Abstract

This Symposium brings together the academic and publishing industry in two key countries (the UK and the US) to analyse and assess the implications of Open Access (OA) journal publishing in the social and political sciences, as well as its different formats and developments to date. With articles by three academics (all involved in academic associations) and three publishers, the Symposium represents an exchange of views that help each of the two sectors understand better the perspectives of the other. More generally, the Symposium aims to raise the visibility of OA among the academic community whose general awareness and knowledge of OA – compared with publishers – has been rather limited to date.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

While the intellectual aim of this Symposium is to assess the implications of Open Access (OA) in the social and political sciences, its authors are also conscious of a simpler goal: to raise visibility and awareness of the issue, especially among the academic community. The Symposium began as a panel organized by the European Consortium of Political Research (ECPR) at the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association (APSA) in Washington DC, 28–31 August 2014. The panel produced some interesting papers and a lively discussion, although the audience was dominated by publishers and librarians, with few academics present. This feature also characterized the earlier search for paper-givers, which is not usually problematic for ECPR panels.

On the one hand, publishers were genuinely enthusiastic about participating and taking forward the debate. Academics, on the other hand, were hard to come by, pleading prior commitments or ignorance of the subject matter. This was particularly so for most countries beyond the UK and US, where the impression one gets is that OA is viewed as a ship on a distant horizon (whose direction is unclear) – far enough away not to trouble academics navigating their own passages. To be fair, this is not their ‘trade’, so maybe this is to be expected. Yet, seen from the perspective of political scientists’ interests in other professional matters (e.g., research assessment, journal impact factors, research funding, teaching methods) and their willingness to write about them (e.g., in the pages of EPS), the coyness about discussing OA might be seen to be surprising, especially in view of the sheer growth that OA has undergone across all the disciplines and the potential impact of OA on academics’ careers.

‘… the impression one gets is that OA is viewed as a ship on a distant horizon (whose direction is unclear) …’

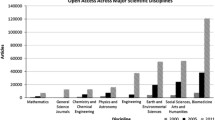

An analysis of the growth in number of OA journals between 1993 and 2009 (Laakso et al, 2011) concluded that, ‘The results speak for the sustainability of OA as a form of scientific publishing, with a large portion of pioneer journals still active and the average number of articles per journal and year almost doubled. It can also be concluded that the relative volume of OA published peer reviewed research articles has grown at a much faster rate than the increases in total annual volume of all peer reviewed research articles. Within the last few years some high-volume and high-impact journals have made the switch to OA which further increases the relative share of openly published research’. In 2011, there were an estimated 6,713 full and immediate OA journals publishing 340,000 articles, with 49 per cent of all articles having been subject to an Article Processing Charge (APC) – a charge on the author in advance of publication (the exact nature of this charge varying across journals). The rate of growth in OA articles subject to APCs has surpassed that of the growth in OA articles not subject to APCs, in a broader context of a decline, between 2010 and 2011 (following years of sustained annual growth) in the number of articles published through subscription-based journals. OA’s relative share of all scholarly journal articles has increased by about 1 per cent annually, with approximately 17 per cent of all articles (totalling about 1.66 million) indexed in Scopus (the largest index of scholarly articles) being available in OA format in 2011, 12 per cent of articles immediately and 5 per cent within 12 months of publication (Laakso and Björk, 2012: esp. Fig 2). This growth is across all disciplinary areas albeit with differences. Journals in the Social Sciences, Arts and Humanities have experienced growth, which is stronger than all other disciplinary areas save Biomedicine (ibid.,: Fig. 5). In political science today there are now over 200 OA journals according to the Directory of Open Access Journals (with the US the leading country for the number of journals hosted) and over 24,000 OA articles (www.doaj.org).

The Registry of Open Access Repository Mandates and Policies, an international registry charting the growth of OA mandates and policies adopted by universities, research institutions and research funders, shows an increase from a total of 158 in 2005 to 727 in 2015 (http://roarmap.eprints.org). There is evident growth in income being generated from OA publishing (see, for example, Ricci and Kreisman (2013: esp. Fig 4), and it is also clear that OA is beginning to have an impact on traditional publishing models in the social sciences and humanities (Worlock and Erickson, 2015).

These are only some of the indicators of the growth of OA from the perspective of journals,Footnote 1 which lie behind Laakso and Björk’s (2012) conclusion that ‘OA journal publishing is disrupting the dominant subscription-based model of scientific publishing …’. In the UK the growth has been accompanied and facilitated by government regulatory action, which is having a direct impact on the activities of academics. In 2013, the UK’s Higher Education Agency made eligibility of academic work for inclusion in the next research assessment exercise (the 2020 Research Excellence Framework) dependent upon that work having appeared in OA format at the point of acceptance. At the same time, the UK’s Research Councils (RCUK) made it mandatory for any published work emanating from an RCUK research grant to appear in OA format. In short, British academics, and universities (as well as publishers), need to be aware of these mandates and what they entail in terms of ensuring that the mode of dissemination of their research meets the criteria. Yet, even in the UK, awareness of and knowledge about OA among academics remains patchy.

This Symposium therefore attempts to inform, analyse and discuss OA in such a way that it raises visibility among the academic and other communities – and it does so for free. The Symposium is published under the Gold Open Access format, and our thanks go to Palgrave for agreeing to waive its standard APCs in order to make this possible. ‘Gold’ Open Access means that there is immediate access to a journal article without charge, usually with rights to re-use its content, which are reasonably liberal (for example the Creative Commons attribution license – CC BY, http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). The costs of production of a journal article are usually met upfront through an APC, since the journals in which Gold OA articles appear do not charge subscription fees. This contrasts with ‘Green’ Open Access, which refers to free access to what is usually an author’s pre-publication final version of an article, via an online institutional or personal repository, with access being possibly subject to an embargo period depending on the publisher’s policy, the article usually being published in a subscription-based journal. There is no APC and re-use rights are usually more restrictive.

The Symposium brings together two sectors (publishers and academics) from two countries (the US and UK). Choosing the US and UK has advantages of coherence insofar as it covers primarily English-language publishing, with a high degree of cross-over in publishers with an international reach. The UK is one of the leaders in the OA field from the perspective of governmental intervention, and the sheer size and importance of the US means that OA developments in that country are more likely to have an effect elsewhere.

The choice of publishers and academics as the sectors of analysis (and authors) of the Symposium may appear to be self-evident, but it should be emphasized that there are other sectors with a stake in OA, which could also have been included, for example, librarians (who have been an influential force behind the growth of OA) and government (or Higher Education agencies) whose regulatory role is and will be crucial to how OA is allowed to develop across different countries. Yet, their contributions may be for another day or venue. Since the readership here is primarily academic, and since an academic’s main partner in disseminating his/her work is the publisher, we thought it would be useful to give a voice to these two sectors as a form of enlightened exchange – but mainly, perhaps, to help social and political scientists understand better their publishers’ perspectives on OA.

‘Forms of OA have long pre-dated government intervention, and the publishing sector has been instrumental in developing them.’

Academics with little knowledge of OA might find it confusing that the publishing sector, which has often been lambasted by (academic) OA purists for its apparent ‘greed’ in milking the subscription model of publishing, and which appears financially to stand to lose most from a transition to OA, is among the strongest proponents of its development, and is in the vanguard of its implementation, often against (academic) resistance to the endangering of rigorous forms of copyright protection. Cynics might argue that this is enforced adjustment to an emerging new reality, that the publishing industry has taken control of OA in order to ensure that implementation can be on its terms, and that, as a consequence, we have witnessed the transformation of what is a fairly simple concept – ‘Open access (OA) literature is digital, online, free of charge, and free of most copyright and licensing restrictions’ (Suber, 2012: 4) – into a complex array of different levels of access, permissions and copyright licenses. Yet, this would be too simplistic a charge to make. Forms of OA have long pre-dated government intervention, and the publishing sector has been instrumental in developing them. Today, as the contributions by Mainwaring (2016) and Hrynaszkiewicz (2016) make clear, publishers are genuinely innovating in developing OA models of publishing in a rapidly changing market. Furthermore, all three of the publishers’ contributions here suggest an awareness that, even though OA forms of publication still represent a small percentage of the overall market, we are in a process of transition, the goal of which is to secure, in Holzman’s (2016) words, ‘a healthy, sustainable scholarly communications ecosystem’. In short, publishers are doing what any successful industry does in developing new products and models of financing. Are political scientists with them?

A short answer might be that they do not care, as long as their work gets published where they would like to publish it, cost-free. The long answer is that there is a certain irony in some of the debates and discussions in the academic sector on OA. On the one hand, there is concern about, if not opposition to, the impact that OA will have on an industry, which has become increasingly structured around the academy’s (or maybe government’s) apparent need to be able to evaluate ‘objectively’ the quality of what it produces. The academic production line has become increasingly ‘bashed into shape’ to the point that academic performance is now measured by instruments of assessment, which are external to the academy itself, involving impact factors and citation indices. This has created a ‘structured environment’ in which academics compete to publish in the highest-ranked (mostly subscription-based) journals. The development of OA, the profusion of new journals and their APC business models and the implications (for copyright and permissions) of shifting to OA licenses, are creating confusion and uncertainty. On the other hand, even leaving aside those who fervently support OA as a crusade, the actions of many academics in promoting their research through the use of online repositories is – whether or not they are aware of it – helping to fuel the further development of OA. Indeed, while university repositories are regulated by trained librarians whose job it is to know what publications can be made publicly accessible and when, other repositories leave responsibility with authors themselves, meaning that copyright and permissions may, in some instances, be (unwittingly) breached. In short, despite concerns – and at times because of ignorance – about OA in the academic sector, its continued growth and consolidation appears inevitable.

The academics selected to contribute to this Symposium were chosen to present different perspectives, as shaped by the different stages of development of OA in the two countries. The impact of the British government’s recent decisions on the OA debate is shown clearly by Carver (2016) even if, as he argues, the impact on the academy and publishing industry may not be as extensive as originally thought. Yet, he also provides a feel for the uncertainty surrounding the whole issue, something one also finds in the American case. If the largest political science association in the world, the American Political Science Association (APSA) is undecided about its positioning on OA, deferring the matter to a committee ‘to be named later’, then it surely signals something about the phenomenon’s complexity and potential impact. As Hochschild (2016) argues, the issues go beyond the benefits and costs to touch on some of ‘the deeper, even moral, conundrums of redistribution and democratic control that might be associated with a move toward a broad programme of gold open access’.

APSA’s uncertainty, however, is also a reflection of the specific implications of OA for academic associations or scholarly societies. The three academic contributors to this Symposium were also chosen because they all have experience of working in academic associations, which provides them with additional insights into the OA debate and an awareness of the issues. Academic associations are the lifeblood of the political science discipline insofar as they facilitate the interaction and collaboration between political scientists so essential to the development of new research, they create and own outlets for the publication of new knowledge in the form of journals, which they produce in collaboration with publishers, and they therefore help researchers to publicise and disseminate their research. Nothing could be more in line with this goal than the development of OA. Yet, at the same time, a significant part of their consolidation and growth has been based on the income generated by the subscriptions to those journals, thus creating a dilemma: that too rapid a transition to OA would undercut their established income base, if not threaten their survival. There is therefore a level of uncertainty and reticence among many associations, all potentially facing difficult transitions. Bull (2016) summarises these dilemmas and identifies possible strategic choices facing academic associations in their quest not just to survive but to offer the same level of services to their academic communities as they do currently.

If one were to draw a broad comparison between the approach of the two sectors to OA, one could say that while the academic sector tends to view the development in terms of a kind of watershed period – one strongly welcomed by some, resisted by others and recognized as needing cautious management by others – the publishing industry, which probably has more to lose, is taking the development in its stride, partly because (unbeknown to many social and political scientists) it has figured in their armoury for some time, and it is thus a matter of extending different forms of OA to new disciplinary areas. The long-term implications of this development, of course, remain unclear, especially for subscription-based journals. Yet, it is important to focus on what should be the overriding goals, which are not about protecting the existing structure, but rather facilitating the production of social science research (Suber, 2012: 161) and its dissemination, and therefore increasing its relevance to the wider world in terms of its utilisation. Morrison (2014) reminds us not to lose sight of the vision expressed in the Budapest Open Access initiative over a decade ago:

An old tradition and a new technology have converged to make possible an unprecedented public good. The old tradition is the willingness of scientists and scholars to publish the fruits of their research in scholarly journals without payment, for the sake of inquiry and knowledge. The new technology is the internet. The public good they make possible is the world-wide electronic distribution of the peer-reviewed journal literature and completely free and unrestricted access to it by all scientists, scholars, teachers, students, and other curious minds. Removing access barriers to this literature will accelerate research, enrich education, share the learning of the rich with the poor and the poor with the rich, make this literature as useful as it can be, and lay the foundation for uniting humanity in a common intellectual conversation and quest for knowledge. (Budapest Open Access, 2002)

That is the challenge facing both the publishing and academic sectors today, and if this Symposium helps raise the visibility and comprehension of this challenge in the social and political sciences it will have served its purpose.

Notes

For further data see Morrison (2014–03) and Morrison (2014), the latter a rolling quarterly analysis of open access data updates.

References

Bull, M.J. (2016) ‘Open access and academic associations in the political and social sciences: Threat or opportunity?’ European Political Science doi:10.1057/eps.2015.88.

Budapest Open Access Initiative. (2002) http://www.budapestopenaccessinitiative.org/read.

Carver, T. (2016) ‘Open access: Nothing much new (or very little, anyway)’, European Political Science. doi:10.1057/eps.2015.86.

Hochschild, J. (2016) ‘Redistributive implications of open access’, European Political Science. doi:10.1057/eps.2015.84.

Holzman, A. (2016) ‘US open access publishing for the humanities and social sciences’, European Political Science doi:10.1057/eps.2015.85.

Hrynaszkiewicz, I. (2016) ‘Open access journals: A sustainable and scalable solution in social and political sciences’, European Political Science. doi:10.1057/eps.2015.87.

Laakso, M. and Björk, B.-C. (2012) ‘Anatomy of open access publishing: A study of longitudinal development and internal structure’, BMC Medicine 10: 124 doi:10.1186/1741-7015-10-124.

Laakso, M., Welling, P., Bukvova, H., Nyman, L., Björk, B.-C. and Hedlund, T. (2011) The development of open access journal publishing from 1993 to 2009, PLOS ONE, 13 June, http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0020961.

Mainwaring, D. (2016) ‘Open access and UK social and political science publishing’, European Political Science. doi:10.1057/eps.2015.83.

Morrison, H. (2014) ‘2014 Dramatic growth of open access: 30 indicators of growth beyond the ordinary’, The Imaginary Journal of Poetic Economics, 31 December, http://poeticeconomics.blogspot.co.uk/2014/12/2014-dramatic-growth-of-open-access-30.html.

Morrison, H. (2014-03) ‘Dramatic growth of open access’, http://hdl.handle.net/10864/10660 Morrison, Heather [Distributor] V9 [Version].

Ricci, L. and Kreisman, R. (2013) ‘Open access: Market size, share, forecast, and trends’, Outsell, 31 January, http://www.outsellinc.com/store/products/1135.

Suber, P. (2012) Open access, Cambridge MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology https://mitpress.mit.edu/sites/default/files/titles/content/9780262517638_Open_Access_PDF_Version.pdf.

Worlock, K. and Erickson, J. (2015) ‘Humanities and social sciences publishing: Market size, share, forecast, and trends’, Outsell, 16 January, http://www.outsellinc.com/store/products/1288.

Acknowledgements

Thanks go to the EPS editors and the other authors of this Symposium for their comments on an earlier version of this Introduction. The views expressed in the article are those of the author and not necessarily of the European Consortium of Political Research (ECPR).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

The online version of this article is available Open Access

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

bull, m. introduction; open access in the social and political sciences: threat or opportunity?. Eur Polit Sci 15, 151–157 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1057/eps.2015.82

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/eps.2015.82