Abstract

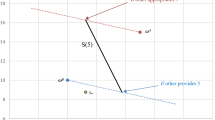

We conduct modified dictator games in which price of giving varies across choice situations, and examine responses to price changes in two contexts—one where dictators divide their own earnings, and another where they divide the earnings of others. Varying the price of giving allows us to decompose social preferences into two components: the level of altruism when the price of giving is one, and the willingness to reduce aggregate payoffs to enhance equity. Changing the source of a dictator’s budget impacts her decisions because it affects the weight that she places on others’ payoffs. However, we find no impacts on the willingness to trade off equity and efficiency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We use a modified version of the experimental design employed by Andreoni and Miller (2002).

For example, Hoffman et al. (1994) and Cherry et al. (2002) find that dictators who earned their positions or their budgets are less generous. Hoffman et al. (1996) find that dictators are less generous in double-blind experiments, while Charness and Gneezy (2008) show that dictators are more generous when they are told other’s last name. List (2007) and Bardsley (2008) find that allowing dictators to either give to or take from other decreases giving. Finally, Lazear et al. (2012) show that some subjects who share a positive amount in dictator games are willing to pay to avoid entering the game, even though their actions are anonymous.

The words “giving” and “taking” were never stated during the experimental sessions.

Sessions 1 and 2 included ten rounds; the remaining six sessions lasted for twelve rounds.

The words “giving” and “taking” were not used during the experiment. The contextual difference derives entirely from the provenance of the dictator’s budget. Hence, in contrast to List (2007), the mathematical structure of the dictator’s constrained optimization problem is identical in the Giving and Taking rounds.

To guarantee anonymity, individual decisions were linked to randomly-generated player identification numbers rather than player names, so even the experimenter could not link choices within the session to specific individuals.

There is no evidence that earners exerted greater effort when the incentive was larger. In fact, increasing the incentive offered by ten tokens is associated with a 2.6 second decrease in the amount of time spent answering a question and a 0.6 percentage point decrease in the probability of a correct response.

The elicitation procedure is similar to that used by Cappelen et al. (2007).

See, for example, Charness and Rabin (2002), though their evidence suggests that positive reciprocity is not a major factor in individual allocation decisions. We might also expect that dictators would feel negative reciprocity toward earners who answer GRE questions incorrectly (Ruffle 1998). Unfortunately, we are unable to explore this using the current experimental design. GRE questions were chosen to be relatively easy, and earners gave the correct response 81 percent of the time. Moreover, since earners were always paid four dollars for incorrect responses, the size of the dictator’s budget in Taking rounds proceeding incorrect responses is perfectly correlated with the price of giving, and the constraint on entering whole numbers of tokens severely limited the dictator’s choice set for prices below one.

All p-values in this paragraph based on t-tests of equality of means across Giving and Taking rounds.

OLS results are similar, and are omitted to save space.

For comparison, a strict egalitarian would spend 25 percent of her budget on other when \(p=\frac{1}{3}\) and 75 percent on other when p=3; thus, the difference would be 50 percentage points.

References

Afriat, S. N. (1967). The construction of utility functions from expenditure data. International Economic Review, 8, 67–77.

Andreoni, J., & Miller, J. (2002). Giving according to GARP: an experimental test of the consistency of preferences for altruism. Econometrica, 70, 737–753.

Andreoni, J., & Vesterlund, L. (2001). Which is the fairer sex? Gender differences in altruism. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116, 293–312.

Bardsley, N. (2008). Dictator game giving: altruism or artefact? Experimental Economics, 11, 122–133.

Bolton, G. E., & Ockenfels, A. (2006). Inequality aversion, efficiency, and maximin preferences in simple distribution experiments: comment. American Economic Review, 96, 1906–1911.

Camerer, C. (2003). Behavioral game theory. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Cappelen, A. W., Hole, A. D., Sørensen, E. O., & Tungodden, B. (2007). The pluralism of fairness ideals: an experimental approach. American Economic Review, 97, 818–827.

Charness, G., & Gneezy, U. (2008). What’s in a name? Anonymity and social distance in dictator and ultimatum games. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 68, 29–35.

Charness, G., & Rabin, M. (2002). Understanding social preferences with simple tests. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117, 817–869.

Cherry, T. L., Frykblom, P., & Shogren, J. F. (2002). Hardnose the dictator. American Economic Review, 92, 1218–1221.

Cox, J. C., Friedman, D., & Gjerstad, S. (2007). A tractable model of reciprocity and fairness. Games and Economic Behavior, 59, 17–45.

Engelmann, D., & Strobel, M. (2004). Inequality aversion, efficiency, and maximin preferences in simple distribution experiments: comment. American Economic Review, 96, 1906–1911.

Fahr, R., & Irlenbusch, B. (2000). Fairness as a constraint on trust in reciprocity: earned property rights in a reciprocal exchange experiment. Economics Letters, 66, 275–282.

Fehr, E., Naef, M., & Schmidt, K. M. (2006). Inequality aversion, efficiency, and maximin preferences in simple distribution experiments: comment. American Economic Review, 96, 1912–1917.

Fischbacher, U. (2007). z-Tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Experimental Economics, 10, 171–178.

Fisman, R., Kariv, S., & Markovits, D. (2007). Individual preferences for giving. American Economic Review, 97, 1858–1876.

Fisman, R., Kariv, S., & Markovits, D. (2009). Exposure to ideology and distributional preferences. Working paper.

Forsythe, R., Horowitz, J., Savin, N. S., & Sefton, M. (1994). Fairness in simple bargaining games. Games and Economic Behavior, 6, 347–369.

Greig, F. (2006). Gender and the social costs of asking: a cost-benefit analysis. Working paper.

Hoffman, E., McCabe, K., Shachat, K., & Smith, V. (1994). Preferences, property rights and anonymity in bargaining games. Games and Economic Behavior, 7, 346–380.

Hoffman, E., McCabe, K., & Smith, V. L. (1996). Social distance and other-regarding behavior in dictator games. American Economic Review, 86, 653–660.

Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J., & Thaler, R. (1986). Fairness and the assumptions of economics. Journal of Business, 59, S285–S300.

Lazear, E., Malmendier, U., & Weber, R. (2012). Sorting in experiments with application to social preferences. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 4, 136–163.

Levitt, S. D., & List, J. A. (2007). What do laboratory experiments measuring social preferences tell us about the real world? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21, 153–174.

List, J. A. (2007). On the interpretation of giving in dictator games. Journal of Political Economy, 115, 482–492.

Ruffle, B. J. (1998). More is better, but fair is fair: tipping in dictator and ultimatum games. Games and Economic Behavior, 23, 247–265.

Varian, H. R. (1982). The nonparametric approach to demand analysis. Econometrica, 50, 945–972.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Stefano DellaVigna, Raymond Fisman, Shachar Kariv, Ulrike Malmendier, Edward Miguel, Matthew Rabin, and participants in seminars at UC Berkeley for helpful comments; and to staff at the Xlab for their help administering the lab sessions. All errors are my own. This research was funded by the Russell Sage Foundation and the UC Berkeley Experimental Social Science Lab (Xlab). The experiment was programmed and conducted with the software z-Tree (Fischbacher 2007).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jakiela, P. Equity vs. efficiency vs. self-interest: on the use of dictator games to measure distributional preferences. Exp Econ 16, 208–221 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-012-9332-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-012-9332-x