Abstract

Following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, the grounds behind Vladimir Putin’s decision were widely debated. Theories suggest several reasons, including Putin’s nostalgic dream of restoring Soviet imperial glory, Russia’s fears of NATO security threats near their borders. But another explanation may be more prosaic: Putin’s desire to restore his sagging popularity at home by attempting to repeat his 2014 “Crimea” strategy. By annexing territories in Eastern Ukraine, he may have hoped to generate a “rally-around-the flag” effect, boosting his domestic support by appealing to Russian patriotism and nationalism. To examine this thesis, Part I outlines the core concept and what is known in the literature about the size and duration of the rally-around-the flag phenomenon. Part II examines the available time-series survey evidence drawn from a variety of opinion polls in Ukraine, Europe, and Russia focusing on the first 8 months of the war to detect any rally effects associated with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Part III examines the evidence of media effects. Part IV adds robustness tests. The conclusion in Part V summarizes the main findings and discusses their broader implications for understanding the roots of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and its consequences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

On February 24, 2022, the Russian Federation escalated war against Ukraine when President Vladimir Putin ordered the “special military operation” to invade across the Northern, Southern and Eastern borders of Ukraine, and launched missiles at Kyiv, Kharkiv, Odessa, and the Donbas. Russia attacked schools, hospitals, and apartment buildings throughout the country, flattening cities, displacing millions of refugees, and killing hundreds—if not thousands—of civilians. These actions, destabilizing peace and prosperity in the heart of Europe, reflected the worst outbreak of inter-state conflict on the continent since 1945. It is therefore important to understand the roots of the invasion, although the reasons behind Putin’s strategic military, economic, and political calculations remain puzzling. Some interpret Putin’s July 2021 speech to mean that aggression has been fuelled by his nostalgic and mystical dreams to resuscitate former imperial glories and restore the world power of the old Soviet empire, unifying of the Russian peoples well beyond the national boundaries of Ukraine (Florea 2022; Kuzio 2022; Putin 2021). Others trace the roots of the current crisis to the 2014 Russian annexation of Ukrainian Crimea, which Mearsheimer argued was provoked by liberal Western delusions about NATO’s enlargement, triggering concern about threats to Russian security on its borders (Mearsheimer 2014).

Alternatively, we theorize that Putin may have decided to invade Ukraine in February 2022 as an attempt to manufacture a “rally-around-the-flag” effect at home, designed to boost his flagging personal popularity among ordinary Russians. By playing the nationalist and patriotic card, he may have hoped to repeat the Crimea strategy he used successfully in 2014, thereby demonstrating overwhelming popular support for his leadership, undermining the expression of dissent by rival opposition forces and pro-democracy movements, and extending his absolute grip on power for years to come. To examine this thesis, we analyze the available time-series survey evidence drawn from a wide variety of opinion polls in Ukraine, Europe, and Russia focusing on the first 8 months of the war to detect any rally effects. Studies in Western societies suggest that with the singular exception of 9/11, any rally effects on leadership popularity ratings are usually modest, at best, and short-lived. But researchers have usually examined survey evidence in the context of open societies and liberal democracies. We theorize that any rally effects on leadership popularity can be expected to prove far stronger and more enduring in closed societies governed by authoritarian regimes with tight control of the media, especially among those habitually exposed to national TV rather than the Internet.

Conceptual and theoretical framework

The “rally-around-the-flag” effect is conceptualized as a rise in approval that state authorities experience at the onset of a major national security crisis, which subsequently decays. Sudden threats to collective national security are believed to generate a patriotic truce and cross-party support for the authorities seen as defending “Us” against risks. In general, social psychological theories suggest that conflict with an “outgroup” is usually believed to increase people’s commitment to their “in-group,” which results in both growing feeling of national identity and greater support for their group leader (Theiler 2018). The early stages of any major threat have often been observed to initially increase public support in the polls for the authorities responsible for managing the crisis, thereby strengthening the popularity of incumbent political leaders, the government, and other official actors and agencies. Such effects have been documented previously, using data comparing “before” and “after” public opinion polls, in response to the events such as the outbreak of inter-state wars like the 1990 Gulf war, a large-scale terrorist attacks like 9/11, and natural or humanitarian disasters, exemplified by the COVID pandemic. Any rally can serve important functions for the authorities; it can expand the capacity to take act decisively in times of crisis, to build a broad bipartisan coalition among elites, and to prevent subsequent security threats (Baker and Oneal 2001). More broadly, mass support for the authorities has long been regarded (rightly or wrongly) as evidence of citizens’ satisfaction with their performance, demonstrating feelings of political legitimacy (Norris 2022).

Several important questions about this phenomenon have commonly been raised in the previous research literature, especially those concerning the typical size of any rating surge and its duration, or how long it usually lasts. Particularly prominent in this respect is the case of the growing popularity of President George W. Bush following the 9/11 terrorist attack. This dramatic event generated one of the largest and most rapid of all recorded rallies in the USA, as the standard presidential approval rating in Gallup polls surged from 51% immediately prior to the attack to a remarkable 90% on September 22, within 12 days. The terrorist attack on America also generated the longest rally in presidential popularity, lasting about 14 months, until November 2002 (Chatagnier 2012). Yet although 9/11 is widely cited, in fact the impact of this event was exceptional; in most cases which have been examined in various Western democracies, both the observed size and the duration of any rally effects on leadership popularity have usually proved moderate (Baum 2002; Hetherington and Nelson 2003; Marra et al. 1990). Most rallies in America can more accurately be described as “short-lived spikes”; on average, comprising some 3–4% approval increase in voting support lasting for a few months, rather than generating substantial and enduring shifts in leadership popularity (Baum and Groeling 2005). Gallup public opinion polls suggest that throughout the twentieth century, improvements in public support for the president following foreign affairs and military actions like the outbreak of foreign wars usually lasted for about ten weeks on average (Hugick and Engle 2003). In the UK, several studies report that the use of force has been associated with public approval of the government’s record, for example, Margaret Thatcher saw a boost in her popularity following the outbreak of war in the Falklands/Malvinas (Morgan and Anderson 1999). In Spain, the first week after the 3/11 Madrid terrorist attack of 2004 saw a 15% increase of confidence in the government and parliament, but public trust returned to the pre-attack levels within 14 months (Dinesen and Jaeger 2013). More recently, a rally effect has also been documented in cross-national surveys where the initial outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in Spring 2020 was linked with a short-term boost in voting support and trust in leaders and governments in many post-industrial societies (Baekgaard et al. 2020).

The size and duration of any effect have been found to vary, however, depending in part on several conditions. The concept of “rally-round-the-flag” was developed in the early 1970s by Mueller who suggested that for an event to cause the rally it must be international in its scope, to confront the nation as a whole; dramatic and sharply focused, to assure public interest; and finally, it should involve the country and its leadership directly (Mueller 1970). Building on this, Murray (2017) argued that a positive rally effect depends on several conditions, including whether the issue raised salient concern in the media and public agenda, whether there was a broad bipartisan consensus about the threat, and whether the country was at war at home or abroad. Both the nature and severity of the crisis may play a role. Attacks against a country’s security, such as from military aggression by foreign powers or by international terrorists, are seen as the primary causes for leadership rallies, producing the largest effects. Actions perceived as defensive may be more likely to generate a rally than those regarded as offensive, although this distinction may be fuzzy in practice (Entman 2004). Another factor to consider is the incumbent’s previous popularity: The lower the leadership rating was before the crisis, the more room there is for a boost (Murray 2017). Finally, the size of the rally effect is likely to differ for various political institutions: National-level bodies (like governments, parliaments, and leaders) typically experience the highest surge (Dinesen and Jaeger 2013).

Conditional roles of regimes, media environments, and media use

One issue which has not been thoroughly examined, however, concerns whether the size and duration of any rally effects differ systematically at societal level between open societies governed by democratic states with plural media environments and closed societies where autocratic regimes rule with tight control of the media, and at individual level by users of state-controlled TV. The heuristic model used in this study is illustrated in Fig. 1, emphasizing the conditional effects of media environments and usage, intervening to shape perceptions of threat events.

Most previous empirical research on rally effects has been mainly limited to analyzing survey evidence derived from trends in monthly public opinion polls conducted in long-established liberal democracies, societies with respect for freedom of expression. In democratic countries, the outset of any military conflict or terrorist attack threatening national security is likely to generate a relatively high degree of elite consensus. Opposition leaders and parties typically temporary lay aside their differences to unite patriotically behind support for the foreign and defense policies of the leaders of their national government against any perceived threats to their country. Where a broad consensus about threats to national security is widely shared among political elites, security forces, the intelligence services, and military experts, as in the case of the attack of 9/11, it has been argued that the domestic media are also likely to reflect this frame in their initial coverage, with journalists relying upon official sources of information (Brody 1991). In this context, the public is exposed to what Zaller called “one-sided” forms of communication (Zaller 1992). Over time, as the initial shock of the security crisis fades, and if the saliency of the threat diminishes, in democracies with competitive party systems and in open societies with media pluralism and freedom of expression, the elite truce is gradually likely to breakdown and normal partisan debate will subsequently resume, including opposition scrutiny of foreign policy decisions in the legislature and journalistic criticism of the government’s management of any crisis.

The opposite to this, in closed societies governed by authoritarian regimes, leaders exert substantial control over the mass media through state ownership and propaganda, official censorship, and repressive restrictions on dissent. In particular, in countries like Russia and China, where autocrats shut down independent media, imprison opposition leaders, and silence public protest, the authorities have considerable control over framing patriotic messages in the mass media rallying nationalist forces, and there are restricted opportunities for the public to be learn accurate information about the negative consequences of the government’s handling of any crisis, like reports of civilian and military causalities. For all these reasons, in closed societies, following the initial onset of any major national security crisis, we predict that (H#1) the size of any rally effect on leadership popularity are likely to be more substantial—and (H#2) their duration will probably persist for longer—than is commonly observed in equivalent open societies and democratic states. Moreover, at individual level, among ordinary citizens living in closed societies, we predict that (H#3) the size and duration of any rally effect will be greater among citizens habitually exposed to news outlets with high levels of government control (such as state TV channels), compared with habitual users of the Internet featuring information from more critical independent sources.

Evidence of rally effects in Ukraine, Europe, and Russia

The inter-state conflict between Russia and Ukraine provides a classic case study which allows us to examine the size and duration of any rally effects. We can compare those observed in surveys conducted in Ukraine, the European Union, and the Russian Federation.

Rally effects in Ukraine

Given the grave existential threats against their citizens, to date the rally effects in Ukraine have been substantial. The invasion has been accompanied by enormous Russian brutality toward the civilian population, sizable destruction of Ukrainian infrastructure and residential buildings which shocked the world, and a massive humanitarian crisis for the millions displaced as refugees within and outside of the country. Given the existential security threat facing everyday life throughout Ukraine, the country saw a particularly sizable and persistent rally effect in leadership popularity. A series of surveys have been conducted across the resident population living in Ukraine (with the exception of the Donbass region and refugees living abroad) by an independent research organization, Sociological Group “Rating” on behalf of the Center for Insights in Survey Research (funded by IRA/USAID) (International Republican Institute 2022). In this series, when asked whether they approved or disapproved of the activities of the President of Ukraine Volodymyr Zelensky, his popularity rating surged from one third (32%) expressing strong or somewhat approval in December 2021, immediately prior to the invasion of the country, to overwhelming popularity in late February 2022, when 93% of Ukrainians expressed approval (Sociological Group Rating 2022). In the June 2022 poll, 91% of Ukrainians continued to approve of his job performance, although the proportion who “approved strongly” did decline from 74% in April 2022 to 59% in June 2022, as conflict continued (International Republican Institute 2022). The poll conducted by the Kyiv Institute of Sociology for the National Democratic Institute on August 2–9, 2022, indicated that the rally effect persists with the approval of President Zelensky remaining at the level of 88% (National Democratic Institute 2022). As the Russia’s war in Ukraine continues, another poll of the Kyiv Institute of Sociology conducted in May of 2023 provides evidence of only slight weakening of the rally effect in Ukraine, when 86% of Ukrainians positively assessed Zelensky as the leader “capable to work effectively as Supreme Commander and organize the defense of the country” (Kyiv Institute of Sociology 2023). In the same vein, the polls by the Info Sapiens research center indicate that the share of those who would have supported Zelensky in the next presidential elections went down only by a few percent points, from 75% in Spring of 2022 to 69% in Winter of 2023 (Info Sapience 2023). This trend data suggests that there was indeed a substantial (60 point) rally effect on leadership approval following the initial Russian armed invasion in Ukraine which has largely persisted in subsequent months, although there is some weakening over time in the most positive endorsements of President Zelensky.

Rally effects in the European Union

Given the far lower (although not negligible) security risks, the size of any effects in Europe is expected to be far weaker. According to Eurobarometer surveys, Putin’s offensive against Ukraine appears to have reinforced slightly greater public support for the EU, as well as for democracy as its core value (Eurobarometer 2022a). In Eurobarometer surveys, from December 2021 to April 2022, the image of the EU grew slightly more positive from 49 to 52%; the image of the European Parliament similarly rose from 36 to 39%; the importance of their country membership in the EU increased more substantially from 61 to 70%; and their positive perceptions of their country’s membership in the EU as a good thing expanded from 62 to 65%, its highest value since 2007 (Eurobarometer 2022a). In line with this, in Summer 2022 the share of those thinking that “things in the EU are going in the right direction” grew by 10 points, from 33 to 43%, and the need for protection of democracy as the core value increased from 32 to 38%. The Eurobarometer survey conducted in April 2022 also indicates a large consensus among EU citizens in all EU Member States in favor of the EU’s response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine (Eurobarometer 2022b). EU citizens also stressed that Europe is standing united (62%) in their response, with many (43%) experiencing an increased sense of European identity and belonging. In the Eurobarometer polls from Winter 2023, however, the positive image of the EU and trust to the EU have decreased by a few percent points and returned to the pre-war level of the Winter of 2021/2022 (Eurobarometer 2023). Available evidence therefore suggests that both the average size of the rally effect across the EU (3–6%) and the duration of this effect have been consistent with the earlier observations made in the literature for this type of phenomenon in democracies and open societies.

Rally effects in Russia

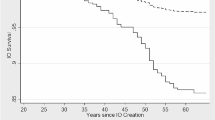

The most reputable series of public opinion data in Russia available comes from the Levada Center, a non-governmental research organization conducting regular surveys since 1988. Approval of Vladimir Putin’s activities, in turn as the Prime Minister and the President of Russia, has been studied by the Levada Center since 1999. Figure 2 illustrates the trends in presidential approval recorded in these surveys. According to the Levada Center polls, Putin’s approval surged 20 points from 63% at the end of 2021, one of the lowest points of his presidency, up to 83% in March 2022 and it remained at this level in August 2022, 6 months after the invasion (Levada Center, 2022a). Moreover, this was not simply a fluke or responses to a single item. Alongside support for the president, other political indicators strengthened consistently as well: Approval of Prime Minister’s activities grew from 54% in December 2021 to 71% in March 2022; approval of the Russian government rose from 49 to 71% over the same period of time. These indicators remain stable after March with the changes within the margin of error. In the Levada poll on Putin’s approval in August 2023, the rating did not change, with 80% expressing approval and just 16% disapproval, similar to those reported since the onset of war. Overall, when asked whether they personally supported the actions of Russian military forces in Ukraine, the proportion of those expressing approval was overwhelming but it dropped very slightly as conflict persisted, from 81% in March 2022 to 73% in June 2023 (Levada Center 2023).

Approval of Vladimir Putin as the President/Prime Minister of Russia (%). Data source: monthly polls by Levada Center (https://www.levada.ru/en/ratings/)

How does the 20-point rally in support for Putin following the invasion of Ukraine compare with longer trends during his tenure in power? According to the Levada polls, as Fig. 2 shows, Putin’s first rating peaked at 84% in January 2000, in a honeymoon period following his ascension to become Russia’s Acting President. In these surveys, Putin’s rating remained quite high (70% to 80%) in his first term as the President, with the patterns indicating some decline to 60–65% in 2005. The period between 2005 and 2008 was associated with the rapid growth of GDP in Russia, as well as the country finally gaining control over Chechnya. Putin’s rating over this period grew to 70–80% reaching its historical maximum of 88% in September of 2008 upon the end of the Russian-Georgian war and the occupation of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Since then, the decline of Putin’s rating occurred slowly but steadily. The level of his approval among the citizens subsided to 60% in late 2013, following a series of anti-authoritarian protests in 2012–2013 which called for greater civil liberties and fair elections, but were traditionally suppressed by the state authorities in the violent manner.

The war in Ukraine is ongoing at the time of writing and thus it would be premature at this stage to make any predictions about the persistence of Putin’s strengthened support or future trends in public opinion toward the conflict. But for an illuminating comparison we can examine the first major case of rallying around the flag in Russia associated with the annexation of the Crimean Peninsula during early 2014. This event caused substantial international resonance and it was followed by the first set of sanctions against Russia imposed by the USA and the EU, thus creating circumstances which confronted the Russian nation as a whole and united it against the “Western enemies” as the common external threat. Hetherington and Nelson (2003) stress that “rally round the flag effect” results in both sudden and substantial surge of the political leader’s ranking. This was exactly the case when approval of Putin surged twenty points, from 65% in January 2014 to 85% in July 2014. With some fluctuations, the Crimea effect lasted for about 4 years, until the summer of 2018, when Putin’s approval fell back to 59% by Spring 2020. Unlike in many European and world countries, the coronavirus pandemic did not appear to trigger any positive “rally” effect for Putin in Russia. The Covid lockdown from March to May 2020 became a challenge for the Russian citizens in economic and social terms, and Putin’s approval rating fell from 69% in February 2020 to 59% in May 2020. His rating went back to the pre-lockdown level in September 2020, after the main measures were lifted.

In addition, public opinion data suggests that in the past, “rally” effects in leadership popularity have been predominantly associated with military interventions, including in Georgia in 2008, Ukraine in 2014 and 2022, and, to a lesser degree, in Syria, as well as Ukraine. From the perspective of today’s Russian–Ukrainian war, are the patterns of the “rally” experienced upon the annexation of Crimea in 2014 likely to be replicated following the war in Ukraine? The cases of military actions in 2014 and 2022 feature some striking similarities—but also differences. Foremost, we can observe that the effect size measured as a surge of public approval for the President comprises about 20 percentage points and it is remarkably similar in size in 2014 and 2022. The causes for the growing support of the president have been quite similar as well. In both 2014 and 2022, the surge occurred after military invasion and occupation (annexation) of territories of another state. What is different in both cases, however, are the number of casualties and costs, both human and economic. The annexation of Crimea started with the Russia-backed demonstrations against the new interim Ukrainian government in late February 2014 and ended with the orchestrated and falsified Crimean referendum on accession to Russia in mid-March, thus resembling the practice of the “Blitzkrieg” and causing a wave of patriotic euphoria. By contrast, the grinding Russian–Ukrainian war of 2022 is anything but that. The Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 has now triggered more than 18 months of violent fighting, with far from any conclusion or any foreseeable outcome. As the brutal fighting continues, and more and more Russian soldiers return home in bodybags, according to the US estimates, by August 2023 Russian military casualties approached almost 300,000, levels far worse than the Soviet-Afghan war of 1979–1989 (Cooper et al 2023). It is becoming increasingly difficult for propaganda to pass the off the war in Ukraine as a victory for Russia. Furthermore, the longer period of the war gives more time for the information flows to evolve; reports about poorly equipped Russian soldiers have spread around the world, further undermining the image of a “strong” Russian army on the brink of victory (Staiano-Daniels 2022).

Media environment and public opinion in Russia

A prominent role in explaining both the size of the rally effect as well as its liveability has been attributed to the role of media (Baum and Groeling 2005). As international crisis often occurs far from home, only a limited share of citizens can evaluate events based on individual experience as immediate participants or witnesses. The vast majority have to rely on information from mass and social media reports, including official announcements by state authorities (or members of the political elite). In this situation, the media have a unique power to influence the mind of the society by presenting a frame. The effect can be particularly important in authoritarian countries such as Russia where the state control of the media has grown for many years under Putin and sharply accelerated since the onset of the Ukrainian war (Dougherty 2015). Figure 3 illustrates long-term trends in government censorship of the legacy news media, social media, and Internet, as well as the media bias and the freedom of expression index, based on V-Dem data (with “0” corresponding to the lowest level of freedoms) (Varieties of Democracy 2021).

Freedom of media and censorship in Russia. Data source: V-Dem dataset V 12.0 (https://www.v-dem.net/)

In these circumstances, the media can become a powerful tool of state ideology by saturating people’s minds with specific messages and dominant frame. The most prominent example of such manipulation in the Russian–Ukrainian war of 2022 is the official ban on the use of term “war” by journalists, in favor of the “special military operation.” In a similar manner, coverage of the events in Ukraine in the Russian media is generously flavored with the fake news narrative of “liberation from fascism,” which is supposed to evoke the association with the victorious experience of the USSR in the World War II, thus legitimating the military aggression of Russia in Ukraine. As an “informational autocracy,” whose legitimacy and dominance are largely based on the manipulation of mass and social communication channels, the Russian state has long adopted sophisticated techniques to intervene surgically and thereby manipulate public opinion. As a result, the Russian authorities have considerable control over the messages in the mass media rallying nationalist forces, and there are restricted opportunities for the public to learn accurate information, or just an alternative account of events (Kizilova and Norris 2022).

One of the consistent patterns detected across the surveys is the association between age, media consumption patterns and support for the regime and the war (Alyukov 2022). Public support for the war, and trust in President Putin, can be broken down by individual-level exposure to different types of news media. The results suggest that Russian approval was highest among users of television news, where journalists often echo official sources of information (Survation 2022). Analysis of the Eurasia Barometer survey, conducted in November 2021, reveals substantial differences in Russian political trust by media consumption patterns; trust to the president, government, and parliament was twice as strong among those whose main source of information comprise state-owned television channels compared with respondents who relied on Internet and social media. Moreover, this is not simply the product of the characteristics of different types of media audiences, such as the younger profile of social media users. In Table 1, after controlling for standard background demographic characteristics, watching TV news was positively linked with Russian trust in Putin, and positive perceptions of Russia’s role in the world. By contrast, using the Internet and social media in Russia produced the reverse pattern, with less trust in Putin and more negative views of Russia’s influence (Table 1).

To summarize, in Russia, a complex and all-encompassing state propaganda machine controls all state media and censors the non-state ones, including the online resources. In this situation, reaching out to sources of information presenting alternative accounts of events becomes extremely challenging for a Russian citizen. Yet there is a possibility that mounting Russian casualties (estimated by US officials as approaching 300,000), abundant criticism of Putin’s war in Ukrainian in Western online media, the effects of economic pressures, and especially widespread exodus and protests by Russians in reaction to the “partial military conscription,” may eventually weaken Putin’s rating.

Reliability and robustness tests

When addressing the available evidence, it is important to consider whether we can trust the survey data as a reliable reflection of public opinion toward political leaders—particularly in authoritarian states where respondents may self-censor critical attitudes toward the regime for fear of retribution by the authorities. The “spiral of silence” theory by Elisabeth Noelle-Neuman (1974) suggested that perceptions of being in the majority or minority in opinions within any group or society affects processes of inter-personal communications, especially the open expression of attitudes and beliefs about deeply polarizing issues. Questions about the veracity of responses by survey participants arise with any sensitive questions where a candid and truthful answers are at odds with perceived social norms, or where other negative consequences may arise, like potential social penalties for the expression of certain extreme political views, attitudes contrary to social norms, or engagement in unorthodox forms of behavior. In this context, preference falsification may occur, where private and public preferences toward a regime may differ, when respondents fail to express their authentic feelings out of fear that their replies may be reported to the official authorities, with sanctions or other punishments applied to government critics (Kuran 1997; Schneider 2017).

State control and censorship over public opinion research have been reinforced during the 2022 Russian–Ukrainian war (Erofeev 2021). Therefore, it is especially important to assess the validity of the Russian population surveys before making final conclusions about the observed patterns and trends. One important cross-check on their reliability comes from other surveys on Putin’s approval conducted regularly by other organizations, including the state-controlled VCIOM and FOM. Replication tests suggest that the more that similar results are recorded from similar or functionally equivalent questions monitored by independent surveys conducted in the same country and time-period, the greater the confidence in the generalizability of the findings. Despite the differences in methodology and sampling, both VCIOM and FOM polls report a similar 20 points surge of Putin’s approval between January and March 2022: from 61 to 79% according to the FOM data (FOM, 2022) and from 66 to 81% according to the VCIOM polling results (VCIOM, 2022). Our own survey projects in Russia, the 2021 Eurasia Barometer and the 2018 World Values Survey (WVS) were last conducted prior to the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. According to this data, trust to President Putin was 61% in November 2021 and trust to the government comprised 53% in January 2017, which is consistent with the Levada polls conducted in the same months.

Beyond the validity of national opinion polls, self-censorship, self-selection, and social desirability bias become particularly sharp issues in public opinion research in Russia. This challenge is likely to increase in 2022 in Russia following the introduction of a new law in March that presumes punishment and up to 15 years of imprisonment for the spread of “fake” information (that is not compliant with the official Kremlin version) about the “special military operation” in Ukraine (Reuters 2022). The new law imposes restrictions not only on citizens what concerns their freedom of expression, but also on public opinion research companies concerning the types of questions that they can ask in their polls and the exact wordings that can be used to avoid persecution. Both Russian and Western social scientists agree that due to this, many polls likely show a biased perception of the war in Ukraine in the Russian society (BBC News Russian Service 2022).

In addition to the potential responses bias, comparative analysis of the opinion polls by Russian researchers suggests that problems may arise from falling response rates, increases in the number of interrupted interviews, and under-representation of young people and Internet users in the final samples (Zvonovskiy 2022). At the same time, analysis shows that such changes constitute only a few percent, with the findings of the Levada Center poll indicating that between September 2020 and May 2022 there are almost no changes in citizens’ readiness to participate in opinion polls (42–43%). Methodological experiment carried out by Levada Center in June 2022, that reinterviewed a panel of respondents first surveyed in 2021, also found out that although trust in the President grew in this panel from 62% in 2021 to 78% in Spring of 2022, the response rate (comprising some 27–30%) remained relatively stable, both over time and among supporters and opponents of Putin (Agapeeva and Volkov 2022).

Conclusions and discussion

To summarize, one strategic reason motivating Putin’s military invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 seems likely to have been an attempt to boost popular support at home for his leadership, replicating the 2014 Crimean “Blitzkrieg” experience. The war was designed to validate President Putin as the “great leader” of Russia and legitimate his way of governance, with a patriotic and nationalist victory boosting his domestic popularity and Russia’s status on the world stage, deterring critics from both outspoken opposition leaders at home as well as international condemnations of Russia’s human rights record. In fact, for Putin, the military invasion of Ukraine of 2022 so far has turned out to be a much less successful enterprise than Crimea, involving substantial human losses and economic costs for both Ukraine and for the Russian Federation. The much broader scope of economic sanctions against Russia, and the coherence of the unified response inside the EU and among NATO countries, suggests unanticipated threats to Russian prosperity and global status.

After the 2014 Crimean annexation, the lengthy duration of the rally effect, which remained in place until 2018, and the substantial 20% surge of president’s approval, was much longer that other “rally” examples observed in Western democracies. Partly this can be explained by the nature of the events that caused it: As previous research shows, wars and military activities abroad generally tend to generate longer rallies as compared to other types of crises (Kuijpers 2019). In this regard, we largely agree with and expand upon Mueller’s early theory of rally effect which suggested that in a situation of an international emergency, the leader of the country becomes a particularly essential figure to overcome the crisis (Mueller 1970). The leader thus embodies national unity and their approval by the public grows following increased feelings of patriotism as a reaction to the external threat. This argument does seem plausible in the Russian case; the annexation of Crimea in 2014, according to the Levana Center poll, led to an increase in the feeling of national pride by 15% points: Share of those being proud about living in Russia in general increased from 70% in 2013 to 86% in 2014 (Levada Center 2022b). Increased feelings of patriotism are likely to generate the sense that leadership elites should put aside everyday conflicts, so that all sides unite in the face of a common threat, thus facilitating a more effective response to national security crises and greater cohesion in society.

On the other hand, partly the polling estimates of genuine support for President Putin may be inflated by systemic response bias. But we argue that the size and duration of the rally effects on presidential popularity observed in Russia are likely to reflect the regime’s capacity to control the media narrative. The Russian state is well known for its lack of tolerance of political opposition, and force is used to suppress dissidents and silence independent media (Guriev and Treisman 2019). During the Russian–Ukrainian war of 2022, the Kremlin resorted to various measures, including timely imprisonment of the opposition leader Alexey Navalny and the introduction of the new law used to legitimize punishment and imprisonment for sharing any information about the Russian army or the war in Ukraine that differs from the official narrative. Overall, indices monitoring freedom of political killings and freedom of peaceful assembly in Russia have both worsened since Putin assumed office in 2000 (Varieties of Democracy 2021). With the critics of the regime and Putin’s foreign military activities being silenced in one or another way, the duration of the “rally” effect in Russia lasted longer than in democratic systems, as no alternative accounts of the events are presented to the public. In the longer term, abundant international criticism of Putin’s war in Ukraine, as well as the effects of economic pressure that will gradually evolve under the extensive sanction packages, may eventually lead to a decline in Putin’s ratings. In the short term, however, as the grinding conflict continues, despite Russia’s loss of its soldiers and military hardware, few domestic or international pressures appear effective.

References

Agapeeva, K, and Volkov, D. 2022. Readiness to participate in surveys: Results of an experiment. Levada Center. June 14. https://www.levada.ru/2022/06/14/gotovnost-uchastvovat-v-oprosah-rezultaty-eksperimenta/. Accessed October 8 2022.

Alyukov, M. 2022. Making Sense of the News in an Authoritarian Regime: Russian Television Viewers’ Reception of the Russia-Ukraine Conflict. Europe-Asia Studies 74 (3): 337–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2021.2016633.

Baekgaard, M., et al. 2020. Rallying Around the Flag in Times of COVID-19: Societal Lockdown and Trust in Democratic Institutions. Journal of Behavioral Public Administration. https://doi.org/10.30636/jbpa.32.172.

Baker, W.D., and J.R. Oneal. 2001. Patriotism or Opinion Leadership?: The Nature and Origins of the “Rally 'Round the Flag” Effect. The Journal of Conflict Resolution 45 (5): 661–687. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002701045005006.

Baum, M.A. 2002. The Constituent Foundations of the Rally-Round-the-Flag Phenomenon. International Studies Quarterly 46 (2): 263–298. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2478.00232.

Baum, M.A., and T. Groeling. 2005. What gets covered? How media coverage of elite debate drives the rally-‘round-the-Flag phenomenon: 1979–1998. In The public domain: presidents and the challenges of public leadership, ed. L.C. Han and D.J. Heith, 49–72. State University of New York Press.

BBC News Russian Service. 2022. Do Russians support the war in Ukraine? Depends how to ask. BBC, March 8. https://www.bbc.com/russian/news-60662712. Accessed October 8 2022.

Brody, R. 1991. Assessing the President: The Media, Elite Opinion, and Public Support. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Chatagnier, J.T. 2012. The effect of trust in government on rallies ‘round the flag. Journal of Peace Research 49 (5): 631–645. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343312440808.

Cooper, H, Gibbons-Neff, T, Schmitt, E, and Barnes, J.E. 2023. Troop Deaths and Injuries in Ukraine War Near 500,000, U.S. Officials Say, August 18. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/18/us/politics/ukraine-russia-war-casualties. Accessed September 8 2023.

Dinesen, P.T., and M.M. Jaeger. 2013. The Effect of Terror on Institutional Trust: New Evidence from the 3/11 Madrid Terrorist Attack. Political Psychology 34 (6): 917–926. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12025.

Dougherty, J. 2015. How the media became one of Putin’s most powerful weapons. The Atlantic, May 29. https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2015/04/how-the-media-became-putins-most-powerful-weapon/391062/. Accessed October 8 2022.

Entman, R. 2004. Projections of Power. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Erofeev, S. 2021. Russia’s polling industry is gravely wrong. Here’s how to change it’. Open Democracy. September 14. https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/odr/russias-polling-industry-is-gravely-wrong-heres-how-to-change-it/. Accessed October 8 2022.

Eurobarometer. 2022a. EP Spring 2022 Survey: Rallying around the European flag—Democracy as anchor point in times of crisis. Eurobarometer 2792/EB041EP, June 1. https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2792. Accessed September 25 2022.

Eurobarometer. 2022b. EU’s response to the war in Ukraine. Eurobarometer 2772/FL506. May 1. https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2772. Accessed September 25 2022.

Eurobarometer. 2023. Standard Eurobarometer Winter 2022–2023. Eurobarometer 2872 / STD98, February 15. https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2872. Accessed September 03 2023.

Florea, C. 2022. Putin’s Perilous Imperial Dream. Foreign Affairs. September 8. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/russian-federation/2022-05-10/putins-perilous-imperial-dream. Accessed October 6 2022.

FOM: Foundation Public Opinion. 2022. Vladimir Putin: work evaluation, attitudes. Foundation Public Opinion. October 7. https://fom.ru/Politika/10946#tab_01. Accessed October 08 2022.

Guriev, S., and D. Treisman. 2019. Informational Autocrats. The Journal of Economic Perspectives 33 (4): 100–127. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.33.4.100.

Inglehart, R., et al. 2022. World Values Survey: All Rounds - Country-Pooled Datafile. Madrid, Spain and Vienna, Austria: JD Systems Institute and WVSA Secretariat. Dataset Version 3.0.0. doi:https://doi.org/10.14281/18241.17

Hetherington, M.J., and M. Nelson. 2003. Anatomy of a Rally Effect: George W. Bush and the War on Terrorism. PS, Political Science & Politics 36 (1): 37–42. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096503001665.

Hugick, L., and Engle, M. (2003). Rally Events and Presidential Approval—An Update. American Association for Public Opinion Research, May 15–18. USA: Nashville, TN.

International Republican Institute. 2022. Public opinion survey of residents of Ukraine: June 2022. International Republican Institute. August 11. https://www.iri.org/resources/public-opinion-survey-of-residents-of-ukraine-june-2022/. Accessed September 25 2022.

Kizilova, K., and P. Norris. 2022. Assessing Russian Public Opinion on the Ukraine War. Russian Analytical Digest 281: 2–5. https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000539633.

Kuijpers, D. 2019. Rally Around All The FLAGS: The Effect of Military Casualties on Incumbent Popularity in Ten Countries 1990–2014. Foreign Policy Analysis 15 (3): 392–412. https://doi.org/10.1093/fpa/orz014.

Kuran, T. 1997. Private Truths, Public Lies: The Social Consequences of Preference Falsification. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Kuzio, T. 2022. Russian Nationalism and the Russian-Ukrainian War. Taylor and Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003191438.

Levada Center. 2022a. Indicators. Levada Center. August 31. https://www.levada.ru/en/ratings/. Accessed September 03 2023.

Levada Center. 2022b. Social Wellbeing Assessment. Levada Center. May 18. https://www.levada.ru/2022/05/18/otsenki-sotsialnogo-samochuvstviya/. Accessed October 8 2022.

Levada Center. 2023. Conflict with Ukraine: Assessment for Late June 2023. Levada Center. July 14. https://www.levada.ru/en/2023/07/14/conflict-with-ukraine-assesments-for-late-june-2023/. Accessed September 03 2023.

Marra, R.F., C.W. Ostrom, and D.M. Simon. 1990. Foreign Policy and Presidential Popularity: Creating Windows of Opportunity in the Perpetual Election. The Journal of Conflict Resolution 34 (4): 588–623. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002790034004002.

Mearsheimer, J. 2014. Why the Ukraine Crisis Is the West’s Fault: The Liberal Delusions That Provoked Putin. Foreign Affairs 93 (5): 77–89.

Morgan, T.C., and C.J. Anderson. 1999. Domestic Support and Diversionary External Conflict in Great Britain, 1950–1992. The Journal of Politics 61 (3): 799–814. https://doi.org/10.2307/2647829.

Mueller, J.E. 1970. Presidential Popularity from Truman to Johnson. The American Political Science Review 64 (1): 18–34. https://doi.org/10.2307/1955610.

Murray, S. 2017. The “Rally-‘Round-the-Flag” Phenomenon and the Diversionary Use of Force. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. New York: Oxford University Press.

National Democratic Institute. 2022. Opportunities and challenges facing Ukraine’s democratic transition. National Democratic Institute. September 19. https://www.ndi.org/publications/opportunities-and-challenges-facing-ukraine-s-democratic-transition-0. Accessed October 06 2022.

Noelle-Neumann, E. 1974. The Spiral of Silence: A Theory of Public Opinion. Journal of Communication 24 (2): 43–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1974.tb00367.x.

Norris, P. 2022. In Praise of Skepticism Trust but Verify. Oxford University Press.

Putin, V. 2021. Article by Vladimir Putin on the historical unity of Russians and Ukrainians. President of Russia, July 12. http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/66181. Accessed October 06 2022.

Reuters. 2022. Russia fights back in Information War with jail warning. Reuters. March 4. https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/russia-introduce-jail-terms-spreading-fake-information-about-army-2022-03-04/. Accessed October 08 2022.

Schneider, I. 2017. Can We Trust Measures of Political Trust? Assessing Measurement Equivalence in Diverse Regime Types. Social Indicators Research 133 (3): 963–984. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-016-1400-8.

Sociological Group Rating. 2022. National poll: Ukraine at war (February 26–27, 2022). Sociological Group Rating, February 27. https://ratinggroup.ua/research/ukraine/obschenacionalnyy_opros_ukraina_v_usloviyah_voyny_26-27_fevralya_2022_goda.html. Accessed October 06 2022.

Kyiv International Institute of Sociology. 2023. All-Ukrainian Public Opinion Poll (May 26 to June 5, 2023). https://kiis.com.ua/?lang=engandcat=reportsandid=1252andt=1andpage=1. Accessed September 03 2023.

Info-Sapiens Research Center. 2023. Changes in the Ukrainian Society Over the First Year of the War (February 23, 2023). https://www.sapiens.com.ua/publications/socpol-research/259/War_Changes_23.02_UKR_.pdf. Accessed September 03 2023.

Staiano-Daniels, L. 2022. The Russian Army is an atrocity factory. Foreign Policy. May 18. https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/05/18/russia-atrocities-ukraine-soldiers/. Accessed October 06 2022.

Survation. 2022. War in Ukraine, the view from Russia. Survation. March 17. https://www.survation.com/war-in-ukraine-the-view-from-russia/. Accessed October 08 2022.

Theiler, T. 2018. The Microfoundations of Diversionary Conflict. Security Studies 27 (2): 318–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/09636412.2017.1386941.

Varieties of Democracy. 2021. V-Dem dataset V12.0. https://www.v-dem.net/. Accessed October 8 2022.

VCIOM: Russia Public Opinion Research Center. 2022. Trust in politicians. https://wciom.com/our-news/ratings/trust-in-politicians. Accessed October 8 2022.

Zaller, J.R. 1992. The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion. New York: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511818691.

Zvonovskiy, V. 2022. Cooperation of respondents in surveys on military operation. Extreme Scan. April 23. https://wapor.org/wp-content/uploads/ExtremeScan-Release-6-2022-04-23_RU.pdf. Accessed October 8 2022.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Vienna.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kizilova, K., Norris, P. “Rally around the flag” effects in the Russian–Ukrainian war. Eur Polit Sci 23, 234–250 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-023-00450-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-023-00450-9