Abstract

Cellulose is synthesized by organisms belonging to each biological kingdom, from bacteria to terrestrial plants, leading to its global-scale distribution. However, the structural properties of cellulose, such as its microfibril size, crystal form, cross-sectional shape, and uniplanar orientation, vary among species. This mini-review discusses the structural properties and diversity of cellulose. After describing historical developments in the structural analysis of cellulose, the technique of intracrystalline deuteration and rehydrogenation to understand structural diversity—particularly the localization of crystalline allomorphs in single microfibril—is discussed. Furthermore, the development of cellulose materials that maintain hierarchical structures of wood is introduced, and methods for producing functional materials are presented.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

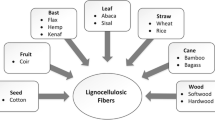

Cellulose is the most abundant organic material on Earth, with 1011–1012 tons produced each year, primarily from water and carbon dioxide by plant photosynthesis [1]; it has recently attracted considerable attention as a renewable material to replace fossil-based resources. Cellulose is a major component of wood, which is packed into crystalline fibers referred to as “microfibrils” that align to form oriented sheets. A lamellar structure, which is based on piled sheets, forms the cell wall, and cells arrange to form the anatomical structure of wood. The combination of this sophisticated hierarchical structure with matrix components such as hemicellulose and lignin provides trees with the mechanical properties that enable them to grow large in size and live for long periods of time.

Many organisms other than trees, including sea algae, ascidians, and bacteria such as Acetobacter, also synthesize cellulose; however, cellulose suprastructures (e.g., crystalline form, cross-sectional shape, and in-plane orientation) are highly diverse. This mini-review focuses on the structural diversity of natural cellulose and how historical developments have shaped our understanding of the cellulose structure. The intracrystalline deuteration technique that is used to evaluate structural diversity and methods for removing matrix components while maintaining the hierarchical structure of wood are also discussed in relation to their associated physical properties.

Crystalline allomorphs and their diversity

The Japanese researchers Nishikawa and Ono first identified the crystal formation of cellulose by irradiating wood, hemp, and bamboo with X-rays in 1913 to produce diffraction images [2]. Given that Laue had only recently discovered that X-rays produce diffraction patterns in 1912—by demonstrating that crystals are made up of periodic structures with intervals comparable to the wavelength of an X-ray—one can appreciate how both of these Japanese researchers made significant pioneering contributions to cellulose research. Subsequently, the active employment of X-ray diffractometry to obtain the first crystal model of cellulose was not reported until 1928 by Meyer and Mark [3], in which they proposed a parallel-chain structure with two molecular chains of the same orientation packed in a unit lattice. Since then, various unit lattices have been proposed, including the antiparallel chain model of Meyer and Misch in 1937 that involved two molecular chains face away from each other [4], and the eight-chain unit cell reported by Honjo and Watanabe two decades later [5]. Unfortunately, these models did not lead to the establishment of a widely accepted unified model.

The use of infrared (IR) spectroscopy, however, revealed that cellulose from sea algae and bacteria contain groups that differ from those of cotton and ramie, leading to the further classification of cellulose I as cellulose IA and IB [6, 7]. Fisher and Mann [8] examined the packing of molecular chains and found that the crystal lattices of cellulose IA and IB were different. Consequently, it remained a point of contention whether a unified model with the same structure for all natural celluloses or one with variations among species should be accepted. In 1974, a parallel-chain model was proposed using a combination of computerized refinement and energy calculations based on diffraction intensities, which was widely accepted as the crystal model for cellulose [9, 10]. However, it was not until the 1980s when solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy became available that a model corresponding to cellulose IA and IB was proposed, leading to a new phase of cellulose structural studies. In other words, the IA and IB natural classifications of cellulose I were abandoned in favor of a mixture of Iα and Iβ, the ratio of which varies among species [11, 12]. These two types of cellulose were broadly classified into the sea algae/bacteria type, in which Iα constitutes the majority, and the cotton/ramie type, which contains a large amount of Iβ. Moreover, Iα cellulose can be converted into Iβ by hydrothermal treatment [13] or high-temperature treatment in organic solvents and helium gas [14], which revealed that the Iβ phase is more physically stable.

In 1991, the electron diffraction patterns obtained from a single microfibril before (Iα-rich) and after (Iβ-dominant) hydrothermal treatment were analyzed, resulting in the proposed crystal models of single-chain triclinic and double-chain monoclinic unit cells corresponding to the Iα and Iβ forms [15]. The precise structures of native celluloses have since been determined by synchrotron X-ray and neutron diffractometry [16, 17]. The presence of Iα and Iβ can also be determined using IR spectroscopy [18], whereby cellulose Iα exhibits characteristic IR absorptions at 3240 and 750 cm−1, while Iβ exhibits bands at 3270 and 710 cm−1. Although it is not clear which cellulose crystal lattice is the dominant form in wood due to its low crystallinity, a multifaceted analysis relying on a combination of IR, NMR, X-ray, and electron diffraction techniques revealed that Iβ dominates both the poplar xylem wall and gelatin layer [19]. Ascidians are the only animal species that synthesize cellulose, predominantly as cellulose Iβ. Interestingly, it was discovered that the type of cellulose differed between ascidian larvae and adults, which synthesize Iα and Iβ, respectively [20]. Furthermore, separate synthetic genes were found to be involved, thus indicating that crystal structure formation is molecularly regulated in this animal. More recently, near-infrared spectroscopy [21] and terahertz time-domain spectroscopy [22] have been employed to evaluate cellulose structure in terms of its allomorphs.

Localization of cellulose allomorphs within a single microfibril

Table 1 summarizes the proposed microfibril domain distribution models. The micro-electron diffraction method was first suggested to model the localization of each allomorph along the fiber axis based on the diffraction pattern of a single cellulose microfibril that was continuously followed [15]. In addition, detailed analyses of electron diffraction data obtained from several species of green algae led to the conclusion that the Iα and Iβ domains are alternately/laterally localized in the microfibril direction [23].

An alternative model in which Iβ is distributed in the center of the microfibril crystal and Iα on the crystal surface (the “skin (Iα)-core (Iβ) structure”) was also proposed based on the concept that Iα, a metastable structure, is formed on the crystal surface under shear stress resulting from torsion associated with the bacterial cellulose ribbon [24]. Acid hydrolysis revealed microfibers with sharp tips rich in Iβ [25], suggesting that the Iα domains on the crystal surface are preferentially acid-hydrolyzed, leading to the skin (Iα)-core (Iβ) structure for green alga cellulose.

As was observed during acid hydrolysis, Iα is more susceptible to degradation than Iβ during enzymatic treatment [26, 27]. The same research group also observed microblock exfoliation from microfibrils in enzyme-treated Cladophora cellulose by atomic force microscopy [28], which led to the conclusion that the crystalline allomorphs are longitudinally localized rather than horizontally distributed. The formation of Iβ-rich products with smaller microfibrils during treatment also supports a model in which Iβ domains are surrounded by Iα in the microblocks that form the microfibrils. Interestingly, this model is similar to that in which Iβ domains are packed inside Iα superlattices. In addition, Iβ-rich cellulose is synthesized when acetic acid bacteria are grown in the presence of hemicellulose [29].

Cross-sectional shape of microfibrils

In order to discuss the natural cross-sectional shape diversity of microfibrils, an understanding of the method used for observing microfibril cross-sections must be mentioned first. Negatively stained transverse ultrathin sections can be imaged using electron microscopy by tilting them in various directions and at various angles [30]. The diffraction contrast method employed by Revol et al. [31] can be used for both bright-field imaging (in which all diffracted waves from the crystal are cut off by an objective aperture) and dark-field imaging (in which only diffracted waves are observed), allowing the cross-sectional shape to be determined without any need for staining.

The actual cross-sectional shape of Valonia cellulose microfibrils is square (approximately 20 × 20 nm) or rectangle [32]—similar cross-sectional shapes are observed for Oocystis and Glaucocystis [33]. However, natural celluloses with cross-sections that are neither square nor rectangular have also been observed. For example, Micrasterias, a type of aquatic algae belonging to the Zygnematales order, has a very flat microfibril cross-section [34], while ascidians have unique parallelogram- or rhomboid-shaped microfibril cross-sections [35]. The actual cross-sectional shape of wood cellulose in the gelatin layer of poplar tension wood was reported to be square (approximately 3 × 3 nm) [36]. Recent advances in scattering and imaging techniques have led to an active debate on the cross-sectional shape of microfibrils in terrestrial plants. Spectroscopic methods coupled with small-angle neutron and wide-angle X-ray scattering have suggested a “rectangular” model for microfibrils [37], while computer-simulated analyses of wide-angle X-ray scattering data resulted in a variety of microfibril models [38]. Furthermore, Daicho et al. [39] proposed a hexagonal model with boundary faces parallel to all three reflection planes of \((1{\bar 1}0)\), (110), and (200).

Preferential uniplanar orientation

The cell wall of Valonia, a green alga, has a crossed-lamellar structure. In other words, microfibrils within one lamella are deposited in a parallel arrangement, whereas those in adjacent lamellae are orthogonal. The microfibrils in both lamellae are oriented on a 0.60–0.61 nm plane [the (100) plane in Iα and the \((1{\bar 1}0)\) plane in Iβ] parallel to the cell membrane surface. In fact, the 0.53–0.54 nm plane [the (010) plane in Iα and the (110) plane in Iβ] in the Valonia cell wall exhibits a more intense peak than the 0.61 nm plane by transmission X-ray diffractometry, which indicates that the 0.61 nm plane is deposited parallel to the cell wall. In addition to the Valonia cell structure, there is a type of structure in which microfibrils are deposited with a 90° rotation; i.e., the 0.53–0.54 nm plane is oriented with the plasma membrane. The majority of microfibrils must be similarly oriented and individual microfibrils must also remain untwisted to observe a planar orientation. Consequently, rigid microfibrils with large fiber diameters and rectangular cross-sections adopt such orientations, which are common except among terrestrial plants. Ascidian [16] and bacterial [40] celluloses have been identified as types in which microfibrils are synthesized with a 0.61 nm planar orientation, as observed for Valonia. In contrast, the cellulose of Glaucocystis [33] is characterized by a plane-oriented 0.53 nm plane, as are celluloses from aquatic algae belonging to the Zygnematales order, such as Spirogyra [41], Closterium [42], and Micrasterias [34].

There are also types of cellulose that do not exhibit preferential uniplanar orientation, characterized by smaller microfibrils with individual microfibril torsion responsible for the lack of facial orientation; those of higher plants are included in this group. Packing energy calculations [9] have revealed that cellulose molecules are stable in a state slightly divergent from the twofold helix; i.e., in a twisted state. In other words, hydrophobic and hydrogen bonding interactions within a crystal are less constrained for small microfibrils, leading to a loosely twisted fibril overall.

Intracrystalline deuteration and rehydrogenation for evaluating cellulose structural diversity

Deuteration can be employed to determine the accessibilities of cellulose microfibrils and other organic macromolecules because the hydrogen involved in hydrogen bonding can be replaced by deuterium. The early literature reports the immersion of cellulose specimens in D2O, using weight differences to calculate the crystallinity, and in turn determine the structural accessibility [43]. Moreover, deuterium is useful in IR spectroscopy because the hydrogen/deuterium mass difference dramatically affects molecular vibrational frequencies, which for cellulose results in O–D bond vibrations that are located in spectral regions free from other absorbances. An IR spectrum acquired immediately after exposure of a deuterated specimen to air exhibits strong O–D bands that weaken over time owing to D/H exchange with moisture in the air.

A significant achievement was reported in 1997 in which high-temperature annealing at 260 °C in 0.1 N NaOD resulted in deuterium exchange on the microfibril surface as well as in the crystalline core without damaging the crystalline structure [44]. Despite prolonged exposure to air, rehydrogenation occurred only on the surface of the specimen, with the core remaining deuterated. By lowering the annealing temperature of the intracrystalline deuteration technique to 210 °C [45], the initial crystalline allomorph persisted, thus facilitating investigations of completely deuterated Iα and Iβ crystals separately and allowing for the precise refinement of hydrogen bonding networks of cellulose I allomorphs [16, 17].

Author and co-workers modified this intracrystalline deuteration technique to establish a stable and reproducible method to initially deuterate all of the primary hydrogen groups completely. The deuterated samples are then rehydrogenated by immersion in water at room temperature, whereby the deuterium atoms of all surface OD groups are exchanged for protons to form OH groups [46]. This behavior during rehydrogenation at elevated temperatures confers accessibility to the crystal core, thereby providing important information on microfibril dimensions [47] and uniplanar orientation [48]. In addition, monitoring exchange behavior by observing characteristic IR absorbances on Iα and Iβ during intracrystalline deuteration/rehydrogenation revealed that the Iα domain is localized on the surface as well as in the central core of the cellulose microfibril; therefore, the triclinic and monoclinic domains cannot be explained only in terms of a simple “skin–core” structure (Table 1) [49]. Recently, Funahashi et al. [50] developed a technique for peeling molecular chains from the surface of cellulose microfibrils in a layer-by-layer manner; this technique may provide new insights into the localization of cellulose allomorphs within a single microfibril.

Delignification with maintained hierarchical structures

Cellulose nanofibers are expected to be next-generation building blocks for the development of new materials because they are light and strong, with high elastic moduli and low linear expansion coefficients [51]. Various approaches have been developed to fabricate nanofibers, such as mechanical processing by grinding [52], aqueous counter collision [53], sulfamic acid treatment [54], carboxylation using succinic anhydride [55], and a combination of chemical and mechanical treatments using 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl radical (TEMPO)-mediated oxidation [56]. High-strength materials can be developed when cellulose nanofibers are aligned; however, cellulose microfibrils from terrestrial plants are extremely difficult to reorient after they have been individually dispersed in water. Bottom-up approaches use nanofibers to develop cellulosic materials that are inspired by the optimal microfibril orientation in the cell wall layer [57, 58], although perfectly imitating nature is difficult. Alternatively, top-down approaches have been proposed, in which the non-cellulosic components are removed while maintaining the hierarchical structure of the woody biomass.

In order to develop a novel material based on cellulose microfibrils supported by the hierarchical wood structure, researchers have examined top-down approaches that remove matrix components. Yano et al. reported the partial removal of lignin using NaClO2 followed by treatment with NaOH, and then impregnation with resin to obtain a high-strength wood [59]. Delignified and densified wood has been reported to exhibit excellent mechanical anisotropy [60, 61]. Optically transparent wood was first reported in 1992 by Fink [62], and recently it was also produced by delignification with NaClO2 followed by impregnation with prepolymerized methyl methacrylate [63]. Additional techniques for producing transparent wood have also been reported (e.g., solar-assisted chemical brushing [64] and UV irradiation [65]). The combination of delignification using boiling aqueous NaOH/Na2SO3 with hot pressing results in remarkably strong densified wood as well [66]. The selective separation of oil/water mixtures using strong, mesoporous, and hydrophobic biocomposites is a recent application that has been explored [67, 68].

By detailed monitoring of wood delignification using IR spectroscopy [69], our group fabricated a novel cellulose block with the natural architecture of wood through alcoholysis with ethylene glycol combined with NaClO2 [70]. Figure 1 shows a representative colorless wood block prepared using the two-step delignification process and a schematic model of the hierarchical structure of wood with the corresponding morphological and structural data obtained from different analytical techniques. This delignified wood is unique in that most of the hemicellulose has also been removed. Author and co-workers have further improved the technique and demonstrated its applicability to bamboo [71]. In addition, non-cellulosic components were removed from wood blocks by changing the treatment conditions to generate cellulose blocks with varying degrees of polymerization while maintaining the anatomical structure [72]. The microfibril sheets oriented by heat-pressing exhibited desirable physical properties (Fig. 2), with the specific modulus independent of the degree of polymerization as long as the orientation was maintained. In contrast, the tensile strength of the oriented sheet varied with the degree of polymerization, which highlights the notable influence of single fiber strength compared to the randomly oriented sheet. Lignin-free wood blocks, which are supported by the three-dimensional (3D) architecture of wood, have great potential as new materials, which can also be used to understand the formation and functionality of the structure of wood.

Development of colorless wood by two-step delignification and structural analysis of the hierarchical architecture (reproduced from [70])

Tensile stress–strain curves for an oriented sheet and a random sheet prepared by pressing colorless wood (reproduced from [72])

Conclusion

Primitive organisms such as bacteria and sea algae synthesize relatively large cellulose fibers. In contrast, terrestrial plants generate small microfibrils, possibly to increase their surface area and facilitate interactions with matrix components, such as lignin and hemicellulose, which helps their survival under harsh environmental conditions. Given the long history of trees on Earth, the complex 3D structure of wood underpinned by cellulose provides the exemplary structure as a high-strength material. Consequently, new functional materials with guaranteed strengths may be developed using colorless wood as a framework and injecting matrix components other than lignin. In addition, incorporating selective lignin polymerization technology into colorless wood [73] may further clarify the relationship between the chemical composition and physical properties of wood.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- IR:

-

Infrared

- NMR:

-

Nuclear magnetic resonance

- TEMPO:

-

2,2,6,6-Tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl

References

Motaung TE, Linganiso LZ (2018) Critical review on agrowaste cellulose applications for biopolymers. Int J Plast Technol 22:185–216. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12588-018-9219-6

Nishikawa S, Ono S (1913) Transmission of X-Rays through fibrous, lamellar and granular substances. Proc Tokyo Math-Phys Società 2(7):131–138

Meyer KH, Mark H (1928) Über den Bau des krystallisierten Anteils der Cellulose. Ber Dtsch Chem Ges A/B 61:593–614. https://doi.org/10.1002/cber.19280610402

Meyer KH, Misch L (1937) Positions des atomes dans le nouveau modèle spatial de la cellulose. Helv Chim Acta 20:232–244. https://doi.org/10.1002/hlca.19370200134

Honjo G, Watanabe M (1958) Examination of cellulose fibre by the low-temperature specimen method of electron diffraction and electron microscopy. Nature 181:326–328. https://doi.org/10.1038/181326a0

Marrinan HJ, Mann J (1956) Infrared spectra of the crystalline modifications of cellulose. J Polym Sci 21:301–311. https://doi.org/10.1002/pol.1956.120219812

Mann J, Marrinan HJ (1958) Crystalline modifications of cellulose. Part II. A study with plane-polarized infrared radiation. J Polym Sci 32:357–370. https://doi.org/10.1002/pol.1958.1203212507

Fisher DG, Mann J (1960) Crystalline modifications of cellulose. Part VI. Unit cell and molecular symmetry of cellulose I. J Polym Sci 42:189–194. https://doi.org/10.1002/pol.1960.1204213921

Sarko A, Muggli R (1974) Packing analysis of carbohydrates and polysaccharides. III Valonia cellulose and cellulose II. Macromolecules 7:486–494. https://doi.org/10.1021/ma60040a016

Gardner KH, Blackwell J (1974) The structure of native cellulose. Biopolymers 13:1975–2001. https://doi.org/10.1002/bip.1974.360131005

Atalla RH, VanderHart DL (1984) Native cellulose: a composite of two distinct crystalline forms. Science 223:283–285. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.223.4633.283

VanderHart DL, Atalla RH (1984) Studies of microstructure in native celluloses using solid-state carbon-13 NMR. Macromolecules 17:1465–1472. https://doi.org/10.1021/ma00138a009

Yamamoto H, Horii F, Odani H (1989) Structural changes of native cellulose crystals induced by annealing in aqueous alkaline and acidic solutions at high temperatures. Macromolecules 22:4130–4132. https://doi.org/10.1021/ma00200a058

Debzi EM, Chanzy H, Sugiyama J, Tekely P, Excoffier G (1991) The Iα →Iβ transformation of highly crystalline cellulose by annealing in various mediums. Macromolecules 24:6816–6822. https://doi.org/10.1021/ma00026a002

Sugiyama J, Vuong R, Chanzy H (1991) Electron diffraction study on the two crystalline phases occurring in native cellulose from an algal cell wall. Macromolecules 24:4168–4175. https://doi.org/10.1021/ma00014a033

Nishiyama Y, Langan P, Chanzy H (2002) Crystal structure and hydrogen-bonding system in cellulose Iβ from synchrotron X-ray and neutron fiber diffraction. J Am Chem Soc 124:9074–9082. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja0257319

Nishiyama Y, Sugiyama J, Chanzy H, Langan P (2003) Crystal structure and hydrogen bonding system in cellulose Iα from synchrotron X-ray and neutron fiber diffraction. J Am Chem Soc 125:14300–14306. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja037055w

Sugiyama J, Persson J, Chanzy H (1991) Combined infrared and electron diffraction study of the polymorphism of native celluloses. Macromolecules 24:2461–2466. https://doi.org/10.1021/ma00009a050

Wada M, Sugiyama J, Okano T (1993) Native celluloses on the basis of two crystalline phase (Iα/Iβ) system. J Appl Polym Sci 49:1491–1496. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.1993.070490817

Nakashima K, Nishino A, Horikawa Y, Hirose E, Sugiyama J, Satoh N (2011) The crystalline phase of cellulose changes under developmental control in a marine chordate. Cell Mol Life Sci 68:1623–1631. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-010-0556-7

Horikawa Y (2017) Assessment of cellulose structural variety from different origins using near infrared spectroscopy. Cellulose 24:5313–5325. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-017-1518-0

Wang H, Tsuchikawa S, Inagaki T (2021) Terahertz time-domain spectroscopy as a novel tool for crystallographic analysis in cellulose: the potentiality of being a new standard for evaluating crystallinity. Cellulose 28:5293–5304. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-021-03902-x

Imai T, Sugiyama J (1998) Nanodomains of Iα and Iβ cellulose in algal microfibrils. Macromolecules 31:6275–6279. https://doi.org/10.1021/ma980664h

Yamamoto H, Horii F, Hirai A (1996) In situ crystallization of bacterial cellulose II. Influences of different polymeric additives on the formation of celluloses Iα and Iβ at the early stage of incubation. Cellulose 3:229–242. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02228804

Wada M, Okano T (2001) Localization of Iα and Iβ phases in algal cellulose revealed by acid treatments. Cellulose 8:183–188. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1013196220602

Hayashi N, Sugiyama J, Okano T, Ishihara M (1997) Selective degradation of the cellulose Iα component in Cladophora cellulose with Trichoderma viride cellulase. Carbohydr Res 305:109–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0008-6215(97)00281-4

Hayashi N, Sugiyama J, Okano T, Ishihara M (1997) The enzymatic susceptibility of cellulose microfibrils of the algal-bacterial type and the cotton-ramie type. Carbohydr Res 305:261–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0008-6215(97)10032-5

Hayashi N, Kondo T, Ishihara M (2005) Enzymatically produced nano-ordered short elements containing cellulose Iβ crystalline domains. Carbohydr Polym 61:191–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2005.04.018

Hackney JM, Atalla RH, Vanderhart DL (1994) Modification of crystallinity and crystalline structure of Acetobacter xylinum cellulose in the presence of water-soluble β-1,4-linked polysaccharides: 13C-NMR evidence. Int J Biol Macromol 16:215–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/0141-8130(94)90053-1

Goto T, Harada H, Saeki H (1973) Cross-sectional view of microfibrils in Valonia (Valonia macrophysa). Mokuzai Gakkaishi 19:463–468

Revol J-F (1982) On the cross-sectional shape of cellulose crystallites in Valonia ventricosa. Carbohydr Polym 2:123–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/0144-8617(82)90058-3

Sugiyama J, Harada H, Fujiyoshi Y, Ueda N (1984) High resolution observations of cellulose microfibrils. Mokuzai Gakkaishi 30:98–99

Imai T, Sugiyama J, Itoh T, Horii F (1999) Almost pure Iα cellulose in the cell wall of Glaucocystis. J Struct Biol 127:248–257. https://doi.org/10.1006/jsbi.1999.4160

Kim NH, Herth W, Vuong R, Chanzy H (1996) The cellulose system in the cell wall of Micrasterias. J Struct Biol 117:195–203. https://doi.org/10.1006/jsbi.1996.0083

Van Daele Y, Revol JF, Gaill F, Goffinet G (1992) Characterization and supramolecular architecture of the cellulose-protein fibrils in the tunic of the sea peach (Halocynthia papillosa, Ascidiacea, Urochordata). Biol Cell 76:87–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/0248-4900(92)90198-A

Goto T, Harada H, Saeki H (1975) Cross-sectional view of microfibrils in gelatinous layer of poplar tension wood (Populus euramericana). Mokuzai Gakkaishi 21:537–542

Fernandes AN, Thomas LH, Altaner CM, Callowd P, Forsyth VT, Apperley DC, Kennedy CJ, Jarvis MC (2011) Nanostructure of cellulose microfibrils in spruce wood. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108:E1195–E1203. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1108942108

Newman RH, Hill SJ, Harris PJ (2013) Wide-angle X-ray scattering and solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance data combined to test models for cellulose microfibrils in mung bean cell walls. Plant Physiol 163:1558–1567. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.113.228262

Daicho K, Saito T, Fujisawa S, Isogai A (2018) The crystallinity of nanocellulose: Dispersion-induced disordering of the grain boundary in biologically structured cellulose. ACS Appl Nano Mater 1:5774–5785. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsanm.8b01438

Liang CY, Marchessault RH (1960) Infrared spectra of crystalline polysaccharides. IV. The use of inclined incidence in the study of oriented films. J Polym Sci 43:85–100. https://doi.org/10.1002/pol.1960.1204314108

Kreger DR (1957) New crystallite orientations of cellulose I in Spirogyra cell-walls. Nature 180:914–915. https://doi.org/10.1038/180914a0

Koyama M, Sugiyama J, Itoh T (1997) Systematic survey on crystalline features of algal celluloses. Cellulose 4:147–160. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1018427604670

Frilette VJ, Hanle J, Mark H (1948) Rate of exchange of cellulose with heavy water. J Am Chem Soc 70:1107–1113. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja01183a071

Wada M, Okano T, Sugiyama J (1997) Synchrotron-radiated X-ray and neutron diffraction study of native cellulose. Cellulose 4:221–232. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018435806488

Nishiyama Y, Isogai A, Okano T, Müller M, Chanzy H (1999) Intracrystalline deuteration of native cellulose. Macromolecules 32:2078–2081. https://doi.org/10.1021/ma981563m

Horikawa Y, Sugiyama J (2008) Accessibility and size of Valonia cellulose microfibril studied by combined deuteration/rehydrogenation and FTIR technique. Cellulose 15:419–424. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-007-9187-z

Horikawa Y, Clair B, Sugiyama J (2009) Varietal difference in cellulose microfibril dimensions observed by infrared spectroscopy. Cellulose 16:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-008-9252-2

Horikawa Y, Itoh T, Sugiyama J (2006) Preferential uniplanar orientation of cellulose microfibrils reinvestigated by the FTIR technique. Cellulose 13:309–316. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-005-9037-9

Horikawa Y (2009) Sugiyama J Localization of crystalline allomorphs in cellulose microfibril. Biomacromol 10:2235–2239. https://doi.org/10.1021/bm900413k

Funahashi R, Okita Y, Hondo H, Zhao M, Saito T, Isogai A (2017) Different conformations of surface cellulose molecules in native cellulose microfibrils revealed by layer-by-layer peeling. Biomacromol 18:3687–3694. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.biomac.7b01173

Isogai A (2015) Structural characterization and modifications of surface-oxidized cellulose nanofiber. J Jpn Petrol Inst 58:365–375. https://doi.org/10.1627/jpi.58.365

Abe K, Iwamoto S, Yano H (2007) Obtaining cellulose nanofibers with a uniform width of 15 nm from wood. Biomacromol 8:3276–3278. https://doi.org/10.1021/bm700624p

Kose R, Mitani I, Kasai W, Kondo T (2011) ‘Nanocellulose’ as a single nanofiber prepared from pellicle secreted by Gluconacetobacter xylinus using aqueous counter collision. Biomacromol 12:716–720. https://doi.org/10.1021/bm1013469

Briois B, Saito T, Pétrier C, Putaux J-L, Nishiyama Y, Heux L, Molina-Boisseau S (2013) Iα → Iβ transition of cellulose under ultrasonic radiation. Cellulose 20:597–603. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-013-9866-x

Sehaqui H, Kulasinski OK, Pfenninger ON, Zimmermann T, Tingaut P (2017) Highly carboxylated cellulose nanofibers via succinic anhydride esterification of wheat fibers and facile mechanical disintegration. Biomacromol 18:242–248. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.biomac.6b01548

Saito T, Kimura S, Nishiyama Y, Isogai A (2007) Cellulose nanofibers prepared by TEMPO-mediated oxidation of native cellulose. Biomacromol 8:2485–2491. https://doi.org/10.1021/bm0703970

Kobayashi Y, Saito T, Isogai A (2014) Aerogels with 3D ordered nanofiber skeletons of liquid-crystalline nanocellulose derivatives as tough and transparent insulators. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 53:10394–10397. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201405123

Nechyporchuk O, Håkansson KMO, Gowda VK, Lundell F, Hagström B, Köhnke T (2019) Continuous assembly of cellulose nanofibrils and nanocrystals into strong macrofibers through microfluidic spinning. Adv Mater Technol 4:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1002/admt.201800557

Yano H, Hirose A, Collins PJ, Yazaki Y (2001) Effects of the removal of matrix substances as a pretreatment in the production of high strength resin impregnated wood based materials. J Mater Sci Lett 20:1125–1126. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010992307614

Jakob M, Gaugeler J, Gindl-Altmutter W (2020) Effects of fiber angle on the tensile properties of partially delignified and densified wood. Materials (Basel) 13:5405. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13235405

Frey M, Widner D, Segmehl JS, Casdorff K, Keplinger T, Burgert I (2018) Delignified and densified cellulose bulk materials with excellent tensile properties for sustainable engineering. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 10:5030–5037. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.7b18646

Fink S (1992) Transparent wood—a new approach in the functional study of wood structure. Holzforschung 46:403–408. https://doi.org/10.1515/hfsg.1992.46.5.403

Li YY, Fu QL, Yu S, Yan M, Berglund L (2016) Optically transparent wood from a nanoporous cellulosic template: Combining functional and structural performance. Biomacromol 17:1358–1364. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.biomac.6b00145

Xia Q, Chen C, Li T, He S, Gao J, Wang X, Hu L (2021) Solar-assisted fabrication of large-scale, patternable transparent wood. Sci Adv. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abd7342

Samanta A, Chen H, Samanta P, Popov S, Sychugov I, Berglund LA (2021) Reversible dual-stimuli-responsive chromic transparent wood biocomposites for smart window applications. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 13:3270–3277. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.0c21369

Song JW, Chen CJ, Zhu SZ, Zhu MW, Dai JQ, Ray U, Li YJ, Kuang YD, Li YF, Quispe N, Yao YG, Gong A, Leiste UH, Bruck HA, Zhu JY, Vellore A, Li H, Minus ML, Jia Z, Martini A, Li T, Hu LB (2018) Processing bulk natural wood into a high-performance structural material. Nature 554:224–228. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature25476

Fu Q, Ansari F, Zhou Q, Berglund LA (2018) Wood nanotechnology for strong, mesoporous, and hydrophobic biocomposites for selective separation of oil/water mixtures. ACS Nano 12:2222–2230. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.8b00005

Wang K, Liu X, Tan Y, Zhang W, Zhang S, Li J (2019) Two-dimensional membrane and three-dimensional bulk aerogel materials via top-down wood nanotechnology for multibehavioral and reusable oil/water separation. Chem Eng J 371:769–780. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2019.04.108

Horikawa Y, Hirano S, Mihashi A, Kobayashi Y, Zhai S, Sugiyama J (2019) Prediction of lignin contents from infrared spectroscopy: chemical digestion and lignin/biomass ratios of Cryptomeria japonica. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 188:1066–1076. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12010-019-02965-8

Horikawa Y, Tsushima R, Noguchi K, Nakaba S, Funada R (2020) Development of colorless wood via two-step delignification involving alcoholysis and bleaching with maintaining natural hierarchical structure. J Wood Sci 66:37. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10086-020-01884-1

Kurei T, Tsushima R, Okahisa Y, Nakaba S, Funada R, Horikawa Y (2021) Creation and structural evaluation of the three-dimensional cellulosic material “White-Colored Bamboo.” Holzforschung 75:180–186. https://doi.org/10.1515/hf-2020-0030

Kurei T, Hioki Y, Kose R, Nakaba S, Funada R, Horikawa Y (2021) Effects of orientation and degree of polymerization on tensile properties in the cellulose sheets using hierarchical structure of wood. Cellulose 29:2885–2898. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-021-04160-7

Hirano S, Yamagishi Y, Nakaba S, Kajita S, Funada R, Horikawa Y (2020) Artificially lignified cell wall catalyzed by peroxidase selectively localized on a network of microfibrils from cultured cells. Planta 251:104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00425-020-03396-0

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Mr. Adachi of Kyoto University for providing wood samples, and Mr. Seiya Hirano, Ms. Rino Tsushima, and Mr. Tatsuki Kurei of Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology for support related to data collection and analysis provided for some of the work reported herein. Finally, I express my sincere gratitude to Prof. Junji Sugiyama of Kyoto University for providing the opportunity to study cellulose and wood science.

Funding

Some of the work reported herein was jointly supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) [Grant No. 19K06167 and 22K19203] from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YH conceptualized the research, conducted a literature review, and wrote the manuscript. The author read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Horikawa, Y. Structural diversity of natural cellulose and related applications using delignified wood. J Wood Sci 68, 54 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s10086-022-02061-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s10086-022-02061-2