Abstract

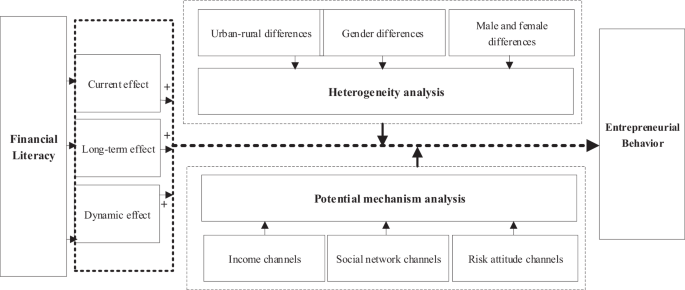

Under the backdrop of economic globalization and the digital economy, entrepreneurial behavior has emerged not only as a focal point of management research but also as an urgent topic within the domain of family finance. This paper scrutinizes the ramifications of financial literacy on household entrepreneurial behavior utilizing data from China’s sample of the China Household Finance Survey spanning the years 2015 and 2017. Employing the ordered Probit model, we pursue our research objectives. Our findings suggest that financial literacy exerts immediate, persistent, and evolving positive effects on households’ engagement in entrepreneurial activities and their proclivity toward entrepreneurship. Through the mitigation of endogeneity in the regression model, the outcomes of the two-stage regression corroborate the primary regression results. An examination of heterogeneity unveils noteworthy disparities between urban and rural areas, as well as gender discrepancies, in how financial literacy influences household entrepreneurial behavior. Furthermore, this study validates three potential pathways—namely income, social network, and risk attitude channels—demonstrating that financial literacy significantly augments household income, expands social networks, and enhances risk attitudes. Moreover, through supplementary analysis, we ascertain that financial education amplifies the impact of financial literacy on entrepreneurial behavior. Our study contributes to the enrichment of human capital theory and modern entrepreneurship theory. It advocates for robust efforts by governments and financial institutions to widely disseminate financial knowledge and foster family entrepreneurship, thereby fostering the robust and stable operation of both the global financial market and the job market.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

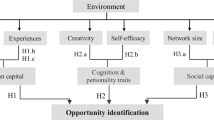

With the advancement of the global digital economy, entrepreneurship has increasingly emerged as a pivotal strategy for corporate strategic development (Cheng et al., 2024) and for the accumulation of residents’ wealth. Entrepreneurial behavior entails the optimization and integration of one’s own resources to generate substantial economic or social value. Individuals are expected to possess organizational and managerial abilities and to deliberate upon and determine the operational strategies for services, technologies, and equipment to engage in rational entrepreneurial endeavors (Levesque and Minniti, 2006). Entrepreneurial activities play a crucial role in fostering labor market prosperity, achieving social equity, enhancing the flow of social capital, and sustaining the healthy and stable functioning of the social economy (Hombert et al., 2020; Schmitz, 1989). They also hold promise for alleviating the current economic crisis through the exploitation of renewable energy sources (Abou Houran, 2023) and enhancing firm productivity (Tao et al., 2023). According to human capital theory, as posited by Becker (2009), human capital encompasses the cumulative knowledge, skills, cultural sophistication, and health status of an individual. Financial literacy, as a form of scarce human capital, constitutes a significant driver of entrepreneurial decision-making and motivation. On the one hand, the migration of individuals possessing high financial literacy fosters the transfer of theoretical knowledge and technical expertise, while the symbiotic interaction of knowledge, skills, and capabilities nurtures a reservoir of knowledge and entrepreneurial dynamism. On the other hand, individuals with elevated financial literacy are more likely to enhance their awareness and identification of opportunities within an imbalanced market, thereby bolstering their self-awareness and catalyzing independent innovation and entrepreneurship. Moreover, in line with modern entrepreneurship theory, Alvarez and Busenitz (2001) contend that entrepreneurial opportunities are endogenous. Entrepreneurs equipped with the requisite skills and knowledge pertaining to entrepreneurship are better positioned to identify and exploit opportunities. Additionally, they possess extensive and efficacious social networks, enabling them to access valuable information and resources conducive to enhancing entrepreneurial performance. Against the backdrop of economic globalization and the digital economy, governments worldwide are actively encouraging entrepreneurial engagement. They have enacted financial support policies and preferential tax measures to enhance the domestic entrepreneurial ecosystem and to galvanize individuals’ entrepreneurial potential. For instance, the Chinese government introduced numerous policies aimed at fostering entrepreneurial endeavors in 2018. Similarly, the U.S. government is proactively implementing several initiatives to foster an environment conducive to the flourishing of small and medium-sized enterprises, striving to institute permanent tax relief measures for small businesses.

However, the enhancement of the entrepreneurial environment can engender a proliferation of entrepreneurial opportunities (Segaf, 2023). Yet, the ability of entrepreneurs to seize such opportunities for proactive entrepreneurship remains constrained by numerous factors, including the development of the digital economy (Sussan and Acs, 2017; Firmansyah et al., 2023; Zhao and Weng, 2024), social networks (Karlan, 2007; Qi and Chun, 2017), human capital (Dawson et al., 2014), risk attitudes (Osman, 2014), government regulations (Black and Strahan, 2002), institutional environments (Burtch et al., 2018; Lan et al., 2018), institutional changes within universities (Eesley et al., 2016), financial constraints (Hurst and Lusardi, 2004; Asongu et al., 2020), policy interventions (Sharipov and Zaynuidinova, 2020), cognitive abilities (Haynie et al., 2012), personal beliefs regarding character and opportunity (Pidduck et al., 2023), household background, income levels, and trust (Kwon and Arenius, 2010). Entrepreneurial activities entail the identification and exploitation of entrepreneurial opportunities and the utilization of entrepreneurial resources. These endeavors invariably entail considerations of business management, financial matters, and professional concerns. Entrepreneurs must possess adequate financial literacy to ensure the rationality of entrepreneurial decision-making, the judicious allocation of entrepreneurial resources, the mitigation of venture capital risks, and the effective operation of enterprises. Drawing from a review of international experiences, scholars predominantly emphasize macroeconomic environments (Arin et al., 2015), institutional frameworks, cultural disparities (Liang et al., 2018), credit constraints (Ma et al., 2018), liquidity constraints (Beck et al., 2018), as well as micro-level factors such as social networks (Yueh, 2009), and information availability (Companys and McMullen, 2007), when examining the determinants of entrepreneurial activities.

From a current static perspective, existing studies indicate a close association between financial literacy and a range of financial behaviors and economic outcomes. A wealth of evidence demonstrates that financial literacy fosters household income growth (Behrman et al., 2012), facilitates the expansion of social networks (Kinnan and Townsend, 2012; Suresh, 2024), and enhances residents’ risk attitudes (Mishra, 2018), all of which can also impact entrepreneurial behavior. Thus, we posit that financial literacy may influence household entrepreneurial activities through three primary channels. Firstly, prior research has affirmed that higher levels of financial literacy correlate with enhanced information acquisition and processing abilities, leading to more informed decision-making (Forbes and Kara, 2010; Molina-García et al., 2023), fostering healthier and more rational investment philosophies and habits. These factors, in turn, contribute to improved investment returns and elevated household income levels. Household entrepreneurial activities necessitate sufficient financial support for use as entrepreneurial funds, and throughout the entrepreneurial process, a continuous stream of funds is required for operational and managerial purposes. Household wealth and income serve as the principal resources for family entrepreneurship, indispensable for entrepreneurial endeavors.

Secondly, studies by Korkmaz et al. (2021), Mishra (2018), and Mushafiq et al. (2023) reveal that heightened levels of financial literacy correlate with an increased likelihood of risk-taking or risk-neutrality and diminished tendencies toward risk aversion. This indicates that enhancing financial literacy significantly bolsters individuals’ risk appetites and reduces risk aversion. Entrepreneurship inherently entails risk-taking behavior and a willingness to embark on new ventures. Therefore, risk attitudes are intricately linked to entrepreneurial behavior. Research by Van Praag and Cramer (2001), as well as Long et al. (2023), spanning a 41-year study of 5800 Danish students, illustrates significant disparities in entrepreneurial willingness among individuals with varying risk preferences, with risk-conscious individuals exhibiting stronger inclinations towards entrepreneurship. Thirdly, Hong et al. (2004) and Chen et al. (2023) posit that financial literacy may proliferate through word-of-mouth or observational learning methods, thereby expanding social network structures. Social networks, as a distinct form of family capital alongside physical and human capital, facilitate risk-sharing (Munshi and Rosenzweig, 2016) and augment the likelihood of accessing formal or informal financing (Kinnan and Townsend, 2012). It is widely acknowledged that family entrepreneurial activities, to some extent, depend on the support offered by family members, relatives, and friends in terms of information, financing, and business operations and management (Munshi and Rosenzweig, 2016). Consequently, broader family social networks correlate with heightened probabilities of choosing entrepreneurship. Financial literacy can effectively mitigate information asymmetry in financial markets by enhancing family social networks, reducing monitoring costs and risky borrowing, and addressing adverse selection and moral hazard issues, thereby alleviating financing constraints and fostering family entrepreneurial activities.

The aforementioned analysis offers insights into the impact of financial literacy on household entrepreneurial activities. Nevertheless, a pivotal inquiry remains: can financial literacy effectively bolster the likelihood of family entrepreneurial choices and entrepreneurial motivation in the long term, thereby dynamically enhancing family entrepreneurial behavior? Furthermore, the urban–rural dichotomy and gender disparities in financial literacy prevalent in numerous countries may introduce variations in the current, long-term, and dynamic effects of financial literacy on residents’ entrepreneurial behavior. This prompts us to explore the existence of such disparities and whether the mechanisms underlying these differences are mediated through income, social networks, and risk attitudes. To address these gaps in the literature and elucidate the raised questions, we propose to establish a robust empirical framework. This framework will enable us to examine how financial literacy influences local households’ entrepreneurial behavior. Figure 1 illustrates our theoretical framework, delineating how financial literacy impacts household entrepreneurial activities through three primary channels.

This study empirically examines the immediate, long-term, and evolving impacts of financial literacy on household entrepreneurial activities using data from the China Household Finance Survey (CHFS) for the years 2015 and 2017. We employ the ordered Probit model to fulfill our research objectives. The findings indicate that financial literacy exerts immediate, enduring, and evolving positive effects on households’ involvement in entrepreneurial activities and their propensity toward entrepreneurship. Accounting for the endogeneity of the regression model, the results from the two-stage regression reinforce the primary regression outcomes. Heterogeneity analysis reveals significant urban–rural disparities and gender differences in the influence of financial literacy on household entrepreneurial behavior. Additionally, this research substantiates three potential pathways: income, social network, and risk attitude channels. It demonstrates that financial literacy significantly enhances household income, expands social networks, and improves risk attitudes. Further analysis reveals that financial education amplifies the impact of financial literacy on entrepreneurial behavior.

Our contributions are multifaceted: Firstly, this study advances the understanding of entrepreneurial behavior in several dimensions. Previous research primarily focuses on factors influencing entrepreneurial behavior, such as social networks (Karlan, 2007), human capital (Dawson et al., 2014), risk attitudes (Osman, 2014), government regulation (Black and Strahan, 2002), institutional environments (Lu and Tao, 2010), financial constraints (Hurst and Lusardi, 2004), cognitive ability (Haynie et al., 2012), household background, and trust (Kwon and Arenius, 2010). Few studies delve into the influence of financial literacy on entrepreneurial behaviors. We address this gap and find that financial literacy positively impacts entrepreneurial behaviors. Secondly, we measure entrepreneurial behavior at the family level, including initiative entrepreneurship in the household finance domain, thereby expanding the existing literature beyond the use of new ventures as a measurement indicator. Most importantly, our study contributes to the enrichment of human capital theory and entrepreneurship theory within the realm of household finance, providing valuable insights into the theoretical understanding of the relationship between financial literacy and entrepreneurial behavior. Thirdly, in mechanism analysis, our study is the first to investigate the three channels through which financial literacy affects household entrepreneurial behavior using CHFS data from 2015 and 2017. Lastly, our study conducts heterogeneity analysis and presents evidence of significant urban-rural disparities and gender heterogeneity in the impact of financial literacy on household entrepreneurial behavior. Furthermore, this research enhances the comprehension of the relationship between financial literacy and financial behavior. While prior studies predominantly focus on the immediate effect of financial literacy on financial behavior, our study delves deeper. We not only explore the immediate impact of financial literacy on entrepreneurial behavior but also probe into its long-term and dynamic improvement characteristics, elucidating the internal mechanisms driving these effects. For policymakers, our research provides a theoretical foundation and empirical validation to formulate entrepreneurship policies. By comprehensively understanding how financial literacy influences household entrepreneurial behavior and acknowledging the heterogeneous effects across urban–rural divides and gender disparities, governments can tailor policies to effectively support and promote entrepreneurship, thereby fostering economic growth and development. Based on the conclusions of this study, governments can fully consider residents’ financial literacy and enhance various influencing channels while encouraging innovation and entrepreneurship, thereby facilitating wealth accumulation, enhancing family welfare, and elevating the national level of innovation and entrepreneurship in entrepreneurial activities. For businesses, our research underscores the pivotal role of financial literacy in entrepreneurial activities, constituting an indispensable aspect of “entrepreneurship.” In the actual operation and management processes of enterprises, managers should prioritize the cultivation of financial literacy, as it can aid in cost reduction and the expansion of social networks, thereby realizing the healthy and stable operation of enterprises.

In the rest of this paper, the section “Literature review” reviews the relevant literature. Section “Methodology” outlines the empirical model and introduces the variables and datasets. Section “Empirical results” describes and discusses the empirical results. Section “Heterogeneity analysis” reports a heterogeneous analysis in geography, gender and income level. The section “Potential mechanism analysis” and “Further analysis: the role of financial education” discusses three channels and analyses. Section “Conclusion” concludes and policy implications.

Literature review

Factors affecting financial literacy

The financial literacy level of respondents is primarily influenced by both micro and macro environments. Concerning microelements, empirical evidence provided by Lusardi and Mitchell (2014) suggests that men tend to exhibit higher financial literacy levels than women, largely due to women’s perceived lack of self-confidence. Notably, only elderly women demonstrate high levels of self-assurance, alongside robust investment motivation and financial management interest (Bucher‐Koenen et al., 2017). Furthermore, Van Rooij et al. (2011) contend that age and financial literacy follow a hump-shaped distribution pattern, indicating that young individuals under 15 and seniors over 60 typically exhibit the lowest levels of financial literacy, while the middle-aged group tends to have the highest level. The accumulation of social experience serves to enhance the financial literacy level of the middle-aged demographic (Fong et al., 2021; Gamble et al., 2015). Moreover, Lusardi et al. (2012) found a positive correlation between the number of years of education and financial literacy, implying that higher levels of education contribute to the advancement of financial literacy.

The influence of macro-elements on financial literacy permeates various facets, shaping the financial knowledge and skills of young individuals through diverse formal and informal channels such as families, schools, communities, and workplaces (Grohmann et al., 2015). Lusardi et al. (2010) elucidated a direct correlation between the financial literacy of young individuals and the educational level and financial behavior of their parents. Moreover, Lachance (2014) uncovered that the educational level of neighbors also impacts children’s financial literacy. Danes and Haberman (2007) observed that while short-term financial literacy education and training exert some effect, direct parental education remains a more potent influencer of children’s financial literacy. Furthermore, parents’ active involvement in financial education and training programs contributes significantly to shaping children’s financial literacy. However, the literature presents mixed findings regarding the efficacy of financial education initiatives. Mandell (2008) found no enduring effects of financial education in high school on personal financial behavior, whereas Fernandes et al. (2014) suggested that financial literacy education has a limited impact, with its effectiveness waning over time. Conversely, Bruhn et al. (2013) and Lührmann et al. (2015) argued that financial education substantially enhances high school students' financial literacy. Moreover, Song (2020) conducted a field experiment in China, demonstrating that short-term financial education projects can effectively elevate financial literacy levels, thereby improving financial behavior among individuals with low financial literacy. Regarding social security mechanisms, extant literature indicates that improvements in social security significantly correlate with enhancements in residents’ financial literacy (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2011). Additionally, the social milieu plays a pivotal role, with countries experiencing high inflation rates and communities characterized by a high level of financial literacy, transparent banking policies, and frequent interactions with financially literate groups positively influencing individuals’ financial literacy levels (Lachance, 2014; Lusardi and Mitchell, 2011).

With the rapid proliferation of digital technology in the economic sphere, digitization has emerged as a ubiquitous topic of discussion among scholars (Chen and Jiang, 2024; Koskelainen et al., 2023; Jiang et al., 2024). The digitization of conventional financial industries and the entry of internet companies have catalyzed the growth of the digital finance sector (Jiang et al., 2022). Pertinent literature delves into the relationship between the advancement of digital finance and financial literacy (Prete, 2022; Yang et al., 2023). For instance, Yang et al. (2023), utilizing data from the China Household Finance Survey, found that financial literacy significantly fosters individuals’ engagement in digital finance, with this effect displaying notable heterogeneity. Drawing from cross-national data, Prete (2022) observed that the utilization of digital payment tools and platforms correlates with elevated levels of financial literacy. Koskelainen et al. (2023) endeavored to explore how varied aspects of digitization, encompassing digital financial behaviors, digital interventions, and financial technology, influence individuals’ financial literacy. Furthermore, they propose methodologies for constructing a metric of digital financial literacy.

Entrepreneurial behavior

Existing research concentrates on the determinants of entrepreneurial behavior, encompassing both macroelements and microelements. Macroelements comprise the economic environment, institutional framework, cultural disparities, credit and liquidity constraints, social networks, and information environment.

Economic development stimulates market demand for entrepreneurs and fosters entrepreneurial activities (Arin et al., 2015; AlOmari, 2024). Zhao and Weng (2024) observed that the advancement of the digital economy enhances urban innovation activities. Utilizing cross-cultural entrepreneurial cognition models, Lim et al. (2010) validated the impact of institutions on entrepreneurial activities. A nation’s formal institutions can dictate its level of economic freedom, influencing households’ entrepreneurial motivations and the types of entrepreneurial ventures pursued (McMullen et al., 2008; Kshetri, 2023). Asoni and Sanandaji (2014) demonstrated that proportional taxes do not significantly affect entrepreneurial activities, whereas progressive taxes notably boost entrepreneurship. Dong et al. (2022) revealed that local leadership turnover may serve as a barrier to entrepreneurship. Additionally, the environment for protecting private property rights is intertwined with entrepreneurial activities (Levine and Rubinstein, 2017; Hou et al., 2023). The deregulation of bank branches has intensified competition within the banking sector while greatly enhancing credit accessibility, thereby promoting household entrepreneurship (Black and Strahan, 2002). In terms of cultural disparities, Mora (2013) posited that such differences lead to variations in entrepreneurial ideas and behavioral tendencies, with entrepreneurial activities more likely to flourish in a cultural milieu characterized by low uncertainty, fostering independent thinking, valuing wealth, and eschewing conformity (Lee et al., 2020). Freytag and Thurik (2007), drawing upon data from European and American countries, concluded that culture exerts a positive and significant impact on entrepreneurial preferences but does not significantly influence actual entrepreneurial activities.

The primary challenge encountered by entrepreneurial endeavors is liquidity constraints (Banerjee and Newman, 1993; Ma et al., 2018). Banerjee and Newman (1993) contend that financial support in the form of low-interest loans, financing guarantees, and credit assurances alleviates financing constraints during entrepreneurial pursuits, thereby mitigating business risks. Information asymmetry may curtail the availability of credit services for entrepreneurs and impede household entrepreneurial activities (Stiglitz and Weiss, 1981). Wang (2012) constructed models for employment and housing decision-making, revealing that liquidity constraints influence the interaction between personal wealth and entrepreneurial decision-making. The emergence of digital finance and the Internet has mitigated information asymmetry, moral hazard, and adverse selection, safeguarding entrepreneurs’ financial security (Beck et al., 2018; Qing et al., 2024). Furthermore, it has expanded product sales channels and enhanced the accessibility of cost-effective financial services (Berger and Udell, 2002; He and Maire, 2023), thereby fostering household entrepreneurial behavior. However, Hurst and Lusardi (2004) posit that credit constraints are not the primary impediment to entrepreneurial activities, as entrepreneurs can mitigate such constraints through savings and informal credit channels.

Social networks play a pivotal role in entrepreneurial endeavors. A robust social network can furnish material capital, technical expertise, vital information, and emotional support for household entrepreneurship (Yueh, 2009; Yates et al., 2023). Social networks effectively alleviate information asymmetry, mitigate adverse selection and moral hazard (Karlan, 2007; Kerr and Mandorff, 2023), and serve as an implicit guarantee mechanism, reducing the likelihood of default on non-governmental loans (Karlan, 2007). Consequently, social networks diminish liquidity constraints, thereby promoting households’ inclination towards entrepreneurship. According to entrepreneurial vigilance theory, information asymmetry gives rise to entrepreneurial opportunities, underscoring the significance of information disparities in entrepreneurial activities (Companys and McMullen, 2007; Wang et al., 2024). Trust fosters the flow of information among different social groups, cultivating social capital, and residents with greater entrepreneurial opportunities are more inclined towards entrepreneurship (Kwon and Arenius, 2010).

Microelements encompass human capital and psychological characteristics. Regarding human capital, Berkowitz and DeJong (2005) contend that individuals with higher education levels can swiftly and accurately identify potential entrepreneurial opportunities and efficiently allocate internal and external resources. However, compared to those with average education levels, individuals with higher education face higher opportunity costs, leading to lower entrepreneurial motivation. Additionally, some studies find no significant effect of education on entrepreneurial activities (Van der Sluis et al., 2008) or observe a non-linear U-shaped relationship (Poschke, 2013). Mankiw and Weinzierl (2011) ascertain that a lack of personal ability significantly dampens households’ entrepreneurial spirit. Entrepreneurial behavior necessitates the acquisition, organization, and analysis of information, with cognitive ability reflecting an individual’s capacity to process, store, and extract information. Thus, Haynie et al. (2012) posit that cognitive ability may influence an individual’s entrepreneurial activities. Other studies explore the relationship between an individual’s age (Caliendo et al., 2014), gender (Koellinger et al., 2013), marital status, political outlook (Yueh, 2009), entrepreneurial training (Blattman et al., 2014), work experience (Lazer, 2005), type of employment (Djankov et al., 2005), health status (Rey-Martí et al., 2016), management elements (Cheng et al., 2022), education (Cui and Bell, 2022; Adeel et al., 2023; Lin et al., 2023), entrepreneurial identity (Stevenson et al., 2024), and entrepreneurial behavior.

Concerning household wealth, the majority of studies posit a positive correlation between household wealth and entrepreneurial behavior (Evans and Jovanovic, 1989). Some studies also explore the impact of accidental exogenous events and policy reforms leading to increased wealth on household entrepreneurial behavior (Blattman et al., 2014). In terms of psychological characteristics, extant literature primarily discusses the effect of risk attitude on entrepreneurial behavior. Most studies demonstrate that individual risk preference significantly influences entrepreneurial behavior, with risk-tolerant individuals exhibiting a greater propensity for entrepreneurial activities (Osman, 2014). However, Hu (2014) suggests that risk-neutral individuals are more inclined to engage in active entrepreneurial activities, whereas risk-averse and risk-tolerant individuals are more predisposed to becoming waged workers.

Existing research predominantly concentrates on the determinants of financial literacy and entrepreneurial behavior. Few studies explore the impact of financial literacy on entrepreneurial behavior. This study aims to address this gap.

Methodology

Model

Refer to prior studies (Dong et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2023; Zhao and Li, 2021; Xu et al., 2023; Graña-Alvarez et al., 2024), this study uses the \({{\rm {Probit}}}\) model to study the current and long-term effects of financial literacy on household entrepreneurial behavior. The basic regression equation is as follows:

When we study the current effect, \({{{\rm {Entrepre}}}}_{i}\) refers to entrepreneurship behavior of household \(i\) in 2015. \({{{\rm {Literacy}}}}_{i}\) represents financial literacy of household i in 2015. \({X}_{i}^{{\prime} }\) refers to control variables in 2015, including \({{\rm {gender}}}\), \({{\rm {Age}}}\), \({{{\rm {Age}}}}^{2}\), \({{\rm {Health}}}\), \({{\rm {Marriage}}}\), \({{\rm {Education}}}\), \({{\rm {RL}}}\), \({{\rm {RN}}}\), \({{\rm {RA}}}\), \({\rm {{CPC}}}\), \({{\rm {FS}}}\), \({{\rm {Assets}}}\), \({{\rm {NC}}}\), \({{\rm {NE}}}\), \({{\rm {House}}}\), and \({{\rm {NU}}}\).1 \({\mu }_{i}\) is the error term. In the above regression model, we control the province-fixed effect. The current effect is a static effect based on cross-sectional data, which mainly examines whether the current financial literacy can affect the current household entrepreneurial behavior. Most existing studies only use cross-sectional data to consider current effects.

When we study the long-term effect, \({{{\rm {Entrepre}}}}_{i}\) refers to entrepreneurship behavior of household \(i\) in 2017. \({{{\rm {Literacy}}}}_{i}\) represents the financial literacy of household \(i\) in 2015. Other designs remain unchanged. The long-term effect is mainly to test whether financial literacy can have an effect on lagging entrepreneurial behavior.

Furthermore, we use the \({{\rm {ordered}}\; {\rm {Probit}}}\) model to study the dynamic effect of financial literacy on household entrepreneurial behavior as follows:

Where \({{{\rm {Entrepre}}}}_{i}^{* }\) represents the changes in entrepreneurial behavior household \(i\) during 2015–2017, it is an ordered variable, denoted by −1, 0, and 1, respectively. \({{{\rm {Literacy}}}}_{i}\) represents financial literacy of household \(i\) in 2015. \({\varphi }_{i}\) refers to control variables in 2015. The expression of \(F\) \(\left(\cdot \right)\) function in the model (2) is as follows:

Where \({{{\rm {Entrepre}}}}_{i}^{* {\prime\prime} }\) is the latent variable of \({{{\rm {Entrepre}}}}_{i}^{* }\). \({\varepsilon }_{1} < {\varepsilon }_{2} < L < {\varepsilon }_{3}\) all are tangent points. \({{{\rm {Entrepre}}}}_{i}^{* {\prime\prime} }\) has to satisfy:

Variables

Financial literacy

Following prior studies (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2014; Zhao and Li, 2021), Table 1 reports the descriptive statistics of the answers to questions related to financial literacy as survey respondents’ financial literacy level denoted as \({{{\rm {Literacy}}}1}_{i}\). It shows that 28.67%, 16.39%, and 51.94% of the households answered the questions of interest rate calculation, inflation understanding, and venture capital correctly, respectively, indicating that most Chinese households do not understand and calculate inflation. A total of 48.17% of the households incorrectly answered the questions about interest rate calculation, implying that Chinese households lack the ability to calculate the interest rate.

Factor analysis is also often used to measure financial literacy. Following Lusardi and Mitchell (2014), we believe that the level of financial literacy represented by wrong answers and failure to answer differs. Considering this, we construct two dummy variables for each question. Therefore, we obtain six dummy variables, including dum1–dum6. The KMO test results in Table 2 show that factor analysis is reasonable. Finally, this study selects the factors with an eigenvalue greater than one as respondents’ financial literacy denoted as \({{\rm {Literacy}}}2\).

Entrepreneurial behavior

Referring to Zhao and Li (2021), the explained variable in this study is household entrepreneurial behavior, including \({{\rm {Enterpre}}}1\) and \({{\rm {Entrepre}}}2\),\(\,{{Entrepre}1}^{* }\), and\(\,{{{\rm {Entrepre}}}2}^{* }\). \({{\rm {Entrepre}}}1\) measures whether the interviewed household participates in entrepreneurial behavior and is equal to one when the household is engaged in a self-employed business operation. \({{\rm {Entrepre}}}2\) measures whether the entrepreneurial behavior of entrepreneurial families is active and is equal to 1 if the reason for the household’s participation in entrepreneurship is “want to be the boss”, “earn more”, and “want to be more flexibles and free”. \({{{\rm {Entrepre}}}1}^{* }\) represents the changes in entrepreneurial behavior of households during 2015–2017. \({{{\rm {Entrepre}}}2}^{* }\) represents the changes in initiative entrepreneurship of households during 2015–2017. Its construction method is shown in Table 3.

Data

The survey data collected by the China Household Finance Survey in 2015 and 2017 are used in this paper. This database collects a large amount of information about Chinese residents through scientific surveys and statistical methods, and it is widely used in scientific research. The CHFS has designed relevant questions about the financial literacy of the interviewees. Samples with missing values are excluded. Table 4 provides the descriptive statistics of the variables. It is worth mentioning that CHFS has been widely adopted (Zhao and Li, 2021; Yang et al., 2023).

Empirical results

Financial literacy and entrepreneurial behavior

Columns (1)–(4) in Table 5 report the estimated results of the current effect. The estimated coefficients of financial literacy in columns (1) and (2) are significant at the level of 5% and 1%, respectively, indicating that the improvement of financial literacy can significantly improve the possibility of household entrepreneurship. This result shows that financial literacy is an important determinant of household entrepreneurship decision-making, and it is the driver of household entrepreneurial activities. We found an interesting conclusion from the estimation results of the control variables. From the results in columns (1)–(4), we find that the education level of the head of the household is significantly negatively correlated with the household entrepreneurial behavior. However, the impact of our financial literacy on household entrepreneurial behavior was positive. This result seems to go against our intuition. We think that because financial literacy education is different from general education. Ordinary education mainly emphasizes the popularization and popularization of knowledge, while financial literacy education should be a kind of targeted specialized education. This conclusion supports the conclusion of the majority of the current literature.

The regression model may suffer endogenous problems. Endogeneity mainly comes from two aspects. First, a reverse causal relationship exists between financial literacy and household entrepreneurial choice. The accumulation of entrepreneurial experience may also lead to improved financial literacy. Second, the respondents may guess the answers to financial questions, leading to inaccurate measurement of financial literacy. Following Bucher-Koenen and Lusardi (2011) and Jappelli and Padula (2013), we selected the highest educational level among parents as an instrumental variable. We chose this instrumental variable for two main reasons. First, the family is the first place where individuals acquire and learn knowledge after they are born. Generally speaking, the higher the education level of parents, the more emphasis they will put on the education of their children. Parents with a high level of education can better help their children develop study habits and guide their children to receive more and better education through precepts and deeds and subtle influences in the daily life of the family. This will allow them to know more about their computing power and knowledge of economics and finance and possibly have a higher level of financial literacy. Second, the educational level of parents is determined before their children start a business and is independent of the entrepreneurial decisions of their children’s families. This suggests that parents’ educational level is strictly exogenous relative to their children’s entrepreneurial decisions. Therefore, we think it is appropriate to use parental education level as an instrumental variable. The problem that cannot be ignored is that parents with higher education levels are more likely to provide more resources for their children to start a business through their relationship network. We address this issue by controlling the parental network in our model. The results show that both the correlation test and the exogenous test of the instrumental variable of parental education level have passed, which verifies the validity of the instrumental variable to a certain extent. The results in Columns (3) and (4) in Table 5 support our conclusion.

Columns (5)–(8) in Table 5 report the estimated results of the current effect of financial literacy on household initiative entrepreneurship (\({{\rm {Entrepre}}}2\)). The results in columns (5) and (6) of Table 5 show that the estimated coefficients of financial literacy are significant at the level of 10%, indicating that financial literacy can help raise the household’s motivation for entrepreneurship in the current period and promote the initiative in entrepreneurship. Columns (7) and (8) in Table 5, The DWH test, first-stage estimated and instrumental variables show that financial literacy will help raise the household’s motivation for entrepreneurship in the current period and promote the initiative in entrepreneurship.

Table 6 reports the estimated results of the long-term effect of financial literacy on household entrepreneurial behavior. No matter what index is used to measure financial literacy, the estimated coefficient of financial literacy is statistically significantly positive, indicating that financial literacy is beneficial to increasing the probability of households participating in entrepreneurial activities and taking the initiative in entrepreneurship in the long term.

Table 7 reports the estimation results of the ordered \({{\rm {Probit}}}\) model to estimate the dynamic improvement effect of financial literacy on household entrepreneurial behavior. In Table 7, columns (1) and (2) show that no matter what index is used to measure financial literacy, the estimated coefficient of financial literacy is statistically significantly positive. After controlling endogenous concerns, we can obtain consistent results in columns (3) and (4). Columns (5)–(8) in Table 7, no matter what index is used to measure financial literacy, the estimated coefficient of financial literacy is statistically significantly positive. We find that the improvement of financial literacy level is helpful in promoting the development of household entrepreneurial decision-making and initiative in entrepreneurship.

The above empirical results suggest that improving financial literacy levels may significantly promote family participation in entrepreneurial activities and household initiative in entrepreneurship. This conclusion is consistent with the conclusion of Xu et al. (2023), indicating that financial literacy may have current, long-term, and dynamic effects on some financial behaviors. This effect has the characteristics of current, long-term, and dynamic improvement. This study provides a reasonable explanation for the findings that financial literacy adds to entrepreneurs’ understanding of business activities and market dynamics, enabling them to discover entrepreneurial opportunities better.

Robustness checks

We conduct the robustness checks by replacing the proxy index of financial literacy. We construct three dummy variables, namely, \({{\rm {Dum}}}1\), \({{\rm {Dum}}}3\), and \({{\rm {Dum}}}\)5. We use these three dummy variables to replace the explanatory variable \({{\rm {Entrepre}}}1\) or \({{\rm {Entrepre}}}2\) in the model (1) and model (2). \({{\rm {Dum}}}1\) means the answers the interest rate calculation question correctly, \({{\rm {Dum}}}2\) means the answers the inflation question correctly, \({{\rm {Dum}}}3\) means the answers the inflation question correctly. Table 8 reports the corresponding estimated results. The estimated coefficients of \({{\rm {Dum}}}1\) and \({{\rm {Dum}}}3\) are not significant. However, no matter what index is used to measure financial literacy, the estimated coefficient of \({{\rm {Dum}}}5\) is statistically significantly positive, indicating that venture capital literacy can significantly improve household entrepreneurial activities and motivation to initiate entrepreneurship.

In addition, we use respondents’ attention to economic and financial information to measure it denoted as \({Attention}\). We use \({attention}\) to replace the explanatory variable \({Literacy}1\) or \({Literacy}2\) in the model (1) and model (2). Table 9 results show that the estimated coefficient of \({Attention}\) is statistically significantly positive. It shows that attention to financial and economic information can significantly improve household entrepreneurial activity and motivation to initiate entrepreneurship, which also indicates that the influence of financial literacy is robust.

Heterogeneity analysis

Urban–rural differences

Significant differences exist between urban and rural areas in China’s economic environment, and household entrepreneurship behavior may show varying tendencies in different environments. Therefore, the effect of financial literacy on household entrepreneurship may have urban–rural heterogeneity. Table 10 reports the estimated results. Combining the size of the explanatory variable coefficient and the test results of inter-group coefficient difference, we find that the effect of financial literacy on households’ participation in entrepreneurial activities is more pronounced for households in urban areas. However, the effect of financial literacy on the initiative in entrepreneurship is more pronounced for households in rural areas.

Regarding the findings, this study provides a reasonable explanation. Compared with rural areas, urban areas have higher economic and financial development. Highly skilled personnel are also more abundant in urban areas, which leads to more opportunities for entrepreneurship. Therefore, the relationship between financial literacy and the possibility of households’ participating in entrepreneurial activities is stronger for households in urban areas. The level of income and financial development in rural areas is low, and the degree of financing constraints on households is severe. Compared with urban households who have already participated in entrepreneurial activities, rural households who have already participated in entrepreneurial activities are more eager to quickly realize “being your own boss,” “earning more,” and “being flexible and free” through initiative in entrepreneurship.

Gender differences

Gender differences in financial literacy are common in many countries (Hung et al., 2009). Lusardi and Mitchell (2014) found that in the United States, 38.3% of men can correctly answer three financial questions, but only 22.5% of women can. Only in their old age can women have financial investment motivation and a strong interest in household financial management (Tran et al., 2019). Table 11 reports the estimated results. Combining the size of explanatory variable coefficient and the test results of inter group coefficient difference, we find that the effect of financial literacy on household participation in entrepreneurial activities is more pronounced in the male sample and the effect of financial literacy on the household initiative in entrepreneurship is more pronounced in the female sample.

This study provides a reasonable explanation for the findings. Compared with women, men tend to be more confident in their economic decision-making abilities and have a stronger interest in family financial management, hoping to realize self-worth through entrepreneurship. Therefore, financial literacy has a stronger effect on men’s participation in entrepreneurial activities. Compared with men who have made entrepreneurial choices, women are more eager to realize personal financial freedom in entrepreneurship. Therefore, financial literacy has a stronger effect on women’s initiative in entrepreneurship.

Potential mechanism analysis

Income channels

On the one hand, the income gap or expansion of income levels has changed people’s relative status, intensified “relative exploitation” and social differentiation, and affected people’s “material craving” and jealousy, thereby helping to stimulate the enthusiasm of middle- and low-income groups to start a business (Mensah and Benedict, 2010). On the other hand, the most important thing at the beginning of entrepreneurship is the initial capital for family entrepreneurship, and the increase in family income provides initial capital for family entrepreneurship, thereby promoting family entrepreneurial activities (Evans and Jovanovic, 1989). To this end, this study explores whether financial literacy will affect household entrepreneurial activities through the channel of increasing household income and income level. This study estimates the following regression model to prove the income channel that financial literacy may increase household income and income rank:

where \({{{\rm {Income}}}}_{i}\) refers to the natural logarithm of the total household income.\(\,{{{\rm {Rank}}}}_{i}=1\) represents a high-income household. \({X1}_{i}\) and \({X2}_{i}\) represent control variables in 2015, including \({{\rm {gender}}}\), \({{\rm {Age}}}\), \({{{\rm {Age}}}}^{2}\), \({{\rm {Health}}}\), \({{\rm {Marriage}}}\), \({{\rm {Education}}}\), \({{\rm {RL}}}\), \({{\rm {RN}}}\), \({{\rm {RA}}}\), \({{\rm {CPC}}}\), \({{\rm {FS}}}\), \({{\rm {Assets}}}\), \({{\rm {NE}}}\), \({{\rm {NC}}}\), \({{\rm {House}}}\), and \({{\rm {NU}}}\). Other designs are consistent with the benchmark model (1). If \({\omega }_{1}\) and \({\omega }_{2}\) are significantly positive, then we can conclude that financial literacy may increase household income and income rank.

We use CHFS 2015 data to conduct empirical research to prove that financial literacy can increase household income and promote entrepreneurial activities. This study uses two indicators of total household income (\({{\rm {Income}}}\)) and income level (\({{\rm {Rank}}}\)) as household income variables. The total family income is a total indicator of income, and the income level is a relative indicator that reflects the relative level of family income. We divide the income level into two levels according to the total income of the sample. The top 50% of the total income level is defined as the high-income class, and the bottom 50% is defined as the low-income family. The endogenous problems found in the regression model are solved by the instrumental variable method. The estimation results are shown in Table 12. It shows that the estimated coefficients for \({{\rm {Literacy}}}1\) and \({{\rm {Literacy}}}2\) are significantly positive, which indicates that income channels are possible. The regression model may suffer endogenous problems. Following Bucher-Koenen and Lusardi (2011) and Jappelli and Padula (2013), we select the highest educational level among parents as an instrumental variable. Columns (5)–(8) in Table 12 show that the estimated coefficients of financial literacy are significantly above 1%, which indicates that income channels are possible.

Social network channels

In China, the family social network is mainly based on blood and geography. One of the important means of communication and relationship between relatives and friends is to give gifts to one another during the Spring Festival and other holidays and weddings and funerals. We use CHFS 2015 data for empirical research and select the family’s cash and non-cash expenditures (\({{\rm {Expenditure}}}\)), income (\({{\rm {Revenue}}}\)), and total income and expenditure (\({{\rm {Sum}}}\)) during the Spring Festival and other holidays and weddings and funerals as the proxy variables for the social network. The endogenous problems found in the regression model are solved using the two-stage instrumental variable method. This study strives to prove the social network channel that financial literacy promotes families’ cash and non-cash expenditures, revenue, and total revenue and expenditure during holidays such as the Spring Festival and weddings and funerals. Our model is as following:

where \({{SN}}_{i}\) is \({{Expenditure}}_{i}\), \({{revenue}}_{i}\), or \({{Sum}}_{i}\) refer to the social network. \({{Expenditure}}_{i}\) represents the total cash and non-cash expenditures of the family during holidays such as the Spring Festival and weddings and funerals. \({{Revenue}}_{i}\) represents the total cash and non-cash revenue of the family. \({{Sum}}_{i}\) represents the total cash and non-cash expenditures and revenue of the family. \({X3}_{i}\) represents control variables in 2015, including \({gender}\), \({Age}\), \({{Age}}^{2}\), \({Health}\), \({Marriage}\), \({Education}\), \({RL}\), \({RN}\), \({RA}\), \({CPC}\), \({FS}\), \({Assets}\), \({NE}\), \({NC}\), \({House}\), and \({NU}\). Other designs are consistent with model (1). If \({\psi }_{1}\) is significantly positive, then we can conclude that financial literacy may expand social network.

The estimated results are shown in Table 13. Following Bucher-Koenen and Lusardi (2011) and Jappelli and Padula (2013), we selected the highest educational level among parents as an instrumental variable. As can be seen from columns (1)–(6) in Panel A, \({Literacy}1\) and \({Literacy}2\) are both significantly positive at the 1% level. From columns (1)–(6) in Panel B, after controlling for endogenous factors, \({Literacy}1\) and \({Literacy}2\) are both statistically significantly positive at the 1% level. These results imply that social network channels are possible and reliable.

Risk attitude channels

We use CHFS 2015 data to conduct empirical research to prove that financial literacy can improve household risk attitudes and promote family entrepreneurial activities. We measure risk attitudes in multiple dimensions. First, we construct a comprehensive index of risk attitude. Risk preference (\({{\rm {RL}}}\)), risk neutrality (\({{\rm {RN}}}\)), and risk aversion (\({{\rm {RA}}}\)) are assigned values of 3, 2, and 1, respectively, to examine the effect of financial literacy on risk attitudes. Then, we divide risk attitudes into risk preference (\({{\rm {RL}}}\)), risk aversion (\({{\rm {RA}}}\)), and risk neutrality (\({{\rm {RN}}}\)) and generate dummy variables to examine the effect of financial literacy on these three types. Similarly, considering that there may be endogenous problems in the regression model, we use the instrumental variable method to solve the problem. This study strives to prove the risk attitude channel that financial literacy promotes risk attitude:

where \({{{\rm {Risk}}\_{\rm {attitude}}}}_{i}\) is \({{{\rm {RL}}}}_{i}\), \({{{\rm {RN}}}}_{i,}\) or \({{{\rm {RA}}}}_{i}\) in model (8), and \({{{\rm {Risk}}}}_{i}\) is \({{\rm {Risk}}}\) in model (9). Risk preference (\({{\rm {RL}}}\)), risk aversion (\({{\rm {RA}}}\)), and risk neutrality (\({{\rm {RN}}}\)) are generated as dummy variables to examine the effect of financial literacy on the three types of risk attitudes. \({{{\rm {Risk}}}}_{i}\) is a comprehensive indicator of risk attitude. We assign the values of 3, 2, and 1 to respondents’ risk preference, risk neutrality, and risk aversion, respectively, and examine the effect of financial literacy on risk attitudes. \({X4}_{i}\) represents control variables in 2015, including \({{\rm {gender}}}\), \({{\rm {Age}}}\), \({{{\rm {Age}}}}^{2}\), \({{\rm {Health}}}\), \({{\rm {Marriage}}}\), \({{\rm {Education}}}\), \({{\rm {CPC}}}\), \({{\rm {FS}}}\), \({{\rm {Assets}}}\), \({{\rm {NE}}}\), \({{\rm {NC}}}\), \({{\rm {House}}}\), and \({{\rm {NU}}}\). Other designs are consistent with the benchmark model (1). If \({\omega }_{3}\) and \({\sigma }_{1}\) are significantly positive, then we can conclude that financial literacy may improve risk attitude.

The estimation results are shown in Table 14. Columns (1)–(8) in Panel A demonstrate that the marginal effect of financial literacy on risk appetite and risk neutrality is positive, while the marginal effect on risk aversion is significantly negative. This indicates that enhancing financial literacy has led to an increase in residents’ willingness to take risks and a reduction in their aversion to risk. Additionally, the positive marginal effect of financial literacy on risk attitudes further underscores its role in improving residents’ overall risk perception. Following Bucher-Koenen and Lusardi (2011) and Jappelli and Padula (2013), we selected the highest educational level among parents as an instrumental variable. The estimation results in columns (1)–(8) of Panel B indicate that after solving the endogenous problem, the estimated coefficients or marginal effect coefficients of \({{\rm {Literacy}}}1\) and \({{\rm {Literacy}}}2\) are significantly positive at the level of 5% and above. The above results confirm the rationality of the empirical evidence that financial literacy promotes family entrepreneurial behavior by improving residents’ risk attitudes.

Further analysis: the role of financial education

The aforementioned findings substantiate the significant impact of financial literacy on family entrepreneurial behavior, thereby underscoring the importance of delving deeper into strategies aimed at enhancing residents’ financial literacy within the context of family entrepreneurship. According to Lusardi and Mitchell (2011), implementing financial education programs emerges as the most effective means to bolster residents’ financial literacy. Can financial education truly serve as a catalyst for elevating residents’ financial literacy? Furthermore, can it effectively amplify the influence of financial literacy on residents’ entrepreneurial endeavors? Investigating the intricate interplay between financial literacy, financial education, and familial entrepreneurial conduct is paramount.

In initial exploration, it becomes imperative to scrutinize the correlation between financial education and the level of financial literacy. To operationalize financial education, a binary variable is constructed, wherein a value of 1 denotes participation in coursework related to economics or finance, while a value of 0 indicates otherwise. Subsequently, the variables Literacy1 or Literacy2 are introduced to replace the interpreted variable, and the variable Learn stands in place of the interpreted variable. The control variables adhere to the framework outlined in Model (1). The estimated outcomes are presented in Table 15. Regardless of the method employed to measure financial literacy, the estimated coefficient of financial education (Learn) consistently demonstrates a statistically significant positive impact at the 1% significance level, suggesting that engagement in financial education initiatives can indeed enhance residents’ financial literacy levels. Additionally, three PSM methodologies are employed to scrutinize the influence of financial education on financial literacy. The estimated results, as detailed in Table 16, consistently reveal positive and statistically significant ATT values, thereby affirming the robustness of the aforementioned findings. These robustness checks further underscore the foundational assertion, highlighting the pivotal role of financial education in enriching family financial literacy.

Moving forward, our investigation extends to assessing whether financial education can effectively augment the influence of financial literacy on family entrepreneurial behavior. To address this inquiry, we construct an interaction term, denoted as Literacy × Learn, which captures the combined impact of financial education and financial literacy. This interaction term is incorporated into the analysis. Table 17 presents the estimated results. Irrespective of the method employed to measure financial literacy, the estimated coefficient of Literacy × Learn consistently displays a statistically significant positive association. This signifies that financial education effectively amplifies the impact of financial literacy on family entrepreneurial behavior.

An intriguing discovery emerges from our analysis: the estimated marginal effect coefficient for the interaction terms of Literacy1 × Learn or Literacy2 × Learn is notably positive, surpassing the coefficient of financial literacy alone. This observation suggests a close relationship between the impact of financial literacy on entrepreneurial behavior and individuals’ exposure to financial education. Consequently, our study substantiates that financial education serves as a moderating variable in shaping the influence of financial literacy on residents’ entrepreneurial behavior, effectively augmenting its impact. In practical terms, nationwide financial education initiatives and inclusive activities led by the People’s Bank of China, in collaboration with other financial institutions, have yielded noteworthy results over time. However, the current lack of enthusiasm and initiative among residents toward learning may hinder their engagement with financial education programs. Yet, with the proliferation of financial education efforts, this apathy is expected to wane, paving the way for increased attention and participation in financial education and training endeavors.

Conclusion

Theoretical implications

Our study draws upon human capital theory and modern entrepreneurship theory to empirically analyze the present, long-term, and evolving effects of financial literacy on household entrepreneurial behaviors, utilizing data from the CHFS in 2015 and 2017. The findings reveal that financial literacy exerts immediate, persistent, and evolving positive effects on households’ engagement in entrepreneurial activities and their propensity towards entrepreneurship. Addressing the endogeneity of the regression model, the results from the two-stage regression analysis corroborate the primary regression findings. Heterogeneity analysis highlights significant disparities between urban and rural areas as well as gender differences in how financial literacy influences household entrepreneurial behavior. Moreover, this study validates three potential mechanisms: income, social network, and risk attitude channels. We observe that financial literacy significantly enhances household income, broadens social networks, and fosters improved risk attitudes. Furthermore, our analysis indicates that financial education reinforces the impact of financial literacy on entrepreneurial behavior. These research findings carry significant theoretical implications, enriching both human capital theory and modern entrepreneurship theory.

Practical implications

This research carries significant implications for policymakers and stakeholders alike. Firstly, governments should recognize the pivotal role of financial literacy and embark on comprehensive initiatives to promote it through various channels, including television programs, radio broadcasts, informational brochures, training sessions, and specialized lectures. Establishing a sustained mechanism for the dissemination of financial literacy is crucial for enhancing the financial acumen of our nation’s populace. Secondly, special emphasis should be placed on promoting financial literacy in rural areas and among women. Collaborative efforts with financial institutions can facilitate targeted and tailored financial education projects aimed at these demographics, thereby fostering inclusivity and empowerment. By addressing the disparities in financial literacy, governments can pave the way for more equitable access to financial resources and opportunities. Thirdly, governments should actively promote financial education activities, including entrepreneurship training programs. These initiatives can mitigate the inhibitory effects of low financial literacy on entrepreneurial pursuits and enhance the management capabilities of entrepreneurs. By equipping individuals with the necessary skills and knowledge, such programs contribute to the resilience and dynamism of China’s financial market and stimulate growth in the employment landscape. In conclusion, concerted efforts to promote financial literacy and education are essential for advancing economic prosperity, fostering entrepreneurship, and ensuring inclusive development. By prioritizing these initiatives, policymakers can lay the foundation for a more resilient and prosperous future for China’s economy and society.

Future research and limitations

While our study has yielded significant insights, there are several avenues that merit further exploration in future research endeavors. Firstly, the complex relationship between cultural diversity and entrepreneurial behavior warrants deeper investigation. Unfortunately, due to the lack of detailed data on cultural diversity at the market segment level, this aspect remains largely unexplored in our study. Future research could delve into this aspect to better understand how cultural factors influence entrepreneurial decisions. Secondly, our analysis is constrained by the utilization of cross-sectional data from 2015 and 2017. Access to longitudinal data covering a broader timeframe could provide more nuanced insights and facilitate stronger conclusions. Therefore, future studies could benefit from employing larger datasets and extended panel data to comprehensively analyze the dynamics of the relationship between financial literacy and entrepreneurial behavior over time. Thirdly, the simplicity of the questionnaire used in our study may limit the depth of understanding regarding residents’ entrepreneurial behavior. Future research could address this limitation by employing more sophisticated questionnaires developed through an interdisciplinary approach, incorporating insights from psychology and other relevant fields. This holistic approach may offer a more nuanced understanding of residents’ entrepreneurial behavior, thereby enhancing the validity and reliability of the findings.

Furthermore, with the advent of the digital age, integrating elements of digitization or digital technology into academic research has become imperative. In our future research endeavors, we aim to expand our focus in several key areas. Firstly, we will explore the determinants of digital entrepreneurial behavior, examining how digital technologies influence entrepreneurial decisions and strategies. Secondly, we will emphasize the importance of digital financial literacy in shaping entrepreneurial behavior, considering how individuals’ proficiency in digital financial tools and platforms impacts their entrepreneurial activities. Lastly, we will endeavor to leverage digital technology to enhance causal identification in empirical analysis, employing innovative methodologies to better understand the mechanisms underlying the relationship between financial literacy and entrepreneurial behavior in the digital era.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the Harvard Dataverse repository: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/NRZ1K1.

References

Abou Houran M (2023) Renewable rush in Syria faces economic crisis. Financ Econ Lett 2(2):1–5

Adeel S, Daniel AD, Botelho A (2023) The effect of entrepreneurship education on the determinants of entrepreneurial behaviour among higher education students: a multi-group analysis. J Innov Knowl 8(1):100324

AlOmari AM (2024) Game theory in entrepreneurship: a review of the literature. J Bus Socio-econ Dev 4(1):81–94

Alvarez SA, Busenitz LW (2001) The entrepreneurship of resource-based theory. J Manag 27(6):755–775

Arin KP, Huang VZ, Minniti M, Nandialath AM, Reich OF (2015) Revisiting the determinants of entrepreneurship: a Bayesian approach. J Manag 41(2):607–631

Asongu SA, Nnanna J, Acha-Anyi PN (2020) Finance, inequality and inclusive education in sub-Saharan Africa. Econ Anal Policy 67:162–177

Asoni A, Sanandaji T (2014) Taxation and the quality of entrepreneurship. J Econ 113(2):101–123

Banerjee AV, Newman AF (1993) Occupational choice and the process of development. J Political Econ 101(2):274–298

Beck T, Pamuk H, Ramrattan R, Uras BR (2018) Payment instruments, finance and development. J Dev Econ 133:162–186

Becker GS (2009) Human capital: a theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education. University of Chicago Press

Behrman JR, Mitchell OS, Soo CK, Bravo D (2012) How financial literacy affects household wealth accumulation. Am Econ Rev 102(3):300–304

Berger AN, Udell GF (2002) Small business credit availability and relationship lending: the importance of bank organisational structure. Econ J 112(477):F32–F53

Berkowitz D, DeJong DN (2005) Entrepreneurship and post‐socialist growth. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 67(1):25–46

Black SE, Strahan PE (2002) Entrepreneurship and bank credit availability. J Financ 57(6):2807–2833

Blattman C, Fiala N, Martinez S (2014) Generating skilled self-employment in developing countries: experimental evidence from Uganda. Q J Econ 129(2):697–752

Bruhn M, de Souza Leão L, Legovini A, Marchetti R, Zia B (2013) The impact of high school financial education: experimental evidence from Brazil. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper (6723)

Bucher-Koenen T, Lusardi A (2011) Financial literacy and retirement planning in Germany. J Pension- Econ Financ 10(4):565–584

Bucher‐Koenen T, Lusardi A, Alessie R, Van Rooij M (2017) How financially literate are women? An overview and new insights. J Consum Aff 51(2):255–283

Burtch G, Carnahan S, Greenwood BN (2018) Can you gig it? An empirical examination of the gig economy and entrepreneurial activity. Manag Sci 64(12):5497–5520

Caliendo M, Fossen F, Kritikos AS (2014) Personality characteristics and the decisions to become and stay self-employed. Small Bus Econ 42(4):787–814

Chen H, Dai Y, Guo D (2023) Financial literacy as a determinant of market participation: new evidence from China using IV-GMM. Int Rev Econ Financ 84:611–623

Chen Z, Jiang K (2024) Digitalization and corporate investment efficiency: evidence from China. J Int Financ Mark Inst Money 91:101915

Cheng S, Fan Q, Dagestani AA (2024) Opening the black box between strategic vision on digitalization and SMEs digital transformation: the mediating role of resource orchestration. Kybernetes 53(2):580–599

Cheng Y, Zhang J, Liu Y (2022) The impact of enterprise management elements on college students’ entrepreneurial behavior by complex adaptive system theory. Front Psychol 12:769481

Companys YE, McMullen JS (2007) Strategic entrepreneurs at work: the nature, discovery, and exploitation of entrepreneurial opportunities. Small Bus Econ 28(4):301–322

Cui J, Bell R (2022) Behavioural entrepreneurial mindset: how entrepreneurial education activity impacts entrepreneurial intention and behaviour. Int J Manag Educ 20(2):100639

Danes SM, Haberman H (2007) Teen financial knowledge, self-efficacy, and behavior: a gendered view. J Financ Couns Plan 18(2). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2228406

Dawson C, Henley A, Latreille P (2014) Individual motives for choosing self-employment in the UK: does region matter? Reg Stud 48(5):804–822

Djankov S, Miguel E, Qian Y, Roland G, Zhuravskaya E (2005) Who are Russia’s entrepreneurs? J Eur Econ Assoc 3(2-3):587–597

Dong Z, Wang X, Zhang T, Zhong Y (2022) The effects of local government leadership turnover on entrepreneurial behavior. China Econ Rev 71:101727

Evans DS, Jovanovic B (1989) An estimated model of entrepreneurial choice under liquidity constraints. J Political Econ 97(4):808–827

Eesley C, Li JB, Yang D (2016) Does institutional change in universities influence high-tech entrepreneurship? Evidence from China’s Project 985. Organ Sci 27(2):446–461

Firmansyah D, Wahdiniwaty R, Budiarti I (2023) Entrepreneurial performance model: a business perspective in the digital economy era. J Bisnis Manaj Dan Ekon 4(2):125–150

Fernandes D, Lynch Jr JG, Netemeyer RG (2014) Financial literacy, financial education, and downstream financial behaviors. Manag Sci 60(8):1861–1883

Fong JH, Koh BS, Mitchell OS, Rohwedder S (2021) Financial literacy and financial decision-making at older ages. Pac-Basin Financ J 65:101481

Forbes J, Kara SM (2010) Confidence mediates how investment knowledge influences investing self-efficacy. J Econ Psychol 31(3):435–443

Freytag A, Thurik R (2007) Entrepreneurship and its determinants in a cross-country setting. J Evol Econ 17(2):117–131

Gamble KJ, Boyle PA, Yu L, Bennett DA (2015) Aging and financial decision making. Manag Sci 61(11):2603–2610

Graña-Alvarez R, Lopez-Valeiras E, Gonzalez-Loureiro M, Coronado F (2024) Financial literacy in SMEs: a systematic literature review and a framework for further inquiry. J Small Bus Manag 62(1):331–380

Grohmann A, Kouwenberg R, Menkhoff L (2015) Childhood roots of financial literacy. J Econ Psychol 51:114–133

Haynie JM, Shepherd DA, Patzelt H (2012) Cognitive adaptability and an entrepreneurial task: The role of metacognitive ability and feedback. Entrep Theory Pract 36(2):237–365

He AX, Maire DL (2023) Household liquidity constraints and labor market outcomes: evidence from a Danish mortgage reform. J Financ 78(6):3251–3298

Hombert J, Schoar A, Sraer D, Thesmar D (2020) Can unemployment insurance spur entrepreneurial activity? Evidence from France. J Financ 75(3):1247–1285

Hong H, Kubik JD, Stein JC (2004) Social interaction and stock‐market participation. J Financ 59(1):137–163

Hou B, Zhang Y, Hong J, Shi X, Yang Y (2023) New knowledge and regional entrepreneurship: the role of intellectual property protection in China. Knowl Manag Res Pract 21(3):471–485

Hu F (2014) Risk attitudes and self‐employment in China. China World Econ 22(3):101–120

Hung A, Parker AM, Yoong J (2009) Defining and measuring financial literacy. RAND Working Paper Series WR-708. https://ssrn.com/abstract=1498674

Hurst E, Lusardi A (2004) Liquidity constraints, household wealth, and entrepreneurship. J Political Econ 112(2):319–347

Jappelli T, Padula M (2013) Consumption growth, the interest rate, and financial literacy. Available at SSRN 2244086

Jiang K, Chen Z, Rughoo A, Zhou M (2022) Internet finance and corporate investment: evidence from China. J Int Financ Mark Inst Money 77:101535

Jiang K, Zhou M, Chen Z (2024) Digitalization and firms’ systematic risk in China. Int J Finance Econ https://doi.org/10.1002/ijfe.2931

Karlan DS (2007) Social connections and group banking. Econ J 117(517):F52–F84

Kerr WR, Mandorff M (2023) Social networks, ethnicity, and entrepreneurship. J Hum Resour 58(1):183–220

Kinnan C, Townsend R (2012) Kinship and financial networks, formal financial access, and risk reduction. Am Econ Rev 102(3):289–293

Koellinger P, Minniti M, Schade C (2013) Gender differences in entrepreneurial propensity. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 75(2):213–234

Korkmaz AG, Yin Z, Yue P, Zhou H (2021) Does financial literacy alleviate risk attitude and risk behavior inconsistency? Int Rev Econ Financ 74:293–310

Koskelainen T, Kalmi P, Scornavacca E, Vartiainen T (2023) Financial literacy in the digital age—a research agenda. J Consum Aff 57(1):507–528

Kshetri N (2023) The nature and sources of international variation in formal institutions related to initial coin offerings: preliminary findings and a research agenda. Financ Innov 9(1):1–38

Kwon S-W, Arenius P (2010) Nations of entrepreneurs: a social capital perspective. J Bus Ventur 25(3):315–330

Lachance ME (2014) Financial literacy and neighborhood effects. J Consum Aff 48(2):251–273

Lan S, Gao X, Wang Q, Zhang Y (2018) Public policy environment and entrepreneurial activities: evidence from China. China World Econ 26(3):88–108

Lazer D (2005) Regulatory capitalism as a networked order: The international system as an informational network. Ann Am Acad Political Soc Sci 598(1):52–66

Lee K, Jeon Y, Jo C (2020) Chinese economic policy uncertainty and US households’ portfolio decisions. Pac.-Basin Financ. J. 64:101452

Levesque M, Minniti M (2006) The effect of aging on entrepreneurial behavior. J Bus Ventur 21(2):177–194

Levine R, Rubinstein Y (2017) Smart and illicit: who becomes an entrepreneur and do they earn more? Q J Econ 132(2):963–1018

Liang J, Wang H, Lazear EP (2018) Demographics and entrepreneurship. J Political Econ 126(S1):S140–S196

Lim DS, Morse EA, Mitchell RK, Seawright KK (2010) Institutional environment and entrepreneurial cognitions: a comparative business systems perspective. Entrep Theory Pract. 34(3):491–516

Lin C, Pan Y, Yu Y, Feng L, Chen Z (2023) The influence mechanism of the relationship between entrepreneurial learning and entrepreneurial intention. Front Psychol 13:1023808

Long TQ, Morgan PJ, Yoshino N (2023) Financial literacy, behavioral traits, and ePayment adoption and usage in Japan. Financ Innov. 9(1):101

Lu J, Tao Z (2010) Determinants of entrepreneurial activities in China. J Bus Ventur 25(3):261–273

Lührmann M, Serra-Garcia M, Winter J (2015) Teaching teenagers in finance: does it work? J Bank Financ 54:160–174

Lusardi A, Mitchell OS (2011) Financial literacy and retirement planning in the United States. J Pension- Econ Financ 10(4):509–525

Lusardi A, Mitchell OS (2014) The economic importance of financial literacy: theory and evidence. J Econ Lit 52(1):5–44

Lusardi A, Mitchell OS, Curto V (2010) Financial literacy among the young. J Consum Aff 44(2):358–380

Lusardi A, Mitchell OS, Curto V (2012) Financial sophistication in the older population. NBER Working Paper, w17863. https://doi.org/10.3386/w17863

Ma YK, Xu B, Xu XF (2018) Real estate confidence index based on real estate news. Emerg Mark Financ Trade 54(4):747–760

Mandell L (2008). Financial education in high school. University of Chicago Press

Mankiw NG, Weinzierl M (2011) An exploration of optimal stabilization policy. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, pp. 209–272

McMullen JS, Bagby DR, Palich LE (2008) Economic freedom and the motivation to engage in entrepreneurial action. Entrep Theory Pract. 32(5):875–895

Mensah SA, Benedict E (2010) Entrepreneurship training and poverty alleviation: empowering the poor in the Eastern Free State of South Africa. Afr J Econ Manag Stud 1(2):138–162

Mishra R (2018) Financial literacy, risk tolerance and stock market participation. Asian Econ Financ Rev 8(12):1457–1471

Molina-García A, Dieguez-Soto J, Galache-Laza MT, Campos-Valenzuela M (2023) Financial literacy in SMEs: a bibliometric analysis and a systematic literature review of an emerging research field. Rev Manag Sci 17(3):787–826

Mora C (2013) Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind intercultural cooperation and its importance for survival. J Media Res 6(1):65–66

Munshi K, Rosenzweig M (2016) Networks and misallocation: insurance, migration, and the rural-urban wage gap. Am Econ Rev 106(1):46–98

Mushafiq M, Khalid S, Sohail MK, Sehar T (2023) Exploring the relationship between investment choices, cognitive abilities risk attitudes and financial literacy. J Econ Adm Sci 39(4):1122–1136

Osman A (2014) Occupational choice under credit and information constraints. SSRN working paper. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2449251

Pidduck RJ, Clark DR, Lumpkin GT (2023) Entrepreneurial mindset: dispositional beliefs, opportunity beliefs, and entrepreneurial behavior. J Small Bus Manag 61(1):45–79

Poschke M (2013) Who becomes an entrepreneur? Labor market prospects and occupational choice. J Econ Dyn Control 37(3):693–710

Prete AL (2022) Digital and financial literacy as determinants of digital payments and personal finance. Econ Lett 213:110378

Qi L, Chun Z (2017) An analysis of the transmission mechanism from social network to individual entrepreneurial intentions. Manag Rev 29(4):59–71

Qing L, Li P, Mehmood U (2024) Uncovering the potential impacts of financial inclusion and human development on ecological sustainability in the presence of natural resources and government stability: evidence from G-20 nations. Resour Policy 88:104446

Rey-Martí A, Ribeiro-Soriano D, Palacios-Marqués D (2016) A bibliometric analysis of social entrepreneurship. J Bus Res 69(5):1651–1655

Schmitz Jr JA (1989) Imitation, entrepreneurship, and long-run growth. J Political Econ 97(3):721–739

Segaf S (2023) Exploring perceptions and elements of entrepreneurial behavior in pesantren: understanding fundamental concepts of Entrepreneurial Behavior. Al-Tanzim 7(3):962–972

Sharipov KA, Zaynuidinova UD (2020) Investment policy of automobile transport entrepreneurs. Am J Econ Bus Manag 3(1):70–76

Song CC (2020) Financial illiteracy and pension contributions: a field experiment on compound interest in China. Rev Financ Stud 33(2):916–949

Stevenson R, Guarana CL, Lee J, Conder SL, Arvate P, Bonani C (2024) Entrepreneurial identity and entrepreneurial action: a within‐person field study. Pers Psychol 77(1):197–224

Stiglitz JE, Weiss A (1981) Credit rationing in markets with imperfect information. Am Econ Rev 71(3):393–410

Suresh G (2024) Impact of financial literacy and behavioural biases on investment decision-making. FIIB Bus Rev 13(1):72–86

Sussan F, Acs ZJ (2017) The digital entrepreneurial ecosystem. Small Bus Econ 49:55–73