Abstract

Background

The shape of the appendicular bones in mammals usually reflects adaptations towards different locomotor abilities. However, other aspects such as body size and phylogeny also play an important role in shaping bone design.

We used 3D landmark-based geometric morphometrics to analyse the shape of the hind limb bones (i.e., femur, tibia, and pelvic girdle bones) of living and extinct terrestrial carnivorans (Mammalia, Carnivora) to quantitatively investigate the influence of body size, phylogeny, and locomotor behaviour in shaping the morphology of these bones. We also investigated the main patterns of morphological variation within a phylogenetic context.

Results

Size and phylogeny strongly influence the shape of the hind limb bones. In contrast, adaptations towards different modes of locomotion seem to have little influence. Principal Components Analysis and the study of phylomorphospaces suggest that the main source of variation in bone shape is a gradient of slenderness-robustness.

Conclusion

The shape of the hind limb bones is strongly influenced by body size and phylogeny, but not to a similar degree by locomotor behaviour. The slender-robust “morphological bipolarity” found in bone shape variability is probably related to a trade-off between maintaining energetic efficiency and withstanding resistance to stresses. The balance involved in this trade-off impedes the evolution of high phenotypic variability. In fact, both morphological extremes (slender/robust) are adaptive in different selective contexts and lead to a convergence in shape among taxa with extremely different ecologies but with similar biomechanical demands. Strikingly, this “one-to-many mapping” pattern of evolution between morphology and ecology in hind limb bones is in complete contrast to the “many-to-one mapping” pattern found in the evolution of carnivoran skull shape. The results suggest that there are more constraints in the evolution of the shape of the appendicular skeleton than in that of skull shape because of the strong biomechanical constraints imposed by terrestrial locomotion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

One of the key aspects of species biology is locomotion, which determines many important behavioural activities such as foraging, hunting, escaping from predators, or migrating [1–3]. Therefore, the study of locomotor adaptations in living and extinct species is crucial to understanding their role in present and past ecosystems [4, 5].

Natural selection has led to morphological adaptations in the postcranial skeleton, which have been largely treated in the literature as “ecomorphological indicators” of locomotion modes in living species. Thus, several studies on locomotor evolution in mammals have used limb indicators of ecological adaptations to determine paleobiological aspects in extinct species [6–14]. However, natural selection is not always the only factor in shaping morphological traits [15–17]. It is important to investigate the effects of different potential sources of variation prior to identifying possible ecomorphological correlates, such as phylogenetic inheritance [15–17] or allometry [18–23].

This study investigated the influence of phylogeny, allometry, and locomotor behaviour in shaping the morphology of the hind limb bones (i.e., femur, tibia, and pelvic girdle bones) in mammalian carnivores (extant and extinct taxa from the order Carnivora plus some taxa from the closely-related order Creodonta). We used mammalian fissiped carnivorans (i.e., a paraphyletic group that includes members of the mammalian order Carnivora exclusive of members of the clade Pinnipedia, which were excluded due to their highly aquatic specialization) as a model system for the following reasons: (i) their mode of locomotion is remarkably diverse, including arboreal, terrestrial, and semiaquatic modes [24–28]; (ii) they have a different hunting styles, including pursuing, pouncing, ambushing, or hunting [9, 29–36]; and (iii) their phylogenetic relationships are well characterised [37].

This article forms part of a wider study on the ecomorphology and evolution of the appendicular skeleton in the order Carnivora with a particular focus on the influence of various factors in shaping the fore- and hind limb bones. We complement the analysis of the forelimb [38] by studying the evolution of the hind limb. This study will therefore lead to a complete picture of the morphological evolution of all major limb bones of the carnivoran appendicular skeleton as a whole.

Our predictive hypothesis was that there would be many similarities between the evolution of the bone shape of the fore- and hind limbs. However, as these limbs have several functional differences and anatomical peculiarities, we also predicted that there would be some differences in their patterns of evolution. For example, it has been demonstrated that the forelimbs of domestic dogs support a greater proportion of body weight than the hind limbs [39, 40] and this could be the case for all fissiped carnivorans. If this supposition were correct, it would be reasonable to assume that allometry has less effect on the hind limb bones than on the forelimb bones. Furthermore, hind limbs are thought to be more important in providing impulse during acceleration and running than the forelimbs [39, 41, 42] and therefore locomotor behaviour could have a stronger influence on shaping the hind limb than the forelimb. On the other hand, many carnivoran species use their forelimbs for activities other than the ones involved in locomotion, such as grasping, climbing, or manipulating prey [28, 33, 43] and this could also be a potential source of morphological differences between the fore- and hind limbs.

We used 3D geometric morphometrics to characterize the morphology of the hind limb bones (i.e., femur, tibia and the pelvic girdle bones) in order to answer the following questions: i) Is there an allometric effect in shaping the morphology of the hind limb bones; (ii) Is there a phylogenetic signal in all hind limb bones? (iii) Is there an association between locomotor behaviour and the shape of these bones? (iv) What are the evolutionary pathways followed by the hind limb long bones? (v) Is the evolutionary pattern of the hind limb similar to that of the forelimb? (vi) Does the appendicular skeleton – fore- and hind limbs – reflect functional and ecological convergences similar to the way the craniodental skeleton reflects them?

Results

Phylogeny and size

The permutation tests performed to investigate the presence of a phylogenetic structure in shape (Procrustes coordinates, Pco) and size (Log-transformed centroid size, Log-Cs) showed statistically significant results for all the bones (Table 1). The multivariate regressions of shape on size were statistically significant in all cases and indicate the presence of interspecific allometry (Figure 1A, 1C and 1E). The shape changes explained by interspecific allometry are shown in Figure 1B, 1D, and 1F (also see Additional file 1).The multivariate regressions between the phylogenetic independent contrasts for shape on the contrasts for size also yielded significant results and suggest that allometry is not merely due to a phylogenetic effect (Figure 2A, 2C, and 2E). The shape changes explained by evolutionary allometry are shown in Figure 2B, 2D, and 2F.

Analysis of interspecific allometry. Bivariate graphs derived from the multivariate regressions performed from the Pco against the Log-Cs for the pelvis (A), femur (C), and tibia (E). The three-dimensional models showing the associated size-related shape change (SRSC) for the pelvis (B [lateral view]), femur (D [caudal view]) and tibia (F [caudal and lateral views]) are also shown. Symbols: red squares, Ailuridae; green squares, Amphicyonidae; black stars, Barbourofelidae; black circles, Canidae; empty stars, Creodonta; red circles, Felidae; yellow triangles, Hyaenidae; blue triangles, Mustelidae; green triangles, Nimravidae; yellow circles, Procyonidae; blue squares, Ursidae. See Additional file 3: Table S1 for the species labels. For the interactive three-dimensional shape models explained by size variation see Additional file 1.

Analysis of evolutionary allometry. Bivariate graphs derived from the multivariate regressions performed from the contrasted Pco against the Log-CS, which has been adjusted through phylogenetic independent contrasts analysis, for pelvis (A), femur (C), and tibia (E). The three-dimensional models showing the size-related shape change (SRSC) for the pelvis (B [lateral view]), femur (D [caudal view]) and tibia (F [lateral view]) are also shown.

Phenotypic spaces and their histories of occupation

Principal component analyses (PCA) were performed to investigate the morphological variability of each bone and their respective phylomorphospaces (Figure 3). The PCA performed on the shape of the pelvis (although we only analyzed one side of the pelvic girdle [innominate bone], we refer to it as the pelvic girdle or pelvis for easier understanding) provided two principal components (PC), which accounted for more than 52% of the original variance. The first PC (Figure 3A, x axis) differentiated the pelvis of hyaenids and ursids with positive scores from the shape of the pelvis of felids with negative scores. The second PC (Figure 3A, y axis) mainly differentiated musteloids (i.e., procyonids, ailurids, and mustelids) with positive scores from canids and hyaenids with negative scores. The corresponding shapes at the extremes of both eigenvectors are shown in Figure 3B and Additional file 2A.A visual inspection of this phylomorphospace shows that the terminal branches are relatively short and the internal branches are relatively long (Figure 3A). This pattern suggests that the pelvis shapes of closely related species are similar. This result was confirmed by the reconstruction of the pelvis shapes for the basal nodes of each family (Figure 4A) and shows that each family has a well-defined characteristic morphology.

Principal component analyses. Bivariate graph derived from PC I and PC II with the regression residuals (Pco-Cs) for the pelvis (A), femur (C), and tibia (E). The plots also show the tree topology mapped on the morphospace. Three-dimensional models showing the shape change associated with these axes for the pelvis (B [lateral view]), femur (D [caudal and lateral views]), and tibia (F [caudal and proximal views]). Blue empty circle: tree root; see Figure 3 for more symbols. See Additional file 2 for interactive models. See Additional file 3: Table S1 for species labels.

The PCA performed on the shape of the femur yielded two significant PCs, which together explained around 52% of the original variance. The first PC (Figure 3C, x axis) mainly differentiated the extinct creodont Patriofelis, the ursids Ailuropoda melanoleuca and Ursus spelaeus, and the “false saber-tooth” Barbourofelis with negative scores from most canine canids. The maned wolf (Chrysocyon brachyurus) had extreme positive scores. In contrast, the second PC (Figure 3C, y axis) differentiated the species into a gradient that starts at the femur of Eira barbara (within mustelids), felids, and procyonids with positive scores and ends at the femur of Lontra canadensis with extreme negative scores. The corresponding shapes at the extremes of these eigenvectors are shown in Figure 3D and Additional file 2B.

The PCA performed on the shape of the tibia gave two significant PCs, which jointly accounted for approximately 74% of the total shape variation. PC I (Figure 3E, x axis) differentiated the tibia of most canines and Acinonyx jubatus (within felids) with positive scores from the tibia of Barbourofelis, Hoplophoneus, Ursus spelaeus, and Ailuropoda melanoleuca with extreme negative scores according to a set of morphological traits (Figure 3F and Additional file 2C). However, PC II (Figure 3E, y axis) differentiated the species into a gradient that starts at the tibia of Barbourofelis and Hoplophoneus and ends at the tibia of most ursids according to the shape changes shown in Figure 3F and Additional file 2C.The phylomorphospaces of the femur and tibia are clearly different from that of the pelvis (compare Figure 3A with Figure 3C and 3E) because the phylomorphospaces of the long bones have long terminal branches and short internal ones. This suggests that some families overlap with each other, creating a “messy” pattern. In fact, the reconstruction of the basal nodes of each family for both long bones suggests that shape divergence mainly occurred within each family (Figure 4B and 4C).

Locomotor behaviour

A between-group PCA was performed for each bone to investigate the effect of locomotor behaviour on hind limb bone shapes (see Additional file 3: Table S1).

The first two PCs obtained for the pelvis explained around 54% of the total variance (Figure 5A). The first component mainly differentiated the Canadian river otter (Lontra canadensis) with positive scores from cursorial carnivores with negative scores (Figure 5A, x axis) according to a set of morphological traits (Figure 5B and Additional file 4A). However, the second component differentiated the semifossorial European badger (Meles meles) and the terrestrial giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) with positive scores from other species (Figure 5A, y axis; see Figure 5B and Additional file 4A for morphological changes). These PCs do not appear to clearly differentiate any of the other ecological groups.

Between-group principal component analyses. Bivariate graph derived from PC I and PC II with the regression residuals (Pco-Cs) for pelvis (A), femur (C), and tibia (E). The plots also show the tree topology mapped on the morphospace. Three-dimensional models showing the shape change associated with these axes for the pelvis (B [lateral view]), femur (D [caudal and lateral views]), and tibia (F [caudal and lateral views]). Symbols: blue empty circle, tree root; blue circles, cursorial; green circles, scansorial; orange triangle, terrestrial; black square, arboreal; yellow square, semiaquatic; red circle, semifossorial. See Additional file 4 for interactive models. See Additional file 3: Table S1 for species labels.

The first two PCs obtained for the femur accounted for more than 80% of the total variance (Figure 5C). The first component differentiated semiaquatic Lontra canadensis with negative scores from other species with positive scores (Figure 5C, x axis). In contrast, the second component mainly differentiated cursorial species and some terrestrial species with positive scores from scansorial species, arboreal species, and some terrestrial species with negative scores (Figure 5C, y axis). The morphological changes associated with these eigenvectors are shown in Figure 5D and Additional file 4B.

The between-group PCA performed on the tibia provided the first two PCs that accounted for around 88% of the total variance (Figure 5E). The first axis differentiated some cursorial species and some terrestrial species with positive scores from the remaining taxa (Figure 5E, x axis). The second PC mainly differentiated the semifossorial European badger plus some cursorial and terrestrial species with positive scores from other taxa (Figure 5E, y axis). The morphological changes associated with these eigenvectors are shown in Figure 5F and Additional file 4C.

Discussion

Phylogeny and allometry are significant sources of bone variation

The permutation test showed that phylogeny influences the shape and size of the hind limb bones (Table 1). These results are in line with those obtained for the forelimb bones [13, 26, 28, 38]. It appears that the shape and size of the carnivoran appendicular skeleton were acquired early during the evolution of each family and were maintained with little variation during their subsequent evolution.

The shape of the hindlimb is strongly influenced by size differences (i.e., allometry) and this association is not merely due to a phylogenetic correlation (Figures 1 and 2). Given the similarity between these results and previous findings for the forelimb bones [38], we suggest that the shape of the entire appendicular skeleton of fissiped carnivorans is strongly influenced by size differences. These results are in line with previous research on limb-bone scaling in mammals [18, 21, 44].

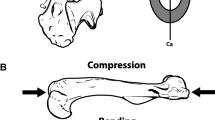

With the sole exception of the tibia, the allometric changes were related to bone robustness (Figures 1B, 1D and 2B, and 2D) and probably indicate the need of larger animals to manage increasing stresses due to their large body size [44]. However, increased bone robustness is not the only way to reduce peak stresses in large-sized animals; the adoption of a more upright posture also reduces bending stresses and increases the effective mechanical advantage of muscles [20, 45]. The size-related shape changes shown for the tibia involve an increase of shaft curvature and a change in the condyles in the proximal epiphysis to a more horizontal position (Figures 1F and 2F). These shape changes could be related to large-sized species needing to adopt a more upright posture because these changes enhance resistance to axial stresses at the expense of bending stresses [20].

The allometric changes in the hind limb bones described above are generally equivalent to those obtained for the forelimb bones shape described in Martín-Serra et al.[38].

Morphological variability and phylomorphospaces

The difference in phylogenetic conservatism between the PCA obtained for the pelvis and the PCAs obtained for the long bones are equivalent to findings obtained for the forelimb [38]. We found that the scapula was a more conservative bone than the humerus or the radius-ulna complex. This implies that the tight connection of the pelvis to the axial skeleton is not a potential cause of its phylogenetic conservatism. This is because the scapula is not directly connected to the axial skeleton and is also a highly conservative bone. Similarly, the fact that the scapula is composed mainly by a single element (as the coracoid is a small process with little relevance compared with the main body of the scapula [46]) could indicate that the more complex structure of the pelvis (formed by three different fused elements) is not a feasible explanation for its phylogenetic conservatism. In contrast, the differences between the proximal and distal elements of the limbs could be explained by their different developmental origin [47].

The first PC of the size-free shapes of the femur and tibia shows that the main axis of shape variation is a gradient of slenderness-robustness (Figure 3C and 3F). However, there are numerous morphological similarities among distantly related taxa with different ecologies. On the one hand, having slender bones is common to most canine canids, hyenids, the extinct “dog-like” bear Hemicyon, the cheetah, the bobcat, and the serval. However, having slender bones is a morphological solution, which could be favoured by natural selection for different purposes such as the active pursuit of prey (e.g., the cheetah), long-distance pursuit (e.g., wolves), or long-distance foraging (e.g., foxes). In any case, slender hind limb bones indicate cursorial adaptations, i.e., an increased capacity to run faster and/or to run for longer distances with more energetic efficiency [5, 9, 24, 48–50]. On the other hand, distantly related taxa with different ecologies also share extremely robust hind limb bones. For example, the European badger, the extinct cave bear, and some procyonids share robust femora and tibiae. This is also the case for the extinct Patriofelis (order Creodonta), the false saber-toothed cats Barbourofelis and Hoplophoneus, and the saber-tooth Smilodon. In mammalian carnivores, having robust limb bones is thought to be an adaptation in order to resist axial and bending stresses [29] related to multiple activities such as moving excavated soil during digging (e.g., the European badger) or withstanding body weight loads generated during hunting in large cats [25, 29, 33, 36, 51, 52].

In summary, several distantly related taxa adapted to different ecological habits and functional necessities share bone morphologies that involve having slender or robust limbs. We found little differentiation between the behavioural categories, which could be due to the fact that many ecological contexts could favour one solution or another.

Locomotor behaviour is only partially reflected by the shape of the hind limb bones

The six ecological groups were not clearly differentiated by the between-group PCAs performed to investigate the effects of ecology on bone shape variation. Species are differentiated according to their phylogenetic relationships. For example, bone morphology does not differentiate terrestrial canids from cursorial canids and terrestrial felids are not differentiated from scansorial felids. A visual inspection of the phylomorphospaces shows a clear phylogenetic effect in the distribution of taxa because internal branches are larger than more terminal branches (Figure 5A, 5C and 5E). These results were expected, as other authors have found that phylogeny strongly influences bone morphology and locomotor behaviour [27, 53].

Conclusions

This article has demonstrated that the shape of the hind limb bones is strongly influenced by size differences. In addition, allometric shape changes show that large-sized species have pelvises with larger areas for the attachment of proximal limb muscles. They also have more robust femora. The shape of their tibiae suggests that they have a more upright posture compared to smaller species. These allometric shape changes are not merely due to a phylogenetic pattern. Nevertheless, phylogeny and size have a strong influence on limb bone shape. Furthermore, the phenotypic spaces indicated that, once size effects are discarded, the main axis of shape variation is still a gradient of slenderness-robustness. We hypothesized that this axis reflects an adaptive trade-off between maintaining energetic efficiency during locomotion – acquired by having slender bones – and resisting high peak stresses – acquired by having robust bones. However, both morphological extremes can be adaptive in multiple ecological scenarios and behavioural contexts leading to a lack of a one-to-one correspondence between morphology and function. Thus, several species with very different ecologies have similar hind limb bone shapes, which is probably due to the presence of strong biomechanical and phylogenetic constraints that mask the association between locomotor behaviour and bone shape. In fact, we found that the ecological influence on limb bone shape was very weak when we analysed specific morphological differences between several ecological groups.

The pattern of hind limb shape evolution described in this article is equivalent to the pattern of forelimb shape evolution [38]. This tight correspondence between the fore- and hind limb in shape evolution means that future studies can investigate the patterns of morphological integration between both limbs from structural and functional perspectives. Thus, we suggest that the entire appendicular skeleton of mammalian carnivores represents a conspicuous example of a “one-to-many” pattern of evolution between phenotype and function. Strikingly, this pattern of evolution is in complete contrast to the “many-to-one” pattern for the evolution of the craniodental skeleton in which similar morphological solutions evolved multiple times in different lineages to accomplish similar functions such as feeding [54]. This suggests that the appendicular skeleton could be more constrained than the crania, probably because of the strong biomechanical constraints imposed by active locomotion.

Methods

Data

The data set included 135 pelvises, 194 femora, and 194 tibiae from 46 species of modern carnivorans and 27 extinct ones (see Additional file 3: Tables S1, S2 and S3). Modern and extinct species were selected to include the highest morphological variability within each family as far as possible. We also included Patriofelis† or Hyaenodon pervagus† (Mammalia, Creodonta) whenever possible with a similar purpose, i.e., to increase morphological variability by including an example of a closely related mammalian order, such as Creodonta [55]. Adult specimens alone were included to avoid the effects of ontogenetic variation. Adults were defined by the complete fusion of the epiphysis to the diaphysis. All the specimens were housed in the following institutions: American Museum of Natural History (AMNH, New York), Natural History Museum (NHM, London), Naturhistorisches Museum (NMB, Basel), Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales (MNCN, Madrid), Museo di Storia Naturale (MSN, Firenze), Staten Naturhistoriske Museum (SNM, Copenhagen), and Museo de Ciencias Naturales de Valencia (MCNV, Valencia).

Digitized landmarks and three-dimensional model construction

A set of three-dimensional landmarks was digitized using a Microscribe G2X. Their 3D coordinates (x,y,z) were imported into Exce using the Immersion software package (Immersion, Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). These landmarks (Figure 6) were chosen to capture the most important morphological aspects of the hind limb bones [56, 57] (Additional file 3: Table S4).

A three-dimensional analysis of hind limb evolution in carnivores. A, main bones of the hind limb analysed in this paper. B, Landmarks used in the morphometric analyses of the hind limb bones (for detailed descriptions see Additional file 3: Table S4). C, key morphological features in the carnivoran pelvis of. D, main morphological structures in the femur and tibia of carnivorans. The muscle origins (red) and insertions (purple) of the main muscles involved in locomotion are also shown for each hind limb bone. (Anatomical keys were obtained from Barone [56] and Homberger and Walker [57]).

Shape visualizations at the extremes of the multivariate axes were performed by warping the scanned surface of a Panthera onca (femur and tibia) and an Uncia uncia (pelvis), using Landmark software [58] (see [38] for further details).

We performed a Procrustes fit [59] using the landmark coordinates. To avoid the effects of static allometry, we averaged the Procrustes coordinates (Pco) and Centroid size (Cs) by species. We averaged by genus those specimens not identified at the species level (e.g., Tomarctus sp., Hoplophoneus sp.). Only in the case of Smilodon sp. we averaged by genus in order to avoid taxonomical uncertainty at the genus level. These procedures and all the following statistical analyses were performed using the MorphoJ software [60]. All these morphometric data are available in Additional file 5.

The phylogenetic signal in limb bone shape and size

Mesquite software [61] was used to construct a phylogenetic tree (Figure 7) to assess phylogenetic patterns in the sample following information in published sources. Tree topology was constructed using the trees published by Nyakatura and Bininda-Emonds [37] and Koepfli et al.[62] (Additional file 6). The phylogenetic relationships of extinct species were assigned following information in published sources (Additional file 3: Table S5). We included branch lengths in million years before present in our composite phylogeny [63–65]. Information on the time of divergence between living taxa was obtained from Nyakatura and Bininda-Emonds [37] and Koepfli et al. [62]. The branch lengths of extinct species were inferred from the stratigraphic range of taxa from different references and public databases (Additional file 3: Table S5).

Phylogenetic tree topology of carnivoran species used in this study. The extinct creodonts (order Creodonta) Patriofelis sp. and Hyaenodon pervagus are used as outgroups to root the tree (see text for details). Tree topology and branch lengths were taken from the literature (Additional file 3: Table S5).

A permutation test was used to assess the presence of a phylogenetic signal in bone shape and size [66, 67] (see [68] for more details).

The effect of size on limb bone shape

Multivariate regression [69] was performed to evaluate the effects of interspecific allometry of shape (Pco) on size (Log-transformed Cs) for each bone. However, species cannot be treated as statistically independent data points because they are related by phylogeny [70]. Thus, independent contrasts analysis [71] was applied to the shape and size of limb bones. Multivariate regression of independent contrasts for shape on independent contrasts for Log-transformed centroid size was performed to investigate the effects of evolutionary allometry. Finally, these regression vectors were applied to the species dataset to obtain the residuals following the method of Klingenberg and Marugán-Lobón [72]. These residuals were used in all multivariate analyses.

A permutation test (10,000 iterations) was used to assess the statistical significance of all the regressions versus the null hypothesis of complete size independence [73].

Phenotypic variability and evolution

Principal Components Analysis was used to investigate phenotypic variation from the covariance matrix of the shape of the bones. In addition, to reconstruct the phylogenetic history of phenotypic space occupation, we created phylomorphospaces for each hind limb bone [38, 64, 67, 68, 74–79].

The influence of locomotor behaviour on limb bone shape

We classified extant carnivoran species within different locomotor groups (Additional file 3: Table S1) following the categories of Samuels et al. [27] to quantify the influence of locomotor behaviour on limb bone shape: (1) cursorial, i.e., species that display rapid locomotion on the ground by galloping; (2) scansorial, i.e., species that are able of climbing but do not forage in trees; (3) arboreal, i.e., species that forage in trees; (4) semifossorial, i.e., species that typically dig; (5) semiaquatic, i.e., species that typically swim; and (6) terrestrial, i.e., species that do not climb, swim, or typically run quickly.

A between-group PCA was performed following the approach of Mitteroecker and Bookstein [80]. We averaged the size-free shapes of all the species within the six locomotor groups. We then computed the PCs from these six averages and plotted the species by applying these eigenvectors to the species. This methodology reveals the morphological axes that better differentiate the group averages. In addition, between-group PCA avoids the problems of Canonical Variate Analysis associated with a small within-group sample size when the dimensionality of the data is high [80]. Subsequently, we created between-group phylomorphospaces for each limb bone shape. We used these phylomorphospaces to investigate whether there is a phylogenetic pattern in the distribution of species even though the PCs were obtained to specifically investigate ecological influences in shape variation.

Availability of supporting data

The data sets supporting the results of this article are available in the Dryad Digital Repository: doi:10.5061/dryad.8h6nf [81].

References

Ewer RF: The Carnivores. 1973, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press

Biewener AA: Animal Locomotion. 2003, Oxford: Oxford University Press

Wilson DE, Mittermeier RA: Carnivores. Handbook of the Mammals of the World. 2009, Barcelona: Lynx Edicions, 1:

Alexander RM: Principles of Animal Locomotion. 2003, Princeton: Princeton University Press

Hildebrand M: Walking and running. Functional Vertebrate Morphology. Edited by: Hildebrand M, Bramble DM, Liem KF, Wake DB. 1985, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 38-57.

Gonyea WJ: Functional implications of felid forelimb morphology. Acta Anat. 1978, 102: 111-121. 10.1159/000145627.

Garland TJ, Janis CM: Does metatarsal/femur ratio predict maximal running speed in cursorial mammals?. J Zool. 1993, 229: 133-151. 10.1111/j.1469-7998.1993.tb02626.x.

MacLeod N, Rose KD: Inferring locomotor behavior in Paleogene mammals via eigenshape analysis. Am J Sci. 1993, 293: 300-355. 10.2475/ajs.293.A.300.

Janis CM, Wilhelm PB: Were there mammalian pursuit predators in the Tertiary? Dances with wolf avatars. J Mammal Evol. 1993, 1: 103-125. 10.1007/BF01041590.

Argot C: Functional-adaptive anatomy of the forelimb in the Didelphidae, and the paleobiology of the Paleocene marsupials Mayulestes ferox and Pucadelphys andinus. J Morphol. 2001, 247: 51-79. 10.1002/1097-4687(200101)247:1<51::AID-JMOR1003>3.0.CO;2-#.

Samuels JX, Van Valkenburgh B: Skeletal indicators of locomotor adaptations in living and extinct rodents. J Morphol. 2008, 269: 1387-1411. 10.1002/jmor.10662.

Halenar LB: Reconstructing the locomotor repertoire of Protopithecus brasiliensis. II. Forelimb morphology. Anat Rec. 2011, 294: 2048-2063. 10.1002/ar.21499.

Ercoli MD, Prevosti FJ, Álvarez A: Form and function within a phylogenetic framework: locomotory habits of extant predators and some Miocene Sparassodonta (Metatheria). Zool J Linn Soc. 2012, 165: 224-251. 10.1111/j.1096-3642.2011.00793.x.

Janis CM, Shoshitaishvili B, Kambic R, Figueirido B: On their knees: distal femur asymmetry in ungulates and its relationship to body size and locomotion. J Vertebr Paleontol. 2012, 32: 433-445. 10.1080/02724634.2012.635737.

Alberch P: Ontogenesis and morphological diversification. Am Zool. 1980, 20: 653-667.

Smith JM, Burian R, Kauffman S, Alberch P, Campbell J, Goodwin B, Lande R, Raup D, Wolpert L: Developmental constraints and evolution: a perspective from the Mountain Lake conference on development and evolution. Q Rev Biol. 1985, 60: 265-287. 10.1086/414425.

Schwenk K, Wagner GP: Constraint. Key words and concepts in evolutionary developmental biology. Edited by: Hall BK, Olson WM. 2003, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 52-61.

Alexander RM: Body support, scaling and allometry. Functional Vertebrate Morphology. Edited by: Hildebrand M, Bramble DM, Liem KF, Wake DB. 1985, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 38-57.

Alexander RM: Models and the scaling of energy costs for locomotion. J Exp Biol. 2005, 208: 1645-1652. 10.1242/jeb.01484.

Biewener AA: Locomotory stresses in the limb bones of two small mammals: the ground squirrel and chipmunk. J Exp Biol. 1983, 103: 135-154.

Biewener AA: Biomechanical consequences of scaling. J Exp Biol. 2005, 208: 1665-1676. 10.1242/jeb.01520.

Doube M, Conroy AW, Christiansen P, Hutchinson JR, Shefelbine S: Three-dimensional geometric analysis of felid limb bone allometry. PLoS One. 2009, 4: e4742-10.1371/journal.pone.0004742.

Fabre AC, Cornette R, Peigné S, Goswami A: Influence of body mass on the shape of forelimb in musteloid carnivorans. Biol J Linn Soc Lond. 2013, 110: 91-103. 10.1111/bij.12103.

Van Valkenburgh B: Skeletal indicators of locomotor behavior in living and extinct carnivores. J Vertebr Paleontol. 1987, 7: 162-182. 10.1080/02724634.1987.10011651.

Schutz H, Guralnick RP: Postcranial element shape and function: Assessing locomotor mode in extant and extinct mustelid carnivorans. Zool J Linn Soc. 2007, 150: 895-914. 10.1111/j.1096-3642.2007.00303.x.

Walmsley A, Elton S, Louys J, Bishop LC, Meloro C: Humeral epiphyseal shape in the felidae: the influence of phylogeny, allometry, and locomotion. J Morphol. 2012, 273: 1424-1438. 10.1002/jmor.20084.

Samuels JX, Meachen JA, Sakay SA: Postcranial morphology and the locomotor habits of living and extinct carnivorans. J Morphol. 2013, 274: 121-146. 10.1002/jmor.20077.

Fabre AC, Cornette R, Slater G, Argot C, Peigné S, Goswami A, Pouydebat E: Getting a grip on the evolution of grasping in musteloid carnivorans: a three-dimensional analysis of forelimb shape. J Evol Biol. 2013, 26: 1521-1535. 10.1111/jeb.12161.

Anyonge W: Locomotor behaviour in Plio-Pleistocene sabre-tooth cats: a biomechanical analysis. J Zool. 1996, 238: 395-413. 10.1111/j.1469-7998.1996.tb05402.x.

Andersson K, Werdelin L: The evolution of cursorial carnivores in the Tertiary: implications of elbow-joint morphology. Proc R Soc Lond B. 2003, 270: 163-165. 10.1098/rsbl.2003.0070.

Andersson K: Elbow-joint morphology as a guide to forearm function and foraging behaviour in mammalian carnivores. J Zool. 2004, 142: 91-104.

Andersson K: Were there pack-hunting canids in the Tertiary, and how can we know?. Paleobiology. 2005, 31: 56-72.

Meachen-Samuels JA, Van Valkenburgh B: Forelimb indicators of prey-size preference in the Felidae. J Morphol. 2009, 270: 729-744. 10.1002/jmor.10712.

Meachen-Samuels JA, Van Valkenburgh B: Radiographs reveal exceptional forelimb strength in the sabertooth cat, Smilodon fatalis. PLoS One. 2010, 5: e11412-10.1371/journal.pone.0011412.

Figueirido B, Janis CM: The predatory behaviour of the thylacine: Tasmanian tiger or marsupial wolf?. Biol Lett. 2011, 7: 937-940. 10.1098/rsbl.2011.0364.

Meachen-Samuels JA: Morphological convergence of the prey-killing arsenal of sabertooth predators. Paleobiology. 2012, 38: 715-728.

Nyakatura K, Bininda-Emonds ORP: Updating the evolutionary history of Carnivora (Mammalia): a new species-level supertree complete with divergence time estimates. BMC Biol. 2012, 10: 12-10.1186/1741-7007-10-12.

Martin-Serra A, Figueirido B, Palmqvist P: A three-dimensional analysis of morphological evolution and locomotor performance of the carnivoran forelimb. PLoS One. 2014, 9: e85574-10.1371/journal.pone.0085574.

Lee DV, Bertram JE, Todhunter RJ: Acceleration and balance in trotting dogs. J Exp Biol. 1999, 202: 3565-3573.

Walter RM, Carrier DR: Ground forces applied by galloping dogs. J Exp Biol. 2007, 210: 208-216. 10.1242/jeb.02645.

Harris MA, Steudel K: Ecological correlates of hind-limb length in the Carnivora. J Zool. 1997, 241: 381-408. 10.1111/j.1469-7998.1997.tb01966.x.

Williams SB, Usherwood JR, Jespers K, Channon AJ, Wilson AM: Exploring the mechanical basis for acceleration: pelvic limb locomotor function during accelerations in racing greyhounds (Canis familiaris). J Exp Biol. 2009, 212: 550-565. 10.1242/jeb.018093.

Iwaniuk AN, Pellis SM, Whishaw IQ: The relationship between forelimb morphology and behaviour in North American carnivores (Carnivora). Can J Zool. 1999, 77: 1064-1074. 10.1139/z99-082.

McMahon TA: Size and shape in biology. Science. 1973, 179: 1201-1204. 10.1126/science.179.4079.1201.

Bertram JEA, Biewener AA: Differential scaling of the long bones in the terrestrial Carnivora and other mammals. J Morphol. 1990, 204: 157-169. 10.1002/jmor.1052040205.

Polly PD: Limbs in mammalian evolution. Fins into Limbs: Evolution, Development and Transformation. Edited by: Hall BK. 2007, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 245-268.

Kardong KV: Vertebrates: comparative anatomy, function, evolution. 2006, Boston: McGraw-Hill

Taylor ME: Locomotor adaptations by carnivores. Carnivore Behaviour, Ecology, and Evolution. Edited by: Gittleman JL. 1989, New York: Cornell University Press, I: 382-409.

Steudel K, Beattie J: Scaling of cursoriality in mammals. J Morphol. 1993, 217: 55-63. 10.1002/jmor.1052170105.

Stein BR, Casinos A: What is a cursorial mammal?. J Zool. 1997, 242: 85-92.

Salesa MJ, Antón M, Turner A, Morales J: Functional anatomy of the forelimb in Promegantereon ogygia (Felidae, Machairodontinae, Smilodontini) from the Late Miocene of Spain and the origins of the sabre-toothed felid model. J Anat. 2010, 216: 381-396. 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2009.01178.x.

Martin LD, Babiarz JP, Naples VL, Hearst J: Three ways to be a saber-toothed cat. Naturwissenschaften. 2000, 87: 41-44. 10.1007/s001140050007.

Van Valkenburgh B: Locomotor diversity within past and present guilds of large predatory mammals. Paleobiology. 1985, 11: 406-428.

Van Valkenburgh B: Deja vu: the evolution of feeding morphologies in the Carnivora. Integr Comp Biol. 2007, 47: 147-163. 10.1093/icb/icm016.

Gunnell GF: Creodonta. Evolution of Tertiary mammals of North America: Volume 1, terrestrial carnivores, ungulates, and ungulate like mammals. Edited by: Janis CM, Scott KM, Jacobs LL. 1998, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 91-109.

Barone R: Anatomie Compare des Mammifères Domestiques, Ostéologie, Volume 1. 1986, Paris: Vigot

Homberger DG, Walker WF: Vertebrate dissection. 2004, Belmont, CA: Brooks Cole, 9

Wiley DF, Amenta N, Alcantara DA, Ghosh D, Kil YJ, Delson E, Harcourt-Smith W, Rohlf FJ, St John K, Hamann B: Evolutionary Morphing. Proceedings of IEEE Visualization 2005 (VIS’05); Minneapolis. 2005, 431-438.

Dryden IL, Mardia K: Statistical Analysis of Shape. 1998, Chichester, UK: Wiley

Klingenberg CP: MorphoJ. 2011, Manchester: Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Manchester, http://www.flywings.org.uk/MorphoJ_page.htm,

Maddison WP, Maddison DR: Mesquite: a modular system for evolutionary analysis. Version 2.75. 2011, http://mesquiteproject.org,

Koepfli KP, Gompper ME, Eizirik E, Ho CC, Linden L, Maldonado JE, Wayne RK: Phylogeny of the Procyonidae (Mammalia: Carnivora): molecules, morphology and the great American interchange. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2007, 43: 1076-1095. 10.1016/j.ympev.2006.10.003.

Polly PD: Paleontology and the comparative method: ancestral node reconstructions versus observed node values. Am Nat. 2001, 157: 596-609. 10.1086/320622.

Polly PD: Adaptive Zones and the Pinniped Ankle: a 3D Quantitative Analysis of Carnivoran Tarsal Evolution. Mammalian Evolutionary Morphology: A Tribute to Frederick S. Szalay. Edited by: Sargis E, Dagosto M. 2008, Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer, 65-194.

Finarelli JA, Flynn JJ: Ancestral state reconstruction of body size in the Caniformia (Carnivora, Mammalia): the effects of incorporating data from the fossil record. Syst Biol. 2006, 55: 301-313. 10.1080/10635150500541698.

Laurin M: The evolution of body size, Cope’s rule and the origin of amniotes. Syst Biol. 2004, 53: 594-622. 10.1080/10635150490445706.

Gidaszewski NA, Baylac M, Klingenberg CP: Evolution of sexual dimorphism of wing shape in the Drosophila melanogaster subgroup. BMC Evol Biol. 2009, 9: 110-10.1186/1471-2148-9-110.

Klingenberg CP, Gidaszewski NA: Testing and quantifying phylogenetic signals and homoplasy in morphometric data. Syst Biol. 2010, 59: 245-261. 10.1093/sysbio/syp106.

Monteiro LR: Multivariate regression models and geometric morphometrics: the search for causal factors in the analysis of shape. Syst Biol. 1999, 48: 192-199. 10.1080/106351599260526.

Harvey PH, Pagel MD: The comparative method in evolutionary biology. 1991, Oxford, UK: Oxford Univ Press

Felsenstein JJ: Phylogenies and the comparative method. Am Nat. 1985, 125: 1-15. 10.1086/284325.

Klingenberg CP, Marugán-Lobón J: Evolutionary covariation in geometric morphometric data: analyzing integration, modularity, and allometry in a phylogenetic context. Syst Biol. 2013, 62: 591-610. 10.1093/sysbio/syt025.

Drake AG, Klingenberg CP: The pace of morphological change: historical transformation of skull shape in St Bernard dogs. Proc Biol Sci. 2008, 275: 71-76. 10.1098/rspb.2007.1169.

Klingenberg CP, Ekau W: A combined morphometric and phylogenetic analysis of an ecomorphological trend: pelagization in Antarctic fishes (Perciformes: Nototheniidae). Biol J Linn Soc Lond. 1996, 59: 143-177. 10.1111/j.1095-8312.1996.tb01459.x.

Rohlf FJ: Geometric morphometrics and phylogeny. Morphology, shape, and phylogeny. Edited by: MacLeod N, Forey PL. 2002, London: Taylor and Francis, 175-193.

Figueirido B, Serrano-Alarcón FJ, Slater GJ, Palmqvist P: Shape at the cross-roads: homoplasy and history in the evolution of the carnivoran skull towards herbivory. J Evol Biol. 2010, 23: 2579-2594. 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2010.02117.x.

Klingenberg CP, Dutke S, Whelan S, Kim M: Developmental plasticity, morphological variation and evolvability: a multilevel analysis of morphometric integration in the shape of compound leaves. J Evol Biol. 2012, 25: 115-129. 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2011.02410.x.

Sakamoto M, Ruta M: Convergence and divergence in the evolution of cat skulls: temporal and spatial patterns of morphological diversity. PLoS One. 2012, 7: e39752-10.1371/journal.pone.0039752.

Figueirido B, Tseng ZJ, Martín-Serra A: Skull shape evolution in durophagous carnivorans. Evolution. 2013, 67: 1975-1993. 10.1111/evo.12059.

Mitteroecker P, Bookstein F: Linear discrimination, ordination, and the visualization of selection gradients in modern morphometrics. Evol Biol. 2011, 38: 100-114. 10.1007/s11692-011-9109-8.

Martín-Serra A, Figueirido B, Palmqvist P: Data from: a three-dimensional analysis of the morphological evolution and locomotor behaviour of the carnivoran hind limb. BMC Evol Biol. 2014, doi: 10.5061/dryad.8h6nf

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to F. Serrano, C. M. Janis and J. A. Pérez-Claros, C. P. Klingenberg and two anonymous reviewers for their helpful discussions and comments, which helped us to improve the quality of this paper. We thank J. Galkin and E. Westwig (AMNH, New York), R. Portela and A. Currant (NHM, London), J. Morales and M. J. Salesa (MNCN, Madrid), M. Belinchón (MCNV, Valencia), L. Costeur (NMB, Basel), E. Cioppi (MSN, Firenze) and K. L. Hansen (SNM, Copenhagen) for kindly providing us with access to the specimens under their care and to S. Almécija for providing us with the bone scanning surfaces. This study was supported by a PhD Research Fellowship (FPU) to AM-S from the “Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia” and the CGL2012-37866 grant to BF from the “Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

AMS collected the data. AMS and BF conducted the analyses. AMS, BF, and PP wrote the manuscript. PP provided advice on the analyses. AMS, BF, and PP conceived and designed the study. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12862_2013_2611_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Additional file 1: Interactive three-dimensional models of shape variation in the carnivoran hind limb. Size-related shape changes for pelvis (A), femur (B) and tibia (C). Left indicates negative regression scores and right positive scores. (PDF 1 MB)

12862_2013_2611_MOESM2_ESM.pdf

Additional file 2: Three-dimensional models showing the shape changes obtained from the PCAs. Pelvis (A), femur (B) and tibia (C). PC I top, PC II bottom; left for negative scores, right for positive scores. (PDF 2 MB)

12862_2013_2611_MOESM4_ESM.pdf

Additional file 4: Three-dimensional models showing the shape changes obtained from the between-group PCAs. Pelvis (A), femur (B) and tibia (C). PC I top, PC II bottom; left for negative scores, right for positive scores. (PDF 2 MB)

12862_2013_2611_MOESM5_ESM.xls

Additional file 5: Table in Excel format with morphometric data averaged per species for each hind limb bone analysed. Centroid size, log-transformed centroid size and Procrustes coordinates are shown for pelvis (1st and 2nd sheets), femur (3rd and 4th sheets) and tibia (5th and 6th sheets). 1st, 3rd and 5th sheets show values for all the species; 2nd, 4th and 6th sheets include only extant species. (XLS 384 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Martín-Serra, A., Figueirido, B. & Palmqvist, P. A three-dimensional analysis of the morphological evolution and locomotor behaviour of the carnivoran hind limb. BMC Evol Biol 14, 129 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-14-129

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-14-129