Abstract

Partisan polarization in legislators’ roll call voting is well established. In this article, we examine whether partisan and ideological differentiation extends to legislators’ agendas (i.e., the issue content of the bills and resolutions they introduce and cosponsor). Our analyses, focusing on the 101st–110th Congresses, reveal that differentiation occurs both across and within parties (e.g., Democrats and Republicans tend to pursue different issues in their legislative activity, as do moderate and more ideologically extreme copartisans), but that these differences are not typically large in magnitude and did not increase between the late 1980s and late 2000s. These findings suggest that the dynamics of polarization differ for roll call voting and agenda activities in ways that have important implications for our assessments of its consequences. In particular, they highlight that the polarization that has occurred is less a result of differing priorities between Democrats and Republicans and more a function of different preferences on those priority issues. This differentiation may bubble up in part from the true preferences of the rank-and-file, but it is also likely a function of the polarized choices that are presented to them on roll call votes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For a review, see Brian Schaffner, “Party Polarization,” in The Oxford Handbook of the American Congress, ed. Eric Schickler and Frances Lee (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 527–49.

Raymond Bauer, Ithiel de Sola Pool, and Lewis Anthony Dexter, American Business and Public Policy (New York: Atherton Press, 1963); Frank Baumgartner and Bryan Jones, Agendas and Instability in American Politics (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003); Roger Cobb and Charles Elder, Participation in American Politics: The Dynamics of Agenda Building (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1983); Anthony Downs, “Up and Down with Ecology: The Issue Attention Cycle,” The Public Interest 28 (Summer 1972): 38–50; Bryan Jones and Frank Baumgartner, The Politics of Attention: How Government Prioritizes Problems (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005); John Kingdon, Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies (New York: Harper Collins, 1984); E.E. Schattschneider, The Semisovereign People (New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1960).

David Mayhew, Congress: The Electoral Connection (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1974).

See, for example, Barry Burden, Personal Roots of Representation (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007); Richard Hall, Participation in Congress (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996); Gregory Koger, “Position-Taking and Cosponsorship in the U.S. House,” Legislative Studies Quarterly 28 (May 2003): 225–46; Brian Harward and Kenneth Moffett, “The Calculus of Cosponsorship in the U.S. Senate,” Legislative Studies Quarterly 35 (February 2010): 117–43; Michael Rocca and Stacy Gordon, “The Position-Taking Value of Bill Sponsorship in Congress,” Political Research Quarterly 63 (December 2010): 387–37; Wendy Schiller, “Senators as Political Entrepreneurs: Using Bill Sponsorship to Shape Legislative Agendas,” American Journal of Political Science 39 (January 1995): 186–203; Tracy Sulkin, Issue Politics in Congress (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005); Tracy Sulkin, Legislative Legacy of Congressional Campaigns (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011); Gregory Wawro, Legislative Entrepreneurship in the U.S. House of Representatives (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2001).

Burden, Personal Roots of Representation, 9.

These totals are calculated from the data on introductions and cosponsorships described below. In all of the analyses, we focus on bills and joint resolutions. These are functionally equivalent to one another, and, in contrast to other types of measures (e.g., concurrent or simple resolutions) have the force of law if passed.

Abstention is technically an option, but not a feasible one, as MCs are immediately criticized for “missed” votes. Across this time period, the median voting rate for members of the House of Representatives was 97 percent.

For a similar argument about citizens and polarization, see Morris Fiorina, with Samuel Abrams and Jeremy Pope, Culture War? The Myth of a Polarized America, 3rd edn. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson, 2010). Importantly, though, this argument is more likely to hold for citizens than for legislators, since we do have evidence that preferences have changed, and because party leaders can be more pragmatic (and moderate) than their rank and file.

E. Scott Adler and John Wilkerson, Congress and the Politics of Problem Solving (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012); Gabriel Lenz, Follow the Leader? How Voters Respond to Politicians’ Performance and Policies (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012).

Sulkin, Issue Politics in Congress; Sulkin, Legislative Legacy of Congressional Campaigns; Tracy Sulkin and Nathaniel Swigger, “Is There Truth in Advertising? Campaign Ad Images as Signals about Legislative Behavior,” Journal of Politics 70 (January 2008): 232–44.

Frances Lee, Beyond Ideology: Politics, Principles, and Partisanship in the U.S. Senate (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009).

Across this time period, there is a significant difference in the average number of bills introduced in Houses where the Democrats are in the majority (6,499) versus those where the Republicans are (5,441, P=0.05). However, this is due to the substantial drop in introductions when the Republicans first took control in the 104th and the substantial increase when the Democrats regained the majority in the 110th.

John Petrocik, “Issue Ownership in Presidential Elections, with a 1980 Case Study,” American Journal of Political Science 40 (July 1996): 825–50.

See, for example, Noah Kaplan, David Park, and Travis Ridout, “Dialogue in American Political Campaigns? An Examination of Issue Convergence in Candidate Television Advertising,” American Journal of Political Science 50 (July 2006): 724–36; John Sides, “The Origins of Campaign Agendas,” British Journal of Political Science 36 (July 2006): 407–436; John Sides, “The Consequences of Campaign Agendas,” American Politics Research 35 (July 2007): 465–88; Constantine Spiliotes and Lynn Vavreck, “Campaign Advertising: Partisan Convergence or Divergence?” Journal of Politics 64 (January 2002): 249–61.

Stephen Ansolabehere and Shanto Iyengar, “Riding the Wave and Claiming Ownership Over Issues: The Joint Effects of Advertising and News Coverage in Campaigns,” Public Opinion Quarterly 58 (Fall 1994): 335–57.

Sulkin, Legislative Legacy of Congressional Campaigns.

Eduardo Aleman, Ernesto Calvo, Mark Jones, and Noah Kaplan, “Comparing Cosponsorship and Roll Call Ideal Points,” Legislative Studies Quarterly 34 (February 2009): 87–116; Koger, “Position-Taking and Cosponsorship.”

Schaffner, Party Polarization, 529.

See Sulkin, Legislative Legacy of Congressional Campaigns.

To contextualize our results, we compared proportions of introduction attention across the 101st–110th Congresses to that of the previous three decades (the 86th Congress-–00th, 1959–1987). For this earlier period, we relied on Congressional Bills Project categories, so there is not always a perfect match between the schemes. Nonetheless, the figures are largely comparable when comparing issue attention in the later period to the earlier period—crime (5.2 versus 5.8 percent); environment (10.1 versus 11.9 percent); jobs and infrastructure (15.4 versus 16.9 percent); health (7.7 versus 6.2 percent); and defense and foreign policy (14.3 versus 14.3 percent).

The biggest surprise might be defense and foreign policy, where Democrats cosponsor more than Republicans. A large number of bills in this area focus on veterans’ issues, where Democrats are quite active. A similar dynamic may hold across other issue categories (e.g., crime—where some dimensions of the issue are seen as owned by Democrats and others by Republicans), contributing to the small overall differences between the parties.

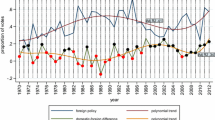

There is an uptick in differentiation in the 110th Congress (2007–2008), and it is possible that this denotes the beginning of an increase. Unfortunately, codes for introductions and cosponsorships in the 111th and 112th Congresses are not yet available.

Schaffner, Party Polarization, 529.

Unfortunately, it is simply not feasible to identify the ideological placement of every introduced measure, and available indicators for the importance of legislation tend to focus on classifying bills and resolutions that reach the floor. It would be interesting to determine whether any patterns are more stark for important legislation, though there is not a strong reason to expect it to be so (though it may be the case that the positions taken in the legislation are more polarized, as these bills are often crafted by committee and party leaders). There is also the complication that “important” legislation that reaches the floor is almost always introduced by a member of the majority party.

Laurel Harbridge, “Is Bipartisanship Dead? Policy Agreement in the Face of Partisan Agenda-Setting in the House of Representatives,” Typescript, Northwestern University. 2014.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

We thank Scott Adler and John Wilkerson (through their Congressional Bills Project) for sharing data, and Kylee Britzman for helpful research assistance.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sulkin, T., Schmitt, C. Partisan Polarization and Legislators’ Agendas. Polity 46, 430–448 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1057/pol.2014.9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/pol.2014.9