Abstract

This study investigates the production and comprehension of subject relative clause (SRC) and object relative clause (ORC) in English by Chinese EFL learners. Two experiments are reported. Using a sentence completion task to elicit the production of relative clauses (RCs), Experiment 1 examined the distributional patterns of SRC and ORC and showed that SRC was more frequently distributed than ORC. In addition, animacy and verb type had effects on the asymmetric distribution of SRC and ORC. Using a word-by-word moving-window self-paced reading paradigm, Experiment 2 further compared reading times (RTs) of SRC and ORC containing different animacy and verb type configurations. Reading difficulties in ORC were observed, and comprehension difficulties of certain configurations of animacy and verb type just mirrored their frequencies in the first experiment. Taken together, the processing asymmetry of SRC and ORC has been observed in both comprehension and production processes. Comprehension difficulties are believed to stem from the asymmetric distributions of sentence patterns involving different animacy and verb type configurations. These findings suggest that comprehension difficulties are correlated with the distributional patterns, which could provide strong support to the Production-Distribution-Comprehension account, the experience-based approach applicable in language acquisition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

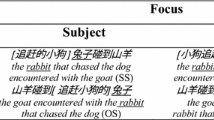

Relative clauses (RCs), also known as attributive clauses, are the most complicated recursive sentences existing universally and are frequently used in daily life. As studies on the cognitive processes of RCs would shed light on human cognitive processes, mechanisms underlying the processing of RC sentences have aroused great interest among scholars (Miller and Chomsky, 1963). One of the hot topics that has attracted increasing attention from researchers worldwide is the processing asymmetry between SRC and ORC. When the head noun is the subject of the verb in the relative clause, it is called an SRC (1a); when the head noun is the object of the verb in the relative clause, it is called an ORC (1b). It is a well-documented finding that SRCs are easier to process than ORCs (e.g., Homles and O’Regan, 1981; King and Just, 1991; Caplan et al., 1998; Yang et al., 2013).

(1a) The senator that ○ bothered the reporter caused a big scandal.

(1b) The senator that the reporter bothered ○ caused a big scandal.

A variety of theories have been proposed to explain this phenomenon. Structure-based accounts explain SRC preference in terms of syntactic factors, emphasizing a universal preference for syntactic gaps in the subject position. Noun Phrase Accessibility Hierarchy Hypothesis (NPAH) (Keenan and Comrie, 1977) belongs to this category. Based on the comprehensive analysis of more than 77 languages, Keenan and Comrie (1977) proposed an implicational scale for relativizability of different grammatical roles. According to the scale all languages adhere to the following scale:

This hypothesis proposes that all languages having a relativizing strategy can relativize on subjects; that all those which can relativize on direct objects can also relativize on subjects; and that all that can relativize on indirect objects can relativize on direct objects and subjects, and so on, down the hierarchy. To test the hypothesis, Keenan and Comrie (1977) investigated the inherent naturalness of subject relativization by examining the frequency of relative clauses along the hierarchy in English written text. They found that SRCs were more common than direct ORCs. Many studies have provided evidence for the hypothesis, showing that relativization on subjects was most frequent and popular in the languages that they had examined, followed by objects, obliques, and other grammatical roles on the scale (e.g., Pavesi, 1986; Izumi, 2003; Kuo and Vasishth, 2006; Li and Wang, 2007).

In contrast to syntactic approaches, working memory-based approaches rely on functional factors to account for the asymmetry between processing SRC and ORC, proposing that the storage of incomplete head-dependencies in phrase structure causes complexity to increase in object relative sentences compared with subject relative sentences (Miller and Chomsky, 1963; Lewis, 1996). The Dependency Locality Theory (DLT) falls into this category, which assumes that human parsing systems consume computational resources available in working memory while keeping track of syntactic predictions over a nonlocal distance. The cost of processing is measured in two dimensions: the storage cost of holding incomplete syntactic heads in memory (measured in memory units, MU) and the integration cost of integrating the current word into an existing structure (measured in energy units, EU). For RCs in English, the DLT predicts that object-extracted RCs are cognitively more demanding than subject-extracted RCs because, in terms of memory load, ORCs contain more temporarily incomplete dependencies after the head noun than SRCs. In terms of the integration cost, the linear distance between the filler and the gap is longer in ORCs than in SRCs (Gibson, 1998). To sum up, according to Gibson’s DLT, sentence processing is constrained by limited computational resources in working memory, which is quantified in terms of integration and storage cost.

DLT can account for a wide range of cross-linguistic data, including English (e.g., Warren and Gibson, 1999), Japanese (Babyonyshev and Gibson, 1999), and Chinese (Yang et al., 2010). Yang et al. (2010) conducted an ERP study to examine the neural correlate of processing Chinese RCs. The ERP data showed that more left-lateralized anterior regions of a frontal-temporal network became active when the thematic role specification for multiple referents may have required additional cognitive and memory resources. It indicated that the processing of such multiple referents consumed more computational resources when integrating more complex elements into the structures, thus supporting the notion of DLT.

However, some scholars argued that it was not always the case, in particular, ORC sentence pairs like (2a) and (2b). Traxler et al. (2002) and Mak et al. (2002, 2006) found that ORCs with inanimate heads were easier to process (2a) than ORCs with animate head nouns (2b). They vary only in the animacy of the head noun and thus tax the same amount of memory load, so the asymmetry would also be affected by other factors, such as properties of the nouns and verb type in the embedded clause (Mak et al., 2002; Traxler et al., 2005). Their findings could be explained neither by syntactic-based theories nor by memory-based theories.

(2a) The climate that the scientist studied annoyed us.

(2b) The children that the scientist studied annoyed us.

Evidence has shown that experience-based approaches are effective in explaining these facts. The framework of Production-Distribution-Comprehension (PDC) attempts to link properties of the language production system to particular choices made during utterance production, to link those choices to particular distributional regularities in the input provided to comprehenders, and finally, to show that comprehension behavior is modulated by these distributional regularities (Gennari and MacDonald, 2009). In a word, it links production and comprehension.

As to sentence processing, the PDC claims that the production mechanisms determine structure choices, which results in robust distributional patterns in the language. Exposed to the input, language learners learn them over time, and then these distributional patterns become the probabilistic constraints guiding the comprehension process in a constraint-based system. In line with this view, comprehension difficulties have been observed to be correlated to distributional patterns in language use, which are themselves emergent from production mechanisms. In sentence production, the choice of word order and syntactic structure is strongly constrained by accessibility which is determined by word length, word frequency, or concept salience (e.g., Bock, 1987; Gennari and MacDonald, 2009).

A number of studies have supported this approach (e.g., Bybee, 2002; Reali and Christiansen, 2007), and there are also some studies that are inconsistent with the account. Gibson (2013) found that SRCs are more difficult to process than ORCs, while SRCs are more common in Chinese. Though studies have suggested that memory-based approaches and syntactic approaches are not independent of prior experience, it needs to be tested (Hsiao and MacDonald, 2013; MacDonald and Christiansen, 2002). In addition, some argue that it is unlikely that the pattern applies to L2 learners because statistical information in naturalistic L1 production cannot be a reliable indicator of L2 learners’ language experience. So it is quite interesting to investigate the factors that complicate the processing difficulties and the theories which are more robust in predicting the difficulties.

Previous studies showed that the animacy effect on the comprehension process of RCs was correlated to the frequency of the animacy configurations in production (e.g., Mak et al., 2006). Animate head SRCs are more frequent than inanimate head ones, while inanimate head ORCs are more frequent than animate head ones. The asymmetric distribution of animate and inanimate head nouns in SRCs and ORCs results in the processing asymmetry between SRCs and ORCs. SRCs with animate head nouns are easier to process than those with inanimate head nouns, and difficulties of processing ORCs with inanimate head nouns would be reduced for the higher frequency of this type of sentence in the corpus (e.g., Mak et al., 2002; Roland et al., 2007).

Apart from nouns, properties of verbs, especially embedded verbs, also play a crucial role in RC processing. The verb is closely tied to the thematic role assignment of the head noun and the embedded noun, and the thematic roles that nouns play in the event indicated by verbs would modulate the accessibility of the elements. Constraints during utterance planning give rise to production choices in which certain types of verbs and nouns co-vary with a particular choice of active or passive structure within the relative clause, resulting in a particular mapping from event roles to syntactic arguments. If the expression does not match such a mapping, comprehension difficulties will arise.

There are only a few investigations studying verb types till now. Ferreira (1994) studied how verbs’ thematic roles exerted effects on the rate of active and passive sentence production, in which two types of verbs were examined: the agent-theme, such as attack, and the theme-experiencer, such as delight. The latter type tends to be passivized more frequently than the former because the role of experiencer is more prominent than the role of theme-cause, which leads to passive constructions, locating the most conceptually prominent noun in the subject position. While for the agent-theme verbs, the agent usually takes the subject position, resulting in an active construction. Gennari and MacDonald (2009) examined the effects of two types of verbs, the agent-theme and the theme-experiencer, on RC processing. They found similar effects of verb type on RC processing.

The overview of previous studies showed that the PDC account has not been fully testified. The processing advantage of SRC was not consistent, being mainly proved among the L1 speakers. Investigations among L2 English learners were scarcer, especially the Chinese EFL learners. Some studies have found that SRCs are easier for both first-language (L1) children and second language (L2) adults (e.g., Doughty, 1991; Eckman et al., 1988; Gass, 1979; Keenan and Hawkins, 1987). However, the Chinese relative clause is typologically unique for its being head-final rather than head-initial, and the power of animacy over sentence processing is evident. It remains to be investigated whether the big contrast will lead to different patterns in the processing of relative clauses in Chinese English learners. In addition, verb type and the interactive effects of animacy and verb type on RC processing are still unraveled. Finally, the investigation of whether the asymmetry would be changed and how it changes with different configurations of animacy and verb type will help to verify and expand the PDC account.

In light of this, the present study attempted to verify the PDC account by exploring the relationship between distributional regularities and processing difficulties, examining the effects of animacy and verb type on both the distributional regularities and comprehension processes. The research questions are as follows: (1) What are the production patterns of English RCs in Chinese EFL learners? Does animacy and verb type have an effect on it? (2) What are the patterns of English RCs processing in Chinese EFL learners? Is the processing difficulty of a certain structure related to its distributional pattern (i.e. frequency) in the language? Specifically, two experiments were conducted to examine the production and comprehension processes of RCs with different noun animacy and verb types, respectively.

Experiment 1

Participants

The participants were 35 non-English major undergraduate students from the PLA Information Engineering University in Henan, China (21 males and 14 females) aged 19–21 years (M = 20.1, SD = 0.7). They had a similar experience in English learning, and all the participants had passed College English Test, Band 4 (CET-4), with an average score of 589.3 (SD = 61.03) out of a total score of 710. CET-4 is a normalized English test taken by all non-English major college students and administrated by the Ministry of Education in China. All participants reported right-handedness. All the participants signed the written consent, and after the experiment, they were offered due payments for their participation.

Experimental design

The dependent variable of the experiment was the frequency of various types of RC, and the independent variables were the animacy (animate vs. inanimate) and verb type (agent-theme vs. theme-experiencer), both of which were within-subject variables. Three types of RCs were explored, SRC, ORC, and passive RC (PRC, e.g., The officer that was amused by the joke was very interesting.). PRC was singled out as a special type of SRC; in doing so, it was more convenient for us to discuss the effects of verb type on the choice of voice in production.

Materials

The experimental stimuli were 48 sets of incomplete sentences used in previous studies (Traxler et al., 2002; Gennari and MacDonald, 2008), with a few slight modifications, i.e., the substitution of some low-frequency and unfamiliar words to ensure a better understanding of the experimental materials among Chinese EFL learners. They were evenly divided into two parts, Part A and Part B. Part A was made up of 36 items, 12 items with animate head nouns, and another 12 with animate head nouns as well, but the order of the embedded noun and verb was reversed across the two conditions; in this way, the potential influence of the word order could be ruled out. And the remaining 12 items have inanimate head nouns, which were designed to investigate the effect of animacy on RC production. As to the last 12 items with inanimate head nouns, gated sentence completion was employed, in which only the head noun was given. The participants were asked to complete the sentence with a relative clause (see Table 1). Part B consisted of 24 sets of sentences, 4 conditions for each set, which were designed to examine the effect of verb type on the production of RC. We varied them within two verb types, the agent-theme and the theme-experiencer, the head noun and the embedded noun being animate nouns. The order of the given noun and verb for the relative clause was reversed; thus, four conditions were constructed for each set (see Table 1). To prevent the participants from guessing the experimenters’ intentions, the items of Part A and Part B were intermixed and randomized.

Data collection and coding

The materials were printed on A4 papers and handed out to the participants who were seated in a quiet classroom. The participants were randomly assigned to one list of each set of items from the two parts and were required to complete them independently. To guarantee that the participants could finish all the items, no time limit was set for them to complete the task. Thirty-five test papers were handed out, and all the papers were collected. Then we coded the sentence completions. Non-relative clauses or relative clauses not complying with the grammatical rules were removed from the data. The valid data of the extracted type of the RC, the animacy of the head noun, and the verb type of the embedded clause were coded. Errors irrelevant to the relative clause were ignored, such as errors in agreement, spelling, tense, and collocation. All the coding was conducted by the authors and another experienced English teacher, with the interrater reliability being up to 0.96.

Results

The data were analyzed with the help of SPSS 19.0. Frequencies for the three types of RC were calculated. Specifically, the frequencies for SRC, ORC, and PRC were 572, 420, and 325, respectively. When the frequency of PRC was added to that of SRC, the total frequency of SRC (897) was far more than that of ORC. Chi-square test was run to determine the significance, and the results indicated that SRC was significantly predominant than ORC (x2 = 70.72, p = 0.000). Thus, it is reasonable to conclude that the distribution of SRC and ORC is asymmetric.

With regard to the animate head noun, the frequencies of SRC and ORC differed greatly. The frequency of SRCs was 238 (84.7% of responses) and significantly exceeded the frequency of the 43 ORCs (15.3%) (x2 = 135.320, p = 0.000). While for the inanimate head noun, the frequency of SRC greatly decreased. Additionally, a significant difference was also observed between them (x2 = 4.693, p = 0.030). For the PRC, when the head noun was inanimate, its percentage was larger than its corresponding percentage when the head noun was animate (23.0 vs. 10.4%) (see Table 2).

The results suggested that the participants tended to assign the agent role to the animate subject, resulting in less probability of producing PRC and that they tended to assign the patient role to the inanimate subject, leading to higher frequencies for PRC. To be specific, the order based on the frequencies of the four types of RCs, namely, SRC and ORC with either animate or inanimate head noun, was as follows: (animate) SRC > (inanimate) ORC > (inanimate) SRC > (animate) ORC.

The results of the production for the incomplete sentences containing agent-theme verbs and theme-experiencer verbs were shown in the stacked area chart (see Fig. 1). The frequency of SRCs was 183 and 193, respectively, exceeding those of the ORC and PRC. The frequencies of SRC were predominant for both verb types, but there were differences between the frequencies of ORC and PRC. As to the sentences containing the agent-theme verbs, the frequency of SRC (183) far exceeded those of the other two types, the 96 ORCs and 89 PRCs (x2 = 44.712, p = 0.000), which were evenly distributed. However, for the sentences containing theme-experiencer verbs, SRC still dominated the total frequencies among the three types (x2 = 108.483, p = 0.000), whereas the frequencies of PRC and ORC had changed, with ORC decreasing to 34 and PRC increasing to 125. In terms of the frequency of PRC, there was some difference between L1 and L2 speakers. A vast majority of PRCs were produced by L1 speakers, while the percentage of PRCs by L2 speakers was lower, but the main production preference for theme-experiencer verbs was that they were more likely to be produced in passive constructions than agent-theme verbs.

Discussion

The results clearly answered the first question, showing that Chinese EFL learners have an overall tendency to produce more SRCs, resulting in the asymmetric distribution of SRCs and ORCs. At the same time, their structural preferences are modulated by verb type and animacy. When the head noun is animate, the use of SRCs is predominant; when it is inanimate, the frequency of ORCs increases sharply, which is consistent with the findings of previous studies (Gennari and MacDonald, 2009; Li and Wang, 2007). The results lend support to the concept that animacy is a general factor constraining RC production (Gennari and MacDonald, 2009; Mak et al., 2002). Regarding the effects of verb types, agent-theme verbs usually assign the animate nouns with the argument role of agent or instigator of the event and inanimate nouns with the patient; therefore, it is of higher probability for Chinese EFL learners to produce SRCs with agent-theme verbs. Theme-experiencer verbs require an experiencer, usually an animate object, at the earlier position of a sentence, which will undergo some psychological changes or other similar experiences. Consequently, the conjunction of the animate noun and theme-experiencer verb configuration usually tends to increase the production of PRCs. To be specific, theme-experiencer verbs are more frequently produced as passives than agent-theme verbs are. The lower percentage of PRC in L1 might be attributed to the lower frequency of the passive voice in Chinese. In sum, nouns and verbs have interactive effects on RC production.

Experiment 2

Experiment 1 examined both the general pattern regardless of animacy and verb type and the production preference under the impact of the abovementioned factors. The results showed that asymmetric distributional patterns existed among different types of RCs. Would these patterns have effects on the asymmetric processing of different types of RCs? To answer this question, the processing difficulties of RCs were examined in this experiment. The effects of animacy and verb type on the processing asymmetry were highlighted to test PDC.

Participants

A total of 38 college students from the PLA Information Engineering University in China participated in the experiment (22 males and 16 females). Their age ranged from 19 to 21 years, with an average age of 20.5 years (SD = 0.5). They were native Chinese speakers, and they had a similar experience in English learning. All the participants had passed CET-4 test, with an average score of 556.4 (SD = 58.2) out of a total score of 710. They reported right-handedness, and all of them signed the written consent. After the experiment, they were offered due payments for their participation.

Materials

The materials of this study were developed from those of Traxler et al. (2005). To match the language proficiency level of our participants, some possible new words were substituted with familiar words. Forty-four sets of critical stimuli of SRCs and ORCs with different animacy and verb type (agent-theme or theme-experiencer) were constructed, generating six conditions for each set. The animacy of the head noun and the embedded noun is the combination of animate and inanimate (see Table 3). Sixty filler sentences (containing structures with compound sentences and complex sentences) were intermixed with the stimulus items. Head nouns and embedded verbs were matched in frequency and word length, and no significant difference was found between the matched pairs (t (43) = 1.25, p = 0.068; t (43) = 1.96, p = 0.072). To ensure that the stimuli were not biased in terms of plausibility, we conducted a study in which an additional 15 students of similar language proficiency level with those participating in the formal experiment rated the plausibility of the experimental sentences on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = not plausible, 7 = very plausible). The results indicated that there was no significant difference between the plausibility of SRCs (M = 5.66, SD = 0.75) and ORCs (M = 5.83, SD = 0.64) (t = 1.13, p = 0.083).

Procedures

A word-by-word moving-window self-paced reading paradigm was used. Seated in a quiet room, the participants were required to do the self-paced reading task on their laptops. The stimuli were programmed and presented with the Linger Software. At the start of each trial, all the words of a sentence were replaced by dashes on the screen. The participants pressed the space bar to change the string of dashes into a word. Each time the key was pressed, the next word appeared, and the preceding word reverted back into dashes. The time between key-presses was recorded, which was the reading time for the preceding word. Immediately after reading the stimulus sentence, a Yes/No comprehension question related to the content of the sentence appeared on the screen. The participants were asked to judge whether the statement was true or false. If the answer was right, no response was given; if it was wrong, feedback saying that the answer was incorrect was given so as to arouse the participants’ attention to read more carefully. The participants were told to read at a normal speed, trying their best to understand the meaning of the sentence. Prior to the formal experiment, the participants completed 10 practice items with the help of the experimenter. The experiment lasted approximately for about an hour.

Results

We used the same criteria as used by Wells et al. (2009) and Gennari and MacDonald (2009), i.e., only RTs on the trials with correct responses to comprehension questions were included in the data analysis reported below. For each participant in each condition, items with reading times greater than 4000 ms, less than 50 ms, and beyond 2.5 standard deviations away from the mean per word position were removed. This procedure resulted in an average data loss of 2.13%. By reference to Gennari and MacDonald (2009), reading times for the two function words (i.e., by, the) in PRCs were removed to make them match the other conditions. Finally, we divided all the words of RCs into three main regions, namely, the NP region for the main clause (the+N+that), the embedded clause (NP+V or V+NP), and the matrix verb region of the main clause. The reading times of the three regions were the dependent variables. To investigate the comprehension difficulties of SRCs, ORCs, and PRCs, we first conducted a general analysis of the reading times and then explored the effects of animacy and verb type on the comprehension processes.

General analysis of the reading times

The reading times for SRCs and ORCs are presented in Table 4. Separate ANOVAs were conducted for each of the three dependent measures in the three regions and the total RTs. The results showed that the participants responded significantly faster to SRCs than to ORCs in the reading times at the embedded clause and matrix verb region. The differences between the RTs at the matrix verb region and the entire sentence were significant (matrix verb region: 544.12 ms vs. 722.80 ms, F (1, 37) = 52.11, p = 0.000; entire sentence: 4177.41 ms vs. 4349.50 ms, F (1, 37) = 7.22, p = 0.000). The 95% confidence intervals (matrix verb region: ±156.87 ms, entire sentence: ±169.23 ms) for these differences between different sentence types did not exceed the differences across the means at the matrix verb region and the entire sentence. The main verb is where the embedded clause and the main clause integrated, and more resources should be allocated to its processing. Consequently, the processing speed of the two sentence types at the matrix verb region was significantly different. The above results indicated that the reading times of SRCs were shorter than those of ORCs both for the entire sentence and at the matrix verb region, suggesting that the processing of SRCs was easier than that of ORCs.

The effects of animacy on the comprehension asymmetry of SRC and ORC

According to the reading times of the entire sentence, SRCs with animate head nouns were the easiest (M = 4022.71 ms), followed by ORCs with inanimate head nouns (M = 4182.14 ms), SRCs with inanimate head nouns (M = 4323.92 ms), and ORCs with animate head nouns (M = 4526.47 ms) as the most difficult. To be specific, when the head noun was animate, SRC was easier to process than ORC; when the head noun was inanimate, the processing of the ORC became easier than that of the SRC. A two-way ANOVA was conducted with the entire sentence reading time as the dependent variable. The results indicated that the main effect of sentence type was significant (F (1, 37) = 6. 04, p = 0.014), which was consistent with the findings of previous studies (Mak et al., 2002, 2006; Traxler et al., 2002). There was no significant main effect of animacy (F (1, 37) = 0. 08, p = 0.774), but the interaction between animacy and sentence type was significant (F (1, 37) = 8.78, p = 0.000). Simple effect tests probing this interaction revealed significant effects for animate head nouns (F (1, 37) = 17.42, p = 0.000) and no effects for inanimate head nouns (F (1, 37) = 2.81, p = 0.095).

For animate head nouns, the RTs of SRCs and ORCs began to diverge after the position of “that” and continued to the end, including the embedded clause and the main verb, and the difference became greater as sentences unfolded (see Fig. 2). The results of paired samples t-tests indicated the significance for the main verb reading time (t (37) = −7.023, p = 0.000). Whereas for inanimate head nouns, the processing difficulties were reversed in the reading times of SRCs and ORCs (see Fig. 3). The diagrams showed that RTs for the SRCs became longer than that for the ORCs and the divergence was mainly on the embedded clause (2056.72 ms vs. 1923.82 ms, t (37) = 2.512, p = 0.015).

The effects of verb type on the comprehension asymmetry of SRC and ORC

Given the constraints of argument roles, there were two sets of sentences that matched in terms of verb types: ORCs with animate head nouns and SRCs with inanimate head nouns. The RTs of the entire sentence and different regions for the two sets of sentences are shown in Tables 5 and 6, respectively. For the first distinctive pair, that is, ORCs with animate head nouns containing either the agent-theme verbs or the theme-experiencer verbs, the mean RTs for the entire sentence containing agent-theme verbs (4333.37 ms) were significantly shorter than those containing theme-experiencer verbs (4664.21 ms). The results of repeated measures ANOVAs with RTs as the dependent variables and with verb type as the factor indicated that RTs for the embedded clause were significantly different between sentences containing agent-theme verbs and those containing theme-experiencer verbs (F (1, 37) = 6.776, p = 0.000). The results showed that it was easier to process sentences containing agent-theme verbs. It was also suggested that processing differences do exist for this set of sentences, and the difference mainly lies in the embedded clause, which is the most complicated part in terms of argument structure.

As to the second set, namely SRCs with inanimate head nouns containing either the agent-theme verbs or the theme-experiencer verbs, the reading times for sentences containing theme-experiencer verbs in both the entire sentence and the two main regions (i.e., the NP and the matrix verb) were shorter than those containing agent-theme verbs. The differences in RTs at the matrix verb region between sentences containing theme-experiencer verbs and those containing agent-theme verbs were not significant (F (1, 37) = 1.708, p = 0.132). The results indicated that verb type had little effect on the processing of SRC. When the verb type effect met the subject preference effect, the latter prevailed, offsetting the former’s possible role.

Discussion

The results of this experiment show that the RTs of SRCs are generally shorter than those of ORCs; thus, the processing of SRCs is easier than that of ORCs. Moreover, processing difficulties are constrained by animacy and verb type of RC sentences. For the inanimate head nouns, the processing difficulties of ORCs are greatly reduced, and the processing preference of ORCs is mainly in the embedded clause, where it usually consumes many resources on the argument role assignment. In the course of online RC processing, recognizing the embedded verb will facilitate the processing of the embedded clause, for the embedded verb is the key to assigning the argument roles to both the head noun and the noun in the embedded clause. The results are not in accord with previous works on L1 speakers (Hale, 2001; Levy, 2008; Chen and Hale, 2021), which showed slower reading only at the embedded NP but not at the embedded verb. This may be due to L2 learners’ low proficiency in connecting the thematic role of the embedded NP and the following verb. The fixed chunk of NP and VP are not entrenched; therefore, they need more time to connect them.

There is also a little discrepancy with Traxler et al. (2005), whose findings show that inanimate sentential subjects greatly reduce the processing difficulty of ORC, but minimal differences were found between the processing of SRCs and ORCs with inanimate head nouns. The discrepancy may result from different experiment methods and participants. Traxler et al. (2005) conducted eye movement in native English speakers, while the present study employed self-paced reading in EFL learners. When the magnitude of the object-relative penalty is reduced, the effect is not obvious for native speakers on first-time regressions or total time. Compared with native speakers, Chinese learners of English are more sensitive to the semantic cues available to them. When the head noun of the ORC is inanimate, the embedded noun is human animate, and the semantic cue facilitates the rapid correct assignment of the nouns to argument positions; therefore, reading times were reduced to a great extent.

When processing ORCs which are only distinctive in verb type, processing differences do exist. Specifically, the processing difficulty for the sentences containing agent-theme verbs is smaller than that for the sentences containing theme-experiencer verbs. The main difference in comprehension difficulty is in the embedded clause, which is the most complicated part in terms of argument structure. However, when processing SRC pairs, the processing differences between the two sentences with different verb types are not significant, which testifies to the subject preference effect.

The present study and other previous studies indicating processing advantages of SRC and animacy effect could be explained neither from the memory-based approach nor from the syntactic approach. SRCs or ORCs with different animacy and verb type configurations bear the same syntactic complexity and tax the same amount of memory load, but the processing difficulty is not the same. The most plausible explanation might lie in prior experience; that is, the processing is impacted by the frequency of exposures to certain structures.

General discussion

Production mechanisms and distributional patterns

The results of Experiment 1 indicate that the frequency of SRCs is generally higher than that of ORCs in Chinese EFL learners’ sentence production tasks. This may be attributed to the fact that production complies with the principle of the easier, the more prioritized. Constructions, either words or structures, which are more accessible, tend to be retrieved easier from memory. SRCs are more accessible than ORCs, for the word order of SRCs is SVO—the common English sentence pattern, whereas the word order of ORCs is OSV. The reverted position of the object is less frequently used in English; thus, it is less accessible. Speakers tend to choose the easier one, so SRCs are usually more frequently used relative to ORCs in language production.

The results also indicate that animacy and verb type have effects on the distributional patterns of different types of RCs. When the head noun is animate, SRCs are predominant; when it is inanimate, the frequency of ORCs increases sharply. Speakers tend to take the perspective of animates, so animates tend to be mentioned before inanimates. People tend to take the perspective of the more active participant in the event, so agents tend to be mentioned earlier than other event participants. The Theory of Evolution may account for the effects of animacy. In the process of species evolution, various threats from other animals are constant, so it is necessary to monitor the surrounding environment. According to the Animate Monitoring Hypothesis, the human attention system shows different patterns in the face of animate objects and inanimate objects (New et al., 2007). As the animate object could change its ideas, actions, locations, and trajectories in a short period of time, it is essential to monitor it constantly. While the inanimate would not pose a threat, monitoring is unnecessary. Such a cognitive pattern based on biology is reflected in language, resulting in the animate entity being the instigator and the inanimate entity an undergoer in a sentence. As for an RC, an animate head noun is usually assigned with the argument role of an instigator, both in the main clause and in the embedded clause, which is mapped onto the subject position; thus, more SRCs are produced. On the contrary, inanimate head nouns are usually assigned a role of an undergoer, which results in the production of more ORCs.

Just as Gentner (1981) argued, an important aspect of verb meaning is its relation to the entities and objects that commonly participate in the events described by that verb, so the animacy of a noun determines the thematic role that will bear in the event described by the verb in a sentence. Consequently, thematic role knowledge is part of a verb meaning. Agent-theme verbs usually allocate the animate nouns with the role of agent or instigator of the event and inanimate nouns with the patient. Theme-experiencer verbs require an experiencer, usually an animate object, to be in the earlier position of a sentence, so animacy and verb type have an interactive effect on RC production.

Distributional regularities and comprehension mechanisms

The results of Experiment 2 show that the processing of SRCs is generally easier than that of ORCs, and additionally, animacy and verb type also exert influence on processing. SRCs’ being easier to process than ORCs only applies where the head noun is animate but does not apply where it is inanimate. The combination of animacy and verb type in RCs provides probabilistic information modulating the relative likelihood of an interpretation. Being exposed to the language, learners acquire such contingent probabilities, which affect their subsequent comprehension.

Thus, comprehension difficulties in different types of sentences are related to their distributional regularities. The distributional properties of nouns and verbs activate specific patterns of mapping the thematic roles to arguments, for example, animate nouns mapped onto subjects of actives. This is in agreement with the results of previous studies (Mak et al., 2002; Gennari and MacDonald, 2008, 2009), lending support to the role of frequency in RC processing. The finding that comprehension difficulties in processing are modulated by animacy and verb type fit the production patterns in Experiment 1. As to the inanimate head noun, the frequency of SRC is lower than that of ORC, so the comprehension of SRCs with inanimate head nouns is consequently not so easy as comprehending ORCs with inanimate head nouns. Another case is with the theme-experiencer verbs. Compared with the agent-theme verbs, theme-experiencer verbs are passivized more frequently, especially in the animate-inanimate configuration of the head noun and the embedded noun. As a result, when they are not passivized in the ORCs, comprehension of the structure becomes difficult because the experiencer for a theme-experiencer verb is usually mapped onto subjects of passives rather than objects of actives.

The results of the two experiments validate the PDC account, which proposes that distributional patterns of a certain structure could affect its comprehension process, showing that the comprehender’s prior experience plays the dominant role in interpreting RC sentence processing. It concurs with the usage-based accounts of sentence processing that structure emerges from use, and usage has an effect on language acquisition. When some words co-occur constantly, they would merge into a single unit, which becomes easier to access. As time goes on, such co-occurrence would be strengthened and entrenched in the learner’s mind as a unit to be represented. In a word, processing difficulties in utterance and evolutionary forces result in differential distributional patterns between SRCs and ORCs, which in turn is ascribed a large role to their processing difficulties. The results are testified by different sentence types with different animacy and verb types, and PDC is thus confirmed to be applicable to both native speakers and second language learners.

In a word, structure choices in production are determined to some extent by production-specific mechanisms, producing robust distributional regularities in the language. Comprehenders who are exposed to this input learn these regularities over time; then, these distributional patterns become the probabilistic constraints that guide the comprehension processes. As claimed by researchers, processing preferences are driven by the frequency of occurrence of particular sentence structures (Mak et al., 2006; Mitchell et al., 1995).

In this section, we have discussed how production mechanisms generate distributional regularities and the correlation between distributional regularities and comprehension difficulties. We do not maintain that frequency is the only constraint affecting the comprehension process; some other factors, such as discourse and referential information, cognitive limitations as well as L1 transfer due to cross-linguistic differences, also exert influences on the comprehension processes of SRCs and ORCs. However, we do believe that when words repeatedly co-occur in a specific order, such frequent sequential co-occurrence of linguistic elements may fuse into a single processing unit, and the repeated exposure to it would create a supra-lexical representation of this construction, making it easier to process.

Implication and conclusion

This study examined the processing asymmetry between SRCs and ORCs and the effects of animacy and verb type on it among Chinese EFL learners. The results show that SRCs and ORCs are generally distributed asymmetrically, with SRCs predominantly popular. However, when the head noun is inanimate, the asymmetry is reversed, with ORCs getting more frequent than SRCs. Similar effects are found with verb type, and the extent of asymmetry is reduced with the theme-experiencer verb. Such distributional regularities are driven by the accessibility of concepts, word orders, and role-to-argument mappings. Things that go against those favored by accessibility and other production mechanisms are more likely to fall out of use. Animate subjects are mapped with the argument of agent, and more SRCs are produced, and it is the same case with the agent-theme verb. As a consequence, the processing difficulty is found to mirror distributional patterns in the elicited data, which indicates that linguistic experiences have a great effect on language performance. Our results provide strong support to the PDC account, the experience-based approach being universally applicable to both L1 and L2 speakers.

The findings have implications for second language acquisition, suggesting that L2 learners follow the same pattern as L1 speakers in English RC processing. RC is a complicated grammatical item for Chinese learners of English. This study implies that when the prior experience of certain structures increases, the processing will become easier. So with enhanced input, Chinese learners of English can improve their comprehension ability. Limitations, meanwhile, should be pointed out. The present study only focuses on the effect of animacy and verb type on processing; future studies may include discourse factors, such as sentence complexity, plausibility, and indexical reference, and more advanced techniques like eye movement and ERP could be employed.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to them containing information that could compromise research participant privacy according to the confidentiality of the military academy but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Babyonyshev M, Gibson E (1999) The complexity of nested structures in Japanese. Language 75(3):423–450

Bock JK (1987) An effect of the accessibility of word forms on sentence structure. J Mem Lang 26(2):119–137

Bybee J (2002) Sequentiality as the basis of constituent structure. In: Givo´n T, Malle B (eds) The evolution of language out of pre-language. John Benjamins, Philadelphia, pp 107–132

Caplan D, Nathaniel A, Gloria W (1998) Effects of syntactic structure and propositional number on patterns of regional cerebral blood flow. J Cogn Neurosci 10(4):541–552

Chen Z, Hale JT (2021) Quantifying structural and non-structural expectations in relative clause processing. Cogn Sci 45(1):1–36

Doughty C (1991) Second language instruction does make a difference. Stud Second Lang Acquis 4(13):431–469

Eckman FR, Bell L, Nelson D (1988) On the generalization of relative clause instruction in the acquisition of English as a second language. Appl Linguist 9(1):1–20

Ferreira F (1994) Choice of passive voice is affected by verb type and animacy. J Mem Lang 33(6):715–736

Gass SM (1979) Language transfer and universal grammatical relations. Lang Learn 29(2):327–344

Gennari SP, MacDonald MC (2008) Semantic indeterminacy in object relative clauses. J Mem Lang 58(2):161–187

Gennari SP, MacDonald MC (2009) Linking production and comprehension processes: the case of relative clauses. Cognition 111(1):1–23

Gentner D (1981) Some interesting differences between nouns and verbs. Cogn Brain Theory 4(2):161–178

Gibson E (1998) Linguistic complexity: locality of syntactic dependencies. Cognition 68(1):1–76

Gibson E (2013) Processing Chinese relative clauses in context. Lang Cogn Proc 28(1):125–155

Hale J (2001) A probabilistic Earley parser as a psycholinguistic model. In: Proceedings of the Second Meeting of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics on Language Technologies (NAACL ’01), pp 1–8

Homles VM, O’Regan JK (1981) Eye fixation patterns during the reading of relative-clause sentences. J Verbal Learn Verbal Behav 20(4):417–430

Hsiao Y, MacDonald MC (2013) Experience and generalization in a connectionist model of Mandarin Chinese relative clause processing. Front Psychol 4(767):1–19

Izumi S (2003) Processing difficulty in comprehension and production of relative clauses by learners of English as a second language. Lang Learn 53(2):285–323

Keenan EL, Comrie B(1977) Noun phrase accessibility and universal grammar. Linguist Inq 8(1):63–99

Keenan EL, Hawkins S (1987) The psychological validity of the accessibility hierarchy. In: Keenan EL (ed) Universal grammar: fifteen essays. Routledge, London, pp 60–85

King J, Just MA (1991) Individual differences in syntactic processing: the role of working memory. J Mem Lang 30(5):580–602

Kuo K, Vasishth S (2006) Processing relative clauses: evidence from Chinese. University of Potsdam, Potsdam

Levy R (2008) Expectation-based syntactic comprehension. Cognition 106(3):1126–1177

Lewis RL (1996) Interference in short-term memory: the magical number two (or three) in sentence processing. J Psycholinguist Res 25(1):93–115

Li JM, Wang TS (2007) When accessibility meets animacy: Chinese EFL learners’ behavior on English relative clauses. Foreign Lang Teach Res 39(3):198–205

MacDonald M, Christiansen MH (2002) Reassessing working memory: comment on Just and Carpenter (1992) and Waters and Caplan (1996). Psychol Rev 109(1):35–54

Mak WM, Vonk W, Schriefers H (2002) The influence of animacy on relative clause processing. J Mem Lang 47(1):50–68

Mak WM, Vonk W, Schriefers H (2006) Animacy in processing relative clauses: the hikers that rocks crush. J Mem Lang 54(4):466–490

Miller GA, Chomsky N (1963) Finitary models of language users. In: Luce RD, Bush RR, Galanter E (eds) Handbook of mathematical psychology, vol II. Wiley, New York, pp 419–491

Mitchell DC, Cuetos F, Corley MMB et al. (1995) Exposure-based models of human parsing: evidence for the use of coarse-grained (nonlexical) statistical records. J Psycholinguist Res 24(6):469–488

New J, Cosmides L, Tooby J (2007) Category-specific attention for animals reflects ancestral priorities, not expertise. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104(42):16598–16603

Pavesi M (1986) Markedness, discoursal modes, and relative clause formation in a formal and an informal context. Stud Second Lang Acquis 8(1):38–55

Reali F, Christiansen MH (2007) Processing of relative clauses is made easier by frequency of occurrence. J Mem Lang 57(1):1–23

Roland D, Dick F, Elman JL (2007) Frequency of basic English grammatical structures: a corpus analysis. J Mem Lang 57(3):348–379

Traxler MJ, Morris RK, Seely RE (2002) Processing subject and object relative clauses: evidence from eye movements. J Mem Lang 47(1):69–90

Traxler MJ, Williams RS, Blozis SA et al. (2005) Working memory, animacy, and verb class in the processing of relative clauses. J Mem Lang 53(2):204–224

Warren T, Gibson E (1999) The effects of discourse status on intuitive complexity: implications for quantifying distance in a locality-based theory of linguistic complexity. Poster presented at the 12th Annual CUNY Conference on Human Sentence Processing, New York

Wells JB, Christiansen MH, Race DS et al. (2009) Experience and sentence processing: statistical learning and relative clause comprehension. Cogn Psychol 58(2):250–271

Yang CL, Perfetti CA, Liu Y (2010) Sentence integration processes: an ERP study of Chinese sentence comprehension with relative clauses. Brain Lang 112(2):85–100

Yang F, Mo L, Louwerse MM (2013) Effects of local and global context on processing sentences with subject and object relative clauses. J Psycholinguist Res 42(3):227–237

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Humanities and Social Sciences Research Project of Huzhou University (2019XJWK10) and the Scientific Research Funds for Distinguished Scholars, Huzhou University (2018RK20061).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the general committee of the Office of Academic Research at PLA Information Engineering University. The ethical approval required voluntary participation and informed consent. Therefore, the aim and procedures were explained to the participants.

Informed consent

Participation was voluntary. The study did not induce any physical, emotional, or psychological issues in the participants and did not involve any privacy risks or main ethical issues. All participants provided consent, emphasizing the voluntary nature of the participation. Participants were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time, regardless of at which phase they were, without any penalty. They were also informed about the procedures before the tasks. They were aware of what would happen and how the tasks would be done.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, L., Fan, L. & Xu, M. Exploring the effects of animacy and verb type on the processing asymmetry between SRC and ORC among Chinese EFL learners. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 168 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01647-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01647-5

- Springer Nature Limited