Calcitonin gene-related peptide

- HR:

-

Heart rate

- ICHD-3 beta:

-

International classification of headache disorders version 3 beta

- mAb:

-

Monoclonal antibody

- MAP:

-

Mean arterial pressure

- NRS:

-

Numerical rating scale

References

Evers S, Áfra J, Frese A, Goadsby PJ, Linde M, May A et al (2009) EFNS guideline on the drug treatment of migraine - revised report of an EFNS task force. Eur J Neurol 16:968–981

Khan S, Olesen A, Ashina M. CGRP, a target for preventive therapy in migraine and cluster headache: systematic review of clinical data. Cephalalgia. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102417741297

Bigal ME, Dodick DW, Rapoport AM, Silberstein SD, Ma Y, Yang R et al (2015) Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of TEV-48125 for preventive treatment of high-frequency episodic migraine: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2b study. Lancet Neurol 14:1081–1090

Dodick DW, Goadsby PJ, Spierings ELH, Scherer JC, Sweeney SP, Grayzel DS (2014) Safety and efficacy of LY2951742, a monoclonal antibody to calcitonin gene-related peptide, for the prevention of migraine: a phase 2, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Lancet Neurol 13:885–892

Dodick DW, Goadsby PJ, Silberstein SD, Lipton RB, Olesen J, Ashina M et al (2014) Safety and efficacy of ALD403, an antibody to calcitonin gene-related peptide, for the prevention of frequent episodic migraine: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, exploratory phase 2 trial. Lancet Neurol 13:1100–1107

Sun H, Dodick DW, Silberstein S, Goadsby PJ, Reuter U, Ashina M et al (2016) Safety and efficacy of AMG 334 for prevention of episodic migraine: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Neurol 15:382–390

Ashina M, Dodick D, Goadsby PJ, Reuter U, Silberstein S, Zhang F et al (2017) Erenumab (AMG 334) in episodic migraine: interim analysis of an ongoing open-label study. Neurology 89:1237–1243

Guo S, Vollesen ALH, Olesen J, Ashina M (2016) Premonitory and nonheadache symptoms induced by CGRP and PACAP38 in patients with migraine. Pain 157:2773–2781

Hansen JM, Hauge AW, Olesen J, Ashina M (2010) Calcitonin gene-related peptide triggers migraine-like attacks in patients with migraine with aura. Cephalalgia 30:1179–1186

Lassen LH, Haderslev PA, Jacobsen VB, Iversen HK, Sperling B, Olesen J (2002) CGRP may play a causative role in migraine. Cephalalgia 22:54–61

Asghar MS, Hansen AE, Amin FM, van der Geest RJ, Koning P, Der V, HBW L et al (2011) Evidence for a vascular factor in migraine. Ann Neurol 69:635–645

Society HCC of the IH (2013) The international classification of headache disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia 33:629–808

Guo S, Christensen AF, Liu ML, Janjooa BN, Olesen J, Ashina M (2017) Calcitonin gene-related peptide induced migraine attacks in patients with and without familial aggregation of migraine. Cephalalgia 37:114–124

Schytz HW, Birk S, Wienecke T, Kruuse C, Olesen J, Ashina M et al (2009) PACAP38 induces migraine-like attacks in patients with migraine without aura. Brain 132:16–25

Olesen J, Thomsen LL, Iversen H (1994) Nitric oxide is a key molecule in migraine and other vascular headaches. Trends Pharmacol Sci 15:149–153

Matthews JN, Altman DG, Campbell MJ, Royston P (1990) Analysis of serial measurements in medical research. BMJ 300:230–235

Eftekhari S, Warfvinge K, Blixt FW, Edvinsson L (2013) Differentiation of nerve fibers storing CGRP and CGRP receptors in the peripheral Trigeminovascular system. J Pain 14:1289–1303

Eftekhari S, Salvatore CA, Calamari A, Kane SA, Tajti J, Edvinsson L (2010) Differential distribution of calcitonin gene-related peptide and its receptor components in the human trigeminal ganglion. Neuroscience 169:683–696

Eftekhari S, Edvinsson L (2011) Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and its receptor components in human and rat spinal trigeminal nucleus and spinal cord at C1-level. BMC Neurosci 12:112

Jansen-Olesen I, Jørgensen L, Engel U, Edvinsson L (2003) In-depth characterization of CGRP receptors in human intracranial arteries. Eur J Pharmacol 481:207–216

Russell FA, King R, Smillie S-J, Kodji X, Brain SD (2014) Calcitonin gene-related peptide: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev 94:1099–1142

Brain SD, Grant AD (2004) Vascular actions of calcitonin gene-related peptide and Adrenomedullin. Physiol Rev 84:903–934

Nelson MT, Huang Y, Brayden JE, Hescheler J, Standen NB (1990) Arterial dilations in response to calcitonin gene-related peptide involve activation of K+ channels. Nature 344:770–773

Fabbretti E, D’Arco M, Fabbro A, Simonetti M, Nistri A, Giniatullin R (2006) Delayed upregulation of ATP P2X3 receptors of trigeminal sensory neurons by calcitonin gene-related peptide. J Neurosci 26:6163–6171

Asghar MS, Becerra L, Larsson HBW, Borsook D, Ashina M (2016) Calcitonin gene-related peptide modulates heat nociception in the human brain - an fMRI study in healthy volunteers. PLoS One 11:1–20

Guo S, Olesen J, Ashina M (2014) Phosphodiesterase 3 inhibitor cilostazol induces migraine-like attacks via cyclic AMP increase. Brain 137:2951–2959

Khan S, Deen M, Hougaard A, Amin FM, Ashina M (2018) Reproducibility of migraine-like attacks induced by phosphodiesterase-3-inhibitor cilostazol. Cephalalgia 38:892–903

Vu T, Ma P, Chen JS, de Hoon J, Van Hecken A, Yan L et al (2017) Pharmacokinetic-Pharmacodynamic relationship of Erenumab (AMG 334) and capsaicin-induced dermal blood flow in healthy and migraine subjects. Pharm Res 34:1784–1795

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully thank laboratory technicians Lene Elkjær and Winnie Grønning for their assistance with data extraction.

Funding

This study was supported by the Lundbeck Foundation (R155–2014-171 and R249–2017-1608) and the Research Foundation of Rigshospitalet (E-23327-02). The funding parties had no influence on study design, inclusion of participants, collection or interpretation of data.

Availability of data and materials

Anonymized data can be shared, until one year after publication, upon request to the corresponding author from qualified investigators for purposes of replicating procedures and results.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CC: study concept and design, acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting and revision of manuscript. SY: study concept and design, acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting and revision of manuscript. MD, SK and HG: study concept and design, critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content. MA: study concept and design, interpretation of data, critical revision of manuscript, and study initiation and supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All participants provided written consent to participate after receiving written and oral information in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964, with subsequent revisions. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Capital Region of Denmark (H-16014580). The study was registered retrospectively at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03481400).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

MA is a consultant or scientific advisor for Allergan, Amgen, Alder, Eli Lilly, Novartis and Teva, principal investigator for: Amgen 20120178 (Phase 2), 20120295 (Phase 2), 20130255 (Open label extension), 20120297 (Phase 3), 20150308 (Phase 2), ElectroCore GM-11 gamma-Core-R, TEVA TV48125-CNS-30068 (Phase 3), Novartis CAMG334A2301 (Phase 3) and Alder PROMISE-2. MA has no ownership interest and does not hold stock in any pharmaceutical company. MA serves as associated editor of Cephalalgia and co-editor of the Journal of Headache and Pain. SK has acted as invited speaker for Novartis. The remaining authors report no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Christensen, C.E., Younis, S., Deen, M. et al. Migraine induction with calcitonin gene-related peptide in patients from erenumab trials. J Headache Pain 19, 105 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-018-0927-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-018-0927-2