Abstract

Background

Migraine is now ranked as the second most disabling disorder worldwide reported by the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. As a noninvasive neurostimulation technique, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation(TENS) has been applied as an abortive and prophylactic treatment for migraine recently. We conduct this meta-analysis to analyze the effectiveness and safety of TENS on migraineurs.

Methods

We searched Medline (via PubMed), Embase, the Cochrane Library and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials to identify randomized controlled trials, which compared the effect of TENS with sham TENS on migraineurs. Data were extracted and methodological quality assessed independently by two reviewers. Change in the number of monthly headache days, responder rate, painkiller intake, adverse events and satisfaction were extracted as outcome.

Results

Four studies were included in the quantitative analysis with 161 migraine patients in real TENS group and 115 in sham TENS group. We found significant reduction of monthly headache days (SMD: -0.48; 95% CI: -0.73 to − 0.23; P < 0.001) and painkiller intake (SMD: -0.78; 95% CI: -1.14 to − 0.42; P < 0.001). Responder rate (RR: 4.05; 95% CI: 2.06 to 7.97; P < 0.001) and satisfaction (RR: 1.85; 95% CI: 1.31 to 2,61; P < 0.001) were significantly increased compared with sham TENS.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis suggests that TENS may serve as an effective and well-tolerated alternative for migraineurs. However, low quality of evidence prevents us from reaching definitive conclusions. Future well-designed RCTs are necessary to confirm and update the findings of this analysis.

Systematic review registration

Our PROSPERO protocol registration number: CRD42018085984. Registered 30 January 2018.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Migraine is now ranked as the second most disabling disorder worldwide reported by the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016 [1], which is characterized by recurrent moderate to severe unilateral throbbing head pain accompanied by photophobia, phonophobia, nausea and vomiting [2]. Therapeutic strategies are mainly based on both preventive and abortive drug therapy. However, conventional pharmacological therapies are partially effective and have unpleasant adverse effects inevitably. Overuse of symptomatic medication for headaches may lead to drug resistance and even transformation into refractory medication overuse headache [3]. Therefore, nonpharmacological therapeutic strategies with better efficacy and tolerance are pressingly needed.

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) is the delivery of pulsed low voltage electrical currents across the intact surface of the skin to stimulate peripheral nerves principally for pain relief [4]. As a noninvasive neurostimulation technique, TENS has gradually been the subject of extensive research in the treatment of headache disorders. Cefaly® is the first medical device approved by the FDA as a prophylactic treatment for episodic migraine, which stimulates the supratrochlear and supraorbital nerves [5]. Another novel non-invasive transcutaneous vagal nerve stimulation device, nVNS gammaCore, has been developed and is CE marked for acute and prophylactic treatment of primary headache disorders including cluster headache and migraine [6,7,8].

Although several clinical trials applying TENS as an abortive or prophylactic treatment for migraine have been carried out, there is no rigorous systematic review, to the best of our knowledge, investigating the effectiveness and safety of TENS in migraineurs. Therefore, the aim of this meta-analysis was to assess the evidence from randomized controlled clinical trials that used TENS for pain relief in migraine patients.

Methods

This meta-analysis was conducted according to the guidance of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis statement [9]. The review protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews and the registration number was CRD42018085984.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were identified based on the following criteria: (1) participants over 18 years old diagnosed with migraine according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-II or ICHD-III beta version); (2) comparing real TENS with sham TENS; (3) reporting migraine days, headache days, migraine attacks, pain intensity, painkiller intakes, adverse events or satisfaction as outcomes; (4) randomized controlled trials.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) comparison with other therapies such as drugs or psychotherapy; (2) applying invasive electrical nerve stimulation; (3) other types of trials such as cross-over designs, self-contrast trials and healthy controlled trials.

Literature search and study selection

Two reviewers (Tao and Wang) independently searched the following electronic databases up to December 2017: MEDLINE (via PubMed), Embase, the Cochrane Library and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials without language restrictions. The search strategies used can be found in Additional file 1. To avoid omitting relevant trials, conference abstracts and reference lists of all identified related publications were also searched. The computer search was supplemented with manual searches of the reference to expand potentially relevant articles. When multiple reports describing the same population were published, the most complete report was included.

Data extraction and outcome measures

Data extraction was performed independently by two authors. The following information was extracted from the included RCTs: first author; publication year; country; study design; sample size; study population (age range, gender split, baseline characteristics); intervention (stimulation site, parameters and duration of stimulation); adverse events and outcomes. We contacted to the corresponding authors when the related data were incomplete. Those who did not reply to our data request were excluded from the meta-analysis.

The primary outcomes included changes in monthly headache days between real and sham TENS, evaluated by headache diaries. Percentage of ‘responders’, i.e., of subjects having at least 50% reduction of monthly migraine days between the run-in period and the end of treatment was also investigated as primary outcome measures. Secondary outcomes were painkiller intake, satisfaction and adverse events during or after stimulation.

Assessment of risk of bias

Risk of bias assessment was performed independently by two authors (Tao and Wang) and adjudicated by a third investigator (Dong) in the event of disagreement, according to Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing bias in randomized trials [10]. The domains assessed were sequence generation (selection bias), allocation sequence concealment (selection bias), blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias), blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias), selective outcome reporting (reporting bias) and other potential sources of bias.

Data analysis

The data synthesis was performed by Review Manager 5.3 (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK). The standardized mean difference (SMD) and relative risk (RR) were used to compare continuous and dichotomous variables, respectively. All results were reported with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For studies that presented continuous data as means and range values, the standard deviations were calculated based on the principles of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [11].

Heterogeneity was tested using the chi-square test (P < 0.1) and quantified with the I2 statistic, which described the variation of effect size that was attributable to heterogeneity across studies [12]. I2 values smaller than 50% indicate no significant heterogeneity and are acceptable. The fixed-effect model of analysis is the appropriate. Otherwise, the random-effect model is considered.

Prespecified subgroup analysis was performed according to migraine attack frequency (episodic or chronic). Sensitivity analysis was also performed to determine effect size when low-quality studies were excluded. Owing to the limited number (n < 10) of included studies, publication bias was not assessed.

Finally, we assessed the quality of evidence by GRADE profiler, considering risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias [13].

Results

Study selection and inclusion

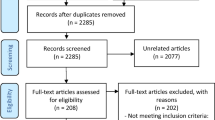

The flow chart for the selection process and detailed identification was presented in Fig. 1. Search strategies identified 368 potentially relevant publications. After the removal of duplicates, 294 articles were spotted, but only 22 remained after screening titles and abstracts. In the eligible articles, one trial enrolled both tension-type headache patients and migraineurs [14], and we were unable to extract data of migraineurs separately. We failed to contact the authors for the detail data until the end of this review. Ultimately, four RCTs, enrolling a total of 276 patients were included in the meta-analysis [15,16,17,18].

Study characteristics

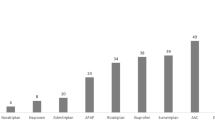

The characteristics of the studies included are summarized in Table 1. The four studies were published between 2013 and 2017 in English. Two of them were multicenter trials in Belgium [15] and the USA [16], the others were monocenter trials in China [17, 18]. Patients with at least 2 migraine attacks each month or chronic migraine were recruited in the trials. The four included studies ranged in size from 59 to 88 subjects and from 1 to 8 months in duration. Different TENS manufacturers applied pulsed electrical stimulation to supraorbital nerves (the branch of the trigeminal nerve), vagus nerves, occipital nerves and Taiyang (EX-HN 5) acupoints (trigeminal nerve indirectly) respectively. Parameters including frequency and amplitude were different among the trials in real TENS groups. In three studies [16,17,18], the sham group had the same device applied but received no electrical stimulation. In the one study [15], the intensity of sham simulation was far less than the real group. The outcome measurement methods were common across all studies, using headache diaries. One study had a high dropout rate [16] and all studies had an intention-to-treat analysis.

Risk of bias

Figure 2 summarized the risk of bias of four selected studies considering main outcomes. For the criteria sequence generation, we judged one trial as having an uncertain risk of bias [15], because it didn’t provide sufficient information about randomization. All studies reported allocation concealment, therefore, we judged these studies as having low bias. It was noteworthy that, although all the studies claimed to be double-blind trials, it is difficult for patients to achieve a true blindness. For the sham protocol, three studies delivered no stimulation to devices [16,17,18], thus establishing blinding of participants is difficult. Only in one study both stimulators buzzed identically during treatment [15], and thus it was not possible to distinguish a sham from a real stimulator without testing both devices in parallel. Therefore, we deemed it at low risk of bias and the other three studies at a high risk of bias with respect to blinding of participants. All four studies used the headache diary to evaluate pain control, hence, evaluators could not influence this outcome measure. Therefore, we consider the studies as low risk of with regard to detection bias. One study had high dropout rate and we judge it as having a high risk of bias in terms of incomplete outcome data [16]. All studies utilized intention-to-treat analyses. Reporting bias and other potential sources of bias were judged as low in all included studies.

Primary outcomes

Change in the number of monthly headache days

The outcome data was analyzed with a fixed-effect model, and the pooled estimate of the four included RCTs suggested that compared with placebo group in migraine patients, real TENS was found to significantly reduce the number of monthly headache days (SMD: -0.48; 95% CI: -0.73 to − 0.23; P < 0.001), with moderate heterogeneity among the studies (I2 = 40%) (Fig. 3). Sensitivity analysis showed that heterogeneity was most likely because of the study by Li et al. [18], without which the heterogeneity reduced to zero with little change to the summary estimate (Fig. 4). The heterogeneity might be caused by the intervention. In the trial by Li et al. [18], percutaneous electrical nerve stimulation therapy utilized acupuncture-like needle probes insertion into the soft tissues to stimulate trigeminal nerves instead of electrodes.

Responder rate

All four studies with a total of 276 patients reported the number of responders. Responder rate was significantly higher in real TENS group than in sham TENS group (32.9% and 7.8%; RR: 4.05; 95% CI: 2.06–7.97; P < 0.001) (Fig. 5). Furthermore, the meta-analysis result of the included trials found a low level of heterogeneity (I2 = 0). Thus, we did not perform sensitivity analysis.

Secondary outcomes

Painkiller intake

Only two studies included reported painkiller intake as an outcome [15, 18]. The pooled estimate of two included RCTs suggested that compared with sham TENS in migraine patients, real TENS yielded significantly decreased monthly painkiller intake (SMD: -0.78; 95% CI: -1.14 to − 0.42; P < 0.001), presented in Fig. 6.

Adverse events

All studies included mentioned adverse events or side effects related to TENS or sham TENS therapy during the trials. Only one study aimed to assess the feasibility, safety, and tolerability of TENS and reported adverse events in detail [16]. The tolerability profile of noninvasive vagus nerve stimulation (nVNS) was satisfactory and generally similar to that of sham treatment. Most adverse events were mild or moderate and transient. The most commonly reported adverse events were upper respiratory tract infections, facial pain and gastrointestinal symptoms. Two studies explicitly reported no adverse events associated with TENS treatment [15, 18]. In the other study [17], only one patient reported one adverse event in the 2 Hz group. It was a form of pinch pain and the uncomfortable feeling subsided when the intensity of the stimulation was reduced.

Satisfaction

Three studies reported the number of people satisfied with the TENS treatment [15,16,17]. Compared with sham TENS in migraine patients, real TENS yielded significant satisfaction rate. The pooled data of the 104 patients in these three studies showed significantly higher satisfaction rate in the real TENS group than the sham group (RR:1.85; 95% CI: 1.31 to 2.61; P < 0.001), with no heterogenicity (I2 = 0%) across the studies (Fig. 7).

GRADE analysis

The quality of evidence for outcomes evaluated in this review was assessed according to GRADE guidelines (Fig. 8) For the outcome of change in monthly headache days, the evidence quality was rated as low. We rated down one level for risk of bias. As samples size was smaller than optimal information size, the quality of evidence was downgraded once again for imprecision. The prevalence of small studies increases the risk of publication bias. There is a propensity for small negative studies not to reach full publication, and this might lead to an exaggerated estimate of effect [19]. We found that some of the trials were registered on clinicaltrials.gov, but the results were not updated in time. However, we did not downgrade for the publication bias as we had no direct evidence of this. For the outcome of responder rate, the evidence quality was rated as ‘low’ similar to change in monthly headache days.

Discussion

This meta-analysis of 4 RCTs including 276 patients provides evidence that TENS could be an effective and well-tolerated technique in increasing responder rate, reducing headache days and painkiller intake when compared with sham treatment. All the enrolled patients in the included studies didn’t use prophylaxis drugs during the treatment and for 1 month prior to the treatment, which reduced the interference of prophylaxis drugs to a certain degree. However, the quality of the evidence was judged as ‘low’ GRADE due to the methodological limitations of the included studies, and overall small study sizes. Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate.

This is the first meta-analysis, to the best of our knowledge, to investigate the effectiveness and safety of TENS for the treatment of migraine. This result is similar to a 2017 Cochrane review by Gibson et al. [20] and a 2015 Cochrane review by Johnson et al. [4], which were unable to makes definitive conclusions of TENS for acute and neuropathic pain largely because of inadequate sample sizes and unsuccessful blinding of treatment interventions in the included studies.

TENS induced analgesia is thought to be multifactorial and the ‘gate control theory’ is in fact the most conceivable view [21]. Neurostimulation may work by activating large fiber sensory afferents, which may secondarily inhibit nociceptive inputs from small fibers and elevate pain thresholds. Moreover, central descending pain inhibitory systems may be engaged as demonstrated by both animal studies and functional imaging studies [22]. GammaCore may reduce pain through restoration of brainstem monoaminergic neurotransmission [23], suppression of glutamate levels and cortical spreading depression [24, 25]. Cefaly may exert beneficial effects via normalization of orbitofrontal and rostral anterior cingulate cortices hypometabolism [26]. Occipital neurostimulation may active Aβ fibers of trigeminocervical complex in the neck in order to inhibit the pain transmission [17] and restore central descending pain modulatory tone at the same time [22]. Electrical stimulation to Taiyang acupoints, which indirectly stimulates the branch of the trigeminal nerve, improves the endogenous morphine like substance and serotonin in the central nervous system to relieve pain [27, 28]. Despite their unique mechanisms, all stimulated are peripheral nerves, and they have a common basic theory-- ‘gate control theory’. In the future, with the increase in the number of studies, subgroup analysis can be performed according to the type of stimulated nerves to reduce heterogeneity to some extent.

Maintaining blinding is a major methodological challenge in studying TENS. Various types of sham TENS have been proposed including units that are identical in appearance but just deliver an initial brief period of stimulation at the start and then faded out [29]. In some studies, sham stimulation parameters are set below levels needed for therapeutic or even no current is delivered in control group [16,17,18]. However, active stimulation elicits strong sensations and a true sham treatment that establishes robust blinding of participants is challenge [30].

TENS technique has been applied for both acute treatment of migraine [31, 32] and migraine prevention [15, 17]. Even though some single-arm trials demonstrate the effectiveness of TENS for migraine [8, 31,32,33,34,35], the reliability is downgraded considering the placebo effect. Given that sham TENS methodologies may be inherently flawed, further studies can focus on assessing TENS versus preventive anti-migraine drugs, botulinum neurotoxin, or other nonpharmacologic treatments like neurofeedback and transcranial magnetic stimulation. Assessing conventional therapy versus conventional therapy plus active TENS can also be taken into consideration.

Limitations

Several limitations should be taken into account. Firstly, our analysis was based on only four RCTs and all of them had a relatively small sample size (n < 100). One trial enrolled both tension-type headache patients and migraineurs, and we failed to contact the authors for the detail data until the review was completed. The included studies varied in the number of sessions, stimulation parameters and stimulated nerve types particularly, which increased the potential biases in the studies. Secondly, no subgroup analysis was performed based on the stimulated nerve types owing to the small number of studies included. Thirdly, since only two trials reported headache intensity as outcomes and they differed in measuring method, classified as mild, moderate, severe pain and visual analogue (VAS) scale respectively, thus we didn’t perform a pooled analysis. Finally, the follow-up period was generally short, so long-term outcomes of TENS remain to be proved.

Conclusions

This meta-analysis indicates that TENS may be effective in increasing responder rate, reducing headache days and painkiller intake, serving as a well-tolerated alternative for migraineurs. Nevertheless, despite our rigorous methodology, the inherent limitations of included studies make it impossible for us to draw definitive conclusions. Blinding of participants should be emphasized in future TENS trials to explore the efficacy of TENS as a sole or adjuvant therapy in patients with migraine, especially suffering from refractory migraine. TENS could be of help also in patients with (or at risk for) medication overuse and in fragile migraine populations, namely children, adolescents, pregnants and elderly. Future large-scale, well-designed RCTs with extensive follow-up are necessary to provide evidence-based efficacy data, optimize our knowledge concerning patient selection, stimulation parameters and update the findings of this analysis.

Clinical implications

This is the first meta-analysis investigating the effectiveness and safety of TENS for the treatment of migraine.

There is low quality evidence suggesting that TENS may be effective in increasing responder rate, reducing headache days and painkiller intake, serving as a well-tolerated alternative for migraineurs.

Future well-designed RCTs with extensive follow-up are necessary to provide evidence-based efficacy data, optimize our knowledge concerning patient selection and stimulation parameters.

Abbreviations

- AE:

-

Adverse event

- CG:

-

Control group

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- EG:

-

Experimental group

- ICHD:

-

the International classification of headache disorders

- ITT:

-

Intension-to-treat

- M-H:

-

Mantel-Haenszel

- TENS:

-

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation

References

GBD (2016) Disease, injury incidence, prevalence collaborators (2017) global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet 390(10100):1211–1259

Akerman S, Romero-Reyes M, Holland PR (2017) Current and novel insights into the neurophysiology of migraine and its implications for therapeutics. Pharmacol Ther 172:151–170

Kristoffersen ES, Lundqvist C (2014) Medication-overuse headache: epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment. Ther Adv Drug Saf 5(2):87–99

Johnson MI, Paley CA, Howe TE, Sluka KA (2015) Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for acute pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 6:CD006142. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006142.pub3

Peroutka SJ (2015) Clinical trials update 2014: year in review. Headache 55(1):149–157

Gaul C, Diener HC, Silver N, Magis D, Reuter U, Andersson A, Liebler EJ, Straube A, Group PS (2016) Non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation for PREVention and acute treatment of chronic cluster headache (PREVA): a randomised controlled study. Cephalalgia 36(6):534–546

Kinfe TM, Pintea B, Muhammad S, Zaremba S, Roeske S, Simon BJ, Vatter H (2015) Cervical non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation (nVNS) for preventive and acute treatment of episodic and chronic migraine and migraine-associated sleep disturbance: a prospective observational cohort study. J Headache Pain 16:101

Barbanti P, Grazzi L, Egeo G, Padovan AM, Liebler E, Bussone G (2015) Non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation for acute treatment of high-frequency and chronic migraine: an open-label study. J Headache Pain 16:61

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 339:b2535

Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Juni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, Savovic J, Schulz KF, Weeks L, Sterne JA, Cochrane Bias Methods G, Cochrane Statistical Methods G (2011) The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 343:d5928

Higgins J, Green S (2011) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 Wiley-Blackwell,2011:102–8

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG (2003) Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 327(7414):557–560

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, Schunemann HJ, Group GW (2008) GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 336(7650):924–926

Bono F, Salvino D, Mazza MR, Curcio M, Trimboli M, Vescio B, Quattrone A (2015) The influence of ictal cutaneous allodynia on the response to occipital transcutaneous electrical stimulation in chronic migraine and chronic tension-type headache: a randomized, sham-controlled study. Cephalalgia 35(5):389–398

Schoenen J, Vandersmissen B, Jeangette S, Herroelen L, Vandenheede M, Gerard P, Magis D (2013) Migraine prevention with a supraorbital transcutaneous stimulator: a randomized controlled trial. Neurology 80(8):697–704

Silberstein SD, Calhoun AH, Lipton RB, Grosberg BM, Cady RK, Dorlas S, Simmons KA, Mullin C, Liebler EJ, Goadsby PJ, Saper JR, Group ES (2016) Chronic migraine headache prevention with noninvasive vagus nerve stimulation: the EVENT study. Neurology 87(5):529–538

Liu Y, Dong Z, Wang R, Ao R, Han X, Tang W, Yu S (2017) Migraine prevention using different frequencies of transcutaneous occipital nerve stimulation: a randomized controlled trial. J Pain 18(8):1006–1015

Li H, Xu QR (2017) Effect of percutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for the treatment of migraine. Medicine (Baltimore) 96(39):e8108

Dechartres A, Trinquart L, Boutron I, Ravaud P (2013) Influence of trial sample size on treatment effect estimates: meta-epidemiological study. BMJ 346:f2304

Gibson W, Wand BM, O'Connell NE (2017) Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) for neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 9:CD011976. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011976.pub2

Treede RD (2016) Gain control mechanisms in the nociceptive system. Pain 157(6):1199–1204

Robbins MS, Lipton RB (2017) Transcutaneous and percutaneous Neurostimulation for headache disorders. Headache 57 Suppl 1:4–13

Yuan H, Silberstein SD (2016) Vagus nerve and Vagus nerve stimulation, a comprehensive review: part III. Headache 56(3):479–490

Oshinsky ML, Murphy AL, Hekierski H Jr, Cooper M, Simon BJ (2014) Noninvasive vagus nerve stimulation as treatment for trigeminal allodynia. Pain 155(5):1037–1042

Chen SP, Ay I, de Morais AL, Qin T, Zheng Y, Sadeghian H, Oka F, Simon B, Eikermann-Haerter K, Ayata C (2016) Vagus nerve stimulation inhibits cortical spreading depression. Pain 157(4):797–805

Magis D, D'Ostilio K, Thibaut A, De Pasqua V, Gerard P, Hustinx R, Laureys S, Schoenen J (2017) Cerebral metabolism before and after external trigeminal nerve stimulation in episodic migraine. Cephalalgia 37(9):881–891

Ahmed HE, White PF, Craig WF, Hamza MA, Ghoname ES, Gajraj NM (2000) Use of percutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (PENS) in the short-term management of headache. Headache 40(4):311–315

Heidland A, Fazeli G, Klassen A, Sebekova K, Hennemann H, Bahner U, Di Iorio B (2013) Neuromuscular electrostimulation techniques: historical aspects and current possibilities in treatment of pain and muscle waisting. Clin Nephrol 79(Suppl 1):S12–S23

Rakel B, Cooper N, Adams HJ, Messer BR, Law LAF, Dannen DR, Miller CA, Polehna AC, Ruggle RC, Vance CGT (2010) A new transient sham TENS device allows for investigator blinding while delivering a true placebo treatment. J Pain Official J Am Pain Soc 11(3):230

Sluka KA, Bjordal JM, Marchand S, Rakel BA (2013) What makes transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation work? Making sense of the mixed results in the clinical literature. Phys Ther 93(10):1397–1402

Chou DE, Gross GJ, Casadei CH, Yugrakh MS (2017) External trigeminal nerve stimulation for the acute treatment of migraine: open-label trial on safety and efficacy. Neuromodulation 20(7):678–683

Grazzi L, Egeo G, Liebler E, Padovan AM, Barbanti P (2017) Non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation (nVNS) as symptomatic treatment of migraine in young patients: a preliminary safety study. Neurol Sci 38(1):197–199

Russo A, Tessitore A, Conte F, Marcuccio L, Giordano A, Tedeschi G (2015) Transcutaneous supraorbital neurostimulation in "de novo" patients with migraine without aura: the first Italian experience. J Headache Pain 16:69

Straube A, Ellrich J, Eren O, Blum B, Ruscheweyh R (2015) Treatment of chronic migraine with transcutaneous stimulation of the auricular branch of the vagal nerve (auricular t-VNS): a randomized, monocentric clinical trial. J Headache Pain 16:543

Vikelis M, Dermitzakis EV, Spingos KC, Vasiliadis GG, Vlachos GS, Kararizou E (2017) Clinical experience with transcutaneous supraorbital nerve stimulation in patients with refractory migraine or with migraine and intolerance to topiramate: a prospective exploratory clinical study. BMC Neurol 17(1):97

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Shu Min Tao (Department of Medical Imaging, Affiliated Hospital of Nantong University, Nantong, Jiangsu 226001, China) for reviewing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All data are fully available without restriction.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concept and design: QW, HT. Acquisition of data: HT, TW. Analysis and interpretation of data: HT, TW, XD, QG. Drafting of the manuscript: HT, HX. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: QW, XD. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All authors have read and approved the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Search strategy. (DOCX 14 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Tao, H., Wang, T., Dong, X. et al. Effectiveness of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for the treatment of migraine: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Headache Pain 19, 42 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-018-0868-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-018-0868-9