Abstract

A 28-year-old man presented with a seven-day history of testicular pain. Physical examination revealed a mass in the lower pole of the left testis. This mass was a tumour suspect on scrotal ultrasound and MRI. Testicular tumour markers were negative. A radical orchidectomy was performed. Histologically, the diagnosis of polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) was made. Retrospectively, the diagnosis of PAN could have been made earlier. The patient was treated for superficial thrombophlebitis in the months prior to admission. This was considered to be a paraneoplastic phenomenon after radical nephrectomy for a conventional type renal cell carcinoma two years earlier. After the diagnosis of PAN was made on the orchidectomy specimen, the cutaneous lesions were finally recognized as cutaneous PAN. With this knowledge, a simple testicular biopsy could have avoided a radical orchidectomy. A short review of literature on testicular PAN is given.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) is a necrotizing vasculitis of the small and medium-sized arteries. Kussmaul and Maier first described the disease in 1866 when they reported a case of necrotizing arteritis. PAN of the testis is a rare pathologic entity that at imaging can erroneously be interpreted as tumour. We report a case of testicular arteritis in a young white male.

Case report

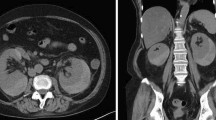

A 28-year-old white man presented with a seven-day history of left testicular pain. Prior to the present hospitalisation, the patient was treated with antibiotics by his general practitioner for presumed epididymitis. Physical examination revealed a painful mass in the lower pole of the left testis. Further investigation was unremarkable. A scrotal ultrasound confirmed a hypoechogenic mass in the lower pole of the left testis. CT scan of the abdomen and thorax showed no metastases or lymph nodes. MRI confirmed an area of heterogeneous parenchyma in the lower pole of the left testis, without invasion in the tunica albuginea. In addition, a mild hydrocoele was present (Fig. 1). Complete blood count, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, liver function tests and Hepatitis B surface antigen were normal. Testicular tumour markers were negative: beta human chorionic gonadotropin level was less than 1.0 U L−1 (normal 0.0–5.0), alpha-fetoprotein level was 6 µg L−1 (normal 0–20). C-reactive protein (CRP) was slightly elevated to 14.4 mg L−1.

Two years earlier, he had been treated for a venous thrombo-embolism of the right lower limb. Lab results at that time showed a reactive thrombocytosis. In order to rule out an underlying tumour, abdominal ultrasound and CT scan were performed. A right kidney tumour was diagnosed and a lumbar nephrectomy was performed. Pathology showed a classical-type renal cell carcinoma pT2N0, Fuhrman G II. Two years post-nephrectomy, the patient was investigated for recurrent cutaneous and subcutaneous painful nodules at the lower limbs. These lesions were thought to be superficial thrombophlebitis. Because of a history of renal cell carcinoma, it was presumed that an abnormal coagulation tendency occurred as a paraneoplastic phenomenon. However, a CT scan of the abdomen and thorax, and an onco-PET scan failed to show distant metastases or local recurrence. All coagulation tests were negative. The patient was treated empirically with low molecular weight heparin.

The patient underwent a left radical orchidectomy for the presumed testicular tumour. Pathological examination revealed the diagnosis of PAN and infarction of the testis (Fig. 2(a)–(c)).

(a) Polyarteritis nodosa. Medium-sized artery in the tunica albuginea with segmental transmural necrotizing inflammation of the vessel wall and thrombotic occlusion of the lumen. (b) Artery affected by polyarteritis nodosa at a later stage with partly destroyed wall and occlusion of the lumen by a fibroblastic proliferation and marked surrounding mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate. Note the beginning fibrinoid necrosis, as usually seen in a still later stage. (c) Detail of the fibroblastic proliferation in the lumen of an occluded artery with formation of new capillar lumina surrounded by an inflammatory infiltrate.

Discussion

Testicular pathology as a presenting symptom of vasculitis is exceptional. In most cases, testicular vasculitis occurs as a part of a systemic disease, most frequently PAN. This is an uncommon disease of unknown origin with an annual incidence of 0.7/100.000[1]. In its classical form, it affects medium and small arteries of any organ. The testis is involved in about 38–86% of all cases, but only 18% are symptomatic [2,3]. Whilst common, testicular involvement is rarely the presenting manifestation. Most often, systemic features of fever, malaise, weight loss and diffuse aching will be the first symptoms. They can present along with symptoms of multisystem involvement such as skin rash, asymmetric polyartritis and peripheral neuropathy. Laboratory tests are mostly non-specific; they reflect the systemic inflammatory nature of the disease. Thrombocytosis, elevated ESR and normochromatic anaemia are usually present[4,5].

Only a few case reports describe a painful testicular mass as the first symptom of PAN. In 1971, Mowad et al. described a 31-year-old patient presenting with a mass in the testis associated with multiple skin and subcutaneous nodules consistent with the diagnosis of PAN[6]. In 1983, Lee et al. described a 25-year-old patient who presented with bilateral testicular pain associated with paraesthesia in the distribution of the left lateral peroneal nerve and laboratory evidence of systemic PAN[7]. Diagnosis was made by testis biopsy. Shurbaji et al. described three cases of isolated necrotizing arteritis of the testis in nine autopsy cases. There was no evidence of systemic vasculitis[8]. In 1990, Huisman et al. described a 28-year-old man who presented with progressive pain and enlargement of the right testis. No clinical or laboratory findings pointed to systemic disease. Radical orchidectomy was performed[9]. In 1992, another case of isolated PAN of the testis in a 29-year-old man was described by Persellin et al. A radical orchidectomy was performed[10]. In 1993, Teichman et al. reported a 55-year-old patient with tenderness of the left testis. No mass was found. Associated systemic symptoms (spiking temperatures to 40 °C, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate up to 120 mm per hour and anaemia) were noted. Diagnosis of PAN was made through testis biopsy[11]. In 1994, Warfield et al. reported a 19-year-old patient who presented with a painful mass in the testis, suspect for tumour. A radical orchidectomy was performed. Associated, CRP was moderately elevated and the patient developed similar complaints in the contralateral testis, suggestive of systemic involvement[12]. In 1995, Mukamel et al. reported 2 cases, a 28-year-old and a 35-year-old male, presenting with discomfort and swelling of the testis. There was no evidence of systemic disease. In both patients, diagnosis of isolated PAN was made by radical orchidectomy[13]. The most recent case was presented by Eilber et al. in 2001. A 43-year-old white man presented with a testicular mass and associated systemic complaints of fever, myalgia and gross hematuria. Laboratory results revealed an elevated BUN and creatinine. ESR was 74 mm h−1. Diagnosis of PAN was made through radical orchidectomy[14].

In the presented patient, imaging studies were suspicious of testicular neoplasm. A radical orchidectomy was performed. Surprisingly, the histological diagnosis of PAN was made. Retrospectively, this diagnosis could have been suggested earlier. The patient was treated for superficial thrombophlebitis in the months prior to admission. This was thought to be a paraneoplastic phenomenon after radical nephrectomy for a conventional type renal cell carcinoma 2 years earlier. Further investigations failed to demonstrate local recurrence or metastatic disease. After the diagnosis of PAN was made on the orchidectomy specimen, the cutaneous lesions were finally recognized as cutaneous PAN. With this knowledge, a simple testicular biopsy would probably have avoided a radical orchidectomy. Testicular biopsy is a simple procedure that can be performed under local anaesthesia with minimal morbidity[7].

Early diagnosis and treatment result in an improved prognosis in PAN[15]. The prognosis of untreated systemic polyarteritis nodosa is poor and the 5-year survival is less than 13%[16]. If the disease is treated with immunosuppressive drugs (corticoids and cyclophosphamide) the 5-year survival rises from 13 to 82%[17]. The prognosis of isolated PAN of the testis seems to be more favourable. Additional treatment following orchidectomy is usually not required.

Vasculitis or PAN of the testis should be considered in the differential diagnosis when a patient presents with an acute, painful mass in the testis, without obvious trauma or epididymitis and when a tumour is suspected on ultrasound or MRI. Systemic clinical and laboratory signs are the key for the clinical diagnosis of PAN. Whenever PAN is suspected, a biopsy rather than orchidectomy must be considered.

References

Lhote F, Guillevin L. Polyarteritis nodosa, microscopic polyangiitis, and Churg-Strauss syndrome: clinical aspects and treatment. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 1995; 21: 911.

Monckeberg JG. Uber periarteritis nodosa. Beitr Path Anat 1905; 38: 101.

Patalano VJ, Sommers SC. Biopsy diagnosis of periarteritis nodosa. Arch Path 1961; 72: 1.

Diaz-Perez JL, Winkelmann RK. Cutaneous periarteritis nodosa. Arch Dermatol 1974; 110: 407–14.

Dyck PJ, Benstead TJ, Conn DL, Stevens JC, Windebank AJ, Low PA. Nonsystemic vasculitic neuropathy. Brain 1987; 110: 843–54.

Mowad JJ, Baldwin BJ, Young JD Jr. Periarteritis nodosa, presenting as mass in testis. J Urol 1971; 105: 109.

Lee LM, Moloney PJ, Wong HCG, Magil AB, McLoughlin MG. Testicular pain: an unusual representation of polyarteritis nodosa. J Urol 1983; 129: 1243–4.

Shurbaji MS, Epstein JI. Testicular vasculitis: implications for systemic disease. Hum Path 1988; 19: 186.

Huisman TK, Collins WT Jr, Voulgarakis GR. Polyarteritis nodosa masquerading as a primary testicular neoplasm: a case report and review of the literature. J Urol 1990; 144: 1236–8.

Persellin ST, Menke DM. Isolated polyarteritis nodosa of the male reproductive system. J Rheumatol 1992; 19(6): 985–8.

Teichman JMH, Mattrey RF, Demby AM, Schmidt JD. Polyarteritis nodosa presenting as acute orchitis: a case report and review of the literature. J Urol 1993; 149: 1139–40.

Warfield AT, Lee SJ, Phillips SMA, Pall AA. Isolated testicular vasculitis mimicking a testicular neoplasm. J Clin Pathol 1994; 47: 1121–3.

Mukamel E, Abarbanel J, Savion M, Konichezky M, Yachia D, Auslaender L. Testicular mass as a presenting symptom of isolated polyarteritis nodosa. Am J Clin Pathol 1995; 103(2): 215–7.

Eilber KS, Freedland SJ, Rajfer J. Polyarteritis nodosa presenting as hematuria and a testicular mass. J Urol 2001; 166: 624.

Sack M, Cassidy JT, Bole GG. Prognostic factors in polyarteritis. J Rheumatol 1975; 2: 411.

Rose GA. The natural history of polyarteritis. Br Med J 1957; 2: 1148.

Cohen RD, Conn DL, Ilstrup DM. Clinical features, prognosis, and response to treatment in polyarteritis. Mayo Clin Proc 1980; 55: 146–55.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This paper is available online at http://www.cancerimaging.org. In the event of a change in the URL address, please use the DOI provided to locate the paper.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Braeckman, P., Joniau, S., Oyen, R. et al. Polyarteritis nodosa mimicking a testis tumour: a case report and review of the literature. cancer imaging 2, 96–98 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1102/1470-7330.2002.0014

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1102/1470-7330.2002.0014