Abstract

Sports have traditionally had gendered connotations in society and culture, resulting in solidified gender stereotypes that influence impression evaluations. China has a special gender social culture; however, how sport–gender stereotypes (SGS) influence the gender evaluation of people in China in the Global South is still unknown. This study obtained gender-typed sports and attribute adjectives and proved the existence of SGS through a pilot study (392 college students, n1 = 207, n2 = 185) and then used two studies to explore the influence of both explicit and implicit SGS on evaluations and compared the differences between these stereotypes and general gender stereotypes. Study 1 (395 college students, n1a = 192, n1b = 203) examined the explicit level using a questionnaire experiment. The results of two experiments showed that (1) stereotype-consistent targets were more masculine or feminine in correspondence with their gender, while stereotype-inconsistent targets had higher anti-gender traits; and (2) the inclusion of stereotype-consistent sports activities led targets to be evaluated as more masculine, while stereotype-inconsistent sport activities showed gender evaluation reversal, especially for women. Study 2 (103 college students, n2a = 61, n2b = 42) measured the implicit attitudes using the Implicit Association Test. The results of two experiments showed that (1) implicit evaluations of stereotype-consistent targets were associated faster than stereotype-inconsistent targets and (2) the inclusion of gender-typed sports weakened implicit gender evaluations. In conclusion, this is the first quantitative study to explore the unique effect of SGS on individual evaluations and how they differ from general gender stereotypes in the Chinese context. These findings could provide valuable insights for research and the application of sports social science and physical education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

People frequently differentiate among genders and form notions about the typical traits and behaviors of members of each gender. The differences between males and females are, to some extent, captured in these gender stereotypes (Ellemers, 2018). This is common in the field of sports. The sport–gender stereotypes of “sports divided into masculine and feminine sports” are prevalent around the world. For example, football and basketball are commonly seen as embodying masculinity, while dance and gymnastics are feminized (Chalabaev et al., 2013; Colley et al., 2005). Similarly, in ancient China, men were required to practice archery and riding, which lasted until the Qing dynasty.

China has a special gender and sports social culture. With China’s increasing contact with the world and as a representative of the Global South, the impact of sport–gender stereotypes on impression evaluations and how stereotypes work will be the primary focus. In recent years, several studies conducted in China have begun to focus on gender stereotypes embedded in such distinctively Chinese cultural themes as food, names, and power distance (e.g., Zuo et al., 2021; Yan and Wu, 2021). While most of the Chinese researchers’ explorations of sport–gender stereotypes are based on a sociological perspective, proposing theoretical explanations for their emergence and development, quantitative studies have mostly stayed at arguing for their existence, and psychological studies of their potential effects are even rarer. Meanwhile, in the recent period, sports have become a major symbol of masculinities (Connell, 2005). It is increasingly important to clarify the relationship between sport and gender traits in the Chinese cultural context. This study will examine the existence and influence of such stereotypes by quantitatively measuring and collecting the attitudes of college students growing up in various parts of China, both at the explicit and implicit levels, and will also explore the gender connotations of sports in comparison to general gender stereotypes.

Literature review

Gender as a social structure

Gender is socially constructed. Gender is a collection of social relations and practices integrating reproductive distinctions between bodies into social processes (Connell, 2009). Social institutions, such as families, schools, and peer groups, play a key role in the formation of gender roles. They reinforce boys’ and girls’ conformity to socially normative behaviors so that most children internalize these rules and develop character traits corresponding to socially accepted “gender roles” (Carrigan et al., 1985; Pickles, 2021). Children in turn pass on this set of norms to the next generation, making gender roles increasingly stable. Gender roles narrowly view “deviations from expectations” as “failure”, which does not reflect real-life situations (Carrigan et al., 1985). Some situations contradict definitions of gender roles, such as the girl who likes to play basketball or the boy who likes to dance, where gender roles do not seem to provide us with good insights. Over time, people have been categorized from the perspective of social gender roles and established rather rigid gender stereotypes (Lemm et al., 2005).

Gender stereotypes are common social beliefs about social groups’ personality traits and behavioral characteristics (Boiché et al., 2014) that emphasize that men and women are different (Eagly and Steffen, 1984). Both explicit and implicit gender stereotypes exist (Steffens and Jelenec, 2011). Explicit is a descriptive definition meaning direct and can be measured directly, while implicit means indirect and is the effect of early experiences on behavior (Greenwald and Lai, 2020). The Implicit Association Test (IAT) is currently regarded as the most reliable measure of an individual’s implicit perceptions (Kurdi et al., 2020). Whether explicit or implicit, gender stereotypes influence people’s attitudes and behaviors (Plaza et al., 2017). Dominance theory suggests that certain cues, such as gender, have a greater influence than others on people’s perceptions of a target (Sidanius et al., 2018). Therefore, people will use gender as an important criterion when making judgments. Participants rated the teaching behavior of teachers with male names in online courses significantly higher than that of teachers with female names (MacNell et al., 2015). Implicit gender stereotypes motivate employers to hire more men (Reuben et al., 2014), even in scientific fields where women are already scarce (Régner et al., 2019). Although there are no significant differences in brain structure and cognitive performance between men and women (e.g., Eliot et al., 2021; Joel et al., 2015), gender bias caused by gender stereotypes is still prevalent globally.

Of the more than 500,000 IATs completed in 34 countries across five continents, approximately 70% associated science with men rather than women, with Chinese Taipei, Hong Kong SAR, New Zealand, and Tunisia, having the higher-than-average implicit gender stereotypes (Nosek et al., 2009). There is a clear gender pattern in the workplace in Australia, where the majority of managers are male and service workers are female; And women’s labor participation rates are significantly lower than those of men in much of South Asia, Latin America, and some Arab countries (Pickles, 2021). These individual countries are all part of the Global South. The term “Global South” refers to the regions of Latin America, Asia, Africa, and Oceania (Dados and Connell, 2012). It is one of the products of imperialism and colonialism that once dominated the globe and is opposed to the “Global North” (Connell, 2009, 2020). While it is true that perspectives from the Global North have played a creative role and maintained hegemony in understanding gender (Banerjee and Connell, 2018), there is now a particular need for an international approach to understanding gender more fully in the context of “globalization” (Connell, 2005, 2020; Pickles, 2021).

Gender stereotypes and their impact in China

China is the largest country in the Global South. Its unique gendered cultural context provides a new perspective to understand gender stereotypes from the viewpoint of the Global South. China is ranked low on the Gender Gap Index (107/146) globally and has fallen for 13 consecutive years (World Economic Forum, 2023). Influenced by Confucianism, China’s articulation of gender differences for men and women is different from those of the West, focusing more on the social attributes of men and women, such as “male superiority and female inferiority”, and “men outside the home, women inside” (Li, 2013; Yang et al., 2023). Social role theory explains this division that corresponds to gender roles by suggesting that gender stereotypes lead to a strict prescription of what males and females are supposed to be (Eagly, 1987). Impression evaluation and formation are used synonymously (Osgood et al., 1957), so gender stereotype formation is inextricably linked to impression evaluation, i.e., cognitive judgments such as the goodness and badness of a specific impression. Such cognitive process leads to perceptual evaluation biases in evaluators (Derous et al., 2015), forming emotionally predisposed impression evaluations of both genders, causing them to show considerable resistance effects to individuals who violate expectations (Eagly and Wood, 2012). People resist counterstereotypical individuals on both cognitive and behavioral levels and then make negative evaluations of them to sustain gender stereotypes (e.g., Bosak et al., 2018; Bosak et al., 2018; Eagly et al., 2020; Liu and Zuo, 2006).

People’s responses based on the limited information provided by gender stereotypes can have a substantial effect on others’ impression evaluations (Palumbo et al., 2017; Song et al., 2017). At the explicit level, men are perceived to be more competent, and women are perceived to be warmer (Zuo et al., 2021); feminized male and female faces are perceived to be more attractive, warm, and competent than masculine faces (Wen et al., 2022). Implicit gender stereotypes also show considerable gender inequalities. Yan and Wu (2021) found that subordinates perceive male leaders as more masculine, whereas there is no difference between masculine and feminine evaluations of female leaders. Only implicitly do people perceive food stereotype-inconsistent targets as warmer than stereotype-consistent targets (Zuo et al., 2021). Xu (2003) found that both males and females implicitly view males as superior to females. Evidently, gender stereotypes affect both the users and the targets of the stereotypes (Hilton and von Hippel, 1996; Ellemers, 2018).

Sport–gender stereotypes and impression evaluations

Sport is a domain where gender differences are created, institutionalized, and established in the apparatuses of regulation (Woodward, 2009). Generally, sports are viewed as a male-dominated domain (Messner, 2011). Women in patriarchal societies are controlled by men’s power, and individuals of both genders are nested into their respective gender identities, i.e., hegemonic and submissive (Ren, 2020; Rowe, 1998). This notion is exemplified in the realm of sports, i.e., sports are portrayed as powerful, implying the male-centered nature of sports (e.g., Zhuang, 2021; Solmon, 2014; Pringle, 2005) and the masculinity in the situational specificity issues (Connell, 2005); whereas women, who are expected to be tender and submissive, suffer from awkward situations and stigmatization when participating in sports (e.g., Burrow, 2018). As men and women gradually conform to their respective social norms and exhibit and even internalize behaviors that “fit” their gender, they tend to categorize sports based on imbalances of men to women participating (Matteo, 1988). Then, sports have been categorized into masculine and feminine sports. Sports that demonstrate strength and power, such as football and basketball, are seen as expressions of masculinity, while esthetic sports, such as dance, are feminized (Chalabaev et al., 2013; Colley et al., 2005).

The majority of previous research on sport–gender stereotypes has been undertaken explicitly, revealing gender inequalities in participants’ perceptions of gender-typed sports. Stereotypes affect American males more than females (Hardin and Greer, 2009), and Swedish males regard masculine sports as more masculine (Koivula, 1995). A longitudinal follow-up study by Boiché et al. (2014) found that sport–gender stereotypes are stronger in boys, whereas girls’ stereotypes increase with age.

There has also been implicit research on sport–gender stereotypes from the viewpoint of the target gender. In Switzerland, men who accept traditional masculinity to a larger extent are more hostile toward males who depart from the standards, particularly feminized men (Iacoviello et al., 2021). Plaza et al. (2017) found that sport is gendered both implicitly and explicitly, which can influence individual participation. Moreover, women tend to evaluate neutral sports less harshly than men, indicating that women are more tolerant when evaluating individuals engaged in sports.

Sport–gender stereotypes are indeed more well-studied in the Global North. China, as the largest country in the Global South, has a long and unique history of developing sport–gender stereotypes. Chinese culture describes masculinity in terms of “hardness-softness” and “Wenwu”, i.e., cultural cultivation and martial valor. The ideal Chinese masculinity is thought to have “hardness-softness” or “Wenwu”, rather than merely “hardness” or “wu” (Fang, 2008; Louie, 2002). In other words, Chinese masculinity and femininity are not dichotomous (Zhang et al., 2011). Chinese male and female college students hold similar consciousness on sports, in practice, however, males have a more positive attitude toward exercise and are much more physically active than females (Jia et al., 2006; Zhao and Liu, 2023). Then, are sports still “dichotomous” in China as a representation of masculinity, and how do sport–gender stereotypes affect the two genders differently?

Quantitative research on sport–gender stereotypes in China is limited and focuses on college students. Zhang et al. (2010) found that when the gender of the evaluated targets differed, the participants’ attributions varied, indicating that the evaluated targets’ gender interacted with the sport–gender stereotypes. Based on this, Liu (2012) found that college students tended to associate strength-based sports with male names and technical sports with female names and that males had slightly more implicit sport–gender stereotypes than females. In conclusion, few studies in China have measured sport–gender stereotypes at both explicit and implicit levels, and have not comprehensively considered the similarities and differences between the evaluators and the evaluated subjects, which need to be further explored.

The present studies

As stated above, most studies discussing gender stereotypes are centered in the Global North (e.g., Connell, 2020; Hardin and Greer, 2009; Gülgöz et al., 2018; Wallien et al., 2010), but in the Global South, especially in China, where sports are often more linked to masculinism based on political—cultural background (Wellard, 2016; Eagly et al., 2020; Zhuang, 2021; Yang et al., 2023), the topic of gender is also very much up for discussion. We can further theorize gender power relations of masculinities by studying gender in specific contexts (e.g., sports, name, etc.) and light on center questions about gender powers (Connell, 2005). This pilot study, therefore, examined the sport–gender stereotypes of college students with fixed identities and stable cultural shaping in China.

The topic of the influence of gender stereotypes on impression evaluation has attracted much attention in both sociology and psychology, but there are differences in the research methods used across disciplines. This study intended to explore the subject deeply at both implicit and explicit levels in an attempt to reveal the influence of sport–gender stereotypes on impression evaluation using a quantitative approach.

Furthermore, previous studies have mostly verified the existence of both implicit and explicit levels, i.e., the automatic activation of gender stereotypes in association with sports (Nosek et al., 2007). In addition, social role theory, the maintenance of gender stereotype model, and dominance theory treat the impact of gender as a crucial clue about social categorization, gender features, and individual assessments. This study investigated the effect of sport–gender stereotypes on impression evaluation. Previous studies have shown that sport–gender stereotypes are sufficient to influence the ratio and number of men and women who participate in sports (Dufur and Linford, 2010; Chalabaev et al., 2013). Most studies have discussed how to define or classify gender-typed sports (e.g., Hardin and Greer, 2009), and few have considered how sport–gender stereotypes influence men’s or women’s sports choices and how athletes of different genders are evaluated. Hence, when discussing sport–gender stereotypes, this study took the gender of the target and participant into consideration and measured the gender differences in impression evaluation to further elucidate gender stereotypes and provide valuable insights for future intervention studies. We make the following hypotheses.

H1: Sport–gender stereotype can impact impression evaluation at both explicit and implicit levels, with stereotype-consistent males and stereotype-inconsistent females perceived as more masculine, and vice versa.

H2: The third-order interaction among participant gender, target gender, and stereotype (in)consistency is significant. Participants of different genders have different evaluation attitudes toward the stereotyped targets.

Finally, based on the sports domain, this study examined stereotypes because sports can influence social cognition, personality traits, etc. (e.g., Nosek et al., 2007). Previous studies on gender stereotype subfields, such as careers and names (e.g., MacNell et al., 2015; Yan and Wu, 2021), have not been compared with general gender stereotypes. To more accurately portray how gender-typed sports work in impression evaluation, this study examined Hypothesis 3.

H3: Sport–gender stereotypes and general gender stereotypes have different influences on impression evaluation at both implicit and explicit levels.

Pilot study: Identification of experimental materials

The purpose of the pilot study was to examine the sport–gender stereotypes held by college students in the Chinese context. The materials needed for Studies 1 and 2, including gender-typed sports and attribute adjectives, will also be obtained.

Participants

In the gender-typed sports evaluation phase, 207 college students were recruited (118 females, Mage = 19.36 years, SD = 1.66).

In the attribute adjective evaluation phase, 185 college students were recruited (103 females, Mage = 19.18 years, SD = 1.46). All of the participants were right-handed, had normal or corrected vision, and completed an informed consent form before the experiment began.

Experimental procedure

(1) Gender-typed sports nomination: A total of 41 sports were reviewed following a search of world-class sports and related literature.

(2) Gender-typed sports evaluation: The participants were asked to rate each of the initially screened sports items on a 10-point Likert scale. The masculine names “Yu Minghui” and “Fan Kunhong” and the feminine names “Du Huimin” and “Wang Yuexuan” were selected as typical male and female names from a study by Zuo et al. (2021) on gender-oriented names. The scenario presented to participants was as follows: “Yu Minghui/Du Huimin/Fan Kunhong/Wang Yuexuan (21 years old, college student) is choosing among a wide range of sports. If you are him or her, please rate the sport on a scale of −5 to +5 according to how suitable it is for you. A negative number is unsuitable, a positive number is suitable, and the higher the absolute value is, the greater the degree of suitability. Please avoid selecting ‘0’.”

The four sports with the highest scores were taken as masculine sports, and the four sports with the lowest scores were taken as feminine sports. The four masculine sports were football (4.26 ± 0.08), basketball (3.04 ± 0.09), wrestling (2.02 ± 0.07), and running (2.01 ± 0.08); the four feminine sports were artistic gymnastics (−2.33 ± 0.09), gymnastics (−1.76 ± 0.10), ice dance (−1.15 ± 0.09), and synchronized swimming (1.13 ± 0.08).

(3) Attribute adjectives nomination: After searching the relevant literature, the researchers identified 16 masculine attribute adjectives and 17 feminine attribute adjectives.

(4) Attribute adjective evaluation: A 10-point scale format (“−5” to “+5”) was for participants to rate each gendered attribute adjective. The four highest-scoring attribute adjectives were taken as masculine, and the four lowest-scoring attribute adjectives were taken as feminine. The four masculine attribute adjectives were virile (1.74 ± 0.25), doughty (1.11 ± 0.24), brave (1.10 ± 0.23), and stouthearted (1.09 ± 0.21); the four feminine attribute adjectives were beautiful (−0.73 ± 0.29), tender (− 0.52 ± 0.26), missish (−0.31 ± 0.24), and virtuous (−0.24 ± 0.25).

Results

In nominations and the evaluations, we found that both male and female college students held sport–gender stereotypes, and they believed that men preferred masculine sports (e.g., football, basketball), and women preferred feminine sports (e.g., artistic gymnastics, synchronized swimming).

The material was combined with each of the eight attribute adjectives to form the sport–gender stereotypes questionnaire using a 7-point scale (1 = very inconsistent, 7 = very consistent), to show the influence of explicit sport–gender stereotypes on the evaluation.

Questionnaire for Study 1a formation: The typical male/female names (Yu Minghui/Du Huimin, Fan Kunhong/Wang Yuexuan) and typical masculine/feminine sports (football/basketball, artistic gymnastics/synchronized swimming) used in the pilot experiment were selected and combined to compile textual materials to form gender-stereotyped consistent target descriptions (e.g., “Yu Minghui likes playing basketball”, “Du Huimin likes playing artistic gymnastics”) and vice versa (e.g., “ Fan Kunhong likes playing artistic gymnastics”, “Wang Yuexuan likes playing basketball”). The participants were then asked to evaluate the conformity of the target descriptions with the eight attribute adjectives (e.g., “Yu Minghui likes playing basketball. Please evaluate the following eight words to match his/her personality traits based on this sentence.”). Each participant will be asked to evaluate each of the stereotype-consistent and inconsistent male and female targets, for a total of four targets. The order in which each target appeared was counterbalanced among participants.

The material was also used in the development of the gender stereotypes questionnaire for Study 1b and IATs for Study 2.

Study 1: The effect of explicit sport–gender stereotypes

Study 1a: The impact of explicit sport–gender stereotypes on impression evaluations

This study explored how explicit sport–gender stereotypes influence gender evaluations of individuals and gender differences between evaluators and evaluated targets in the evaluation process.

Method

Participants

The study used G*Power 3.1 (Faul et al., 2007) to calculate the sample size with the effect set to 0.25 and an α level of 0.05. According to the 2 × 2 × 2 mixed design standard, to obtain a statistical power of 0.95, at least 36 participants would be needed. The actual number of college students recruited was 192 (102 females, Mage = 19.00 years, SD = 0.71). The participants were all right-handed, and all completed an informed consent form before the experiment began.

Experimental design

A 2 (participant gender: male vs. female) × 2 (target gender: male vs. female) × 2 (stereotype: consistent vs. inconsistent) mixed design was used. Target gender was a within-subject variable, participant gender and stereotype were between-subject variables, and the dependent variables were the scores of the participant’s evaluation of the targets who were consistent or inconsistent with the sport–gender stereotypes of masculine and feminine traits.

Experimental materials

The sport–gender stereotypes questionnaire developed in the pilot study was used. The entire questionnaire and its instructions for use can be found in the Supplementary online (see Appendix B).

Experimental procedure

Participants were asked to fill out the sport–gender stereotypes questionnaire and were paid for the experiment after completion.

Results

Repeated-measures ANOVA was performed with a 2 (participant gender: male vs. female) × 2 (target gender: male vs. female) × 2 (stereotype: consistent vs. inconsistent) design to examine participants’ evaluation of whether the sport–gender stereotypes were consistent for both males and females in terms of masculine and feminine traits, to test H1 and H2 at the explicit level.

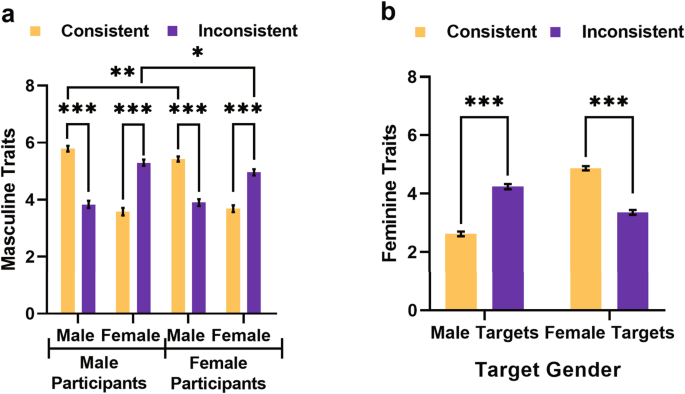

Analysis of masculine trait evaluation (see Tables 1, S1)

The main effect of target gender was significant, F(1, 190) = 28.251, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.129, the male targets (4.74 ± 0.06) were higher than the female targets (4.38 ± 0.07); the main effect of stereotype (in)consistency was significant, F(1, 190) = 5.535, p = 0.02, ηp2 = 0.028, the stereotype consistency (4.62 ± 0.06) was higher than the stereotype inconsistency (4.49 ± 0.06). The interaction between stereotype (in)consistency and target gender was significant, F(1, 190) = 398.282, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.667, and the third-order interaction among target gender, stereotype (in)consistency, and participant gender was significant, F(1, 190) = 7.062, p = 0.009, ηp2 = 0.036. Further simple effects analysis of the third-order interaction revealed (see Fig. 1a) that when participants were male, they rated stereotype-consistent male masculine traits higher (5.79 ± 0.10) than stereotype-inconsistent traits (3.83 ± 0.13), and rated stereotype-consistent female masculine traits lower (3.58 ± 0.13) than stereotype-inconsistent traits (5.29 ± 0.11); when the participants were female the results were similar to those for male participants, i.e., the evaluation of stereotype-consistent males (5.43 ± 0.09) was higher than that of stereotype-inconsistent males (3.90 ± 0.12), and the evaluation of stereotype-consistent females (3.68 ± 0.12) was lower than that of stereotype-inconsistent females (4.96 ± 0.11). Further, male participants perceived stereotype-consistent male targets (5.79 ± 0.10) and stereotype-inconsistent female targets (5.29 ± 0.11) as more masculine than female participants perceived the evaluations of stereotype-consistent male targets (5.43 ± 0.09, p = 0.008) and stereotype-inconsistent female targets (4.96 ± 0.11, p = 0.032). Results revealed that the stereotype-consistent males and stereotype-inconsistent females were perceived as more masculine, but there were also evaluator gender differences.

a Third-order interaction of participants’ evaluations of the masculine traits stereotype-(in)consistent targets. b Second-order interaction of participants’ evaluations of the feminine traits of stereotype-(in)consistent targets. Note. Error bars all indicate ±1 SE. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, or ***p < 0.001.

Analysis of feminine trait evaluation (see Tables 2, S2)

The main effect of target gender was significant, F(1, 190) = 79.287, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.294, the female targets (4.11 ± 0.06) were higher than the male targets (3.40 ± 0.07). The interaction between stereotype-(in)consistency and target gender was significant, F(1, 190) = 413.92, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.685. Further analysis of the simple effect (see Fig. 1b) showed that participants rated feminine traits higher for stereotype-inconsistent males (4.24 ± 0.09) than for stereotype-consistent males (2.62 ± 0.08), and they rated feminine traits higher for stereotype-consistent females (4.87 ± 0.07) than for stereotype-inconsistent females (3.36 ± 0.08). It revealed that the stereotype-inconsistent males and stereotype-consistent females were perceived as more feminine. None of the other interactions and main effects were significant (ps > 0.05).

Study 1b: Explicit differences between sport–gender stereotypes and general gender stereotypes

Building on Study 1a’s finding of the influence of sport–gender stereotypes, this study further explores the difference between these stereotypes and general gender stereotypes at the explicit level.

Method

Participants

For joint analysis with Experiment 1a, a minimum of 36 participants were needed. The actual number of college students recruited was 203 (95 females, Mage = 20.30 years, SD = 2.12). The college students were all right-handed, and all completed an informed consent form before the experiment began.

Experimental design

A 2 (participant gender: male vs. female) × 2 (target gender: male vs. female) × 2 (stereotype type: sport–gender stereotype test vs. general gender stereotype test) mixed design was used. Target gender was a within-subject variable, and participant gender and stereotypes were between-subject variables. The dependent variable was the difference between the masculine and feminine trait scores.

Experimental materials

The sports in the textual description of the sport–gender stereotypes questionnaire used in Study 1a were removed, leaving the typical male/female names and the attribute adjectives unchanged to obtain the general gender stereotypes questionnaire. The entire questionnaire and its instructions for use can be found in the Supplementary Online (see Appendix C).

Experimental procedure

Participants were asked to fill out the general gender stereotypes questionnaire and were paid for the experiment after completion.

Results

To more visually represent participants’ gender-evaluated attitudes toward the targets, we calculated the means of the masculine and feminine scores for both males and females in terms of general gender stereotypes and sport–gender stereotypes. We then performed paired-sample t-tests separately and found that the higher-scoring gender traits were almost always consistent with the targets’ gender (see Table 3 for details). It revealed that participants’ evaluations of each type of stereotyped target had a specific gender direction. Therefore, the scores of masculine traits minus feminine trait scores were used as the dependent variable for trait evaluation of male targets, and the scores of feminine traits minus male trait scores were used as the dependent variable for trait evaluation of female targets. The dependent variable was the indicator included in the next statistical analysis (ANOVA). However, it is worth noting that masculine traits (5.11 ± 1.08) were rated significantly higher than feminine traits (3.35 ± 1.12, p < 0.001) in female targets when sport–gender stereotypes were inconsistent.

Next, repeated-measures ANOVA was performed on 2 (stereotype type: general gender stereotype vs. sport–gender stereotype) × 2 (target gender: male vs. female) × 2 (participant gender: male vs. female) mixed design to compare the differences between the impression evaluation after adding stereotype-consistent and stereotype-inconsistent sports to the general gender stereotype impression evaluation, and to test H3 at the explicit level. Note that when the target is male, the dependent variable is masculine traits, determined by subtracting the feminine scores from the masculine scores; when the target is female, the dependent variable is feminine traits, determined by subtracting the masculine scores from the feminine scores.

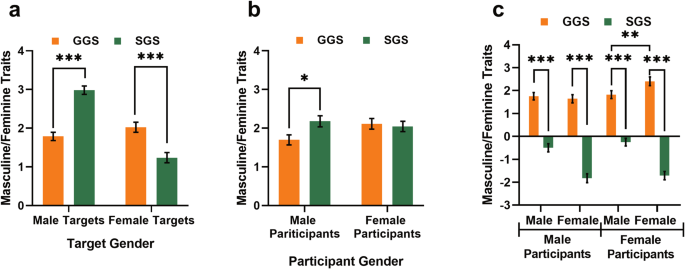

(1) When the stereotype was consistent (see Fig. 2a, b) (see Table S3), the main effect of target gender was significant, F(1, 391) = 56.800, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.127, the male targets (0.71 ± 0.09) were higher than female targets (0.13 ± 0.09); and the second-order interaction of stereotype type and target gender was significant, F(1, 391) = 98.035, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.200. Simple effects analysis revealed that masculine traits (2.98 ± 0.11) were significantly higher than general gender stereotypes (1.78 ± 0.11, p < 0.001) and feminine traits (1.24 ± 0.13) were significantly lower than general gender stereotypes (2.03 ± 0.13, p < 0.001) after the inclusion of sports activities. It revealed that the inclusion of sports activities made the targets more masculine. The second-order interaction of stereotype type and participant gender was significant, F(1, 391) = 4.071, p = 0.044, ηp2 = 0.010, and simple effects analysis revealed that only male participants perceived a significant gender trait difference between sports activity inclusion (2.18 ± 0.14) and general gender stereotypes (1.70 ± 0.13, p = 0.013). It revealed that only the male participants agreed that the inclusion of sports activities would improve the targets’ gender traits.

a Addition of the stereotype-consistent sport activities, the second-order interaction of stereotype type and target gender. b Addition of the stereotype-consistent sport activities, the second-order interaction of stereotype type and participant gender. c Adding stereotype-inconsistent sport activities, third-order interaction of target gender, stereotype type, and participant gender. Note. Error bars all indicate ±1 SE. GGS general gender stereotypes, SGS sport–gender stereotypes. *p < 0.05 or ***p < 0.001.

(2) When the stereotype was inconsistent (see Fig. 2c) (see Table S4), the main effect of target gender was significant, F(1, 391) = 30.930, p <0.001, ηp2 = 0.073, the male targets (0.71 ± 0.085) were higher than the female targets (0.13 ± 0.093); the main effect of stereotype type was significant, F(1, 391) = 424.703, p <0.001, ηp2 = 0.521, the general gender stereotype (1.91 ± 0.101) was higher than the sport–gender stereotype (−1.07 ± 0.104); the main effect of participant gender was significant, F(1, 391) = 4.198, p =0.041, ηp2 = 0.011, the female participants (0.57 ± 0.102) were higher than the male participants (1.91 ± 0.101); the interaction between target gender and stereotype type was significant, F(1, 391) = 61.412, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.136; and the third-order interaction of target gender, stereotype type, and participant gender was significant, F(1, 391) = 3.943, p = 0.048, ηp2 = 0.010. A simple effects analysis of the third-order interaction found that male participants perceived that the gender traits of males performing counterstereotypical sports (−0.50 ± 0.18) were weaker than the general gender stereotypes (1.76 ± 0.16) and that the gender traits of females performing counterstereotypical-sports (−1.83 ± 0.20) were weaker than the general gender stereotypes (1.64 ± 0.18). Female participants believed that the gender traits of males performing counterstereotypical sports (−0.26 ± 0.17) were weaker than the general gender stereotypes (1.82 ± 0.17), and the gender traits of females performing counterstereotypical sports (−1.71 ± 0.18) were weaker than the general gender stereotypes (2.41 ± 0.19). It revealed that both male and female participants agree that performing counterstereotypical sports is inappropriate for the targets’ gender traits. Additionally, female participants believed that the gender traits of general males (1.82 ± 0.17) were weaker than the general females (2.41 ± 0.19, p = 0.006), but no significant difference in male participants. This different pattern revealed that there may be a stronger self-serving tendency among females.

Study 1 focused on the explicit level. Study 1a demonstrated that explicit sport–gender stereotypes influence evaluations, as evidenced by the fact that targets who are consistent with sport-gender stereotypes have more gender-specific traits than stereotype-inconsistent targets. At the same time, both the targets and the evaluator jointly influence the evaluation process, and there are gender differences. These results validated H1 and H2 at the explicit level. In addition to discussing influence, we explored the difference between sport–gender stereotypes and general gender stereotypes through Study 1b, in which we discussed the effect of gender-typed sports on evaluations based on general gender stereotypes. Study 1b still proved that sports are considered distinctly masculine. This result partially validated H3. Meanwhile, these results were limited to the explicit level, but the implicit and explicit levels may differ; thus, Study 2 explored the effect of implicit sport–gender stereotypes.

Study 2: The effect of implicit sport–gender stereotypes

Study 2a: The impact of implicit sport–gender stereotypes on impression evaluations

This study utilized a similar design and logic as Study 1a to explore the influence of the implicit level and gender differences in the evaluation process.

Method

Participants

The study used G*Power 3.1 (Faul et al., 2007) to calculate the sample size with the effect set to 0.25 and an α level of 0.05. According to the 2 × 2 × 2 mixed design standard, to obtain a statistical power of 0.95, at least 36 participants would be needed. The actual number of college students recruited was 61 (35 females, Mage = 19.57 years, SD = 1.65). The participants were all right-handed, and all completed an informed consent form before the experiment began.

Experimental design

A 2 (participant gender: male vs. female) × 2 (target gender: male vs. female) × 2 (stereotype: consistent vs. inconsistent) mixed design was used. The participant gender was a between-subject variable, target gender and stereotype were within-group variables, and the dependent variable was reaction time to the sport activity, which was (in)consistent with the gender of the performer in the IAT.

Experimental materials

The IAT program was written in E-prime 2.0 using conceptual and attribute adjectives selected from the pilot study. We created separate IAT programs for sports-gender stereotypes with males and females as the sports performers (see Tables 4 and 5). Each IAT was administered using a 7-block criterion (Greenwald et al., 2003). The practice phase consisted of 20 trials, and the test phase consisted of 40 trials. In the sport–gender stereotypes IAT procedure, blocks 4 and 7 indicated sport and participant gender (in)consistency. Participants categorized the stereotyped pairings as well as the attribute adjectives by pressing the E or I key. We recorded and analyzed the reaction time of participants to different stereotype situations to understand their implicit evaluations.

Experimental procedure

Each participant completed two sets of the sport–gender stereotypes IAT at approximately one-week intervals, and to balance the sequence effect, participants were randomly assigned to either Task 1 (male–female targets) or Task 2 (female–male targets). Participants were informed that they needed to complete a keystroke sorting task as prompted by the instructions and to respond as quickly as possible while ensuring correctness. During the experiment, participants were asked to follow the categorization prompts at the top left and right of the screen and perform keystroke categorization of the blocks of words presented one by one in the center of the screen. Errors were identified during the practice phase and could be corrected before continuing; however, no errors were indicated during the test. A cash payment was paid for the experiment after completion.

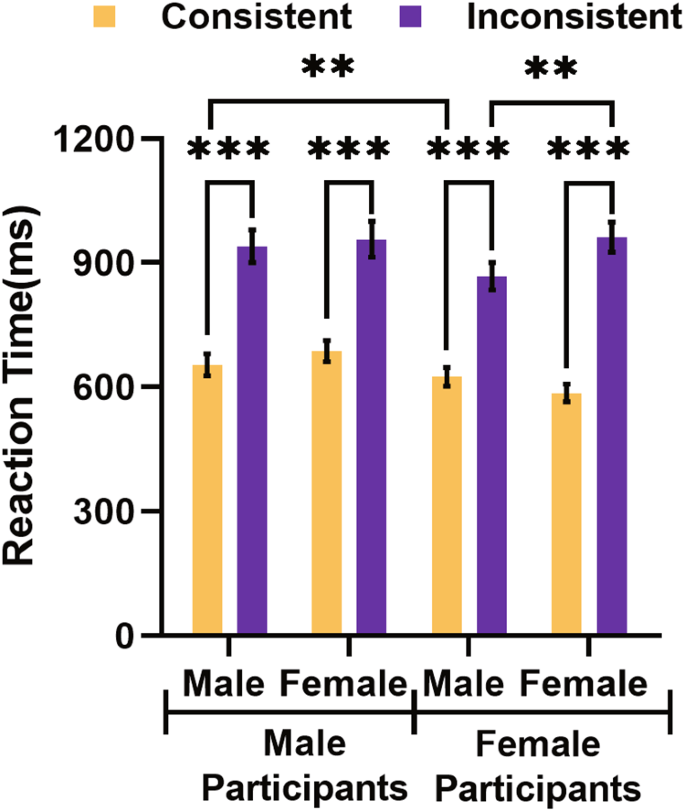

Results

Repeated-measure ANOVA on a 2 (participant gender: male vs. female) × 2 (target gender: male vs. female) × 2 (stereotype: consistent vs. inconsistent) model was conducted to examine the impact of implicit sport–gender stereotypes on impression evaluations, and test H1 and H2 at the implicit level. The results showed (see Table S5) that the third-order interaction for participant gender, target gender and stereotype (in)consistency was significant, F(1, 58) = 6.265, p = 0.015, ηp2 = 0.097; the stereotype (in)consistency main effect was significant, F (1, 58) = 258.409, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.817, the responses for consistent stereotypes (637.87 ± 14.98) were faster than inconsistent stereotypes (931.38 ± 23.48); no other main effects or interactions were significant (ps > 0.05).

Further analysis of the third-order interaction showed significant differences between both male and female participants for stereotyped congruent or incongruent objects for both males and females (see Fig. 3). Male participants differed significantly in their assessment of consistent and inconsistent male stereotypes, and their responses for consistent male stereotypes (653.64 ± 26.62) were faster than their responses for inconsistent male stereotypes (939.98 ± 39.11); male participants differed significantly for consistent and inconsistent female stereotypes, and their responses for consistent female stereotypes (687.28 ± 25.40) were faster than their responses for inconsistent female stereotypes (956.61 ± 43.39). Female participants differed significantly in their assessment of consistent and inconsistent male stereotypes, and their responses for consistent male stereotypes (624.97 ± 22.50) were faster than their responses for inconsistent male stereotypes (867.24 ± 33.06); and their assessment of consistent female stereotypes (585.57 ± 21.47) was faster than their assessment of inconsistent female stereotypes (961.69 ± 36.67). It revealed that responses to stereotype-consistent targets are commonly faster than those to stereotype-inconsistent targets. Further, male participants’ assessments of consistent male stereotypes were faster than female participants’ assessments. Further, female participants’ assessments of consistent male stereotypes (624.97 ± 22.50) were faster than male participants’ assessments (653.64 ± 26.62, p = 0.003). And female participants’ assessments of inconsistent male stereotypes (867.24 ± 33.06) were faster than inconsistent female stereotypes (961.69 ± 36.67, p = 0.008), however, there was no significant difference in male participants’ responses to these two stereotypes. It revealed that there were implicit gender differences in evaluators and targets.

Study 2b: Implicit differences between sport–gender stereotypes and general gender stereotypes

Similarly to Study 1b, this study focuses on implicit sport–gender stereotypes, exploring how they differ from general gender stereotypes and further reflecting on the similarities and differences with the explicit level.

Method

Participants

For joint analysis with Study 2a, the minimum number of participants required for Study 2b was 36, and the actual number of college students recruited was 42 (22 females, Mage = 19.25 years, SD = 1.25). The college students were all right-handed, and all completed an informed consent form before the experiment began.

Experimental design

A 2 (participant gender: male vs. female) × 2 (stereotype type: sport–gender stereotype test vs. general gender stereotype test) between-group design was used. The dependent variable was the D scores of the IAT.

Experimental materials

An IAT procedure for the evaluation of general gender-stereotyped targets (see Table 6) was created based on the IAT of Study 2a (see Tables 4 and 5), which was also administered using a 7-block criterion (Greenwald et al., 2003). The practice phase consisted of 20 trials, and the test phase consisted of 40 trials.

Experimental procedure

Each participant completed the general gender stereotypes IAT according to the same procedure as in Study 2a. A cash payment was given at the end of the experiment.

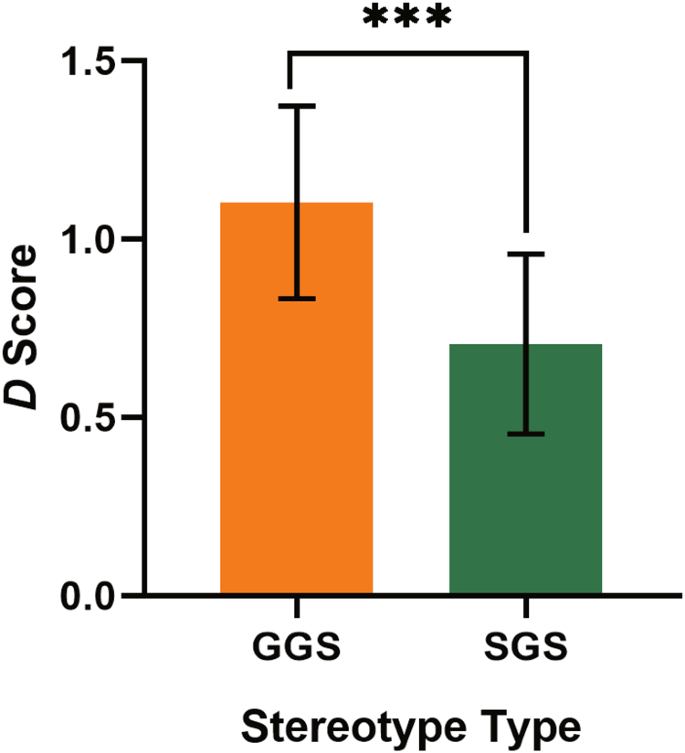

Results

Table 7 shows the subgroups’ descriptive statistics. To test H3 at the implicit level, the 2 (participant gender: male vs. female) × 2 (stereotype types: sport–gender stereotype test vs. general gender stereotype test) ANOVA results indicated a significant main effect of stereotype types, F(1, 98) = 58.032, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.372, and a higher D score for the general gender stereotype (1.10 ± 0.04) than for the sport–gender stereotype (0.70 ± 0.03) (see Fig. 4) (see Table S6). No other main effects and interactions were significant (ps > 0.05).

Study 2 focused on the implicit level, using a modified IAT to explore the impact of implicit sport–gender stereotypes on impression evaluations and how they differ from general gender stereotypes. We found that individuals implicitly associated the targets of performing gender-typed sports with their corresponding gender traits, and evaluators of different genders responded at different rates to targets of different genders. These results validated H1 and H2 at the implicit level. Additionally, by comparing the differences in IAT D scores between the two stereotypes, we suggested that sports reduced the degree of implicit association. This result further validated H3.

General discussion

This study focused on gender stereotypes and impression evaluation and investigated explicit and implicit attitudes towards males and females about sport–gender stereotypes in China in the Global South. College students were asked to rate explicitly or associate implicitly typical male and female names of individuals who played gender-consistent or inconsistent sports with masculine and feminine traits. Results indicated that sport–gender stereotypes exist, that both the gender or the target and the rater can influence the strength of these stereotypes, and that they are distinct from general gender stereotypes.

The pilot study yielded masculine and feminine sports, enabling a reexamination of the existence of sport–gender stereotypes in the Chinese context. This was also illustrated by comparing previous studies with some cross-temporal and cross-cultural consistency studies (e.g., Plaza et al., 2017; Liu, 2012; Qian et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2008). In the present study, it was hypothesized that the phenomenon of certain sports being “male” or “female” persists to this day and is expressed at both the explicit and implicit levels. Specifically, there were three main results in this study.

The effects of explicit and implicit sport–gender stereotypes on impression evaluation

Sport–gender stereotypes impact impression evaluation both explicitly and implicitly. Study 1a examined the effect at the explicit level, which was reflected in higher gender trait scores for stereotype-consistent targets, but the opposite is true for inconsistent targets. Study 2a explored the effect at the implicit level, and people were slower to react to stereotype-inconsistent targets, suggesting that inconsistency interfered with people’s normal implicit cognition, i.e., people had a cognitive conflict with counterstereotypical targets that did not conform to their inherent perceptions. Together, the two findings validated Hypothesis 1 and both verified and extended the social role theory and the maintenance of the gender stereotypes model. People tend to remember and trust stereotype-consistent information (Hilton and von Hippel, 1996); those who clearly violate stereotypes will attract our attention, and this information may further influence attributions and dominate our judgments (Ellemers, 2018; Sherman and Hamilton, 1994). When individuals violate stereotypical expectations of their corresponding gender role, people resist such counterstereotypical individuals both cognitively and behaviorally (Plaks et al., 2001). Therefore, stereotype-inconsistent individuals tend to be evaluated differently. At the same time, gender stereotypes also convey how we think people should behave (Prentice and Carranza, 2002); i.e., there is a shift from descriptive stereotypes (what is) to prescriptive stereotypes (what should be) (Roberts, 2022). In this study, stereotype-inconsistent men violated gender stereotypes about what sports they should choose as males, and therefore the evaluation of their masculinity was lowered. Again, due to the compensatory effect, whereby people lower their evaluation of one aspect while increasing the opposite aspect (Cambon and Yzerbyt, 2017), the evaluation of the feminine traits of stereotype-inconsistent men and the masculine traits of stereotype-inconsistent women increased.

The gender difference in evaluators and targets

Evaluators of different genders have different attitudes toward the targets, and individuals’ evaluations of the counterstereotypical targets of different genders are also different; therefore, Hypothesis 2 has been verified. Male participants had higher scores on the evaluation of targets of both genders than female participants did (at the explicit level); meanwhile, male and female evaluators had stronger cognitive conflicts about counterstereotypical women (at the implicit level). Women may judge other stereotypical women harshly because of the queen bee phenomenon (McKinnon and O’Connell, 2020). This differed from other studies, where previous works have found a tendency to serve the self-gender (Rudman et al., 2001; Nowicki and Lopata, 2017). In Study 2a, we found that in the stereotype-consistent case, female participants reacted faster than males when directed at female targets. When inconsistent, female participants rated male targets faster than female targets. These results may be related to the differences in sports motivation and interest between male and female college students in China, and male students have more physical activity (Jia et al., 2006; Zhao and Liu, 2023). People’s attitudes toward female athletes were significantly different from those of male athletes and tended to involve greater cognitive conflict. This finding validated the dominance theory’s view on gender salience.

Notably, female athletes are more likely to be objectified than male athletes, especially male participants (Nezlek et al., 2015). Similarly, emphasizing the gender attributes of women tended to overlook their performance and abilities (Gurung and Chrouser, 2007; Knight and Giuliano, 2001). Although these results indicate difficulties for females in sports, we call for more female participation in sports and more media coverage of outstanding female athletes from a sports perspective. Media plays a significant role in shaping attitudes towards gender roles (Haris et al., 2023). Same-sex role models are particularly valuable for women, as seen with the role model effect of mothers on girls’ interest in science (Guo et al., 2019). Because they show that success is attainable and better represents possible future selves (Midgley et al., 2021).

The difference between sport–gender stereotypes and general gender stereotypes

We discussed the differences between the two stereotypes to provide a clearer picture of the role gender-typed sports played in evaluations. The present study found differences at both the explicit and implicit levels, validating Hypothesis 3. Unexpectedly, there was also an experimental separation. Explicit and implicit measures can reflect different but interrelated processes (Hofmann et al., 2005; Nosek and Smyth, 2011). Previous research on the dual-attitude model has demonstrated that people may experience a separation between their explicit and implicit attitudes toward the same target (Breen and Karpinski, 2013). The results of Studies 1b and 2b were not identical. Study 1b found that unlike with general gender stereotypes, (1) men who performed masculine sports were considered more masculine, whereas women who performed feminine sports were considered less feminine; (2) only male participants perceived the gender traits of the evaluated targets to be more distinct; and (3) targets who were counterstereotypical were all rated as the opposite of their gender, and this effect was particularly harsh for women. In Study 2b, compared with the IAT’s D score for general gender stereotypes, that for sport–gender stereotypes is smaller, which indicates that people have a lower degree of implicit association. This suggests that sports play a buffering role in implicit social cognition. A similar study has shown that high facial attractiveness perceived without cues can weaken the negative age stereotypes of older adults (Palumbo et al., 2017).

A combined comparison of studies 1 and 2 revealed differences between the explicit and implicit levels. While implicit beliefs are not necessarily associated with the explicit endorsement of stereotypes, a certain strength of implicit perceptions can then shape behavior without the individual’s awareness (Lane et al., 2007; Nosek et al., 2002). At the same time, subjective inferences about implicit attitudes can also influence explicit attitudes, which could potentially result in prejudice and discrimination (Cooley et al., 2015). For example, compared to male patients, female patients are often belittled and are more likely to be diagnosed as being overly sensitive or hysterical (Saini, 2020).

Limitations and future research directions

This study was a preliminary exploration of the relationship between sport–gender stereotypes and evaluations of others among Chinese people, and inevitably, there were still some limitations that require future studies.

The participants and evaluated targets were Chinese college students, so the findings may not be generalizable to other groups. Furthermore, there will be variations due to, for example, generational and group factors (e.g., Jerald et al., 2017). Children begin to show identification with gender stereotypes at six (Bian et al., 2017), and this is reinforced through adolescence (Steffens et al., 2010). There is also a large body of research on athletes (e.g., Brinkschulte et al., 2020; Hermann and Vollmeyer, 2016; Hively and El-Alayli, 2014). College students were chosen because adults’ responses could be attributed to social expectations (Greenwald et al., 2002) or benevolent sexism (Glick and Fiske, 1996; Glick et al., 2000). Young people may be less inclined to hide opinions because they are in a period when gender roles and personality development are very prominent (Caspi et al., 2005). Considering most participants in previous studies were also college students, this could provide a new sample for comparison. Future research is needed to differentiate stereotypes according to different populations.

There is still much room for exploration of the implicit level, and ecological validity needs to be improved. In real life, generating evaluations is never just a simple pairing of words like in the IAT. Differences among both males and females are often greater than those between males and females, and this phenomenon is associated with stereotype formation and maintenance (Ellemers, 2018). In the future, more diverse and vivid triggers and methods can be considered, such as the use of images or videos, situational simulations, and VR. Additionally, the explanation of the intrinsic mechanisms at both the explicit and implicit levels distinguished in this study is still weak. There is also no way to further explain other meaningful effects based on only gender evaluation. Integrating various social cognitive measures (e.g., IRAP, GNAT, etc.) with cognitive neuroscience techniques (e.g., ERPs, fMRI) to explore the brain mechanisms of stereotypes can be an important direction for future research (Amodio, 2014).

Practical implications

This study can help raise awareness of sports as a social phenomenon among the Chinese public. Sports are traditionally considered more masculine, and women often face disadvantages in sports (Messner, 2011), with gender inequalities in sports still prevalent (Chalabaev et al., 2013; Wellard, 2016). The sports selected from the pilot study generally had higher masculinity scores. Stereotypes on an individual level alone do not necessarily result in prejudice and discrimination, as this study concluded that the impact of evaluations may not be externalized into action, but they are reflective of the subconscious connections prevalent in society and culture (Hinton, 2017). Models are valuable in many fields characterized by negative gender stereotypes (Midgley et al., 2021). For instance, STEM students prefer faculty who motivate them to continue their careers (Ortiz-Martínez et al., 2023). Fortunately, there have been many efforts to increase female representation in many fields (Greider et al., 2019), and significant policy attention (Edmunds et al., 2016). However, continued interventions in this area are needed (e.g., Leippe and Eisenstadt, 1994; Mackie et al., 1992). We believe that the field of sports is also an important area for change.

The relationship between physical education and gender traits has contributed to the reform of physical education and the development of healthy self-perceptions among children and adolescents. Research and practice have shown that boys value strength, athleticism, and masculinity, whereas girls consider looks, body attributes, and femininity much more important (Klomsten et al., 2005). In contrast, the physical health of children and adolescents is at risk, and there are gender differences in health between boys and girls (Dong et al., 2019). Physical activity is perhaps the best intervention to remedy these issues. Additionally, physical education should encourage self-directed sports rather than forced sports. Most children choose to conform to stereotypes, but some are brave enough to break them (Rogers, 2020). Children can be educated to be more aware of gender and sexism (Lamb et al., 2009; Pahlke et al., 2014). There is nothing wrong with having boys participate in masculine sports and girls participate in feminine sports. However, future physical education curricula should be designed to emphasize gender inclusiveness and explicitness, as well as values and goals (Connell, 2008).

Conclusions

China has a unique culture and unique gender issues. Sport–gender stereotypes remained stable in China in the Global South and influenced impression evaluations, both targets and evaluators jointly influence the process, and there are gender differences. Both explicitly and implicitly, targets that were consistent with sport–gender stereotypes were perceived to have more gender-specific traits than the inconsistent targets. There was an experimental separation between these stereotypes and general gender stereotypes. Stereotype-consistent sports led the targets to be assessed as more masculine, and the evaluations were harsh toward women. Implicitly, sports acted as a buffer for social cognition. This work contributes to the discussion about not treating people differently just because they choose different sports, and gender must not be an obstacle.

Data availability

The authors confirm that all data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files. Deidentified data are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author(s) for academic research.

References

Amodio DM (2014) The neuroscience of prejudice and stereotyping. Nat Rev Neurosci 15(10):670–682. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3800

Banerjee P, Connell R (2018) Gender theory as southern theory. In: Risman B, Froyum C, Scarborough W (eds) Handbook of the sociology of gender. Handbooks of sociology and social research. Springer, Cham

Bian L, Leslie SJ, Cimpian A (2017) Gender stereotypes about intellectual ability emerge early and influence children’s interests. Science 355(6323):389–391. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aah6524

Boiché J, Chalabaev A, Sarrazin P (2014) Development of sex stereotypes relative to sport competence and value during adolescence. Psychol Sport Exerc 15(2):212–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2013.11.003

Bosak J, Eagly AH, Diekman AB, Sczesny S (2018) Women and men of the past, present, and future: evidence of dynamic gender stereotypes in Ghana. J Cross Cult Psychol 49(1):115–129. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022117738750

Bosak J, Kulich C, Rudman L, Kinahan M (2018) Be an advocate for others, unless you are a man: backlash against gender–atypical male job candidates. Psychol Men Masc 19(1):156–165. https://doi.org/10.1037/men0000085

Breen AB, Karpinski A (2013) Implicit and explicit attitudes toward gay males and lesbians among heterosexual males and females. J Soc Psychol 153(3):351–374. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2012.739581

Brinkschulte M, Furley P, Memmert D (2020) English football players are not as bad at kicking penalties as commonly assumed. Sci Rep 10(1):1–5. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-63889-6

Burrow S (2018) Recognition, respect and athletic excellence. Sport Eth Philos 14(1):76–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/17511321.2018.1539510

Cambon L, Yzerbyt VY (2017) Compensation is for real: evidence from existing groups in the context of actual relations. Group Process Intergroup Relat 20(6):745–756. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430215625782

Carrigan T, Connell B, Lee J (1985) Toward a new sociology of masculinity. Theor Soc 14:551–604. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00160017

Caspi A, Roberts BW, Shiner RL (2005) Personality development: stability and change. Annu Rev Psychol 56:453–484. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141913

Chalabaev A, Sarrazin P, Fontayne P, Boiché J, Clément–Guillotin C (2013) The influence of sex stereotypes and gender roles on participation and performance in sport and exercise: review and future directions. Psychol Sport Exerc 14(2):136–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2012.10.005

Colley A, Berman E, Millingen L (2005) Age and gender differences in young people’s perceptions of sport participants. J Appl Soc Psychol 35(7):1440–1454. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2005.tb02178.x

Connell RW (2005) Masculinities, 2nd edn. Polity, Cambridge

Connell R (2008) Masculinity construction and sports in boys’ education: a framework for thinking about the issue. Sport Educ Soc 13(2):131–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573320801957053

Connell R (2009) Gender in world perspective, 2nd edn. Polity, Cambridge

Connell R (2020) Southern theory: the global dynamics of knowledge in social science. Routledge, London

Cooley E, Payne BK, Loersch C, Lei R (2015) Who owns implicit attitudes? Testing a metacognitive perspective. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 41(1):103–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167214559712

Dados N, Connell R (2012) The global south. Contexts 11(1):12–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536504212436479

Derous E, Ryan AM, Serlie AW (2015) Double jeopardy upon resumé screening: when Achmed is less employable than Aïsha. Pers Psychol 68(3):659–696. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12078

Dong Y, Lau PW, Dong B et al. (2019) Trends in physical fitness, growth, and nutritional status of Chinese children and adolescents: a retrospective analysis of 1.5 million students from six successive national surveys between 1985 and 2014. Lancet Child Adolesc 3(12):871–880. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30302-5

Dufur MJ, Linford MK (2010) Title IX: consequences for gender relations in sport. Sociol Compass 4:732e748. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.17519020.2010.00317.x

Eagly A, Wood W (2012) Social role theory. In: Van Lange PAM, Kruglanski AW, Higgins ET (eds) Handbook of theories of social psychology, vol 42. Sage Publications Ltd, pp. 458–476

Eagly AH (1987) Sex differences in social behavior. A social–role interpretation. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, London

Eagly AH, Nater C, Miller DI, Kaufmann M, Sczesny S (2020) Gender stereotypes have changed: a cross-temporal meta-analysis of U.S. public opinion polls from 1946 to 2018. Am Psychol 75(3):301–315. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000494

Eagly AH, Steffen VJ (1984) Gender stereotypes stem from the distribution of women and men into social roles. J Pers Soc Psychol 46(4):735–754. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.46.4.735

Edmunds LD, Ovseiko PV, Shepperd S, Greenhalgh T, Frith P, Roberts NW, Pololi LH, Buchan AM (2016) Why do women choose or reject careers in academic medicine? A narrative review of empirical evidence. Lancet 388(10062):2948–2958. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01091-0

Eliot L, Ahmed A, Khan H, Patel J (2021) Dump the “dimorphism”: comprehensive synthesis of human brain studies reveals few male–female differences beyond size. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 125:667–697. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.02.026

Ellemers N (2018) Gender stereotypes. Annu Rev Psychol 69(1):275–298. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-122216-011719

Fang G (2008) The study on masculinities and men’s movement. Shandong People’s Publisher Press, Shandong

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A (2007) G* Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 39(2):175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146

Glick P, Fiske ST (1996) The ambivalent sexism inventory: different iating hostile and benevolent sexism. J Pers Soc Psychol 70(3):491–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.3.491

Glick P, Fiske ST, Mladinic A, Saiz JL, Abrams D, Masser B, Adetoun B, Osagie JE, Akande A, Alao A, Annetje B, Willemsen TM, Chipeta K, Dardenne B, Dijksterhuis A, Wigboldus D, Eckes T, Six–Materna I, Expósito F, López WL (2000) Beyond prejudice as simple antipathy: hostile and benevolent sexism across cultures. J Pers Soc Psychol 79(5):763–775. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.5.763

Greenwald AG, Banaji MR, Rudman LA, Farnham SD, Nosek BA, Mellott DS (2002) A unified theory of implicit attitudes, stereotypes, self-esteem, and self-concept. Psychol Rev 109(1):3–25. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.109.1.3

Greenwald AG, Lai C (2020) Implicit social cognition. Annu Rev Psychol 71:419–445. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010419-050837

Greenwald AG, Nosek BA, Banaji MR (2003) Understanding and using the implicit association test: I. An improved scoring algorithm. J Pers Soc Psychol 85(2):197–216. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.197

Greider CW, Sheltzer JM, Cantalupo NC, Copeland WB, Dasgupta N, Hopkins N, Wong JY (2019) Increasing gender diversity in the STEM research workforce. Science 366(6466):692–695. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaz0649

Guo J, Marsh HW, Parker PD, Dicke T, Van Zanden B (2019) Countries, parental occupation, and girls’ interest in science. Lancet 393(10171):e6–e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30210-7

Gurung RA, Chrouser CJ (2007) Predicting objectification: do provocative clothing and observer characteristics matter. Sex Roles 57(1):91–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-007-9219-z

Gülgöz S, Gomez EM, DeMeules MR, Olson KR (2018) Children’s evaluation and categorization of transgender children. J Cogn Dev 4:1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/15248372.2018.1498338

Hardin M, Greer JD (2009) The influence of gender-role socialization, Media use and sports participation on perception of gender appropriate sports. J Sport Behav 32(2):207–226. https://www.proquest.com/openview/5bee287df2238972505b3c32f434e3b1/1?pq–origsite=gscholar&cbl=30153

Haris MJ, Upreti A, Kurtaran M, Ginter F, Lafond S, Azimi S (2023) Identifying gender bias in blockbuster movies through the lens of machine learning. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10:94. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01576-3

Hermann JM, Vollmeyer R (2016) “Girls should cook, rather than kick!”—female soccer players under stereotype threat. Psychol Sport Exerc 26:94–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2016.06.010

Hilton JL, von Hippel W (1996) Stereotypes. Annu Rev Psychol 47(1):237–271. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.47.1.237

Hinton P (2017) Implicit stereotypes and the predictive brain: cognition and culture in “biased” person perception. Palgrave Commun 3:17086. https://doi.org/10.1057/palcomms.2017.86

Hively K, El–Alayli A (2014) “You throw like a girl:” the effect of stereotype threat on women’s athletic performance and gender stereotypes. Psychol Sport Exerc 15(1):48–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2013.09.001

Hofmann W, Gawronski B, Gschwendner T, Le H, Schmitt M (2005) A meta-analysis on the correlation between the Implicit Association Test and explicit self–report measures. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 31(10):1369–1385. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167205275613

Iacoviello V, Valsecchi G, Berent J, Borinca I, Falomir–Pichastor JM (2021) The impact of masculinity beliefs and political ideologies on men’s backlash against non-traditional men: the moderating role of perceived men’s feminization. Int Rev Soc Psychol 34(1):1–16. https://doi.org/10.5334/irsp.588

Jerald MC, Ward LM, Moss L, Thomas K, Fletcher KD (2017) Subordinates, sex objects, or sapphires? Investigating contributions of media use to Black students’ femininity ideologies and stereotypes about Black women. J Black Psychol 43(6):608–635. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095798416665967

Jia S, Qiu M, Cai R, Chen Q (2006) Research on gender difference of consciousness and behavior of physical exercise among college students in Hebei province. J Beijing Sport Univ 29(1):42–44. https://doi.org/10.19582/j.cnki.11-3785/g8.2006.01.015

Joel D, Berman Z, Tavor I, Wexler N, Gaber O, Stein Y, Liem F (2015) Sex beyond the genitalia: the human brain mosaic. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112(50):15468–15473. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1509654112

Klomsten AT, Marsh HW, Skaalvik EM (2005) Adolescents’ perceptions of masculine and feminine values in sport and physical education: a study of gender differences. Sex Roles 52(9):625–636. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-005-3730-x

Knight JL, Giuliano TA (2001) He’s a Laker; she’s a “looker”: the consequences of gender-stereotypical portrayals of male and female athletes by the print media. Sex Roles 45(3):217–229. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1013553811620

Koivula N (1995) Ratings of gender appropriateness of sports participation: effects of gender-based schematic processing. Sex Roles 33(7):543–557. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01544679

Kurdi B, Ratliff KA, Cunningham WA (2020) Can the implicit association test serve as a valid measure of automatic cognition? A response to Schimmack. Perspect Psychol Sci 16(2):422–434. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620904080

Lamb LM, Bigler RS, Liben LS, Green VA (2009) Teaching children to confront peers’ sexist remarks: implications for theories of gender development and educational practice. Sex Roles 61(5):361–382. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-009-9634-4

Lane KA, Kang J, Banaji MR (2007) Implicit social cognition and law. Annu Rev Law Soc Sci 3:427–451. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.lawsocsci.3.081806.112748

Leippe MR, Eisenstadt D (1994) Generalization of dissonance reduction: decreasing prejudice through induced compliance. J Pers Soc Psychol 67(3):395–413. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.67.3.395

Lemm KM, Dabady M, Banaji MR (2005) Gender picture priming: It works with denotative and connotative primes. Soc Cogn23(3):218–241. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.2005.23.3.218

Li J (2013) Gender differences and roles in Confucianism. Soc Sci Yunnan 1:61–65. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-8691.2013.01.012

Liu X (2012) Sport gender stereotypes and their intervention. Dissertation, Soochow University

Liu X, Zuo B (2006) Psychological mechanism of maintaining gender stereotypes. Adv Psychol Sci 14(3):456–461. https://en.cnki.com.cn/Article_en/CJFDTOTAL-XLXD200603022.htm

Louie K (2002) Theorising Chinese masculinity: society and gender in China. Cambridge University Press, London

Mackie DM, Allison ST, Worth LT, Asuncion AG (1992) The generalization of outcome-biased counter-stereotypic inferences. J Exp Soc Psychol 28(1):43–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031(92)90031-E

MacNell L, Driscoll A, Hunt AN (2015) What’s in a name: exposing gender bias in student ratings of teaching. Innov High Educ 40(4):291–303. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-014-9313-4

Matteo S (1988) The effect of gender-schematic processing on decisions about sex-inappropriate sport behavior. Sex Roles 18(1):41–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00288016

McKinnon M, O’Connell C (2020) Perceptions of stereotypes applied to women who publicly communicate their STEM work. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 7:160. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00654-0

Messner M (2011) Gender ideologies, youth sports, and the production of soft essentialism. Sociol Sport J 28(2):151–170. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.28.2.151

Midgley C, DeBues–Stafford G, Lockwood P, Thai S (2021) She needs to see it to be it: the importance of same-gender athletic role models. Sex Roles 85(3):142–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-020-01209-y

Nezlek JB, Krohn W, Wilson D, Maruskin L (2015) Gender differences in reactions to the sexualization of athletes. The J Soc Psychol 155(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2014.959883

Nosek BA, Banaji MR, Greenwald AG (2002) Harvesting implicit group attitudes and beliefs from a demonstration web site. Group Dyn–Theor Res 6(1):101–115. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2699.6.1.101

Nosek BA, Smyth FL (2011) Implicit social cognitions predict sex differences in math engagement and achievement. Am Educ Res J 48(5):1125–1156. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831211410683

Nosek BA, Smyth FL, Hansen JJ, Devos T, Lindner NM, Ranganath KA, Banaji MR (2007) Pervasiveness and correlates of implicit attitudes and stereotypes. Eur Rev Soc Psychol 18(1):36–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463280701489053

Nosek BA, Smyth FL, Sriram N, Nicole M, Lindner, Devos T, Ayala A, Bar–Anan Y, Bergh R, Cai HJ, Gonsalkorale K, Kesebir S, Maliszewsk N, Neto F, Olli E, Park J, Steele (2009) National differences in gender-science stereotypes predict national sex differences in science and math achievement. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106(26):10593–10597. https://doi.org/10.2307/40483597

Nowicki EA, Lopata J (2017) Children’s implicit and explicit gender stereotypes about mathematics and reading ability. Soc Psychol Educ 20(2):329–345. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-015-9313-y

Ortiz-Martínez G, Vázquez-Villegas P, Ruiz-Cantisani MI, Delgado-Fabián M, Conejo-Márquez DA, Membrillo-Hernández J (2023) Analysis of the retention of women in higher education STEM programs. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10:101. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01588-z

Osgood CE, Suci GJ, Tannenbaum PH (1957) The measurement of meaning. University of Illinois Press, Champaign

Pahlke E, Hyde JS, Allison CM (2014) The effects of single-sex compared with coeducational schooling on students’ performance and attitudes: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 140(4):1042–1072. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035740

Palumbo R, Adams Jr RB, Hess U, Kleck RE, Zebrowitz L (2017) Age and gender differences in facial attractiveness, but not emotion resemblance, contribute to age and gender stereotypes. Front Psychol 8:1704. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01704

Pickles J (2021) Gender: in world perspective 4th edition by Raewyn Connell—book review by James Pickles. Gend Work Organ 29(1):368–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12738

Plaks JE, Stroessner SJ, Dweck CS, Sherman JW (2001) Person theories and attention allocation: preferences for stereotypic versus counterstereotypic information. J Pers Soc Psychol 80(6):876–893. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.80.6.876

Plaza M, Boiché J, Brunel L, Ruchaud F (2017) Sport = male… But not all sports: Investigating the gender stereotypes of sport activities at the explicit and implicit levels. Sex Roles 76(3):202–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-016-0650-x

Prentice DA, Carranza E (2002) What women and men should be, shouldn’t be, are allowed to be, and don’t have to be: the contents of prescriptive gender stereotypes. Psychol Women Q 26(4):269–281. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-6402.t01-1-00066

Pringle R (2005) Masculinities, sport and power: a critical comparison of Gramscian and Foucauldian inspired theoretical tools. J Sport Soc Issues 29(3):256–278. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723505276228

Qian M, Wang Y, Wong WI, Fu G, Zuo B, VanderLaan DP (2021) The effects of race, gender, and gender-typed behavior on children’s friendship appraisals. Arch Sex Behav 50(3):807–820. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-020-01825-5

Régner I, Thinus–Blanc C, Netter A, Schmader T, Huguet P (2019) Committees with implicit biases promote fewer women when they do not believe gender bias exists. Nat Hum Behav 3(11):1171–1179. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-019-0686-3

Ren X (2020) On the implicit and solid structure of the gender difference in traditional China. J Chin Humanit 377(2):128–136+167–168. https://doi.org/10.16346/j.cnki.37-1101/c.2020.02.10

Reuben E, Sapienza P, Zingales L (2014) How stereotypes impair women’s careers in science. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111(12):4403–4408. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1314788111

Roberts SO (2022) Descriptive-to-prescriptive (D2P) reasoning: an early emerging bias to maintain the status quo. Eur Rev Soc Psychol 33(2):289–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463283.2021.1963591

Rogers LO (2020) “I’m kind of a feminist”: using master narratives to analyze gender identity in middle childhood. Child Dev 91(1):179–196. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13142

Rowe D (1998) Play up: rethinking power and resistance in sport. J Sport Soc Issues 22:241–251. https://doi.org/10.1177/019372398022003002

Rudman LA, Greenwald AG, Mcghee DE (2001) Implicit self-concept and evaluative implicit gender stereotypes: self and ingroup share desirable traits. Pers Soc Psychol B 27(9):1164–1178. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167201279009

Saini A (2020) Stereotype threat. Lancet 395(10237):1604–1605. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31139-9

Sherman JW, Hamilton DL (1994) On the formation of interitem associative links in person memory. J Exp Soc Psychol 30(3):203–217. https://doi.org/10.1006/jesp.1994.1010

Sidanius J, Hudson ST, Davis G, Bergh R (2018) The theory of gendered prejudice: a social dominance and intersectionalist perspective. In: Alex M, Lesley GT (eds) The Oxford handbook of behavioral political science. Oxford Academic, Oxford

Solmon MA (2014) Physical education, sports, and gender in schools. Adv Child Dev Behav 47:117–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.acdb.2014.04.006

Song J, Zuo B, Wen F, Tan X, Zhao M(2017) (2017) The effect of crossed categorization on stereotype-wealth × age group Psychol Explor 37(2):155–160 https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTotal-XLXT201702009.htm

Steffens MC, Jelenec P, Noack P (2010) On the leaky math pipeline: comparing implicit math-gender stereotypes and math withdrawal in female and male children and adolescents. J Educ Psychol 102(4):947–963. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019920