Abstract

Background

Opportunistic fungi are dispersed as airborne, ground and decaying matter. The second most frequent extra-pulmonary disease by Aspergillus is in the central nervous system.

Case presentation

The case subject was 55 years old, male, mulatto, and an assistant surveyor residing in Teresina, Piauí. He presented with headache, seizures, confusion, fever and left hemiparesis upon hospitalization in 2006 at Hospital São Marcos. Five years previously, he was diagnosed with diabetes mellitus, and 17 months previously he had acne margined by hyperpigmented areas and was diagnosed with leprosy. Laboratory tests indicated leukocytosis and magnetic resonance imaging showed an infarction in the right cerebral hemisphere. Cerebrospinal fluid examination showed 120 cells/mm3 and was alcohol-resistant bacilli negative. Trans-sphenoidal surgery with biopsy showed inflammation was caused by infection with Aspergillus fumigatus. We initiated use of parenteral amphotericin B, but his condition worsened. He underwent another surgery to implant a reservoir of Ommaya–Hickmann, a subcutaneous catheter. We started liposomal amphotericin B 5 mg/kg in the reservoir on alternate days. He was discharged with a prescription of tegretol and fluconazole.

Conclusion

This report has scientific interest because of the occurrence of angioinvasive cerebral aspergillosis in a diabetic patient, which is rarely reported. In conclusion, we suggest a definitive diagnosis of cerebral aspergillosis should not postpone quick effective treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Opportunistic fungi are dispersed in nature as airborne particles from soil and mulch [1, 2] and infection results from aspiration of conidia in the air, especially in humid environments [3]. Aspergillus fumigatus, Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus niger species account for 95% of infections in humans [4]. Aspergillus infection becomes more important in immunocompromised patients, such as transplanted patients, human immunodeficiency virus carriers and patients undergoing cancer treatment [5]. The most common type of infection is invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (80–90%) that can spread to the central nervous system (CNS) in 10–25% of cases. The second most common extra-pulmonary disease is that of the CNS [6].

The fungus can reach the brain through the blood by contiguity through the cribriform walls of the sphenoid sinus and cavernous sinus, optic nerve or vascular walls, or by direct implantation through neurosurgery [3]. The most common characteristic clinical symptoms of infection are headache, altered mental status and seizures [7]. Patients may manifest seizures or focal neurological signs from mass effect or stroke [8]. Diagnostics are performed by imaging and fungus can be measured in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) using Sabouraud agar with culture medium [4, 9]. Surgical treatment should be early and aggressive with the purpose of eliminating most of the necrotic material via sinus surgery or craniotomy [10].

Case presentation

This paper presents a case report of invasive aspergillosis of the CNS with mycotic carotid arteritis. Early diagnosis and appropriate treatment are essential for a good prognosis.

The case subject was a 55-year-old male, mulatto, who was an assistant surveyor residing in Teresina (PI). Five years previously, he was diagnosed with diabetes mellitus and started on treatment with neutral protamine hagedorn (NPH) insulin + metformin. During this period, the patient had one episode of decreased level of consciousness.

Seventeen months previously, he presented with margined hyperpigmented dermatosis and was diagnosed with leprosy. He started treatment with dapsone for 14 months. He reported headaches six months ago, initially related to sinusitis treated by an otolaryngologist, but then started having seizures and was transferred to a neurologist who initiated anticonvulsants. The patient was not involved in gardening or agricultural activities and he was not a smoker. The patient worked as an assistant surveyor in the measurement of land, which could cause potential exposure to fungi from the air and soil.

Three months previously, he developed mental confusion, fever and left hemiparesis, and was admitted to São Marcos Hospital on 2 March 2006. He was prescribed NPH insulin, metformin 850 mg, rocefin 2 g/day, meticorten, tegretol 600 mg/day and gardenal 100 mg/day.

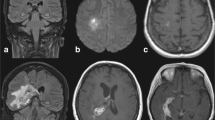

Laboratory and imaging tests were conducted. The hemogram on 2 March 2006 showed leukocytosis was 10.300 cells/mm3, 0.7 mg% creatinine and glucose 160 mg%. Chest X-ray showed pleural thickening with obliteration of the left costophrenic sinus on 4 March 2006. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) on 9 March 2006 showed right cerebral hemisphere infarction with hyperemia luxury, thrombosis of the carotid artery and sphenoid expansive process with cavernous sinus invasion, meningeal base and hydrocephalus (Figure 1). Lumbar puncture was performed with CSF examination (14 March 2006), which showed 120 cells/mm3, 69% lymphocytes, 49 mg% protein and 87 mg% glucose with negative alcohol resistant bacilli (BAAR) in the CSF.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging in T1-weighted series of (A) axial, (B) coronal, and (C) sagittal sections. The hyperintense areas in topography of the right sphenoid sinus are evident in the three images, suggestive of fungal sinusitis. Hyperintense areas in the right superolateral cortical regions are evident in the three images, suggestive of cerebral infarction with luxury hyperemia by arteritis.

After examination, the patient was transferred from the clinical neurologist to a neurosurgeon, otolaryngologist and infectologist. He underwent trans-sphenoidal surgery with biopsy on 4 March 2006, which showed inflammation and intense infection by Aspergillus fumigatus by hematoxylin-eosin staining of biopsy samples (Figure 2).

Parenteral liposomal amphotericin B (5 mg/kg/day) treatment was initiated but there was worsening of symptoms with a decreased level of consciousness after intensification of convulsive seizures and vomiting. Liposomal amphotericin B is an alternative for the treatment of choice in some cases. Here, liposomal amphotericin B was initiated because of its lower cost compared to voriconazole.

A second surgery was performed on 17 May 2006 to implant a subcutaneous Ommaya - Hickmann reservoir and intra-ventricular catheter. Ventricular CSF was collected and examination showed 820 cells/mm3, 58% neutrophils, 106 mg% protein and 31 mg% glucose, with negative culture.

A new cranial CT scan showed right cerebral hemisphere infarction, and a catheter was placed into the right lateral ventricle and there was a reduction of hydrocephalus. Liposomal amphotericin B 5 mg/kg by reservoir on alternate days was initiated while maintaining NPH parenteral insulin and tegretol l.600 mg/day. The Infectious Diseases Society (IDSA) guidelines recommend 3–5 mg/kg/day of liposomal amphotericin B for treatment of cerebral aspergillosis. The scheme was administered on alternate days because of the patient’s clinical condition and comorbidities.

The galactomannan test was not performed. Diagnosis of fungal infection was made by histopathology. Histopathological sections obtained by sphenoid biopsy demonstrated the presence of septate hyphae with dichotomous branching, suggesting Aspergillus spp.

There was progressive clinical improvement, seizures stopped, and the patient awoke, could feed orally and walk, with support, with reduced left hemiparesis. The patient was discharged on 14 June 2006 with a prescription of 600 mg/day tegretol + 150 mg fluconazol 2 capsules/day.

Discussion

Aspergillus dissemination to the CNS is a devastating complication of invasive aspergillosis [11–13]. CNS aspergillosis is the most lethal manifestation of Aspergillus infection with a mortality rate of > 90% [12].

Aspergillus infection often occurs in patients with weakened immune systems, such as transplant patients, HIV carriers and patients undergoing cancer treatment [14]. Other factors of immunosuppression include diabetes mellitus and leprosy, comorbidities previously shown by case reports [15]. Although people have contact with a variety of species of Aspergillus, only seven species are implicated in human infections. Aspergillus fumigatus is responsible for about 90% of infections, followed by Aspergillus flavus [16].

The main route of contamination of the CNS is hematogenous dissemination and contiguity from an adjacent area, such as the orbit or paranasal sinuses [10, 17, 18]. The hyphae may block intracerebral blood vessels, promote infarction that is commonly hemorrhagic and sterile, and can progress to a septic abscess [9, 14, 19–22] that promotes mixed inflammation reactions, necrosis [21, 22], vasculitis and mycotic aneurysms [9, 20, 22].

There have been few reports of invasive cerebral aspergillosis in patients with diabetes [23], indicating the relevance of this study as the patient had diabetes mellitus and leprosy as factors impairing the immune system. Oddo and Acuña [24], in a study of 5,612 necropsies, found 175 cases of opportunistic infection, and aspergillosis totaled 41 cases (23.4%) ranking second, behind candidiasis.

Clinical manifestations result from the fungus pathogenicity and the host immune response [25]. The presence of seizures confirms the case reported by Nogales-Gaete et al. [3]. The diagnosis of aspergillosis is difficult and complex because of its nonspecific signs and symptoms [26], and is performed by imaging tests that show changes that must then be correlated with clinical, histopathological and laboratory tests (culture and serology).

Early diagnosis is very important for the management of mold infections of the CNS to allow for timely therapeutic intervention and prevention of neurologic sequelae. CT and MRI are important adjuncts in the detection of infection and in monitoring the course of therapy [27].

Detection of galactomannan antigen and 1,3-β-dglucan in CSF can assist in the diagnosis of cerebral aspergillosis and other mold infections [28, 29]. However, as these antigens can also be produced by other species of fungi such as Fusarium, Scedosporium and Exserohilum rostratum, the detection of these antigens do not provide definitive diagnosis of cerebral aspergillosis [30]. A polymerase-chain-reaction assay specific for aspergillus might be useful, but standardized platforms are lacking [31].

There have been few randomized trials on the treatment of invasive aspergillosis. Most observations of treatment of CNS aspergillosis are based on open-label studies. One randomized trial for invasive aspergillosis demonstrated a trend toward improvement of CNS aspergillosis in patients treated with voriconazole [32].

Itraconazole, posaconazole, or liposomal amphotericin B are recommended for patients who are intolerant or refractory to voriconazole. Among the amphotericins, liposomal amphotericin B showed favorable responses in some case reports [33–35], in agreement with the current study.

Nabika et al. [36] reported that surgical reduction of aspergilloma combined with local administration of antifungal was a good treatment option, corroborating the present study. According to Pianetti et al. [25], fungal infections observed as a mass should be treated by aggressive surgical resection. A patient with recurrence may benefit from the application of intralesional amphotericin B [37]. There have been few descriptions of patients with cerebral aspergillosis that survived after undergoing surgery and antifungal therapy [20, 22].

Conclusion

This report has scientific interest because of the occurrence of angioinvasive cerebral aspergillosis in a diabetic patient, findings that are rare in the literature. In conclusion, a definitive diagnosis of cerebral aspergillosis should not postpone treatment.

Consent

This study was approved by the Ethics and Research of the University Hospital of the Federal University of Maranhão (233/09). The Statement of Informed Consent Form was presented to the patient and signed in accordance with Resolution No. 196/96. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this Case Report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Abbreviations

- CNS:

-

Central nervous system

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- CSF:

-

Cerebrospinal fluid

- NPH:

-

Neutral protamine hagedorn

- BAAR:

-

Alcohol resistant bacilli

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- IDSA:

-

Infectious diseases society.

References

De Hoog GS, Josep G, Figueras MJ: Atlas dos Fungos Clínica. 2000, Utrecht, Holanda: Voor Centraalbureau Schimmelcultures, 1: 2ª

Richardson MD, Johnson EM: Fungal infection. Opportunistic Fungal Infections. 2000, Malden, MA: [S.l.]: Blackwell. Science, 30-36. [Pubmed]

Nogales-Gaete J, Navarrete C, González J, Sáez D, Quijada M, Espinoza L: Aspergilosis meningovascular: Caso clínico. Rev Chil Neuro-Psiquiatr. 2005, 43 (3): 217-225.

del Palácio A, Cuétara MS, Pontón J: El diagnóstico de laboratorio de La aspergilosis invasora. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2003, 20 (2): 90-98.

Amromin GD, Gildenhorn VB: Massive cerebral Aspergillus abscess in a leukemic child. J Neurosurg. 1971, 35 (4): 491-494. 10.3171/jns.1971.35.4.0491.

Borges Sá M, Liebana-Fiederling A: Clinical presentations of nosocomial aspergillosis. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2000, 17 (3): S85-S89.

Azarpira N, Esfandiari M, Bagheri MH, Rakei S, Salari S: Cerebral aspergillosis presenting as a mass lesion. Braz J Infect Dis. 2008, 12 (4): 349-351.

Segal BH: Aspergillosis. N Engl J Med. 2009, 360: 1870-1884. 10.1056/NEJMra0808853.

Grossman RI, Davis KR, Taveras JM, Beal MF, O’Carrol CP: Computed tomography in intracranial aspergillosis. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1981, 5 (1): 646-650.

Camarata PJ, Dunn DL, Farney AC, Parker RG, Seljeskog EL: Continual intracavitary administration of amphotericin B as an adjunct in the treatment of aspergillus brain abscess: case report and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 1992, 31: 575-579. 10.1227/00006123-199209000-00023.

Patterson TF, Kirkpatrick WR, White M, Hiemenz JW, Wingard JR, Dupont B, Rinaldi MG, Stevens DA, Graybill JR: Invasive aspergillosis: disease spectrum, treatment practices, and outcomes. I3 Aspergillus Study Group. Medicine (Baltimore). 2000, 79: 250-260. 10.1097/00005792-200007000-00006.

Walsh TJ, Hier DB, Caplan LR: Aspergillosis of the central nervoussystem: clinicopathological analysis of 17 patients. Ann Neurol. 1985, 18: 574-582. 10.1002/ana.410180511.

Lin SJ, Schranz J, Teutsch SM: Aspergillosis case-fatality rate: systematic review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2001, 32: 358-366. 10.1086/318483.

Aschdown BC, Tien RD, Felsberg GJ: Aspergilosis of the brain and paranasal sinuses in imminocompromised patients: CT and MRI imaging findings. Am J Roentgenol. 1992, 162: 155-159.

De Franco MF, Irina K: Ficomicose órbito-rino-cerebral associada à cetoacidose diabética: Registro de um caso. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1970, 12 (5): 354-363.

Miglets AW, Saunders WH, Leona A: Aspergillosis of the sphenoid sinus. Arch Otolaryngol. 1978, 104: 47-50. 10.1001/archotol.1978.00790010051011.

Denning DW: Invasive aspergillosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1998, 26: 781-805. 10.1086/513943.

Wiles CM, Kocen RS, Symon L, Scaravilli F: Aspergillus granuloma of the trigeminal ganglion. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1981, 44 (5): 451-455. 10.1136/jnnp.44.5.451.

Enzmann DR, Brant-Zawadzki M, Britt RH: CT of central nervous system infections in immunocompromised patient. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1980, 135 (2): 263-267. 10.2214/ajr.135.2.263.

Miaux Y, Ribaud P, Williams M, Guermazi A, Gluckman E, Brocheriou C, Laval-Jeantet M: MR of cerebral aspergillosis in patients who have had a bone marrow transplantation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1995, 16 (3): 555-562.

Beal MF, O’Carrol CP, Kleinman GM, Grossman RI: Aspergillosis of the nervous system. Neurology. 1982, 32: 473-479. 10.1212/WNL.32.5.473.

Sharma RR, Gurusinghr NT, Lynch PG: Cerebral infarction due to aspergillus arterits following glioma surgery. Br J Neurosurg. 1992, 6: 485-490. 10.3109/02688699208995040.

Norlinah MI, Ngow HA, Hamidon BB: Angioinvasive cerebral aspergillosis presenting as acute ischaemic stroke in a patient with diabetes mellitus. Singapore Med J. 2007, 48 (1): e1-e4.

Oddo D, Acuña G: Opportunistic infections in Chilean autopsy cases, 1960–1986. Bull Pan Am Health Organ. 1982, 22: 17-26.

Pianetti Filho G, Pedroso ERP, Gianetti AV, Darwich R: Aspergilose Cerebral Em Paciente Imunocompetente. Arq Neuro-Psiquiatr. 2005, 63 (4): 1094-1098. 10.1590/S0004-282X2005000600033.

Lyons RW, Andriole VT: Fungal infection of CNS. Neurol Clin. 1986, 4: 159-170.

McCarthy M, Rosengart A, Schuetz AN, Kontoyiannis DP, Walsh TJ: Mold infections of the central nervous system. N Engl J Med. 2014, 371: 150-160. 10.1056/NEJMra1216008.

Soeffker G, Wichmann D, Loderstaedt U, Sobottka I, Deuse T, Kluge S: Aspergillus galactomannan antigen for diagnosis and treatment monitoring in cerebral aspergillosis. Prog Transplant. 2013, 23: 71-74. 10.7182/pit2013386.

Mikulska M, Furfaro E, Del Bono V, Raiola AM, Di Grazia C, Bacigalupo A, Viscoli C: (1–3)-β-D-glucan in cerebrospinal fluid is useful for the diagnosis of central nervous system fungal infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2013, 56: 1511-1512. 10.1093/cid/cit073.

Tortorano AM, Esposto MC, Prigitano A, Grancini A, Ossis C, Cavanna C, Cascio GL: Cross-reactivity of Fusarium spp. in the Aspergillus galactomannan enzymelinked immunosorbent assay. J Clin Microbiol. 2012, 50: 1051-1053. 10.1128/JCM.05946-11.

Reinwald M, Buchheidt D, Hummel M, Duerken M, Bertz H, Schwerdtfeger R, Reuter S, Kiehl MG, Barreto-Miranda M, Hofmann WK, Spiess B: Diagnostic performance of an Aspergillus-specific nested PCR assay in cerebrospinal fluid samples of immunocompromised patients for detection of central nervous system aspergillosis. PLoS One. 2013, 8 (2): e56706-10.1371/journal.pone.0056706.

Herbrecht R, Denning DW, Patterson TF, Bennett JE, Greene RE, Oestmann JW, Kern WV, Marr KA, Ribaud P, Lortholary O, Sylvester R, Rubin RH M, Wingard JR, Stark P, Durand C, Caillot D, Thiel E, Pranatharthi HC, Hodges MR, Schlamm HT, Troke PF, Pauw B: Voriconazole versus amphotericin B for primary therapy of invasive aspergillosis. N Engl J Med. 2002, 347: 408-415. 10.1056/NEJMoa020191.

Ng A, Gadong N, Kelsey A, Denning DW, Leggate J, Eden OB: Successful treatment of Aspergillus brain abscess in a child with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2000, 17: 497-504. 10.1080/08880010050120863.

Khoury H, Adkins D, Miller G, Goodnough L, Brown R, DiPersio J: Resolution of invasive central nervous system aspergillosis in a transplant recipient. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1997, 20: 179-180. 10.1038/sj.bmt.1700852.

Coleman J, Hogg G, Rosenfeld J, Waters K: Invasive central nervous system aspergillosis: cure with liposomal amphotericin B, itraconazole, and radical surgery—case report and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 1995, 36: 858-863. 10.1227/00006123-199504000-00032.

Nabika S, Kiya K, Satoh H, Mizoue T, Araki H, Oshita J: Local administration of amphotericin B against aspergilloma in the prepontine cistern–case report. Neurol Med Chir. 2007, 47 (2): 89-92. 10.2176/nmc.47.89.

Epstein NE, Hollingsworth R, Black K, Framer P: Fungal brain abscess (aspergillosis/mucormycosis) in two immunosuppressed patients. Surg Neurol. 1991, 35: 286-289. 10.1016/0090-3019(91)90006-U.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Hospital São Marcos, Teresina-PI for the availability of medical records.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JBAS and MDSBN participated in interpretation of data, and drafted and critically revised the manuscript. JBAS and MDSBN contributed to study design, interpretation of data, and critically revised the manuscript. MACNS and WEMF analyzed and assisted in interpretation of the data and assisted in drafting the manuscript. GFBB and GMCV contributed to interpretation of data and critically revised the manuscript. JBAS assisted in data acquisition and interpretation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Segundo, J.B.A., da Silva, M.A.C.N., Filho, W.E.M. et al. Cerebral aspergillosis in a patient with leprosy and diabetes: a case report. BMC Res Notes 7, 689 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-7-689

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-7-689