Abstract

Monolayer materials typically display intriguing temperature-dependent dielectric and optical properties, which are crucial for improving the structure and functionality of associated devices. Due to its unique photoelectric capabilities, monolayer WSe2 has recently received a lot of attention in the fields of atomically thin electronics and optoelectronics. In this work, we focus on the evolution of the temperature-dependent dielectric function (ε = ε1 + i ε2) of monolayer WSe2 over energies from 0.74 to 6.40 eV and temperatures from 40 to 350 K. We analyze the second derivatives of ε with respect to energy to accurately locate the critical points (CP). The dependence of the observed CP energies on temperature is consistent with the alternative domination of the declining exciton binding energy as the temperature increases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

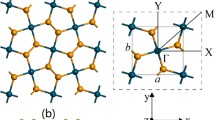

Due to its unique photoelectric properties1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8, including layer-modulated bandgaps, moderate mobility2, a high on–off ratio9, and a noticeable spin–orbit coupling effect1, the monolayer WSe2, a two-dimensional transition-metal dichalcogenide (2D-TMDC) has recently garnered significant interest in the fields of atomically thin electronics and optoelectronics10,11,12,13. The low dimensional materials have strong Coulomb interaction by reducing dielectric screening and confining electron motion spatially, leading to the formation of highly stable, tightly bound electron–hole pairs known as excitons, characterized by substantial binding energy14,15. The utilization of monolayer WSe2, whether in its intrinsic form or as part of tailored heterostructures hybridized with other materials, substantially enhances the performance of related optoelectronic devices and imparts a range of unique features to them9. The intrinsic optical and dielectric properties of monolayer WSe2, typically described by the dielectric function or the complex refractive index16,17, exert a strong influence on the performance of these optoelectronic devices. Moreover, these properties often exhibit distinct layer-dependent behavior. Therefore, it is important to thoroughly investigate the dielectric function of WSe2 at various temperatures in order to elucidate the underlying physical mechanisms that allow these innovative devices to be created and enhanced.

Photoluminescence (PL)8, raman18,19, reflection20,21, transmission, and absorption spectroscopies are the principal experimental methods used to investigate the optical characteristics of monolayer WSe2. These methods provide valuable physicochemical data, such as optical bandgap and absorption properties, however, these measurements depend on sample surface quality and instrumentations therefore we can see spread in reported data21. Also, quantity like refractive index (n) is obtained mathematically from absorption data via Kramers–Kronig (KK) relation means experimental errors cannot be accessed affecting reliability of the measured data. Spectroscopic ellipsometry (SE) is well known as a powerful optical technique to measure the real (ε1) and imaginary (ε2) parts of dielectric function (ε = ε1 + i ε2) of materials independently without using KK transformation providing the way to judge measured data22,23. As a result, Diware et al.24 were able to see Rydberg exciton series even at room temperature using SE. In Ref.21, they studied systematically on the temperature dependence of the dielectric function of WSe2 monolayers. However, the reflection data and KK relations were used to calculate the dielectric function.

In this report, broad-band temperature-dependent optical properties of WSe2 monolayer are measured and analyzed in detail to elucidate the underlaying physical mechanism. A systematic method based on critical point (CP) analysis using the second derivative method is used to extract the characteristics of the optical transitions. We observed eight CPs at room temperature within measured energy range and were able to resolve fourteen CPs at low temperatures due to reduced electron–phonon interaction.

Experiment details and data analysis

Sample characterization

The WSe2 monolayer sample used in this study was obtained from 2D Semiconductor Inc., which was grown by low pressure chemical vapor deposition over c-cut sapphire substrate25. Deposited monolayer shows complete coverage over substrate. Even though quality of the sample was insured by the sample provider, we confirm the quality by Raman spectroscopy and atomic force microscopy (AFM) prior to SE measurements, as shown in Fig. S1 in the supplementary. Due to complete coverage of the monolayer film, we could not find the natural area to measure accurate thickness using normal AFM. Therefore, automated AFM with hard cantilever tip NM-RC from Park Systems Co. was used to make sharp boundary to measure accurate thickness. As shown in Fig. S1a, part of the WSe2 monolayer was removed in the form of 2 × 2 μm2 with a tip hardness of 350 N/m and set-point force of 0.2 V. The resulting AFM micrograph shows the WSe2 thin film surface with grain boundary and a scratch area. The WSe2 thin film thickness is 0.77 nm which suggest it is a monolayer. Raman spectra of WSe2 monolayer was measured using 541 nm laser excitation with 1 mW power. Two characteristic phonon modes, \(E_{2g}^{1}\) (in-plane) and A1g (out-plane) were observed. The separation between these phonon modes is about 9/cm and intensity ration is about 2.0, which are the characteristics of the WSe2 monolayer.

SE measurements

The experimental configuration used in this work is well described in our previous work26. Briefly, the sample was mounted on the cold figure where low temperature is achieved by close-cycle refrigeration. A cold environment was created inside a chamber which was maintained at a pressure of 10–8 Torr to avoid unnecessary condensation. Also, the cold chamber was fitted with stress-free fused-quartz window to avoid noise from optical window. A commercial dual-rotating-compensator type (model RC2, J. A. Woollam Co., Inc. at the Multi dimension material convergence research center of Kyung Hee University) ellipsometer is used in this study. The angle of incidence (AOI) is fixed at 68.2°. Dielectric function spectra in the energy range of 0.74 to 6.40 eV were acquired for temperatures from 40 to 350 K. Additionally, SE data at variable AOI of 60°, 65°, and 70° for WSe2 and sapphire substrate were pre-measured to avoid fitting correlations, as shown in Fig. S2.

Determination of dielectric function of WSe2

As measured SE data is called as the pseudo-dielectric function 〈ɛ〉 which contains all the information coming from penetration depth of a probing light beam, so generally surface roughness and substrate effects are included in <ɛ>. In this work, data were analyzed using a three-phase optical model consisting of the ambient, the WSe2 monolayer, and the sapphire substrate. The thickness of WSe2 was determined by applying the Cauchy model to the data in the transparent region between 0.74 and 1.5 eV, and the yielded thickness is 0.75 nm, agrees well with our AFM measurement, see Fig. S1a–c, and literature19,27,28,29. As seen from AFM measurements in Fig. S1, WSe2 monolayer surface is atomically smooth and uniform, so no need to use a surface-roughness layer in data fitting, which reduces the fitting parameters. Therefore, by fixing the ɛ of sapphire and the thickness of the WSe2 monolayer, the real and imaginary parts of dielectric function of WSe2 are concurrently determined at each wavelength using point-by-point fitting.

The critical-point-energy method

To better resolve the overlapping CP structures, second derivative spectra \(\frac{{d^{2} \varepsilon }}{{dE^{2} }}\) were obtained using the maximum-entropy method of differentiation with appropriate smoothing30. CP parameters were extracted using the standard analytic CP expression31

where a CP is represented by the amplitude A, threshold energy Eg, broadening Γ, and phase ϕ, all treated as adjustable parameters. The exponent n has the values − 1, − 1/2, 0, and + 1/2 for excitonic, 1, 2, and 3D CPs, respectively. We note that the excitonic lineshape has been used widely for TMDC materials, yielding high quality fit to experimental data26,32. For this work, excitonic, 1D, and 2D lineshapes are considered, since 3D is forbidden in 2D materials33.

Result and discussion

Figure 1 shows a comparative analysis of our findings near room temperature, 300 K, (depicted by the black line) in relation to previously documented data. To improve clarity, we have limited the displayed data to the 1.25–3.5 eV range. Data above 3.5 eV cannot be compared as previous reports have not investigated this region. Data of Refs.20 and21 obtained via optical reflectance are shown by the red and blue lines, respectively. Notably, the peak positions of the A and B excitons, located at approximately 1.7, 2.15 eV, are well-defined across all spectra, and their amplitudes exhibit relative consistency. This convergence in amplitude strongly supports the accuracy of our data. Our data demonstrates a gradual decline of the ε2 value from the peak A to zero, extending below the optical band gap. This phenomenon is considered a hallmark of exceptional sample and data quality. The intensity of peak A is lower than the previous result. This discrepancy arises because the value immediately preceding peak A in the Ref.20 is smaller than 0. This may be attributed to a potential error in the K-K transform applied to the reflection data. It is expected to be less accurate than the measurement of ε2 achieved by ellipsometry, as implemented here and in Ref.24. Noting that earlier research involving monolayer WSe2 exhibited similar positions of the A and B exciton peaks. As a result, we confidently assert that the SE data presented in this study accurately represents the dielectric-function values of WSe2.

Using the same analytical approach at 300 K, we present the real and imaginary components of the dielectric function for monolayer WSe2 across a temperature range of 40–350 K, as depicted in Fig. 2a and b respectively. It is noteworthy that this spectral range lies well below the fundamental bandgap of sapphire34 (~ 9.0 eV), so the value of the imaginary part of the dielectric function of the substrate is accurately zero, and the real part exhibits minimal variation. Consequently, we adopt a temperature-independent dielectric function for the substrate, a reasonable approximation under these conditions.

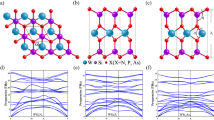

For clarity, the spectra have been offset vertically by increments of 15, and the number of temperature points has been reduced. Within each spectrum we readily discern the presence of 15 CP structures denoted as A, B, E0, C, E0 + Δ0, and E1-9. We observe that these CP structures exhibit blue shifts and enhanced characteristics at lower temperatures. This enhancement facilitates the identification of new, smaller CPs, as it mitigates the impact of the strong thermal noise experienced at room temperature. These observed changes can be elucidated by considering the reduction in electron–phonon interactions and the contraction of lattice constants at lower temperatures.

We highlight the changes in Fig. 3, where a comparison of the imaginary part of the dielectric function for the lowest and highest temperatures are shown. We observe differences in the number of peak displacements. At the highest temperature, Peak E1 is no longer visible, and peaks E4 and E5 cannot be distinguished. The peaks E6, E7, E8, and E9 exhibit similar behavior. It is crucial to note that the qualitative determination of CP energies from the original spectra is challenging due to the pronounced asymmetry of the CP structures, stemming from contributions from transitions across various regions of the Brillouin zone. Therefore, we have employed a standard procedure to determine CP energies at different temperatures, involving the analysis of derivatives.

Figure 4 provides a visual representation of the 2nd derivatives, accompanied by their corresponding best-fit curves. In this figure, open circles denote the 2nd derivatives of measured values for ε1, while the black and red lines represent the best fits for the real and imaginary parts, respectively. To enhance clarity, the second derivatives of the data for ε2 are not shown.

The best fit for \(\frac{{d^{2} \varepsilon_{1} }}{{dE^{2} }}\) (black lines) and \(\frac{{d^{2} \varepsilon_{2} }}{{dE^{2} }}\) (red lines) from (a) 1.5 to 3.6 eV and (b) 3–6.40 eV. The data at 350 K in (a) is multiplied by two and the data for \(\frac{{d^{2} \varepsilon_{2} }}{{dE^{2} }}\) are not shown for clarity.

To facilitate comprehension, the spectra have been offset, with increments of 12,500 for Fig. 4a and 5000 for Fig. 4b. As temperature decreases, a clear blue shift in the CP energies becomes evident. At 40 K, the CP structures exhibit significantly sharper characteristics than those at higher temperatures, thereby unveiling the presence of new CPs in region above 3.6 eV. In Fig. 4a, a distinctive pattern emerges within the exciton A region. We note that the A- trion consistently exhibits a higher dominance compared to the A exciton. This recurring phenomenon aligns closely with the material's intrinsic characteristics as an n-type semiconductor. These observations contribute deeper insights to facilitate the accurate design and development of optoelectronic components and devices based on monolayer WSe2.

Table 1 presents our results for the CP energies at 40 K and 350 K with a band calculations35 and other experimental results obtained by SE as well as results obtained by reflection anisotropy spectroscopy (RAS) and photoluminescence (PL). The results are consistent for the exciton A peaks at both low and room temperatures. The previous PL report does not show the trion A- peak at room temperature. Our results are in good agreement with RAS20 results at low temperatures. In Ref.25, authors observed the Rydberg exciton series even at room temperature SE spectra using the same critical-point-energy method presented here. Consequently, CPs may overlap, leading to variations in energy and other CP parameters. Therefore, we would like to emphasize that the combination of low temperature measurements and critical-point-energy method in this work should extract more reliable and accurate CP parameters. As mentioned, our findings align closely with results obtained using other methods. From the Table 1, we can observe that the CP energy differences between the A-, A, and B excitons at 40 K and 350 K are similar.

This similarity in their energy differences is more clearly illustrated in Fig. 5, which shows CP energy values (represented by dots) acquired through the second-derivative analysis. The fit results are depicted as solid lines, obtained using a phenomenological expression that includes the Bose–Einstein (BE) statistical factor for phonons36,37:

Here, Θ represents the mean frequency of phonons, and EB signifies the interaction strength between electrons and phonons. For other CPs exhibiting negligible curvature in their temperature dependence, we fit a linear equation35,36:

where EL is an adjustable parameter and λ is the temperature coefficient -dE/dT. The best fit parameters are listed in Table 2.

Additionally, we employed a matching procedure with the Manoogian-Woolley (M-W) expression to analyze the band gap behavior38.

Figure 6 shows our experimental data alongside the best fit obtained by using the M-W. The M-W equation offers insights into the temperature dependence of band gap, where E0(0) represents the band gap at 0 K, while the second term, UTx accounts for the lattice dilation. The dynamic component of the energy gap shift in semiconductors is described as V∙θ∙coth(θ/2T), where V is an adjustable parameter, T is temperature, and θ signifies the mean frequency of the total phonon spectrum. The fitting outcomes reveal that E0(0) = 2.523 eV. The derived value of 1.09 for x falls within the range of 0.6–1.2 as documented in the literature39. The determined thermal expansion coefficient, U, is 3.4 × 10–4/K, indicating non-linear expansion, which is in a same order to the linear expansion coefficient of bulk WSe2 along the a-axis, which stands at 6.8 × 10–4/K40. However, discrepancy in the absolute values can be attributed to bulk crystal nature and linear expansion, whereas our results are for monolayer and non-linear expansion. Regarding θ, which signifies the mean frequency of the total phonon spectrum, the fitting yielded a value of θ = 160 K, consistent with the Debye temperature of bulk sample41. Table 3 shows the comparison of the thermal expansion constant of bulk and monolayer WSe2 obtained from the Raman spectroscopy and X-ray diffraction.

In Fig. 6, the behavior of the A‾, A, and B transitions exhibit a similar trend with temperature, providing strong evidence that their origins are similar. The energy difference between A and A‾, referred to as the trion binding energy, and the separation between B and A, representing the spin–orbit splitting at the maximum valence band at the K valley, appear to be temperature-independent, remaining constant at approximately 54 meV and 382 meV, respectively.

Conversely, the temperature dependence of E1, which is fit with a linear equation, introduces some uncertainty due to the relatively small amplitude of the E1 CP, which is evident at only lower temperatures as seen in Fig. 5. This diminished amplitude makes it challenging to accurately detect and fit, leading to the observed uncertainty.

The energy gap between E0 and A, known as the exciton binding energy, is approximately 1.18 eV at 40 K and 1.25 eV at 350 K. This value remains almost constant with temperature, in good agreement with the result reported in previous work6,20,25. It is worth noting that Ref. 11 points out that the overlap between the electronic band gap of monolayer WSe2 and continuous excitonic CPs makes it difficult to observe the fundamental band gap (E0) through conventional absorption spectroscopy, even at cryogenic temperatures. However, we not only observe the E0 band gap as a shoulder-like curvature in the original ε2 spectrum at 40 K but also systematically investigate its temperature dependence to confirm its authenticity as a consistent CP structure. Additionally, at higher energies, the CPs exhibit a smaller redshift with increasing temperature.

Conclusions

This study presents a comprehensive analysis of the temperature dependence of the CP energies of monolayer WSe2 from 40 to 350 K. We focus particularly on the CP energies, which are derived from the analysis of dielectric function spectra obtained through spectroscopic ellipsometry from 0.74 to 6.40 eV. At 350 K, we determined the energies of eleven CPs. Additionally, four more CPs, E1, E4, E6, and E7 were discovered at cryogenic temperatures through the analysis of ε spectra using critical-point-energy method.

Most CPs exhibit a noticeable blue shift and an augmented structural complexity at lower temperatures. This phenomenon can be attributed to the reduction in lattice constant and the diminishing impact of electron–phonon interactions. The temperature dependence of each CP is effectively modeled either through a linear equation or a phenomenological expression featuring the Bose–Einstein statistical factor. At lower temperatures, we distinctly observe the separation of excitons A, B, and trions A‾. The charged exciton peak A‾ dominates the neutral exciton peak A at all temperatures. This behavior aligns with the n-type semiconducting characteristics of the material. In addition to the electronic band gaps, we report exciton and trion binding energies, as well as spin–orbit splitting. These findings provide valuable insights that will facilitate the precise engineering of optoelectronic components and devices based on monolayer WSe2.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Wang, D. et al. Quantum Hall effect measurement of spin-orbit coupling strengths in ultraclean bilayer graphene/WSe2 heterostructures. Nano Lett. 19, 7028–7034. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.9b02445 (2019).

Chen, P. et al. Anisotropic carrier mobility from 2H WSe2. Adv. Mater. 34, 7. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202108615 (2022).

Jin, C. et al. On optical dipole moment and radiative recombination lifetime of excitons in WSe2. Adv. Funct. Mater. 27, 19. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201601741 (2017).

Li, Z. et al. Emerging photoluminescence from the dark-exciton phonon replica in monolayer WSe2. Nat. Commun. 10, 1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10477-6 (2019).

Kim, H. et al. Synthetic WSe2 monolayers with high photoluminescence quantum yield. Sci. Adv. 5, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aax7398 (2019).

Gu, H. et al. Layer-dependent dielectric and optical properties of centimeter-scale 2D WSe2: Evolution from a single layer to few layers. Nanoscale 11, 22762–22771. https://doi.org/10.1039/C9NR04270A (2019).

Zhang, S. et al. Visualizing moiré ferroelectricity via plasmons and nano-photocurrent in graphene/twisted-WSe2 structures. Nat. Commun. 14, 6200. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-41773-x (2023).

Yan, T. et al. Photoluminescence properties and exciton dynamics in monolayer WSe2. Appl. Phys. Lett. 105, 785. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4895471 (2014).

Lu, Z. et al. Electrical characteristics of WSe2 transistor with amorphous BN capping layer. Results Phys. 38, 105568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rinp.2022.105568 (2022).

Manca, M. Study of the optoelectronic properties of atomically thin WSe2. https://theses.hal.science/tel-02879948 (2023).

Jung, D. H. et al. Quantification of Schottky barrier height and contact resistance of a Au electrode on multilayer WSe2. J. Korean Phys. Soc. 80, 307–310. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40042-021-00355-0 (2022).

Fazeli, Y. et al. Unveiling the properties of transition-metal dichalcogenides: A comprehensive study of WTe2, WSe2, ZrTe2, and NiTe2 in bulk and monolayer forms. J. Mater. Sci. 58, 10217–10217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-023-08545-w (2023).

Zheng, H. et al. Exploring the regulatory effect of stacked layers on moiré excitons in twisted WSe2/WSe2/WSe2 homotrilayer. Nano Res. 16, 10573–10579. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12274-023-5822-8 (2023).

Ashwin, R. Large excitonic effects in monolayers of molybdenum and tungsten dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. B 86, 115409 (2012).

He, K. Tightly bound excitons in monolayer WSe2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 026803 (2014).

Kronig, R. L. On the theory of dispersion of X-rays. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 12, 547. https://doi.org/10.1364/JOSA.12.000547 (1926).

Kramers, H. A. Atti del Congresso Internazionali dei Fisic (Springer, 1927).

del Corro, E. et al. Excited excitonic states in 1L, 2L, 3L, and Bulk WSe2 observed by resonant Raman Spectroscopy. ACS Nano 8, 9629–9635. https://doi.org/10.1021/nn504088g (2014).

Pawbake, A. S. et al. Large area chemical vapor deposition of monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides and their temperature dependent Raman Spectroscopy studies. Nanoscale 00, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1039/C5NR07401K (2016).

Lee, S.-Y. et al. Self-consistent dielectric constant determination for monolayer WSe2. Opt. Express 26, 23061. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.26.023061 (2018).

Li, Y. et al. Measurement of the optical dielectric function of monolayer transition-metal dichalcogenides: MoS2, MoSe2, WS2, and WSe2. Phys. Rev. B 90, 205422. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.90.205422 (2014).

Aspnes, D. E. Spectroscopic ellipsometry—a perspective. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A Vacuum Surfaces Film 31, 5. https://doi.org/10.1116/1.4809747 (2013).

Jung, Y. W. et al. Study on TiN film growth mechanism using spectroscopic ellipsometry. J. Korean Phys. Soc. 80, 185–189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40042-021-00395-6 (2022).

Diware, M. S. et al. Dielectric function, critical points, and Rydberg exciton series of WSe2 monolayer. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 30, 235701. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-648X/aac187 (2018).

Manca, M. et al. Enabling valley selective exciton scattering in monolayer WSe2 through upconversion. Nat. Commun. 8, 14927. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14927 (2017).

Park, H. G. et al. Temperature dependence of the critical points of monolayer MoS2 by ellipsometry. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 51, 621–635. https://doi.org/10.1080/05704928.2016.1166436 (2016).

Quereda, J. et al. Single-layer MoS2 roughness and sliding friction quenching by interaction with atomically flat substrates. Appl. Phys. Lett. 105, 5. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4892650 (2014).

Chen, J.-W. et al. A gate-free monolayer WSe2 pn diode. Nat. Commun. 9, 3143. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-05326-x (2018).

Fang, H. et al. High-performance single layered WSe 2 p-FETs with chemically doped contacts. Nano Lett. 12, 3788–3792. https://doi.org/10.1021/nl301702r (2012).

Le, L. V. et al. Maximum-entropy revisited: Optimal filtering of spectra. J. Appl. Phys. 129, 22. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0051602 (2021).

Cardona, M. Modulation Spectroscopy, Suppl. 11 of Solid State Physisc, p 119, (Academic, New York, 1969).

Zhan, Q. Q. et al. Two-photon luminescence and second harmonic generation of single layer molybdenum disulphide nanoprobe for nonbleaching and nonblinking optical bioimaging. Prog. Electromagn. Res. 166, 107–117. https://doi.org/10.2528/PIER19072502 (2019).

Park, H. G. et al. Temperature dependence of the dielectric function of monolayer MoSe2. Sci. Rep. 8, 3173. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-21508-5 (2018).

Liu, H.-L. et al. Optical properties of monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides probed by spectroscopic ellipsometry. Appl. Phys. Lett. 105, 20. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4901836 (2014).

Sahin, H. et al. Computing optical properties of ultra-thin crystals. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 6, 351 (2016).

Jung-Kim, T. et al. Temperature dependence of the dielectric functions and the critical points of InSb by spectroscopic ellipsometry from 31 to 675 K. J. Appl. Phys. 114, 10. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4820765 (2013).

Lautenschlager, P. et al. Temperature dependence of the interband critical-point parameters of InP. Phys. Rev. B 36, 4813–4820. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.36.4813 (1987).

Manoogian, A. et al. Temperature dependence of the energy gap in semiconductors. Can. J. Phys. C 62, 285 (1984).

Lárez, C. et al. Alloy composition and temperature dependence of the direct energy gap in AlxGa1 −xAs. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 58, 1111 (1997).

Bhatt, S. V. et al. Raman spectroscopic investigations ontransition-metal dichalcogenides MX2(M=Mo, W; X=S, Se) at high pressures and low temperature. J. Raman Spectrosc. 45, 971 (2014).

Mathew, S. et al. Temperature dependent structural evolution of WSe2: A synchrotron X-ray diffraction study. Condens. Matter 5, 76 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIP) (NRF- 2021R1A2C1005359 and NRF- 2020R1A5A1016518).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.X.A. conceived the major part of the SE experiments. N.X.A., M.S.D., T.J.K.*, and Y.D.K.* analyzed SE data and prepared the manuscript. L.V.L. performed data filtering. S.K and Y.D.K analyzed Raman data.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nguyen, X.A., Le, L.V., Kim, S.H. et al. Temperature dependence of the dielectric function and critical points of monolayer WSe2. Sci Rep 14, 13486 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-64303-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-64303-1

- Springer Nature Limited