Abstract

We present an exact static, spherically symmetric black hole solution to the third-order Lovelock gravity with a string cloud background in seven dimensions for the special case when the second- and third-order Lovelock coefficients are related via \(\tilde{\alpha }^2_2=3\tilde{\alpha }_3\;(\equiv \alpha ^2)\). Further, we examine thermodynamic properties of this black hole to obtain exact expressions for mass, temperature, heat capacity and entropy, and also perform the thermodynamic stability analysis. We see that a string cloud background has a profound influence on the horizon structure, thermodynamic properties, and the stability of black holes. Interestingly the entropy of the black hole is unaffected due to the string cloud background. However, the critical solution for thermodynamic stability is affected by the string cloud background.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Black holes by quantum results show that they radiate due to the Hawking effect [1]. In the absence of established theories of quantum gravity, black holes have become a major playground to divulge quantum gravity effects through their thermodynamics. Black holes have been used as theorists’ laboratories in many other relevant fields. Thermodynamic properties of black holes have been studied for many years, but well-established statistical explanations of black hole thermodynamics are still lacking. One shows that black holes have the standard thermodynamic quantities, such as temperature, entropy, and heat capacity and so on, and they even possess abundant phase structures like the Hawking–Page phase transition [2] and similar critical phenomena to ordinary thermodynamic systems.

Recent years have witnessed renewed interest in the study of black hole solutions, specially in modified theories of gravity [3, 4]; besides theoretical results, cosmological evidence, e.g. dark matter and dark energy, suggests the possibility of changing Einstein gravity. On the other hand, Einstein gravity cannot be quantized (it is non-renormalizable), so it is believed that it is a low energy effective theory and could be modified with higher derivative terms at high energy [5]. Modifications to Einstein gravity theory, for instance Lovelock theory [3], the f(R) gravity theory [4], etc. have been studied extensively. Those models in higher spacetime dimensions have very different features. For example, the nature of stability in higher dimensions is quite different. Extending the spacetime dimensionality in gravity theories has been one possible way to combine other interactions with gravity or often seems to be even required in many theories, e.g. Kaluza–Klein theory, string theory, brane world scenarios, etc. [6].

In these contexts, apart from the standard Einstein–Hilbert action, there also exist interesting theories of gravity in dimensions greater than four involving higher powers of the curvatures such that the field equations for the metric are at most in second order. Among the higher curvature gravity theories, the most extensively studied theory is the so-called Lovelock gravity [3], which naturally emerges when we wish to generalize the Einstein theory in higher dimensions by keeping all characteristics of the usual general relativity except for the linear dependence of the Riemann tensor. Lovelock gravity is one of the most general second-order theories in higher dimensions, which is free from ghosts. Lovelock theory may play an important role in a string theory where the low energy effective field theory of gravity contains higher curvature terms.

In this sense Lovelock gravity [3] is a natural extension to Einstein gravity. It is constructed by a sum of all the Euler densities of a 2n-dimensional manifold. The Lagrangian is given by

where

The spacetime dimension D can be written as \(D=2t+2\) for even dimensions and \(D=2t+1\) for odd dimensions. The nth-order higher derivative terms \(\mathcal {L}_{n}\) become a surface term when \(D\le 2n\). Non-trivial extra terms contribute to the equations of motion in higher dimensions but not in dimensions less than or equal to 2n. Moreover, higher derivative terms can cancel a ghost term. For instance, Ref. [7] shows that the second-order Lovelock (Gauss–Bonnet) terms cancel a ghost term. Boulware and Deser [8–10] first found a static, spherically symmetric black hole solution with the Gauss–Bonnet corrections. Using Gauss–Bonnet gravity, static, spherically symmetric solutions were obtained later [11, 12] with thermodynamic properties [13]. Static, spherically symmetric black hole solutions in Lovelock gravity with general energy-momentum tensors in any arbitrary dimension can be found in [14] and [15–22] and its thermodynamics in [23]. Further extensive studies of Gauss–Bonnet black holes with a focus on the thermodynamic properties have been found in [24, 25]. The special third-order Lovelock gravity also received significant attention, e.g. for a black hole solution and its thermodynamics in this theory with a Born–Infeld source [26, 27] and for causality violation [28]. Also, the topological properties of general Lovelock black holes in the context of thermodynamics have been investigated [29].

In this paper, we begin with finding static, spherically symmetric black hole solutions for a string cloud background for a specific case, i.e., \(\tilde{\alpha }^2_2=3\tilde{\alpha }_3\), and examine thermodynamic properties in third-order Lovelock gravity. The solution can be utilized to calculate the mass, temperature, entropy, and heat capacity of black holes and explicitly study the effects of a string cloud background. It turns out that the horizon and thermodynamic properties of a Lovelock black hole in conjunction with a string parameter could have some interesting features. It may be pointed out that gravity coupled to clouds of strings may be very useful and important as the Universe can be considered as a collection of extended objects, like one dimensional strings. The study of black holes in a cloud of strings was initiated by Letelier, modifying the Schwarzschild solutions for a cloud of strings as a source [30], which was recently extended to Gauss–Bonnet gravity [31] and also to Lovelock gravity [32, 33]. We show that a string cloud background has a profound influence on horizon structures and the thermodynamic quantities, but entropy is not changed.

The paper is organized as follows: in Sect. 2 we begin by examining the third-order Lovelock action, which is a modification of the Einstein–Hilbert action, and also we derive the energy-momentum tensors of a cloud of strings. The thermodynamics of a static, spherically symmetric black hole solution in this theory is explored in Sect. 5. Before doing so, we find an exact static, spherically symmetric black hole solution in Sect. 4. The paper ends in Sect. 6, which gives concluding remarks. We have used units that fix \(G=c=1\) and the metric signature, \((-,+,+,\cdots ,+)\).

2 Lovelock action and equations of motion

Lovelock theory is the most general theory of gravity that gives second-order field equations in arbitrary dimensions. The recent interest in Lovelock theory arose because its action appears as a low energy limit of a heterotic superstring theory. The simplest third-order Lovelock action reads [3]

where \(\mathcal {I}_{S}\) is a matter action due to a cloud of strings. The Einstein term \( \mathcal {L}_1\) is R, the second-order Lovelock (Gauss–Bonnet) term \(\mathcal {L}_{GB}\) is

and the third-order Lovelock Lagrangian is

Here R, \(R_{\mu \nu \gamma \delta }\), and \(R_{\mu \nu }\) are the Ricci scalar, and the Riemann and the Ricci tensors, respectively. The coupling constants \(\alpha _2\) and \(\alpha _3\) in Eq. (3) have dimensions \([\text {length}]^{4-D}\) and \([\text {length}]^{6-D}\), respectively, and they will help us to explicitly bring about changes in the general relativity equations. In the limits \((\alpha _2,\alpha _3) \rightarrow 0\), one recovers the Einstein–Hilbert action. The variation of the action with respect to the metric \(g_{\mu \nu }\) yields modified field equations for third-order Lovelock gravity,

where \(G_{\mu \nu }^{E}\) is the Einstein tensor, while \(G_{\mu \nu }^{GB}\) and \(G_{\mu \nu }^{\left( 3\right) }\) are given explicitly in [34–39], respectively:

and

\(T_{\mu \nu }\) is the energy-momentum tensor of the matter field which we consider here as clouds of strings. Note that for third-order Lovelock gravity, the non-trivial third terms require the spacetime dimension D to satisfy \( D \ge 7 \).

2.1 Energy-momentum tensor

Next we turn attention to the calculation of the energy-momentum tensor of a cloud of strings (see [30] for further details). The Nambu–Goto action of a string evolving in spacetime is given by

with the Lagrangian for a cloud of strings [30]:

The string worldsheet is associated with a bivector of the form

where \(\epsilon ^{a b}\) is the two-dimensional Levi-Civita tensor and \(\epsilon ^{0 1} = - \epsilon ^{1 0} = 1\). Here \(m>0\) is a constant for each string and \(\gamma \) is the determinant of an induced metric on the string world sheet \(\Sigma \) given by

\((\lambda ^{0}, \lambda ^{1})\), with \(\lambda ^{0}\) and \(\lambda ^{1}\) a timelike and a spacelike parameter, respectively, is a parametrization of the world sheet \(\Sigma \), [40]. Further, since \(T^{\mu \nu } = -2 \partial \mathcal {L}/\partial g^{\mu \nu }\), the energy-momentum tensor for one string reads

Hence, a cloud of strings has the energy-momentum tensor

where \(\rho \) is a proper density of a cloud of strings. The quantity \(\rho \; (-\gamma )^{-1/2} \) is a gauge-invariant density.

3 Effect of string cloud

As will be seen in the following discussions the presence of a string cloud plays a major role in the horizon structure of the theory together with other parameters. For instance, the string cloud parameter a can change the number of horizons and singularities and render a singularity covered by a horizon with the other parameters fixed. Given the parameters \((\alpha ,a)\) a positive mass condition imposes either a mass bound or a range of the horizon radius. Rich analysis along this line as regards the absence of an energy-momentum tensor has been made in [27]. A vanishing string cloud is a transition point for singularities to be created, \(\alpha >0\), and for the number of horizons for \(\alpha <0\). In general the energy-momentum tensor \(T^\mu _\nu \) is expressed for a static, spherically symmetric spacetime,

where k is a constant, [41]. The dominant energy condition allows only \(a\le 0\) and \(-1\le k\le 0\) and the causality condition further constrains k to \(-1\le k\le -\frac{1}{n}\) [41]. Thermodynamic quantities are determined by the mass expression, which is given for Lovelock theory in terms of the horizon radius \(r_h\) by

where \(\xi \equiv \frac{n}{16\pi }2\pi ^{(n+1)/2}/\Gamma [(n + 1)/2]\) and the curvature constant \(\kappa =-1,0,1\) [42]. The mass for a string cloud is

As noticed the string cloud contributes to the mass with the highest possible power of \(r_h\), i.e. the upper bound for the energy condition is \(k=0\) but it violates causality. For even dimensions the presence of a string cloud effectively changes the highest coupling \(\alpha _m\), \(m=2n\), while for odd dimensions it is a unique source term thermodynamically [42].

In this paper we take a string cloud only as a classical background. Reference [28] claims that causality violation in the third-order Lovelock theory can be fixed by adding an infinite tower of massive higher spin particles. Unless we look for a dynamical instead of a static background of strings, it is not certain how a string cloud contributes to the causality problem. However, it is worthwhile to study whether causality violation in the classical sense can be weakened or removed when the external massive particles are combined with a string cloud into a background.

4 Spherically symmetric solution in Lovelock gravity

Here we wish to obtain static, spherically symmetric black hole solutions to Eq. (6) for the energy-momentum tensors, Eq. (12), and investigate their horizons and thermodynamic properties. Hence, we assume the metric to be of the form

where \( \tilde{\gamma }_{ij} \) is the metric of a \((D-2)\)-dimensional constant curvature space \(\kappa = 1,\; 0 \;\) or -1, representing spherical, flat, and hyperbolic spaces, respectively. But in this paper we shall confine ourselves to \(\kappa = 1\). To find the metric function f(r), we should solve Eq. (6). Using this metric ansatz, the r, r component of the field equations of motion reduces to

where a prime denotes a derivative with respect to r, \(n\equiv D-2,\) \(\tilde{\alpha }_{2}\equiv (n-1)(n-2)\alpha _{2}\), and \(\tilde{\alpha }_{3}\equiv (n-1)(n-2)(n-3)(n-4)\alpha _{3}\). In general, Eq. (17) has one real and two complex solutions. But it can also have three real solutions, under appropriate conditions. We are seeking static, spherically symmetric real solutions, which restrict the density \(\rho \) and the bivector \(\Sigma _{\mu \nu }\) to being a function of r only. Further, the only possible non-zero component of a bivector \(\Sigma \) is \(\Sigma ^{tr} = - \Sigma ^{rt}\). Thus \(T^t_t=T^r_r=-\rho \Sigma ^{tr}\), and we obtain \(\partial _{r} (\sqrt{r^n T^t_t}) = 0\), which implies

for some real constant a. Clearly third-order Lovelock gravity is non-trivial only for spacetime dimensions \(D \ge 7\). Henceforth, to extract information from our analysis, we shall confine ourselves to \(D=7\), in which Eq. (17) can be easily integrated, and the solution reads

where

and

with

Here we shall impose the condition \(\tilde{\alpha } _{2}^2=3\tilde{\alpha } _{3}\;(\equiv \alpha ^2)\), which simplifies f(r) significantly, with all coefficients intact, and hence it is worthwhile to consider this case. This condition reduces f(r) to the following form:

where g(r) is given, with the notation \(\omega \equiv \frac{2}{5}C_1\), by

Note that the square root here should be defined including the sign of \(-\alpha g(r)\), i.e., \(\sqrt{[-\alpha g(r)]^2}=-\alpha g(r)\). One can confirm it by noticing that the solution has been obtained from solving a cubic equation, [11]. Equation (17) can be rewritten as

where \(F\equiv [1-f(r)]/r^2\). For \(n=5\) and \(\tilde{\alpha }^2_2=3\tilde{\alpha }_3=\alpha ^2\) this reduces, with the integration constant \(\omega \), to

Thus f(r) reads

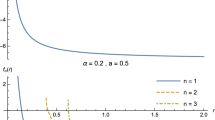

We consider only positive mass, i.e., \(\omega \ge 0\). f(r) asymptotically behaves as \(\lim \nolimits _{r\rightarrow \infty }f(r)=1\) as shown in Fig. 1 with various parameter values.

In fact, for \(D > 4\) Einstein gravity can be thought of as a particular case of Lovelock gravity, since the Einstein–Hilbert term is one of several terms that constitute the Lovelock action. Hence, for \(D > 4\) and \(\alpha = 0 \), the higher dimensional Schwarzschild solution in a string cloud model reads [32]

which goes over into Eq. (29) for \(D=7\). Equation (27), in the limit \(\alpha \rightarrow 0\), again leads to

which can also be obtained from Eq. (28) when \(D=7\). With \(a=0\), f(r) in Eq. (27) can be identified with the one in Ref. [26] with \(\beta =0\), i.e. the vanishing Born–Infeld field. The solution can be exactly verified through Ref. [14]. Since \(\omega \) represents the mass it should be positive, \(\omega \ge 0\).

Due to the fractional power on g(r), \(f(r)=1+\frac{r^2}{\alpha }-\frac{g^{1/3}}{\alpha }\) leads to a curvature singularity at \(r=r_*\), where \(g(r_*)=0\) as in the Gauss–Bonnet case [13]. Using the expression of the Ricci scalar \(R=-[(n^2+2)F+(n+4)rF^\prime /2+r^2F^{\prime \prime }]\) from [11], one sees \(\lim \nolimits _{r\rightarrow r_*}R=\infty \). The horizon radius \(r_h\) is defined by \(f(r_h)=0\).

To see how \(r_h\) and \(r_*\) can be related, it is convenient to define \(D(r)\equiv (r^2+\alpha )^3-g(r)=3\alpha (r^4_h+\alpha r^2_h+\frac{2}{5}ar_h-\omega +\frac{1}{3}\alpha ^2)\), where \(g(r)=r^6-\frac{6}{5}a\alpha r+3\omega \alpha \). Note that \(0=D(r_h)=(r_h^2+\alpha )^3-g(r_h)\) and \(D(r_*)=(r_*^2+\alpha )^3\). Let us first consider the case with \(\alpha >0\) and \(a>0\). It is worthwhile to notice that \(g(r_h)>0\) and \(\frac{\partial D}{\partial r}=6\alpha (2r^3+\alpha r+\frac{1}{5}a)>0\). The latter tells us that only one horizon can exist. A necessary and sufficient condition for the existence of one and only one horizon can be found to be a negative y-intercept, i.e., \(\frac{1}{3}\alpha ^2-\omega \le 0\). g has a minimum at \(r=(a\alpha /5)^{1/5}\). In the case that g has a negative minimum, hence giving two singularities, \((r_{*s}, r_{*b})\), a horizon can remain in either \(0<r_h< r_{*s}\) or \(r_{*b}<r_h\) due to \(g(r_h)>0\), but the case \(r_{*b}<r_h\) leads to \(D(r_{*b})<0\), which is not true. This means that a horizon can exist only in \(0<r_h< r_{*s}\), not being covered by a horizon.

For the case \(\alpha >0\) and \(a<0\), D(r) has one minimum, which can lead to two horizons if \(\frac{1}{3}\alpha ^2-\omega \ge 0\). For \(a\le 0\) g is a monotonously increasing function with a positive y-intercept and hence there is no singularity.

When \(a=0\) there exists one horizon if \(\frac{1}{3}\alpha ^2-\omega \le 0\) and there is no singularity.

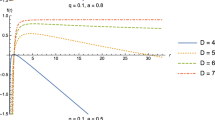

In short for \(\alpha >0\), \(\frac{1}{3}\alpha ^2-\omega <0\) is a necessary and sufficient condition for the existence of one and only one horizon for all a. Non-negative a allows only one horizon to occur, while negative a has two horizons at most (Fig. 2); then the necessary condition is \(\frac{1}{3}\alpha ^2-\omega \ge 0\). Positive a gives a naked singularity, while \(a<0\) does not give a singularity. Without a string cloud \((a=0)\) there is no singularity.

Next, consider the case \(\alpha <0\). There is one and only one singularity in this case. It is useful to notice that a horizon cannot exist between \(r_0(\equiv |\alpha |^{1/2})\) and \(r_*\). This can be checked by \(D(r)>0\) for \(r_0<r<r_*\) and \(D(r)<0\) for \(r_*<r<r_0\). We are particularly interested in whether singularities are covered by horizons. Because horizons cannot remain between \(r_0\) and \(r_*\) as mentioned above, the inequality between \(r_0\) and \(r_h\) is equivalent to one between \(r_*\) and \(r_h\), i.e. the criterion for whether singularities are covered by horizons or not. The solutions for horizons are intercepts between the curve \(l_1=r^4+\alpha r^2\) and the straight line \(l_2=-\frac{2}{5}ar+\omega -\frac{1}{3}\alpha ^2\) (Fig. 3).

For \(a>0\), \(\frac{\partial D}{\partial r}\) can have at most two zeros, leading up to maximally three horizons. If a singularity is covered by a horizon, the horizon exists in \(r>r_0\) and is the only one.

For \(a<0\) \(\frac{\partial D}{\partial r}\) has one and only one zero, leading to maximally two zeros in D. Let us consider the possibility to have two intercepts for \(r>r_0\). The necessary conditions are \(a<0\) and \(\omega -r_0^4/3\le 2ar_0/5\). The slopes of \(l_1\) and \(l_2\) are equal to \(-2a/5\) when they have one intercept. Thus \(-2a/5>\partial l_1/\partial r\vert _{r=r_0}\), i.e., \(-a\ge 5r^3_0\). However, the condition \(\omega \le 2ar_0/5+r_0^4/3\) with the first one \(-a\ge 5r^3_0\) conflicts with the positive mass condition \(\omega \ge 0\), i.e., \(\omega \le 2a r_0/5+r_0^4/3\le -2r^4_0+r^4_0/3=-5r^4_0/3\). Therefore, there can exist only one horizon in the region \(r>r_0\) and the condition for the existence of one horizon is \(\omega > r_0^4/3+2ar_0/5\). It is important to notice that this condition is just \(g(r_0)<0\). Once one horizon exists in \(r>r_0\), the other exists in \(r_{hs}<r_0\) and a singularity exists in \(r_0<r_*<r_{hb}\), i.e. the singularity stays closer to the greater horizon \(r_{hb}\).

For \(a=0\) there is a similar property to the case \(a>0\), i.e. there are at most two horizons. Only when a singularity is covered by a horizon, it is the only horizon.

The sign of \(l_2(r_0)\), equal to \(-3r_0^2g(r_0)\), tells us both whether \(r_h\) is ahead or behind from \(r_0\) and whether \(r_*\) is ahead or behind from \(r_0\). Therefore, along with the fact that there is no horizon between \(r_0\) and \(r_*\), only the configuration \(r_0\ge r_*\ge r_h\) or \(r_h\ge r_*\ge r_0\) is allowed, in other words, \(r_*\) stays closer to \(r_h\) than to \(r_0\).

In short, for \(\alpha <0\), there is only one singularity. For \(a\ge 0\) when a singularity is non-naked there should be only one horizon. For \(a<0\), when a singularity is non-naked, the singularity must be between two horizons.

In the case that a singularity is covered by a horizon, the condition \(\omega -2ar_0/5-r_0^4/3\ge 0\) must be satisfied and it gives the lower bound of the mass, unless \(\frac{2}{5}ar_0+\frac{1}{3}r^4_0<0\),

If \(\omega _{m}<0\) the lower bound for \(\omega \) must be taken to be zero.

Figure 1 shows the behaviors of the metric function f(r) with different values of parameters.

5 Thermodynamics of black holes

In this section we present the thermodynamic properties of the Lovelock black hole solution Eq. (27). As we demonstrate in the following, like any other black holes it also has thermodynamic properties. The Arnowitt–Deser-Misner (ADM) mass is defined by

where \(V_{D-2}=2\pi ^{(D-1)/2}\Gamma [(D-1)/2]\) is the area of a unit \((D-2)\) sphere. Thus the gravitational mass of the black hole is determined by \(f(r_h)=0\), which in terms of a horizon \(r_h\), from Eq. (27), reads

As \(a\rightarrow 0\), Eq. (32) becomes

which is found in [26] in the limits of the vanishing Born–Infeld electromagnetic field and cosmological constant, \((\beta ,\Lambda )\rightarrow 0\). Furthermore, in the limits \((a,\alpha )\rightarrow 0\) it leads to \(M\rightarrow \frac{5}{16}\pi ^2r^4_h\), which is the mass for the Schwarzschild black hole in seven dimensions [13]. Imposing the positive-mass condition gives either a possible range of horizon radii or mass, for fixed a and \(\alpha \). If the mass function \(M(r_h)\) has zeros, there will be critical points telling us which range of horizons is allowed. If the minimum of the mass function is positive it gives the minimum mass. Let us first think about the case \(\alpha >0\), where a singularity is not covered by a horizon. For \(\alpha >0\) and \(a\ge 0\) the minimum mass is \(\frac{5}{16} \pi ^2\frac{1}{3}\alpha ^2\). For \(\alpha >0\) and \(a<0\) the mass function can have two zeros, which means that it has zero minimum mass and there is no horizon between such two zeros. Next consider \(\alpha <0\). If one is concerned with the case that a singularity is covered by a horizon, in this case the minimum mass is \(M(r_0)\), which can be found in Eq. (30). We have

In Fig. 4 the mass function \(M(r_h)\) is plotted as a function of \(r_h\) for different values of \((a,\alpha )\).

The Hawking temperature associated with a black hole is calculated using \(T_h=\kappa /2\pi \), where \(\kappa \) is the surface gravity of a horizon. Hence, the temperature \(T_h\) at the horizon can be calculated by the definition \(T_h=f^\prime (r_h)/4\pi \), which is simplified to

From Eq. (32) the positivity of mass means \(ar_h>-\frac{5}{6}\alpha ^2-\frac{5}{2}r_h^4-\frac{5}{2}\alpha r_h^2\). This leads to the inequality, \(r_h(a+10r^3_h+5\alpha r_h)>5(\frac{3}{2}r_h^4+\frac{1}{2}\alpha r_h^2-\frac{1}{6}\alpha ^2)\). One can easily see that the right hand side in the inequality is positive for \(r_h>r_0\), i.e., \(a+10r^3_h+5\alpha r_h>0\). Thus, \(T>0\) for \(r_h>r_0\). Therefore, for \(r_h>r_0\) whenever the mass is positive, the temperature is also positive. In the limit \(a\rightarrow 0\), the temperature, Eq. (34), goes to

which is found in [26] as \((\beta ,\Lambda )\rightarrow 0\). In addition the limit \(\alpha \rightarrow 0\) further reduces it to the temperature for the Schwarzschild black hole, \(T_h\rightarrow 1/\pi r_h\). Figure 5 shows the Hawking temperature of the black holes for different values of the parameters.

For the Schwarzschild black hole in D dimensions, the entropy of the black hole, S, is given by \(S=A_h/4\) with the area of the horizon, \(A_h\), which is the \(D-2\) dimensional surface area of a sphere. However, the black hole is supposed to obey the first law of thermodynamics, \(dM = TdS\). To calculate the entropy, the integral can be performed with respect to \(r_h\),

\(\frac{\partial M}{\partial r_h}=\frac{1}{16}\pi ^2\left( 2a+20r^3_h+10\alpha r_h\right) \) leads to

Here we calculate the entropy by integration from 0 to \(r_h\). This is the usual way to define the entropy in order to make the entropy vanish when the horizon length becomes zero. Although the horizon length must be greater than \(r_0\) it should not be a concern here because the difference is only an additive constant. The integrand in S is positive, so \(S\ge 0\) in any case. Also, it is worthwhile to notice that the entropy is expressed independently of a. A similar case occurs in [26]. Actually it can be seen that this property holds in the general Lovelock theory for any static, spherically symmetric energy-momentum tensor [42]. The entropy expression in [26] coincides with Eq. (36). Using the areas of spheres \(A_{n}=2\pi ^{(n+1)/2}r^{n}/\Gamma [(n+1)/2]\) for an n dimensional surface we have \(A_{5}=\pi ^3r^5\). Only the second term, \(\frac{1}{4} \pi ^3 r_h^5\), in Eq. (36) reflects the area law \(S=A_h/4\) and the rest are usually considered as quantum corrections in higher dimensions. Figure 6 plots the behaviors of the entropy in terms of the horizon radius for different values of \(\alpha \).

The heat capacity is expressed by

Using \(\frac{\partial M}{\partial r_h}\) and \(\frac{\partial T_h}{\partial r_h}=\frac{5\alpha ^2-4 a r_h-10 r^4_h+15 \alpha r^2_h}{10\pi \left( \alpha +r^2_h\right) ^3}\), we get

In the limit \(a\rightarrow 0\), the heat capacity Eq. (38) becomes

which is found in [26] as \((\beta ,\Lambda )\rightarrow 0\). We have just seen above that from the positive mass condition, \(a+5(2r^3_h+\alpha r_h)>0\) for \(r_h>r_0\). Using the same condition, we notice that in the denominator in Eq. (38), for \(r_h>r_0\),

The right hand side is always positive when \(\alpha <0\) and \(r_h>r_0\), which makes \(C<0\), while when \(\alpha >0\), C can be either positive or negative. Therefore, the heat capacity is always negative for \(r_h>r_0\) and \(\alpha <0\) with positive mass, and hence the black hole is thermodynamically unstable in the positive mass region. However, this does not necessarily mean that the black hole is unstable as the Schwarzschild black hole is stable. The heat capacity of the black holes is plotted in Fig. 7 for various values of the parameters \((a,\alpha )\). It turns out that the parameters \((a,\alpha )\) influence the thermodynamic stability of the black holes. There exist transition points at which the sign of the heat capacity changes, i.e. there are boundaries between thermodynamically stable and unstable regions.

Let us define a transition point \(r_t\) and a critical point \(r_c\) such that C becomes zero and diverges, respectively. \(r_c\) is within the positive mass region but \(r_t\) does not always belong to it. \(r_t\) can occur at either \(A(r_t)=(\alpha +r^2_t)^3=0\) or \(B(r_t)=a+5 (2r^3_t+\alpha r_t)=0\), which makes the temperature zero. We saw that the positive mass condition guarantees that B is positive for \(r_h>r_0\). There always exists one and only one \(r_c\) for any a at \(D(r_c)=4a r_c+5 (-\alpha ^2+2r^4_c-3 \alpha r^2_c)=0\).

For \(\alpha >0\), we can see that \(A>0\) and \(r_c>r_t\) if \(r_t\) exists. Signs of C are changing like \((-, 0(r_t),+,0(r_c),-)\), from \(-\infty \) to \(\infty \).

For \(\alpha <0\) when the positive mass condition is imposed there is no zero in B for \(r_t>r_0\), which is the non-naked singularity condition, so \(r_0\) is the only zero point satisfying both the positive mass and the non-naked singularity conditions. Figure 8 shows how the heat capacity behavior changes with a after some critical values \(a_c\). For \(|a|>a_c\), \(r_c>r_t\), while for \(|a|<a_c\), \(r_c<r_t\). For \(|a|<a_c\) and \(r_c\simeq r_0\) C changes much less as a changes for \(r_h>r_0\).

6 Conclusion

Lovelock theory is a natural extension of the Einstein theory of general relativity to higher dimensions and it is a great arena for theoretical physics research. Lovelock theory describes string-inspired corrections of the Einstein–Hilbert action and hence admits general relativity as a particular case. In this paper, we have obtained exact static, spherically symmetric black hole solutions to third-order Lovelock gravity in a string cloud background in seven dimensions with the help of carefully chosen coefficients of the curvature correction terms, thereby generalizing the static, spherically symmetric black hole solutions for these theories. These solutions possess rich properties as regards the black holes and in the limits go over to the black holes in Einstein’s gravity.

The string cloud parameter a changes the number of horizons and singularities. For \(\alpha >0\), a can change the maximum number of horizons and positivity of a creates a singularity. In this case a singularity, if any, is naked. For \(\alpha <0\) there is an interesting property. A horizon cannot exist between \(r_0=|\alpha |^{1/2}\) and a singular point \(r_*\) and hence we need to know only whether a horizon is ahead or behind from \(r_0\) instead of \(r_*\) in order to see whether a singularity is naked. There is only one singularity. For \(a\ge 0\) when a singularity is non-naked there should be only one horizon. For \(a<0\), when a singularity is non-naked, the singularity must be between two horizons.

We proceeded to find exact expressions for the thermodynamic quantities like the black hole mass, the Hawking temperature, entropy, and heat capacity and in turn also analyzed the thermodynamic stability of black holes. In addition we explicitly brought to light the effect of a string cloud background on black hole solutions and their thermodynamics.

We found that a positive mass condition leads to a positive temperature for \(r_h>r_0\), which is the condition for a non-naked singularity for \(\alpha <0\). The entropy does not depend on the string cloud. This result can be extended for any spherical and static source in Lovelock theory [42]. We also see that the entropy does not obey the horizon area formula. For the heat capacity, \(\alpha >0\) the critical (singular) point \(r_c\) is greater than the transition (zero) point \(r_t\) and for \(\alpha <0\) when a positive mass and a non-naked singularity condition is applied, \(r_t=r_0\), and there is no \(r_c\). In this case the heat capacity is negative, telling us that the black hole is thermodynamically unstable like the Schwarzschild black hole.

The possibility of a further generalization of these results in arbitrarily dimensional Lovelock gravity is an interesting problem for future research.

References

S.W. Hawking, Nature 248, 30 (1974)

S. Hawking, D.N. Page, Commun. Math. Phys. 87, 577 (1983)

D. Lovelock, J. Math. Phys. 12, 498 (1971)

H.A. Buchdahl, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 150, 1 (1970)

D.J. Gross, E. Witten, Nucl. Phys. B 277, 1 (1986)

R. Emparan, H.S. Reall, Living Rev. Rel. 11, 6 (2008)

B. Zwiebach, Phys. Lett. B 156, 315 (1985)

D.G. Boulware, S. Deser, Phys. Rev. Lett. 55, 2656 (1985)

J.T. Wheeler, Nucl. Phys. B 268, 737 (1986)

R.C. Myers, J.Z. Simon, Phys. Rev. D 38, 2434 (1988)

J.T. Wheeler, Nucl. Phys. B 273, 732 (1986)

J.T. Wheeler, Nucl. Phys. B 268, 737 (1986)

R.C. Myers, J.Z. Simon, Phys. Rev. D 38, 2434 (1988)

S.H. Mazharimousavi, O. Gurtug, M. Halilsoy, Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 18, 2061 (2009)

M.H. Dehghani, N. Alinejadi, S.H. Hendi, Phys. Rev. D 77, 104025 (2008)

S.H. Hendi, M.H. Dehghani, Phys. Lett. B 666, 116 (2008)

M.M. Anber, D. Kastor, JHEP 05, 061 (2008)

R.G. Cai, L.M. Cao, Y.P. Hu, S.P. Kim, Phys. Rev. D 78, 124012 (2008)

S.H. Mazharimousavi, M. Halilsoy, Phys. Lett. B 665, 125 (2008)

C. Garraffo, G. Giribet, E. Gravanis, S. Willison, J. Math. Phys. 49, 042502 (2008)

G. Kofinas, R. Olea, JHEP 11, 069 (2007)

Q. Exirifard, M.M. Sheikh-Jabbari, Phys. Lett. B 661, 158 (2008)

R.G. Cai, Phys. Lett. B 582, 237 (2004)

R.G. Cai, Phys. Rev. D 65, 084014 (2002). arXiv:hep-th/0109133

R.G. Cai, Q. Guo, Phys. Rev. D 69, 104025 (2004). arXiv:hep-th/0311020

P. Li, R.H. Yue, D.C. Zou, Commun. Theor. Phys. 56, 845 (2011)

X.O. Camanho, J.D. Edelstein, Class. Quant. Grav. 30, 035009 (2013). arXiv:1103.3669 [hep-th]

X.O. Camanho, J.D. Edelstein, J. Maldacena, A. Zhiboedov, arXiv:1407.5597 [hep-th]

R.G. Cai, K.S. Soh, Phys. Rev. D 59, 044013 (1999)

P.S. Letelier, Phys. Rev. D 20, 1294 (1979)

E. Herscovich, M.G. Richarte, Phys. Lett. B 689, 192 (2010)

S.G. Ghosh, S.D. Maharaj, Phys. Rev. D 89, 084027 (2014)

S.G. Ghosh, U. Papnoi, S.D. Maharaj, Phys. Rev. D 90, 044068 (2014)

B. Zwiebach, Phys. Lett. B 156, 315 (1985)

B. Zumino, Phys. Rept. 137, 109 (1986)

N. Deruelle, L. Farina-Busto, Phys. Rev. D 41, 3696 (1990)

G.A. MenaMarugan, Phys. Rev. D 46, 4320 (1992)

G.A. MenaMarugan, Phys. Rev. D 46, 4340 (1992)

R.G. Cai, N. Ohta, Phys. Rev. D 74, 064001 (2006)

J.L. Synge, in relativity: the general theory, (North-Holland, Amsterdam, 1996), p. 175

M. Salgado, Class. Quant. Grav. 20, 4551 (2003). arXiv:gr-qc/0304010

T.-H. Lee, S.G. Ghosh, S. Maharaj, D. Baboolal, Thermodynamics of the Lovelock black holes in preparation

Acknowledgments

SGG thanks IUCAA for hospitality while part of the work was being done, and to SERB-DST, Government of India for Research Project Grant NO SB/S2/HEP-008/2014.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Funded by SCOAP3.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, TH., Baboolal, D. & Ghosh, S.G. Lovelock black holes in a string cloud background. Eur. Phys. J. C 75, 297 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-015-3515-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-015-3515-5