Abstract

We investigated the putative redundancy of the Dark Tetrad (specifically, Machiavellianism-psychopathy and sadism-psychopathy) through an examination of the differences between correlations with self-reported narrowband personality traits. In addition to measures of the Dark Tetrad, participants in four studies completed measures of various narrowband traits assessing general personality, aggression, impulsivity, Mimicry Deception Theory, and Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory. Results generally supported empirical distinctions between Machiavellianism and psychopathy, and between sadism and psychopathy. Machiavellianism significantly differed from psychopathy across correlations for nine of 10 traits (Study 1), 8 of 25 facets (Study 2), aggression (Study 3), 12 of 25 facets (Study 3), four of five facets (Study 4), impulsivity (Study 4), and five of six facets (Study 4). Sadism significantly differed from psychopathy across correlations with five of 10 traits (Study 1), eight of 25 facets (Study 2), reactive aggression (Study 3), 10 of 25 facets (Study 3), three of six facets (Study 4), impulsivity (Study 4), and three of six facets (Study 4). Our findings challenge the claims that Machiavellianism and psychopathy, as well as sadism and psychopathy, as currently measured, are redundant.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Dark Tetrad, first introduced by Paulhus and Williams as the Dark Triad1, comprises four socially malevolent personality traits including narcissism, Machiavellianism, psychopathy, and sadism. Although diagnostic conceptualizations of narcissism, psychopathy, and sadism exist for use among forensic or clinical populations, the Dark Tetrad traits are measured at the subclinical level (i.e., in the general community) as personality traits along a continuum. Subclinical narcissism has been described as involving heightened grandiosity, dominance, entitlement, and superiority2. Individuals scoring high in narcissism tend to engage in self-promotion and exploitation of others to achieve their goals3. Subclinical psychopathy comprises affective and behavioral components largely derived from early work by Cleckley4, including callousness, dishonesty, blunted affect, impulsivity, and superficial charm5. Subclinical sadism reflects a tendency to derive pleasure from others’ suffering6. Machiavellianism is characterized as having a strategic, exploitative personality style as well as cynical views of others7. Unlike the other Dark Tetrad traits, Machiavellianism emerged from the seminal work of Niccolo Machiavelli (i.e., The Prince8), rather than from clinical or forensic settings.

Each of the Dark Tetrad traits share common features, such as manipulation and callousness9, although they were originally proposed as distinct constructs1,10 Despite a large corpus of research, major debates continue surrounding whether these traits—specifically, Machiavellianism and psychopathy, as well as sadism and psychopathy—are functionally redundant, as currently measured (see Kowalski et al.11 for review). Extending the work of Kowalski et al.12, the present article contributes to this debate by exploring the differential validity between Machiavellianism and psychopathy, as well as between sadism and psychopathy, through an examination of the differences in bivariate correlations with narrowband personality constructs.

The dark tetrad redundancy debate

Although the Dark Tetrad traits are conceptually distinct, some meta-analyses have argued that they are not distinct enough to be considered separate constructs13,14. In a broader sense, the dark traits may appear similar because they are all associated with interpersonal difficulties and a lack of empathy1. Research investigating the inclusion of sadism in the now-expanded Dark Tetrad has suggested that psychopathy and sadism have considerable statistical overlap. Sadism and psychopathy have strong significant correlations15,16. Additionally, sadism has failed to demonstrate incremental validity in the context of moral decision-making17 and perceiving victim vulnerability18, suggesting statistical redundancy. Nonetheless, evidence from other contexts supports sadism as a distinct trait within the Dark Tetrad. For instance, sadism has demonstrated incremental validity in the prediction of interpersonal deviance, instigated incivility, and frequency of cyberbullying19. Furthermore, in an exploratory factor analysis of Dark Tetrad traits, sadism (specifically, physical sadism) demonstrated some degree of overlap with psychopathy; however, the factor analysis identified six distinct factors: narcissism, Machiavellianism, psychopathy, verbal sadism, physical sadism, and vicarious sadism20.

Paulhus and Williams, and Kowalski et al. have shown that the Dark Tetrad traits vary in their association with the Big Five dimensions, as well as their lower-order facets1,12. The distinctions between the Dark Tetrad traits are further pronounced when investigating behavioral outcomes, such as relationship infidelity21 or heritability22. For example, although psychopathy and Machiavellianism have both been implicated in relationship infidelity, only psychopathy predicted the termination of the relationship21. Vernon et al. also demonstrated that the traits differ in their heritability, such that psychopathy and narcissism had a larger heritable component than Machiavellianism22 (for a more in-depth description of the redundancy debate, see Kowalski et al.11).

Settling the redundancy debate

Although extensive research has been conducted to address this redundancy debate, it remains unresolved. One strategy proposed for disentangling the dark traits is to assess differences in correlations using narrowband self-report measures of theoretically relevant variables12. This idea was based on the observation that research using behavioral or situational measures of external correlates23,24 has generally led to different conclusions than those using broad self-report measures18,25,26. For example, behavioral measures of impulsivity, which often differentiate psychopathy from Machiavellianism, capture a narrower impulsivity dimension compared to those typically captured by self-report measures, which often fail to differentiate psychopathy from Machiavellianism11,27,28. The narrowband approach assumes that there is substantial overlap between the dark traits and therefore focuses on subtle characteristics that may differentiate them while avoiding the “perils of partialling” problem11,29.

Much of the previous research purporting to address the redundancy debate has implemented multivariate statistical analyses, usually multiple regression, to assess the incremental contribution of the constructs in predicting certain outcomes30. This approach, although informative, has been criticized14,29,31, and authors note that this multivariate approach—to the exclusion of bivariate correlations—relies on the interpretation of residualized variables, which may not be comparable to assessing raw variables in which the shared variance is included (i.e., “perils of partialling”). To avoid conceptual issues with interpreting residualized variables, it is instead recommended that researchers examine bivariate correlations and conduct tests of differences between dependent correlations31. Although this is rarely done in practice31, a recent attempt to disentangle the Dark Tetrad traits32 found that latent psychopathy and latent sadism are similar in terms of their relationships with outcome variables within their respective nomological networks. Depending on the measures used, between five and 20 significant differences were found between sadism and psychopathy out of a total of 51 criteria (using p < 0.001). Although Blötner and Mokros interpreted this as evidence that, as currently measured, psychopathy and sadism are at least near-equivalent32, we instead see this as evidence of their distinction, as 20 of 51 distinct sets of correlations is not a negligible number, especially given the conservative p-value of 0.001.

Building on this, we propose that a more optimal approach is to compute effect sizes for the differences so that the interpretation of difference is not partially dependent on sample size, as is the case when relying on significance tests. Because our approach focuses on narrow bandwidth correlates of the dark traits, it is more sensitive to potential differences between construct associations, since measurement is more precise for narrow than broad bandwidth dimensions33. For example, individuals scoring high on psychopathy and Machiavellianism may act similarly on their impulses, but when positive or negative consequences are made salient, behaviors may differ substantially across contexts11. This result is corroborated by evidence that individuals who score high on Machiavellianism tend to be more sensitive to situational variables34.

The topic of construct bandwidth is not new; the performance of broad versus narrow bandwidth traits has been debated vigorously within the psychological literature. Paunonen et al. specifically posited that the prediction of criteria is more precise and that interpretability is improved when using multiple narrow predictors relative to their overarching broad traits35. A plethora of research has since supported this view36,37. Other researchers have argued for the principle of Brunswik symmetry, in that narrowband dimensions are better at predicting narrow-bandwidth criteria, whereas broad-bandwidth constructs are better at predicting broad-bandwidth criteria38,39. Considering the focus of the present study is on the potentially subtle differences between the Dark Tetrad traits, and not broad common variance, both these perspectives support the use of narrow bandwidth traits for the purposes of potentially differentiating psychopathy and Machiavellianism, and between psychopathy and sadism.

The present studies

The overall objective of the following four studies was to clarify the putative potential redundancy between the Dark Tetrad traits. Specifically, we assessed the magnitude of correlation differences between measures of narrowband constructs and psychopathy/sadism, and between psychopathy/Machiavellianism across multiple independent samples. Note that, for completeness, we include in each study the descriptive and bivariate correlations with narcissism but do not focus our discussion on this construct.

In Study 1, we evaluated differences in relationship strength with traits from the Supernumerary Personality Inventory (SPI)40. In Study 2, we compared correlations between the Dark Tetrad and lower-order facets and higher-order domains of the HEXACO model of personality41. In Study 3, we focused on correlations with facets of the Personality Inventory for the DSM-5 (PID-5)42 and the Reactive–Proactive Aggression Questionnaire (RPAQ)43.

For Study 4, rather than relying on a largely atheoretical approach that considers a full range of personality dimensions, we focused on narrowband constructs expected to demonstrate distinct correlations with sadism and psychopathy, and with psychopathy and Machiavellianism. These include measures of impulsivity44, Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory45, Dickman’s theory of impulsivity46, and Mimicry-Deception Theory47.

Study 1

Previous research has established that there is more to personality than the Five-Factor Model48,49. The SPI was developed to capture personality variance that was inadequately represented in the Five-Factor Model using a narrowband trait approach40,50,51. Research on the content domain of the SPI has found that the SPI does account for unique variance in personality scores beyond the Five-Factor Model and the HEXACO models; additionally, in line with research on the functionality of narrow traits52, the narrow SPI traits have been found to improve the prediction of specific behaviors, including donation, pro-environmental activities, materialism, and unethical behaviors50,53,54.

Accordingly, to assess the differential validity of the traits that comprise the Dark Tetrad, we examined relationships with the narrow SPI traits. In doing so, we hoped to identify different patterns and strengths of relations amongst the traits. Importantly, previous research has indeed examined the relationship between the 10 SPI traits and the original Dark Triad traits51. Veselka and colleagues found that except for conventionality, psychopathy and Machiavellianism were significantly correlated with each of the traits on the SPI51.

Based on the research summarized above, we hypothesized that Machiavellianism would positively correlate with seductiveness, manipulation, humorousness, risk-taking and egotism and negatively correlate with thriftiness, integrity, femininity, and religiosity. Psychopathy was predicted to positively correlate with seductiveness, manipulativeness, humorousness, risk-taking and egotism and negatively correlate with thriftiness, integrity, femininity, and religiosity.

We are not aware of any published research on the relationship between sadism and the SPI traits. Accordingly, we advanced no specific hypotheses regarding these relationships and instead treated the correlations as exploratory.

Method

Participants and procedure

In total, 532 students from a large North American university consented to complete the scales on-line and received a research credit. After removing careless responders, 424 remained. Participant ages ranged from 18 to 66 years (M = 19.67, SD = 3.28), and most participants were women (62%). Two individuals did not indicate their gender. This study was approved by the University of Western Ontario Research Ethics Board and all methods were carried out in accordance with ethical guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Measures

Unless otherwise stated, participants responded to all measures using a 5-point Likert-type scale, with anchors ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree).

Supernumerary personality inventory

The SPI is a self-report measure of personality traits beyond the Big Five and HEXACO personality models40,51,55. The measure contains ten 15-item scales: conventionality, seductiveness, manipulativeness, thriftiness, humorousness, integrity, femininity, religiosity, risk-taking, and egotism. Paunonen provided evidence in favour of acceptable-to-excellent the reliability and validity of the SPI (α’s = 0.67 to 0.95)40.

Narcissistic personality inventory

The Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI)2 is a self-report measure of subclinical narcissism containing 40 forced-choice items, which require participants to respond by selecting one of two options (e.g., I am an extraordinary person; I am much like everybody else). Previous research has reported evidence in support of the validity and reliability of the NPI (α = 0.84)1.

Assessment of sadistic personality: 8-item version

The Assessment of Sadistic Personality-8 (ASP-8) is an eight item, self-report measure of subclinical sadism56. The scale has demonstrated evidence of excellent reliability and validity (α = 0.84 to 0.91)56.

MACH-IV

The MACH-IV is a 20-item, self-report measure of Machiavellianism7. Previous research has reported good internal consistency reliability (0.74) and has provided evidence of validity57.

Self-report psychopathy scale-III-R12

The Self-Report Psychopathy Scale-III-R12 (SRP-III)58 is a 62-item self-report measure of subclinical psychopathy. The measure has good reliability (α = 0.79), and the authors have provided evidence of validity58.

Results and discussion

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations

Descriptive statistics, bivariate correlations, and internal consistency reliabilities for all study variables are presented in Table 1. Most internal consistency reliabilities in the sample were acceptable (α > 0.70). However, consistent with observations by other researchers using the SPI50,53, lower reliabilities were observed for conventionality (α = 0.68). To maximize the sample size for analyses with missing data, pairwise deletion was used.

Among the Dark Tetrad traits, the strongest correlation was observed between sadism and psychopathy, which is consistent with previous findings16,59. Moderately strong correlations were also observed between psychopathy and Machiavellianism.

In relation to the SPI traits, each Dark Tetrad trait was significantly correlated with manipulativeness, integrity, and femininity. This pattern of trait relationships is conceptually aligned with the “core” of the Dark Tetrad. One interpretation for the shared variance among the Dark Tetrad traits is callousness (c.f. low femininity) and interpersonal manipulation (c.f. low integrity, high manipulativeness)9,60, which neatly maps onto these SPI scales.

Points of distinction among the Dark Tetrad traits were explored further by considering the differences in the magnitudes of the relationships with the SPI scales, as described in the next section.

Difference tests for correlations

To examine whether differences between pairs of correlations were statistically significant, Steiger’s z-test was conducted using Lee and Preacher’s online calculator (http://quantpsy.org/corrtest/corrtest2.htm). 61 Specifically, the magnitude of the correlations with SPI traits were contrasted between Machiavellianism and psychopathy, and between sadism and psychopathy (see Table 2). Effect sizes (Cohen’s q) were computed using Lenhard and Lenhard’s online calculator (https://www.psychometrica.de/effect_size.html). 62.

Compared to both Machiavellianism and sadism, psychopathy had significantly stronger relationships with humorousness, seductiveness, manipulativeness, femininity, egotism, and risk-taking. Given that femininity and manipulativeness are both conceptually aligned with the “core” of the Dark Tetrad (i.e., callousness and interpersonal manipulation), this may indicate that psychopathy is more central to the Dark Tetrad than are Machiavellianism and sadism. The measure of psychopathy administered (i.e., SRP-III) also contains subscales that reflect this core (e.g., Interpersonal Manipulation; Callous Affect). These additional uniquely stronger relationships with seductiveness, egotism, and risk-taking are consistent with relationships between psychopathy and self-reported promiscuity63, self-centered antagonism64, and sensation-seeking/impulsivity63,65. These relationships highlight elements of uniqueness for the psychopathy construct.

Compared to Machiavellianism, psychopathy had significantly stronger relationships with conventionality and integrity, and a significantly weaker relationship with religiosity. Differences for these specific SPI traits were not significant for psychopathy and sadism. These findings were anticipated, since sadism and psychopathy have been similarly linked to such traits as low honesty-humility20 and religiosity (non-significant)66 in past research.

Study 2

Kowalski et al. demonstrated that Machiavellianism differed significantly (i.e., p < 0.01) from psychopathy in correlations with 12 of 30 Big Five facets12. As previously mentioned, Paunonen and Jackson challenged the comprehensiveness of the Big Five by outlining 10 dimensions inadequately covered by the Big Five personality space (i.e., the SPI traits)49. Subsequently, a competing personality model has been proposed (i.e., the HEXACO model)67, which includes Honesty-Humility (H), Emotionality (E), Extraversion (X), Agreeableness (A), Conscientiousness (C), and Openness to Experience (O). Since the introduction of the HEXACO, research has supported it as a more comprehensive model of personality68, especially for morality or “darker” traits69,70. Moreover, the HEXACO model has been shown to have strong predictive power for behaviors that are relevant to maladaptive personality, such as workplace deviance (especially at the facet-level)71, aggression72, externalizing problems in adolescents73, and revenge74. Some scholars have argued that the “core” of the Dark Tetrad, at minimum, shares many similarities with Honesty-Humility75,76. Extending Kowalski et al.’s research12 by assessing differences between the Dark Tetrad traits in their correlations with HEXACO facets would provide further evidence for potential non-redundancy of psychopathy, sadism, and Machiavellianism, which was the objective of Study 2.

Hypotheses

Based on past findings72,77, we hypothesized that the Dark Tetrad traits would be differentially related to the broad HEXACO factors6. We predicted that Extraversion would be strongly and negatively correlated with sadism, psychopathy, and Machiavellianism. Openness to Experience was predicted to correlate negatively with sadism, psychopathy, and Machiavellianism. We further expected that Machiavellianism would demonstrate a significantly weaker association with Emotionality than psychopathy. For Conscientiousness, we anticipated that Machiavellianism would exhibit a significantly smaller negative correlation than psychopathy. These predictions were based on the defining features of psychopathy, including lack of remorse or anxiety associated with their behaviors, as well as impulsivity and lack of planning1. Lastly, we did not anticipate significant differences between the Dark Tetrad traits in terms of the direction of their relationships with Honesty-Humility78; however, we expected that sadism would have a significantly stronger negative relationship with Honesty-Humility and its facets than psychopathy6,76.

Given the paucity of research assessing HEXACO facets in relation to the Dark Tetrad traits, these associations were exploratory; therefore, no explicit facet-level relationship differences were hypothesized.

Method

Participants and procedure

In total, 1,058 students from a large North American university consented to complete the scales on-line and received a research credit. After removing careless responders, 830 participants remained. Participant ages ranged from 16 to 42 years (M = 18.81, SD = 2.99), and most participants (69.6%) were women. Nine participants did not disclose their gender. This study was approved by the University of Western Ontario Research Ethics Board and all methods were carried out in accordance with ethical guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Measures

Participants responded to all measures using a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree), unless stated otherwise.

Dark tetrad

All measures of the Dark Tetrad were the same as Study 1.

HEXACO-100

The 100-item version of the HEXACO-PI-R measures six broad personality dimensions, which are composed of four narrow facets, each measured by four items67. The authors of the HEXACO-100 have provided evidence of acceptable-to-good reliability and validity. Internal consistency reliability of the broad factors ranges from 0.82 to 0.89 and narrow facets range from 0.64 to 0.8048.

Results and discussion

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations

Descriptive statistics, internal consistency reliability, and bivariate correlations for all variables are presented in Table 3. Most scales demonstrated acceptable internal consistency (α > 0.70). The lower reliabilities observed for some of the HEXACO facets is consistent with those previously observed by Lee and Ashton in their large sample of university students48. To maximize the sample size for analyses with missing data, pairwise deletion was used.

Among the Dark Tetrad traits, the same pattern and magnitude of intercorrelations observed in Study 1 was replicated. At the broad factor level, each Dark Tetrad trait was most strongly correlated with Honesty-Humility, which replicates multiple findings. Additionally, Emotionality, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness were also negatively correlated with the Dark Tetrad traits. These factor-level patterns were generally replicated at the facet level, although the magnitude of the correlations varied between traits, aligning with theoretical expectations.

Psychopathy had significantly stronger relationships with Emotionality as well as its four facets (see Table 4). The effects observed were mostly small, with negligible differences observed for dependence and sentimentality. Psychopathy also had a significantly stronger relationship with Conscientiousness and its organization, perfectionism, and prudence facets. Again, observed effects were small, except for the absence of any effect in the difference in relationships with organization. Psychopathy also had significantly stronger relationships with aesthetics and unconventionality; however, the effect size was negligible.

Difference tests for correlations

Following Study 1, Steiger’s z-test was used to evaluate the significance of the difference between Machiavellianism and psychopathy, and between sadism and psychopathy, in the size of their correlations with the HEXACO facets. Compared to both Machiavellianism and sadism, psychopathy had significantly stronger relationships with all facets of Emotionality, as well as social boldness, organization, perfectionism, prudence, and unconventionality. Compared to Machiavellianism, psychopathy had significantly weaker relationships with forgiveness, gentleness, and creativity. Psychopathy also had weaker correlations than Machiavellianism with all facets of Extraversion except for social boldness, for which it had a stronger relationship. Psychopathy also had significantly stronger relationships with aesthetic appreciation. Compared to sadism, psychopathy had significantly stronger relationships with fairness and sincerity, but a weaker relationship than sadism with inquisitiveness.

Study 2’s hypotheses regarding the relationships between Machiavellianism and the HEXACO facets were supported. All but three hypotheses concerning relationships between psychopathy and the HEXACO facets were supported. Surprisingly, neither psychopathy nor sadism was significantly correlated with Extraversion, nor with the social self-esteem and liveliness facets of Extraversion, as was predicted. In terms of associations between sadism and the HEXACO traits, four of five hypotheses were supported. As predicted, sadism exhibited negative correlations with Honesty-Humility, Emotionality, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness, including their respective facets. Notably, the nonsignificant correlation between sadism and Extraversion contradicts previous research reporting negative relationships6,20.

With respect to the distinctiveness of psychopathy-sadism and psychopathy-Machiavellianism, results provide modest evidence of non-redundancy. Specifically, Machiavellianism and psychopathy differed significantly in their correlations between 20 of the HEXACO traits and facets, with mostly small effect sizes (12 small effects with coefficients ranging from 0.1 to 0.3 and eight effects with coefficients lower than 0.1, indicating a negligible effect size). Sadism and psychopathy also differed significantly in their correlations with 16 of the HEXACO traits and facets: 11 of these had small effects, and five had no observed effects.

Study 3

Evidence reported by Kowalski et al.12 and Studies 1 and 2 above contribute to the literature differentiating the Dark Tetrad traits by testing the differences with general personality models. Recently, a new model of maladaptive personality traits based on the DSM-V has been introduced. The PID-5 is described as a comprehensive assessment of maladaptive personality variation at the facet-level (e.g., manipulativeness, deceitfulness, callousness; for a complete list with definitions, refer to Krueger & Markon79). Previous research has shown that many of the facets of the PID-5 model predict outcomes that are relevant to the Dark Tetrad, including aggression80,81 and sexual violence82,83.

Aggression is often cited as an outcome associated with dark traits71,84,85,86,87. The Reactive-Proactive Aggression Questionnaire (RPQ)43 distinguishes between two different types of aggression based on the underlying motivation. Reactive aggression refers to a defensive reaction to others’ attacks, insults, or provocations, while proactive aggression refers to unprovoked acts of aggression88. Previous studies investigating the relationship between the Dark Tetrad and these types of aggression have relied on brief measures of the dark traits71,86,89, which tend to overemphasize the shared variance of the Dark Tetrad constructs90,91 and did not use correlation difference tests to determine if the dark traits differed in terms of reactive or proactive aggression. These limitations do not allow for an assessment of the differences or redundancy of Machiavellianism and psychopathy, and sadism and psychopathy.

Following the same general methodology and analytical procedures as Studies 1 and 2, Study 3 compares correlations between the Dark Tetrad traits with PID-5 facets, as well as proactive and reactive aggression, using full-length measures of the Dark Tetrad traits.

Hypotheses

Based on recent empirical studies evaluating associations between the PID-5 and the Dark Tetrad traits6,16,92, we hypothesized that psychopathy would demonstrate stronger positive correlations with facets related to detachment (e.g., withdrawal, anhedonia, depressivity, intimacy avoidance), antagonism (e.g., callousness), disinhibition (e.g., irresponsibility, impulsivity, distractibility, risk-taking), and psychoticism (e.g., perceptual dysregulation) than Machiavellianism. Given mixed findings related to negative affectivity facets and the Dark Tetrad traits, we did not make predictions regarding these associations. Finally, given high levels of irresponsibility and impulsivity associated with psychopathy1, we anticipated that psychopathy would exhibit stronger positive relationships with disinhibition facets (e.g., impulsivity, distractibility, irresponsibility) than with sadism91.

Because individuals who score high in psychopathy tend to impulsively aggress in response to perceived threats and to proactively aggress to attain a goal6, we hypothesized that psychopathy would be more strongly and positively correlated with both reactive and proactive aggression than Machiavellianism would be. This prediction is further based on empirical research assessing the relations between the Dark Triad and various types of aggression71,93. Given the strong theoretical ties to pleasure-driven cruelty59, we also anticipate that sadism will exhibit stronger correlations with proactive aggression than would psychopathy6.

Method

Participants and procedure

Students (N = 510) from a large North American university consented to complete the scales on-line and received a research credit for simply starting the study. After removing careless responders, 382 participants remained. Participant ages ranged from 18 to 75 (M = 19.70, SD = 4.51), and most participants (72.8%) were women. Ten participants did not disclose their gender. This study was approved by the University of Western Ontario Research Ethics Board and all methods were carried out in accordance with ethical guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Measures

Participants responded to all measures in the study using a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree), unless stated otherwise.

Dark tetrad

All measures of the Dark Tetrad were the same as Study 1.

The personality inventory for the DSM-5 (PID-5)

The PID-5 is a measure of maladaptive personality traits as described by the DSM-542. This measure uses 100 items to measure 25 facets, and participants responded to this measure using a 4-point response scale ranging from 0 (Very false) to 3 (Very true). The authors of the measure provide evidence of good-to-strong reliability (α = 0.73—0.96) and validity.

The reactive-proactive aggression questionnaire (RPQ)

The RPQ is a 23-item self-report measure of reactive (11-items) and proactive trait aggression (12-items) responded to using a 3-point scale with responses ranging from 0 (Never) to 2 (Often)43. The authors of the measure provide evidence of good-to-strong reliability (α = 0.81—0.91) and validity.

Results

Descriptives and bivariate correlations

Descriptive statistics, internal consistency reliabilities, and bivariate correlations for all variables are presented in Table 5. All scales except for Irresponsibility, Perceptual Dysregulation, and Suspiciousness demonstrated acceptable internal consistency (α > 0.70). Given the brevity of these scales (i.e., 4 items each), they may reflect less heterogenous constructs. As with Studies 1 and 2, pairwise deletion was used to maximize the sample size used in analyses.

Among the Dark Tetrad traits, the same pattern and magnitude of intercorrelations observed in Studies 1 and 2 were replicated. Among the RPQ scales, Dark Tetrad traits were positively correlated with both self-reported proactive aggression and self-reported reactive aggression, with relationships ranging from weak to moderately strong. Numerous significant relationships were observed between the Dark Tetrad traits and the PID scales. Notably, moderate and large correlations were observed for all Dark Tetrad traits with callousness, deceitfulness, grandiosity, and manipulativeness. Other PID scales related to the Dark Tetrad traits (e.g., restricted affectivity) had more varied relationships, including some weaker relationships. These narrow characteristics are conceptually related to the “dark core” of callousness and interpersonal manipulation.

Difference tests for correlations

As with Studies 1 and 2, Steiger’s z-test was used to evaluate the significance of the difference in the size of the correlations between Machiavellianism/psychopathy, and between sadism/psychopathy, for each of the scales on the RPQ and the PID (see Table 6). Correlations with self-reported proactive reaction differed between psychopathy and Machiavellianism, but not with sadism. Psychopathy had a stronger correlation with self-reported reactive aggression than with Machiavellianism, but a weaker correlation than with sadism.

Among the PID scales, psychopathy had significantly stronger correlations with anxiousness, deceitfulness, manipulativeness, risk-taking, and submissiveness. Psychopathy also had a significantly weaker correlation with withdrawal. Correlations with emotional lability also differed significantly; however, none of the individual correlations were significant, making these differences difficult to interpret. Compared to Machiavellianism, psychopathy had significantly stronger correlations with impulsivity, irresponsibility, and unusual beliefs. Psychopathy had significantly weaker correlations with depressivity and perseveration. Compared to sadism, psychopathy had a significantly stronger correlation with restricted affectivity. However, psychopathy had a weaker correlation than sadism with hostility and separation insecurity.

Study 4

Although Studies 1 to 3 are informative regarding the redundancy debate, as is the previous work by Kowalski et al.12, a limitation of these investigations is that most of the variables used have not been chosen based on a theoretical justification, but rather because of the comprehensive nature of these taxonomies (e.g., Big Five facets, SPI, HEXACO facets, PID-5 facets). It would be reasonable to predict that an investigation which considered constructs that should differentiate these traits based on theory would be a more effective way of finding differences in traits, if they exist.

One such construct is impulsivity. Numerous studies have investigated the dark traits in relation to impulsivity17,94. Theoretical accounts of high impulsivity inherent in psychopathy are consistently corroborated by empirical findings17,93,95,96, though this relationship is found less consistently with behavioral measures of impulsivity, likely due to the multi-faceted nature of impulsivity17,97. Theoretical accounts of Machiavellianism emphasize strategic manipulation and long-term planning7, which seem to be inconsistent with impulsive, spur-of-the-moment behavior. Empirically, however, research has been inconsistent, with some self-report findings demonstrating nonsignificant relationships with impulsivity17,93,95, while other self-report findings demonstrating positive correlations between Machiavellianism with impulsivity17,98.

Despite these inconsistencies, behavioral research tends to support a theoretically consistent differentiation between Machiavellianism and psychopathy based on impulsivity99. Reasons for the inconsistency in the Machiavellianism-impulsivity link have been described in previous papers. For example, Kowalski et al. suggested that inconsistent findings are due to behavioral measures tending to be narrower than many self-report measures12. On the other hand, Kowalski et al. contended that much of the research which fails to differentiate psychopathy from Machiavellianism (much of which focuses on relations to impulsivity) employ short measures of the Dark Triad11, which are known to overemphasize overlapping characteristics of the dark traits89. In the present study, we assess narrowband conceptualizations of impulsivity and the measures of the Dark Tetrad so that we could better observe unique relationships with self-report assessments of impulsivity.

Dickman’s dysfunctional and functional impulsivity typology

Many different conceptualizations of impulsivity exist in the literature. In the present study, we used Dickman’s dysfunctional and functional impulsivity typology, which posits two weakly-correlated impulsivity constructs46. Dysfunctional impulsivity is defined as the tendency to act with less forethought, while functional impulsivity is the tendency to act with little forethought when such an approach is useful46.

Reinforcement sensitivity theory

The Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory (RST)45 conceptualization of impulsivity was also included in the present study. Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory, originally based on the work of Gray100, proposes two general biological mechanisms that modulate behavior: the Behavioral Inhibition System (BIS), which is responsible for aversive responses (i.e., anxiety responses towards situations that may lead to negative consequences such as punishment or pain), and the Behavioral Activation System (BAS), which regulates appetitive behavior (i.e., approach behavior towards situations which may elicit rewards101,102. Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory has previously been linked to the Dark Tetrad traits103,104,105,106 and has been put forward as an explanation for phenomena such as antisocial behavior107, risk-taking108, internet trolling103, and malevolent creativity109. Many RST measures have been developed; however, the one currently used most frequently is the Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory of Personality Questionnaire (RST-PQ)45, which includes six factors: two unitary defensive factors (Fight-Flight-Freeze System and BIS) and four approach factors (Reward Interest, Goal-Drive Persistence, Reward Reactivity, and Impulsivity). It should be noted that Dickman’s conceptualization of impulsivity and those proposed by RST are not orthogonal46,110. Therefore, we caution against interpreting the impulsivity measures as completely independent from each other.

UPPS-P

Another conceptualization of impulsivity is the UPPS-P model44,111, which proposes five dimensions of impulsivity: negative urgency (the inclination to act thoughtlessly when experiencing negative emption), lack of perseverance (inability to remain focused on difficult or tedious tasks), lack of premeditation (disposition to not think through potential consequences of action), sensation-seeking (seeking excitement and openness to new experiences), positive urgency (the disposition to act thoughtlessly when in the presence of positive emotion). This model has been well validated and used to predict such outcomes as problem gambling112. Previous research has employed the UPPS-P model as a basis to discriminate between the Dark Triad traits. Kiire et al. found that psychopathy incrementally predicted each UPPS-P dimension over the effects of the other Dark Triad traits, and that Machiavellianism incrementally predicted lack of perseverance, and lack of premeditation99. It should be noted, however, that the study by Kiire et al. was subject to the “perils of partialling,” since the authors used multiple regression to differentiate between the traits, as well as a short measure of the Dark Triad, issues for which the present study was designed to avoid99.

Mimicry deception theory

Mimicry Deception Theory (MDT) has been proposed as a framework which should theoretically discriminate between Machiavellianism and psychopathy47. Thus, the Dark Tetrad traits will be compared in their relations to MDT dimensions. Mimicry Deception Theory purports to explain differences in deception strategies in terms of long or short-term goals by dividing these strategies into four dimensions: community integration, complexity of deception, resource extraction, and detectability47. According to Jones, long-term oriented deceivers tend to integrate into their communities, use more complex deceptive tactics and gradual resource extraction, and use tactics that are more difficult to detect47. Short-term-oriented deceivers tend to integrate less into communities, use less-complex forms of deception with rapid resource extraction, and are more detectable in their deception. Jones’s assertions were supported by research which analyzed reports from victims of deceptions and found that these components are not only positively intercorrelated, but that these components predicted post-deception doubt and amount of money lost113. Jones hypothesized that a long-term orientation in deception is descriptive of Machiavellianism, while a short-term orientation is descriptive of psychopathy. This claim was partially supported by de Roos and Jones114.

Hypotheses

Based on previous findings using the UPPS-P98, we hypothesized that psychopathy would positively correlate with both negative urgency and positive urgency, which will be stronger than those observed for Machiavellianism. We also predicted that psychopathy will demonstrate a significant positive correlation with lack of perseverance. In contrast, given previous research supporting a willingness for sadistic individuals to exert effort to inflict pain on others59, we predicted that sadism will show a significantly weaker, or possible negative correlation with lack of perseverance; however, did not anticipate significant correlations for Machiavellianism. For lack of premeditation, we predicted a negative correlation with Machiavellianism and a positive correlation with psychopathy.

We also predicted that sensation-seeking would be strongly positively correlated with psychopathy and weakly or non-significantly correlated with Machiavellianism. Aside from the correlation between sadism and lack of perseverance, we did not make predictions for sadism, as this is a relatively new area of research related to the full Dark Tetrad.

Using Dickman’s measures of functional and dysfunctional impulsivity, we further hypothesized that dysfunctional impulsivity would be more strongly positively correlated with psychopathy than Machiavellianism115. This is based on the theory that impulsivity is more strongly related to weak self-regulation skills for those high in psychopathy116. We did not develop specific hypotheses for sadism, as functional and dysfunctional impulsivity have not yet been evaluated in the context of the full Dark Tetrad.

Based on preliminary research conducted by de Roos and Jones114, we further hypothesized that Machiavellianism would be significantly and positively correlated with Mimicry Deception Scale (MDS) complexity of deception, community integration, resource extraction, and detectability, and that psychopathy would be significantly and positively correlated with resource extraction. Notably, de Roos and Jones114 found that the correlation between composite MDS scores and Machiavellianism was significantly stronger than for psychopathy. These hypotheses are rooted in theory reflecting the long-term, strategic manipulative, planful nature of Machiavellianism1.

Finally, relationships between the Dark Tetrad and RST-PQ facets are exploratory, as previous research has not yet investigated these relationships.

Method

Participants and procedure

In total, 851 students from a large North American university consented to complete the scales on-line and received a research credit. After removing careless responders, 655 participants remained. Participant ages ranged from 16 to 52 years (M = 19.09, SD = 3.70), and participants were mostly (72.5%) women. Seven participants did not disclose their gender. This study was approved by the University of Western Ontario Research Ethics Board and all methods were carried out in accordance with ethical guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Measures

Participants responded to all measures in the study using a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree), unless stated otherwise.

Dark tetrad

All measures of the Dark Tetrad administered were the same as Study 1.

Functional and dysfunctional impulsivity

To measure impulsivity, participants responded to Dickman’s 23-item measure of functional (11 items) and dysfunctional impulsivity (12 items) inventory using a True/False response scale46. The author of the measure provides evidence of good reliability (α = 0.83—0.86) and validity.

Reinforcement sensitivity theory of personality questionnaire

To measure reinforcement sensitivity, participants completed the 65-item Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory of Personality Questionnaire (RST-PQ)45, which comprises six factors: 2 defensive factors, fight-flight-freeze system, and the behavioral inhibition system (BIS); and four behavioral approach system (BAS) factors (Reward Interest, Goal-Drive Persistence, Reward Reactivity, and Impulsivity). The authors of the measure provide evidence of acceptable to strong reliability (α = 0.74—0.93) and validity.

Results

Descriptives

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations are presented in Table 7. All scales demonstrated acceptable internal consistency (α > 0.70). Pairwise deletion was used to maximize sample size for the analyses conducted.

Among the Dark Tetrad traits, the same pattern and magnitude of intercorrelations observed in the other three studies replicated. Additionally, Dark Tetrad traits were positively correlated with positive urgency and negative urgency, which reflect emotion-driven impulsivity, as well as impulsivity from the RST-PQ, and dysfunctional impulsivity. However, the strength of those correlations ranged from weak to moderate suggesting that difficulties in emotion regulation might be a shared characteristic among the Dark Tetrad traits; however, the variability in correlations affords an opportunity to distinguish these traits. Each Dark Tetrad trait was also significantly correlated with the resource and complexity subscales of the MDS, although these correlations were small.

Difference tests for correlations

Compared to both Machiavellianism and sadism, psychopathy had significantly stronger relationships with positive urgency, premeditation, sensation-seeking, functional Impulsivity, dysfunctional impulsivity, impulsivity, flight-fight-freeze system, and Behavioural Activation System – Reward Interest (see Table 8). Psychopathy had a stronger relationship with negative urgency than Machiavellianism, but not sadism. Psychopathy also had significantly weaker relationships with scores on the behavioral inhibition system subscale of the RST-PQ than either Machiavellianism or sadism. Finally, no significant differences in correlations were observed for any of the MDS scales, for perseverance (UPPS-P) or for Goal-Drive Persistence and Reward Reactivity on the RST-PQ.

General discussion

The purpose of these studies was to clarify the presumptive redundancy of psychopathy and Machiavellianism, as well as psychopathy and sadism, using narrow bandwidth traits. A summary of observed differences can be found in Table 9. These four studies extend the current research on the putative redundancy of the Dark Tetrad traits by addressing and moving toward the resolution of the ongoing debate on this matter. Some researchers posit that the traits are redundant due to their common features such as callousness and manipulation15. However, the traits do vary in their associations with lower-level traits1,12, as well as behavioral outcomes21. This study expanded the work conducted by Kowalski et al.12 and contributed to the redundancy debate between psychopathy and Machiavellianism, as well as psychopathy and sadism, by demonstrating that these traits differ significantly in their relation to various narrowband traits.

Psychopathy vs. machiavellianism

Overall, the studies provide substantial evidence for the differentiation between psychopathy and Machiavellianism, as currently measured. In Study 1, this manifested in significant differences in correlations with conventionality, seductiveness, manipulativeness, humorousness, integrity, femininity, religiosity, and egotism, ranging from small to moderate differences. Of these traits, there is theoretical emphasis in the Machiavellianism literature placed on a lack of conventionality (i.e., desires to maintain customs and traditions) and religiosity. For example, Christie and Geis characterize Machiavellianism as including interpersonal coldness because of a lack of conventional morality7. Similarly, Machiavelli posited that, “…it is well to seem merciful, faithful, humane, sincere, religious, and also to be so; but you must have the mind so disposed that when it is needful to be otherwise you may be able to change to the opposite qualities…to act against faith, against charity, against humanity, and against religion…to do evil if constrained.”8 Hence, Machiavellianism does not emphasize a lack of religiosity, but rather a flexible and morally pragmatic approach to religion. The stronger relationship between psychopathy and risk-taking is not surprising, as psychopathy is theoretically characterized by impulsivity5.

In Study 2, we observed significant differences between correlations with nine of 25 HEXACO facets: fearfulness, anxiety, social self-esteem, social boldness, sociability, liveliness, perfectionism, prudence, and creativity. Of these, anxiety and fear are theoretically tied to psychopathy. In Cleckley’s characterization of psychopathy4, ‘lack of nervousness’ was a salient feature of psychopathy (though this has been disputed by some)117. Some theoretical conceptualizations of psychopathy have emphasized a lack of fear118, and some research has supported this position119,120. Prudence (i.e., tendency to deliberate carefully and to inhibit impulses) is inherent in descriptions of Machiavellianism. Thus, the finding that Machiavellianism was more strongly correlated with this facet is consistent with theory; however, we observed that Machiavellianism was negatively and weakly correlated with prudence, which lends some credence to criticisms that the MACH-IV does not measure Machiavellianism consistently with theory121,122. Based on our data, the claim that MACH-IV Machiavellianism and psychopathy are virtually indistinguishable25,123 seems to be exaggerated.

Study 3 revealed that Machiavellianism differed from psychopathy in its relationship with both proactive and reactive regression with small effect sizes and 12 of 25 PID-5 facets. The differences observed for correlations with anxiousness, impulsivity, and risk-taking are consistent with theoretical descriptions of the traits. The differences in relations with anxiousness and risk-taking also replicates the findings from Studies 1 and 2 (using different measures).

In Study 4, we investigated differences between correlations with impulsivity, approach and avoidance (RST), and MDT in order to target traits that differentiate Machiavellianism and psychopathy on theoretical grounds. Machiavellianism differed from psychopathy in relationships with positive urgency, negative urgency, premeditation, and sensation-seeking (all small effects except for sensation-seeking), but not perseverance. The dark traits also differed in their relationships with both functional and dysfunctional impulsivity, with psychopathy more strongly correlated with both functional and dysfunctional impulsivity (medium and small effects, respectively). Surprisingly, psychopathy and Machiavellianism did not differ in their correlations with any of the MDT variables, which is contrary to theoretical expectations47 and results of previous empirical research that have presented seemingly contrary results113,124. The lack of differences found between Machiavellianism and psychopathy on the MDS could be related to the validity of the MACH-IV. This scale does not perform as well as other Machiavellianism scales when assessing certain differences between Machiavellianism and psychopathy14. It is possible that the MACH-IV does not fully capture the nuances of the Machiavellianism trait in relation to deception. This is consistent with results from work by de Roos and Jones114, which used several different measures of both Machiavellianism and psychopathy to investigate the correlations between the two traits and the MDS. The authors found that, for all Machiavellianism measures except the MACH-IV, the relationship between Machiavellianism and MDS was stronger than the relationship between psychopathy and MDS. These findings suggest that individuals high in Machiavellianism, compared to those high in psychopathy. are more likely to orient themselves towards long-term deception strategies and behaviors.

Finally, we found that Machiavellianism and psychopathy differed in terms of their relations with RST-PQ Impulsivity, fight-flight-freeze system, BIS, and reward interest (small effects except for impulsivity, which showed a medium effect), but not goal-drive persistence or reward reactivity. These results are aligned with theory, as psychopathy is linked theoretically to impulsivity, lack of fear (fight-fright-freeze represents a fear system)117, and lack of anxiety (BIS represents an anxiety system4). Empirical research has implicated the BIS in employing cognitive strategies related to risk assessment and attentional scanning to reduce the chance of negative consequences125.

Overall, our studies provide substantial evidence that psychopathy and Machiavellianism, as currently measured, have overlap, but also differ meaningfully. This is not to say that attempts at improving the measurement of Machiavellianism in order to optimize discriminant validity126,127 have been in vain, as there is some evidence that the MACH-IV is not as true to theoretical accounts of Machiavellianism (for example, as evident in the negative correlation with HEXACO prudence). Therefore, these new measures are welcome and should be thoroughly tested for reliability and validity. Still, considering our findings, claims that Machiavellianism (as measured by the MACH-IV) and psychopathy are indistinguishable25 cannot be upheld. Overlapping variance with Honesty-Humility is often central to arguments that these traits are redundant55, and as previously mentioned, is often considered the core of the Dark Tetrad, especially when contrasted against other broad personality dimensions. Yet, at the facet level for Honesty-Humility, we observed differences between sadism and psychopathy (i.e., fairness, sincerity). The pattern of differences observed across our studies suggest that, in contrast to sadism and Machiavellianism, psychopathy distinguishes itself from both dark traits as more interpersonally manipulative (i.e., traits related to manipulativeness, seductiveness, and deceptiveness), more dominant (i.e., traits related to social boldness, lack of submissiveness), more emotionally reactive (i.e., impulsivity, reactive aggression), more adventurous (i.e., traits relating to non-conformity, fearlessness, sensation-seeking, and risk-taking), and more emotionally detached (i.e., traits related to callousness and emotional distance from others). Through conducting this research, we aimed to shed light on how making distinctions should be investigated at a narrower trait level to disentangle psychopathy from the other Dark Tetrad traits.

Psychopathy and sadism

Recently, researchers have questioned the putative redundancy between psychopathy and sadism60,128. Although Dinić et al. concluded that elements of sadism can be distinguished from psychopathy60, Blötner and Mokros suggested that psychopathy and sadism demonstrated overlap in terms of their nomological networks32. Given the inconsistencies across studies in terms of the overlap between the two traits, we sought to clarify the distinctions between the two traits by assessing their relationships with narrowband constructs. First, we found that of the SPI traits, psychopathy was more strongly related to humorousness, seductiveness, manipulativeness, (low) femininity, egotism, and risk-taking. When the HEXACO model was examined, we found that compared to sadism, psychopathy had significantly stronger relationships with fairness and sincerity, indicating that those scoring higher in psychopathy may be somewhat more likely to exhibit a lack of humility. Psychopathy was also more strongly and negatively tied to all facets of Emotionality, as well as all facets of Conscientiousness except for diligence. Among the PID scales, psychopathy had significantly stronger correlations with (low) anxiousness, deceitfulness, manipulativeness, risk-taking, (low) submissiveness, and restricted affectivity. Overall, these differences in associations are perplexing, as psychopathy and sadism share callous manipulative and aggressive features129, as well as features related to low Emotionality and Conscientiousness6. However, Dinić et al. concluded that psychopathy represents the most central feature of the Dark Tetrad, such that its importance in the topology of the network is the strongest, but also concluded that psychopathy was not redundant with sadism, as reflected by the clustering coefficients, possibly explaining the stronger associations between psychopathy and these traits in the present studies60.

We found that sadism was more strongly and positively associated with reactive aggression than psychopathy. Although psychopathy and sadism are both related to aggression and violence, psychopathy tends to be more strongly tied to instrumental forms of aggression in which individuals engage in violent behaviors to achieve a particular goal, such as control over one’s partner130. Sadism was also more strongly correlated with PID-5 hostility and separation insecurity than psychopathy. The primary feature of sadism concerns their engagement in aggressive and hostile behaviors for pleasure131; thus, the stronger association with hostility is unsurprising. However, the links between sadism, psychopathy, and separation insecurity (i.e., a feature of borderline personality disorder) are more difficult to explain. Psychopathy and separation insecurity were non-significantly correlated, and the effect size for the link between sadism and separation insecurity was small. Thus, this association may have been a statistical artifact influenced by, for example, a large sample size.

Regarding impulsivity, we found that psychopathy was more strongly related to positive urgency, premeditation, sensation-seeking, functional impulsivity, and dysfunctional impulsivity. Although we did not formulate explicit hypotheses regarding the differentiation of impulsivity between psychopathy and sadism, our results align with the robust conceptual associations linking psychopathy and impulsive tendencies114. On the other hand, although impulsivity may be a feature related to sadism, it is not a defining characteristic of the construct. Lastly, psychopathy was more strongly correlated with behavioral approach system, reflecting an approach orientation towards behaviors that will be rewarded132. This correlation may reflect the strong tendency for those high in psychopathy to engage in impulsive behaviors to help them to attain a specific goal114. Lastly, and somewhat surprisingly, psychopathy was non-significantly related to the behavioral inhibition system, whereas sadism showed a small positive correlation. This contrasts past findings indicating that individuals scoring high in sadism are likely to aggress against others regardless of negative consequences59. Again, however, the effect size was small for sadism; thus, it is plausible that this was a statistical artifact due to a large sample size.

Despite many significant differences in the magnitude of correlations across the four studies, there were some subscales for which fewer significant differences were found. For example, there were no significant differences observed between Machiavellianism and psychopathy in terms of their correlations with Honesty-Humility, thriftiness, and rigid perfectionism (among others). For sadism and psychopathy, there were no significant differences in correlations with, for example, conventionality, religiosity, thriftiness, integrity, and Agreeableness, among others. These non-differences align with theoretical conceptualizations of each construct. For instance, low Agreeableness is central to each of the Dark Tetrad traits133, reflecting their lack of cooperation and forgiveness, as well as high anger and criticalness. Similarly, Honesty-Humility is considered a driving feature underlying each of the traits134. Given that these personality dimensions are strongly related to each Dark Tetrad traits, both theoretically and empirically, it is unsurprising that there were no differences in the magnitude of these correlations across the traits. Other constructs, such as thriftiness and rigid perfectionism (among others), were empirically unrelated to any of the Dark Tetrad traits in the current study, as well as theoretically unrelated. For example, thriftiness, defined by not expending resources unless necessary37, is not conceptually relevant to features of the Dark Tetrad. Thus, it is again unsurprising that the magnitudes of these correlations were not significantly different.

Limitations and future directions

A limitation of this research is that the data used in the four studies were collected from undergraduate psychology students at a single North American university. Using data from an exclusively student sample may have artificially limited the generalizability of the study. Future researchers looking to build and expand on our findings should consider using a broader and more diverse population, with the aims of producing even more generalizable findings.

Our four studies also exclusively relied on single-timepoint, self-report ratings of personality, which may have attenuated the relationships among our variables of interest135. Future researchers may consider using observer-reports or multiple time-point studies136 to examine the effects of the phenomenon we investigated from different perspectives or over time.

Another limitation that may have had implications for the results of our study was the wide range in Cronbach’s alphas produced by the scales used. Across the four studies, most of the measures used had sufficient or excellent levels of reliability (0.60 to 0.93)137. However, analyses involving scales that had reliability values on the lower end of sufficient may have limited the accuracy of reported results. This may have been especially true for some of the comparisons conducted in Study 2, where one subscale (unconventionality) from the Openness to Experience factor in the HEXCO measure and one of the composite subscales commonly computed using the HEXACO measure (altruism) demonstrated less-than-acceptable levels of reliability. Consequently, future researchers interested in the specific relationship between two scales with suboptimal reliability may consider using longer-format versions of the measures where available.

Finally, our conclusions are limited by a lack of standardized metric by which to determine whether there was sufficient evidence of differential validity between the constructs of interest. That is, our ability to claim that there was, or was not, overlap between any of the constructs of interests was limited to commenting on the magnitude of the difference in correlation between two constructs of interests and a target scale. However, there is no agreed upon magnitude of overlap or non-overlap that could be used to base an assertion of whether there is indeed evidence differential validity amongst the constructs.

Consequently, it is essential that future researchers interested in studying this issue of disentanglement amongst the Dark Tetrad traits not only replicate the findings of our work, but also move beyond comparisons of trait scores. That is, we encourage future researchers to employ experimental methods to examine cognitive, affective, and most importantly behavioral outcomes to help elucidate the differences between the traits of interest. Although the value of this work is mostly theoretical in nature, by attempting to replicate the findings of our work using behavioral outcomes we may identify interesting and useful real-world applications of this work. Two specific avenues for future research we think may be particularly fruitful would be examining shared patterns across interpersonal relationships (romantic or otherwise)138,139,140, workplace behaviors141, and career interests142,143. Not only will this allow us to examine potential real-world consequences of these potential overlaps, but it would also serve as opportunities to replicate our work from a trait perspective, collectively building towards support for our current findings that the Dark Tetrad traits are, indeed, distinct in nature.

Concluding remarks

Overall, our findings regarding the potential overlap between psychopathy and sadism run contrary to the work by Blötner et al.32, as we observed significant differences between sadism and psychopathy in their relationships with relevant narrowband traits. Based on the results of the present study, and in line with work by other researchers20, we assert that the two dark traits are not redundant and cannot be simplified to a single construct.

Similarly, with respect to psychopathy and Machiavellianism, our findings support the notion that these are related but distinct constructs. Pursuant to efforts to refine the measurement of Machiavellianism, our findings once again suggest that Machiavellianism (as measured by the MACH-IV) and psychopathy are not redundant construct, and therefore cannot be simplified into a single construct.

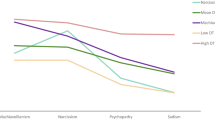

Note: HEXACO dimensions that were significantly differentially correlated amongst psychopathy and Machiavellianism are omitted here if the effect size did not meet the threshold for a small effect.

Data availability

All four datasets are available and can be accessed on OSF: https://osf.io/b789h/?view_only=231ad1f9f88d413198a911696fe5cd55.

References

Paulhus, D. & Williams, K. M. The dark triad of personality: Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy. J. Res. Pers. 36, 556–563. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(02)00505-6 (2002).

Raskin, R. N. & Hall, C. S. A narcissistic personality inventory. Psychol. Rep. 45(2), 590. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1979.45.2.590 (1979).

Emmons, R. A. Narcissism: Theory and measurement. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 52(1), 11–17. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.52.1.11 (1987).

Cleckley, H. The Mask of Sanity (St. Louis, 1982).

Lilienfeld, S. O. Methodological advances and developments in the assessment of psychopathy. Behav. Res. Ther. 36(1), 99–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(97)10021-3 (1998).

Plouffe, R. A., Smith, M. M. & Saklofske, D. H. A psychometric investigation of the Assessment of Sadistic Personality. Personality Individ. Differ. 140, 57–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.01.002 (2019).

Christie, R. & Geis, F. L. Machiavellianism (Academic Press, 1970).

Machiavelli, N. The Prince. (New American, 1513/1981)

Jones, D. N. & Figueredo, A. J. The core of darkness: Uncovering the heart of the Dark Triad. Eur. J. Pers. 27(6), 521–531. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.1893 (2013).

Chabrol, H., Van Leeuwen, N., Rodgers, R. & Séjourné, N. Contributions of psychopathic, narcissistic, Machiavellian, and sadistic personality traits to juvenile delinquency. Personality Individ. Differ. 47(7), 734–739. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.06.020 (2009).

Kowalski, C. M., Rogoza, R., Saklofske, D. H. & Schermer, J. A. Dark triads, tetrads, tents, and cores: Why navigate (research) the jungle of dark personality models without a compass (criterion)? Acta Physiol. (Oxf) 221, 103455. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2021.103455 (2021).

Kowalski, C. M., Vernon, P. A. & Schermer, J. A. The dark triad and facets of personality. Curr. Psychol. 40, 5547–5558. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00518-0 (2021).

O’Boyle, E. H., Forsyth, D. R., Banks, G. C., Story, P. A. & White, C. D. A meta-analytic test of redundancy and relative importance of the Dark Triad and Five-Factor Model of personality. J. Personality 83(6), 644–664. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12126 (2015).

Vize, C. E., Lynam, D. R., Miller, J. D. & Collison, K. L. Differences among Dark Triad components: A meta-analytic investigation. Personality Disorders 9(2), 101–111. https://doi.org/10.1037/per0000222 (2018).

Bonfá-Araujo, B., Lima-Costa, A. R., Hauck-Filho, N. & Jonason, P. K. Considering sadism in the shadow of the Dark Triad Traits: A meta-analytic review of the Dark Tetrad. Personality Individ. Differ. 197, 111767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2022.111767 (2022).

Kowalski, C. M., Di Pierro, R., Plouffe, R. A., Rogoza, R. & Saklofske, D. H. Enthusiastic acts of evil: The Assessment of Sadistic Personality in Polish and Italian populations. J. Personality Assess. 102(6), 770–780. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2019.1673760 (2020).

Karandikar, S., Kapoor, H., Fernandes, S. & Jonason, P. K. Predicting moral decision-making with dark personalities and moral values. Personality Individ. Differ. 140, 70–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.03.048 (2019).

Ritchie, M. B., Blais, J. & Forth, A. E. “Evil” intentions: Examining the relationship between the Dark Tetrad and victim selection based on nonverbal gait cues. Personality Individ. Differ. 138, 126–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.09.013 (2019).

Pajevic, M., Vukosavljevic-Gvozden, T., Stevanovic, N. & Neumann, C. S. The relationship between the Dark Tetrad and a two-dimensional view of empathy. Personality Individ. Differ. 123, 125–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.11.009 (2018).

Johnson, L. K., Plouffe, R. A. & Saklofske, D. H. Subclinical sadism and the Dark Triad: Should there be a Dark Tetrad? J. Individ. Differ. 40(3), 127–133. https://doi.org/10.1027/1614-0001/a000284 (2019).

Jones, D. N. & Weiser, D. A. Differential infidelity patterns among the Dark Triad. Personality Individ. Differ. 57, 20–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.09.007 (2014).

Vernon, P. A., Villani, V. C., Vickers, L. C. & Harris, J. A. A behavioral genetic investigation of the Dark Triad and the Big 5. Personality Individ. Differ. 44(2), 445–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2007.09.007 (2008).

Jones, D. N. Risk in the face of retribution: Psychopathic individuals persist in financial misbehavior among the Dark Triad. Personality Individ. Differ. 67, 109–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.01.030 (2014).

Jones, D. N. & Paulhus, D. L. Duplicity among the Dark Triad: Three faces of deceit. J. Personality Soc. Psychol. 113, 349–342. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000139 (2017).

McHoskey, J. W., Worzel, W. & Szyarto, C. Machiavellianism and psychopathy. J. Personality Soc. Psychol. 74(1), 192–210. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.1.192 (1998).

Muris, P., Merckelbach, H., Otgaar, H. & Meijer, E. The malevolent side of human nature: A meta-analysis and critical review of the literature on the Dark Triad (narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy). Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 12(2), 183–204. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691616666070 (2017).

Malesza, M. & Ostaszewski, P. Dark side of impulsivity–Associations between the Dark Triad, self-report and behavioral measures of impulsivity. Personality Individ. Differ. 88, 197–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.09.016 (2016).

Reynolds, B., Ortengren, A., Richards, J. B. & de Wit, H. Dimensions of impulsive behavior. Personality Individ. Differ. 40, 305–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2005.03.024 (2006).

Sleep, C. E., Lynam, D. R., Hyatt, C. S. & Miller, J. D. Perils of partialing redux: The case of the Dark Triad. J. Abnormal Psychol. 126(7), 939–950 (2017).

Kowalski, C. M. et al. The Dark Triad traits and intelligence: Machiavellians are bright, and narcissists and psychopaths are ordinary. Personality Individ. Differ. 135, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.06.049 (2018).

Miller, J. D., Vize, C., Crowe, M. L. & Lynam, D. R. A critical appraisal of the Dark Triad literature and suggestions for moving forward. Curr. Direct. Psychol. Sci. 23(4), 353–360. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721419838233 (2019).

Blötner, C. & Mokros, A. The next distinction without a difference: Do psychopathy and sadism scales assess the same construct? Personality Individ. Differ. 205, 112102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2023.112102 (2023).

Paunonen, S. V., Haddock, G., Forsterling, F. & Keinonen, M. Broad versus narrow personality measures and the prediction of behavior across cultures. Eur. J. Personality 17(6), 413–433. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.496 (2003).

Jones, D. N. & Mueller, S. M. Is Machiavellianism dead or dormant? The perils of researching a secretive construct. J. Bus. Ethics 176, 535–549. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04708-w (2022).

Paunonen, S. V., Rothstein, M. G. & Jackson, D. N. Narrow reasoning about the use of broad personality measures for personnel selection. J. Organ. Behav. 20, 389–405 (1999).

Elleman, L. G., Condon, D. M., Holtzman, N. S., Allen, V. R. & Revelle, W. Smaller is better: Associations between personality and demographics are improved by examining narrower traits and regions. Collabra Psychol. 6(1), 17210. https://doi.org/10.1525/collabra.17210 (2020).

Paunonen, S. V. & Ashton, M. C. Big Five factors and facets and the prediction of behavior. J. Personality Soc. Psychol. 81(3), 524–539. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.81.3.524 (2001).

Hogan, J. & Roberts, B. W. Issues and non-issues in the fidelity-bandwidth trade-off. J. Organ. Behav. 17, 627–637 (1996).

McAbee, S. T., Oswald, F. L. & Connelly, B. S. Bifactor models of personality and college student performance: A broad versus narrow view. Eur. J. Personality 28, 604–619. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.1975 (2014).

Paunonen, S. V. (2002). Design and Construction of the Supernumerary Personality Inventory. (Research Bulletin 763). University of Western Ontario.

Ashton, M. C. & Lee, K. Empirical, theoretical, and practical advantages of the HEXACO model of personality structure. Personality Soc. Psychol. Rev. 11(2), 150–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868306294907 (2007).

Krueger, R. F., Derringer, J., Markon, K. E., Watson, D. & Skodol, A. E. Initial construction of a maladaptive personality trait model and inventory for DSM-5. Psychol. Med. 42(9), 1879–1890. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291711002674 (2011).

Raine, A. et al. The reactive-proactive aggression questionnaire: Differential correlates of reactive and proactive aggression in adolescent boys. Aggress. Behav. 32(2), 159–171. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20115 (2006).

Cyders, M. A. et al. Integration of impulsivity and positive mood to predict risky behavior: Development and validation of a measure of positive urgency. Psychol. Assess. 19(1), 107–118. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.19.1.107 (2007).

Corr, P. J. & Cooper, A. J. The reinforcement sensitivity theory of personality questionnaire (RST-PQ): Development and validation. Psychol. Assess. 28(11), 1427–1440. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000273 (2016).

Dickman, S. J. Functional and dysfunctional impulsivity: Personality and cognitive correlates. J. Personality Soc. Psychol. 58(1), 95–102. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.58.1.95 (1990).

Jones, D. N. Predatory personalities as behavioral mimics and parasites: Mimicry-Deception Theory. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 9, 445–451. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691614535936 (2014).

Lee, & Ashton, M. C.,. Psychometric properties of the HEXACO-100. Assessment 25(5), 543–556. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191116659134 (2018).

Paunonen, S. V. & Jackson, D. N. What is beyond the Big Five? J. Personality 66(4), 821–835. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.00022 (2000).

Hong, R. Y., Koh, S. & Paunonen, S. V. Supernumerary personality traits beyond the Big Five: Predicting materialism and unethical behavior. Personality Individ. Differ. 53(5), 710–715. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.05.030 (2012).

Veselka, L., Schermer, J. & Vernon, P. A. Beyond the Big Five: The Dark Triad and the Supernumerary Personality Inventory. Twin Res. Hum. Genet. 14(2), 158–168. https://doi.org/10.1375/twin.14.2.158 (2011).

Ashton, M. C., Jackson, D. N., Paunonen, S. V., Helmes, E. & Rothstein, M. G. The criterion validity of broad factor scales versus specific facet scales. J. Res. Personality 29(4), 432–442. https://doi.org/10.1006/jrpe.1995.1025 (1995).

Kowalski, C. M., Simpson, B. & Schermer, J. A. Predicting donation behavior with the Supernumerary Personality Inventory. Personality Individ. Differ. 168, 110319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110319 (2021).

Simpson, B., Maguire, M. & Schermer, J. A. Predicting pro-environmental values and behaviors with the Supernumerary Personality Inventory and hope. Personality Individ. Differ. 181, 111051. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.111051 (2021).

Lee, K., Ogunfowora, B. & Ashton, M. C. Personality Traits Beyond the Big Five: Are They Within the HEXACO Space? J. Personality 73(5), 1437–1463. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00354.x (2005).