Abstract

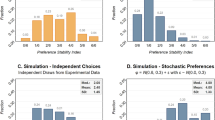

We compare individual risk preferences elicited through a classic Ordered Lottery Selection (OLS) procedure with five gambles, and an extended procedure composed of nine gambles. The research question is about the consistency of the risk preferences across these two elicitation variants. We implemented a field experiment with 1002 rural households in the Congo Basin from December 2013 to July 2014. We show that 1/3 of the sample is extremely risk averse regardless of the procedure. We found inconsistencies in risk preferences elicited across procedures. Indeed, 45.71% are characterized by inconsistency of preferences, either weak (34.53%) or strong (11.18%); 42.81% of the sample exhibits consistent preferences and the remaining 11.48% of the sample - initially risk neutral in the classic procedure - is classified as risk loving in the extended procedure. Undereducation can be seen as the main driver of the strong inconsistency since the incremental change brought about by the attainment of secondary school on the likelihood to remain consistent is ten times greater than the other considered drivers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We assume 2.5 and -2 as class midpoints for extreme ranges in the extended procedure and 2.5 and 0 in the classic one.

The purpose of a common initiative group of interest is to promote the economic and social development of members through the development of income-generating activities and to overcome the constraints faced by individual small-scale farmers (Biénabe and Sautier (2005)).

References

Agrawal, A., B. Cashore, R. Hardin, G. Shepherd, C. Benson, and D. Miller. 2013. Economic contributions of forests. Background paper 1: 1–127.

Anderson, L., and J. Mellor. 2009. Are risk preferences stable? Comparing an experimental measure with a validated survey-based measure. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 39 (2): 137–160.

Arrow, K.J. 1971. Essays in the theory of risk-bearing. Markham Economics Series.

Barseghyan, L., J. Price, and J.C. Teitelbaum. 2011. Are risk preferences stable across contexts ? Evidence from insurance data. American Economic Review 101 (2): 591–631.

Battalio, R., J. Kagel, and K. Jiranyakul. 1990. Testing between alternative models of choice under uncertainty: Some initial results. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 3 (1): 25–50.

Beattie, J., and G. Loomes. 1997. The impact of incentives upon risky choice experiments. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 14: 155–168.

Berg, J., J. Dickhaut, and K. McCabe. 2005. Risk preference instability across institutions: A dilemna. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 201 (11): 4209–4214.

Biénabe, E., and D. Sautier. 2005. The role of small scale producers’ organizations to address market access. Proceedings of the International Seminar, 28 February–1 March 2005. London UK: Westminster.

Binswanger, H.P. 1980. Attitudes toward risk: Experimental measurement in rural India. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 62: 395–407.

Bocquého, G., F. Jacquet, and A. Reynaud. 2014. Expected utility or prospect theory maximisers? Assessing farmers’ risk behaviour from field-experiment data. European Review of Agricultural Economics 41: 135–172.

Bougherara, D., X. Gassmann, L. Piet, and A. Reynaud. 2017. Structural estimation of farmers’ risk and ambiguity preferences: A field experiment. European Review of Agricultural Economics 44 (5): 782–808.

Camerer, C.F., and R. Hogarth. 1999. The effects of financial incentives in experiments: A review and capital-labor-production framework. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 1 (19): 7–42.

Choi, S., R. Fisman, D. Gale, and S. Kariv. 2007. Consistency and heterogeneity of individual behavior under uncertainty. American Economic Review 97 (5): 1921–1938.

Chuang, Y., and L. Schechter. 2015. Stability of experimental and survey measures of risk, time, and social preferences: A review and some new results. Journal of Development Economics 117: 151–170.

Dave, C., C.C. Eckel, C.A. Johnson, and C. Rojas. 2010. Eliciting risk preferences: When is simple better? Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 41 (3): 219–243.

Deck, C., Lee, J., Reyes, J., and Rosen, C. 2008. Measuring risk attitudes controlling for personality traits. Working paper, University of Arkansas.

C. Deck, J. Lee, J. Reyes, and C. Rosen. 2010. Measuring risk aversion on multiple tasks: Can domain specific risk attitudes explain apparently inconsistent behavior? Working paper.

Eckel, C.C., and P.J. Grossman. 2008. Forecasting risk attitudes: An experimental study using actual and forecast gamble choices. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 68 (1): 1–7.

Filippin, A., and P. Crosetto. 2016. A reconsideration of gender differences in risk attitudes. Management Science 62 (11): 3138–3160.

Gneezy, U., and J. Potters. 1997. An experiment on risk taking and evaluation periods. Quarterly Journal of Economics 112: 631–645.

Harrison, G.W., S.J. Humphrey, and A. Verschoor. 2010. Choice under uncertainty: Evidence from Ethiopia, India and Uganda. Economic Journal 120 (543): 80–104.

Holt, C.A., and S.K. Laury. 2002. Risk aversion and incentive effects. The American Economic Review 92 (5): 1644–1655.

Kydland, F.E., and E.C. Prescott. 1982. Time to build and aggregate fluctuations. Econometrica 50: 1345–1370.

Le Cotty, T., E. Maître d’Hotel, R. Soubeyran, and J. Subervie. 2014. Wait and sell: Farmer preferences and grain storage in Burkina Faso. Working Paper LAMETA.

Liu, E. 2013. Time to change what to sow: Risk preferences and technology adoption decisions of cotton farmers in China. Review of Economics and Statistics 95 (4): 1386–1403.

Megevand, C., A. Mosnier, J. Hourticq, K. Sanders, N. Doetinchem, and C. Streck. 2013. Deforestation trends in the Congo Basin: Reconciling economic growth and forest protection. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Ngouhouo Poufoun, J., and P. Delacote. 2016. What drives livelihoods’ strategies in rural areas? Evidence from the Tridom conservation landscape using spatial probit analysis. Technical report, Laboratoire d’Economie Forestière, AgroParisTech-INRA.

Ngouhouo Poufoun, J., J. Abildtrup, D.J. Sonwa, and P. Delacote. 2016. The value of endangered forest elephants to local communities in a transboundary conservation landscape. Ecological Economics 126: 70–86.

Reynaud, A., and S. Couture. 2012. Stability of risk preference measures: Results from a field experiment on French farmers. Theory and Decision 73: 203–221.

Roda, J.M., B. Campbell, G. Kowero, M. Mutamba, M. Clarke, L.A. Gonzales, A. Mapendembe, H. Oka, S. Shackleton, P. Vantomme, et al. 2005. Forest-based livelihoods and poverty reduction: New paths from local to global scales. Selected Book Chapters 17: 75–96.

Schildberg-Horisch, H. 2018. Are risk preferences stable ? Journal of Economic Perspectives 32 (2): 135–154.

Sonwa, D., Y. Bele, O. Somorin, C. Jum, and J. Nkem. 2009. Adaptation for forests and communities in the Congo basin. In ETFRN news/European Tropical Forest Research Network; No. 50. Tropenbos International, Wageningen, NL.

Wik, M., T.A. Kebede, O. Bergland, and S.T. Holden. 2004. On the measurement of risk aversion from experimental data. Applied Economics 36 (21): 2443–2451.

Funding

This work was supported by a Labex ARBRE innovative project ``Risk Aversion, Livelihoods and Ecosystem Services Provisioning and Deforestation in Multifunctional Landscape (RESEL)''. The UMR BETA is supported by a grant overseen by the French National Research Agency (ANR) as part of the ``Investissements d'Avenir'' program (ANR-11-LABX-0002-01, Lab of Excellence ARBRE). The Center for International Forestry Research-Global Comparative Study (CIFOR-GCS) has contributed to the field work with funding provided by the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD), grant no: QZA-12/0882. The Congo Basin Institute (CBI) is a model of partnership in international development between universities, NGOs, and private business developed by The University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) and the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA). The University of Auburn is a collaborative partner. The University of Auburn is a collaborative partner of this work. Thanks to Pr. Dawoei Zhang for the contribution to the total funding for a 2-year post-doctoral position, with funding provided from his one research grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Describing of the questionnaire

The survey is about socioeconomic and ecological analysis of land uses in the Tridom complex. The answers provided are strictly confidential and will be analyzed for the writing of a doctoral thesis. This thesis aims to reflect on a diagram optimal planning that integrates social, economic and also concerns about conservation of biodiversity at the scale of the Tridom landscape.

Please kindly give me some of your precious time to answer the questionnaire. By ensuring the confidentiality of your answers, we thank you in advance for your agreement.

The questionnaire is composed of three parts and 30 pages.

Part 1 is dedicated to the choice determinants of land use and conversion. The first section deals with the socioeconomic characteristics of the household (age, gender, etc.) with 37 questions. The second section is about the autochthony and tribal affiliation (ethnic group, seniority in the village, etc.) with 7 questions. Third section tackles the land ownership and the nature of the land ownership and uses of forest land (non-timber forest product, property right, etc.) with 17 questions. Fourth section questions the conflict, land grabbing, overlapping and superimposition of user rights with 5 questions. Section fifth concerns transportation infrastructure and urbanization (road network, means of transport, etc.) with 4 questions. Section sixth questions the access to some basic services like access to water, electricity, etc. and also deals with housing characteristics. Section seven is interested in the health and education of the household’s members while section eight questions the households about food safety. The last section is large and composed with 45 questions about the multifunctionality of the landscape: cultural value, tradition, conservation, spiritual and genetic value of the forest for people.

Part 2 of the questionnaire is dedicated to the measurement of the parameters of risk aversion.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

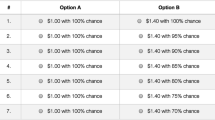

Dear participant, we stop the questionnaire for a short time and we propose to you a little game. More precisely, we propose to you two different tables composed of 5 gambles and 9 gambles, respectively. For each table, you have to choose the gamble that you accept to play for given that each gamble is associated with two payoffs having 50% chance to occur each.

Payoff 1 | Payoff 2 | |

|---|---|---|

Gamble 1 | 4 | 4 |

Gamble 2 | 3 | 6 |

Gamble 3 | 2 | 8 |

Gamble 4 | 1 | 10 |

Gamble 5 | 0 | 12 |

Payoff 1 | Payoff 2 | |

|---|---|---|

Gamble 1 | 100 | 100 |

Gamble 2 | 80 | 128 |

Gamble 3 | 60 | 160 |

Gamble 4 | 40 | 195 |

Gamble 5 | 30 | 215 |

Gamble 6 | 20 | 229 |

Gamble 7 | 18 | 232 |

Gamble 8 | 10 | 234 |

Gamble 9 | 3 | 235 |

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Part 3 of the questionnaire is composed with a choice experiment. In this part, it is indicated that forest provides a significant set of economic, social, and environmental functions and benefits. However, due to its overuse, these functions may disappear in the future if nothing is done. Therefore, government agencies and NGOs consider the implementation of policies that will ensure the future supply of environmental goods and services. These policies may have an influence on people in your area. This study evaluates your preferences for different policies, knowing that they vary according to different attributes such as the biodiversity, the spiritual and cultural resources area, elephant population, forest landscape, and a potential individual compensation. The rest of the choice experiment is classic. Two blocks composed with 9 cards with different combinations of the attributes are proposed to the households.

Appendix 2: Illustrations of the procedure with matchboxes on the ground

Appendix 3: Marginal frequencies and conditional frequencies

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brunette, M., Ngouhouo-Poufoun, J. Are risk preferences consistent across elicitation procedures? A field experiment in Congo basin countries. Geneva Risk Insur Rev 47, 122–140 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1057/s10713-021-00062-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s10713-021-00062-7