Abstract

Background

Foraging movements of animals shape their efficiency in finding food and their exposure to the environment while doing so. Our goal was to test the optimal foraging theory prediction that territorial acorn woodpeckers (Melanerpes formicivorus) should forage closer to their ‘central place’ in years of high resource availability and further afield when resources are less available. We used genetic data on acorns stored in caching sites (granaries) and adult trees for two oak species (Quercus lobata and Quercus agrifolia) to track acorn movements across oak savanna habitat in central California. We also compared the patterns of trees these territorial bird groups foraged upon, examining the effective numbers of source trees represented within single granaries (α), the effective number of granaries (β), the diversity across all granaries (γ), and the overlap (ω) in source trees among different granaries, both within and across years.

Results

In line with optimal foraging theory predictions, most bird groups foraged shorter distances in years with higher acorn abundance, although we found some exceptionally long distance foraging movements in high acorn crop years. The α-diversity values were significantly higher for Quercus lobata, but not for Quercus agrifolia, in years of high acorn production. We also found that different woodpecker family groups visited almost completely non-overlapping sets of source trees, and each particular group visited largely the same set of source trees from year to year, indicating strong territorial site fidelity.

Conclusions

Acorn woodpeckers forage in a pattern consistent with optimal foraging theory, with a few fascinating exceptions of long distance movement. The number of trees they visit increases in years of high acorn availability, but the extra trees visited are mostly local. The territorial social behavior of the birds also restricts their movement patterns to a minimally overlapping subsets of trees, but the median movement distance appears to be shaped more by the availability of trees with acorns than by rigid territorial boundaries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Understanding the factors influencing patterns of animal foraging movements is a long-standing research goal of behavioral ecology. Such movements determine a forager’s efficiency in finding food and vulnerability to predators, both of which impact forager fitness. Much of the theory regarding foraging behavior is grounded in Optimal Foraging Theory (OFT), which predicts that a forager will maximize energy intake over time [1–3]. This optimal model can take many forms. Animals may forage efficiently by either being ‘energy maximizers’ or ‘time minimizers’ [4], and time invested in foraging can be translated into the distance a forager must move in search of resources [5]. Additionally, some foragers may have a ‘central place’ to which they must return after foraging, and this behavioral feature impacts both how they will forage and the optimality predictions [6–8]. Thus, if an animal is foraging optimally and must return to a central place, OFT predicts that it will forage in patches close to that central place, unless the energy gained from a more distant patch is higher than the energy expended in travel [3, 9].

Both environmental factors and intrinsic behaviors can be expected to modify an animal’s foraging strategy, and ‘optimality’ is context dependent. One important factor is the degree of spatial and temporal variation in resource availability [10]. Many studies have shown that variations in resource levels can influence foraging processes [11–13], and that studies across multiple seasons/years are critical to understanding general principles of how extrinsic factors influence animal foraging movements [10]. If animals perceive that resource levels in a patch are unpredictable in space and time, they may choose to forage in ways that minimize risk of starvation, but do not conform to classic OFT predictions [14–16]. For example, in foraging choice experiments with birds [17, 18] and bumblebees [14], animals chose food with smaller but more consistently available energy. Other experiments have shown the high degree of plasticity in animal foraging strategies [19], and particular patterns of prey density can drive typically ‘risk-averse’ foragers into ‘risk-prone’ behavior [20, 21].

Energetic considerations aside, highly territorial animals are constrained to foraging within territories, with different territorial groups exhibiting largely non-overlapping foraging ranges [22–24]. Territorial defense of resources might be expected to modify energetic choices. For example, Kacelnik et al. [25] found that great tits were more likely to forage optimally when risk of territorial intrusion was lowered. Many models of ‘optimal territoriality’ have been devised, each with minor differences in assumptions, resulting in conflicting predictions [26]. Empirical studies on how territorial animals change the size of their territories in response to changes in resource abundance remain equivocal [27–29], indicating a need for more case studies to establish how territorial species forage, and whether these patterns conform to OFT predictions.

A standard procedure of tracking foraging movements is to observe the foragers directly, recording the distance traveled and resources visited. However, many foragers, particularly bird species, are difficult to observe, and long distance movements are often missed entirely [22, 30, 31]. This difficulty has inspired many innovative approaches to tracking animals based on the movements of the foraged-upon resource, including methods such as tracking seeds with telemetric threads [32], and enriching seeds with stable isotopes [33]. These techniques have enhanced our ability to track elusive long-distance dispersal events, and can illuminate interesting aspects of animal behavior, such as the propensity of agoutis to re-cache seeds from other caches, thereby moving seeds up to 36 times [34]. An alternative approach is to use plant genetic markers to document the distance between the original foraging location and the deposition site of the granivore or frugivore [35–37]. These techniques not only make indirect observations of animal foraging movements possible, but, for researchers interested in seed dispersal by vertebrates, they can be used to document the impact of foraging patterns on plant genetic diversity across the landscape [38]. Using recently developed diversity measures [39], we can assess the effective number of trees a forager visits by examining the diversity of maternal seed sources found within a caching site, between sites, and across all caches within a region. In addition, these diversity measures can be used to estimate the shared use of foraging trees between pairs of caches (which represents a measure of territoriality) or between years (which represents site fidelity). These statistics, taken collectively, provide a summary of an animal’s foraging movements across space and time.

Here, we analyze the pattern and outcomes of acorn woodpecker (Melanerpes formicivorus) foraging by tracking acorn movements for two species of oaks (Quercus lobata Née and Quercus agrifolia Née). Using known genotypes from neutral genetic markers (nuclear microsatellites) and the spatial locations of trees, we are able to determine the maternal source tree of any particular acorn in an acorn woodpecker granary (acorn caching site), and calculate the spatial distance between these two points. In the process, we can reconstruct a much larger number of woodpecker foraging flights than are directly observable [40]. We sampled two different oak species, each across two years, providing independent tests of OFT predictions, as related to resource abundance of the two oak species. Koenig et al. [23] first proposed that acorn woodpeckers foraged optimally, when they observed four bird family groups in central California visiting more trees and flying further in a bad acorn crop year. In this study we test similar predictions, but use genetic markers to analyze a greater number of foraging flights, at a different study site. Our objectives were to: (1) compare foraging movements across years by tracking distances that birds moved acorns from source trees to granaries for multiple family groups in two oak species; (2) assess effective numbers of source trees visited by different social groups (α-diversity), the effective number of granaries used by the bird groups (β-diversity), the accumulated number of seed trees foraged upon for the entire study site (γ-diversity), and the extent to which different social groups foraged on the same or different source trees (ω-overlap), both within and across years.

Results and discussion

Granaries and source trees

Between 2002 and 2007, using acorns sampled from every active granary within the study region, we identified source trees and number of source trees per granary (Table 1), using a modified parentage analysis. For Q. lobata, we found 18 granaries in 2002 and 14 granaries in 2004. For Q. agrifolia, we found 16 granaries in 2006 and 13 granaries in 2007. For each species, we found a subset of granaries that contained acorns in both years: nine for Q. lobata (2002 and 2004) and seven for Q. agrifolia (2006 and 2007).

Patterns of foraging movements

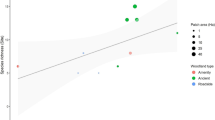

Based on our personal observations and on Koenig and Knops’ acorn surveys at Sedgwick, we categorized each particular year for each of the two oak species as a ‘high’, ‘medium’ or ‘low’ year. For Q. lobata, 2002 was a high crop year, and 2004 was a low crop year. For Q. agrifolia, 2006 was a high crop year, and 2007 was a medium crop year. Across all four years, acorn woodpeckers foraged mostly on local trees and both oak species, but with occasional long distance foraging forays (Figure 1).

To test the OFT predictions, we restricted attention to granaries sampled in both high and low crop years, allowing us to gauge how the same family groups responded to differences in resource availability over time. In this comparison, birds carrying Q. agrifolia acorns foraged significantly closer to the granary during high crop years (m06 = 53.6 m < m07 = 78.1 m; Table 2), while birds carrying Quercus lobata acorns also tended to forage closer to the granary in high crop years, but marginally so (m02 = 50.7 m < m04 = 52.0 m; Table 2). Using a nested Mann–Whitney-Wilcoxson rank order test, we demonstrated that median transport distance of Q. agrifolia acorns was significantly greater in medium years than in good years (P < 0.0001, Figure 2B), while Q. lobata acorns showed slightly longer median distances in bad than in good years, though not quite significantly so (P = 0.0596, Figure 2A).

Frequency plots of weighted Z-scores. Distribution of weighted nested Mann–Whitney-Wilcoxson rank order scores permutated within granary for Q. lobata (A) and Q. agrifolia (B) and the actual average value indicated by dashed line and its associated P-value. P-values test whether the difference of foraging movement in bad years minus distance moved in good years is significantly greater than zero. (See text and Additional file 1 for detail).

It is worth noting that woodpeckers establish granaries in Q. lobata trees, but never in Q. agrifolia trees, which yields many foraging distances of zero during high and low years of Q. lobata acorn production (Figure 3). It is possible that woodpeckers deliberately locate granaries in Q. lobata trees with good acorn crops, which would be consistent with OFT. In 2002, 56 of the 181 total acorns in granaries were from a granary tree; in 2004, 40 of the 150 total acorns were from their granary tree. When we exclude the (zero-distance) acorns sampled from the granaries themselves, the data indicate that woodpeckers foraged significantly closer to (non-granary) Q. lobata trees in a high crop year than in a low crop year (m02 = 52.0 m < m04 = 79.5 m). Therefore, granaries located in a tree with high acorn production allow the woodpeckers to forage closer to their territory in both high and low crop years for Q. lobata, and their remaining foraging trips (away from the home tree) also follow OFT predictions.

Maps of foraging flights. GIS maps of woodpecker foraging flights, from all acorns and granaries sampled in Q. lobata during years 2002 (A) and 2004 (B) and Q. agrifolia in years 2006 (C) and 2007 (D), showing locations of all trees of the species of interest (gray circles), granaries (open squares), and source trees (black circles). Lines between the granaries and source trees are un-weighted with regard to acorn frequency. Granaries that were also source trees (only the case for Q. lobata) are symbolized with a square filled with a black circle.

Despite the prevalence of short distance flights, the maps of all foraging flights provide a useful perspective on foraging movement and they show several longer flights that seem inconsistent with OFT predictions (Figure 3). We recorded a few flights of > 1.5 km in 2002 and 2006, both years of high acorn production for the respective species, in contrast to the majority of acorn collecting trips, which range no more than 100 meters from the granaries. Koenig et al. [30] observed similar long distance flights in poor crop years, but the longest foraging movement they observed was 796 m, whereas we have (using acorn genotypes) inferred 17 foraging flights of over 1 km (1.72% of the total number of foraging movements). These long distance movements may reflect interesting consequences of the social organization of acorn woodpeckers, such as movement of territories between years or social group fissions [22], which are better studied with direct behavioral observations of the birds. For example, Hannon et al. [41] noted that emigration of non-breeding group members away from territories was linked to poor acorn crop years. The interesting point here is that these long distance movements are exceptions to the pattern that foraging tends to be spatially more restricted in good than in bad years.

As we examine the flight patterns of acorn woodpeckers in high versus lower crop years, we find a seeming paradox with respect to the energetics of foraging. There are more long- distance flights in the high crop year, but the median of good-year flights is nevertheless shorter. By contrast, acorn woodpeckers may be forced to fly further to find acorn-yielding trees in lower crop years, but, given the infrequency of such trees, long distance flights are less likely to be successful. It is difficult to know how metabolically costly these foraging flights are without collecting data on daily energy budgets, but we know that stored acorns can be critical to acorn woodpecker survival. Koenig and Mumme [42] note that stored acorns represent a small part of the social group’s overall energetic needs, but that these stores are probably used by adults to pass an energetic threshold, after which they can breed. The authors surmise that acorn woodpeckers have tight constraints on obtaining enough energy [42], strengthening our inference these birds may forage with optimal energy in mind.

Outcomes of foraging movements: source tree diversity

Distance is not the only relevant determinant of foraging pattern, and our assessment of the seed diversity in granaries enhances our understanding of how acorn woodpeckers utilize resources. Using the entire dataset, we can assess whether bird groups adjust their foraging patterns across years with different resource levels. Do acorn woodpeckers forage ‘optimally’ in years of high acorn production by visiting a few local trees, or do they visit many trees in the immediate vicinity? For Q. lobata, we found greater within-granary source diversity in the high crop year than in the low crop year (α02 = 1.85 > α04 = 1.38, P < 0.01; Table 3), but for Q. agrifolia, the difference between high and medium crop years was trivial (α06 = 1.62 ≈ α07 = 1.61, P = 0.53; Table 3). These findings suggest that acorn woodpeckers may visit more trees when they are available, even while foraging locally, which may reflect lower opportunity costs to an optimal forager in high-resource years [43]. In general, however, the effective number of trees is typically quite small (α < 2 source trees per granary), probably reflecting a limitation in the number of Quercus trees available within the territory [22, 30, 40].

The total (γ) diversity of source trees across the valley was significantly higher in high acorn crop years for both Q. lobata (γ02 = 18.45 > γ04 = 10.81, P < 0.003) and Q. agrifolia (γ06 = 17.07 > γ07 = 10.86, P < 0.001, Table 3). The ‘turnover diversity’ (β), the effective number of granaries/territories can be defined as β = (γ/α), which evidently changes from year to year, depending on overall resource availability. The trend of higher effective numbers of granaries in higher acorn crop years is clear (βlo-02 = 9.95 ≥ βlo-04 = 7.85; βag-06 = 10.52 ≥ βag-07 = 6.77). In effect, when acorn-producing trees are abundant, the valley can sustain more territorial family groups (via granaries), suggesting a tradeoff between lower opportunity costs due to the greater (valley-wide) availability of resources and higher costs of territorial defense, due to a more dense packing of territorial family groups. In addition, resource availability across oak species may also shape how many trees are visited, but we were unable to assess that factor in this study. Nonetheless, all of these factors may influence group fission and fusion, with young birds fledging and forming new territories in good years [42], which may help to explain the few long distance movements we observed in those years [22]. We know that low acorn crop years may cause territory abandonment by groups [42], and so it is possible that unused/abandoned granary sites in a bad year may be a resource to fledging birds in a subsequent good year.

As noted above, one additional consideration is the territorial influence of other acorn woodpecker groups at the study site. We have deployed ω values to gauge the overlap in source tree utilization among social groups, which provides a useful measure to assess the impact of territoriality on acorn foraging [36, 39, 40]. Here, overlap in source tree use was essentially zero between different granaries, suggesting that different foraging groups very rarely shared source trees. The average overlap estimates for Q. lobata were (ω02 = 0.05 and ω04 = 0.03, P < 0.001), while those for Q. agrifolia were (ω06 = 0.003 and ω07 = 0.06, P < 0.001) (Table 4). Thus, in addition to OFT energetic considerations, territoriality strongly shapes where birds forage.

By contrast, the average overlap in utilization of source trees by woodpecker groups across years indicates the degree to which territorial groups consistently forage from the same source trees. We found variation in overlap from 0–1 among the family groups sampled in both years, and higher average overlap (across all family groups) in source tree use between years for Q. lobata (ω02–04 = 0.71) than for Q. agrifolia (ω06–07 = 0.41), supporting other work asserting Q. lobata is the preferred food item of the two oak species [44]. We have previously considered this diversity parameter to be a measure of territorial fidelity [22, 39, 40], but from a resource standpoint, this overlap measure can also be construed as source tree fidelity, possibly due to the woodpeckers’ memory for good trees or to the tendency of the same trees being the best acorn producers across years. Evidence supports both possibilities: foraging site fidelity in birds is well documented [45–47] and it is commonly observed that some individual oak trees are more consistent in their acorn production than others [48–50].

Our results indicate that source tree diversity patterns can be used to infer a suite of interesting behavioral phenomena about the forager, including plasticity in response to resource abundance, territoriality, and possibly foraging site fidelity. Conversely, different types of social and foraging behaviors will impact the seed diversity outcomes, as can be seen in studies of foragers with a different social organization. For example, Karubian et al. [37] used genetic markers to track foraging flights of male long-wattled umbrella birds (Cephalopterus penduliger), which forage very widely to find Oenocarpus palm nuts but return to a lekking site and regurgitate seeds at the lek. Males forage in groups and need to move long distances from the lek to find enough food resources, which results in seed pools at lek sites with high α diversity and high ω overlap [39]. These α and ω patterns contrast with those shown here for the foraging caches of acorn woodpecker social groups [39]. Thus, the pattern of movement for a given species must be assessed in the context of its social behavior, which will shape its movements [51]. The optimal choice will be context-dependent.

Conclusions

Overall, we found evidence that variation in resource levels from year to year shapes the movement patterns of acorn woodpeckers, largely in the direction predicted by classic OFT. Birds moved shorter distances to gather acorns, but used greater numbers and a wider variety of source trees in high crop years than lower crop years, and these patterns were similar for both oak species used as a resource. Our findings also indicate that the social behavior of the acorn woodpeckers constrained their movement patterns. Our ability to detect both distances and details of foraging movements improves with the use of genetic data from the plant species foraged upon, and represents a valuable addition to our tool kit for animal movement studies. In short, seeds tell us quite a bit about birds.

Methods

Study site

This project was conducted at the UC Santa Barbara Sedgwick Reserve near Los Olivos, Santa Barbara County, California, specifically in Figueroa Creek Valley (34°42′ N, 120°02′ W), an area of approximately 130 hectares. The valley is an oak savannah ecosystem with clusters of adults and a density of about 12 trees per hectare [52]. The site is our long-term focal area for numerous studies [22, 36, 52–56] where the locations of all Q. lobata and Q. agrifolia in the valley have been GPS mapped and the trees have been genotyped.

Study species

The acorn woodpecker (Melanerpes formicivorous) is a common California bird species, closely associated with oak woodlands throughout the birds’ range. The birds form territorial social groups of breeding adults and related juveniles of both sexes [42]. Acorns are a central part of acorn woodpecker diet, and acorn storage is strongly correlated with bird survival over the winter [42]. Each social group stores acorns by creating holes in the sides of trees and other woody structures, in a centralized granary. Granaries are defended against other groups, and are typically defended by the same social group from year to year, becoming the focal point of the group’s territory [42, 57]. Granaries are typically found in Q. lobata and Q. douglasii trees both of which have thick, cracked bark, but not in Q. agrifolia trees, with smooth hard bark [57].

Two focal food resources used by acorn woodpeckers at our study site are valley oak (Quercus lobata Née) and coast live oak (Quercus agrifolia Née). Valley oak is a deciduous species found mostly in the valley floor at our study site, while live oak is found on the valley floor and hillsides. Acorns mature in the fall and are dispersed by gravity and a variety of seed predators, including acorn woodpeckers (mostly seed predators), scrub jays, and small rodents. Variation in acorn production among years is high in both oak species [50]. Even though Q. agrifolia acorns have higher energetic value per gram than Q. lobata, woodpeckers tend to store acorns from both species, possibly due to the higher tannin content of Q. agrifolia acorns [44, 58]. Acorn woodpeckers also eat green acorns off of oak trees, insects (which are often fed to nestlings) and sap [42].

Sample design

During 2002 through 2007, we surveyed the Figueroa Creek Valley at our study site to identify active granaries (ones with acorns), which our research group used for several different projects [22, 36, 40, 52–56]. Our goal was to collect 50 acorns from each granary; when 50 acorns were not available, we sampled as many as we could find. We initially focused solely on Q. lobata, but switched our efforts to Q. agrifolia in 2006 and 2007, when there were very few Q. lobata acorns present in any granaries. Our final data set of acorns reflect these sampling realities.

Our personal observations of acorn production indicate that Q. lobata produced dramatically more acorns in 2002 than in 2004, and that Q. agrifolia produced somewhat more acorns in 2006 than 2007. In support of this pattern, we have data on acorn abundance from a statewide survey by Koenig and Knops [59], who made canopy acorn counts for a different set of 11 Q. lobata trees and 19 Q. agrifolia trees at Sedgewick Reserve during 2002–2007. Their average acorn counts for Q. lobata were C02 = 36.8, C04 = 8.4, and for Q. agrifolia were C06 = 64.1 and C07 = 36.6.

Acorn assignment to seed source trees

We extracted DNA from the embryos and pericarps (diploid maternal tissue) from acorns, and amplified microsatellites at six to ten loci, following the protocols in [22, 36]. The 2002, 2004 and 2006 genotypic datasets have been separately analyzed in previous papers [22, 36], and the 2007 Q. agrifolia dataset is now included for this paper. We assigned maternal sources to seeds with parentage analysis, using the R script WHYP [60], matching embryo and pericarp genotypes against candidate adult trees [39, 61]. Straight-line linear distances between granaries and source trees were calculated and mapped for spatial analyses in GIS.

Heterogeneous dispersal distances

Foraging distances are strongly skewed in this system, with a heavy preponderance of very short distances and very few long distance events (see Figure 1). We used a Mann–Whitney-Wilcoxon (MWW) test, converting raw distance values into ranked values to assess the difference in cumulative ranks under null-hypothesis (no median difference) assumption (See Appendix A in Additional file 1). Denoting the sum of n 02 (distance) ranks for Q. lobata acorns in 2002 as R 02 and the corresponding sum of n 04 ranks in 2004 as R 04, we computed a pair of scaled criteria, U 02 = [R 02 – (0.5) ∙ n 02 ∙ (n 02 + 1)] and U 04 = [R 04 – (0.5) ∙ n 04 ∙ (n 04 + 1)] for Q. lobata; in similar fashion, we computed U 06 = [R 06 – (0.5) ∙ n 06 ∙ (n 06 + 1)] and U 07 = [R 07 – (0.5) ∙ n 07 ∙ (n 07 + 1)] for Q. agrifolia. Using these U-criteria, we constructed scaled measures of ranked distances for good and poor acorn crop years,

for Q. lobata and Q. agrifolia, respectively, with (Z 04–02 = −Z 02–04) and (Z 07–06 = −Z 06–07). By construction, the null hypothesis of equal distance distributions in good and poor years is tantamount to (Z 02–04 = 0 = Z 04–02) and (Z 06–07 = 0 = Z 07–06) for the two species. For the alternative hypothesis, each of the Z-criteria can range over [−1, +1], with either extreme indicating no overlap in the rank distributions for the two years under consideration. We assessed statistical support via permutation of distance ranks between the two yearly strata, (2002 and 2004) for Q. lobata, and (2006 and 2007) for Q. agrifolia, using R [62]. To reflect the strong territorial integrity of acorn woodpecker foraging, we shuffled ranks strictly within each granary, but then obtained a weighted average test of the “pooled within-granary” OFT hypothesis (see Appendix B in Additional file 1).

Diversity analysis

Following Scofield et al. [39], we define maternal source diversity within the g th granary as

where x gk is the number of acorns from oak source tree (k) found within granary (g), and n g is the total number of acorns sampled from that granary. We compute the average within-granary source diversity as the un-weighted average of the α g –values for all G granaries for that oak, species and year. The total (γ) diversity for that oak species and year was defined as

where X k is the total number of acorns sampled from the k th source tree for that species of oak and that year, across all granaries sampled.

We have deployed a [0,1]-scaled measure of source tree divergence among granaries for a single year, which (for a given species of oak and a single year) was calculated as

with the cross-granary source-sharing between the g th and h th granaries (r gh ) calculated as

Scofield et al. [39] also provide tests of whether the average (α) and (γ) values for major sampling strata, here years or oak species, are divergent, based on non-parametric Bartlett’s tests of variance homogeneity, and we have deployed those here for statistical evaluation [60].

Availability of supporting data

The data sets supporting the results of this article are available in the Data Dryad Repository (Thompson et al. 2014, http://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.64jk6). Adult genotypes and pericarps for the Q. lobata data set, and the 2006 Q. agrifolia data set, are available on the Data Dryad Repository [63, 64].

Abbreviations

- OFT:

-

Optimal foraging theory.

References

Emlen JM: Role of time and energy in food preference. Am Nat 1966, 100:611–617.

MacArthur RH, Pianka ER: On optimal use of a patchy environment. Am Nat 1966, 100:603–609.

Pyke GH, Pulliam HR, Charnov EL: Optimal foraging - selective review of theory and tests. Q Rev Biol 1977, 52:137–154.

Schoener TW: Theory of feeding strategies. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 1971, 2:369–404.

Charnov EL: Optimal foraging, marginal value theorem. Theor Popul Biol 1976, 9:129–136.

Orians GH, Pearson NE: On the theory of central place foraging. Anal Ecol Syst 1979, 155:177.

Andersson M: Optimal foraging area - size and allocation of search effort. Theor Popul Biol 1978, 13:397–409.

Brown JL, Gordon HO: Spacing patterns in mobile animals. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 1970, 1:239–262.

Schoener TW: Generality of the size-distance relation in models of optimal feeding. Am Nat 1979, 114:902–914.

Cortes MC, Uriarte M: Integrating frugivory and animal movement: a review of the evidence and implications for scaling seed dispersal. Biol Rev 2013, 88:255–272.

Carlo TA, Morales JM: Inequalities in fruit-removal and seed dispersal: consequences of bird behaviour, neighbourhood density and landscape aggregation. J Ecol 2008, 96:609–618.

Herrera JM, Morales JM, Garcia D: Differential effects of fruit availability and habitat cover for frugivore-mediated seed dispersal in a heterogeneous landscape. J Ecol 2011, 99:1100–1107.

Emsens W-J, Suselbeek L, Hirsch BT, Kays R, Winkelhagen AJS, Jansen PA: Effects of food availability on space and refuge use by a neotropical scatterhoarding rodent. Biotropica 2013, 45:88–93.

Real LA: Animal choice behavior and the evolution of cognitive architecture. Science 1991, 253:980–986.

Stephens DW: On economically tracking a variable environment. Theor Popul Biol 1987, 32:15–25.

Stephens DW: Variance and the value of information. Am Nat 1989, 134:128–140.

Caraco T: On foraging time allocation in a stochastic environment. Ecology 1980, 61:119–128.

Wunderle JM, Obrien TG: Risk-aversion in hand-reared bananaquits. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 1985, 17:371–380.

Spiegel O, Harel R, Getz W, Nathan R: Mixed strategies of griffon vultures’ ( Gyps fulvus ) response to food deprivation lead to a hump-shaped movement pattern. Mov Ecol 2013, 1:1–12.

Barnard CJ, Brown CAJ, Houston AI, McNamara JM: Risk-sensitive foraging in common shrews - an interruption model and the effects of mean and variance in reward rate. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 1985, 18:139–146.

Cartar RV: A test of risk-sensitive foraging in wild bumble bees. Ecology 1991, 72:888–895.

Scofield DG, Sork VL, Smouse PE: Influence of acorn woodpecker social behaviour on transport of coast live oak ( Quercus agrifolia Née) acorns in a southern California oak savanna. J Ecol 2010, 98:561–572.

Adler FR, Gordon DM: Optimization, conflict, and nonoverlapping foraging ranges in ants. Am Nat 2003, 162:529–543.

Hegner RE, Emlen ST: Territorial organization of the white fronted bee-eater in Kenya. Etholog 1987, 76:189–222.

Kacelnik A, Houston AI, Krebs JR: Optimal foraging and territorial defense in the great tit ( Parus major ). Behav Ecol Sociobiol 1981, 8:35–40.

Schoener TW: Simple models of optimal feeding-territory size: a reconciliation. Am Nat 1983, 121:608–629.

Franzblau MA, Collins JP: Test of a hypothesis of territory regulation in an insectivorous bird by experimentally increasing prey abundance. Oecologia 1980, 46:164–170.

Myers JP, Connors PG, Pitelka FA: Territory size in wintering sanderlings - effects of prey abundance and intruder density. Auk 1979, 96:551–561.

Bernstein RA: Foraging strategies of ants in response to variable food density. Ecology 1975, 56:213–219.

Koenig WD, McEntee JP, Walters EL: Acorn harvesting by acorn woodpeckers: annual variation and comparison with genetic estimates. Evol Ecol Res 2008, 10:811–822.

Yu HUI, Nason JD, Ge X, Zeng J: Slatkinís Paradox: when direct observation and realized gene flow disagree. A case study in Ficus. Mol Ecol 2010, 19:4441–4453.

Hirsch B, Kays R, Jansen P: A telemetric thread tag for tracking seed dispersal by scatter-hoarding rodents. Plant Ecol 2012, 213:933–943.

Carlo TA, Tewksbury JJ, del Rio CM: A new method to track seed dispersal and recruitment using N-15 isotope enrichment. Ecology 2009, 90:3516–3525.

Jansen PA, Hirsch BT, Emsens WJ, Zamora-Gutierrez V, Wikelski M, Kays R: Thieving rodents as substitute dispersers of megafaunal seeds. P Natl Acad Sci USA 2012, 109:12610–12615.

Godoy JA, Jordano P: Seed dispersal by animals: exact identification of source trees with endocarp DNA microsatellites. Mol Ecol 2001, 10:2275–2283.

Grivet D, Smouse PE, Sork VL: A novel approach to an old problem: tracking dispersed seeds. Mol Ecol 2005, 14:3585–3595.

Karubian J, Sork VL, Roorda T, Duraes R, Smith TB: Destination-based seed dispersal homogenizes genetic structure of a tropical palm. Mol Ecol 2010, 19:1745–1753.

Hardesty BD, Hubbell SP, Bermingham E: Genetic evidence of frequent long-distance recruitment in a vertebrate-dispersed tree. Ecol Lett 2006, 9:516–525.

Scofield DG, Smouse PE, Karubian J, Sork VL: Use of alpha, beta, and gamma diversity measures to characterize seed dispersal by animals. Am Nat 2012, 180:719–732.

Scofield DG, Alfaro VR, Sork VL, Grivet D, Martinez E, Papp J, Pluess AR, Koenig WD, Smouse PE: Foraging patterns of acorn woodpeckers ( Melanerpes formicivorus ) on valley oak ( Quercus lobata Née) in two California oak savanna-woodlands. Oecologia 2011, 166:187–196.

Hannon SJ, Mumme RL, Koenig WD, Spon S, Pitelka FA: Poor acorn crop, dominance, and decline in numbers of acorn woodpeckers. J Anim Ecol 1987, 56:197–207.

Koenig WD, Mumme RL: Population ecology of the cooperatively breeding acorn woodpecker. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton Univ Pr; 1987.

Winterhalder B: Opportunity-cost foraging models for stationary and mobile predators. Am Nat 1983, 122:73–84.

Koenig WD, Benedict LS: Size, insect parasitism, and energetic value of acorns stored by acorn woodpeckers. Condor 2002, 104:539–547.

Irons DB: Foraging area fidelity of individual seabirds in relation to tidal cycles and flock feeding. Ecology 1998, 79:647–655.

Mehlum F, Watanuki Y, Takahashi A: Diving behaviour and foraging habitats of Brunnich’s guillemots ( Uria lomvia ) breeding in the High-Arctic. J Zool 2001, 255:413–423.

Kotzerka J, Hatch SA, Garthe S: Evidence for foraging-site fidelity and individual foraging behavior of pelagic cormorants rearing chicks in the Gulf of Alaska. Condor 2011, 113:80–88.

Sharp WM, Sprague VG: Flowering and fruiting in white oaks: pistillate flowering, acorn development, weather and yields. Ecology 1967, 48:243–251.

Sork VL, Bramble J, Sexton O: Ecology of mast-fruiting in 3 species of North American deciduous oaks. Ecology 1993, 74:528–541.

Koenig WD, Mumme RL, Carmen WJ, Stanback MT: Acorn production by oaks in central coastal California: variation within and among years. Ecology 1994, 75:99–109.

Polansky L, Douglas-Hamilton I, Wittemyer G: Using diel movement behavior to infer foraging strategies related to ecological and social factors in elephants. Mov Ecol 2013, 1:1–11.

Grivet D, Robledo-Arnuncio JJ, Smouse PE, Sork VL: Relative contribution of contemporary pollen and seed dispersal to the effective parental size of seedling population of California valley oak ( Quercus lobata Née). Mol Ecol 2009, 18:3967–3979.

Austerlitz F, Dutech C, Smouse PE, Davis F, Sork VL: Estimating anisotropic pollen dispersal: a case study in Quercus lobata Née. Heredity 2007, 99:193–204.

Dutech C, Sork VL, Irwin AJ, Smouse PE, Davis FW: Gene flow and fine-scale genetic structure in a wind-pollinated tree species Quercus lobata Née (Fagaceaee). Am J Bot 2005, 92:252–261.

Pluess AR, Sork VL, Dolan B, Davis FW, Grivet D, Merg K, Papp J, Smouse PE: Short distance pollen movement in a wind-pollinated tree, Quercus lobata Née (Fagaceae). Forest Ecol Manag 2009, 258:735–744.

Sork VL, Davis FW, Smouse PE, Apsit VJ, Dyer RJ, Fernandez JF, Kuhn B: Pollen movement in declining populations of California Valley oak, Quercus lobata Née: where have all the fathers gone? Mol Ecol 2002, 11:1657–1668.

MacRoberts MH, MacRoberts BR: Social organization and behavior of the acorn woodpecker in central coastal California. Ornithological Monographs 1976, 21:1–115.

Koenig WD, Faeth SH: Effects of storage on tannin and protein content of cached acorns. Southwest Nat 1998, 43:170–175.

The California Acorn Survey. http://www.nbb.cornell.edu/wkoenig/wicker/CalAcornSurvey.html

Dispersal Diversity: Statistics and Tests. https://www.eeb.ucla.edu/Faculty/Sork/Sorklab/software_pmi.html

Smouse PE, Sork VL, Scofield DG, Grivet D: Using seedling and pericarp tissues to determine maternal parentage of dispersed valley oak recruits. J Hered 2012, 103:250–259.

R Core Team: R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2013. URLhttp://www.R-project.org/

Scofield DG, Smouse PE, Karubian J, Sork VL: Data from: Use of alpha, beta, and gamma diversity measures to characterize seed dispersal by animals. Dryad Digital Repository 2012. doi:10.5061/dryad.40kq7

Smouse PE, Sork VL, Scofield DG, Grivet D: Data from: Using seedling and pericarp tissues to determine maternal parentage of dispersed valley oak recruits. Dryad Digital Repository 2012. doi:10.5061/dryad.4bm3739j

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to D. Grivet who helped establish the research project on acorn movement in valley oak, and to the technicians and students who helped gather and genotype data across the years. We also thank Walt Koenig for supplying the acorn count data. Fieldwork for this study was performed at the University of California Natural Reserve System Sedgwick Reserve, administered by the University of California, Santa Barbara. We thank the Sedgwick Reserve Directors, M. Allen and K. McCurdy, and other staff for their logistical support. PGT was supported by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Science to Achieve Results (STAR) program (FP-91724501). PES was supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF-DEB-0514956), and US Department of Agriculture and New Jersey Agriculture Experiment Station (USDA/NJAES-17111). PFT and DGS received support from UCLA research award to VLS. National Science Foundation (NSF-DEB-0516529) provided support to VLS, including a post-doctoral award to DGS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

PGT ran the WHYP analysis, analyzed distance and diversity data, and led manuscript preparation. PES co-developed research goals and study design for the multi-year project, developed new statistical tools, and participated in manuscript preparation. DGS developed and coded statistical tools, conducted fieldwork and genotyping for 2006–7, and participated in data analysis and manuscript preparation. VLS co-designed research goals and sampling design of the multi-year project, conducted and managed fieldwork, oversaw genotyping across years, helped analyze data, and participated in manuscript preparation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Thompson, P.G., Smouse, P.E., Scofield, D.G. et al. What seeds tell us about birds: a multi-year analysis of acorn woodpecker foraging movements. Mov Ecol 2, 12 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/2051-3933-2-12

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/2051-3933-2-12