Abstract

This study in older hospitalized patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) aimed to examine the prevalence of beta-blocker prescription and its associated factors. A total of 190 participants were recruited from July 2019 to July 2020. The inclusion criteria included: (1) aged ≥ 60 years, (2) having a diagnosis of chronic HFrEF in the medical records, (3) hospitalized for at least 48 h. The participants had a mean age of 75.5 ± 9.1, and 46.8% were female. Of these, 55.3% were prescribed beta-blockers during admission. To explore the factors associated with beta-blocker prescription, multivariable logistic regression analysis was applied and the results were presented as odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). On multivariate logistic regression models, higher NYHA classes (OR 0.49, 95%CI 0.26–0.94), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (OR 0.17, 95% CI 0.04–0.85), chronic kidney disease (OR 0.40, 95% CI 0.19–0.83), and heart rate under 65 (OR 0.34, 95% CI 0.12–0.98) were associated with a reduced likelihood of prescription. In this study, we found a low rate of beta-blocker prescriptions, with only around half of the participants being prescribed beta-blockers. Further studies are needed to examine the reasons for the under-prescription of beta-blockers, and to evaluate the long-term benefits of beta-blockers in elderly patients with HFrEF in this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Heart failure in older people is a growing and evolving public health challenge, contributing to added pressures on healthcare systems worldwide1,2. Heart failure is a clinical syndrome characterized by symptoms and signs resulting from any structural or functional impairment of ventricular filling or ejection of blood2,3. The prevalence and incidence of heart failure increase significantly with age and can reach approximately 20% in people 75 years and older4.

Apart from age being an irreversible significant risk factor, other geriatric factors such as multimorbidity, polypharmacy, cognitive impairment and frailty can make the management of heart failure in older people complex1,5. With the growing population of older people and how the prevalence of heart failure doubles with each decade, managing heart failure in older people continues to be one of the major challenges in cardiovascular care2,6.

The major goals of therapy in heart failure management include improving quality of life, reducing mortality risk and preventing hospital readmission2,7. Studies have shown that in patients with heart failure, particularly heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), treatment with beta-blockers can reduce mortality and hospitalization risk, and improve their clinical status, symptoms of heart failure and left ventricular ejection function2,8,9,10,11,12,13. The benefits of beta blockers were consistent in older patients3,14,15. In patients with HFrEF, long-term treatment of beta-blockers is recommended to reduce the risk of major cardiovascular events2,3. However, beta blockers are sometimes underused in practice for various reasons, particularly in older patients with HFrEF16.

In Vietnam, heart failure was responsible for approximately 15% of all hospitalizations17,18. Older patients with heart failure in Vietnam had a high burden of symptoms which may require more resources for care, adding further strain to the health system19. However, there is limited evidence of the pharmacological treatment of heart failure in older adults, particularly the use of beta blockers in this population. Against this context, there is a need for more studies to better understand how care is provided for older patients with heart failure in Vietnam.

This study aims to examine the prevalence of beta-blocker prescription and its associated factors in older hospitalized patients with HFrEF in Vietnam.

Methods

Study design and population

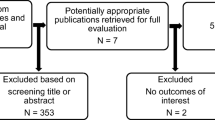

This is a prospective observational study conducted at the Department of Interventional Cardiology and Department of Cardiology, Thong Nhat Hospital in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam from July 2019 to July 2020. Patient selection was carried out by reviewing the medical records. Patients were invited to participate in the study if they met the following criteria: (1) aged ≥ 60 years, (2) having a diagnosis of chronic HFrEF in the medical records, (3) hospitalized for at least 48 h. Patients were excluded from this study if (1) they had de novo heart failure; (2) they had contra-indications of using beta-blockers (such as cardiogenic shock, 2nd or 3rd degree AV block, sick sinus syndrome, liver failure, severe chronic pulmonary obstructive disease); (3) they did not provide consent; (4) they died during hospitalization.

All consecutive patients admitted to the hospital with heart failure were invited to participate in the study. If a patient admitted to the hospital more than once during the study period, the first admission that had a length of hospitalization > 48 h was chosen.

Ethics approval and informed consent

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Thong Nhat Hospital in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam (107/2020/BVTN-HDYD). Informed consent was obtained from all participants. This study was compiled in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data collection

Data were collected from medical records. Information obtained included: demographic characteristics, height, weight, heart rate and blood pressure measures, comorbidities, medications prescribed during admission, and laboratory results during admission.

Outcome definition

The outcome of this study was the prescription of evidence-based beta-blockers for the treatment of HFrEF (including bisoprolol, carvedilol, metoprolol, nebivolol). Beta-blocker prescription was defined based on the medical records during admission.

Predictive variables

The potential variables that can be associated with the prescription of beta-blockers included age, sex, body mass index, New York Heart Association (NYHA) classes, heart rate, comorbidities including hypertension, ischemic heart disease, atrial fibrillation, valvular heart disease, dilated cardiomyopathy, diabetes, dyslipidemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and chronic kidney disease.

Statistical analysis

Analysis of the data was performed using SPSS for Windows 29.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous variables are presented as means ± standard deviation, and categorical variables as frequencies and percentages. Comparisons between groups (with and without beta-blocker prescriptions) were conducted using the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney test for continuous variables.

To explore the factors associated with beta-blocker prescription, multivariable logistic regression analysis was applied. First, univariable logistic regression was performed on all the potential associated factors in the dataset, based on clinical rationale (such as age, sex, comorbidities, NYHA classes, and comorbidities). Variables that had a p-value < 0.05 on univariable analysis were selected for multivariable analysis.

Results were presented as odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Results

Participants characteristics

A total of 190 participants were recruited. Their mean age was 75.50 (± 9.05) years and 46.8% of the participants were female. NYHA III was the most common heart failure severity stage, occurring in 66.8% of patients. The average number of comorbidities were 3 (± 1.16), with the most common comorbidity being hypertension (83.7%), followed by ischemic heart disease (80.5%), diabetes mellitus (35.3%), dyslipidemia (34.7%), and atrial fibrillation (31.6%) (Table 1).

Among the 190 participants, 55.3% (105/190) were prescribed beta-blockers (83.8% received bisoprolol and 16.2% received nebivolol). Participants who did not receive beta-blocker prescription were significantly older (mean age 77.45 ± 8.93 versus 73.92 ± 8.87, p = 0.007), had higher prevalence of chronic kidney disease (36.5% versus 15.2%, p < 0.001), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (12.9% versus 1.9%, p = 0.003), and had higher levels of NTproBNP (7248.76 ± 9730.11 versus 3669.45 ± 5113.77 pg/mL, p = 0.003) and serum creatinine (144.37 ± 59.13 versus 118.15 ± 60.84 mcmol/l, p = 0.003) compared to participants who were prescribed beta-blockers (Table 1). The prescription rates of beta-blockers by comorbidity types are presented in Fig. 1.

Prescriptions of other medications for heart failure

Overall, 80.5% of participants were prescribed a renin-angiotensin system inhibitor (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors—ACEIs, or angiotensin receptor blockers—ARBs), 68.9% received mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs), 76.8% received loop diuretics, 6.3% received ivabradine, 26.3% received digoxin and 50.5% received nitrate.

Participants with beta-blocker prescription had significantly higher prescription rates of ACEIs/ARBs (89.5% versus 69.4%, p < 0.001), MRAs (75.2% versus 61.2%, p = 0.037), but lower rates of prescriptions of loop diuretics (67.6% versus 88.2%, p < 0.001) and nitrate (41.9% versus 61.2%, p = 0.008) compared to participants without beta-blocker prescription (Table 2).

Factors associated with beta-blocker prescriptions

Table 3 describes the unadjusted odds ratios of the potential factors that can be associated with beta-blocker prescription. On multivariate logistic regression models, higher NYHA classes (OR 0.49, 95%CI 0.26–0.94), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (adjusted OR 0.17, 95% CI 0.04–0.85), chronic kidney disease (adjusted OR 0.40, 95% CI 0.19–0.83), and heart rate < 65 bpm (adjusted OR 0.34, 95% CI 0.12–0.98) were significantly associated with a reduced likelihood of beta-blocker prescription (Fig. 2).

Discussion

In this study of 190 older hospitalized patients with HFrEF, there was low uptake of beta-blocker prescriptions, with only 55.2% of the participants prescribed beta-blockers. Participants with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, higher NYHA classes and heart rate < 65 bpm had lower odds of being prescribed beta-blockers.

Under-utilization of beta-blockers in patients with HErEF has been reported in many studies in other countries. In a study of 1825 patients (mean age 77.3 ± 13.2) admitted for heart failure for the first time between 2009 and 2011 in France, the prescription rates of beta-blockers before admission ranged from 26 to 32%, and 46–54% at discharge20. In a study of 1075 patients with heart failure (age range 62–84) in Central Asia and Europe in the period 2013–2019, the rates of beta-blocker use at admission in patients with HFrEF ranged from 43.5% in Central Asia to 59.1% in Europe21. In a study of 1509 patients (mean age 63.9 ± 16.1) hospitalized for acute HFrEF in 21 hospitals in Taiwan in 2014, 60% were prescribed beta-blockers at discharge22. Some other studies reported higher prescription rates of beta-blockers for patients with HFrEF. For example, a multi-centered study in 1853 older patients (age range 61–77) in Germany conducted from 2009 to 2011 reported that 71.0% of the participants were treated with beta-blockers at admission and 89% at discharge23. In a study of 1003 patients (mean age 54.4 ± 15.0) recruited from 2016 to 2019 in China, the prescription rate of beta-blockers in hospitalized patients with HFrEF was 84.2%24. The younger age of the participants and the fact that patients with heart rates < 75 bpm were excluded from that study may explain a higher prescription rate compared to our study24.

The novelty of our study lies in its unique contribution to the evidence of the prescription of beta-blockers among older patients with HFrEF within the context of Vietnam. Our study was the first to be specifically designed to examine the use of beta-blockers in older patients with HFrEF in Vietnam. There is a scarcity of research in older patients with heart failure in Vietnam and most of them focused on the quality of life and symptom burden19,25,26. In a pilot study in 257 patients with heart failure (mean age 64 ± 15 years) examining the implementation of the Optimize Heart Failure Care Program for patients with heart failure in Vietnam, the investigators noticed a low rate of prescription of beta-blockers at time of hospital discharge (approximately 33%), which is consistent with our finding26. Given the rising prevalence of cardiovascular diseases, particularly heart failure in this country, the limited number of studies highlights a crucial gap in understanding and addressing this health concern. Our research stands among the few studies addressing this critical health issue in older adults in Vietnam. This focus on an understudied population and therapeutic approach highlights the innovative nature of our work and its potential to inform and improve clinical practices in the country. Our research provides valuable insights into the local epidemiology and management practices. The low prescription of beta-blockers raises concerns about inadequate management and the need for increased promotion and education on beta-blocker use in elderly patients with HFrEF in Vietnam. In this study, although all beta-blockers prescribed were β1-selective agents (bisoprolol and nebivolol), the presence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was significantly associated with reduced odds of receiving beta-blockers (by 83%). This may reflect the extra-caution of the physicians in prescribing beta-blockers for older patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, although research has affirmed that selective β1-blockers are safe in patients with concomitant HFrEF and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease16. Of note, our study found that chronic kidney disease was presented in one-quarter of the studied participants and reduced the odds of receiving beta-blockers by 60%.

More studies are needed in older patients with HFrEF in Vietnam to understand the factors associated with the non-prescription of beta-blockers. The reasons for the low prescription of beta blockers among older patients with HFrEF are usually multi-faceted. Due to the higher comorbidities and increased risk of adverse side effects in older patients, physicians may be reluctant to prescribe beta-blockers. Polypharmacy and concomitant use of other medications are other aspects that can limit the prescription of beta-blockers. These results emphasize the need for continued vigilance towards the utilization of evidence-based treatment strategies, including evidence-based beta-blockers in older patients with HFrEF. The results of this study imply that healthcare providers need to assess their current prescribing practices of beta-blockers in older patients with HFrEF. By addressing the identified barriers to prescribing beta-blockers, healthcare providers can improve the management of HFrEF in older patients.

There are a few limitations to this study. Firstly, it was carried out on older patients from one hospital, so it may not accurately reflect all older patients with HFrEF in Vietnam. The inclusion criterion of having a diagnosis of chronic HFrEF was based on the medical records and we were unable to capture details such as the duration of having a diagnosis of HFrEF and the participants’ previous EF measurements, so there is a chance that several participants with HFpEF may be mis-classified as HFrEF. In addition, we did not collect information related to socioeconomic status, diet, or other local-specific factors and patient-specific factors (such as a history of intolerance and side effects of beta-blockers) that may have an influence on the prescription of beta-blockers. Therefore, the study findings should be cautiously interpreted.

In conclusion, in this study only around half of the participants with HFrEF were prescribed beta-blockers. These results suggest that the use of beta-blockers in older patients with HFrEF needs more attention to improve patient outcomes. Further studies are needed in older patients with HFrEF in Vietnam to examine the reasons for the under-prescription of beta-blockers, and to evaluate the long-term benefits of beta-blocker use in elderly patients with HFrEF.

Data availability

The dataset used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Butrous, H. & Hummel, S. L. Heart failure in older adults. Can. J. Cardiol. 32(9), 1140–1147 (2016).

McDonagh, T. A. et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: Developed by the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) With the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur. Heart J. 42(36), 3599–3726 (2021).

Heidenreich, P. A. et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 145(18), e895–e1032 (2022).

Díez-Villanueva, P. & Alfonso, F. Heart failure in the elderly. J. Geriatr. Cardiol. 13(2), 115–117 (2016).

Li, H. et al. Targeting age-related pathways in heart failure. Circ. Res. 126(4), 533–551 (2020).

Mosterd, A. & Hoes, A. W. Clinical epidemiology of heart failure. Heart 93(9), 1137 (2007).

Ponikowski, P. et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur. Heart J. 37(27), 2129–2200 (2016).

CIBIS-II Investigators. The cardiac insufficiency bisoprolol study II (CIBIS-II): A randomised trial. The Lancet 353(9146), 9–13 (1999).

Packer, M. et al. Effect of carvedilol on the morbidity of patients with severe chronic heart failure: Results of the carvedilol prospective randomized cumulative survival (COPERNICUS) study. Circulation 106(17), 2194–2199 (2002).

Metoprolol, C. R. Effect of metoprolol CR/XL in chronic heart failure: Metoprolol CR/XL Randomised Intervention Trial in-Congestive Heart Failure (MERIT-HF). The Lancet 353(9169), 2001–2007 (1999).

Bristow, M. R. et al. Carvedilol produces dose-related improvements in left ventricular function and survival in subjects with chronic heart failure, MOCHA Investigators. Circulation 94(11), 2807–2816 (1996).

Hjalmarson, A. et al. Effects of controlled-release metoprolol on total mortality, hospitalizations, and well-being in patients with heart failure: The Metoprolol CR/XL Randomized Intervention Trial in congestive heart failure (MERIT-HF), MERIT-HF Study Group. Jama 283(10), 1295–1302 (2000).

Cleland, J. G. F. et al. Beta-blockers for heart failure with reduced, mid-range, and preserved ejection fraction: An individual patient-level analysis of double-blind randomized trials. Eur. Heart J. 39(1), 26–35 (2018).

Gilstrap, L. et al. Association between beta-blockers and mortality and readmission in older patients with heart failure: An instrumental variable analysis. J. Gener. Internal Med. 36(8), 2361–2369 (2021).

Flather, M. D. et al. Randomized trial to determine the effect of nebivolol on mortality and cardiovascular hospital admission in elderly patients with heart failure (SENIORS). Eur. Heart J. 26(3), 215–225 (2005).

Masarone, D., Martucci, M. L., Errigo, V. & Pacileo, G. The use of β-blockers in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 8, 9 (2021).

Reyes, E. B. et al. Heart failure across Asia: Same healthcare burden but differences in organization of care. Int. J. Cardiol. 223, 163–167 (2016).

Savarese, G. et al. Global burden of heart failure: A comprehensive and updated review of epidemiology. Cardiovasc. Res. 118(17), 3272–3287 (2022).

Nguyen, T. T. et al. Symptom burden among hospitalised older patients with heart failure in Hanoi, Vietnam. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 20 (2022).

Eschalier, R. et al. Impact of clinical characteristics and management on the prognosis of unselected heart failure patients. Cardiovasc. Drugs Therapy 29(1), 89–98 (2015).

Abdurashidova, T. et al. European Society of Cardiology guidelines and 1 year outcomes of acute heart failure treatment in Central Asia and Europe. ESC Heart Fail. 11(1), 483–491 (2024).

Chang, H.-Y. et al. Gap between guidelines and clinical practice in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: Results from TSOC-HFrEF registry. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 80, 12 (2017).

von Scheidt, W. et al. Characteristics, management modalities and outcome in chronic systolic heart failure patients treated in tertiary care centers: Results from the EVIdence based TreAtment in Heart Failure (EVITA-HF) registry. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 103(12), 1006–1014 (2014).

Zhou, J. et al. Effectiveness and safety of ivabradine in Chinese patients with chronic heart failure: An observational study. ESC Heart Fail. 11(2), 846–858 (2024).

Truong, H. P., Nguyen, K. M., Tran, H. T. & Hoang, S. V. Assessment of health-related quality of life in patients with chronic heart failure: A cross-sectional study in Vietnam. Cureus 15(12), e51098 (2023).

Do, T. N. P. et al. Effect of the optimize heart failure care program on clinical and patient outcomes—the pilot implementation in Vietnam. Int. J. Cardiol. Heart Vasc. 22, 169–173 (2019).

Funding

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TVN designed the study. TVN and HTKN led the recruitment and data acquisition. All authors (TVN, HTKN, WJW, FA, TNN) were involved in analysis, interpretation of data, and drafting the manuscript. All authors revised it critically for important intellectual content.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Van Nguyen, T., Nguyen, H.T.K., Wong, W.J. et al. The prescription of beta-blockers in older patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: an observational study in Vietnam. Sci Rep 14, 12923 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-63479-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-63479-w

- Springer Nature Limited