Abstract

Background

Central nervous system involvement is considered a rare complication of chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and so there is the risk of being overlooked.

Case presentation

We report a case of central nervous system involvement in a 75-year-old mulatto woman with chronic lymphocytic leukemia after 5 years of follow-up and a literature review on the subject. The clinical course, treatment and outcome are described. A systematic, meticulous and comprehensive analysis of existing publications regarding chronic lymphocytic leukemia with central nervous system involvement was performed.

Conclusion

We concluded that central nervous system involvement of chronic lymphocytic leukemia is probably not associated with any evident risk factors. Diagnostic approach differs by institutions but often includes imaging, morphology and flow cytometry. Resolution of central nervous system symptoms can usually be accomplished with intrathecal chemotherapy or irradiation followed by systemic treatment. The recognition of this entity by clinicians could lead to early detection and treatment, resulting in better outcomes in this rare complication.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL) occurs in elderly patients and is characterized by proliferation and accumulation of monoclonal B lymphocytes, expressing CD5, CD20 and CD23 molecules [1, 2]. The involvement of central nervous system (CNS) is considered a rare and aggressive complication. Nevertheless, autopsy studies suggest that it is much more common than supposed in clinical practice [3–5]. Reske-Nielsen and co-workers (1974) were one of the first groups to detect this CNS infiltration. These authors observed neurologic infiltration in 10 advanced stage patients, in a total of 14 CLL necropsies. However, none of them had any neurologic symptoms [6].

In most studies, case presentations are presented [7–10] whereas others emphasize the role of diagnostic methods [11, 12]. Our aim is to present a new case of CLL with leptomeningeal involvement and also to make a review of the literature, focusing studies where immunophenotypic profile was performed.

Case presentation

A 75-year-old mulatto woman was admitted to the University Hospital with a 2-week history of headache, otalgia in the right ear, fever, dizziness and dysphagia. Physical examination showed diffuse lymphadenopathy, gait instability, peripheral right-side facial nerve palsy and incoordination of lower limbs. Muscle strength and reflexes were normal in the upper limbs. Her medical history was remarkable for hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), diagnosed five years earlier (Rai stage I with evolution to Rai II with lymphocyte increasing and response to treatment). She was no longer receiving treatment for this disorder and the last chemotherapy had occurred five months before. She had been treated before in three occasions, with clorambucil and prednisone, due to lymphocytosis and liver and spleen enlargement, from June to Sep 2005 (4 cycles) from Oct 2006 to June 2007 (8 cycles) and from June 2008 to August 2009 (14 cycles).

Peripheral blood evaluation revealed leucocytosis (white blood cell – WBC = 24.3×109/L), a mild anemia (hemoglobin = 10.5 g/L) and 123×109 platelets/L, and immunophenotypic study confirmed B-CLL. On the biochemical examination, normal values of serum bilirubin, amylase, BUN, uric acid, albumin, transaminases, calcium, potassium and iron were observed. As neurological examination had suggested a possible left brain ischemia, computed tomography (CT) scan of the brain was performed, but it was within normal limits. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was recommended, but the patient refused to do it because of claustrophobia. Upper endoscopy was normal. Acute otitis media was treated by myringotomy (showed serosanguineous fluid) with clavulin and acyclovir.

An immediate lumbar puncture was performed and the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) revealed WBC count of 18 leukocytes/mm3 (mononuclear cells: 80%; polimorphonuclear neutrophils: 20%), glucose of 92 mg/dL and total protein of 50 mg/dL. GRAM, BAAR and criptococcal were negative; bacteria, mycobacteria and fungi cultures; and herpes virus in polymerase chain reaction (PCR)/cryptococcal antigens were negative, VDRL and TPHA negatives. Cytological examination of liquor showed typical and immunophenotypic analysis revealed small and monomorphic lymphocytes subset with profile: CD19+, CD5low and lambda+, confirming CLL in CSF (Figure 1).

Cerebrospinal fluid and peripheral blood immunophenotyping: flow cytometric dot plots of cerebrospinal fluid (A, C and D) and peripheral blood (B) demonstrating CLL populations. The units on the x- and y-axes are fluorescent intensitity. (A and B) CD5 XCD19 in cerebrospinal fluid and peripheral blood cells, respectively. Four colour cytometry was performed using FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences) flow cytometry. The minority of cerebrospinal fluid cells were positive to double staining showing in circle of the panel A. Panel C shows monoclonality to Ig lambda.

There was complete resolution of neurological symptoms liquor infiltration after 6 doses of weekly intrathecal methotrexate and systemic fludarabine plus cyclophosphamide treatment. She was outpatient followed but died nine months after, due to sepsis. Autopsy was not done.

Review of the literature of CLL cases involving CNS

The review of the literature was conducted according Cochrane guidelines and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis recommendations [13, 14].

In December 13, 2013 the search was conducted in PubMed Central (National Center for Biotechnology Information, US National Library of Medicine, Washington). In order to use search terminology Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) headings was used. We conducted two search strategies.

The MeSH terms used in the database search included: Leukemia, Lymphoid/complications; Leukemia, Lymphoid/pathology; Brain Neoplasms/radiography; Leukemia, Lymphoid/physiopathology; Leukemia, Lymphocytic, Chronic, B-Cell/cerebrospinal fluid; Leukemia, Lymphocytic, Chronic, B-Cell/drug therapy; Leukemia, Lymphocytic, Chronic, B-Cell/radiotherapy; Leukemia, Lymphocytic, Chronic, B-Cell/drug therapy; Lymphoma, B-Cell/radiotherapy; Leukemia, Lymphocytic, Chronic, B-Cell/diagnosis; Central Nervous System Neoplasms/immunology.

For the second search strategy the term "Chronic lymphocytic leukemia" was used in the search titles.

Studies were selected if they met the following inclusion criteria:

-

1.

Indexed articles between January 1st 1975 and December 13th 2013;

-

2.

The search included the follow documents: letters to the editor, case presentations, case series, original research reports and reviews;

-

3.

Clinical research articles in adults;

-

4.

The following idioms were included: English, French, German and Spanish;

For exclusion criteria:

-

1.

Articles published outside of proposed period;

-

2.

Other published articles not specified by inclusion criteria;

-

3.

Experimental clinical research articles;

-

4.

Articles written by languages not specified by inclusion criteria;

-

5.

Ritcher syndrome.

Search results were merged using EndNote X7 (Thomson Reuters, TX, USA) reference manager, and duplicate records removed. The titles and abstracts of the articles were then examined and reports that were not randomized studies and those that were not relevant were removed.

All abstracts were independently reviewed by two authors, and full texts were reviewed for determining eligibility if abstracts were incomplete. Manuscripts that met inclusion criteria were retained for full analysis. Any disagreements were resolved by further discussion involving an additional author.

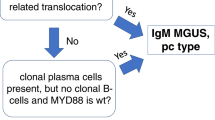

The search identified 24,367 articles, of which 4,951 were removed for being duplicated. A total of 68 articles were eligible satisfying established criteria for two research strategies [2, 5, 7–10, 15–79]. The flow diagram representing the selection studies is shown in Figure 2.

The characteristics of the 89 previous reported patients and those of the present case are summarized in Table 1. More men than women were diagnosed with CNS-CLL (male/female ratio: 1.77). The median time for CNS disease was 29.5 months (ranging from 0 to 156 months), since CLL diagnosis. Positive cytology alone, and with immunophenotyping analyses, was positive in 57 of 64 cases (89%). The majority of patients with available clinical data were treated with intrathecal chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy with systemic chemotherapy and most of them demonstrated improvement in their symptomatology. Neurological symptoms at presentation varied. Visual changes occurred in one quarter of cases, with or without other manifestations, such as slurred speech, headaches, gait disorder and memory loss.

Conclusions

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) involving the central nervous system (CNS) presents with a high clinical heterogeneity [80]. Some patients experiment a real indolent course and have life expectancy similar to unaffected individuals, while others have an aggressive malignancy that requires early treatment and have limited survival. As the disease progresses, lymphocytes infiltrate lymph nodes, spleen and liver [81–83]. Occasionally, these cells can infiltrate other organs, such as skin [84], lungs, pleura, [85], gonads, prostate [86], kidneys [87] and gastrointestinal tract [88]. Ratterman and colleagues (2014) described in a recent systematic review about extramedullary CLL, that CNS and skin were the most frequently affected sites [81].

Including the present case, 92 patients have been described with CNS-CLL in this review, and it provides the largest summary of patients previously reported. Corroborating other authors’ results, the current analysis suggests that CNS-CLL is not as unusual as it seems [2, 80, 81]. Nevertheless, CNS-CLL may be neglected for several reasons, leading to improper and under-reported diagnosis. Moreover, other neurological manifestations, including opportunistic infections, secondary brain malignancies, therapy-related neurotoxicity, metabolic encephalopathies and paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes, were described in this entity [80]. Given the paucity of reports describing central nervous system (CNS) involvement, large scale investigations are complex and challenging to perform and, consequently, the appropriate identification and management of this disease are hampered.

For the diagnosis evaluation, three parameters are routinely used: (a) clinical signs and symptoms, (b) radiological imaging, (c) cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis. Clinical manifestations ranged from the absence of neurological signs, as described in autopsy series [5, 89], to a diverse and non-specific spectrum of symptoms (Table 1), which are common in this age group. Dementia, gait disturbance, hearing loss and other neurologic symptoms are present in many diseases found in senescence. Studies attempting to identify risk factors in patients who develop CNS infiltration have failed in detecting common predisposing conditions. A relevant number of patients had the CNS involvement confirmation at the same time of chronic lymphocytic leukemia diagnosis. In addition to these in vivo findings, autopsy studies confirm that many patients who had CNS involvement never referred neurological symptoms [3–6].

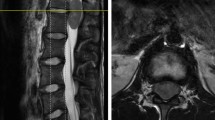

Radiologic findings (computed tomography [CT] and magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) of CNS involvement have been described as diffuse coating of the leptomeninges by a thin layer of leukemic cells, nodule growths, plaque-like deposits and intraparenchymal infiltration [2, 79]. However, cranial imaging has low sensibility in detecting intracranial CLL, in comparison with other diseases [90] and low specificity, as it may be misdiagnosed with meningioma [15]. The present review confirms previous studies, in which imaging investigation detected CNS infiltration in approximately 40% of CLL cases [2, 80]. Besides, in 4 cases of CSF negative for CLL infiltration, radiologic imaging revealed brain masses [16–19].

Regarding the CSF analysis, the sample is obtained by lumbar puncture and all precautions must be taken in order to minimize contamination by peripheral blood. This evaluation includes global and specific cell count, glucose, total protein, culture and cytology. Although CSF cytology examination is considered the “gold standard” for diagnoses, due to its excellent specificity (>95%), its sensibility is within 50% to 60% [91].

Several variables associated with false negative cytology have been identified [92], mainly due to the paucity of tumor cells in CSF. Also, CLL lymphocytes can not be distinguished from reactive lymphocytes by morphology alone [93]. Reactive lymphocytes may be common in these patients, who present immune suppression and are susceptible to opportunistic infections.

Flow cytometry immunophenotyping (FCI) is an objective and rapid method for qualitative and quantitative analysis of cell suspensions. It can detect small populations of tumor cells with aberrant surface-marker expression, through multicolor and multiparameter analysis. FCI is considered to be two to three times more sensitive than cytology in detecting CSF malignant infiltration [2, 11, 12, 80, 92, 94–96]. It is particularly helpful for the detection of clonal populations of small sized B lymphocytes [97] which would lead to the indication intrathecal chemotherapy and or radiotherapy. The sensitivity of this technique can be enhanced by cytocentrifuge methods as described by Akintola-Ogunremi and coworkers (2002) [7].

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) also known to improve sensitivity in detecting CSF malignancy. However, PCR assay requires more time than FCI, and needs the selection of specific tumor cell primers. Therefore its routine employment continues to be restricted [98]. Vogt-Schaden and colleagues (1999) confirmed leptomeningeal dissemination in a patient with CLL using a clone-specific CDR3 region in IgH encoding locus. It has already been reported in a study about lymphomas and reactive lymphoid proliferations that the use of both FCI and PCR techniques in different sample specimens [77]. The authors observed a superior sensitivity of FCM when compared with PCR (77% vs 64%). However, they concluded that combined use should be considered as the sensitivity reached to 93% [99].

The identification of specific tumor markers for CNS leukemic invasion has remained elusive. Soluble CD27 (sCD27) was already considered a probable marker for leptomeningeal involvement. Van den Bent and coworkers (2002) [100] demonstrated that it was useful in ruling out the disease with a negative predictive value of 92%. Nevertheless sCD27 was also detected in various non-malignant inflammatory conditions (positive predictive value = 54%).

Although larger prospective studies with longer follow-up are required, we suggest that patients should be carefully evaluated for more precise evidence of CNS lymphoid malignancies before receiving toxic treatments. In addition mentioning Pirandello’s masterpiece “So It Is (If You Think So)” clinicians should use all possible diagnostic tools to identify CNS infiltration in CLL. After this systematic review, we can conclude that the early identification of the central nervous system involvement and prompt treatment should be considered to reduce morbidity and improve quality of life of these patients.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this Case presentation and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Abbreviations

- B-CLL:

-

B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- CD:

-

Cluster of differentiation

- CNS:

-

Central nervous system

- WBC:

-

White blood cell

- BUN:

-

Blood urea nitrogen

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- CSF:

-

Cerebrospinal fluid

- FCI:

-

Flow cytometry immunophenotyping

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- sCD27:

-

Soluble CD27.

References

Matutes E, Attygalle A, Wotherspoon A, Catovsky D: Diagnostic issues in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL). Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2010, 23: 3-20.

Moazzam AA, Drappatz J, Kim RY, Kesari S: Chronic lymphocytic leukemia with central nervous system involvement: report of two cases with a comprehensive literature review. J Neurooncol. 2012, 106: 185-200.

Bojsen-Moller M, Nielsen JL: CNS involvement in leukaemia. An autopsy study of 100 consecutive patients. Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Scand A. 1983, 91: 209-216.

Barcos M, Lane W, Gomez GA, Han T, Freeman A, Preisler H, Henderson E: An autopsy study of 1206 acute and chronic leukemias (1958 to 1982). Cancer. 1987, 60: 827-837.

Cramer SC, Glaspy JA, Efird JT, Louis DN: Chronic lymphocytic leukemia and the central nervous system: a clinical and pathological study. Neurology. 1996, 46: 19-25.

Reske-Nielsen E, Petersen JH, Sogaard H, Jensen KB: Leukaemia of the central nervous system. Lancet. 1974, 1: 211-212.

Akintola-Ogunremi O, Whitney C, Mathur SC, Finch CN: Chronic lymphocytic leukemia presenting with symptomatic central nervous system involvement. Ann Hematol. 2002, 81: 402-404.

Imitola J, Pitt K, Peoples JL, Krynska B, Sheikh H, Kesari S, Azizi SA: Multifocal CNS infiltration of chronic lymphocytic leukemia in the form of small-cell solid metastatic lesions. J Neurooncol. 2012, 109: 213-215.

Cohen JB, Cavaliere R, Byrd JC, Andritsos LA: Hearing loss due to infiltration of the tympanic membrane by chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Case Rep Hematol. 2012, 2012: 589718-

Benjamini O, Jain P, Schlette E, Sciffman JS, Estrov Z, Keating M: Chronic lymphocytic leukemia with central nervous system involvement: a high-risk disease?. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2013, 13: 338-341.

Nowakowski GS, Call TG, Morice WG, Kurtin PJ, Cook RJ, Zent CS: Clinical significance of monoclonal B cells in cerebrospinal fluid. Cytometry B Clin Cytom. 2005, 63: 23-27.

Bommer M, Nagy A, Schöpflin C, Pauls S, Ringhoffer M, Schmid M: Cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis: pitfalls and benefits of combined analysis using cytomorphology and flow cytometry. Cancer Cytopathol. 2011, 119: 20-26.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group: Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009, 339: 332-336.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, Mike C, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D: The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009, 339: b2700-

Kelly K, Lynch K, Farrell M, Rawluk D, Kaliaperumal C, Murphy P: Intracranial small lymphocytic lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2008, 141: 411-

Nimubona S, Bernard M, Morice P, Brassier G, Caulet-Maugendre S, Carsin B, Meunier C, Lamy T: Complications of malignancy: case 3. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia presenting with panhypopituitarism. J Clin Oncol. 2004, 22: 374-376.

Kiewe P, Dallenbach FE, Fischer L, Hoecht S, Kombos T, Thiel E, Korfel A: Isolated B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder at the dura mater with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia immunophenotype. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma. 2007, 7: 594-596.

Denier C, Tertian G, Ribrag V, Lozeron P, Bilhou-Nabera C, Lazure T, Abbed K, Lacroix C, Adams D: Multifocal deficits due to leukemic meningoradiculitis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Neurol Sci. 2009, 277: 130-132.

Kakimoto T, Nakazato T, Hayashi R, Hayashi H, Hayashi N, Ishiyama T, Asada H, Ishida A: Bilateral occipital lobe invasion in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2010, 28: e30-e32.

Amiel JL, Droz JP: Letter: spinal lymphocytosis during chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Nouv Presse Med. 1976, 5: 94-95.

Boogerd W, Vroom TM: Meningeal involvement as the initial symptom of B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Eur Neurol. 1986, 25: 461-464.

Brick WG, Majmundar M, Hendricks LK, Kallab AM, Burgess RE, Jillella AP: Leukemic leptomeningeal involvement in Stage 0 and Stage 1 chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia Lymphoma. 2002, 43: 199-201.

Calvo-Villas JM, Fernández JA, de la Fuente I, Godoy AC, Mateos MC, Poderós C: Intrathecal liposomal cytarabine for treatment of leptomeningeal involvement in transformed (Richter’s syndrome) and non-transformed B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukaemia in Spain: a report of seven cases. Br J Haematol. 2010, 150: 618-620.

Cash J, Fehir KM, Pollack MS: Meningeal involvement in early stage chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer. 1987, 59: 798-800.

Conesa V, Mompel A, Ruiz J, Gómez A, Fernandez P, Lucas J, Aranda I: Fulminant brain lymphoid infiltration in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Am J Hematol. 1999, 60: 167-168.

Currie JN, Lessell S, Lessell IM, Weiss JS, Albert DM, Benson EM: Optic neuropathy in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Arch Ophthalmol. 1988, 106: 654-660.

Diwan RV, Diwan VG, Bellon EM: Brain involvement in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1982, 6 (4): 812-814.

Elliott MA, Letendre L, Li CY, Hoyer JD, Hammack JE: Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia with symptomatic diffuse central nervous system infiltration responding to therapy with systemic fludarabine. Br J Haematol. 1999, 104: 689-694.

Estevez M, Chu C, Pless M: Small B-cell lymphoma presenting as diffuse dural thickening with cranial neuropathies. J Neurooncol. 2002, 59: 243-247.

Fain JS, Naeim F, Becker DP, Van Herle A, Yan-Go F, Petrus L, Vinters HV: Chronic lymphocytic leukemia presenting as a pituitary mass lesion. Can J Neurol Sci. 1992, 19: 239-242.

Fernández P, Ordónez FS, Dominguez AR, Rodriguez AS: Infiltration of the central nervous system as a presentation form of early stage chronic lymphocyte leukemia. Am J Hematol. 1998, 58: 339-342.

Garicochea B, Cliquet MG, Melo N, del Giglio A, Dorlhiac-Llacer PE, Chamone DA: Leptomeningeal involvement in chronic lymphocytic leukemia identified by polymerase chain reaction in stored slides: a case presentation. Mod Pathol. 1997, 10: 500-503.

Garofalo M, Murali R, Halperin I, Magardician K, Moussouris HF, Masdeu JC: Chronic lymphocytic leukemia with hypothalamic invasion. Cancer. 1989, 64: 1714-1716.

Getaz EP, Miller GJ: Spinal cord involvement in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer. 1979, 43: 1858-1861.

Giordano A, Perrone T, Guarini A, Ciappetta P, Rubini G, Ricco R, Palma M, Specchia G, Liso V: Primary intracranial dural B cell small lymphocytic lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007, 48: 1437-1443.

Gobbi M, Tazzari PL, Raspadori D, Cavo M, Pileri S, Tura S: Meningeal leukemia complicating prolymphocytoid transformation of B-chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Acta Haematol. 1985, 74 (4): 205-207.

Grisold W, Jellinger K, Lutz D: Human neurolymphomatosis in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Clin Neuropathol. 1990, 9: 224-230.

Hagberg H, Lannemyr O, Acosta S, Birgegård G, Hagberg H: Successful treatment of syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic secretion (SIADH) in 2 patients with CNS involvement of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Eur J Haematol. 1997, 58: 207-208.

Hanse MC, Van't Veer MB, van Lom K, van den Bent MJ: Incidence of central nervous system involvement in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and outcome to treatment. J Neurol. 2008, 255: 828-830.

Hoffman MA, Valderrama E, Fuchs A, Friedman M, Rai K: Leukemic meningitis in B-cell prolymphocytic leukemia. A clinical, pathologic, and ultrastructural case study and a review of the literature. Cancer. 1995, 75: 1100-1103.

Kaiser U: Cerebral involvement as the initial manifestation of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Acta Haematol. 2003, 109: 193-195.

Kalac M, Suvic-Krizanic V, Ostojic S, Kardum-Skelin I, Barsic B, Jaksica B: Central nervous system involvement of previously undiagnosed chronic lymphocytic leukemia in a patient with neuroborreliosis. Int J Hematol. 2007, 85: 323-325.

Knop S, Herrlinger U, Ernemann U, Kanz L, Hebart H: Fludarabine may induce durable remission in patients with leptomeningeal involvement of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2005, 46: 1593-1598.

Korsager S, Laursen B, Munck Mortensen T: Dementia and central nervous system involvement in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Scand J Haematol. 1982, 29: 283-286.

Kuwabara H, Kanamori H, Takasaki H, Takabayashi M, Yamaji S, Tomita N, Fujimaki K, Fujisawa S, Ishigatsubo Y: Involvement of central nervous system in prolymphocytoid transformation of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2003, 44: 1235-1237.

Lange CP, Brouwer RE, Brooimans R, Vecht CJ: Leptomeningeal disease in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2007, 109: 896-901.

Liepman MK, Votaw ML: Meningeal leukemia complicating chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer. 1981, 47: 2482-2484.

López Guillermo A, Cervantes F, Bladé J, Matutes E, Urbano A, Montserrat E, Rozman C: Central nervous system involvement demonstrated by immunological study in prolymphocytic variant of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Acta Haematol. 1989, 81: 109-111.

Lustman F, Flament-Durant J, Colle H, Lambert M, Sztern B: Paraplegia due to epidural infiltration in a case of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Neurooncol. 1988, 6: 259-260.

Majumdar G: Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia with cerebral infiltration. Leuk Lymphoma. 1998, 28: 603-605.

Marmont AM: Leukemic meningitis in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia: resolution following intrathecal methotrexate. Blood. 2000, 96: 776-777.

Michalevicz R, Burstein A, Razon N, Reider I, Ilie B: Spinal epidural compression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer. 1989, 64: 1961-1964.

Michallet M, Socié G, Mohty M, Sobh M, Bay JO, Morisset S, Labussière-Wallet H, Tabrizi R, Milpied N, Bordigoni P, El-Cheikh J, Blaise D: Rituximab, fludarabine, and total body irradiation as conditioning regimen before allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for advanced chronic lymphocytic leukemia: long-term prospective multicenter study. Exp Hematol. 2013, 41: 127-133.

Miller K, Budke H, Orazi A: Leukemic meningitis complicating early stage chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1997, 121: 524-547.

Morrison C, Shah S, Flinn IW: Leptomeningeal involvement in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer Pract. 1998, 6: 223-228.

Mowatt L, Matthews T, Anderson I: Sustained visual recovery after treatment with intrathecal methotrexate in a case of optic neuropathy caused by chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Neuroophthalmol. 2005, 25: 113-115.

Nemoto K, Ohnishi Y, Tsukada T: Chronic lymphocytic leukemia showing pituitary tumor with massive leukemic cell infiltration, and special reference to clinicopathological findings of CLL. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1978, 28: 797-805.

Pastor E, Grau E, Real E: Leukemic meningitis in a patient with B-cell prolymphocytic leukemia. Haematologica. 1997, 82: 511-512.

Patton WN, Carey MP, Fletcher MR, Rolfe EB, Spooner D, Richardson PR, Franklin IM: Diffuse intracerebral involvement in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a case presentation. Clin Lab Haematol. 1992, 14: 149-154.

Pohar S, de Metz C, Poppema S, Hugh J: Chronic lymphocytic leukemia with CNS involvement. J Neurooncol. 1993, 16: 35-37.

Poplawska-Szczyglowska L, Walewski J, Pienkowska-Grela B, Rymkiewicz G, Mioduszewska O: Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia presenting with central nervous system involvement. Med Oncol. 1999, 16: 65-68.

Remkova A, Bezayova T, Vyskocil M: B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia with meningeal infiltration by T lymphocytes. Eur J Int Med. 2003, 14: 49-52.

Rubin P, Harris NL: Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital: case 4. A 73-year-old man with severe facial pain, visual loss, decreased ocular motility, and an orbital mass. N Engl J Med. 1993, 328: 266-275.

Ruiz P, Moezzi M, Chamizo W, Ganjei P, Whitcomb CC, Rey LC: Central nervous system expression of a monoclonal paraprotein in a chronic lymphocytic leukemia patient. Acta Haematol. 1992, 88: 37-40.

Russwurm G, Heinsch M, Radkowski R, Erlemann R, Aul C, Haase S, Giagounidis A: Dasatinib induces complete remission in a patient with primary cerebral involvement of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia failing chemotherapy. Blood. 2010, 116: 2617-2618.

Rye AD, Stitson RN, Dyer MJ: Pituitary infiltration in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2001, 115: 718-

Sáenz-Francés F, Calvo-González C, Reche-Frutos J, Donate-López J, Huelga-Zapico E, García-Sánchez J, García-Feijoó J: Bilateral papilledema secondary to chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2007, 82: 303-306.

Schmidt-Hieber M, Thiel E, Keilholz U: Spinal paraparesis due to leukemic meningitis in early-stage chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2005, 46: 619-621.

Singh AK, Thompson RP: Leukaemic meningitis in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Acta Haematol. 1986, 75: 113-115.

Solal-Celigny P, Schuller E, Courouble Y, Gislon J, Elghozi D, Boivin P: Cerebromeningeal location of chronic lymphoid leukemia. Rapid immunochemical diagnosis and complete remission by intrathecal chemotherapy. Presse Med. 1983, 12: 2323-2325.

Spectre G, Gural A, Amir G, Lossos A, Siegal T, Paltiel O: Central nervous system involvement in indolent lymphomas. Ann Oncol. 2005, 16: 450-454.

Stagg MP, Gumbart CH: Chronic lymphocytic leukemic meningitis as a cause of the syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone. Cancer. 1987, 60: 191-192.

Steinberg JP, Pecora M, Lokey JL: Leukemic meningitis in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer Treat Rep. 1985, 69: 687-688.

Thiruvengadam R, Bernstein ZP: Central nervous system involvement in prolymphocytic transformation of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Acta Haematol. 1992, 87: 163-164.

Tonino SH, Rijssenbeek AL, Oud ME, Pals ST, van Oers MH, Kater AP: Intracerebral infiltration as the unique cause of the clinical presentation of chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2011, 29: e837-e839.

Treppendahl MB, Andersen N, Jurlander J, Geisler C: A case of chronic lymphocytic leukemia with deletion 17p and bilateral retinal leukemic infiltrates. Eur J Haematol. 2009, 82: 79-80.

Vogt-Schaden M, Wildemann B, Stelljes M, Haas J, Storch-Hagenlocher B, Grond-Ginsbach C: Leptomeningeal dissemination of chronic lymphatic leukemia. Molecular genetic detection in cerebrospinal fluid. Nervenarzt. 1999, 70: 363-367.

Wang ML, Shih LY, Dunn P, Kuo MC: Meningeal involvement in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia: report of two cases. J Formos Med Assoc. 2000, 99: 775-778.

Watanabe N, Takahashi T, Sugimoto N, Tanaka Y, Kurata M, Matsushita A, Maeda A, Nagai K, Nasu K: Excellent response of chemotherapy- resistant B-cell-type chronic lymphocytic leukemia with meningeal involvement to rituximab. Int J Clin Oncol. 2005, 10: 357-361.

Lopes da Silva R: Spectrum of neurologic complications in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2012, 12: 164-179.

Ratterman M, Kruczek K, Sulo S, Shanafelt TD, Kay NE, Nabhan C: Extramedullary chronic lymphocytic leukemia: systematic analysis of cases reported between 1975 and 2012. Leuk Res. 2014, 38: 299-303.

Rai KR, Sawitsky A, Cronkite EP, Chanana AD, Levy RN, Pasternack BS: Clinical staging of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 1975, 46: 219-234.

Binet JL, Auquier A, Dighiero G, Chastang C, Piguet H, Goasguen J, Vaugier G, Potron G, Colona P, Oberling F, Thomas M, Tchernia G, Jacquillat C, Boivin P, Lesty C, Duault MT, Monconduit M, Belabbes S, Gremy F: A new prognostic classification of chronic lymphocytic leukemia derived from a multivariate survival analysis. Cancer. 1981, 48: 198-206.

Robak E, Robak T: Skin lesions in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007, 48: 855-865.

Moore W, Baram D, Hu Y: Pulmonary infiltration from chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Thorac Imaging. 2006, 21: 172-175.

D'Arena G, Guariglia R, Villani O, Martorelli MC, Pietrantuono G, Mansueto G, Patitucci G, Imbriani E, Masciandaro T, Borgia L, Vita G, D'Auria F, Statuto T, Musto P: An urologic face of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: sequential prostatic and penis localization. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2013, 5: e2013008-

Uprety D, Peterson A, Shah BK: Renal failure secondary to leukemic infiltration of kidneys in CLL–a case presentation and review of literature. Ann Hematol. 2013, 92: 271-273.

Malhotra P, Singh M, Kochhar R, Nada R, Wig JD, Varma N, Varma S: Leukemia infiltration of bowel in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005, 62: 614-615.

Bower JH, Hammack JE, McDonnell SK, Tefferi A: The neurologic complications of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Neurology. 1997, 48: 407-412.

Lee SH, Hur J, Kim YJ, Lee HJ, Hong YJ, Choi BW: Additional value of dual-energy CT to differentiate between benign and malignant mediastinal tumors: an initial experience. Eur J Radiol. 2013, 82: 2043-2049.

Glantz MJ, Cole BF, Glantz LK, Cobb J, Mills P, Lekos A, Walters BC, Recht LD: Cerebrospinal fluid cytology in patients with cancer: minimizing false-negative results. Cancer. 1998, 82: 733-739.

Gold DR, Nadel RE, Vangelakos CG, Davis MJ, Livingston MY, Heath JE, Reich SG, Gojo I, Morales RE, Weiner WJ: Pearls and oy-sters: the utility of cytology and flow cytometry in the diagnosis of leptomeningeal leukemia. Neurology. 2013, 80: e156-e159.

Hegde U, Filie A, Little RF, Janik JE, Grant N, Steinberg SM, Dunleavy K, Jaffe ES, Abati A, Stetler-Stevenson M, Wilson WH: High incidence of occult leptomeningeal disease detected by flow cytometry in newly diagnosed aggressive B-cell lymphomas at risk for central nervous system involvement: the role of flow cytometry versus cytology. Blood. 2005, 105: 496-502.

Bromberg JE, Breems DA, Kraan J, Bikker G, van der Holt B, Smitt PS, van den Bent MJ, van't Veer M, Gratama JW: CSF flow cytometry greatly improves diagnostic accuracy in CNS hematologic malignancies. Neurology. 2007, 68: 1674-1679.

Schroers R, Baraniskin A, Heute C, Vorgerd M, Brunn A, Kuhnhenn J, Kowoll A, Alekseyev A, Schmiegel W, Schlegel U, Deckert M, Pels H: Diagnosis of leptomeningeal disease in diffuse large B-cell lymphomas of the central nervous system by flow cytometry and cytopathology. Eur J Haematol. 2010, 85: 520-528.

Ahluwalia MS, Wallace PK, Peereboom DM: Flow cytometry as a diagnostic tool in lymphomatous or leukemic meningitis: ready for prime time?. Cancer. 2012, 118: 1747-1753.

French CA, Dorfman DM, Shaheen G, Cibas ES: Diagnosing lymphoproliferativ disorders involving the cerebrospinal fluid: increased sensitivity using flow cytometric analysis. Diagn Cytopathol. 2000, 23: 369-374.

Rhodes CH, Glantz MJ, Glantz L, Lekos A, Sorenson GD, Honsinger C, Levy NB: A comparison of polymerase chain reaction examination of cerebrospinal fluid andconventional cytology in the diagnosis of lymphomatous meningitis. Cancer. 1996, 77: 543-548.

Davidson B, Risberg B, Berner A, Smeland EB, Torlakovic E: Evaluation of lymphoid cell populations in cytology specimens using flow cytometry and polymerase chain reaction. Diagn Mol Pathol. 1999, 8: 183-188.

van den Bent MJ, Lamers CH, van 't Veer MB, Sillevis Smitt PA, Bolhuis RL, Gratama JW: Increased levels of soluble CD27 in the cerebrospinal fluid are not diagnostic for leptomeningeal involvement by lymphoid malignancies. Ann Hematol. 2002, 81: 187-191.

Acknowledgements

We thank the following agencies: FAPERJ, CAPES and UERJ for their financial support and Ji Hyun Paschall for English revision.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SLS and FS conceived the study, collected the data and drafted the manuscript. MMR-C and ARS helped in analysis and interpretation of data. AA and MHO revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. MMR-C helped in drafting the manuscript. MHO did the critical analyses and corrections. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

de Souza, S.L., Santiago, F., Ribeiro-Carvalho, M.d.M. et al. Leptomeningeal involvement in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a case report and review of the literature. BMC Res Notes 7, 645 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-7-645

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-7-645