Abstract

This paper outlines the UK publishing landscape for the social and political sciences, with particular reference to academic journals. The changes and challenges being brought to this environment by open access (OA) are described and the response of UK publishers examined. While some of the initial caution among publishers towards OA in the social and political sciences is beginning to recede, the pressures of funding, perception and engagement remain considerable. Despite scepticism from some quarters about the future role of so-called ‘legacy’ publishers, it is argued that their skills, knowledge and innovation will make them a valuable part of the evolving, and ever more varied, scholarly communications arena.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

‘Openness’ has been one of the key buzzwords of scholarly communication over the past few years. Open access (OA) – defined as the unfettered access to and re-use of academic research – is just one component of a wider set of ‘open’ developments that also includes open data, open courses and open educational resources. Driven in varying degrees by technological, ideological, ethical, commercial and managerial factors, the movement towards openness has a long history. The physics paper sharing site arXiv first went live in 1991, with the Social Science Research Network – home to the American Political Science Association’s conference papers – coming along just 3 years later. The diversity of open initiatives means that they touch upon a great deal of academic publishers’ output, although it is in their journals divisions where the greatest impact has been felt so far. This paper therefore focuses on OA in a journals context while acknowledging the broader dimensions of the openness debate within academia.

UK SOCIAL SCIENCE PUBLISHING IN CONTEXT

The United Kingdom punches above its weight when it comes to academic social science publishing. Nearly all of the publishers with extensive social science journal portfolios are either headquartered in the United Kingdom (Cambridge University Press, Emerald, Oxford University Press, Palgrave Macmillan, Taylor & Francis) or else have significant bases there (Elsevier, SAGE, Springer, Wiley). Alongside these big hitters are a number of smaller but thriving operations such as The Policy Press and the university presses of Liverpool and Edinburgh, as well as small-scale operations such as The White Horse Press or Imprint Academic. Taken together they form a diverse group, ranging from the corporate giants whose publishing profiles are slanted towards Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) research, to not-for-profits and specialist independents. All of them, regardless of their size or philosophy, work in a global environment with an author base, readership and network of society partners that are truly international. Cambridge University Press, for example, is physically located in nine main hubs on six continents, with several dozen satellite offices dedicated to interactions with specific local markets. While Europe and North America still dominate in terms of research output, the emerging economies, led by China and India, are contributing in ever-increasing amounts. In 2013 Nature reported that the proportion of the world’s research output produced by China rose from 5.6 per cent in 2006 to 13.9 per cent just 5 years later (Van Noorden, 2014).

OA has for the past 3 years been particularly close to the forefront of UK publishers’ minds, thanks in large part to the vanguard actions of British government. The ripples of the June 2012 Finch Committee report (Working group on Expanding Access to Published Research Findings, 2012) were felt around the world, and its recommendation that direct funding be used to drive OA was swiftly translated into practice by the UK Research Councils (RCUK, 2013). The RCUK approach, which favours the up-front payment of article processing charges (APCs) in return for the immediate free availability of the ‘version of record’,Footnote 1 has been subject to criticism for being more suited to funding-rich STEM subjects (see, e.g., Mandler, 2014). More recently, however, the Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE) announced that all submissions to the next Research Excellence Framework must be made OA via the self-archiving of the accepted manuscript.Footnote 2 For moderately funded social science it is the HEFCE policy that is the more significant, and HEFCE hopes that it will greatly increase the proportion of UK research that is openly available from the current estimate of around 12 per cent (see Department of Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS), 2013: 55).

Of course, the RCUK and HEFCE policies are just part of a broader global picture. As of November 2014 the ROARMAP (Registry of Open Access Mandating Policies) lists some 503 OA mandates from funders, governments and institutions worldwide, with a further twenty-eight proposed (http://roarmap.eprints.org/, accessed 18 November 2014). In Europe the EU has introduced OA mandates in relation to its Horizon 2020 funding programme, while in the United States there are no less than three initiatives on the table relating to research funded by the larger federal agencies: a directive from the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) together with two competing acts before Congress.Footnote 3 Most recently, in May 2014, China’s two largest funding bodies announced mandates that affect over 100,000 research papers each year, including some in the social sciences and humanities (Van Noorden, 2014). The vast majority of these mandates operate, as the HEFCE one does, on the basis of ‘green’ self-archiving; it remains to be seen how successfully the UK Government’s ‘gold’-leaning approach can be exported.

Publishers are responding to this evolving legislative environment, which frequently sees co-authors of a journal article subject to multiple mandates with different terms. As research outputs and mandates multiply, they are also working against a backdrop of squeezed library budgets,Footnote 4 increased administrative demands on academics’ time, and the rise of impact agendas. There is too, as is especially evident in the United States, a mood of aggression in some quarters against the funding of social science research, with political science taking the brunt of these attacks.Footnote 5 The combination of these factors is having an effect on all aspects of the academic publishing business, and acts as both accelerator and brake with regards to the development of social science OA journals.

WHAT ARE PUBLISHERS DOING NOW?

The overall number of OA journals in the social sciences may come as something of a surprise: the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ) currently lists over 1,100 titles (http://doaj.org/, accessed 18 November 2014). Of these only around sixty – depending on where you draw the social science boundary – are from what could be considered as ‘traditional’ publishers.Footnote 6 The overwhelming majority are published independently with financial and administrative support from university departments, libraries or other bodies.

‘… the response by UK-based publishers to OA in the social sciences has been one of caution’.

In comparison with the STEM sector, the response by UK-based publishers to OA in the social sciences has been one of caution. This is primarily a reflection of a funding situation that makes the switch to an APC-based model rather more difficult than in areas that are well supported by research cash. There are plentiful examples of highly successful APC-based OA journals in the life sciences; in social science at present there are virtually none.Footnote 7 Money is not the only factor, however. The slow start is also related to the relatively late and low levels of engagement with OA among social scientists – APSA’s 2008 guide Publishing Political Science (Yoder, 2008) devotes fewer than two of more than 250 pages to OA – and to the understandable concerns of many learned societies about the potential damage to revenue streams. There has also been strong opposition from some researchers and societies to models of OA publishing deemed to promote academic inequalities or bad practices (e.g., Kirby and Sabaratnam, 2012). That said, there is undoubtedly a growing awareness of and demand for OA among social scientists, albeit unevenly distributed. Anecdotal evidence suggests that age, institution, discipline and the particular tradition or school in which a researcher is working are among the key factors that may influence an individual’s outlook.Footnote 8

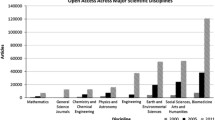

Traditional social science publishers are however starting to shake off some of their initial caution. The pace of change is illustrated by the fact that nearly forty of the sixty or so social science OA journals from the major publishing houses were launched after 2012, with around twenty-five new titles in 2014 alone. These new titles exhibit great variety in terms of funding and editorial models, demonstrating a willingness by publishers to experiment in the OA arena. The majority are based on APC-payment models, with prices ranging from US$195 to $1,360 per article.Footnote 9 However, over a third of the titles rely mainly or entirely on some kind of third-party financial support from sources including universities (from Harvard to Tehran),Footnote 10 private foundations,Footnote 11 learned societiesFootnote 12 and national funding bodies.Footnote 13 There is also diversity in terms of the editorial models employed, with continuous publication ‘megajournals’ like SAGE Open sitting alongside a range of selective, issue-based sub-field titles. Almost every social science discipline is represented by at least one journal from a traditional press, although economics and education are currently the only two fields with clusters of OA publications. Despite this rapid acceleration, the present scale of OA publishing – even when STEM journals are taken into account – is still dwarfed by its subscription counterpart.Footnote 14

‘… there exists at present a disparity between the quantity of OA political science publications and their impact on the field’.

Of course, as the DOAJ figures show, there is a considerable amount and great variety of OA publishing going on outside of the traditional publishing sphere, including almost 300 political science journal titles. The majority of these journals are the initiatives of university departments or local political science associations; most are published in languages other than English. However, there exists at present a disparity between the quantity of OA political science publications and their impact on the field. In the 2013 Thomson-Reuters Journal Citation Reports for political science and international relations there were only three English-language OA journals ranked.Footnote 15 None of these were from the traditional publishing houses, who between them publish just a single journal in the field.Footnote 16 This paucity is mirrored with regards to the presence (or lack of it) of high-profile, scholar-driven projects. Political science currently has nothing to match the likes of Philosophers’ Imprint, Sociological Science or Cultural Anthropology, journals that have been set-up or re-launched on an OA basis expressly independent of links to conventional publishers. Why this should be is unclear, although it should be noted that such projects are often heavily context-dependent upon the coalescence of groups of dedicated, technologically skilled academics who are able to leverage institutional or learned society funding and administrative support.

It should be noted, however, that what political science currently lacks in terms of OA publishing venues it makes up for in terms of its approach to open data. The Data Access and Research Transparency (DA-RT) initiative (see Lupia and Elman, 2014) has galvanized many in the discipline (but by no means all; see, e.g., Isaac, 2015) to place a new emphasis on issues of open data provision, research replicability, and the transparency of data gathering and analysis. The engagement of the DA-RT movement with other disciplines, including psychology, anthropology and sociology may prove to be a highly significant step towards greater openness across the social sciences.

WHERE ARE WE GOING? WHERE DO WE WANT TO GO?

Traditional publishers, especially those whose lists are skewed towards the Humanities and Social Sciences (HSS), are often criticized for being ‘anti-OA’ when displaying levels of caution wholly commensurate to the contemporary scholarly communication environment. What social science needs, and what has become something of a holy grail for all publishers – from the largest corporation to the latest independent OA operation – is the establishment of sustainable, scalable models of OA publishing that fulfil the goals of authors, universities and funders. A successful OA model for the social sciences needs to achieve the goal of accessibility while at the same time allowing for the publication of the highest-quality scholarly work that meets the diverse needs of different disciplinary communities.

Two questions are of central importance to how we might move forward. First, which OA publication models are appropriate for the social sciences? Second, how can these models be developed or transitioned to without causing damage to other parts of the academic ecosystem such as validation, prestige, mentoring and funding? In answer to the first question, there are plenty of off-the-peg STEM examples to draw from, ranging from the high-volume, (relatively) low-APC approach of PLOS ONE to the pay-to-play membership system of PeerJ or the complex subscription substitution arrangements of the SCOAP3 high energy physics initiative. With the increase in levels of experimentation some of these approaches already have HSS analogues, for example, the PLOS ONE-like SAGE Open or the library partnership scheme that will support the Open Library of Humanities.Footnote 17

‘… which OA publication models are appropriate for the social sciences?’

In response to the second question some voices argue that a process of more-or-less controlled disruption to existing academic structures and practices would be a welcome development. In this view the OA question is just one part of a wider set of interlinked issues that also include: the role and value of impact factors; academia’s ability to communicate to external audiences; the fitness for purpose of existing systems of peer review; the ‘precarity’ of early career researchers and the validation of their work; the ongoing suitability of the traditionally conceived ‘journal’ as the vehicle for conveying research findings; the funding and purpose of learned societies; the ability to ‘mine’ text and data easily; the role of profit or surplus in scholarly communication; the relative importance of data transparency and replication; the role of the library in the digital age; and so on. With so many issues and processes entwined, the question of which OA models to adopt relates in part to which issues specific social science communities wish to tackle.

Whatever one’s standpoint on these two questions, the existence of several fundamental features of the academic publishing landscape are generally agreed to be necessary by all participants in the OA debate. Any system of OA scholarly research communication needs to be sustainably supported, both in terms of the provision of editorial operations and the technological infrastructure. In addition it needs to be able to provide some kind of ordering and branding of research work so that the good is sifted from the bad, and so that the really good is given some kind of prominence, delivering of reputation. It should have no or low barriers to entry, so that anyone can submit their research, regardless of their seniority, discipline or funding position. It needs to deliver digital content in a way that libraries and search engines can easily catalogue and make it discoverable to potential readers. And, ideally, it should not add further to the workload burdens that academics already face. There will, undoubtedly, be a variety of ways to achieve these goals, and a wide range of actors engaged in this process as we move towards a more mixed publishing future.

WHAT ROLE FOR PUBLISHERS?

In this evolving environment, what role should traditional publishers play? For some, the answer to that question is ‘none whatsoever’. Such voices tend to arise from two overlapping constituencies: the tech-savvy digital vanguard, and those critical of a scholarly publishing system that they perceive places too much power and resources in the hands of privately owned companies. Internet guru Shirky (2012) encapsulated the first position in his famous remark that in the digital age ‘[publishing] is not a job any more. [It’s] a button’. This quote sums up a view that we live in a post-print world, where the costs of producing and distributing multiple copies of a work are extremely low and where the free availability of open source publishing tools render the ‘legacy’ systems of conventional publishers obsolete. The second position is centred on narratives of power, viewing traditional publishing as an exploitative practice characterized by free labour and high profit, with the ‘fetishisation’ of journal rankings linked to the rise of the bean-counting ‘neoliberal university’ (e.g., Harvie et al, 2012 Monbiot, 2011). Such a view is frequently accompanied by calls for publishing to be ‘taken back’ in house to the universities where it is claimed that it can be handled both more cheaply and more efficiently, as well as being OA. Both viewpoints advocate active and the more-or-less total transformation of the current system, and seek to address many of the issues outlined above that go well beyond the open availability of content. What then, is the case for evolution over revolution?

The answer, in a nutshell, centres around the fact that much of what traditional publishers do is of great value, arguably more so in a post-print world than ever before. Shirky (2012) himself points out that other facets of the traditional publishing process, such as editing and design remain crucial and need to be paid for. The core functions that academic publishing has performed since its infancy – filtration, curation, registration, presentation, discovery, promotion, archiving – are vitally important to academics and therefore central to publishers’ value proposition. It is perfectly true that most, if not all, of these functions can be performed using open source systems by those who choose to go it alone. Yet the volume of research output steadily increases, and these functions are harder to perform in aggregate, at volume and to a high standard. In the social sciences we have recently seen some journals choosing to cancel contracts with traditional publishers in order to go it alone on an OA basis,Footnote 18 but a wholesale ‘taking back’ of academic publishing is likely to be a more costly and complex transition than many of its proponents acknowledge. Not only would universities and time-pressed academics need to add significant publishing and fundraising tasks to existing workloads, but these institutions would also need to coordinate globally in order to grapple with issues of risk and sustainability that have long been shared with, or handled entirely by, specialist publishers.

It is also true that journal editors and peer reviewers, the ones performing much of the filtering work, are almost always academics whose efforts are generally paid for primarily by their institutions rather than by publishers (although it is worth stressing that the financial support from publishers to editorial teams is far from insignificant both in its amount and its impact: many HSS journals would struggle to operate without it). Yet the argument that publishers add little to the results of the labour freely supplied by authors and editors underplays the substantial costs that publishers carry in coordinating and implementing the entire process through which a piece of text that could simply have been posted on the internet becomes a work of scholarship worthy of serious consideration. As librarian Anderson (2014: 172) points out, ‘any model that proposes to do [this] and then give the resulting documents to readers at no charge faces a problem: it will have to get financial support from a source other than the readers’. This brings us to prices.

Universities have, for several decades, been facing what Anderson (2014: 171) describes as a ‘slow-motion crisis’ of constrained budgets and rising – in some cases aggressively rising – journal prices. One could argue, however, that the ongoing ‘serials crisis’ is overwhelmingly of STEM making: the number and cost of journals in the life sciences far outstrip those of the humanities and social sciences. It is somewhat harder to level the accusation of price gouging at large swathes of HSS journal publishing where, on both sides of the Atlantic, university presses continue to play a significant role. This raises the question of whether in the social sciences ‘free’ has become the enemy of the relatively low cost, potentially undermining a workable, sustainable system.Footnote 19 Such a line of thought is not to deny that there are expensive social science journals; it is not a claim that everyone who wants access to social scientific research material can currently do so; nor is it a plea for the current system to be preserved in aspic. It is however a call for the emerging set of OA experiments (from both existing publishers and newcomers) to be closely monitored and analysed before solutions are proclaimed, and for these solutions to work for the majority and not just for a radical fringe. Replacing the drawbacks of the current system with a fresh and potentially thornier set of problems around funding, sustainability and workload would take the shine off the prize of ‘open’.

‘… publishers need to develop new roles in relation to an increasingly OA world…’

There can be no doubt, however, that academic publishing is changing. New STEM entrants such as PLOS, eLife or PeerJ have spearheaded innovations to technologies, processes and business models that are filtering back to traditional publishers. For the latter the challenge is how to fund, develop and integrate OA systems to run alongside the existing print and subscriptions operations, a process that often adds extra costs in the short-medium term. Existing sales and subscriptions systems now need to be reengineered to work in collaboration with OA-dedicated systems for licensing, APC processing and funder identification. New sets of standards need to be created for the cataloguing of OA material in library collections and funder repositories. And external relationships shift from being focused on the librarian-as-gatekeeper to a much more granular set of relationships with funders, repositories and authors. Reflecting this, publishers need to develop new roles in relation to an increasingly OA world, for example, as guides to the emergent and occasionally confusing terminology around licensing, embargo periods and mandates. Yet many legacy services – even the much maligned print – are still highly valued by sections of the academic and librarian community and are not going to go disappear just yet, despite their long-predicted demise.

For publishers, traditional and new, experimentation in terms of models and approaches is central to thriving in this ongoing period of flux, for out of this process will emerge forms of open publishing that will work for the social sciences in the long term. Among the questions that are being addressed through these experiments are: how much should an APC be in social science? Can megajournals work outside STEM disciplines? How can sponsorship funding models be made to work sustainably? Is there a place for post-publication peer review? And should publishing services be disaggregated and handled by a range of specialist providers? For high-quality traditional presses, the challenge is to be actively engaged in this process while maintaining the consistently elevated service standards to authors, editors, partner associations and readers.

What seems most likely is not a sudden, wholesale transformation but a gradual shift to a more varied publishing economy. This shift has already begun in the social sciences, but its full realization may not emerge for many years to come, the product as much as anything of generational adjustments in views towards scholarly practices and technologies. From where we stand it looks as though this mixed market will, in the social sciences, be primarily coloured Green, with increased author-archiving as the main route towards greater openness. Certainly this appears to be the direction of the vast majority of OA mandates worldwide up to now. Of course, green OA implies that the subscription journals that underpin that model will be around for some time to come – indeed for some areas of HSS low-cost subscriptions may continue to be the most effective way of funding scholarly communication well into the future.

Yet around the fringes, and in increasing quantities, we will also see more APC-based publishing (at lower price points) as well as the development of new business models, such as university library partnerships and journal membership schemes. At the same time grassroots OA publishing in the social sciences will continue to grow, with some emerging titles developing the means to sustain their operations and rival the established order. Alongside this proliferation of OA models the next few years we are also likely to see a parallel diversification of the types of products that fall under the umbrella of ‘journal’, with short-form rapid publication formats, continuous publication megajournals and data journals developing alongside orthodox titles. There will be new national or regional initiatives building on rising levels of research output around the world and the success of initiatives such as Latin America’s SciELO (see http://www.scielo.br/). And there will be increasing collaborations between new entrants and established brands facilitating the exchange of ideas, technologies and infrastructures.Footnote 20

Where OA in the social sciences is concerned, William Gibson’s favourite aphorism seems about right: ‘the future is already here – it’s just not very evenly distributed’ (or, one might add, funded). Achieving a completely even distribution of ‘open’ across all subject areas may be a long-term goal, but UK social science publishers will be among the diverse range of actors whose close collaboration will create the smoothest possible transitional path.

Notes

The ‘version of record’ refers to the final published version of the article, complete with all copyediting corrections and pagination.

The so-called ‘green’ route (as opposed to ‘gold’ OA which refers to the immediate open availability of the version of record) (see HEFCE, 2014).

These two acts are: Fair Access to Science and Technology; and Frontiers, Innovation, Research Science and Technology.

The Association of Research Libraries has reported that the percentage of university funds spent on libraries has shrunk from 3.7 per cent in 1984 to 1.8 per cent in 2011 (http://www.libqual.org/documents/admin/EG_2.pdf).

For coverage, see http://community.apsanet.org/Advocacy/home/.

Here used to mean journal publishers whose primary business model has been, and for the time being continues to be, some form of toll-access to content. This is in contrast to publishers like Public Library of Science or Hindawi that only operate on an OA model.

Success here being defined as financial sustainability and citation metric performance; it is perfectly possible to argue that some APC-based social science journals have been highly successful on other criteria, such as rates of submission, publication and usage. The majority of such journals are too young to make any concrete assessment at this stage.

In this author’s experience, in the social sciences those most committed to the idea of OA tend to be early career researchers working in the critical tradition. Some disciplines also appear to be more actively engaged in these issues, for example, anthropology and sociology. There are, of course, a plentiful number of exceptions to these general observations.

SAGE Open is currently the cheapest at $195 per article; the Brill journals Fascism and African Diaspora currently advertise APCs of $1,350. Of those APC-model social science journals from traditional publishers the most common fee is in the range £500–£750 per paper. Many journals offer discounts or complete fee waivers during their first year or two of operation; almost all continue to offer waivers to authors from low-income nations even after this initial period has ended. Several offer discounted APCs to members of associated learned societies.

See, Journal of Law and the Biosciences http://jlb.oxfordjournals.org/ at Harvard University; Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research http://www.journal-jger.com/ at the University of Tehran.

For example, Journal of Legal Analysis, funded by the Considine Family Foundation http://jla.oxfordjournals.org/.

Social science learned societies that have launched or are considering the launch of OA journals include the American Sociological Association, the Society for the Social Studies of Science, the American Educational Research Association, the Regional Studies Association and the Royal Geographical Society.

For example, African Diaspora, part-funded by The Netherlands Organization of Scientific Research (http://booksandjournals.brillonline.com/content/journals/18725465).

Estimates of OA as a proportion of total scholarly publishing range from 2.5 per cent (gold and hybrid models) to 20 per cent (gold and green combined) (see Anderson, 2014).

These are: Ethics and Global Politics, which is published with the support of the Swedish Research Council and Uppsala University; International Journal of Conflict and Violence, backed by the Ministry of Innovation, Science and Research North Rhine-Westphalia; and Journal of Australian Political Economy, supported by the Australian Political Economy Movement and the University of Sydney. Of these, only Ethics and Global Politics allows for free reuse rights via a CC-BY [Creative Commons Attribution.] licence.

Just one title specialises in political science: Research & Politics, which was launched by SAGE in April 2014 (http://www.uk.sagepub.com/researchandpolitics/). Other interdisciplinary OA titles such as Palgrave Communications, Brill Open Social Science and SAGE Open do publish political science among other subject areas.

Open Library of Humanities is an interdisciplinary OA publishing platform that is set to launch in 2015. Discussion of their ‘library partnership subsidies’ model can be found at https://www.openlibhums.org/2014/04/07/library-partnership-subsidies-lps/.

See, for example, Cultural Anthropology or IDS Bulletin, both of which decided to move from Wiley to pursue independently run and funded OA operations.

For counter-arguments to this position, see Eve (2014a) and Eve (2014b).

For example, the recent linkages between Elsevier and Mendeley, Palgrave Macmillan and Figshare, and SAGE and PeerJ.

References

Anderson, R. (2014) ‘Is rational discussion of open access possible?’ UKSG Insights 27 (2): 171–180.

BIS [Department of Business, Innovation and Skills]. (2013) ‘International comparative performance of the UK research base – 2013’, p. 55, available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/263729/bis-13-1297-international-comparative-performance-of-the-UK-research-base-2013.pdf, accessed 18 November 2014.

Eve, M. (2014a) ‘All that glisters: investigating funding mechanisms for gold open access in the humanities disciplines’, Journal of Librarianship and Scholarly Communication 2 (3): 1–13.

Eve, M. (2014b) ‘We’re a small learned society charging £25. What Are We Doing Wrong?’, 2 November, Dr Martin Paul Eve blog, available at: https://www.martineve.com/2014/11/02/were-a-small-learned-society-charging-25-what-are-we-doing-wrong-oa-for-small-society-journals/, accessed 18 November 2014.

Harvie, D., Lightfoot, G., Lilley, S. and Weir, K. (2012) ‘What are we to do with feral publishers?’ Organization 19 (6): 905–914.

HEFCE. (2014) ‘Policy for open access in the post-2014 research excellence framework’, available at: http://www.hefce.ac.uk/media/hefce/content/pubs/2014/201407/HEFCE2014_07.pdf, accessed 18 November.

Isaac, J. (2015) ‘For a more public political science’, Perspectives on Politics 13 (2): 269–283.

Kirby, P. and Sabaratnam, M. (2012) ‘Open Access: HEFCE, REF2020 and the threat to academic freedom’, ‘Disorder of Things’ blog, available at: http://thedisorderofthings.com/2012/12/04/open-access-hefce-ref2020-and-the-threat-to-academic-freedom/, accessed 18 November 2014.

Lupia, A. and Elman, C. (2014) ‘Openness in political science: Data access and research transparency – introduction’, PS: Political Science & Politics 47 (1): 19–42.

Mandler, P. (2014) ‘Open access: a perspective from the humanities’, UKSG Insights 27 (2): 166–170.

Monbiot, G. (2011) ‘Academic publishers make Murdoch look like a socialist’, The Guardian 29 August, available at: http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2011/aug/29/academic-publishers-murdoch-socialist, accessed 18 November.

RCUK [Research Council United Kingdom]. (2013) ‘RCUK Policy on Open Access’, updated May, available at: http://www.rcuk.ac.uk/RCUK-prod/assets/documents/documents/RCUKOpenAccessPolicy.pdf, accessed 18 November.

Shirky, C. (2012) ‘How we will read’, an interview with Clay Shirky, Findings blog, 5 April, available at: http://blog.findings.com/post/20527246081/how-we-will-read-clay-shirky, accessed 18 November.

Van Noorden, R. (2014) ‘Chinese agencies announce open access policies’, Nature News blog, 19 May, available at: http://www.nature.com/news/chinese-agencies-announce-open-access-policies-1.15255, accessed 18 November 2014.

Working group on Expanding Access to Published Research Findings. (2012) ‘Accessibility, sustainability, excellence: How to expand access to research publications’, June, available at: http://www.researchinfonet.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/Finch-Group-report-FINAL-VERSION.pdf, accessed 18 November.

Yoder, S. (ed.) (2008) Publishing Political Science: The APSA Guide to Writing and Publishing, Washington DC: American Political Science Association.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

The online version of this article is available Open Access

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

mainwaring, d. open access and UK social and political science publishing. Eur Polit Sci 15, 158–167 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1057/eps.2015.83

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/eps.2015.83