Abstract

The use of Polypropylene as support material for nano-TiO2 photocatalyst in the photodegradation of Alizarin Red S in water solutions under the action of visible light was investigated. The optimization of TiO2 pastes preparation using two commercial TiO2, Aeroxide P-25 and Anatase, was performed and a green low-cost dip-coating procedure was developed. Scanning electron microscopy, Atomic Force Microscopy and X-Ray Diffraction analysis were used in order to obtain morphological and structural information of as-prepared TiO2 on support material. Equilibrium and kinetics aspects in the adsorption and successive photodegradation of Alizarin Red S, as reference dye, are described using polypropylene-TiO2 films in the Visible/TiO2/water reactor showing efficient dyes degradation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ground water contamination causes a negative effect on water quality and is likely to be the primary source of human contact with toxic chemicals derived from different sources. Organic dyes, undesirable in water, even in very small amounts, are the first pollutant species to be identified due to their obvious color that is aesthetically unpleasant and it can affect the ecosystems integrity1. Wastewaters generated by the textile industries contain significant amounts of non-fixed dyes and a huge amount of inorganic salts2. For this reasons, degradation and lowering of toxicity of dyes effluents are more important. Because of their complex structure, it’s more difficult to destroy these contaminants which are intentionally chosen to withstand to light and to aerobic oxidation by microorganisms; in fact, only the incomplete degradation of dyes is possible using these processes (physical and microbiological) with the formation of volatile carcinogenic compound as by-product3. The preservation of clean air, soil and water requires the treatment of these dye effluents3. In recent years a great deal of interest to the photocatalytic studies regarding organic water pollutants on semiconductor materials emerged4,5.

The most popular photocatalyst is TiO2 semiconductor for its excellent optical and electronic properties, low price, chemical, thermal and biological resistance, no toxicity, recovery and transparency to visible light6,7,8,9. For these reasons, TiO2 is widely used in many fields such as medical treatment and microorganism disinfection10,11, dye sensitized solar cells6,8,12, self-cleaning materials7,8, purification of water, air and also in the solar water splitting8. The physical features of TiO2 as porosity, morphology, crystallization, surface area and phase transformation influence the photocatalytic activity and the adsorption of the pollutants13. In this contest, also different adsorptive materials including silica, perlite, activated carbon, glass9,14 and others has been tested. The light source plays a primary role in the photocatalytic process due to the fact that the UV or visible irradiation permit different mechanisms. Since TiO2 has a large band gap of 3.0–3.3 eV12, only the photocatalytic process under the action of UV light is possible because TiO2 absorbs a small part of solar spectrum. When TiO2 is irradiated by UV-light with higher energy than its band-gap, the semiconductor is excited and an electron injection occurs from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB) in order to create an electron-hole pair (e−CB, h+VB). The photogenerated holes diffuse to the semiconductor surface and react with adsorbed water molecules in order to generate hydroxyl radicals (•OH) which can oxidize organic molecules on TiO2 surface. Furthermore, the electrons in the conduction band are involved in the reduction process with the air oxygen to produce superoxide radical anions (O2•−) continuing the photodegradation process6,15.

Under visible light, only the adsorbed dye on semiconductor surface is excited and an electron injection into the CB of TiO2 from the excited dye occurs; this one is converted in cationic dye radical whereas the injected electron (e−CB) reacts with the pre-adsorbed oxygen producing several forms of radicals.

The overall process are describe as follows15,16:

In the photocatalytic process, TiO2 can be used in two different ways: immobilized on inert support materials or suspended in aqueous medium. Considering the practical application, immobilized TiO2 is preferable than TiO2 dispersion to avoid the subsequent steps for the recovery of catalyst after the process. The suspended systems give higher degradation rates but the catalysts must be filtered and, as a result, the process is more expensive17. Inert support materials are classified according to their chemical nature; the effects on the semiconductor are the increase of the surface area, change of hydrophobicity, hydrolysis, thermal and chemical stability5.

In this study, two commercial types of TiO2 such as Anatase (A) and Aeroxide P-25 (P-25) were chosen for the preparation of pastes used to cover Polypropylene (PP) strips. New heterogeneous materials were realized for the photodegradation of Alizarin Red S (ARS) as target pollutants under the action of visible light, in different experimental conditions. Crystallographic and morphological aspects of the new material were studied and SEM, AFM and XRD results are presented.

The work proceeds with the adsorption study of dye on TiO2 surface in real time mode and the subsequently photocatalytic degradation process was made in order to obtain equilibrium and kinetic results.

Results

PP@TiO2 Morphology

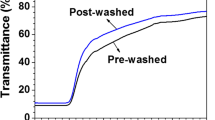

Morphological studies by SEM of [PP@TiO2]P25 before and after acid washing, reported in Fig. 1 show that, the non –regular surface, with the presence of granules excess change to a more regular and uniform layer after this process. From these considerations the acidic treatment is necessary to remove TiO2 surplus on PP surface.

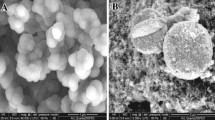

[PP@TiO2]P25 and [PP@TiO2]A surfaces prepared in the same conditions (Fig. 2a,d), at the same magnification, show morphological differences: [PP@TiO2]P25 surface presents very small TiO2 particles with a homogeneous structures with respect to [PP@TiO2]A surface that show instead larger particles of agglomerated nanoparticles.

SEM images of as-prepared [PP@TiO2] strips and their changes during the studied processes.

(a–c) SEM images show the change of morphology on as-prepared [PP@TiO2]P25, after the ARS adsorption and photodegradation. Respectively (d–f) SEM images show the change of morphology of as prepared [PP@TiO2]A, after the dye adsorption and photodegradation respectively.

After ARS adsorption and photodegradation process, changes of PP@TiO2 morphology are observed (Fig. 2b,c,e,f). After the adsorption of ARS, both the samples show not homogenous distribution of the material compared to the same sample in the absence of dye while, after the photo-degradation process was observed a decrease of homogeneity of the TiO2 surface, due to the loss of the absorbed dye.

AFM was used in order to investigate the topography of TiO2 surface, to check the morphological aspects of TiO2 layer by surface roughness analysis by several parameters such as root mean square (Rq), mean roughness (Ra) and width of ondulation (Wmax) as result of the different processes. Figure 3 shows three dimensional surface images for PP@TiO2 films before and after the ARS-adsorption and after the photodegradation step. As well as SEM measurements, AFM images show important differences between [PP@TiO2]P25 and [PP@TiO2]A. All Ra and Wmax values of PP@TiO2 films without dye, with ARS coated and after the photodegradation step are reported in Fig. 3. [PP@TiO2]P25, before the dye adsorption, presents smooth surface and it is supposed that this is due to the presence of regular distribution of the particles as can be seen from the SEM images. On the contrary, [PP@TiO2]A film present a granular structure and a greater undulating surface respect to [PP@TiO2]P25. However, as the roughness is caused by the granular structure, which also provides high surface area, it is supposed that [PP@TiO2]A layers could exhibit higher adsorption capacity compared to [PP@TiO2]P25. After adsorption process, the roughness value of [PP@TiO2]P25 increases considerably due to the dye molecule which cover the smooth surface of [PP@TiO2]P25.

At the same adsorption conditions, from the Ra values of [PP@TiO2]A, it is possible to suppose that dyes molecules fill the space between holes present on TiO2 surface and, as a result, roughness is not modified. The undulating values increase in the adsorption step on [PP@TiO2] surface for both Anatase and Aeroxide P-25; after photodegradation step, the average width of undulating values of [PP@TiO2]P25 and [PP@TiO2]A tends to returns to initial conditions, while an increase of average roughness it has been observed only for [PP@TiO2]A.

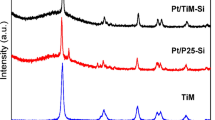

In order to reveal structural variations of the compounds, we also collected some powder x-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns before and after the adsorption process.

Figure 4 shows the XRD patterns of TiO2 Anatase (left side) and Aeroxide P-25 (right side). In this figure the black line (A) and the red line (B) are referred respectively to the data collected before and after the adsorption process, while are also visible the calculated patterns for Anatase (blue) and Rutile (magenta) structure phases (C).

In Fig. 5 we present a magnification of our XRD data in the range 10–32 deg in order to better analyze the main diffraction peaks.

The analysis of the [PP@TiO2]A pattern reveals that the structure of TiO2 (Anatase) remains unchanged after pastes preparation, indicating that the process did not modify the characteristic nanocrystal structure of TiO2. The comparison of [PP@TiO2]P25 (mixture of Anatase and Rutile phases) patterns shows any changement of the Anatase diffraction lines, while the peaks assigned to the Rutile phase are slightly more pronounced, well visible in the Fig. 5 (right panel) in the green shaded areas. Growth and sharpening peaks indicate a weak structural reorganization effects of the structure of the nanocrystalline Rutile phase.

Equilibrium and Kinetic Studies of ARS Adsorption

ARS solution, at acidic pH (2–3), is yellow and present characteristic UV-Vis spectrum with two predominant bands at 261 and 424 nm. Increasing the pH up to 6–7, the bands at 424 nm shift to 510 nm with an increase of the molar extinction coefficient and the solution is strong orange. Fine structure with the presence of two bands at 556 and 596 nm is obtained at basic pH (11–12); in this case the solution is violet and the bands located around 260 nm can be assigned to the π–π* transition of anthraquinone structure (Fig. 6)18.

The ARS adsorption on TiO2 surface in dark condition at 25 °C was first studied using the photoreactor showed in Fig. 7. According to the literature data19, the pH is the major factor that influence the photocatalytic process because affects the adsorption of dye molecules onto TiO2 surface. The adsorption study of ARS on PP@TiO2 conducted at different pH showed that the acidic condition gives the better adsorption efficiency. In fact, the pH condition influences the charge properties of TiO2 and, for higher pH than the point of zero charge (pzc) that, for Aeroxide P-25 is at pH 6.5, the surface becomes negatively charged and it is the opposite for pH < pzc, according to the reaction1,20.

The same acidic condition influences also the chemistry of dye; in fact, ARS structure shows a negative charge on sulphonic group20 and, with pH < 6, an evident adsorption of dye was observed as a result of the electrostatic attraction of the positively charged TiO2 with ARS dye.

Colour change of adsorbed dyes (red) compared to that of the initial dye solutions (yellow) suggest in fact the neutralization of dye charges on the TiO2 surface. It is therefore possible to suppose that with high adsorption capacity of photoactive titanium dioxide, it is possible to improve the efficiency of photo-degradation. For this, to obtain a good knowledge of ARS adsorption mechanism and in order to evaluate how the dye concentration in the original solution influences the adsorption capacity of PP@TiO2 films, different starting ARS concentrations in the adsorption process have been used. Figure 8a shows the UV-Vis spectra change in the solution during the adsorption of ARS on [PP@TiO2]A.

Decrease of UV-Vis spectra in the solution during the adsorption process of 7.30 × 10−5 mol L−1 of ARS on [PP@TiO2]A (a); surface ARS concentration (SC) increasing ARS solution concentrations from 2.92 × 10−5 to 8.77 × 10−5 mol L−1 on [PP@TiO2]P25 (red squares) and [PP@TiO2]A (blue dots) (b); isotherm graphs for ARS on [PP@TiO2]A (c) and on [PP@TiO2]P25 (d).

A common method for defining adsorption equilibrium is the analysis of the “adsorption isotherms”. The surface concentration on TiO2 surface can be calculated by the equation  where Cads is the adsorbed ARS concentration (mol L−1), Vsol is the volume of ARS solution (L) and Afilm is equal to 270 cm2 considering the total area of 9 PP strips.

where Cads is the adsorbed ARS concentration (mol L−1), Vsol is the volume of ARS solution (L) and Afilm is equal to 270 cm2 considering the total area of 9 PP strips.

Figure 8b shows the growth of surface concentration SC (mol cm−2) of ARS on PP@TiO2 films increasing ARS solution concentrations. The [PP@TiO2]A surface had greater absorption capacity compared to that obtained with [PP@TiO2]P25 that showed instead an absorption near to the saturation point of all active sites on TiO2 surface. To establish as the dye concentration influences the adsorption process, the equilibrium data has been analyzed by linear forms of Freundlich (1) and Langmuir (2) isotherms21:

where Ce is the dye solution concentration (mol L−1), Qe is the adsorbed dye amount on TiO2 at equilibrium (mol L−1), KF is the Freundlich constant that represents the adsorption capacity, 1/n is the adsorption intensity, KL and aL are the Langmuir constant and KL/aL represent the theoretical saturation capacity of the TiO2 surface, Q0.

In Fig. 8c,d were reported the linearized isotherm plots that were used to calculate the adsorption constants. The results show that the adsorption data of [PP@TiO2]A fitting Freundlich isotherm model with KF of 9.19 × 10−1 and 1/n of 0.89 (correlation coefficient of 0.944) while for the [PP@TiO2]P25 the best fit is given by the Langmuir model with KL of 2.74, Q0 of 3.84 × 10−5 and aL of 7.13 × 104 (correlation coefficient of 0.989).

According to the Langmuir model it may be deduced that, in the adsorption process on [PP@TiO2]P25, all dye molecules incorporated into the film have similar adsorption energy and the maximum ARS adsorption corresponds to a saturated layer of dye molecules on the adsorbing TiO2 surface that cannot contribute to an additional incorporation of other molecules. However, according to the Freundlich model, it may be deduced that, in the adsorption process on [PP@TiO2]A, multilayer adsorption mechanism can occur22.

These behaviours are explained because [PP@TiO2]P25 presents a regular and uniform structure of the surface, as demonstrated by SEM and AFM measurements and therefore the dye chemisorption is favoured; [PP@TiO2]A shows instead a highly rough surface which permits also high multilayer physical-sorption of dye. These different features explain the greater absorption capacity of [PP@TiO2]A surface respect to [PP@TiO2]P25.

To further characterize the kinetic of adsorption process, the experimental data were compared with different kinetic models and it has been found that a pseudo-first order kinetic well describe the obtained results. The pseudo first order kinetic is expressed by the following equation:

where qt is the amount of adsorbed dye at time t, qe is the equilibrium concentration and k is the first-order adsorption rate constant.

Figure 9a,b show the variation over time of adsorbed dye for different starting ARS concentrations for both [PP@TiO2]A and [PP@TiO2]P25 respectively. The plot of the logarithm term equation (3) versus time t gives optimal straight lines where the slope corresponds to the k value as reported in Fig. 9c for the adsorption of ARS on [PP@TiO2]A and [PP@TiO2]P25 respectively.

The obtained adsorption kinetic constant for [PP@TiO2]A shows that kA does not change for different initial dye concentrations showing mean value of (2.54 ± 0.03) × 10−2 min−1.

However, for [PP@TiO2]P25 film, kD shows a linear dependence on initial dye concentration as may be seen in the Table 1.

Photodegradation Process

ARS solutions in absence of PP@TiO2 are stable under visible light irradiation but, after the adsorption process, the signal of ARS band decreased up to complete disappearance while the colour of PP@TiO2 changes from red to colourless, indicating the photodegradation of ARS with the destruction of their characteristic chromophore; no new adsorption bands appeared in the UV-Vis region.

The photodegradation step, under visible light irradiation, monitored during time by the UV-Vis spectra profile in solution at 424 nm (Fig. 10), demonstrate that this process is slower with respect to the adsorption process, indicating that the reaction occurs on TiO2 surface and not in the solution where the absorbance values are real time monitored.

The variation in time of dye concentration Uv-Vis spectra illustrates that the photodegradation process follows pseudo first order kinetics with respect to dye concentration as shown in equation (4):

where k′ is the pseudo first order kinetic constant, C0 is the initial concentration of dye and C the concentration of dye at t time.

The obtained rate constants values k′A and k′P25 (Table 2) linearly decrease with the increase of initial dye concentration (ARSi) and with adsorbed dye concentration (ARSads) as reported in Fig. 11, showing the influence of catalyst loading in the overall process.

The overall process of adsorption and photodegradation can be resumed in the Fig. 12, while the mechanism is represented schematically in Fig. 13.

Conclusions

Polypropylene coated nano-TiO2 photocatalysts were successfully prepared. The optimization of TiO2 pastes preparation using two commercial TiO2 has been performed and green, low-cost dip-coating procedure was developed.

The study was conducted in three steps. In the first step, Scanning Electron Microscopy, Atomic Force Microscopy and XRD measurements were used to obtain morphological and structural informations of the new heterogeneous photocatalysts on PP support material. Morphological studies demonstrate that [PP@TiO2]A presents major rugosity respect to [PP@TiO2]P25. The analysis of the [PP@TiO2] XRD patterns after pastes preparation reveals that the characteristic nanocrystal structure of TiO2 (presents on each photocatalyst) shows no changement of the Anatase diffraction lines while a weak structural reorganization effect of the Rutile phase, present only on [PP@TiO2]P25, is observed.

In the second step, equilibrium and kinetic aspects of ARS adsorption process were studied showing that the absorption process of ARS followed Freundlich isotherm model with [PP@TiO2]A and Langmuir isotherm model with [PP@TiO2]P25. Obtained KF value of [PP@TiO2]A is 3.35 times higher respect to [PP@TiO2]P25 showing that [PP@TiO2]A has greater absorption capacity compared to [PP@TiO2]P25.

The results of adsorption kinetics revealed that ARS adsorption is kinetically favoured from the increase of initial dye concentration using [PP@TiO2]P25 with kinetic constant value of 2.07 × 10−2 that became about double when the concentration increases of 2.5 factor. On the contrary by using [PP@TiO2]A the kinetic constant value of 2.54 × 10−2 did not change for different initial concentration.

Finally, in the third step, after ARS adsorption in dark condition, kinetic data are obtained from photodegradation process under the action of visible light showing that kinetic constants decrease with the increase of initial ARS concentration for each photocatalyst. However, the results demonstrate that the values obtained by using [PP@TiO2]A are about 20 times higher with respect to [PP@TiO2]P25 at the same initial concentration showing therefore, for this photocatalyst, higher photodegradation activity.

Comparison of the obtained results of [PP@TiO2]A with those of [PP@TiO2]P25, because the differences of two TiO2 starting materials derived only from the presence of rutile phase, it is possible to deduce that the rutile phase presents only on [PP@TiO2]P25 also with a weak structural reorganization, affected the characteristics of adsorption surface and greatly the photodegradation activity.

According to all obtained results it might be confirm that the use of PP@TiO2 in the Visible light photodegradation of ARS permits to obtain efficiently dye degradation, with addition advantage of easy separation of photocatalyst and possibility of reuse, suggesting an application for environmental treatment of waste water.

Methods

Catalyst pastes preparation

Two type of pastes were prepared using TiO2 Aeroxide P-25 and Titanium (IV) dioxide Anatase nano-powdered (<25 nm) (Sigma Aldrich, Code 718467). To create the paste, TiO2 powder (6 g) was ground in a porcelain mortar and mixed with 2 ml of distilled water containing 10% v/v of acetyl acetone (Sigma Aldrich) in order to prevent coagulation of TiO2 nanoparticles. The paste was diluted further with distilled water (8 ml) with continuous grinding for 3 minutes; after, in order to facilitate the spreading of the pastes on the substrate, few drops of a detergent (Triton X-100 Sigma Aldrich) were added. The final addition of water controls the viscosity and the final concentration of pastes.

Polypropylene coated Nano-TiO2 preparation (PP@TiO2)

PP strips (3M Polypropylene 2500 material) of defined size with 2 cm of width and 10 cm of length were prepared and cleaned with ethanol. TiO2 paste (Aeroxide P-25 or Anatase) was added in a cylindrical glass until reaching a determinate level and the paste was stratified on PP strips with the dip-coating technique. After each immersion of 1 minute, the strip is extracted, dried at the room temperature and further dried in the oven at the temperature of ~110 °C for 30 minutes. Finally, the strips are clean up with a solution of water and HCl 0.1 N to remove the excess of TiO2 particles. This procedure is repeated for 3 times in order to obtain PP coated TiO2 strips (PP@TiO2) with an adequate thickness.

Catalyst films characterization

The surface morphology of [PP@TiO2]P25 (Aeroxyde P-25) and [PP@TiO2]A (Anatase), before and after dye adsorption and photocatalytic process, was evaluated by Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM Leica Cambridge Stereoscan) at an accelerating voltage of 20 kV and by Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM Veeco 5000 Dimension) working in tapping mode. For SEM measurements, the strips were attached on aluminium stabs using self-adhesive carbon conductive tabs and sputter coated with gold by Balzers Med 010.

In order to reveal structural variations of the compounds, we also collected some powder x-ray diffraction patterns before and after the adsorption process.

The XRD measurements were collected on a customized horizontal Debye-Scherrer diffractometer, equipped with a INEL CPS 180 curved position sensitive detector that allow to reduce drastically the acquisition time for each pattern. In fact this detector, filled with an Kr/CO2 gas mixture in order to optimize the efficiency, have no moving parts and eliminates the need for mechanical scanning devices such as complex scanning goniometers used in conventional XRD instruments.

The x-ray source is a Mo K-alpha (lambda = 0.7093 Å), generated by a Philips sealed x-ray tube and monochromatized through a graphite crystal along the 002 plane. The samples were positioned on the beam into glass capillaries (diameter 100microns).

Dye adsorption and photodegradation testing

The adsorption (in dark conditions) and photodegradation (under visible light) processes were investigated at acidic pH (by addition of HCl 1.0 N Sigma-Aldrich) using the photo-reactor (Fig. 6).

The reactor is formed by a cylindrical glass vessel with thermostatic chamber (fixed at 25 °C) containing different starting Alizarin Red S (1,2-dihydroxy-9,10-anthraquinonesulfonic acid sodium salt or ARS) dye solutions from 2.92 to 8.77 × 10−5 mol L−1, visible lamp (tubular JD, 80 W, 1375 Lumen DURA), air-line, peristaltic pump Gilson miniplus 3, nine strips of PP@TiO2 and magnetic stirred. The system has been connected with spectrophotometer Hewlett-Packard 8452°. Diode Array with a continuous flux quartz cuvette of optical path of 1 cm, in order to operate in real-time mode. The adsorption and photodegradation processes were separately monitored by measuring the absorbance spectra of dye solutions every 7 minutes at the wavelength maximum of ARS (424 nm); the decrease in concentration of the dye was plotted as function of time.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Giovannetti, R. et al. Visible light photoactivity of Polypropylene coated Nano-TiO2 for dyes degradation in water. Sci. Rep. 5, 17801; doi: 10.1038/srep17801 (2015).

References

Guillard, C. et al. Influence of chemical structure of dyes, of pH and of inorganic salts on their photocatalytic degradation by TiO2 comparison of the efficiency of powder and supported TiO2 . J. Photochem. Photobiol. A: Chemistry 158, 27–36, doi: 10.1016/S1010-6030(03)00016-9 (2003).

Pouretedal, H. R. & Keshavarz, M. H. Study of Congo red photodegradation kinetic catalyzed by Zn1-XCuXS and Zn1-XNiXS nanoparticles. Int. J. Phys. Sci. 27, 6268–6279, doi: 10.5897/IJPS09.251 (2011).

Padikkaparambil, S., Narayanan, B., Yaakob, Z., Viswanathan, S. & Tasirin, S. M. Au/TiO2 Reusable Photocatalysts for Dye Degradation. Int. J. Photoenergy Article ID 752605, 10 pages, doi: 10.1155/2013/752605 (2013).

Thuy, N. M., Van, D. Q. & Hai, L. T. H. The Visible Light Activity of the TiO2 and TiO2:V4+ Photocatalyst. Nanomater. Nanotechnol. 2, art.14, 9 pages, doi: 10.5772/55318 (2012).

Ibhadon, A. O. & Fitzpatrick, P. Heterogeneous Photocatalysis: Recent Advances and Applications. Catalysts 3, 189–218, doi: 10.3390/catal3010189 (2013).

Nakata, K. & Fujishima, A. TiO2 photocatalysis: Design and applications. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C. 13, 168–169, doi: 10.1016/j.jphotochemrev.2012.06.001 (2012).

Quagliarini, E., Bondioli, F., Goffredo, G. B., Cordoni, C. & Munafò, P. Self-cleaning and de-polluting stone surfaces: TiO2 nanoparticles for limestone. Constr. Build. Mater. 37, 51–57, doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2012.07.006 (2012).

Lazar, M. A., Varghese, S. & Nair, S. S. Photocatalytic Water Treatment by Titanium Dioxide: Recent Updates. Catalysts 2, 572–601, doi: 10.3390/catal2040572 (2012).

Herrera-Sandoval, G. M., Baez-Angarita, D. B., Correa-Torres, S. N., Primera-Pedrozo, O. M. & Hernández-Rivera, S. P. Novel EPS/TiO2 Nanocomposite Prepared from Recycled Polystyrene. Mater. Sci. Appl. 4, 179–185, doi: 10.4236/msa.2013.43021 (2013).

Maness, P. C. et al. Bactericidal Activity of Photocatalytic TiO2 Reaction: toward an Understanding of Its Killing Mechanism. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65, 4094–4098 (1999).

Cai, R., Kubota, Y., Shuin, T., Hashimoto, K. & Fujishima, A. Induction of Cytotoxicity by Photoexcited TiO2 Particles. Cancer. Res. 52, 2346–2348 (1992).

Sacco, O. et al. Photocatalytic Degradation of Organic Dyes under Visible Light on N-Doped TiO2 Photocatalysts. Int. J. Photoenergy 2012, 8 pages, Article ID 626759, doi: 10.1155/2012/626759 (2012).

Yu, J., Yu, H., Cheng, B., Zhou, M. & Zhao, X. Enhanced photocatalytic activity of TiO2 powder (P25) by hydrothermal treatment. J. Mol. Catal. A 253, 112–118, doi: 1016/j.molcata.2006.03.021 (2006).

Shan, A. Y., Ghazi, T. I. M. & Rashid, S. A. Immobilisation of titanium dioxide onto supporting materials in heterogeneous photocatalysis: A review. Appl. Catal. A. 389, 1–8, doi: 10.1016/j.apcata.2010.08.053 (2010).

Konstantinou, I. K. & Albanis, T. A. TiO2-assisted photocatalytic degradation of azo dyes in aqueous solution: kinetic and mechanistic investigations A review. App. Catal. B. 49, 1–14, doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2003.11.010 (2004).

Wu, T., Lin, T., Zhao, J., Hidaka, H. & Serpone, N. TiO2-Assisted Photodegradation of Dyes. 9. Photooxidation of a Squarylium Cyanine Dye in Aqueous Dispersions under Visible Light Irradiation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 33, 1379–1387, doi: 10.1021/es980923i (1999).

Augugliaro, V., Loddo, V., Palmisano, G. & Palmisano, L. Clean by Light Irradiation Practical Applications of Supported TiO2, Ch. 2, 41–97 (RSC Publisher, 2010).

Gonzalez, C., Touraud, E., Spinelli, S. & Thomas, O. UV-Visible Spectrophotometry Of Water And Wastewater, Vol.27 (eds Burgess, C., Thomas, O. ) Ch. 3, 47–87 (Elsevier, 2007).

Santhanalakshmi, J., Komalavalli, R. & Venkatesan, P. Photo Catalytic Degradation of Chloropyrifos, Endosulphon, Imidocloprid and Quinolphos by Nano Crystalline TiO2 – a Kinetic Study with pH and Mass Effects. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2, 8–12, doi: 10.5923/j.nn.20120201.02 (2012).

Lachheb, H. et al. Photocatalytic degradation of various types of dyes (Alizarin S, Crocein Orange G, Methyl Red, Congo Red, Methylene Blue) in water by UV-irradiated titania. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 39, 75–90, doi: 10.1016/S0926-3373(02)00078-4 (2002).

Giovannetti, R., Zannotti, M., Alibabaei, L. & Ferraro, S. Equilibrium and Kinetic Aspects in the Sensitization of Monolayer Transparent TiO2 Thin Films with Porphyrin Dyes for DSSC Applications. Int. J. Photoenergy. 9, 1, doi: 10.1155/2014/834269 (2014).

Teoh, Y. P., Moonis, A. K. & Thomas Choong, S. Y. Kinetic and isotherm studies for lead adsorption from aqueous phaseon carbon coated monolith. Chem. Eng. J. 217, 248–255, doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2012.12.013 (2013).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.G. and C.A.D.’A. proposed and designed the experiments. C.A.D.’A. carried out the experiments and conducted the characterization. E.R. preparared Polypropylene coated Nano-TiO2 and performed the SEM characterization, R.G., M.M. and A.D.C. the AFM characterization and structural analysis. R.G., C.A.D.’A. and M.Z. analysed the data. R.G., C.A.D.’A. and M.M. wrote the manuscript. All the authors participated in discussions of the research.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Giovannetti, R., Amato, C., Zannotti, M. et al. Visible light photoactivity of Polypropylene coated Nano-TiO2 for dyes degradation in water. Sci Rep 5, 17801 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep17801

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep17801

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

Room temperature fabrication of cobalt mullite for the snappy adsorption of cationic and anionic dyes

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2023)

-

TiO2 based nanomaterial: Synthesis, structure, photocatalytic properties, and removal of dyes from wastewater

Korean Journal of Chemical Engineering (2023)

-

Facile one-pot solvothermal-assisted synthesis of uniform sphere-like Nb2O5 nanostructures for photocatalytic applications

Research on Chemical Intermediates (2019)

-

Synthesis of AG@AgCl Core–Shell Structure Nanowires and Its Photocatalytic Oxidation of Arsenic (III) Under Visible Light

Nanoscale Research Letters (2017)