Abstract

Low serum 25(OH)D levels (< 30 nmol/L) have been associated with increased depressive symptom scores over time, and it is believed that functionality may play a mediating role in the relationship between 25(OH)D and depressive symptoms. To comprehend the association between these factors could have significant implications for public health policy. The aim of this study was to verify the association between simultaneous vitamin D insufficiency and depressive symptoms, and functional disability in community-dwelling older adults. This was a cross-sectional study with data from the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Aging (ELSI-Brazil), collected between 2015 and 2016. The outcomes were functional disability assessed through basic activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL). The exposures were vitamin D insufficiency (< 30 nmol/L) and depressive symptoms (≥ 4 points in 8-item version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression). Crude and adjusted Poisson regression was performed to estimate associations. A total of 1781 community-dwelling older adults included in this study, 14.6% had disability in ADL and 47.9% in IADL; 59.7% had vitamin D insufficient levels, and 33.2% depressive symptoms. The concomitant presence of vitamin D insufficient and depressive symptoms increased the prevalence of ADL by 2.20 (95% CI: 1.25; 3.86) and IADL by 1.54 (95% CI: 1.24; 1.91), respectively. Therefore, preventive strategies to keep older adults physically and socially active, with a good level of vitamin D, are essential to avoid depression and functional disability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Aging is a normal development process, and it occurs in an irreversible, progressive, and natural manner1. An important marker of healthy aging is functional capacity, which refers to a person’s ability to perform essential daily activities for self-care and independent living. Assessing an older adult’s function involves evaluating their ability to perform basic activities of daily living (ADL) and more complex activities, known as instrumental activities of daily living (IADL). When they cannot perform these tasks independently, it indicates a loss of function, requiring daily assistance. This often increases their care needs, impacting their quality of life and increasing the demand for healthcare services1,2,3.

Functional disability can be associated with genetic inheritance and individual and behavioural characteristics, and it is related to autonomy in later life4,5,6,7. In addition to these risk factors, depressive symptoms8,9,10 and vitamin D insufficiency11,12,13,14,15,16 are also associated with functional disability. Depression is the second most common cause of functional loss and psychosocial disability in the general population. This is characterized by the presence of depressive symptoms. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), at least 10.0% of older adults suffer from this condition, which is one of the disorders that most compromise the quality of life of this population17,18,19.

Depressive symptoms and impairment in functionality reinforce each other, progressing to disability. Additionally, other illnesses may emerge as disability and depression set in20. Some physical illnesses resulting from depressive symptoms are explained by the decline in the immune system, as the neurological, endocrine, and immune systems are related to the regulatory functions of the organism in response to internal and external stimulation21,22,23.

It is also known that vitamin D insufficiency is prevalent in the older adults, affecting more than 50% of globally population24 and this may imply psychiatric and neurological disorders25, as individuals show greater cognitive impairment, depressive symptoms, and anxiety26. There is a belief that vitamin D receptors, promoted in brain regions where serotonin genes are present, play a role in these manifestations27,28. In addition, the decrease in serum levels of vitamin D in individuals with depressive symptoms can be seen in a secondary way, because due to the symptoms, they spend more time at home, exposing themselves less to the sun and with a poor diet27. Vitamin D insufficiency is associated with decreased physical performance, reduced mobility, deterioration of muscle function, and increased incidence of falls and fractures in the older population11,12,13, 26.

Functional capacity is associated with vitamin D insufficiency, as well as the presence of depressive symptoms, but the interrelationship between depressive symptoms and vitamin D and how it affects functional capacity is poorly explored. It is known that low serum 25(OH)D levels (< 30 nmol/L) are associated with increased depressive symptom scores, and it is suggested that functionality may have a mediating role in the relationship between 25(OH)D and symptoms depressive. However, vitamin D supplementation does not show an association with the reduction of depressive symptoms and improvement in physical functioning29.

The investigation and comprehension of the association between vitamin D insufficiency, depressive symptoms, and functional disability among community-dwelling older adults could have significant implications for public health policies. Although there is still a gap in the literature regarding their association, these are preventable conditions. The aim of the present study was to verify the association between simultaneous vitamin D insufficiency and depressive symptoms, and functional disability in community-dwelling older adults. Our hypothesis was that the combination of vitamin D insufficiency and depressive symptoms increases the prevalence of functional disabilities in the older adults.

Methods

Study design

This was a cross-sectional study with data from the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Aging (ELSI-Brazil). A population-based longitudinal study, representative of the non-institutionalized Brazilian population aged 50 and over. The baseline survey was carried out between 2015 and 2016, in 70 municipalities in the 5 Brazilian geographic regions. To ensure that the sample represents the urban and rural areas of municipalities of all sizes, the sample was recruited using a design with selection stages, combining stratification of the primary sampling units (municipalities), census sectors, and households. Detailed information on design, recruitment methods, and topics covered are available in the study by Lima-Costa et al.30.

The ELSI-Brazil project was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (FIOCRUZ), Minas Gerais (CAAE: 34649814.3.0000.5091). All participants or legal guardian signed separate informed consent forms before they participated in the study. This study was carried out according to the Resolution n° 466/2012, of the National Council of Health, from the Brazilian Ministry of Health, and principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (1964).

Population and sample

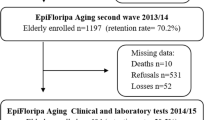

For the present study, ELSI-Brazil participants with complete information aged 50 and over, who underwent blood collection and with complete data, were included. Individuals aged 50 years were included because changes inherent to aging start from the fifth decade of life, especially in developing countries. The total number of Elsi-Brazil participants is 9412. Participants aged 80 years and over were excluded due to the low sample size (n = 104). The other reasons for exclusion were presented in Fig. 1 (n = 7527). The analysis sample of the present study was 1781 participants.

Outcome variable

Functional disability was independently investigated through two variables: difficulty in performing ADL (bathing, dressing, eating, being continent, having sexual activities, and sleeping independently) and in performing IADL (taking the bus, shopping, managing finances, managing medication use, and using the phone)31. The responses to the variables were classified as either having no difficulty or difficulty in one or more activities for those who reported difficulty or need help in at least one activity32,33.

Exposure variables

The exposure variables were the vitamin D insufficiency and the presence of depressive symptoms. Four groups based on a combination of vitamin D insufficiency depressive symptoms were created: (1) sufficient vitamin D and no depressive symptoms; (2) sufficient vitamin D and depressive symptoms; (3) vitamin D insufficiency and no depressive symptoms, and; (4) vitamin D insufficiency and depressive symptoms.

Vitamin D was collected by a trained laboratory technician at the participant’s home while fasting. All biological samples were sent to the central laboratory at Oswaldo Cruz Foundation30 located in São Paulo and, depending on the distance, they were sent by air. The samples were stored on dry ice and during transport, the temperature was constantly monitored. A chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay with an automatic analyser was used to measure the serum level of 25(OH)D, whose analytical sensitivity is 8.5 nmol/L, and the coefficient of variation ranged from 5.8 to 6.2%30,31. Regarding vitamin D levels, it was considered insufficient (< 30 nmol/L) and sufficient (≥ 30 nmol/L)34,35.

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the short version of the CES-D-8 scale36. The eight questions referred to the week before the interview and participants answered “yes” or “no” to the presence of a certain symptom. The score ranged between 0 and 8 and, in the present study, ≥ 4 symptoms were classified as the presence of depressive symptoms and ≤ 3 symptoms as the absence of depressive symptoms37.

Adjustment variables

The following adjustment variables were used for this analysis: age (in years), sex (female and male), skin color (white, brown, black, yellow, indigenous), education in years (no formal education, 1 to 4 years, 5 to 8 years, 9 to 11 years, ≥ 12 years), marital status (with or without a partner), per capita income (in tertiles), nutritional status by body mass index (BMI) [low weight (< 18.5 kg/m2), normal (≥ 18.5 to 25 kg/m2), overweight (≥ 25 to 30 kg/m2), obesity (≥ 30 kg/m2)], physical activity level [active (≥ 150 min) and insufficiently active (< 150 min)]38,39,40, cognitive function31 (z score of ≤ − 1SD considered with cognitive impairment41), geographic region of residence (North, Northeast, Midwest, Southeast, and South) and season of the year during vitamin D collection (summer, autumn, winter, and spring).

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using the Stata SE 16 software, considering the sample weights due to the sample selection. The descriptive analysis was presented in relative frequency with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). For continuous data, measures of central tendency and dispersion were used. A bivariate analysis was performed between the dependent variables, difficulty in ADL and IADL, and the independent variables, and the test χ2 was adopted to test associations, in categorical variables, and Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables.

Crude and adjusted Poisson regression, with respective 95% CI, were used to investigate measures of association between outcome and exposures. After the adjusted analysis, the interaction of the combination of vitamin D insufficiency and depressive symptoms with age was tested using the post-estimation with the margins command, which is presented graphically.

Ethical approval

The ELSI-Brazil was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (FIOCRUZ), Minas Gerais, with Certificate of Presentation for Ethical Consideration (CAAE) number 34.649.814.0000.5091. All participants interviewed in the study consented by signing a free and informed consent form to participate in the study.

Results

Of the 9412 ELSI participants at baseline, only 2263 had vitamin D samples collected. 482 participants were excluded due to missing data (1 in ADL, 7 in IADL, 280 in CES-D-8, and 194 in covariates), totalling 1,781 participants included in the present analysis (Fig. 1). The mean age of the participants was 63.4 years (SD = 9.2). Most were women (52.1%), had a partner (56.9%), with 1 to 4 years of education (37.4%), were from the white race/ethnicity group (44.8%), upper income tertile (37.8%), physically active (68.7%) and, overweight (36.0%).13.0% had below 1SD of the memory score, most participants were from the Southwest and vitamin D was collected in spring. Overall, 59.7% had insufficient vitamin D levels, 33.2% had increased depressive symptoms, 14.6% had difficulties with ADL, and 47.9% in IADL (Table 1).

In the bivariate analysis, there was a significantly higher prevalence of those who had difficulties in performing ADL among women, those with no formal education, those who were physically inactive, those with low BMI, with the presence of depressive symptoms, and those with insufficient vitamin D. Regarding IADL difficulties, the prevalence was significantly higher in women, in those with low education, and in those without depressive symptoms and with vitamin D insufficiency (Table 1).

In the crude analysis, the presence of depressive symptoms alone and combined with vitamin D insufficiency were associated with ADL disability. This association remained significant in the fully adjusted model. The combination of depressive symptoms with vitamin D insufficiency increases by 2.20 (95% CI: 1.25; 3.86) the prevalence of ADL disability to those who had sufficient levels of vitamin D and no depressive symptoms (Table 2).

Regarding IADL disability, the presence of depressive symptoms was associated with the presence of difficulties in carrying out activities in the crude and fully adjusted analysis, with a 49.0% increase in prevalence (PR: 1.49; 95% CI: 1.29; 1.72). Vitamin D insufficiency was not associated with IADL. When depressive symptoms were combined with vitamin D insufficiency, both in the crude and adjusted analyses, being insufficient in vitamin D levels alone was associated with a 62% increase in disability in the adjusted analysis (PR: 1.62; 95% CI: 1.35; 1.95). The combination of depressive symptoms and vitamin D insufficiency increased the prevalence by 54% (PR: 1.54; 95% CI: 1.24; 1.91), while sufficient levels of vitamin D and depressive symptoms were not associated with IADL disability (Table 2).

Figure 2 shows the interaction of the vitamin D insufficiency and depressive symptoms with age about ADL. There is an increase in the prevalence of functional disability with increasing age, but it occurs differently for those who have only depressive symptoms and sufficient levels of vitamin D.

Figure 3 shows the evolution of IADL with aging. Overall, there is an increase in functional disability concerning age for all vitamin D and depressive symptoms groups. However, for those who have both conditions and insufficient vitamin D alone, the IADL increase is greater than in the other groups.

Discussion

The key findings of the present study showed that vitamin D insufficiency and, mainly, the concomitant presence of depressive symptoms increase the prevalence of functional disability, thus compromising the performance of both ADL and IADL. The prevalence of functional disabilities has increased with age. However, this increase did not occur to the same extent for ADL and IADL concerning the combination of vitamin D status and the presence of depressive symptoms.

The study by Koning et al.29, with old Dutch adults, showed that 17.0% of the participants had vitamin D deficiency. Depressive symptoms affected 15.1% of the sample at the beginning of the study and after six years it increased to 19.8%. In a cross-sectional analysis, there was no significant association between vitamin D and depressive symptoms. However, in a longitudinal analysis, older women with vitamin D concentrations less than 75 nmol/L had 17.0% to 24.0% more depressive symptoms than women with vitamin D concentrations greater than 75 nmol/L. The Brazilian older adults in the present study showed higher levels of vitamin D insufficiency and the presence of elevated depressive symptoms. However, the association with reduced functionality was similar.

Rafiq et al.42 showed that participants with lower levels of vitamin D were older, with worse physical performance and more depressive symptoms. Chronic diseases, depressive symptoms, and physical performance proved to be mediators in explaining the relationship between vitamin D and quality of life. The characterization of the study sample and the categorization values were also different from our study, as they considered levels < 25 nmol/L as deficiency, from 25 to 50 nmol/L as insufficiency, and > 50 nmol/L as sufficient, not allowing a proper comparison. However, functional worsening was present in those with advanced age, with vitamin D insufficiency and depressive symptoms, as in the present study.

The presence of low vitamin D levels has been reported26 as a cause for the functional decrease due to the appearance of muscle weakness, osteomalacia, hyperparathyroidism, and, consequently, increased bone reduction, favouring the onset of osteoporosis and osteopenia. These factors cause less mobility and a higher incidence of falls and fractures. On the other hand, functional disability makes it impossible for vitamin D to perform its functions actively and effectively43. In the present study, our sample showed no impairment in ADL, as they were active and functional, but when depressed, having the association of vitamin D insufficiency with depressive symptoms further increased functional impairment.

Depressive symptoms can increase the chance of ADL and IADL impairment44, as depressive symptoms can lead to an inactive lifestyle45,46 and to reinforce the damage caused by vitamin D insufficiency, through reduced by sun exposure and lower nutritional consumption combined with the decrease in nutrient metabolism, commonly reduced during aging47.

The opposite relationship is also addressed by authors, in which vitamin D deficiency is considered a cause of presence of depressive symptoms26,27. The presence of vitamin D receptors in places in the brain where serotonin is produced explains the onset of cognitive impairment, depressive symptoms, and anxiety after vitamin D insufficiency27,48.

More than half of the participants in our study did not report elevated depressive symptoms. A possible explanation for this low percentage is that our sample had a younger population and, therefore, the tendency to present the factors that influence the onset of depressive symptoms was smaller. Because they do not present the functional impairments that affect the oldest old, our sample also presented the characteristic of being active and functional. Being physically active is a protective factor for depression and, similarly, the more functional, with a higher level of physical activity, the lower the risk of depressive symptoms49.

It is usual to find Brazilians and internationals studies with older adult and the results point to vitamin D insufficiency. Even in the sunniest regions, low serum levels of this vitamin are common, as just the presence of sunlight alone is not enough. In addition, the skin of the older adults loses effectiveness, further reducing the ability to synthesize vitamin D through sun exposure. Another factor that can decrease the serum levels of vitamin D in later life is being overweight, as the increase in body fat makes it difficult to distribute vitamin D due to the decrease in bioavailability47.

We investigated the magnitude of the increase in disability at all ages and its relationship with depressive symptoms and vitamin D insufficiency. The greater disability observed could be explained, since presence of depressive symptoms often increases with age50, as physiological changes affect physical functioning, compromising basic skills such as sitting, walking, getting up; and, consequently, the quality of life, due to low self-esteem and increased depressive symptoms51. As for vitamin D, the aging process can cause a decline in renal function, consequently decreasing the renal production of 1,25(OH)2D47. Also, with advancing age, the concentration of the intestinal vitamin D receptor decreases, signalling that it is one of the causes of resistance to 1,25(OH)2D in the, consequently leading to a decrease52.

Previous studies carried out in various states of Brazil found characteristics that are like our study as a profile of the older adults: being female53,54, having a partner53,55, and having low education56. Data from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) also confirm that women and the white race are the majority among the elderly57. What justifies this finding is the characteristic that follows the aging process of having a greater number of long-lived women than men. In this regard, the United Nations (UN) estimate is that by 2040 there will be 6.2 million more women than men58.

In our research, we included the age group between 50 and 59 years to follow the beginning of the aging process. However, in some studies54,55,56, the participants included are those over 60 years of age, and the age group between 60 and 69 years prevailed. Although this study presents very important points, its limitations should be highlighted. Firstly, the type of study does not allow establishing a temporal relationship. Secondly, there is the bias of non-participants that causes sample loss in the study because the weakest tend not to participate. Third, the instruments used are widely used in other studies and allow comparisons with research at a global level, but they are self-reported measures and can be influenced by social, environmental and psycho-emotional factors, in addition to being subject to memory or information bias. Although vitamin D insufficiency alone has caused little impairment in functionality, it is necessary to maintain sufficient serum levels of vitamin D, because, regardless of the initial factor, whether depressive symptoms or even other possible physical condition impairments that arise from the aging process, the loss of function will become even greater if an older adult is impaired. Therefore, strategies to keep this population active and with good levels of vitamin D are important. Including those at risk of hypovitaminosis D and contraindications to sun exposure, vitamin D supplementation needs to be considered.

Daily activities, such as walking to the market, and keeping the house clean and organized, among others, are very important for maintaining the elderly’s independence. However, access to physical activity is essential for the aging process to take place with quality. Cooperating with the maintenance of serum levels of vitamin D, physical activities can be performed outdoors and in groups, encouraging social interaction. Integrative, multitasking, playful, and recreational practices can also be added to contribute not only to the prevention/recovery of depression but also to cognitive maintenance.

The maintenance and recovery of functional capacity resulting from the interaction of multiple factors, physical and mental health, conditions to independently perform common daily tasks, participation in community life, economic independence, being able to count on family support, and having access to health care professionals. Likewise, depressive symptoms are not just a physiological response that emerges during the aging process, but a multifactorial consequence that needs to be carefully observed.

We recommend that new studies investigate the longitudinal relationship between depressive symptoms and vitamin D on functionality, considering the region of residence and the season of data collection. Consider an analysis that considers categories such as deficiency, insufficiency and sufficiency of vitamin D. It is worth noting that Brazil is a country of large dimensions, climate and means of subsistence. In this sense, the availability of food itself differs in each region, which is directly related to vitamin D. In the present study, we did not include data on nutrition, but we reinforce the suggestion for future studies.

Final considerations

The concomitant presence of vitamin D insufficiency and depressive symptoms increases the chances of functional disability in adults. Healthcare professionals can prioritize the early identification and treatment of vitamin D deficiencies and depressive symptoms in adult patients to help reduce the risk of functional disability.

Data availability

The data can be accessed at https://elsi.cpqrr.fiocruz.br/data-access/

References

Officer, A. & Manandhar, M. UN Decade of Healthy Agein 2020–2030. World Health Organization (2020).

Khodadad Kashi, S., Mirzazadeh, Z. S. & Saatchian, V. A systematic review and meta-analysis of resistance training on quality of life, depression, muscle strength, and functional exercise capacity in older adults aged 60 years or more. Biol. Res. Nurs. 25, 88 (2023).

Gao, Q. et al. Associated factors of sarcopenia in community-dwelling older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13124291 (2021).

Tang, K. F., Teh, P. L. & Lee, S. W. H. Cognitive frailty and functional disability among community-dwelling older adults: A systematic review. Innov. Aging https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igad005 (2023).

Briggs, R. et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment for community-dwelling, high-risk, frail, older people. Cochr. Database Syst. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012705.pub2 (2022).

Cristina Viana Campos, A. et al. Prevalência de incapacidade funcional por gênero em idosos brasileiros: Uma revisão sistemática com metanálise. Rev. Bras. Geriatria Gerontol. 19, 545 (2016).

Meneguci, C. A. G., Meneguci, J., Tribess, S., Sasaki, J. E. & Júnior, J. S. V. Incapacidade funcional em idosos brasileiros: Uma revisão sistemática e metanálise. Revista Brasileira de Ciências do Envelhecimento Humano https://doi.org/10.5335/rbceh.v16i3.9856 (2019).

Zhao, Y. W. et al. The effect of multimorbidity on functional limitations and depression amongst middle-aged and older population in China: A nationwide longitudinal study. Age Ageing 50, 190 (2021).

Lenze, E. J., Barco, P. P. & Bland, M. D. Depression and functional impairment: A pernicious pairing in older adults. Amer. J. Geriatric Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2017.09.028 (2018).

Zenebe, Y., Akele, B., Selassie, M. & Necho, M. Prevalence and determinants of depression among old age: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. General Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.1186/s12991-021-00375-x (2021).

Remelli, F., Vitali, A., Zurlo, A. & Volpato, S. Vitamin D deficiency and sarcopenia in older persons. Nutrients https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11122861 (2019).

El Díez, J. J. sistema endocrino de la vitamina D: Fisiología e implicaciones clínicas. Revista Española de Cardiología Suplementos 22, 1–7 (2022).

Quesada Gómez, J. & Sosa Henríquez, M. Vitamina D y función muscular. Revista de Osteoporosis y Metabolismo Mineral 11, 3–5 (2019).

Cashman, K. D. et al. Vitamin D deficiency in Europe: Pandemic?. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 103, 1033 (2016).

Zhang, C. et al. Associations between complement components and vitamin D and the physical activities of daily living among a Longevous population in Hainan, China. Front. Immunol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.01543 (2020).

Alekna, V., Kilaite, J., Mastaviciute, A. & Tamulaitiene, M. Vitamin D level and activities of daily living in octogenarians: Cross-sectional study. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 9, 383353 (2018).

Oliveira, A. S. & Rossi, E. C. Envelhecimento populacional, segmento mais idoso e as atividades básicas da vida diária como indicador de velhice autônoma e ativa. Geosul 34, 358 (2019).

Jesus, De. et al. Sintomas de depressão, risco nutricional e capacidade funcional em idosos longevos. Estudos Interdisciplinares em Psicologia 12, 3 (2021).

World Health Organization. OMS | Depressive disorder. WHO (2016).

Mlinac, M. E. & Feng, M. C. Assessment of activities of daily living, self-care, and independence. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 31, 506 (2016).

Stubbs, B. et al. Depression and physical health multimorbidity: Primary data and country-wide meta-analysis of population data from 190 593 people across 43 low- and middle-income countries. Psychol. Med. 47, 2107 (2017).

Bourassa, K. J., Memel, M., Woolverton, C. & Sbarra, D. A. Social participation predicts cognitive functioning in aging adults over time: Comparisons with physical health, depression, and physical activity. Aging Ment. Health 21, 133 (2017).

Castellani, B., Griffiths, F., Rajaram, R. & Gunn, J. Exploring comorbid depression and physical health trajectories: A case-based computational modelling approach. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 24, 1293 (2018).

Cui, A. et al. Global and regional prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in population-based studies from 2000 to 2022: A pooled analysis of 7.9 million participants. Front. Nutr. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2023.1070808 (2023).

Ahn, J.-D. & Kang, H. Physical fitness and serum vitamin D and cognition in elderly Koreans. J. Sports Sci. Med. 14, 740–746 (2015).

Azzam, E., Elsabbagh, N., Elgayar, N. & Younan, D. Relation between vitamin D and geriatric syndrome. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 35, 123–127 (2020).

Nerhus, M. et al. Low vitamin D is associated with negative and depressive symptoms in psychotic disorders. Schizophr. Res. 178, 44–49 (2016).

Barbonetti, A. et al. Lower vitamin D levels are associated with depression in people with chronic spinal cord injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 98, 940 (2017).

de Koning, E. J. et al. Vitamin D supplementation for the prevention of depression and poor physical function in older persons: The D-Vitaal study, a randomized clinical trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 110, 1119–1130 (2019).

Lima-Costa, M. F., Andrade, F. B. & de Oliveira, C. Brazilian longitudinal study of aging (ELSI-Brazil). In Encyclopedia of Gerontology and Population Aging (eds Danan, Gu. & Dupre, Matthew E.) (Springer, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-69892-2_332-1.

Fiocruz. ELSI Brasil. http://elsi.cpqrr.fiocruz.br/ (2020).

de Andrade, F. B. et al. Inequalities in basic activities of daily living among older adults. Rev. Saude Publica 52, 14s (2019).

Giacomin, K. C., Duarte, Y. A. O., Camarano, A. A., Nunes, D. P. & Fernandes, D. Care and functional disabilities in daily activities—ELSI-Brazil. Rev. Saude Publica 52, 9s (2019).

Thacher, T. D. & Clarke, B. L. Vitamin D Insufficiency. Mayo Clin. Proc. 86, 50–60 (2011).

Ferreira, C. E. S. et al. Consensus—Reference ranges of vitamin D [25(OH)D] from the Brazilian medical societies. Brazilian Society of Clinical Pathology/Laboratory Medicine (SBPC/ML) and Brazilian Society of Endocrinology and Metabolism (SBEM). J. Bras. Patol. Med. Lab. https://doi.org/10.5935/1676-2444.20170060 (2017).

Radloff, L. S. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1, 385–401 (1977).

Demakakos, P., Zaninotto, P. & Nouwen, A. Is the association between depressive symptoms and glucose metabolism bidirectional? Evidence from the English longitudinal study of ageing. Psychosom. Med. 76, 555–561 (2014).

de Almeida, M. G. N., Nascimento-Souza, M. A., Lima-Costa, M. F. & Peixoto, S. V. Lifestyle factors and multimorbidity among older adults (ELSI-Brazil). Eur. J Ageing 17, 521–529 (2020).

Mazo, G. Z. & Benedetti, T. R. B. Adaptação do questionário internacional de atividade física para idosos. Revista Brasileira de Cineantropometria & Desempenho Humano 12, 480–484 (2010).

Matsudo, S. et al. Questinário internacional de atividade f1sica (IPAQ): estudo de validade e reprodutibilidade no Brasil. Rev. Bras. Ativ. Fís. Saúde 6, 5–18 (2001).

Ruan, Q. et al. Demographically corrected normative Z scores on the neuropsychological test battery in cognitively normal older Chinese adults. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 49, 375–383 (2020).

Rafiq, R. et al. Associations of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations with quality of life and self-rated health in an older population. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 99, 3136–3143 (2014).

Yang, A. et al. The effect of vitamin D on sarcopenia depends on the level of physical activity in older adults. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 11, 678–689 (2020).

Brito, T. A., Fernandes, M. H., da Coqueiro, R. S., de Jesus, C. S. & Freitas, R. Capacidade funcional e fatores associados em idosos longevos residentes em comunidade: estudo populacional no Nordeste do Brasil. Fisioter. Pesq. 21, 308–313 (2014).

de Souza, J. C. P., Cavalcante, D. R. C. & de Figueiredo, S. C. G. A Saúde Mental Do Amazônida Em Discussão. A saúde mental do amazônida em discussão (Editora Poisson, 2020).

Matos, F. S. et al. Redução da capacidade funcional de idosos residentes em comunidade: Estudo longitudinal. Cien Saude Colet 23, 3393–3401 (2018).

Silva, B. B. M. et al. Concentração sérica de vitamina D e características sociodemográficas de uma população idosa do nordeste brasileiro. Res. Soc. Dev. 10, e5910212268 (2021).

Barbonetti, A. et al. Lower vitamin D levels are associated with depression in people with chronic spinal cord injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 98, 940–946 (2017).

Gianfredi, V. et al. Depression and objectively measured physical activity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 3738 (2020).

Ramos, F. P. et al. Fatores associados à depressão em idoso. Revista Eletrônica Acervo Saúde https://doi.org/10.25248/reas.e239.2019 (2019).

da Oliveira, A. S. & Teixeira-Arroyo, C. Efeito do exercício na funcionalidade, na depressão e na dor de idosos institucionalizados. Geriatr. Gerontol. Aging 6, 48–55 (2012).

Kratz, D. B., Silva, G. S. & Tenfen, A. Deficiency of vitamin D (250H) and its impact on the quality of life: A literature review. Revista Brasileira de Análises Clínicas https://doi.org/10.21877/2448-3877.201800686 (2018).

de Souza, A. Q., Pegorari, M. S., Nascimento, J. S., de Oliveira, P. B. & dos Tavares, D. M. S. Incidência e fatores preditivos de quedas em idosos na comunidade: um estudo longitudinal. Cien Saude Colet 24, 3507–3516 (2019).

dos da Silva, P. A. S. et al. Prevalência de transtornos mentais comuns e fatores associados entre idosos de um município do Brasil. Cien Saude Colet 23, 639–646 (2018).

Campos de Oliveira, B. et al. Avaliação da qualidade de vida em idosos da comunidade. Revista Brasileira em Promoção da Saúde 30, 1–10 (2017).

de Coutinho, A. T. Q., Vilela, M. B. R., de Lima, M. L. L. T. & de Silva, V. L. Social communication and functional independence of the elderly in a community assisted by the family health strategy. Revista CEFAC 20, 363–373 (2018).

Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Elderly population increases 18% in 5 years and surpasses 30 million in 2017 https://agenciadenoticias.ibge.gov.br/agencia-noticias/2012-agencia-de-noticias/noticias/20980-numero-de-idosos-cresce-18-em-5-anos-e-ultrapassa-30-milhoes-em-2017 (2018).

Alves, J. E. D. As mulheres e o envelhecimento populacional no Brasil. Laboratório de Demografia e Estudos Populacionais (2016).

Acknowledgements

The Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) supports IJCS (Grant Number 307848/2021-3). The Foundation for Research Support of Santa Catarina (FAPESC) supports AMMS. The Coordination of Superior Level Staff Improvement (CAPES) supports VPC.

Funding

ELSI-Brazil was supported by the Brazilian Ministry of Health (DECIT/SCTIE—Grants: 404965/2012-1 and TED 28/2017; COSAPI/DAPES/SAS—Grants: 20836, 22566, 23700, 25560, 25552, and 27510).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.J.C.S. and A.M.M.S. developed the study hypothesis and study design. I.J.C.S. did the statistical analysis. I.J.C.S. and C.O. had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors contributed to study concept and design, analysis, and interpretation of data, and drafting or critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content or, in addition, data acquisition. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

dos Santos, A.M.M., Corrêa, V.P., de Avelar, N.C.P. et al. Association between vitamin D insufficiency and depressive symptoms, and functional disability in community-dwelling Brazilian older adults: results from ELSI-Brazil study. Sci Rep 14, 13909 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-62418-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-62418-z

- Springer Nature Limited