Abstract

We study one-loop effects induced by an anomalous Higgs trilinear coupling on total and differential rates for the \(H\rightarrow 4\ell \) decay and some of the main single-Higgs production channels at the LHC, namely, VBF, VH, \(t{\bar{t}}H\) and tHj. Our results are based on a public code that calculates these effects by simply reweighting samples of Standard-Model-like events for a given production channel. For VH and \(t{\bar{t}}H\) production, where differential effects are particularly relevant, we include Standard Model electroweak corrections, which have similar sizes but different kinematic dependences. Finally, we study the sensitivity of future LHC runs to determine the trilinear coupling via inclusive and differential measurements, considering also the case where the Higgs couplings to vector bosons and the top quark is affected by new physics. We find that the constraints on the couplings and the relevance of differential distributions critically depend on the expected experimental and theoretical uncertainties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Since its discovery in 2012 [1, 2], evidence has been steadily accumulating that the properties of the scalar particle at 125 GeV correspond to those of the Higgs boson predicted by the Standard Model (SM) of elementary particles and interactions. ATLAS and CMS experiments have analyzed data from several inverse femtobarns of integrated luminosity at different energies, providing already rather precise measurements of the Higgs couplings to the vector bosons and to the fermions of the third generation [3,4,5,6,7]. Prospects of the next LHC runs for further improving the precision on the value of these couplings and for measuring also the couplings to the second-generation fermions are very good. On the contrary, the situation and prospects for determining the properties of the scalar potential, i.e., of the Higgs self-couplings at the LHC are less clear and therefore the subject of an intense theoretical and experimental activity.

At low energy, the potential for a scalar particle of mass \(m_H\) can be parametrized as a polynomial,

where \(v=(\sqrt{2}G_F)^{-1/2} \sim 246~\mathrm{GeV}\) is the vacuum expectation value after electroweak-symmetry-breaking (EWSB). In the SM, renormalizability and gauge invariance dictate that the Higgs potential depends only on two parameters, \(\mu \) and \(\lambda \),

where \(\Phi \) is the Higgs doublet. After EWSB the potential in Eq. (2) gives rise to the mass of the physical Higgs boson \(m_H\), which, together with the vacuum expectation value v, are related to \(\mu \) and \(\lambda \) via \(\mu ^2=m_H^2/2\) and \(\lambda =m_H^2/(2v^2)\). As a result, by fixing \(\mu \) and \(\lambda \), in the SM the Higgs self-couplings are completely determined, leading in Eq. (1) to \(\lambda _i=\lambda _i^{\mathrm{SM}}\) with \(\lambda _3^{\mathrm{SM}} = \lambda _4^{\mathrm{SM}} = \lambda \) and \(\lambda _i^{\mathrm{SM}} = 0\) for \(i\ge 5\), at LO. Thus, with \(m_H=125~\mathrm{GeV}\),

On the other hand, new physics could modify the Higgs potential at low energy, by altering the value of \(\lambda _3\) (or in general \(\lambda _i\) for the i-point Higgs self-couplings) without affecting the value of \(m_H\) and v. This can be realized either directly (e.g. by extending the scalar sector) or indirectly (due to the exchange of new virtual states). In addition, modifications in the self-interactions would be induced if the Higgs boson is a composite state.

Since double Higgs production directly depends on the Higgs trilinear coupling at LO, it is the standard process for studying \(\lambda _3\) at the LHC. However, the cross section of its main production channel, the gluon fusion, is only about 35 fb at 13 TeV [8,9,10], so it is much smaller than single Higgs production cross section, which is about 50 pb [11]. Several phenomenological studies have been performed on the determination of \(\lambda _3\) via the relevant experimental signatures emerging from this process: \(b\bar{b} \gamma \gamma \) [12,13,14,15,16,17], \(b\bar{b}\tau \tau \) [13, 18], \(b\bar{b}W^+W^-\) [19] and \(b\bar{b}b\bar{b}\) [20,21,22]. Also \(t{{\bar{t}}}HH\) [23, 24] and VHH [25] production processes have beeen considered. Nevertheless, given the complexity of a realistic experimental set-up, the final precision that could be achieved on the determination of \(\lambda _3\) is still unclear. On the contrary, it is established that at the LHC perspectives of inferring information on \(\lambda _4\) from the triple Higgs production are quite bleak [26, 27], due to the smallness of the corresponding cross section [8, 28], together with a rather weak dependence on this parameter. Even at a future 100 TeV proton–proton collider a considerable amount of integrated luminosity will be necessary in order to obtain rather loose bounds [29,30,31].

At the moment the strongest experimental bounds on non-resonant double-Higgs production have been obtained in the CMS analysis of the \(b\bar{b}\gamma \gamma \) signature [32], where cross sections larger than about 19 times the predicted SM value have been excluded. However, exclusion limits on \(\lambda _3\) are found to be strongly dependent on the value of the top–Higgs coupling and they are of the order \( \lambda _3<-\ 9 ~\lambda _3^{\mathrm{SM}}\) and \(\lambda _3> 15 ~\lambda _3^{\mathrm{SM}}\) for the SM-like case. These new limits, together with the slightly weaker ones from the ATLAS \(b\bar{b}b\bar{b}\) [33] and CMS \(b\bar{b}\tau \tau \) [34] analyses at 13 TeV, improve the results from 8 TeV data (\(\lambda _3< - \ 17.5 ~\lambda _3^{\mathrm{SM}}\) and \(\lambda _3> 22.5 ~ \lambda _3^{\mathrm{SM}}\) [35]), however, also with a high integrated luminosity (HL) of 3000 fb\(^{-1}\), a further improvement may not be so tremendous. The most optimistic experimental studies for HL-LHC suggest that it could be possible to exclude values in the range \(\lambda _3<- \ 1.3 ~\lambda _3^{\mathrm{SM}}\) and \(\lambda _3>8.7 ~ \lambda _3^{\mathrm{SM}}\) via the \(b\bar{b} \gamma \gamma \) signatures [36]. Additional and complementary strategies for the determination of \(\lambda _3\) are thus desirable at the moment.

In Ref. [37] an indirect method of measuring \(\lambda _3\) via EW radiative corrections in \(e^+e^- \rightarrow ZH\) process was proposed. Recently, the same idea has also been extended to the LHC, by (globally) studying \(\lambda _3\)-dependent EW corrections in single Higgs production and decay processes [38,39,40,41]. Moreover, limits on \(\lambda _3\) can also be derived by two-loop effects in EW precision observables [42, 43] such as the measurements of \(m_W\) and of the S, T oblique parameters. These studies have confirmed that indirect bounds on \(\lambda _3\) can be competitive with the direct ones inferred from the di-Higgs production channel. For example, a simple one-parameter fit to the signal-strengths’ measurements at 8 TeV [7] gives \(- \ 9.4~\lambda _3^{\mathrm{SM}}<~\lambda _3<17.0~\lambda _3^{\mathrm{SM}}\) [39], comparable to the current best constraints from the \(b\bar{b}\gamma \gamma \) CMS measurement mentioned above. In both analyses no other deviations for the Higgs couplings are considered. The usefulness of a joint analysis of \(\lambda _3\) indirect effects on single-Higgs production and direct effects on di-Higgs production has been discussed and quantified in Ref. [41]. As already suggested in Refs. [39, 40], the role of differential distributions and their non-flat dependence on \(\lambda _3\) has been proved to be crucial in Ref. [41], especially when not only anomalous \(\lambda _3\) effects but also modifications of the couplings to the other particles are considered, as expected in a general effective-field-theory (EFT) approach.

The purpose of this work is threefold. First, we present an automated public code for generating events including \(\lambda _3\) effects at one loop, thus allowing the study of differential effects in VBF, VH and \(t {\bar{t}} H\) productionFootnote 1 and all the relevant Higgs decays. The code is based on two independent and procedurally different implementations in the MadGraph5_aMC@NLO framework [44].Footnote 2 Second, with the help of this code, we extend at the differential level the results of Ref. [39], where all the relevant single Higgs production (\(gg\mathrm{F}\), \(\mathrm{VBF}\), VH, \(t{\bar{t}}H\)) and decay channels (\(\gamma \gamma \), \(VV^*\), ff, gg) have been analyzed and included in a global fit only at the inclusive level. Indeed, in Ref. [39] the usefulness of differential distributions has already been explored but only for the case of VH and \(t {\bar{t}} H\) production, providing the results on which the analysis in Ref. [41] rely. Differential information for VBF and VH production has been presented also in Ref. [40]. Here we scrutinize all the relevant distributions that are potentially affected by anomalous \(\lambda _3\) effects, presenting for the first time detailed results at the differential level for \(t {\bar{t}} H\) production, for the \(H\rightarrow 4\ell \) decay and also for the tHj process, for which also inclusive results are new. Moreover, for the case of VH and \(t {\bar{t}} H\) production, where loop-induced \(\lambda _3\) effects are not flat, we repeat the calculation of NLO EW corrections [45,46,47,48,49,50] in the SM, which are also not flat, in order to check the robustness of our strategy. As expected, we find that NLO EW corrections are essential for a precise determination of anomalous \(\lambda _3\) effects, but also that they do not jeopardize the sensitivity of indirect \(\lambda _3\) determination. We use for the calculation the EW extension of the automated MadGraph5_aMC@NLO framework that has already been used and validated in Refs. [48, 49, 51,52,53,54].Footnote 3

Finally we perform a fit for \(\lambda _3\) based on the future projections of ATLAS-HL for single-Higgs production and decay at 14 TeV [55, 56]. We consider the effects induced on the fit by additional degrees of freedom, namely anomalous Higgs couplings with the vector bosons and/or the top quark. We investigate the impact on the fit of three different factors: the differential information, the experimental and theoretical uncertainties, and the inclusion of the two aforementioned additional degrees of freedom. We find that in a global fit, including all the possible production and decay channels, two additional degrees of freedom such as those considered here do not preclude the possibility of setting sensible \(\lambda _3\) bounds, especially, they have a tiny impact on the upper bound for positive \(\lambda _3\) values. On the contrary the role of differential information may be relevant, depending on the assumptions on experimental and theoretical uncertainties.

The structure of the paper is the following. In Sect. 2 we briefly repeat and comment on the main formulas that are relevant in the study of one-loop induced \(\lambda _3\) effects. Differential results for the various processes that have been mentioned before are given in Sect. 3. In Sect. 4 we present the extension of the analysis of \(\lambda _3\) effects including NLO EW corrections and we study the impact on differential distributions and inclusive rates. In Sect. 5 we introduce the framework for the fit and discuss the results obtained. Details as regards the statistical treatment of uncertainties in the fit are collected in Appendix A.

2 Technical set-up

2.1 Self-couplings effects in single Higgs production and decays at one loop

Higgs self-couplings can be studied in a model-dependent approach, e.g., choosing a particular UV-complete scenario, or in a model-independent approach, as done in this work. However, there are different ways in which the modifications of trilinear and quartic couplings can be parametrized and they rely on different theoretical assumptions. If new physics is at scales sufficiently higher than the energies where measurements are performed, the SMEFT offers a consistent and model-independent way of organizing generic deformations to the Higgs interactions. Moreover, radiative corrections can be consistently performed within this framework. However, it has been shown [39] that in the case of the trilinear coupling and at the order we are considering, one-loop corrections for single Higgs processes, adding higher-dimensional operators that only affect the Higgs self-couplings (the \((\Phi \Phi ^\dag )^n\) operators with \(n>2\)) or directly introducing an anomalous coupling,

are two fully equivalent approaches for deforming the SM Higgs potential. In other words, regarding the Higgs self-couplings, differences between an EFT and an anomalous coupling parametrization will arise only for final states featuring more Higgs bosons and/or at higher loop level, i.e., with the appearance of higher-point interactions (starting from quadrilinear).

It is essential to note that the single Higgs production and the decay channels are not sensitive to \(\lambda _4\) at one loop. For this reason, although results are written in terms of \(\lambda _3\), they can easily be translated in terms of the Wilson coefficient in front of the dimension-6 operator \((\Phi \Phi ^\dag )^3\), or those for higher-dimension \((\Phi \Phi ^\dag )^n\) operators. In the following we briefly repeat and comment the main formulas that have been introduced and discussed at length in Ref. [39]; very minor modifications are present in the notation and in the definition of the corresponding quantities.

The \(\lambda _3\)-dependent part of the NLO EW corrections to single Higgs processes are gauge invariant and finite. These contributions can be organized in two categories: a universal part proportional to \((\lambda _3)^2\), which arises from the wave-function renormalization of external Higgs boson and thus does not depend on the kinematics, and a process-dependent part linear in \(\lambda _3\), which is also sensitive to the kinematics. In the presence of modified trilinear coupling, the master formula for the \(\lambda _3\)-dependence of a generic observable \(\Sigma \) (total/differential cross section or decay width) can be written as

where \(C_1\) is the process- and kinematic-dependent component and \(\Sigma _{\mathrm{LO}}\) stands for the LO prediction including any factorizable higher-order correction. In particular, we assume that QCD corrections do in general factorize, which, for the VH and VBF case, has been shown to be a correct approach up to NNLO in Ref. [40].Footnote 4 Representative diagrams contributing to the \(C_1\) for the different processes are depicted in Fig. 1.

In Eq. (5), at variance with the case of \(\Sigma _{\lambda _3}^{\mathrm{NLO}}\) in Ref. [39], the universal component \(Z_H^{\mathrm{BSM}}\) corresponds to the wave-function renormalization where we have resummed only the new-physics contributions at one loop,

The SM component is directly included at fixed NLO via the \(\delta Z_H\) term appearing in Eq. (5). Numerically, the difference between Eq. (5) and \(\Sigma _{\lambda _3}^{\mathrm{NLO}}\) in Ref. [39] is at sub-permill level and thus negligible. On the other hand, in the limit \(\kappa _3\rightarrow 1\), \(Z_H^{\mathrm{BSM}}\rightarrow 1\) and thus \(\Sigma _{\lambda _3}^{\mathrm{BSM}}\) goes to the SM case at fixed NLO

This is particularly convenient for the discussion in Sect. 4, where we will analyze NLO EW corrections in the SM in conjunction with \(\lambda _3\)-induced effects. In conclusion, the relative corrections due to the trilinear coupling can be expressed as

which manifestly goes to zero in the \(\kappa _3\rightarrow 1\) limit.

Numerical values of \(C_1\) at the inclusive level for the processes considered in this work are reported in Table 1. The calculation of \(C_1\) for single-top–Higgs production, which appears for the first time here, is non-trivial and discussed in Sect. 3.4. The range of validity of Eq. (9) has been identified in Ref. [39] as \(|\kappa _3| < 20\), given the values of \( \delta Z_H\) and \(C_1\) in Table 1. As we will see, at the differential level this limit may be too loose since \(C_1\) can receive large enhancements (see Sect. 3.3). On the other hand, we believe that the constraint \(|\kappa _3| \lesssim 6\) identified in Ref. [57] is appropriate for inclusive double Higgs production, but it is too strong for the case of single-Higgs production. Indeed the violation of perturbativity for the HHH vertex is kinematic dependent and the condition \(|\kappa _3| \lesssim 6\) arises from the configuration with two H bosons on-shell and the third one with virtuality slightly larger than \(2m_{H}\). This is the kinematic configuration present above the threshold in double Higgs production, where the bulk of its cross section comes from, but is never present in single Higgs production, since only one Higgs boson can be on-shell in the HHH vertex appearing at one loop.

2.2 Automated codes for the event-by-event calculation of \(C_1\)

While \(\delta Z_H\) is a universal quantity, \(C_1\) is process and kinematics dependent. We have employed two independent methods for the computation of \(C_1\) for differential cross sections and decay rates. They correspond to the two different codes publicly available, which agree within their numerical accuracy. In the first we parametrize the finite one-loop corrections due to the trilinear Higgs self-coupling as form factors that are functions of the external momenta. One-loop integrals are computed using the LoopTools package [58] and the form factors are implemented as effective new vertices in a dedicated UFO model file [59], which is then used in MadGraph5_aMC@NLO [44]. As a result, parton-level events can be generated including \({{\mathscr {O}}}(\lambda _3)\) effects and any interesting observable analyzed. Our current implementation of form factors allows the computation of differential \(C_1\) for VBF, VH and \(H \rightarrow 4l\) processes. At the order of accuracy of our calculation, ggF production and all the other \(1 \rightarrow 2\) decays do not have a kinematic dependence for \(C_1\); results at the inclusive level are sufficient for any kinematic configuration and thus taken from Ref. [39].

On the other hand, the implementation of form factors for \(t {\bar{t}} H\) and tHj processes would be quite cumbersome as there are many one-loop integrals that contribute. A different strategy, based on reweighting, has therefore been devised. With this second method, one starts by generating a sample of (unweighted) parton-level events at leading order. These events are then used as input for a code that computes the momentum-dependent weight

where, following the notation of Ref. [39], \({{{\mathscr {M}}}}^{0 }\) refers to the tree-level amplitude and \({{{\mathscr {M}}}}^{1}_{\lambda ^{\mathrm{SM}}_3}\) to the SM virtual corrections depending on \(\lambda _3\). Then LO events are reweighted by multiplying the weight of each event i by the corresponding \(w_i\). In this way, also with this method it is possible to calculate \(C_1\) for any differential distribution.

The required one-loop matrix elements are computed using the capabilities of MadGraph5_aMC@NLO for evaluating loop diagrams [48, 53, 60, 61]. For each process, we use diagram filters in order to select the relevant one-loop matrix elements featuring the Higgs self-coupling. We find this method much faster and efficient than the one based on form factors also for VH and VBF processes, thus we actually employ it for deriving all the results presented in this work and we suggest the usage of this version of the code. Note, however, that the other method offers at least in principle the possibility of explicitly including NLO QCD corrections on top of \(\lambda _3\)-induced effects for VBF and VH production.

3 Results for differential distributions

Results are presented in this section and have been obtained with the following input parameters:

which are taken from Ref. [62]. We use as PDF set the PDF4LHC2015 distributions with the factorization scale at \( \mu _F = \frac{1}{2} \sum _i m (i)\), where m(i) are the masses of the particles i in the final state.Footnote 5 In the following subsections we provide differential results for various relevant observables in VBF, VH, \(t {\bar{t}} H\) and tHj production channels and in the \(H \rightarrow 4l\) decay channel. Each plot has the layout that is described in the following. The upper panel displays the LO distribution (red) and \({{\mathscr {O}}}(\lambda _3)\) corrections alone (blue), both normalized by their value for the total cross section. In other words, we compare the shape of LO distributions with the shape of the contributions induced by \(C_1\) in Eq. (5), which is thus independent on the value of \(\kappa _3\). The lower panel display \(C_1\) both at differential level (green) and for the total cross section/decay (blue). The latter values are also summarized in Table 1 and will be used in Sect. 5 for the representative fit results.

3.1 VBF

Vector boson fusion is generated by requiring EW production of Higgs plus two jets, which includes also VH configurations with the vector boson V decaying into two jets. We effectively eliminate VH contributions by applying the following kinematic cuts [62] on the two final-state jets:

In Fig. 2, we present \(C_1\) for representative distributions, namely, \(p_T(H)\), \(p_T(j_1)\), m(jj) and m(Hjj). In fact, we have checked that similar effects characterize other observables, which, however, we do not show. As already noticed in Refs. [39, 40] the value of \(C_1\) is not particularly large and rather flat for all the distributions shown here; \(C_1=0.63 \%\) for the total cross section and never exceeds \(0.70\%\) at the differential level. At variance with the case of VH and \(t {\bar{t}} H\) considered in the following, loop corrections featuring trilinear Higgs self-couplings involve Higgs propagators connecting the final-state Higgs and internal V propagators. Thus, no Sommerfeld enhancement is present at threshold. In this respect, the interest of VBF for what concerns the indirect determination of \(\lambda _3\) is mostly limited to the shift in the total rate, which, even though modest, is anyway relevant. Indeed, VBF is the channel with the second largest cross section and the smallest of the theoretical uncertainties [62], as can also be found in Table 4 in Appendix A.

3.2 \(\mathbf{VH}\)

In Figs. 3 and 4 we show the differential \(C_1\) for ZH and \(WH(W=W^+ , W^-)\), respectively. As discussed in Refs. [39, 40] the main enhancements are present at threshold, where the interaction of the final-state vector and Higgs bosons via a Higgs propagator leads to a Sommerfeld enhancement due to the non-relativistic regime. Indeed the shape of the \({{\mathscr {O}}}(\lambda _3)\) corrections is quite different from the LO case for \(p_T(H)\) and m(VH) distributions; the former are softer than the latter. For this reason, \(C_1\) grows at threshold, where, however, the cross section is rather small. In particular, while \(C_1\) in ZH (WH) is 1.19 (1.03)% at the inclusive level, it grows up to, e.g., 2.3(1.8)% for m(ZH) at threshold, with the binning used in Figs. 3 and 4. Thus, in order to detect anomalous \(\lambda _3\) effects, dedicated measurements close to threshold but with enough events, such as the region \(p_T(H)<75\) GeV, would be desirable. For VH we also show \(C_1\) for the rapidity y(H) and the difference of the pseudo-rapidity of the V and H bosons \(\Delta \eta (V,H)\). The latter is particularly interesting because \(C_1\) is enhanced w.r.t. the inclusive case in the region corresponding to the largest cross section.

We also looked at possible effects due to the Z polarization or, in other words, measurable via the angular distributions of Z (and H) decay products. We did not see any enhancement or shape dependence for these distributions. Furthermore, one should bear in mind that also the loop-induced \(gg\rightarrow HZ\) process gives a non-negligible amount of the NNLO cross section, order \(\sim 1/6\) at 13 TeV. This process also has a dependence on \(\lambda _3\), but only at two-loop level, and should exhibit a shape dependence. However, this calculation is not technically feasible yet.

3.3 \(\mathbf{t}{{\bar{\mathbf{t}}}}{} \mathbf{H} \)

Together with gluon-fusion production, the \(t {\bar{t}} H\) channel plays a major role in providing information of the top-quark couplings to the Higgs. Its importance can be gauged by simply considering its weight in a global \(\kappa \)-framework fit [63] or in the SMEFT framework [62]. The same importance should be ascribed to this process also from the point of view of the sensitivity to \(\lambda _3\): \(C_1\) for \(t {\bar{t}} H\) is the largest among all production channels and with the most significant kinematic dependence [39]. In Fig. 5, we show the most important kinematic distributions in this channel. \(C_1\) for total cross section is \(3.52\%\) and can increase up to \(\sim 5\%\) in \(p_T\) distributions. Similarly, with the binning chosen in Fig. 5, \(C_1\) for the invariant mass distributions can be as large as 10% close to threshold, even though, once again, in the same region the cross section is suppressed by phase space. The origin of the large phase-space dependence of \(C_1\) is again due to Sommerfeld enhancements in the threshold regions that are induced by interactions among the top (anti)quark and the Higgs boson.

3.4 \(\mathbf{tHj}\)

Although it is characterized by a rather small cross section at the LHC, single associate production of a Higgs with a single top is a particularly rich and interesting process, especially in searching for observables sensitive to relative phases among the Higgs couplings to fermions and bosons [64,65,66,67]. Naively, one would expect this process to have a sensitivity to the trilinear one between that of VBF and \(t {\bar{t}} H\); the tHj process features a top quark in the final state as well as W boson(s) in the propagators. The contribution of one-loop diagrams featuring the Higgs self-coupling to this process has not been considered in Ref. [39] for two major reasons. The first one was of phenomenological nature: in the SM this process is barely observable at the Run II of the LHC. The second one is of a technical nature: the calculation needs a careful check of EW gauge invariance and UV finiteness, since a few subtleties, which are not present for the other processes discussed in this work, arise. We describe them in the following.

Similar to the case of the \(H\rightarrow \gamma \gamma \) decay [38, 39], Goldstone bosons appear in the Feynman diagrams contributing to the LO. Thus, HGG and HHGG interactions are present in one-loop EW corrections. While the former is not modified by \((\Phi ^\dag \Phi )^{n}\) effective operators, the latter is indeed modified [38, 39]. The calculation can be consistently performed in two different ways: either directly eliminating Goldstone bosons by employing the unitary gauge, as also done for other quantities in Refs. [39, 42], or keeping track of HHGG effects in the intermediate calculation steps, as we explain in the following and as we actually will do in our calculation.

In a generic gauge, the on-shell renormalization of the EW sector [68] involves the counterterm for the Goldstone self-energy, which depends on the Higgs tadpole counter term \(\delta t\), which in turn depends on the trilinear coupling \(\lambda _3\). Therefore, if we only modify the value of \(\lambda _3\), the Goldstone self-energy counterterm receives a UV-divergent contribution proportional to (\(\kappa _3-1\)), which is not cancelled by any divergence from loop diagrams. Instead, if we consistently take into account the modification of the HHGG vertex, loop diagrams featuring a seagull in the G propagator are also present; they exactly cancel the UV-divergent contribution proportional to \((\kappa _3-1)\) in the Goldstone self-energy counter term, leading to the same result one would obtain in the unitary gauge. Having understood this point, the calculation is straightforward and can be performed automatically in the Feynman gauge.

In our results we include both tHj and \({{\bar{t}}}Hj\) channels and we do not apply cuts on the jet, since the result is infrared finite. We find the \(C_1\) for the total cross section is about 0.91%. In Fig. 6, we show \(C_1\) for kinematic distributions such as \(p_T(H)\), \(p_T(t)\), m(tH) and m(tHj). We note that unlike the other variables \(p_T(t)\) does not decrease monotonically as we move from low to high \(p_T\) values. Near threshold m(tH) displays a quite impressive difference in shape.

3.5 \(\mathbf{H \rightarrow 4\ell }\)

The Higgs decay into four fermions is the only Higgs decay channel with non-trivial final-state kinematics. Moreover, it is the only one where a priori also \(C_1\) can have a shape dependence. Indeed, all the other decays correspond to a \(1\rightarrow 2\) process, and since the H boson is a scalar, there is not a preferred direction in its reference frame. In the previous study [39] the \(C_1\) for \(H \rightarrow ZZ^*\) decay was calculated to be 0.83\(\%\). Although the full off-shell configuration was taken into account, possible angles between the decay products were not analyzed. Using the form-factor code mentioned above we calculate \(C_1\) for \(H \rightarrow e^+e^-\mu ^+\mu ^-\) channel. We analyzed \(C_1\) for many observables involving the four leptons, but we found that it has in general almost no kinematic dependence. As an example, in Fig. 7, we display \(C_1\) for leading and subleading lepton pair invariant masses. Since the Higgs boson interactions with the final-state fermions are negligible, this result can be extended to all the other decays into four leptons and in general into four fermions.

4 Anomalous trilinear effects and the NLO electroweak corrections

The set of one-loop corrections to single Higgs production and decays involving the trilinear Higgs self-coupling is gauge invariant and finite. However, in the SM, performing a perturbative expansion in power of \(\alpha _s\) and \(\alpha \), other contributions are present at the same order of accuracy. In other words, \(\lambda _3\)-induced effects at one-loop level should be considered as a gauge-invariant and finite subset of the complete NLO EW corrections, which also include effects form virtual W, Z and photons as well as real emission contributions.Footnote 6

As shown in the previous section, the possibility of measuring anomalous \(\lambda _3\) effects via precise predictions in single Higgs production relies both on the precision of experimental measurements and SM theory predictions. In particular, regarding the theoretical accuracy, while it is reasonable to assume that QCD corrections in general factorize \(\lambda _3\) effects, as explained in Sect. 2, this is in general not true for NLO EW corrections. The purpose of this section is to provide a consistent extension of the master formula in Eq. (5) that includes also NLO EW corrections and to investigate their impact in the determination of anomalous \(\lambda _3\) effects. All the calculations of the NLO EW corrections in the SM, with the exception of ggF taken from [62], are performed in a completely automated approach via an extension of the MadGraph5_aMC@NLO framework that has already been used and validated in Refs. [48, 49, 51,52,53,54]. Concerning the renormalization, we use the \(G_\mu \)-scheme, consistently with the input parameters listed in Sect. 3.

At the differential level we limit ourselves to the study of the VH and \(t {\bar{t}} H\) processes, where the \(C_1\) dependence on the kinematics is large. We have also computed the differential EW corrections to the tHj production channel, but we do not report plots here, as its phenomenological relevance will be marginal at 13 TeV LHC for our purposes. The differential case is of particular interest since EW corrections in the SM, due to the Sudakov logarithms, are large in the boosted regime, i.e., exactly in the opposite phase-space region where \(\lambda _3\)-induced effects are sizable, the production threshold, as already discussed before.

The master formula in Eq. (5) can be improved including NLO EW correction in the following way:

where \(\delta _{\mathrm{EW}}\big |_{{\lambda }_3=0}\) represents the part of the NLO EW K-factor in the SM

that does not depend on \(\lambda _3\), namely,Footnote 7

In Eq. (14), \( \Sigma _{\mathrm{NLO}}^{\mathrm{SM}}\) stands for the observable \( \Sigma \) at LO + NLO EW accuracy. Thus, in the limit \(\lambda _3\rightarrow 1\), \(\Sigma _{\mathrm{NLO}}^{\mathrm{BSM}} \rightarrow \Sigma _{\mathrm{NLO}}^{\mathrm{SM}}\). As can be noted, the \(Z_H^{\mathrm{BSM}}\) term factorizes the NLO EW contributions in the SM, while \(C_1\) does not. Indeed, in general, EW loop corrections on top of \(\lambda _3\)-induced effects need a dedicated two-loop calculation and a full-fledged EFT approach in order to obtain UV-finite results; only the \(Z_H^{\mathrm{BSM}}\) contribution is completely model-independent and factorizes the NLO EW corrections in the SM. However, it is worth to note that, assuming factorization also for the \(C_1\) contributions, terms of the order \(\kappa _3 C_1 \times \delta _{\mathrm{EW}}\big |_{{\lambda }_3=0} \) would be anyway negligible, since either \( \delta _{\mathrm{EW}}\big |_{{\lambda }_3=0} \) (Sudakov logarithms in the boosted regime) or \(C_1\) (Sommerfeld enhancement in the threshold region) is sizable, but never both of them at the same time. This will be clear in the differential plots we display in the following.

\(p_T(H)\) (left) and m(ZH) (right) distributions for ZH. Upper plots: \((\sigma _{\mathrm{NLO}}^{\mathrm{BSM}}-\sigma _{\mathrm{LO}})/\sigma _{\mathrm{LO}}\) ratio for different values of \(\kappa _3\). Lower plots: comparison of BSM/SM ratio including or not NLO EW corrections for different values of \(\kappa _3\)

\(p_T(H)\) (left) and m(WH) (right) distributions for WH. Upper plots: \((\sigma _{\mathrm{NLO}}^{\mathrm{BSM}}-\sigma _{\mathrm{LO}})/\sigma _{\mathrm{LO}}\) ratio for different values of \(\kappa _3\). Lower plots: comparison of BSM/SM ratio including or not NLO EW corrections for different values of \(\kappa _3\)

\(p_T(H)\) (left) and \(m(t {\bar{t}} H)\) (right) distributions for \(t {\bar{t}} H\). Upper plots: \((\sigma _{\mathrm{NLO}}^{\mathrm{BSM}}-\sigma _{\mathrm{LO}})/\sigma _{\mathrm{LO}}\) ratio for different values of \(\kappa _3\). Lower plots: comparison of BSM/SM ratio including or not NLO EW corrections for different values of \(\kappa _3\)

The EW K-factor at the inclusive level can be found for all processes in Table 2, while relevant differential results for ZH, WH and \(t {\bar{t}} H\) are displayed in Figs. 8, 9 and 10, respectively. In each figure, plots on the left show the \(p_T(H)\) distributions, while plots on the right those for the invariant mass of the final state. In the upper plots we display the ratio \((\sigma _{\mathrm{NLO}}^{\mathrm{BSM}}-\sigma _{\mathrm{LO}})/\sigma _{\mathrm{LO}}\) for different values of \(\lambda _3\), (\(-10\), 0, 1, 2, 10). In practice, the case \(\lambda _3=1\), directly denoted as SM in the plots, corresponds to the differential \((K_{\mathrm{EW}}-1)\) in the SM. The lower plots display the ratio \(\sigma _{\mathrm{NLO}}^{\mathrm{BSM}}/\sigma _{\mathrm{NLO}}\) (solid lines) and the term \(1 +\delta \Sigma _{\kappa _3}\) (dashed lines) for different values of \(\lambda _3\), (\(-10,0,1,2,10\)). In practice, the former is our prediction at NLO EW accuracy for the signal strengths \(\mu _{i}\) that will enter in the fits of the next section,Footnote 8 the latter is the definition at LO used in previous work.

First, we comment on the shape of the NLO EW corrections in the upper plots. The general trend in the SM is characterized by large negative Sudakov logarithms in the tails, especially for \(p_T(H)\) in VH production, and positive corrections in the threshold region, especially for the invariant mass distributions and in general \(t {\bar{t}} H\). The latter are precisely the effects due to \(C_1\). Thus, changing the value of \(\lambda _3\), the shape of the \(\sigma _{\mathrm{NLO}}^{\mathrm{BSM}}/\sigma _{\mathrm{LO}}\) ratio is highly affected in the threshold region, while it is not deformed in the tail. On the other hand, the change induced by \(\lambda _3\) on \(Z_H^{\mathrm{BSM}}\) results in a constant shift in the tail of the distributions. The small bump around \(p_T(H)\sim m_t\) and \(m(ZH)\sim 2m_t\) in ZH production is simply due to the \(t{{\bar{t}}}\) threshold in diagrams involving a top-quark loop.

By looking at the upper plots in Figs. 8, 9 and 10 is evident that EW corrections have to be included in order to correctly identify anomalous \(\lambda _3\) effects. On the other hand, NLO EW corrections do not largely affect the value of the signal strengths, i.e. the ratio of the BSM and SM prediction. This fact can be seen in the lower plots, where we display \(\sigma _{\mathrm{NLO}}^{\mathrm{BSM}}/\sigma _{\mathrm{NLO}}\) (solid lines) and \(1 +\delta \Sigma _{\kappa _3}\) (dashed lines), which indeed corresponds to the aforementioned ratio with or without NLO EW corrections both in the numerator and denominator.Footnote 9 Solid and dashed lines are in general very close, especially for small values of \(\kappa _3\). It is interesting to note that for very small values of \(m(t {\bar{t}} H)\) a value \(\kappa _\lambda =-10\) would lead to corrections that are negative and larger in absolute value than the LO. This is due to the very large \(C_1\) (see Fig. 5) and points to the necessity of including higher-order \(\lambda _3\)-induced effects for large values of \(\kappa _3\) and for this specific phase-space region.

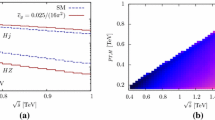

For the case of total cross sections, we plot, in Fig. 11, the ratio \(\sigma _{\mathrm{NLO}}^{\mathrm{BSM}}/\sigma _{\mathrm{NLO}}^{\mathrm{SM}}\) as a function of \(\kappa _3\) in the range [\(-10\), 10] for all the single Higgs production processes, including also tHj. Differences with the corresponding \(1 +\delta \Sigma _{\kappa _3}\) ratios, which have been presented in Ref. [39], are hardly visible and thus we do not show them here.

In conclusion, constraints on \(\lambda _3\) from a global fit based on the value of the signal strengths \(\mu _i\) at inclusive [39] or differential level [40] will not be affected by NLO EW corrections. On the other hand, in the experimental analyses EW corrections have to be taken into account, especially at the differential level, for the determination of the value of the signal strengths, which is in general important for any BSM study and not peculiar for our case.

5 Constraining \(\kappa _3\) through a global fit

In this section we discuss the role of differential distributions in the determination of \(\lambda _3\) via single-Higgs production and decays measurements. The aim of this section is threefold. First, we show that the interplay of theoretical and experimental uncertainties have a large impact in the determination of the constraints on \(\lambda _3\), especially when differential information is exploited. Second, we discuss how bounds on \(\lambda _3\) are affected by the presence of additional anomalous couplings in the fit. In particular, we progressively lift the assumption that the Higgs couplings to the top quark and to vector bosons are SM-like. Third, we include the EW effects discussed in the previous section in the fit analysis, providing consistent formulas for repeating the fit in conjunction with additional Higgs anomalous couplings. The reader who is only interested in the results may wish to go directly to Sect. 5.2 and skip Sect. 5.1, where formulas are given and a few technical details are discussed.

5.1 Combined parameterization of \(\kappa _3\), \(\kappa _t\) and \(\kappa _V\) effects

In order to parametrize the Higgs anomalous couplings to the top quark and to the vector bosons we use the coupling modifiers \(\kappa _t\) and \(\kappa _V\), respectively (see Ref. [7] for definitions). We are interested in how additional BSM effects entering at LO may alter the determination of \(\kappa _3\) and the relevance of differential measurements. The choice of the (\(\kappa _3, \kappa _t, \kappa _V\)) kappa framework is driven by simplicity; our main purpose is to add new degrees of freedom in the fit and identify in which configurations the differential information may be particularly relevant. On the other hand, while the cases of new physics entering only via \(\kappa _3\) and a very general EFT parametrization (ten independent parameters) have already been explored [41], simplified intermediate parameterizations have not been considered yet. These parameterizations, such as the one used here, may be useful to identify relevant scenarios for which the determination of \(\kappa _3\) is feasible.Footnote 10

First of all we extended the framework and the notation introduced in Ref. [39] in order to take into account in the fit differential information, EW corrections in the production, and \(\kappa _t\) and \(\kappa _V\) dependence. The experimental inputs entering the fit are the signal strengths, which are defined for any particular combination \(i \rightarrow H \rightarrow f\) of production and decay channel as

In Eq. (16), the quantities \(\mu _i\) and \(\mu ^f\) are the production cross sections \(\sigma (i)\) (\(i=\) ggF, VBF, WH, ZH, \(t {\bar{t}}H\)) and the \(\mathrm{BR}(f)\) \((f= \gamma \gamma , VV^*,ff)\) divided by their SM values, respectively. Assuming on-shell production, the product \(\mu _i \times \mu ^f\) is the measured rate for the \(i \rightarrow H \rightarrow f\) process divided by the corresponding SM prediction. This is valid also for differential distributions involving the reconstructed momentum of the Higgs boson. For simplicity, in the following we will refer with the symbol \(\sigma \) to both total cross sections or (bins in) differential distributions.

The signal-strength productions \( \mu _i\) are given by

where \(\kappa _{gg \mathrm F} = \kappa _{t {\bar{t}} H} =\kappa _t\) and \(\kappa _{VH} = \kappa _{\mathrm{VBF}} =\kappa _V\) and the effect of \(\kappa _3\) is parameterized via the quantity \(\delta \mu _i(\kappa _3)\). In presence of NLO EW corrections \(\delta \mu _i(\kappa _3) \) is given by

where we have explicitly shown which quantities depend on the specific production process i. For differential distributions, differential \(K_{\mathrm{EW}}\) have to be used. As can be noted, we did not include \(\kappa _t\) and \(\kappa _V\) effects entering at one loop. As we will see in the results of the fit, we are going to probe deviations at the percent level in \(\kappa _t\) and \(\kappa _V\). Thus, \(\kappa _t^2 \kappa _3\) and \(\kappa _V^2 \kappa _3\) effects are negligible for our purposes. On the other hand, terms of order \(\kappa _t^2 \kappa _3^2\) and \(\kappa _V^2 \kappa _3^2\) may be more important and in fact those from the Higgs wave-function can be consistently resummed; they are included in Eq. (17) via the \(Z_H^{\mathrm{BSM}} \kappa _i^2\) term.Footnote 11 However, unless differently specified, we verified that also the inclusion of the \(\kappa _t^2 \kappa _3^2\) and \(\kappa _V^2 \kappa _3^2\) contributions has a negligible impact in the results presented in the following. It is also important to note that any further \(\kappa _t \) or \(\kappa _V\) dependence that may be introduced by NLO EW corrections, on top of those already present at LO, is negligible. Indeed, NLO EW corrections are per se at the percent level and their anomalous \(\kappa _t\) component would be of the order of few percents of the corrections themselves. Thus, these kinds of effects, which similarly to those of order \(\kappa _t^2 \kappa _3^2\) and \(\kappa _V^2 \kappa _3^2\) can actually be calculated only in an EFT framework, are expected to be of the order \(\sim \alpha (\kappa _i -1)\) and therefore at the permille level or even smaller in our analysis. For this reason, we can safely ignore them.

Similarly, the signal strength \(\mu _f\) for the Higgs decays \(H \rightarrow f\) is given by

NLO EW corrections in Higgs decays are small at inclusive level, therefore we can safely ignore them. The partial decay width in a given channel is given by

where \(\Gamma _\mathrm{LO}^{\mathrm{SM}}\) is the total width at LO in the SM. The SM widths \(\Gamma ^{\mathrm{SM}}(f)\) in Eq. (19) can be obtained by setting \(\kappa _3=\kappa _f=1\) in \(\Gamma ^{\mathrm{BSM}}(f)\). In order to ensure that the contribution of the Higgs-wave-function renormalization does not affect the branching ratios, in this case we resummed also the SM part (\( Z_H = 1/(1-\kappa _3^2 \delta Z_H)\)) and factorize it to the \(\kappa _f^2\) dependence, as done in Ref. [39] for the LO analysis. For the \(\gamma \gamma \) decay channel \(\kappa _{\gamma \gamma }\) depends on \(\kappa _t\) and \(\kappa _V\),Footnote 12 \(\kappa _{VV^*}= \kappa _V\) and \(\kappa _{ff} = 1\). Using Eq. (20) the signal strength for the decay becomes

where in the last step we have assumed that \(C_1\) is small, which is indeed true for the decay channels.

5.2 Results: comparison of differential and inclusive information in different scenarios

A first global fit on single Higgs channels has been performed in Ref. [39] using the 8 TeV LHC data, and a similar analysis has been applied to a future LHC scenario (CMS-HL-II) with \(3000~\mathrm{fb}^{-1}\). Only total cross section information was used and especially the fit included only \(\lambda _3\) as a variable. In Ref. [41] a first attempt to use differential rate information provided in Ref. [39] was made by extrapolating the projections on total cross section from ATLAS-HL [55, 56, 70] with \(3000~\mathrm{fb}^{-1}\).

Since no differential information is available in the measured data at the moment, we focus on the same future scenario at 14 TeV (ATLAS-HL) considered in Ref. [41]. However, our results cannot be directly compared with those in Ref. [41], since there are a few differences in the treatment of the inputs from experimental projections. Details are reported in Appendix A, where we also carefully describe the procedure of the fit we performed and the assumptions on the uncertainties. In short, bounds on \(\kappa _3\), \(\kappa _t\) and \(\kappa _V\) are obtained by maximizing a log-likelihood function.

We perform the fit considering two very different scenarios for the uncertainties. In the first scenario (S1), only the statistical uncertainty is included. This crude assumption corresponds to the ideal (and rather unrealistic) situation where theoretical and experimental systematic uncertainties are negligible. On the other hand, we exploit it for a direct comparison with the second scenario (S2), where both theoretical and experimental systematic uncertainties are taken into account. At the differential level we performed the combination of the uncertainties via two different approaches that are described in detail in Appendix A. For this reason differential results for this second scenario always appear as bands rather than lines, accounting the uncertainty related to the different assumptions on the systematic and theoretical errors.

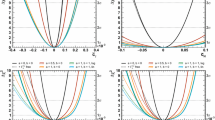

Before performing the global fit, we separately consider the different experimental inputs corresponding to ggF, VBF, VH and \(t {\bar{t}} H\) productionFootnote 13 and we restrict to the configuration with \(\kappa _3\) only (\(\kappa _t=\kappa _V=1\)). We remind the reader that different decay channels are entering for each of the production processes. Results are shown in Fig. 12, where the plot on the left refers to scenario S1 and the plot on the right to scenario S2. For the case of VH and \(t {\bar{t}} H\) production dashed lines correspond to the fit of differential information; details of the binning are reported in Appendix A.

The different shapes of the curves for values smaller and larger than \(\kappa _3=1\) can be understood from the behavior of \(\kappa _3\) and \(\kappa _3^2\) terms in Eqs. (6) and (13). While for \(\kappa _3<1\) both the \(\kappa _3\) and the \(\kappa _3^2\) terms induce negative contributions in the production signal strengths, for \(\kappa _3>1\) there are large cancellations that suppress the effect of \(\kappa _3\). If we only include the statistical uncertainty (S1) the ggF-like channel provides the best constraints for \(\kappa _3\) both for the regions \(\kappa _3>1\) and \(\kappa _3<1\), where also \(t {\bar{t}} H\) is giving strong constraints, which are not improved by the inclusion of differential information. A similar effect is visible also for VH; differential information does not lead to any significant improvement. On the other hand, in the region \(\kappa _3> 1\) we see a clear improvement due to differential information for \(t {\bar{t}} H\), although bounds from this single production process are not sufficient to set a constraint in the region for \(\kappa _3>1\).

The plot on the right (S2) shows that including theoretical and experimental systematic uncertainties makes a difference. The \(t {\bar{t}} H\) process is giving the strongest constraints in the region \(\kappa _3<1\) and receive improvements from the differential information, with a tiny dependence on the assumption made for the combination of the uncertainties. This difference is induced by the change of the ggF result moving from scenario S1 to scenario S2 rather than by an improvement for \(t {\bar{t}} H\). Note, however, that the impact of the differential information for ggF production is not known and, while the exact calculation of the (two-)loop-induced effects from \(\lambda _3\) in \(pp \rightarrow H j\) would be useful, it is currently out of reach. Although constraints from ggF becomes much weaker in scenario S2, in the region \(\kappa _3>1\) they are still the strongest. At variance with ggF, \(t {\bar{t}} H\) is in general very slightly affected by theoretical and systematic uncertainties since the dominant error is of statistical origin. Regarding the bounds on \(\kappa _3\) from VBF-like and VH-like channels, they are always worse than those from ggF and \(t {\bar{t}} H\), even when the differential information is used for VH.

Next, we perform the global fit including all the experimental data as input and taking into account the anomalous couplings \(\kappa _t\) and \(\kappa _V\). In Fig. 13 we present bounds after combining all the production channels, under different assumptions: i) only \(\kappa _3\) is anomalous, ii) \(\kappa _3,\kappa _t\) or \(\kappa _3,\kappa _V\) are anomalous, iii) all three parameters \(\kappa _3,\kappa _V,\kappa _t\) are anomalous. In the presence of anomalous couplings other than \(\kappa _3\), we marginalize over them. The plot on the left refers to scenario S1, only statistical uncertainties, and the one on the right to scenario S2, systematic and theoretical uncertainties included. As we expect, in scenario S1 the differential information (dashed line) does not noticeably improve any of the constraints, while in the scenario S2 in the region \(\kappa _3<1\) and especially in the region \(\kappa _3> 1\) differential information from VH and \(t {\bar{t}} H\) leads to a clear improvement of the constraints. What, instead, is not obvious, especially given the findings of Ref. [41], is the effect induced by anomalous \(\kappa _t\) and/or \(\kappa _V\) terms to the fit. While constraints in the region \(\kappa _3< 1\) are relaxed, although not washed out completely, by the inclusion of one or two new degrees of freedom, in the region \(\kappa _3>1\) they are almost unaltered. In other words, in scenario S2, bounds in the region \(\kappa _3>1\) are more affected by differential information than by the addition of the \(\kappa _t\) or \(\kappa _V\) parameters. Moreover, especially in the region \(\kappa _3<1\), these two parameters alter the \(\kappa _3\) constraints more in the unrealistic scenario S1 than S2. We describe rather in detail the observed features exploiting the information contained in Fig. 12.

In scenario S1 for \(\kappa _3<1\) the constraints are strongly affected by the inclusion of \(\kappa _t\) and/or \(\kappa _V\) since the global fit with only \(\kappa _3\) is completely dominated by ggF in that region. For this process only the total cross-section information is used in the fit, so that a flat direction appears, i.e., the fit is dominated by one input,Footnote 14 which is sufficient for setting constraints on only \(\kappa _3\) but not at the same time on \(\kappa _3\) and \(\kappa _t,\kappa _V\). To resolve this degeneracy, more constraining information must be added to the fit. Indeed, the constraints with two parameters (\(\kappa _3,\kappa _t\) or \(\kappa _3,\kappa _V\)) or three \((\kappa _3, \kappa _t,\kappa _V)\) are in the region of the constraints from VBF and \(t {\bar{t}} H \) in Fig. 12.

The previous argument cannot be applied to the region \(\kappa _3>1\) for scenario S1, where the bounds in the global fit with only \(\kappa _3\) are not completely dominated by ggF. Indeed the \(t {\bar{t}} H\) (and in a smaller way the VBF) contribution is not negligible in that region, as can be seen from the left plot of Fig. 12. Moreover, at variance with ggF production, there is not a large background in \(t {\bar{t}} H\) production for the experimental signatures involving the Higgs to \(\mu ^+ \mu ^-\) decay, whose branching ratio has a different \(\kappa _V\) and \(\kappa _t\) dependence w.r.t. \(\gamma \gamma \) and \(V V^*\) decays, and for values \(\kappa _3\sim 8\) the impact of decays is more relevant. For this reason \(t {\bar{t}} H\) and ggF are sufficient for constraining one, two or three parameters, with negligible difference when parameters other than \(\kappa _3\) are marginalized. We explicitly verified this feature.

Moving to scenario S2, the plot on the right where all uncertainties are included, for \(\kappa _3<1\) the bounds are dominated by \(t {\bar{t}} H\) channel. For this reason there is a smaller dependence on the number of parameters considered in the fit and a larger sensitivity to the differential information, which is present for the same reason also in the region \(\kappa _3> 1\).

It is clear that the role of the ggF is essential when the impact of differential information is investigated in the global fit. When ggF is dominant, since there is no differential dependence, it masks the relevance of differential distributions. On the other hand, when \(t {\bar{t}} H \) is dominant, the differential information becomes relevant. Above all, one should bear in mind that the impact of \(\kappa _3\) on ggF distributions has not been calculated because of technical reasons; the exact two-loop calculation is beyond the current technology, but could be relevant too. To this purpose, in the following we look at constraints in the \((\kappa _3, \kappa _t)\) and \((\kappa _3, \kappa _V)\) plane with and without the contributions from VBF and ggF, which hides the impact of the differential information. We consider only scenario S2, which is more realistic.

In Fig. 14, we provide \(1\sigma \) and \(2\sigma \) contours in \((\kappa _3,\kappa _t)\) plane without (left) and with (right) anomalous \(\kappa _V\), which is anyway marginalized. Upper plots includes all the production channels, whereas in the lower ones only VH and \(t {\bar{t}} H\) enter. Analogous plots are provided in Fig. 15 for the \((\kappa _3,\kappa _V)\), without and with anomalous \(\kappa _t\). First of all, one can note that due to the \(\kappa _t\) dependence of the gluon-fusion channel and \(t {\bar{t}} H\) channel, in the upper plots the constraints on \(\kappa _3\) in presence of \(\kappa _t\) (Fig. 14) are stronger than those in the presence of \(\kappa _V\) (Fig. 15).Footnote 15 Also, in the upper plots, having two independent parameters (left) or marginalizing on an additional third one (right) does not lead to qualitatively significant differences. As also discussed before, the impact of the differential information is more important.

If we consider the lower plots the situation is very different. First, constraints with two or three parameters are qualitatively different. Second, the impact of the distributions is much more relevant. In the lower-left plot of Fig. 15 a flat direction is clearly resolved by differential information. The bottom-line is that by changing the number of free parameters and the number of inputs entering in the fit, the relevance of differential distributions and the sensitivity of the \(\kappa _3\)-limits on additional parameters can be considerably altered. The range of the lower plots is much larger than in the upper plots; for this reason the exclusion of \(\kappa _3^2 \kappa _t^2\) and/or \(\kappa _3^2 \kappa _V^2\) terms from Eq. (17) would lead to visible effects to the 2\(\sigma \) contours, anyway without altering the qualitative information.

6 Conclusion

We have studied one-loop \(\lambda _3\) effects for all the relevant single Higgs production modes at the LHC (\(gg\mathrm{F}\), \(\mathrm{VBF}\), VH, \(t{\bar{t}}H\), tHj) and decays (\(\gamma \gamma \), \(VV^*\), ff, gg), extending and completing the results presented in Ref. [39]. In particular, we have calculated differential results for VBF, VH, \(t {\bar{t}} H\) and tHj production and \(H\rightarrow 4\ell \) decay. We have developed an automated code, which has been made public, for generating events including one-loop \(\lambda _3\) effects. All the distributions that may be potentially affected by anomalous values of \(\lambda _3\) have been scrutinized: differential level results for \(t {\bar{t}} H\) production, \(H\rightarrow 4\ell \) decay and also for the tHj process have been presented here for the first time.

We find that the production modes with a large kinematic dependence on \(\lambda _3\) are VH, \(t {\bar{t}} H\) and tHj. In particular, VH and \(t {\bar{t}} H\) can provide additional sensitivity on \(\lambda _3\) at differential level. For these two channels we have consistently combined complete SM NLO EW corrections with anomalous \(\lambda _3\)-induced effects at differential level. The same combination has been performed, at inclusive level, also for all the other production processes. We have verified the robustness of our strategy: NLO EW corrections are essential for a precise determination of anomalous \(\lambda _3\) effects, but they do not jeopardize the efficiency of indirect \(\lambda _3\) determination. We note that NLO EW corrections to tHj in the SM were unknown and have been calculated for the first time too.

Finally, we have performed a fit for \(\kappa _3\) based on the future projections of ATLAS-HL for single-Higgs production and decay at 14 TeV [55, 56]. We have considered the effects induced on the fit by additional degrees of freedom, in particular, anomalous Higgs couplings with the vector bosons and/or the top quark. We have found that, in a global fit, including all the possible production and decay channels, two additional degrees of freedom such as those considered here do not preclude the possibility of setting sensible \(\lambda _3\) bounds, especially, they have a tiny impact on the upper bound for positive \(\lambda _3\) values. On the contrary, the role of differential information may be relevant, critically depending on the assumptions on the future experimental and theoretical uncertainties. We have also shown that the relevance of differential distributions and the sensitivity on \(\kappa _3\) can be considerably altered by varying the relation among the number of free parameters and the number of inputs entering in the fit.

Our results clearly illustrate the complementarity of precise single-Higgs measurements and double Higgs searches at the LHC for constraining \(\lambda _3\) with the current and future accumulated luminosity. We therefore encourage experimental collaborations to use the MC tool provided here for performing \(\lambda _3\) determination via single Higgs measurements, taking into account all the possible correlations among theoretical and experimental uncertainties of the different production and decay channels.

Notes

The impact of differential distributions in gluon fusion is not studied here as one would need to consider the effects of the trilinear coupling in \(H+1\) jet. This involves the calculation of \(2\rightarrow 2\) two-loop amplitude with four independent scales, which is not yet feasible.

The code can be found at the webpage: https://cp3.irmp.ucl.ac.be/projects/madgraph/wiki/HiggsSelfCoupling.

To the best of our knowledge, NLO EW corrections to the tHj process are calculated for the first time here.

As the weak loops considered here are always characterized by scales of the order of the mass of the heavy particles in the propagators (weak bosons, top quarks and the Higgs) while QCD corrections at threshold are typically dominated by lower scales, factorization is a reasonable working assumption.

As discussed in Ref. [39], the choice of the factorization scale has a negligible effects on \(C_1\) at inclusive level. The effect is even smaller at differential level.

In the EW sector of the SM all the interactions are determined by the mass of the fermions, \(m_H\) and three additional parameters, which are typically \(m_W\), \(m_Z\) and \(\alpha \) or \(G_\mu \). In general, it is not possible to alter at NLO EW accuracy a derived quantity, such as \(\lambda =m_H^2/(2 v^2)\), without spoiling the renormalizability of the theory. The special case of \(\lambda _3\) in single Higgs production at one loop has been discussed in detail in Refs. [39, 42].

Here, in order to keep the notation simple, with the symbol \(\delta Z_H\) we still refer to only the \(\lambda _3\) contributions to the Higgs-wave-function counterterm. Thus, \(\delta _{\mathrm{EW}}\big |_{{\lambda }_3=0}\) contains further contributions to the Higgs-wave-function counterterm that do not depend on \(\lambda _3\).

The signal strengths \(\mu _{i}\) is better defined afterwards in Eq. (17). In this section \(\kappa _i=1\).

Actually, the ratio without NLO EW corrections should be \(\sigma _\mathrm{\lambda _3}^{\mathrm{BSM}}/\sigma _\mathrm{\lambda _3}^{\mathrm{SM}}\), but its difference with \(1 +\delta \Sigma _{\kappa _3}\), which is used in previous work and more useful for a direct comparison, is negligible.

In fact, the analysis carried here is a particular choice of two (linear combinations) of the 10 Wilson coefficients identified in Ref. [41]: \(\kappa _t\) is related to \(\delta y_t\) and \(\kappa _V\) to \(c_W=c_Z\).

Equation (18) can be in principle generalized to an EFT framework. In that case, EW corrections can be performed also on top of new-physics effects entering at the tree level as well as a \(\kappa _3\)-induced correction. However, the latter involves non-trivial higher-dimensional corrections.

The relevant expression is

$$\begin{aligned} \kappa _{\gamma \gamma } = \frac{|\kappa _V A_1(\tau _W)+ \kappa _t \frac{4}{3}A_{1/2}(\tau _t)|}{|A_1(\tau _W)+ \frac{4}{3}A_{1/2}(\tau _t) |} , \end{aligned}$$where the functions \(A_1(\tau _W)\) and \(A_{1/2}(\tau _t)\) are defined in Ref. [69].

In this section when we refer to a production mode X in fact we mean one of the different X-like categories in Table 3. As can be seen, in any X-like category the contribution of the actual X process is in general dominant, so we can refer directly to it on the text for simplicity. Only the VBF-like category receives a non-negligible contribution from ggF, which on the other hand has a \(C_1\) very similar to VBF.

Note we have three decay channels for ggF that are almost fully controlled by \(k_V\), namely \(WW^*, VV\) and \(\gamma \gamma \). Indeed, also for \(H\rightarrow \gamma \gamma \) the contribution from top-quark loop is known to be much smaller than W-loop contribution.

For the same reason, comparing these results with those that would be obtained in scenario S1, one may also find that after including all uncertainties, the bounds on \(\kappa _t\) are enlarged more significantly than those on \(\kappa _V\), since the dominant contribution to the bounds on \(\kappa _t\) is ggF and \(t {\bar{t}} H\), and the experimental systematic uncertainty and theoretical uncertainty are much larger than statistical uncertainty for ggF.

References

ATLAS Collaboration, G. Aad et al.,Observation of a new particle in the search for the StandardModel Higgs boson with the ATLAS detector at the LHC. Phys. Lett. B 716, 1–29 (2012). arXiv:1207.7214 [hep-ex]

CMS Collaboration, S. Chatrchyan et al., Observation of a new boson at a mass of 125 GeV with the CMS experiment at the LHC. Phys. Lett. B 716, 30–61 (2012). arXiv:1207.7235 [hep-ex]

CMS Collaboration, V. Khachatryan et al., Search for the associated production of the Higgs boson with a top-quark pair. JHEP 09, 087 (2014). arXiv:1408.1682 [hep-ex]. [Erratum: JHEP 10,106(2014)]

ATLAS Collaboration, G. Aad et al., Search for \(H \rightarrow \gamma \gamma \) produced in association with top quarks and constraints on the Yukawa coupling between the top quark and the Higgs boson using data taken at 7 TeV and 8 TeV with the ATLAS detector. Phys. Lett. B 740, 222–242 (2015). arXiv:1409.3122 [hep-ex]

ATLAS Collaboration, G. Aad et al., Search for the associated production of the Higgs boson with a top quark pair in multilepton final states with the ATLAS detector. Phys. Lett. B 749, 519–541 (2015). arXiv:1506.05988 [hep-ex]

ATLAS Collaboration, G. Aad et al., Search for the Standard Model Higgs boson produced in association with top quarks and decaying into \(b\bar{b}\) in pp collisions at \(\sqrt{s}\)= 8 TeV with the ATLAS detector. Eur. Phys. J. C 75 (7), 349 (2015). arXiv:1503.05066 [hep-ex]

ATLAS, CMS Collaboration, G. Aad et al., Measurements of the Higgs boson production and decay rates and constraints on its couplings from a combined ATLAS and CMS analysis of the LHC pp collision data at \(\sqrt{s}\) = 7 and 8 TeV. JHEP 08, 045 (2016). arXiv:1606.02266 [hep-ex]

F. Maltoni, E. Vryonidou, M. Zaro, Top-quark mass effects in double and triple Higgs production in gluon-gluon fusion at NLO. JHEP 11, 079 (2014). arXiv:1408.6542 [hep-ph]

D. de Florian, J. Mazzitelli, Higgs pair production at next-to-next-to-leading logarithmic accuracy at the LHC. JHEP 09, 053 (2015). arXiv:1505.07122 [hep-ph]

S. Borowka, N. Greiner, G. Heinrich, S. Jones, M. Kerner, J. Schlenk, U. Schubert, and T. Zirke, Higgs Boson Pair Production in Gluon Fusion at Next-to-Leading Order with Full Top-Quark Mass Dependence. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117 (1), 012001 (2016). arXiv:1604.06447 [hep-ph]. [Erratum: Phys. Rev. Lett. 117(7), 079901 (2016)]

C. Anastasiou, C. Duhr, F. Dulat, E. Furlan, T. Gehrmann, F. Herzog, A. Lazopoulos, B. Mistlberger, High precision determination of the gluon fusion Higgs boson cross-section at the LHC. JHEP 05, 058 (2016). arXiv:1602.00695 [hep-ph]

U. Baur, T. Plehn, and D. L. Rainwater, Probing the Higgs selfcoupling at hadron colliders using rare decays. Phys. Rev. D 69, 053004 (2004). arXiv:hep-ph/0310056 [hep-ph]

J. Baglio, A. Djouadi, R. Grber, M.M. Mhlleitner, J. Quevillon, M. Spira, The measurement of the Higgs self-coupling at the LHC: theoretical status. JHEP 04, 151 (2013). arXiv:1212.5581 [hep-ph]

W. Yao, Studies of measuring Higgs self-coupling with \(HH\rightarrow b{\bar{b}} \gamma \gamma \) at the future hadron colliders. in Proceedings, 2013 Community Summer Study on the Future of U.S. Particle Physics: Snowmass on the Mississippi (CSS2013): Minneapolis, MN, USA, July 29-August 6, 2013 (2013). arXiv:1308.6302 [hep-ph]. https://inspirehep.net/record/1251544/files/arXiv:1308.6302.pdf

V. Barger, L.L. Everett, C.B. Jackson, G. Shaughnessy, Higgs-Pair Production and Measurement of the Triscalar Coupling at LHC(8, 14). Phys. Lett. B 728, 433–436 (2014). arXiv:1311.2931 [hep-ph]

A. Azatov, R. Contino, G. Panico, M. Son, Effective field theory analysis of double Higgs boson production via gluon fusion. Phys. Rev. D 92(3), 035001 (2015). arXiv:1502.00539 [hep-ph]

C.-T. Lu, J. Chang, K. Cheung, J.S. Lee, An exploratory study of Higgs-boson pair production. JHEP 08, 133 (2015). arXiv:1505.00957 [hep-ph]

M.J. Dolan, C. Englert, M. Spannowsky, Higgs self-coupling measurements at the LHC. JHEP 10, 112 (2012). arXiv:1206.5001 [hep-ph]

A. Papaefstathiou, L.L. Yang, J. Zurita, Higgs boson pair production at the LHC in the \(b {\bar{b}} W^+ W^-\) channel. Phys. Rev. D 87(1), 011301 (2013). arXiv:1209.1489 [hep-ph]

D.E. Ferreira de Lima, A. Papaefstathiou, M. Spannowsky, Standard model Higgs boson pair production in the (\( b\overline{b} )(b\overline{b} )\) final state. JHEP 08, 030 (2014). arXiv:1404.7139 [hep-ph]

D. Wardrope, E. Jansen, N. Konstantinidis, B. Cooper, R. Falla, N. Norjoharuddeen, Non-resonant Higgs-pair production in the \( b\overline{b} b\overline{b} \) final state at the LHC. Eur. Phys. J. C 75(5), 219 (2015). arXiv:1410.2794 [hep-ph]

J.K. Behr, D. Bortoletto, J.A. Frost, N.P. Hartland, C. Issever, J. Rojo, Boosting Higgs pair production in the \(b{\bar{b}}b{\bar{b}}\) final state with multivariate techniques. Eur. Phys. J. C 76(7), 386 (2016). arXiv:1512.08928 [hep-ph]

C. Englert, F. Krauss, M. Spannowsky, J. Thompson, Di-Higgs phenomenology in \(t\bar{t}hh\): the forgotten channel. Phys. Lett. B 743, 93–97 (2015). arXiv:1409.8074 [hep-ph]

T. Liu and H. Zhang, Measuring Di-Higgs Physics via the \(t \bar{t} hh \rightarrow t \bar{t} b {\bar{b}}b{\bar{b}}\) Channel. arXiv:1410.1855 [hep-ph]

Q.-H. Cao, Y. Liu, B. Yan, Measuring trilinear Higgs coupling in WHH and ZHH productions at the high-luminosity LHC. Phys. Rev. D 95(7), 073006 (2017). arXiv:1511.03311 [hep-ph]

T. Plehn and M. Rauch, The quartic higgs coupling at hadron colliders. Phys. Rev. D 72, 053008 (2005). arXiv:hep-ph/0507321 [hep-ph]

T. Binoth, S. Karg, N. Kauer, and R. Ruckl, Multi-Higgs boson production in the Standard Model and beyond. Phys. Rev. D 74, 113008(2006). arXiv:hep-ph/0608057 [hep-ph]

D. de Florian, J. Mazzitelli, Two-loop corrections to the triple Higgs boson production cross section. JHEP 02, 107 (2017). arXiv:1610.05012 [hep-ph]

C.-Y. Chen, Q.-S. Yan, X. Zhao, Y.-M. Zhong, Z. Zhao, Probing triple-Higgs productions via 4b2 decay channel at a 100 TeV hadron collider. Phys. Rev. D 93(1), 013007 (2016). arXiv:1510.04013 [hep-ph]

W. Kilian, S. Sun, Q.-S. Yan, X. Zhao, Z. Zhao, New Physics in multi-Higgs boson final states. JHEP 06, 145 (2017). arXiv:1702.03554 [hep-ph]

B. Fuks, J.H. Kim, S.J. Lee, Scrutinizing the Higgs quartic coupling at a future 100 TeV protonproton collider with taus and b-jets. Phys. Lett. B 771, 354–358 (2017). arXiv:1704.04298 [hep-ph]

CMS Collaboration, Search for Higgs boson pair production in the final state containing two photons and two bottom quarks in proton-proton collisions at \(\sqrt{\{}s\}=13\sim {{\rm TeV}}\). Tech. Rep. CMS-PAS-HIG-17-008, 2017

ATLAS Collaboration, Search for pair production of Higgs bosons in the \(b\bar{b}b\bar{b}\) final state using proton-proton collisions at \(\sqrt{s}=13\sim {{\rm TeV}}\) with the ATLAS detector. Tech. Rep. ATLAS-CONF-2016-049, 2016

CMS Collaboration, Search for pair production of Higgs bosons in the two tau leptons and two bottom quarks final state using proton-proton collisions at \(\sqrt{s}=13\sim {{\rm TeV}}\). Tech. Rep. CMS-PAS-HIG-17-002, 2017

CMS Collaboration, V. Khachatryan et al., Search for two Higgs bosons in final states containing two photons and two bottom quarks in proton-proton collisions at 8 TeV. Phys. Rev. D 94(5), 052012 (2016). arXiv:1603.06896 [hep-ex]

ATLAS Collaboration, Prospects for measuring Higgs pair production in the channel \(H(\rightarrow \gamma \gamma )H(\rightarrow b\overline{b})\) using the ATLAS detector at the HL-LHC. Tech. Rep. ATL-PHYS-PUB-2014-019, CERN, Geneva, Oct, 2014. http://cds.cern.ch/record/1956733

M. McCullough, An Indirect Model-Dependent Probe of the Higgs Self-Coupling. Phys. Rev. D 90(1), 015001 (2014). arXiv:1312.3322 [hep-ph]. [Erratum: Phys. Rev. D92(3), 039903 (2015)]

M. Gorbahn, U. Haisch, Indirect probes of the trilinear Higgs coupling: \(gg \rightarrow h\) and \(h \rightarrow \gamma \gamma \). JHEP 10, 094 (2016). arXiv:1607.03773 [hep-ph]

G. Degrassi, P. P. Giardino, F. Maltoni, and D. Pagani, Probing the Higgs self coupling via single Higgs production at the LHC. JHEP 12, 080 (2016). arXiv:1607.04251 [hep-ph]

W. Bizon, M. Gorbahn, U. Haisch, G. Zanderighi, Constraints on the trilinear Higgs coupling from vector boson fusion and associated Higgs production at the LHC. JHEP 07, 083 (2017). arXiv:1610.05771 [hep-ph]

S. Di Vita, C. Grojean, G. Panico, M. Riembau, and T. Vantalon, A global view on the Higgs self-coupling. arXiv:1704.01953 [hep-ph]

G. Degrassi, M. Fedele, P.P. Giardino, Constraints on the trilinear Higgs self coupling from precision observables. JHEP 04, 155 (2017). arXiv:1702.01737 [hep-ph]

G.D. Kribs, A. Maier, H. Rzehak, M. Spannowsky, P. Waite, Electroweak oblique parameters as a probe of the trilinear Higgs boson self-interaction. Phys. Rev. D 95(9), 093004 (2017). arXiv:1702.07678 [hep-ph]

J. Alwall, R. Frederix, S. Frixione, V. Hirschi, F. Maltoni, O. Mattelaer, H.S. Shao, T. Stelzer, P. Torrielli, M. Zaro, The automated computation of tree-level and next-to-leading order differential cross sections, and their matching to parton shower simulations. JHEP 07, 079 (2014). arXiv:1405.0301 [hep-ph]

M. L. Ciccolini, S. Dittmaier, and M. Kramer, Electroweak radiative corrections to associated WH and ZH production at hadron colliders. Phys. Rev. D 68, 073003 (2003). arXiv:hep-ph/0306234 [hep-ph]

A. Denner, S. Dittmaier, S. Kallweit, A. Muck, Electroweak corrections to Higgs-strahlung off W/Z bosons at the Tevatron and the LHC with HAWK. JHEP 03, 075 (2012). arXiv:1112.5142 [hep-ph]

F. Granata, J.M. Lindert, C. Oleari, S. Pozzorini, NLO QCD+EW predictions for HV and HV +jet production including parton-shower effects. JHEP 09, 012 (2017). arXiv:1706.03522 [hep-ph]

S. Frixione, V. Hirschi, D. Pagani, H.S. Shao, M. Zaro, Weak corrections to Higgs hadroproduction in association with a top-quark pair. JHEP 09, 065 (2014). arXiv:1407.0823 [hep-ph]

S. Frixione, V. Hirschi, D. Pagani, H.S. Shao, M. Zaro, Electroweak and QCD corrections to top-pair hadroproduction in association with heavy bosons. JHEP 06, 184 (2015). arXiv:1504.03446 [hep-ph]

Y. Zhang, W.-G. Ma, R.-Y. Zhang, C. Chen, L. Guo, QCD NLO and EW NLO corrections to \(t\bar{t}H\) production with top quark decays at hadron collider. Phys. Lett. B 738, 1–5 (2014). arXiv:1407.1110 [hep-ph]

J. R. Andersen et al., Les Houches 2015: Physics at TeV Colliders Standard Model Working Group Report. in 9th Les Houches Workshop on Physics at TeV Colliders (PhysTeV 2015) Les Houches, France, June 1-19, 2015. 2016. arXiv:1605.04692 [hep-ph]. http://lss.fnal.gov/archive/2016/conf/fermilab-conf-16-175-ppd-t.pdf

D. Pagani, I. Tsinikos, M. Zaro, The impact of the photon PDF and electroweak corrections on \(t\bar{t}\) distributions. Eur. Phys. J. C 76(9), 479 (2016). arXiv:1606.01915 [hep-ph]

R. Frederix, S. Frixione, V. Hirschi, D. Pagani, H.-S. Shao, M. Zaro, The complete NLO corrections to dijet hadroproduction. JHEP 04, 076 (2017). arXiv:1612.06548 [hep-ph]

M. Czakon, D. Heymes, A. Mitov, D. Pagani, I. Tsinikos, and M. Zaro, Top-pair production at the LHC through NNLO QCD and NLO EW. arXiv:1705.04105 [hep-ph]

ATLAS Collaboration, Projections for measurements of Higgs boson cross sections, branching ratios and coupling parameters with the ATLAS detector at a HL-LHC. Tech. Rep. ATL-PHYS-PUB-2013-014, CERN, Geneva, Oct, 2013. https://cds.cern.ch/record/1611186

ATLAS Collaboration, HL-LHC projections for signal and background yield measurements of the \(H\rightarrow \gamma \gamma \) when the Higgs boson is produced in association with \(t\) quarks, W or Z bosons. Tech. Rep. ATL-PHYS-PUB-2014-012, CERN, Geneva, Jul, 2014. https://cds.cern.ch/record/1741011

L. Di Luzio, R. Grber, and M. Spannowsky, Maxi-sizing the trilinear Higgs self-coupling: how large could it be?. arXiv:1704.02311 [hep-ph]

T. Hahn and M. Perez-Victoria, Automatized one loop calculations in four-dimensions and D-dimensions. Comput. Phys. Commun. 118, 153–165 (1999). arXiv:hep-ph/9807565 [hep-ph]

C. Degrande, C. Duhr, B. Fuks, D. Grellscheid, O. Mattelaer, T. Reiter, UFO - The Universal FeynRules Output. Comput. Phys. Commun. 183, 1201–1214 (2012). arXiv:1108.2040 [hep-ph]

V. Hirschi, R. Frederix, S. Frixione, M.V. Garzelli, F. Maltoni, R. Pittau, Automation of one-loop QCD corrections. JHEP 05, 044 (2011). arXiv:1103.0621 [hep-ph]

R. Frederix, S. Frixione, F. Maltoni, T. Stelzer, Automation of next-to-leading order computations in QCD: The FKS subtraction. JHEP 10, 003 (2009). arXiv:0908.4272 [hep-ph]

LHC Higgs Cross Section Working Group Collaboration, D. de Florian et al., Handbook of LHC Higgs Cross Sections: 4. Deciphering the Nature of the Higgs Sector. arXiv:1610.07922 [hep-ph]

LHC Higgs Cross Section Working Group Collaboration, J. R. Andersen et al., Handbook of LHC Higgs Cross Sections: 3. Higgs Properties. arXiv:1307.1347 [hep-ph]

F. Maltoni, K. Paul, T. Stelzer, and S. Willenbrock, Associated production of Higgs and single top at hadron colliders. Phys. Rev. D 64, 094023 (2001). arXiv:hep-ph/0106293 [hep-ph]

S. Biswas, E. Gabrielli, B. Mele, Single top and Higgs associated production as a probe of the Htt coupling sign at the LHC. JHEP 01, 088 (2013). arXiv:1211.0499 [hep-ph]

M. Farina, C. Grojean, F. Maltoni, E. Salvioni, A. Thamm, Lifting degeneracies in Higgs couplings using single top production in association with a Higgs boson. JHEP 05, 022 (2013). arXiv:1211.3736 [hep-ph]

F. Demartin, F. Maltoni, K. Mawatari, M. Zaro, Higgs production in association with a single top quark at the LHC. Eur. Phys. J. C 75(6), 267 (2015). arXiv:1504.00611 [hep-ph]

A. Denner, Techniques for calculation of electroweak radiative corrections at the one loop level and results for W physics at LEP-200. Fortsch. Phys. 41, 307–420 (1993). arXiv:0709.1075 [hep-ph]

A. Djouadi, The Anatomy of electro-weak symmetry breaking. I: The Higgs boson in the standard model. Phys. Rept. 457, 1–216 (2008). arXiv:hep-ph/0503172 [hep-ph]

ATLAS Collaboration, Prospects for the study of the Higgs boson in the VH(bb) channel at HL-LHC. Tech. Rep. ATL-PHYS-PUB-2014-011, CERN, Geneva, Jul, 2014. http://cds.cern.ch/record/1740962

Acknowledgements